Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Dental Journal

On-line version ISSN 0375-1562Print version ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.74 n.4 Johannesburg May. 2019

https://doi.org/10.17159/2519-0105/2019/v74no4a3

RESEARCH

Oral health-related knowledge, attitudes and practices of adult patients in Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality, South Africa

MM ModikoeI; M ReidII; R NelIII

IBA (Nursing), M Nursing, Lecturer, Free State School of Nursing. University of the Free State, South Africa. ORCID Number: 0000-0002-4957-991

IIBCur, BA Cur, Clinical Nursing Science, Health assessment, treatment and care, M(Nursing), PhD(Nursing), Lecturer, School of Nursing. University of the Free State, South Africa. ORCID Number: 0000-0002-1074-1465

IIIMMedSc (Biostatistics), Lecturer, Biostatistics, School of Biomedical Sciences. University of the Free State, South Africa. ORCID Number: 0000-0002-3889-0438

SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION: Planning and implementation of oral health education is of more value when oral health-related knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) are known

AIM: To assess and describe oral health-related KAP of adult patients in the Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality using the theory of planned behaviour

METHODS: A quantitative descriptive design was used and data were collected from a sample of 207 adult oral health patients using a questionnaire based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB

RESULTS: Positive responses by participants towards oral-related KAP were regarded as strengthening oral health-related practices. Oral health-related knowledge as reflected by participants' behavioural beliefs (93.7%), normative beliefs (81.1%), subjective norms (70%) and perceived behavioural control (71.9%) strengthened oral health behaviours positively. Participants' control beliefs did not strengthen oral health practices. Participants' attitudes (62.3%),intention (98.5%), actual behavioural control (99%) and behaviour (95.1%) strengthened oral health-related practices

Adult patients generally portrayed behavioural beliefs, normative beliefs, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control that strengthened oral health behaviours positively.

CONCLUSIONS: Understanding oral health-related KAP of adult patients would assist role players in the health sector to plan evidence based oral health education. Healthcare workers should be sensitive to the KAP of adult patients receiving oral health-related care

Keywords: Oral health, knowledge, attitudes, practices, theory of planned behaviour.

INTRODUCTION

The mouth is an indicator of the state of a person's oral and general health.1 Oral health is illustrated by the ability to speak, smile, chew, swallow and use different facial expressions without pain and discomfort.

This favourable status may therefore be realised when there is an absence of disorders that affect different structures of the mouth, such as those causing possible pain, mouth lesions, tooth decay and gum disorders.2,3 World-wide, oral health disorders are reported to affect almost all adults at some point in their lives and these disorders rank among the top 100 conditions known to affect the quality of life.4 Poor oral hygiene, diet and smoking are some of the risk factors causing oral health disorders in all corners of the world.5 In Africa, poverty is one of the determinants of oral health disorders, as it predisposes people to a lack of information and poor lifestyle choices.6

Poor oral health-related information and lifestyle choices can be improved by integrated oral health promotion strategies with the involvement of government, the private sector, community health workers and the community.7 Oral health promotion strategies include oral health education, good nutritional guidance and increased intake of fluoride.8 It is often expected that oral health promotion strategies should lead to the acquisition of knowledge, skills and attitudes that result in behavioural change.7 However, behavioural change does not necessarily flow from receiving information during health promotion, as has been the case in other oral health-related studies.9

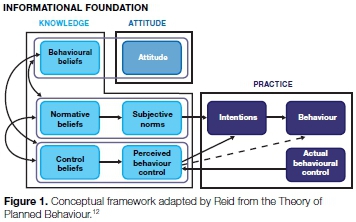

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) aims to explain how various elements play a role in predicting be-haviour.10 According to the TPB, behaviour is primarily determined by a the intentions of a person to perform certain behaviour. Intention is independently influenced by a person's attitude towards the behaviour and underlying beliefs and norms.11

The interactions between these elements are in actual fact not linear, but reflect a complex network. One can however still derive from Figure 1 that attitude, depicting a person's positive or negative evaluation of certain behaviour, is informed by behavioural beliefs. The behavioural beliefs in turn reflect the outcomes of performing behaviour.

Subjective norms on the other hand are influenced by the normative beliefs of significant others in a person's life. Perceived behaviour control, on the other hand, refers to the person's assessment of his or ability to perform the behaviour. It is important to note that a person's beliefs and norms may not necessarily be "correct" but they would still inform the intention to perform or not to perform, specific behaviour.

In this study the TPB was applied to assist in describing the knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) of adult oral health patients in the Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality.10,12 Beliefs and norms of these patients constituted the informational foundation, which is associated with the knowledge element in this study, whereas intention together with actual behavioural control is associated with practice. Figure 1 depicts the structuring of KAP elements within the TPB.12

The majority of patients (71.4%) in South Africa in the first instance visit public health services.13 In an effort to provide a comprehensive service, health promotion is therefore provided at different settings.13 Oral health promotion therefore forms part of the activities lead by ward-based outreach teams.14

Oral health promotion should mainly focus on encouraging healthy behaviours.15 Studies have shown that when the KAP's of people are known, oral health promotion programmes become relevant and effective,16 and even more so when such a study is embedded in a behaviour prediction model such as the TPB. This combination may provide a possible structure for health promotion in a municipal areas such as Mangaung.

METHODOLOGY

The study made use of a quantitative descriptive design with data being collected over a period of four weeks in 2015 by means of a questionnaire, which was adapted from the WHO Oral Health Questionnaire for Adults and the TPB Questionnaire.17,18

Participants were adult patients from Mangaung who were receiving oral health care at one of Ave public health care facilities. These included community health centres (CHCs) and district hospitals providing oral health care.

The public health establishments were identified with the assistance of the provincial oral health coordinator. A proportional sample was determined by a biostatis-tician with the assistance of a statistical programme, ensuring that patients were proportionally represented from amongst the Ave public health establishments.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the University of the Free State (ECUFS NR 65/2015) and permission from the Free State Department of Health.

The questionnaire was prepared in English and translated into Sesotho and Afrikaans. The questionnaire comprised 19 questions, presented in four parts, namely Demographic and Biographical information as Part 1, Knowledge regarding oral health as Part 2, Attitudes as Part 3 and Practices as Part 4.

A pilot study (n = 13) was conducted, and those data were subsequently included in the main study since no changes were made to the questionnaire and the participants were from the sample population. This lead to a total of 207 participants being included in the study.

The researcher and two trained fieldworkers collected data from participants at the five facilities, namely Botshabelo District Hospital dental clinic (n=48), Dr JS Moroka District Hospital dental clinic (n=30), Heidedal CHC (n=49), Mangaung University Community Partnership Programme CHC dental clinic (n=31), and the National Hospital CHC dental clinic (n=49).

The data were captured twice using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet before being handed over to the biosta-tistician for analysis. Descriptive statistics, namely the frequency of the responses of participants leading to positive oral health-related behaviours and/or practices, were given with percentages for categorical data, and the medians and percentiles for numerical data were calculated. As recorded by the TBP, a higher percentage in the responses generally indicates a positive oral health-related behaviour and/or practice.

RESULTS

Demographic and biographic data

Demographic and illness data of participants are given in Table 1. A total of 207 adult patients participated in the study, aged 18 to 78 years with a median of 33 years. Participants were predominantly females, speaking Sesotho and most having not completed secondary schooling. Although participants attended an oral health service, they did not perceive themselves to be ill, with tooth-related problems being the most prevalent reason for visiting an oral health service.

Knowledge

The results of the assessment of the oral health-related knowledge of the participants, covering behavioural beliefs, normative beliefs, control beliefs, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control in accordance with TPB are presented in Table 2. In Table 3, knowledge responses are summarised, reflecting a high percentage of positive responses to behavioural beliefs, normative beliefs, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control.

Control beliefs were assessed with open-ended questions which were thematically coded. Almost 41% of the participants did not know any teeth and/or gum disorders with the majority not knowing teeth and/or gum disorders that could or could not be prevented (Table 2). Table 3 reflects the high percentages of other knowledge elements which strengthen oral health-related behaviours and practices.

Attitudes

Table 4 reflects the attitudes of participants which could lead to positive oral health-related behaviour and/or practices. Although not shown on the Table, more than half (62.3%) of the responses were positive towards oral health-related behaviours with a median of 50% (range 14.3%-92.9%). The findings therefore imply that the majority of participants projected positive attitudes towards oral health-related behaviours. As predicted by the TPB, positive behavioural beliefs towards oral health lead to positive attitudes towards oral health.

Practices

The reports of the participants on their oral health-related practices are presented as their intentions, actual behavioural control and behaviour in accordance to the TPB (Table 5). In Table 6, practice responses are summarised and the calculation reported in percentages. The results are again aligned to the TPB since a positive attitude had a favourable influence on oral health-related practices. The subjective norms and perceived behavioural control of the participants further supported positive oral health behaviours and/or practices.

DISCUSSION

Demographic and illness characteristics of participants

The ages of participants ranged from 18 to 78 years, the majority being females, in line with the gender demographics of South Africa.19,20,21 Sesotho is the language spoken most often in households in the Free State Province (53.2%),22 confirmed in this study. The questionnaire was presented in Sesthoto and English.

The findings that numerous participants did not complete secondary schooling and that there were those who never attended school, might be attributed to the previous apartheid government laws and a lack of development affecting people in disadvan-taged communities.23

The predominance of tooth-related problems experienced by participants also occurred in Jordan when Khamaiseh and Al Bashtawy evaluated oral health KAP among secondary school students.15

Participants (8.6%) in the current study who had never been seen by a healthcare worker for oral care may have missed opportunities for accessing oral health information that could have led to improved oral health behaviours and/or practices, as found in the study by Molete, Yengopal and Moorman.24

Knowledge

Behavioural beliefs

Although the participants' behavioural beliefs were generally positive towards oral health behaviours, a few participants indicated beliefs that do not strengthen positive oral health practices.

Relieving toothache by placing Disprin on the painful tooth emerged as one such belief, which instead of addressing the pain may result in damage to the epithelium.25

Normative beliefs and subjective norms

The alignment of normative beliefs and subjective norms supported the TPB in this study. These findings are comparable to the findings by Anderson, Noar and Rogers who applied the TPB to determine dental check-ups among the young adults in Midwestern Universities, USA. The findings revealed that normative beliefs influenced the young adults' subjective norms towards regular dental check-ups.26

Control beliefs and perceived behavioural control

The apparent ignorance of participants of actions that they could take that would offer some control over their own oral health is of import. The reason may be attributed to their poor knowledge regarding tooth and gum disorders that can or cannot be prevented. The findings in this study regarding this poor knowledge differ from findings in Tehran where the KAP of adults towards periodontal health were determined.

Most of those study participants demonstrated a knowledge of how gum disorders could be prevented.27 The perspectives of adults in Maryland regarding tooth decay were also assessed and many participants mentioned how tooth decay could be prevented.28 If participants from the reported study had such knowledge, they would perceive themselves as having control over factors influencing and strengthening their behaviour and/or practices related to oral health.

When it came to perceived behavioural control, most of the participants recorded responses which were positive towards oral health behaviour and/or practices; however, negative perceived behavioural responses were revealed in the use of traditional and unhygienic behaviours and/ or practices. The use of ash reported in this study is not surprising since it was also highlighted as a common practice in a recent study which determined oral hygiene knowledge and practices among the Dinka and Nuer people from Sudan.29

Cleaning materials, such as charcoal and soap, were reported as being used in the North West Region of Cameroon when gum health and the oral hygiene practices of school children were determined.30 It would be expected that this would also be the practice of adults in the community.

Unhygienic flossing items were also identified in a KAP study in Nigeria where 35.6% of participants used wooden toothpicks, 25.2% plastic toothpicks, 20% splinters from broomsticks and 12.4%, pins.31 Continual performance of these behaviours and/or practices may lead to injuries and damages in the mouth reflecting that positive oral health practices did not take place.

The perceived behavioural control reported in this study contradicts the TPB in the sense that participants did not consider themselves to have control over factors that could determine their behaviours and/or practices regarding oral health. There was a lack of alignment between control beliefs and perceived behavioural control. A similar finding was made by Starkel in Chicago, USA, who tested the ability of the TPB to predict dental visit behaviour in adults. Respondents in the Chicago study had positive control beliefs towards dental visits but their perceived behavioural control towards dental visits was insignificant in influencing their intentions.32

Attitudes

The positive attitudes in this study were consistent with the TPB since participants reflected positive behavioural beliefs which strengthened positive oral health behaviours and/or practices. French and Cooke also noted that influence on attitudes and the performance of behaviour.33 Although negative attitude responses emerged from some participants, the mainly positive attitudes of participants towards oral health in this study strengthened their intentions, resulting in positive performance of oral health behaviours and/or practices, as aligned to the TPB.

These findings are supported by Domitrescu, Wagle, Dogaru and Monalescu who tested the efficiency of an extended model of TPB in predicting the intentions to improve oral health behaviours in first-year undergraduate students at the University of General Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, Romania.34 They found attitude to be a strong determinant of intention.

Similar findings were reported by Starkel who reported that the favourable attitudes of respondents towards dental visits led to the intention to actually visit the dentist.32 Positive attitudes towards the importance of oral health were strongly associated with oral health self-care behaviour among nursing home personnel in rural Virginia, USA.35

Practices

Intention, actual behavioural control and behaviour

The findings of this study support the TPB in that a positive attitude, perceived behavioural control and specific subjective norms strengthened positive intentions towards oral health behaviours and/or practices. Attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control were found by Huda, Rini, Mardoni and Putra to lead to intentions in terms of Islamic religious obligations and similar conclusions were drawn in a study by Cooke, Dahdah, Norman and French that applied the TPB to predict practices in alcohol consumption.36,37

Similar findings were reported when Van den Branden, Broucke, Leroy, Declerck and Hoppenbrouwers tested the TPB in oral health-related behaviours of parents towards their preschool children in Belgium,38 their finding was that attitudes, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms determined the intentions and performance of oral health behaviours. In contrast, French and Cooke found that only attitude and subjective norms predicted intention, but that perceived behavioural control did not influence intention.33

When Knabe applied the TPB to an online course in public relations, she found that attitude, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control led to an intention, with subjective norms having a much greater influence than attitude and perceived behavioural control.39

The present study has found that only behavioural and normative beliefs were closely related to the attitude and subjective norms of the participants. However, control beliefs seemed not to have an influence on perceived behavioural control.

These findings differ from those of Haydon, Obst and Lewis where the beliefs of women's intentions to consume alcohol were assessed.40

Those authors found that behavioural beliefs, normative beliefs and control beliefs influenced the intention of their subjects to drink alcohol. Behavioural beliefs, normative beliefs and control beliefs were all associated with adherence to antidiabetic treatment in Brazil when salient beliefs regarding the treatment were analysed according to the TPB.41

Positively strengthened intentions and actual behavioural control recorded in the results presented in the present study, influenced the planned performance of oral health-related behaviours and/or practices, as predicted by the TPB. A study in Belgium also found that the intentions of parents led to the performance of oral health-related behaviours.38Table 5 presents the translation of participants' intentions and actual behavioural control into behavioural performance. An example here is the response of participants towards the use of a toothbrush and toothpaste to clean the mouth and rinsing the mouth with salty water when mouth sores occur.

Limitations

The results of this study cannot be generalised to public oral health establishments in South Africa. However, they can provide insight into the oral health-related KAP of adult patients in Mangaung Metro and the Free State. Whilst the structured questionnaire was based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), it has not as yet been validated.

CONCLUSION

This study has shown that adult patients generally portrayed behavioural beliefs, normative beliefs, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control that positively strengthened oral health behaviours. Control beliefs in this study did not strengthen oral health behaviour.

Positive attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control strengthened adult patients' intentions towards enhanced performance of oral health-related behaviours and/or practices. Lastly, adult tpatients' intentions and actual behavioural control led to the performance of oral health-related behaviours and/or practices.

The outcomes of this study can be used to inform the planning of integrated oral health promotion strategies, specifically in Mangaung and the Free State Province of South Africa. It would be beneficial to focus on the control beliefs of adults, since this may strengthen positive oral-health related behaviour. The TPB-based questionnaire used in this study could guide future interventions that are aimed at improving oral health practices of patients. The findings of this study may be used as a catalyst for further oral health-related research.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge financial support by the National Research Foundation.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

ACRONYMS

CHC: Community Health Centre

KAP: Knowledge, Attitudes And Practices

PHC: Primary Health Care

TPB: Theory of Planned Behaviour

References

1. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Mouth problems and HIV, 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.nidcr/oralhealth/topics/ [Accessed 10 March 2016]. [ Links ]

2. Federation Dentaire Internationale [FDI] World Dental Federation. FDI unveils new universally applicable definition of oral health. 2016. Retrieved from: http://www.fdiworldental.org/media/pressreleases/latest-press-release. [Accessed 25 January 2017]. [ Links ]

3. World Health Organization. Oral Health, 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs318/en/ [Accessed 21 February 2014]. [ Links ]

4. Marcenes W, Kassebaum N J, Bernabé E, et al. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990-2010: A systematic analysis. 2013. Retrieved from: http://jdr.sagepub.com/content/early/2013/002203451349016 [Accessed 9 May 2016]. [ Links ]

5. Sheiham A. Oral health, general health and quality of life. Bull WHO. 2005; 83(9):644-5. [ Links ]

6. Thorpe S. Oral health issues in the African region: Current situation and future perspectives. J Dent Educ. 2006; 70(11): 8-15. [ Links ]

7. World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Promoting Oral Health in Africa: prevention and control of oral diseases and noma as part of essential non-communicable disease intervention. Brazaville: World Health Organization [WHO] Regional Office for Africa, 2016. [ Links ]

8. Petersen P E. Challenges to improvement of oral health in the 21st century- the approach of WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Int Dent J. 2004; 54(6):329-43. [ Links ]

9. Mndzebele S, Kalambay J. 2014. The influence of oral health knowledge and perceptions on dental care behaviours among adults attending treatment at Berea Hospital, Lesotho. AJPHERD. 2014; 1(2):385-95. [ Links ]

10. Ajzen I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991; 50:179-211. [ Links ]

11. Ajzen I, Joyce N, Sheikh S, Cote N G. Knowledge and prediction of behavior: The role of information accuracy in the theory of planned behavior. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2011; 33(2):101-17. [ Links ]

12. Modikoe MM, Reid M, Nel M. Oral health-related knowledge, attitude and practices [KAP] of adult patients in the Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality, South Africa. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State, 2017 in press. [ Links ]

13. World Health Organization. Primary Health Care report of the international conference on Primary Health Care - Alma Ata USSR 6-12 September, Geneva: World Health Organization, 1978. [ Links ]

14. Engelbrecht MC, Van Rensburg HCJ. Primary health care: Nature and state in South Africa. In: Van Rensburg HCJ, ed. Health and Health Care in South Africa. Pretoria: Van Schaik, 2012: 483-529. [ Links ]

15. Khamaiseh A, Al Bashtawy M. Oral health knowledge, attitudes and practices among secondary school students. Br J Sch Nurs. 2013; 8(4): 194-9. [ Links ]

16. Amith H, D' Cruz A, Shirahatti R. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding oral health among the rural government primary school teachers of Mangalore, India. J Dent Hyg. 2013; 87(6):362-9. [ Links ]

17. Ajzen I. Constructing a Theory of Planned Behavior questionnaire. 2006. Retrieved from: http://people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf. [Accessed 10 November 2014]. [ Links ]

18. World Health Organization. Oral health. 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs318/en/ [Accessed 21 February 2014]. [ Links ]

19. Statistics South Africa. Mid-year population estimates 2015, Pretoria: Statistics South Africa, 2015. [ Links ]

20. Statistics South Africa. Gender statistics in South Africa 2011, Pretoria: Statistics South Africa, 2013. [ Links ]

21. Nair B, Singh S. Parental perspectives on self-care practices and dental sealants as preventive measures of dental caries. S Afr Dent J. 2016; 71(4): 154-8. [ Links ]

22. Statistics South Africa. Census 2011 Census in brief, 2012, Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. [ Links ]

23. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Adult literacy and skills training program South Africa. 2012. Retrieved from: www.unesco.org/uil/litbase/?menu=9&programme=52 [Accessed 17 March 2017]. [ Links ]

24. Molete M P, Yengopal V, Moorman J. Oral health needs and barriers to accessing care among the elderly in Johannesburg. S Afr Dent J. 2014; 59(8):352-7. [ Links ]

25. American Dental Association. Dental emergency. Retrieved from: http://www.mouthhealthy.org/en/az-topics/d/dental-emergencies [Accessed 7 March 2017]. [ Links ]

26. Anderson CN, Noar SM, Rogers BD. The persuasive power of oral promotion message: A theory of planned behavior to dental checkups among young adults. Health Communication 2013, 28:304-13. [ Links ]

27. Gholami M, Pakdaman A, Jafari A, Virtanan J. Knowledge of and attitudes towards periodontal health among adults in Tehran. East Mediterr Health J. 2013, 20(3):196-202. [ Links ]

28. Horowitz A, Kleinman D, Child W, Maybury C. Perspectives of Maryland adults regarding caries prevention. Am J Pub Health . 2015; 105(5):58-64. [ Links ]

29. Willis MS, Bothun RM. Oral hygiene knowledge and practice among Dinka and Nuer from Sudan to U.S. J Dent Hyg. 2011; 85(4):306-15. [ Links ]

30. Azodo C, Agbor A. Gingival health and oral hygiene practices of school children in North West Region of Cameroon. BioMed Central Research Notes 2015; 8(385): 1-6. [ Links ]

31. Ehizele A, Chiwuzie J, Ofili A. Oral health knowledge, attitude and practices among Nigerian primary school teachers. Int J Dent Hyg. 2011; 9: 254-60. [ Links ]

32. Starkel R. Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior to dental visits behavior. Chicago: Loyola University, 2015 in press. [ Links ]

33. French DP, Cooke R. Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to understand binge drinking: the importance of beliefs for developing interventions. Br J Health Psychol. 2012; 17(1):1-18. [ Links ]

34. Domitrescu A, Wagle M, Dogaru B, Manolescu B. Modeling the Theory of Planned Behavior for intention to improve oral health behaviors: the impact of attitudes, knowledge and current behavior. J Oral Sci. 2011; 53(3): 369-77. [ Links ]

35. Wiener RC, Meckstroth R. The oral health self-care behavior and dental attitudes among nursing home personnel. J Stud Soc Sci. 2014; 6(2):1-12. [ Links ]

36. Huda N, Rini N, Mardoni Y, Putra P. The analysis of attitudes, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control on Muzakki's intention to pay zakah. Int J Bus Soc Sci., 2012; 3(22): 271-9. [ Links ]

37. Cooke R, Dahdah M, Norman P, French D P. How well does the Theory of Planned Behaviour predict alcohol consumption? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev. 2016; 10(2): 148-67. [ Links ]

38. Van den Branden S, Van den Broucke S, Leroy R, Declerck D, Hoppenbrouwers K. Predicting oral health related behaviour in the parents of preschool children: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. Health Educ J. 2015; 74(2); 221-30. [ Links ]

39. Knabe, A. Applying Ajzen's Theory of Planned Behavior to a study of online course adoption in public relations education. Milwaukee Wisconsin: Marquette University, 2012. [ Links ]

40. Haydon H M, Obst P L, Lewis, I. Beliefs underlying women's intentions to consume alcohol. BMC Women's Health 2016; 16(36):1-12. [ Links ]

41. Januzzi FF, Rodrigues RCM, Cornélio ME, São-João TM, Jayme Gallani MCB. Beliefs related to adherence to oral antidiabetic treatment according to the Theory of Planned Behavior. Rev Latino-Am de Emfermagem 2014; 22(4):529-37. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Marianne Reid

School of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences

University of the Free State

P.O. Box 339, Bloemfontein 9300 South Africa

Tel: +27 (0)51 401 9747

Email: reidm@ufs.ac.za

1 Mahlodi M Modikoe - 60%

2 Marianne Reid - 30%

3 Riette Nel - 10%