Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Wits Journal of Clinical Medicine

On-line version ISSN 2618-0197Print version ISSN 2618-0189

WJCM vol.7 n.1 Johannesburg Feb. 2025

https://doi.org/10.18772/26180197.2025.v7n1a5

OPINION PIECE

Good health and well-being in South Africa for a sustainable future

Brian Chicksen

Advisor to the Executive: Special Projects, Executive Office, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Achieving good health and well-being for all South Africans is a significant national issue. In the broader context, good health and well-being are also global issues, and as such, they are the primary focus of one of the United Nations' 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) - SDG 3. It represents a complex challenge that interfaces with the other 16 SDGs and cuts across all dimensions of sustainable development: politico-legal and governance, social, economic, and environmental. In responding to the complex challenge, certain paradigm shifts are needed, including moving from transactional to transformational approaches where all stakeholders are part of solutions for the collective good. This entails building trust across stakeholder groups for effective collaboration and generating and applying innovative and creative solutions. A preliminary pathway to impact is proposed to advance the conversation.

Keywords: Sustainable development goals, sustainable development, collaboration, health systems, transformational change.

INTRODUCTION

It is well recognised that good health and well-being are integral to sustainable development. To this end, it is the primary focus of one of the United Nations (UN) 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) - SDG 3. These goals represent the world's collective commitment towards creating a sustainable future for all and are detailed in the declaration "Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development".(1) The goal seeks to ensure healthy lives and the promotion of well-being for all at all ages.(1)

While it is described discretely as a goal, it is evident that it shares two-way relationships with the other goals: on the one hand, attaining SDG 3 aspirations is contingent on progress in different goals and on the other, achieving progress towards SDG 3 targets is a significant contributor towards attaining other goals. Indeed, good health and well-being are a prerequisite to a just and inclusive societal development.

The interconnected nature between good health and well-being and other dimensions of sustainable development highlights the complexity, where pursuing health for a meaningful existence may be regarded as a "wicked problem".(2) This is undoubtedly the case in the South African landscape, where causes of poor health are multi-faceted, relationships between different constituencies are fractious at best, and the consequences of poor health are far-reaching.

In advancing the conversation, this paper seeks to clarify some of the complexities at hand, present a conceptual and philosophical approach to navigating them, and proposes a potential pathway toward strengthening health systems to improve the health of the population.

SDG 3 WITHIN THE SDG FRAMEWORK - FIRST-ORDER COMPLEXITY

While the SDGs represent a significant step in aligning the aspirations of the UN member nations and a compelling rallying call to take sustainable development seriously, they have certain limitations. In this sense, they tend to present a linear perspective in that interrelationships between and across SDGs are not fully articulated. Notwithstanding any limitations, internalising and making sense of the SDGs in our context helps to establish a shared understanding of them and mobilise focused efforts towards their accelerated achievement.

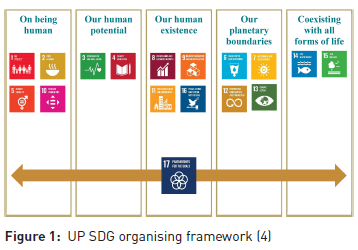

There are many ways to contextualise the SDGs. The University of Pretoria views them as being centred on the human condition in the broadest terms and the state of humanity and human existence in relation to a changing world.(3) Using this perspective, the university has developed an organising framework for the SDGs shown in Figure 1.(4) It begins to surface their linkages and dependencies, albeit still in a somewhat linear form.

At the outset, we consider our basic humanity - being human. We seek to address fundamental aspects of the human condition, considering the many faces of poverty and inequality (SDGs 1,5 and 10) and the absence of hunger (SDG 2). As we fulfil these fundamental conditions, we set ourselves up to reach our full potential. This potential is realised through good health and well-being (SDG 3) and quality education (SDG 4). The extent to which we reach our potential shapes the way we improve the human condition through decent work and economic growth (SDG 8), the industries and infrastructure that we create (SDG 9), the safe cities and communities that we develop (SDG 11), and our ability to co-exist peacefully and supported by capable institutions (SDG 16). As we enhance the human condition, we must be mindful of our planetary boundaries reflected in the resources we use (SDG 6 and SDG 7), our production and consumption patterns (SDG 12), and our impacts on climate (SDG 13). We must also embrace co-existing with all life forms - under water and on land (SDG 14 and SDG 15). SDG 17 focuses on partnership and collaboration to amplify impact, and cuts across the other 16 SDGS.

Within this organising framework good health, well-being, and quality education serve as critical levers driving human-centred sustainable development. In their absence, we cannot have a meaningful existence or achieve sustainable development where nobody is left behind.

GOOD HEALTH AND WELL-BEING IN THE BROADER CONTEXT OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT -SECOND-ORDER COMPLEXITY

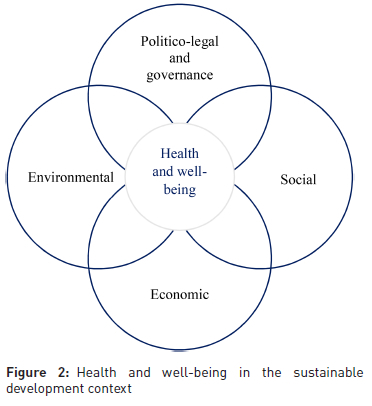

Considering health and well-being in relation to the broader and interlinked dimensions of sustainable development (political, legal, governance, social, environmental, and economic) brings more clarity to the complexity faced. Health has multifaceted interfaces across these dimensions in various two-way relationships, as shown in Figure 2.

Extending the One Health (5) concept articulated by the World Health Organisation (WHO), health and well-being not only interfaces with, and requires an integrated approach across social and environmental ecosystems, it also crosses politico-legal and economic ecosystems.

These interfaces were brought sharply into focus during the COVID-19 pandemic. Evolving from environmental sources, COVID-19 viral infection spread rapidly across the globe, and the infection along with the controls imposed to curb its spread had profound social impacts at individual and societal levels. Economic impacts were devastating, with widespread business closure and delayed economic recovery after the pandemic was resolved. Throughout the pandemic, political influences were highlighted by vaccine nationalism and amplified divisions between the global north and south.

Similarly, for health systems within South Africa, with the country's high levels of poverty, inequality, and disease burdens, ensuring broadened access to good quality health care are concurrently political, social, and economic issues.

In the face of such complexity, traditional linear approaches to good health and the well-being of the entire populace are no longer valid.

A NEW CONCEPTUAL APPROACH TO NAVIGATING COMPLEXITY IN THE HEALTH SPACE

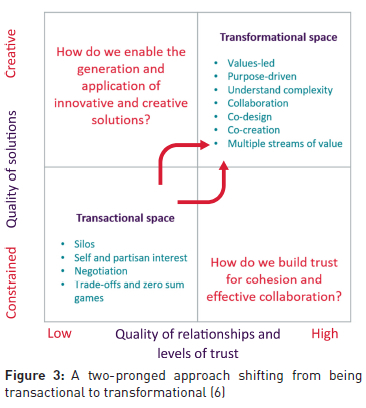

In navigating the complexity, there are no simple or perfect solutions. Instead, solutions are multifaceted and involve various players with different perspectives and often different agendas. The baskets of solutions generated and applied are generally better or worse relative to each other. (2) In broad terms, a suite of solutions that create transactional approaches are usually not well-suited to addressing complex challenges, while those representing transformational approaches are.

In seeking the best suite of solutions, two critical drivers are proposed to shape the required paradigm shifts: the levels of trust and the quality of relationships between the different stakeholders and the quality of solutions brought to bear.(6-8). Each of these drivers has two extreme positions. Levels of trust may be high or low, and the solutions generated may be constrained or innovative and creative.

While the two drivers may have some interdependence, they are sufficiently discrete to form a two-by-two matrix, as shown in Figure 3.(6) Through this matrix, it is possible to explore a shift from transactional approaches to transformational ones.

The transactional space is characterised by low levels of trust between stakeholders, which leads to poor relationships and the generation and application of constrained solutions. Key features of this space include stakeholders working in silos and being driven by self or partisan interest. Conflict is dealt with through negotiation, and when successful, there are trade-offs and compromises. Where negotiations are unsuccessful, the courts are approached, and ultimately, there are winners and losers. Current approaches around the design and implementation of the South African National Health Insurance (NHI) Act 20 of 2023 aptly demonstrate the transactional space.(9) While the intent for universal health coverage is valid and in line with SDG 3, design of the Act has not been inclusive, and forced rather than collaborative implementation is unlikely to achieve the desired goals. Stakeholders are far apart and do not trust each other, various partisan interests are at play, and court actions will likely be used to address conflicting views and disputes. In another example, interactions between private healthcare funders and providers relating to the funding of conditions and the levels of care provided often reflect transactional approaches.

High levels of trust between stakeholders, good-quality relationships, with the generation and application of innovative solutions characterise the transformational space. Hallmarks of the space include stakeholders being values-led and purpose-driven, solutions being co-created, and interventions being used at linkages and dependencies within the complex system to create leverage with multiple value streams.(10-12)

In the NHI context, fraught with complexity, all stakeholders, particularly the right voices, should be sitting around the table to co-create innovative and creative solutions that are in the best interests of all.

Shifting from being transactional to transformational requires a two-pronged approach to build trust-based relationships across different constituencies and create the conditions needed to generate and apply innovative and creative solutions.

A PROPOSED PATHWAY TO ACHIEVING GOOD HEALTH AND WELL-BEING IN SOUTH AFRICA

The proposed pathway seeks to stimulate dialogue around critical perspectives influencing good health and well-being in South Africa.(6) It is unlikely to be a final or finished product but instead attempts to bring structure to the conversations, underpinned by a paradigm shift towards being transformational rather than transactional. Through the process of dialogue, it is anticipated that the pathway design will be further enhanced.

The preliminary pathway is shown in Figure 4.

Mobilising a shared understanding and commitment to addressing the South African healthcare challenge is a necessary starting point. This is underpinned by being values-led and purpose-driven to build trust, reframe existing paradigms, transcend partisan agendas, and begin a pursuit for the collective good.(7) This also entails embracing mutual benefit with shared risk and reward.(lO) A shared understanding and collective commitment create a platform for co-designing an enabling policy environment supported by innovative funding models for transformative impact. Through co-design and co-creation, we enable co-ownership of the solutions developed to address the grand and complex challenges within the healthcare domain.(10)

Health system strengthening cuts across people, processes, and the hard and soft infrastructure required for broadened access and high-quality healthcare delivery. Building people capability would focus on technical capacity building across all disciplines in the field of health, as well as competencies from other fields such as leadership, governance, economic modelling, and complex systems thinking. An integrated approach is needed to leverage shared or complementary resources across public, private, and academic sectors. Targeted groups would include women, children, the elderly, and other vulnerable groups. In contrast, priority disease categories would consist of infectious diseases, physical trauma, mental wellness, and the growing epidemic of lifestyle-related diseases.

Finally, within this pathway, excellence in knowledge management enables us to monitor, evaluate, learn, improve, and accelerate impact as we ensure effective governance and pursue an iterative cycle of improved health and well-being.

CONCLUSION

The health challenges facing South Africa are complex and multifaceted. Current transactional approaches will not ensure healthy lives and promotion of well-being for all. Notwithstanding the challenges that seem intractable and unsurmountable, South Africa has the requisite talents and resources to achieve this set of aspirations. It, however, calls for fundamental paradigm shifts that enable us to move from transactional individualism to transformational collectivism by applying innovative, creative, and integrated approaches. Making the paradigm shifts will probably be the most difficult challenge, but once overcome, lofty aspirations can turn into reality.

REFERENCES

1. United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. 2015. New York: United Nations; 2015. Available from: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda [ Links ]

2. Rittel HWJ, Weber MM. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973; 4(2):155-169. [ Links ]

3. University of Pretoria. UP sustainable development report. 2019. Pretoria: University of Pretoria; 2020. Available from https://www.up.ac.za/media/shared/520/2021/up-2020-21-sustainable-development-report-final-s.zp225136.pdf [ Links ]

4. University ofPretoria. UP SDG progress report. 2020. Pretoria: University of Pretoria; 2021. [ Links ]

5. World Health Organisation [Internet]. One health; [updated 2023 October 23; cited 2024 December 4]. Available from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/one-health [ Links ]

6. Chicksen B, Cole M, Broadhurst J, et al. Embedding the sustainable development goals into business strategy and action. Cape Town: University of Cape Town; 2018. [ Links ]

7. Shaw RB. Trust in the balance: building successful organizations on results, integrity, and concern. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc; 1977. [ Links ]

8. Martin R. The design of business: why design thinking is the next competitive advantage. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing; 2009. [ Links ]

9. Public law: National Health Insurance Act 20 of 2023. (2024). [ Links ]

10. London T, Hart S. Next generation business strategies for the base of the pyramid. 2nd ed. New Jersey: Pearson Education Inc.; 2011. [ Links ]

11. Pralahad CK, Ramaswamy V. The future of competition: co-creating unique value with customers. Boston: HBS Press; 2004. [ Links ]

12. Rumelt R. Good strategy/bad strategy: the difference it makes and why it matters. London: Profile Books; 2011. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Brian Chicksen

brian.chicksen@up.ac.za