Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Energy in Southern Africa

On-line version ISSN 2413-3051Print version ISSN 1021-447X

J. energy South. Afr. vol.32 n.2 Cape Town May. 2021

https://doi.org/10.17159/2413-3051/2021/v32i2a5856

ARTICLES

The South African informal sector's socio-economic exclusion from basic service provisions: A critique of Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality's approach to the informal sector

B. Masuku; O. Nzewi

Department of Development Studies, University of Fort Hare, Alice, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This study explores the exclusion of informal micro-enterprises from the provision of basic urban infrastructure services in Duncan Village in East London, South Africa. It focuses on the informal food sector, which is dominated by women who are often held back from participating in economic activities that are more productive, as well as from social and political functions. Basic urban infrastructures, such as trading shelters with water and electricity connections provided by municipalities, are often expensive and most informal street traders find it difficult to access them. This study examines the energy struggles of the informal street food sector and its engagement with local government on issues ofinclusivity on policies regulating the sector. In-depth, semi-structured interviews and focus groups were conducted with 40 participants in the informal street food sector in Duncan Village. The findings reveal the lack of energy transition in the informal street food sector, because of its heavy reliance on low-quality fuels. Unreliable and expensive energy services force informal street food enterprises into using a limited range of energy sources. The findings also reveal that the relationship between the municipality and the informal street traders is one of exclusion and negligence. It is therefore suggested that government needs to recognise and value the informal sector and livelihoods of those involved in this sector, to take into account their needs, and engage with them when designing and implementing policies that regulate the sector.

Keywords: Energy needs; basic urban infrastructure services; informal sector; informal food sector; street traders; exclusion; service provision; women; energy services; local government; livelihoods

1. Introduction and study objectives

The informal sector is a major part of the global economy. Globally, about two billion people make their living from the informal economy and over 85% of people in Africa are employed within it. Furthermore, the informal sector contributes about 55% of Sub-Saharan Africa's gross domestic product (ILO, 2017; Ruzek, 2015:2). In South Africa, the informal sector has a smaller, but still significant, total share of employment, with over 2.5 million people, making up 20% of total employment in the country. It contributes about 5.1% of the country's GDP (StatsSA, 2019, Rogan & Skinner, 2017:9). The informal sector has always been considered as a temporary shelter for the poor (Mahlokoana et al., 2019). In South Africa, the formal economy is not inclusive of all; instead, it has huge disparities of inequality, and excludes the majority of the black population who are affected by high levels of poverty and unemployment (Ndulo, 2013). This has pushed most poor people into marginal conditions and forced them to forge survivalist strategies, which include joining the informal sector as traders (Skinner, 2016; Hamadziripi, 2009). This sector has proved to be everywhere persistent and permanent, and continues to grow around the world.

About three billion people across the globe are affected by energy poverty, defined by the International Energy Agency (2014) as 'lack of access to electricity and reliance on traditional biomass fuels for cooking'. They rely on traditional energy sources such as wood, biomass and dung for cooking and heating, and this affects health, education and gender equality. In Sub-Saharan Africa, more than 600 million people have no access to electricity (ILO 2018, IEA, 2014). For many economies in Sub-Sahara Africa, the informal economy has emerged as a significant socio-economic entity that provides a means of family subsistence income and sustainable employment (Chen, 2012). The informal sector1is one of the mechanisms used by the poor in developing countries to create income-generating opportunities (De Groota, et al., 2017; Skinner & Haysom, 2016). Furthermore, scholars like Rogerson (2016) and Skinner (2019) posit that the informal sector has become a major engine for employment, entrepreneurship and economic growth, especially in developing economies. The provision of basic urban services like energy remains a huge challenge in sub-Saharan Africa (Bailis 2015; Mtero, 2007). Over the past decades there has been a lack of focus and prioritisation of energy and energy access in international development agencies and national political decision-makers in Sub-Saharan Africa (Bailis, 2015). This is despite energy sufficiency and security being an essential prerequisite for sustainable development and a key to the provision of socio-economic development at regional, national and sub-national levels (Amigun et al., 2011).

The research study that this paper reports on emphasises the need to explore development alternatives that will lead to greater inclusivity of economic development and economic growth, and it suggests that one way to do that is to invest more in the informal sector, which has often been overlooked in economic policy analyses. The study focuses on the survivalist micro informal enterprises2that are heavily dominated by women traders who are self-employed and sometimes have to rely on a handful of employees, hired without social protection, most of whom do not pay any form of tax to the local authorities, lack union membership or written contracts, and do not have a fixed monthly income. It demonstrates the crucial role which basic municipal service provision, such as the Free Basic Alternative Energy policy (FBAE), plays in the informal food sector in ensuring access to food for the urban poor.

To understand the struggles of exclusion from the provision of basic urban infrastructure faced by informal street traders, this research used Duncan Village as a case study. Duncan Village is a black township in the Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality (BCMM) in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It was established in 1941 and named after the then Governor-General of South Africa, Patrick Duncan, who oversaw the opening of what was called a 'leasehold tenure area' on the East Bank of East London (The Mdantsane Way, March 2013). The township is about five kilometres from the East London city business district, and it is estimated that it has between 80 000 and 100 000 residents (Maliti, 2020). This location was chosen for this research study primarily because, firstly, Duncan Village has a long history of poor service delivery, struggles of poverty and socio-economic inequalities which have sparked violent protests particularly about poor service delivery of electricity and housing (Ndlovu, 2015); and, secondly, it is a township containing a wide range of small informal businesses (Ndlovu, 2015). It has a high unemployment rate, exceeding 50%, especially among the youth, and most people there depend on odd jobs and government social grants for survival (Ndlovu, 2015;). The history and the background of Duncan Village is crucial for understanding livelihoods and struggles of its ordinary people, who make a living through their engagement in informal sector businesses. Furthermore, the study endeavors to reflect the historical and present realities of South African black townships.

This study focuses particularly on the busiest areas, mainly the Esigingqini taxi rank. As a result of the large number of commuters, this taxi rank has attracted a number of informal traders, notably informal street food operators selling prepared and cooked food including pap (porridge) and chicken stew, beef stew, barbequed meat, amagwinya (vetkoek), boerewors (sausage) rolls, kota (bunny chow), inhloko (cow heads), amasondo (cow heels), amongst many others. The taxi rank was serves well as a case study because of its lucrative and increasing market opportunities and customer base for informal street trading.

The study finds that struggles faced by the people of Duncan Village, informal business operators included, have been understood as a struggle to meeting basic needs - such as having access to Free Basic Alternative Energy services (FBAE), which is part of the fulfillment of the promises of democracy in relation to socio-economic rights. The provision and accessibility of energy service are often determined by three factors: (i) a connection to the grid or (ii) an alternative off-grid solar system; and (iii) the affordability of that energy service. Poor households who are engaged in an informal sector business are often faced with challenges of energy poverty due being unable to afford clean energy, although the government has made an effort to implement poverty energy subsidies, such as FBAE, to support indigent households by providing them with fuels such as paraffin, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), and, in some areas, a solar power system. However, to date, only a very small number of households receiving FBAE, and this mostly in rural areas, while urban informal settlements remain largely excluded from this programme.

The study shows that 17% of the respondents in the informal food sector in Duncan Village relied on traditional energy sources, such as wood and charcoal, to cook their meals for selling, while 83% relied on a mix, using electricity and LPGs simultaneously. Those who relied on the coal and wood were faced with some difficulties in storing and preserving perishable products such as meat, fish, polony, cheese, fresh milk and soft drinks, as this requires refrigeration. Lack of electricity deprived them of cooling storage facilities, which led to spoilage and increased chances of food poisoning, loss of customers and low incomes to sustain livelihoods (Matinga et al. 2015). Most of the participants indicated that they relied on their neighbours and friends who had access to electricity to store their perishable products.

Lack of access to modern and efficient energy sources impacts negatively on the user's health, respiratory diseases can be induced from using wood and charcoal (Matinga, 2010; IEA, 2010). This study is, however, cognizant of the fact that informal food enterprises sometimes use traditional sources of energy such as wood and charcoal, not because they do not have access to electricity, but because of the type of product they are preparing.

To critique BCMM's approach to the informal sector, this paper used the FBAE framework. The FBAE was promulgated in 2007 by the Department of Energy. Its main objective was to provide alternative energy services - LPG, bio-ethanol gel-fuel, paraffin, solar home systems and coal (DME, 2007) - to households not connected to the national electricity grid, to address the socio-economic issues that arise from inadequate provision of energy to households. The study is fully aware that the FBAE policy objectives are aimed at providing alternative energy sources to indigent households not connected to the grid and not specifically to the informal sector business. However, this article uses the FBAE strategy to demonstrate how the BCMM at local government level together with the aid of provincial and national government structures could invest more in alternative energy sources, such as renewable energy, that could be directed towards assisting the informal sector enterprises that struggle with energy access in conducting their business. It was chosen as the most suitable framework approach which could be used by the government to support the informal sector and bridge the energy gap it faces, particularly the street food sector which heavily relies on energy. This study focuses on the lives of informal traders, their struggles, their fears and their hopes.

The study shows that only 14% of participants running informal food business in Duncan Village are benefiting from municipal services such as Free Basic Electricity (FBE) at a household level. It should be taken into account that municipal free basic energy services such as FBE are not provided for business purposes, but to indigent households for basic energy use. Those running spaza business within their homes are using the FBE service for business activities such as cooking fast foods (fish, chips, sausages, kota, magwinya, etc), for cooling soft drinks, and for lighting, among others. However, the general concern raised by households receiving FBE is that it is inadequate to cover both households and business energy needs; as a result this has forced them to resort to alternative sources of energy, such as generators and illegal power connections. The study shows that none of the participants at this stage is benefiting from either the FBE or FBAE services in their households.

This study argues that modern energy sources, such as electricity and renewable energy, play an important role in providing sustainable energy to increase supply security through diversification (energy mix), which is much needed by the informal sector. The conclusion drawn, based on these findings, is that alternative energy is even more vital than electricity for small businesses such as the informal food sector. This means the government needs to invest more in alternative energies and support the informal sector with clean energy which is convenient and affordable to low-income households. For this reason, there is a huge need for government to strengthen and diversify the FBAE framework for a sustainable energy3 development path that is socio-economically viable for the informal sector.

1.1 The informal sector problem Government policies and plans, not only in South Africa, but across Sub-Saharan Africa, still view the informal economy as a welfare problem (Stephan et al., 2015). This perspective, neglecting the informal economy and millions of people living therein, has led to a significantly underdeveloped informal sector across the continent (Shabalala, 2014). The repercussions of this approach are that governments face a huge social problem which cannot be solved by social grants alone. In South Africa, local government strategies, such as the Local Economic Development framework, meant to support local businesses and stimulate economic growth, do not directly support the survivalist informal traders, especially the informal street traders selling cooked food in public open spaces and from temporary or mobile shelters within and outside urban areas. Moreover, there is no energy transition in the informal street food sector, because of its heavy reliance on low quality energy sources like wood and charcoal in the face of a lack of an affordable and reliable energy supply. In addition to this, the informal street food sector is dominated by women who are often excluded from equal access to education and employment as well as to ownership and control over resources, due to the patriarchal structure of the society. Local government often sees informal street traders as law-breakers dealing in illicit goods, who need to be stopped and controlled through harsh methods such as confiscation of goods or paying hefty fines (Skinner 2016; Rog-erson 2004). The basic urban infrastructures, such as trading shelters installed with water and electricity connections provided by municipalities, are often expensive and most informal street traders find it difficult to access such facilities as they are unable to afford them.

1.2 Study objectives

The main objective of this article is to critically analyse the role of BCMM in the informal economy, particularly in the provision of basic energy services to the informal sector. Within this objective, the study aims to:

• find out the extent to which local government interpretation of the FBAE, as implemented

through municipal indigent policies, addresses local economic development, notably the support of informal businesses;

• investigate the extent to which the informal food sector contributes to the socio-economic improvement of livelihoods of the poor;

• make recommendations on how the findings can address challenges in this area.

1.3 Significance of the study

Previous studies indicate that, despite the importance of energy in the informal food sector, little is known about the dynamics of energy use by informal food enterprises (Groot et al., 2017). This paper has used the following literature as its yardstick for its arguments: Mahlokoana et al. (2019); Matinga (2015); Matinga and Annegarn (2013); Skinner (2008; 2016). These studies speak to the informal food sector using energy in order to survive, but are silent about the role of local governance in driving and formulating policies and strategies that favour the growth and development of the informal business sector, especially the informal food enterprises that rely on different energy sources.

The current research study is significant in that it endeavours to bridge the relationship gap between local government and the informal sector, particularly the survivalist informal traders who have no safety nets and are often excluded from any form of government assistance directed at small businesses. It argues that the choice of type of energy used is determined by several factors which include, but are not limited to, the type of product sold, geographic location, customer taste preferences and the spatial planning rules within a city. The study aims to assist in policy formulation and debates that advocate for the informal sector business, and also to regard the FBAE as a strategy which can be used to provide a wide variety of energy sources as safety nets for the informal food sector.

2. Literature review and methodology

2.1 Literature review

The study used the statist approach4 as its framework to argue the role of the state in service delivery, in order to understand the struggles faced by informal businesses on issues surrounding the access and provision of energy in South Africa. The adopted theoretical frameworks provide a basis for understanding and analysing the livelihoods of urban informal workers involved in the informal food sector activities in Duncan Village. This approach was chosen to demonstrate the pivotal role played by the state in acting as custodian of legal and regulatory frameworks to govern the informal economy (Mkandawire, 2001). A welfare state is understood as a state whose interference in the economy is to protect and promote the material well-being of individuals, against the operation of market forces (Monyai, 2011). The statist approach was used to argue the role of local government, particularly with regard to municipal by-laws, in regulating and controlling informal trade, with the aim of promoting local economic development. The statist framework has been useful in coming to understand how structures and institutions, such as local government support programmes and by-laws, affect informal businesses. Existing literature on informal trade indicates that there is a lack of support offered by government structures in assisting survivalist informal businesses in South Africa (Pavlovic, 2016; Tshuma and Jari, 2013; Sello, 2012).

3. Research methodology

This study used a qualitative research approach to collect the relevant data. This enabled the researchers to describe, interpret and better understand the challenges of exclusion faced by informal business -in particular, survivalist informal street food operators. Data was gathered through a combination of in-depth and semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions. The use of interviews also enabled the researchers to probe, observe, and explore the answers given by respondents, as well as to allow them to narrate their struggles concerning energy access. The study also used secondary documents such as policy documents, books, journals, newspapers and articles. Policy documents in relation to municipal regulations affecting the informal sector were requested from the BCMM archives. The researchers were obliged to abide by the ethical standards of the University of Fort Hare. The researchers adhered to ethical procedures of the BCMM and gained permission to conduct a study within Duncan Village. The researchers obtained written consent from respondents to take part in the research.

3.1 Population and study sample

The population5 in the context of this study were informal street food traders operating in the Esigxingini taxi rank in Duncan Village. The study applied a purposive sampling method to collect data. This enabled researchers to identify relevant and key participants - the informal food operators indicated above. A snowball sampling technique6was also adopted. This study focused on a sample of 40 participants comprised of seven groups. The researchers considered this sample size adequate for a qualitative study to make and appropriate analysis of the collected data. Six groups each had six members from informal street food enterprises in the following groups: those run by local citizens (South African citizens); those run by foreign nationals; those using municipal trading sites and infrastructure; those conducting business in public open spaces; those operated by women; and those run by men. The seventh group comprised four participants from BCMM: two municipal administrators, and two ward councilors from Duncan Village who work closely with the informal sector businesses. The study would have liked to interview a representative from an association of informal trader businesses in Duncan Village, but there was no such functional association. The selected participants were considered to be helpful to ascertain if the claim, made by some researchers, that government turns a blind to the informal sector are true or not, considering that municipalities play a crucial role in service. The BCMM administrators were selected through referrals and identification by the relevant office i.e. the office of the municipal manager, while ward councilors were accessed through door-to-door visits to relevant offices where they conduct their daily operations.

3.2 Field work experiences and challenges faced

Prior to undertaking the interviews, the researchers gathered relevant information on the study topic by utilising previous literature relevant to the topic. It was crucial for researchers to have a better understanding of the study by knowing the background information so as to contextualize and develop an interview schedule (see Annexure A in the supplementary material) that guided the interviews. A consent form for all participants (see An-nexure B) was also developed. Participants were informed that their participation in the study was voluntary and that they had a right to privacy, confidentiality and anonymity. Respondents were also fully aware that they would be no personal benefit to them from participating; and they were at liberty to withdraw from the study at any time if ever they felt uncomfortable.

During the field work of data collection, some significant general observations were made. Firstly, gender dynamics were evident throughout the data collection. Females were dominant in the informal sector businesses as compared to their male counterparts. Secondly, it was noted that most of the people in Duncan Village, in particular households and those running both formal and informal business are now research-fatigued, as many students conducting research had visited the area (although none of these studies had investigated the impact of FBAE in the survival of informal sector businesses). The researchers also noted that a number of local informal business operators - in particular, unregistered ones - were hesitant to be interviewed, mainly through lack of trust and fear of harassment by the authorities.

Despite following all the ethical measures undertaken, some challenges were encountered in the research. The researchers faced some difficulty in setting up appointments with BCM officials. Among those identified from the senior executive office, only the senior clerk from the department of local economic development could be interviewed. Efforts to interview the municipal manager were not successful, despite being identified as a main informant by the research office. Last but not least, some potential participants, particularly informal operators conducting their business from the streets were not willing to participate, as they thought the researchers were government agents. In order to minimize these concerns, the researchers had to explain to the respondents that the study was solely for academic purposes and that the information they provided with as well as their privacy would be protected and not be disclosed to anyone without their acknowledgement and permission

4. Study findings

This study adopted a thematic analysis, a descriptive presentation of data which is widely used in qualitative data (Tracy, 2013). Thematic analysis is a qualitative research approach based on participants' conceptions and perceptions, and focuses on examining themes within data (Babbie, 2010). This allowed for discussion of common themes and statements from the data collected. In qualitative data analysis, collected data is transformed into relevant and meaningful research findings (Tracy, 2013). The process of data analysis is an intensive process that requires careful planning and coordination of information to give comprehensive findings (Babbie, 2010). The findings of the study were presented using the demographical profile of the participants, through discussion of findings and graphical format by using themes and sub-themes. Literature was also used to support and validate the study findings and interpretations of results.

4.1 Energy struggles faced by informal businesses in Duncan Village

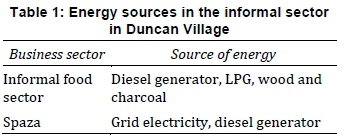

According to the 2012 study survey conducted by the Department of Eenergy, 47% of South Africans are energy-poor, and spend more than 10% of their income on energy services (DOE, 2012). Table 1 shows energy sources used by informal businesses in Duncan Village.

Informal business operators, in particular street food vendors, stated that they had no access to grid electricity, as they use temporary structures and operate in an open space with no electricity connection; so they heavily relied on LPG, generators, and sometimes coal and wood when they have no money to buy gas. Participants also indicated that

electricity usage limited them to do business else where where there is no grid connection. Thus, access to alternative energy sources, such as gas, provided them with mobility to cook and sell their fast food products in busy functions such as sports fields, show grounds, parks and roadsides.

The informal food operators indicated that their business has a wide range of clients, including office workers, travellers, schoolchildren and households. They also indicated that many local people preferred to eat their food rather than eating at restaurants because theirs was affordable. However, they also said that when food and cooking fuel costs increase they increase the price - e.g., a plate of pap and beef stew increased from R20 to R30.

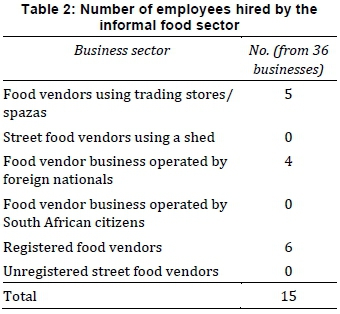

Table 2 shows that only 42% of informal food sector businesses in the study provide employment opportunities to the local community, the majority of them those food vendor business operated which are registered and which are owned by foreign nationals (Somalians). Thus, 58% of the participants were sole-trader businesses, run with the assistance of family members and were unable to hire additional staff due to the low income generated by the business.

Reasons for participating in informal business generally include pure survival mechanisms to cope with unemployment, and a desire for independence, flexibility of work arrangements and freedom of total control and ownership of business without government intervention and control (Chen, 2012). However, this study shows that the involvement of the majority low income households in the informal business sector in Duncan Village is solely a survival strategy, to earn a living. Despite that, 75% of the respondents demonstrated a positive initiative, in that they were willing to contribute positively to job creation if only the government could support them with the necessary resources and infrastructure to grow their business.

4.2 Constraints to growth of the informal business sector

The study findings below indicate the constraints faced by the informal business sector in Duncan Village. Paramount to the constraints raised by the participants was a lack of financial support services and a lack of access to basic urban infrastructure. These findings confirm what has been already discussed by other supporting literature used in this study (see above).

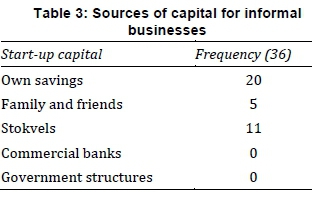

4.2.1. Access to financial support services

Participants indicated that they fund their business from their personal incomes. None of the respondents indicated getting funding from local government structures or any non-governmental organisation. Most of the participants indicated that they have no bank accounts for their businesses as their enterprises were not formally registered. Some respondents stated that sometimes they were forced to take out credit from an informal credit scheme commonly known as (stokvel) to buy stock and cushion their businesses. This indicates difficulties faced by informal businesses, in particular survivalist enterprises without access to financial support, and this constrains the operation of their business. The results are compatible with the literature review, which revealed that informal businesses struggle to get necessary support from government structures (Skinner, 2006). Table 3 shows the sources of start-up capital and finance for informal businesses in Duncan Village. It indicates that 56% of informal business relied on their own savings to start a business and sustain it, while 13% got some start-up capital from family and sometimes close friends, and 31% relied on stokvels. None of the small informal businesses in Duncan Village receive any financial assistance from commercial banks or government funding sectors. Most of the respondents expressed that they did not bother to approach banks for funding because of tough lending regulations imposed by banks. Since most of the informal businesses in Duncan Village are not licensed and operate outside government regulations, they do not have collateral to qualify for any form of bank or government funding. This means they must rely on family borrowings and stokvels where the interest rate charged is exorbitant and often keeps borrowers indebted.

4.2.2. Lack of access to basic urban infrastructure

The study also found that informal businesses in Duncan Village, especially those operating along roadsides and in open spaces, struggle to conduct business in harsh weather conditions (scotching sun, rain, wind and cold) due to lack of urban infrastructure. 83% indicated that they have no access to basic services such as clean water, electricity or clean energy sources to conduct business. None of the respondents indicated that they used designated municipal trading stalls. Respondents expressed their worries that the areas in which they operate their businesses are not safe and the environment is not conducive to run a business. This is consistent with the G12 study of Small Towns Business Development Initiative (2011) which found that infrastructure and services are amongst the biggest constraints affecting the informal sector.

4.3 Engagement between the local government and the informal sector

Findings in this section are drawn from informal business owners and BCMM administrator participants, and thus show different perspectives. There is dissatisfaction from the informal business owners with regards to their neglect by the municipality from inclusive economic development, while, on the other hand, the BCMM administrators claim to be playing a positive role in promoting local economic development and providing necessary support to small businesses.

4.3.1 Views from the informal sector

The findings show that the BCMM does not recognise survivalist enterprises as businesses that can be supported by any of the local government structures, due to their lack of registration, as these businesses operate outside the local government regulation structures. These findings are consistent with studies by Chen (2012) and Skinner (2016) who argue that many informal businesses believe that they are excluded from accessing basic urban infrastructure and from integrated development processes on decision-making affecting them, and as a result this makes informal businesses vulnerable to negative forces, such as exploitation by local government officials.

Participants were asked if they get any form of support in their business from any government structures or whether their businesses had been affected by any state regulations. Notably, all 36 participants within the informal sector indicated that they have never had any form of assistance from the municipality or local government structures. Moreover, they were asked about any state enforcement affecting their businesses and stated that they were very aware of law enforcement, as they often encountered metro police, municipal agents and in specting officers from the Department of Health and the Fire Department who, from time to time, would visit small businesses in Duncan Village to inspect whether the businesses were complying with local government regulations.

Most of the informal businesses interviewed in this study are unregistered and are run by people that joined the informal sector to earn a living. The participants indicated that they were very disappointed with how their local government treated informal businesses.The participants suggested that their relationship with the local government is hostile and stated that the government did not care about the struggles they face in accessing basic needs and the efforts they were making to improve their livelihoods by engaging in the informal business sector.

4.3.2 Views from BCM administrators

This section provides an overview of the interview sessions with BCMM administrators. The findings indicate that the municipality is far from reaching its intended objectives of providing infrastructural support service to small informal businesses in order to promote economic development. The administrators who were interviewed admit that there is no direct assistance from the municipality given to survivalist enterprises with regards to provision of infrastructure and supportive services such as finance, trading sites, or storage facilities. The BCM at this time only provides assistance and support to registered small business, in particular, SMMEs who are said to comply with municipal laws and regulations.

One of the objectives of the Integrated Development Plan of the BCMM is to provide electrification, via new extensions and FBE, as well as alternative renewable energies such as FBAE, in the form of paraffin for wards without electricity. Electricity supply remains a huge challenge in the BCMM, due to budget constraints and a shortage of skilled labour such as engineers. For instance, the electricity network in Buffalo City is currently in a poor condition, which has led to power outages and a poor-quality supply of electricity to consumers (BCMM IDP, 2017/18).

The BCMM administrators indicated that the municipality provides information sessions and training on business/entrepreneurship skills to local informal business operators in Duncan Village. The municipality also continuously encourages the informal business operators to comply with local municipal regulations and register their businesses with cooperatives. The BCM also reported that they were much concerned with the resistance of survivalist operators who did not want to register their business, as they could only work with those informal businesses that are cooperating and complying with the municipal regulations, while those who choose not to comply will be dealt with harshly and forced to comply. On the contrary, the literature cited above, as well as responses obtained from informal business operators in Duncan Village, revealed that the sector is not sufficiently informed about municipal support service structures that stand for the informal sector's needs.

As part of the LED strategy mechanism to promote local economic development, the BCMM embarked on the long-term project known as the Duncan Village Redevelopment Initiative. This project is funded by the Department of Local Government and Traditional Affairs. The project is aimed at promoting the local economy, with the intention of providing valuable services to the community of Duncan Village. The programme comprises five apex projects: building a sports complex, a brickyard, an agri-village, and environmental revitalization (BCMM IDP, 2017/18). Furthermore, the BCMM also indicated that, as part of the IDP, they have made a commitment to building a mini market for street traders in Duncan Village. The BCMM indicated that these projects are underway.

To summarize the themes which emerged from semi-structured interviews with BCMM administrators, this study asserts that little attention is given to survivalist informal businesses, who remain excluded from the BCM IDP, as priority is given to SMMEs. Although the BCMM indicated that they were making efforts to support unregistered informal businesses, evidence shows that the survivalist and small businesses remain neglected, due to their small size and failure to adhere to legal requirements

5. Conclusion and recommendations

The study findings reveal that there is no proper coordination or consultation between the municipality and the informal business operators; the relationship that exists between the two is that of exclusion and negligence. Therefore, there is a need for the BCMM to work closely with the informal business operators and to prioritise issues that promote growth and development. Local government structures need to work collectively and closely with other financial stakeholders, like banks, and to engage them to develop credit systems that will provide financial assistance to informal business operators who are in need of funding to conduct their business.

The study findings reveal that the informal business operators in Duncan Village rely on personal income, borrowings from friends and informal lending schemes (stokvels) to run their businesses. This often constrains the performance and productivity of their businesses - due to the lack of stability of their financial resources. Thus, this study recommends that the government finds ways to bring financial lending schemes, like banks, on board to enable low-income households without collateral to qualify for the bank loans which will boost their businesses and grow the informal business sector.

The study findings show that the BCMM does not see how the FBAE services can feed into economic development; instead, it views these frameworks as safety nets to assist the indigent with access to basic energy to alleviate poverty levels. This study recommends that such services should not be seen as safety nets that only address the social problems of poverty alleviation. The frameworks should also be used to promote the social welfare and economic wellbeing of low-income households. This can only be achieved when free basic services are extended to cover low income households who are engaged in the informal sector as informal business owners.

Notes

1 The informal sector is production and employment that takes place in unincorporated small or unregistered enterprises (Chen, 2012:8)

2 Survivalist micro enterprise, also referred to as 'necessity-driven', refers to the marginalised and poor workers, particularly women ,who are the chief operators in this informal sector and usually view their involvement in the informal economy as a temporary survival strategy (Rogerson, 2004; 2016). Survivalist businesses tend to be single-person firms conduct-ing-small scale activities which offer lower wages (Makoma, 2018; Makaluza, 2016)

3 Sustainability refers to something with durability that lasts over time. For energy to be sustainable, it must improve the health of ecological and socio-economic systems and their ability to adapt to change (Winkler 2006).

4 The statist approach promotes a developmental welfare system, which is based on people-centred development, social investments in human capabilities and the building of social capital (Mkandawire, 2001).

5 The study population refers to aggregation of elements from which the sample is derived (Babbie, 2010 cited by Wadi, 2015).

6 Snowballing is a technique often used in field research, where targeted participants to the study may be asked to suggest additional people fitting the same criteria for interviewing (Babbie 2010, cited by Wadi 2015).

Author contributions

B. Masuku conceptualised the study, collected and analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript. O. Nzewi supervised research and assisted with proofreading and editing.

References

Amigun, B., Musango, J.K. & Stafford, W., 2011. Biofuels and Sustainability in Africa. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 15: 1360-1372. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2010.10.015 [ Links ]

Bailis, R., 2015. Energy policy in developing countries. In Patz, J and Levy, B (Eds.) Climate change and public health. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press: 291-302. [ Links ]

Babbie, E., 2010. The practice of social research. 12th edn. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage. [ Links ]

Chen, M. A., 2012. The informal economy: Definitions, theories and policies. Women in informal economy globalizing and organizing (WIEGO) Working Paper 1, Cambridge, MA. [ Links ]

Chen, M. A., 2014. Informal Economy Monitoring Study Sector Report: Home-Based Workers, WIEGO, Cambridge, MA, available at http://wiego.org/sites/wiego.org/files/publications/files/IEMSHome-Based-Workers-Full-Re-port.pdf. [ Links ]

Hamadziripi, T., 2009. Survival in a collapsing economy: A case study of informal trading at a Zimbabwean flea market. A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology), University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Clancy, J.S., Skutsch, M.M. & Batchelor, S., 2002. The gender-energy-poverty nexus: Finding the energy to address gender concerns in development. Paper prepared for the UK Department for International Development (DFID), London [ Links ]

De Groot, J, Mohlakoana, N, Knox, A & Bressers, H., 2017. Fueling women's empowerment? An exploration of the linkages between gender, entrepreneurship and access to energy in the informal food sector. Energy Research & Social Science 28, 86-97. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2017.04.004 [ Links ]

Department of Minerals and Energy, 2003. Electricity basic services support tariff, Free Basic Electricity Policy. Pretoria [ Links ]

Department of Mineral Energy, 2007. Free Basic Alternative Energy Policy. (Households Energy Support Programme). Pretoria. [ Links ]

ILO, 2007. 298th Session of Governing Body Committee on Employment and Social Policy: the informal economy (GB.298/ESP/4). Geneva: International Labour Office. [ Links ]

ILO, 2017. International Labour Standards on Social security. [Online]. Available: http://www.ilo.org/global/stand-ards/subjects-covered-by-international-labourstandards/social- [ Links ]

International Labour Organization, 2018. Women and men in the informal economy: A statistical picture Copyright ©security/lang--en/index.htm [Accessed 22 May 2017]. [ Links ]

International Energy Agency, 2010. Energy technology roadmaps: a guide to development and implementation. Available online: http://www.energy.gov.za/files/SETRM/EnergyTechRoadmaps/Roadmap-guide.pdf [accessed 16 June 2017]. [ Links ]

International Energy Agency, 2014. Africa Energy Outlook. A focus on energy prospects in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Energy Outlook special report. International Energy Agency, Paris. [ Links ]

Israel-Akinbo, S., Snowball, J. & Fraser, G., 2017. The energy transition patterns of low-income households in South Africa: An evaluation of energy programme and policy. Paper presented at the economic society of South Africa biennial conference 2017, Rhodes University, Grahamstown [ Links ]

Makaluza, N., 2016. Job-seeker entry into the two-tiered informal sector in South Africa. REDI3x3Working paper 18, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Makoma, M., 2018. Women in the informal economy: Precarious labour in South Africa. Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts (Political Science) in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University [ Links ]

Matinga, M., 2010. "We grew up with it". An ethnographic study of the experiences, perceptions and responses to the health impacts of energy acquisition and use in rural South Africa. University of Twente, Netherlands. [ Links ]

Matinga, M. N., 2015. LPG and livelihoods: Women in food processing in Accra. ENERGIA newsletter 16 September 2015. 11-14 [ Links ]

Matinga, M.N. & Annegarn, H.J, 2013. Paradoxical impacts of electricity on life in a rural South African village. Energy policy 58, 295-302. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2013.03.016 [ Links ]

Malonza, R. & Fedha, M.L., 2015. An Assessment of Gender and Energy in Kenya. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research Volume 4, ISSN 2277-8616 137 [ Links ]

Mohlakoana, N., 2014. Implementing the South African Basic Alternative Energy Policy: A Dynamic Actor Interaction. Doctoral thesis, University of Twente, Enschede. [ Links ]

Mohlakoana, N., de Groot, J. Knox, A. & Bressers H., 2019. Determinants of energy use in the informal food sector, Department of Governance and Technology for Sustainability. University of Twente, Netherlands, 36:4,476-490, doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2018.1526059 [ Links ]

Monyai, P.B., 2011. Social policy and the state in South Africa: Pathways for human capability development. PhD thesis. Department of Development studies, University of Fort Hare. [ Links ]

Mkandawire, T., 2001. Social Policy in a development context. Social policy and development Programme Paper No.7: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, Geneva, Switzerland. [ Links ]

Mtero, F., 2007. The informal sector: micro-enterprise activities and livelihoods in Makana municipality, South Africa. Master's thesis. Industrial Sociology. Rhodes University [ Links ]

Mwasinga, B., 2013. Assessing the implications of local governance on street trading: A Case of Cape Town's inner city. Masters dissertation, School of Architecture, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Nackerdien, F. & Yu, D., 2017. A panel data analysis on the formal-informal sector linkages in South Africa. Paper presented at the economic society of South Africa biennial conference 2017, Rhodes University, Grahamstown. [ Links ]

Ndlovu, P., 2015. Understanding the local state, service delivery and protests in post-apartheid South Africa: The case of Duncan Village and Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality, East London. Master's dissertation. Industrial Sociology, University of Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Ndulo, M., 2013. Failed and failing states: the challenges to African reconstruction. Cambridge scholars, Newcastle, UK. [ Links ]

Pavlovic, I., 2016. What are the factors that contribute to the exclusion of the iSMEs, particularly informal Micro Enterprises (iME), from the SMEs policies in Rwanda and Senegal? University of Twente, Netherlands. [ Links ]

Rogan, M. & Skinner, C., 2017. The nature of the South African informal sector as reflected in the quarterly labour-force survey, 2008-2014. REDI3x3 Working paper 28, University of cape Town. [ Links ]

Rogerson, C., 2008. Tracking SMME development in South Africa: Issues of finance, training and the regulatory environment. Urban Forum, 19(1): 61-81 [ Links ]

Rogerson, C., 2016. South Africa's Informal Economy: Reframing Debates in National Policy Local Economy 31: 172-186. [ Links ]

Ruzek, W., 2015.The informal economy as a catalyst for sustainability. Department of geography, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306, 2015, 7, 23-34. [ Links ]

Sello, K., 2012. Former street traders tell their stories (Narratives in the inner city of Johannesburg. Bachelor of Science (Honours) in Urban and Regional Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Shabalala, S., 2014. Constraints to Secure Livelihoods in the Informal Sector: the Case of Informal Enterprises in Delft South, Cape Town. Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of City and Regional Planning in the School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics. University of Cape Town [ Links ]

Skinner, C., 2006. Falling through the Policy Gaps? Evidence from the Informal Economy in Durban, South Africa. Urban Forum. 17(2), 125-148. [ Links ]

Skinner, C., 2008. Struggle for the Streets: The Process of Exclusion and Inclusion of Street Trader in Durban, South Africa. Development Southern Africa 25, 2: 227-242. [ Links ]

Skinner, C. & Haysom, G., 2016. The informal sector's role in food security: A missing link in policy debates? Working paper No. 44, PLAAS, UWC and center of excellence on food security, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Skinner, C., 2016. The Nature, Contribution and Policy Environment for Informal Food Retailers: A Review of Evidence. Annotated Bibliography for the Consuming Urban Poverty Project, African Centre for Cities, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Skinner, C., 2019. Informal-sector policy and legislation in South Africa: Repression, omission and ambiguity. University of Cape Town [ Links ]

StatsSA, 2019. Quarterly Labour Force Survey - Quarter 3, 2019. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria [ Links ]

Stephan, U., Hart, M. and Drews, C. 2015. Understanding motivations for entrepreneurship a review of recent research evidence. Enterprise Research Centre and Aston Business School, Aston University, Birmingham, pp. 1 - 54. [ Links ]

Tshuma, M.C. & Jari, B., 2013. The informal sector as a source of household income: The case of Alice town in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. Journal of African Studies and Development 5(8), 250-60. [ Links ]

Tracy, S.J., 2013. Qualitative Research Methods. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell [ Links ]

Wadi, C., 2015. Livelihood Strategies of Female-headed Households in the coloured community of Sunningdale in Harare, Zimbabwe A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Social Sciences. Rhodes University [ Links ]

* Corresponding author: Tel.: +27 (0)78 1 93 0874; email: masukublessinqs@gmail.com