Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy

On-line version ISSN 2411-9717Print version ISSN 2225-6253

J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. vol.118 n.6 Johannesburg Jun. 2018

https://doi.org/10.17159/2411-9717/2018/v118n6a1

INFACON XV: INTERNATIONAL FERRO-ALLOYS CONGRESS 2018

Changing nickel and chromium stainless steel markets - a review

H.H. Pariser; N.R. Backeberg; O.C.M. Masson; J.C.M. Bedder

Roskill Pariser Steel Alloys, UK

SYNOPSIS

This review covers the changing fortunes of the nickel and chromium markets, which are intimately tied to stainless steel production. Over the last few decades, growth in the stainless steel market has outpaced that of the carbon steel, aluminium, copper, and zinc markets, and as a result, demand for nickel and chromium has benefited. The emergence of China as the world's largest stainless steel producer - estimated at 54% of world supply in 2017 - means the country needs increasing quantities of chrome ore: Chinese imports increased by 29% year-on-year in 2017. The dynamics of the chrome trade are heavily skewed towards South Africa and China, but how long will this continue? The sheer size of China's stainless steel industry means that it is also the largest consumer of primary nickel, thanks to the industry's reliance on primary units, mostly in nickel pig iron. We estimate that stainless steel production accounted for 68% of global primary nickel demand in 2017, but this ratio is set to decline in the years ahead as the increased electrification of automotive transport leads to higher requirements for nickel in batteries.

Keywords: stainless steel, nickel, chromium, ferrochrome, scrap.

Introduction

Stainless steel remains the principal end-use for chromium and nickel units. Stainless steel is a generic term for corrosion-resistant alloy steels containing 10.5% or more chromium. In the AISI (American Iron and Steel Institute) classification of steels, stainless steel must contain 10% or more chromium; in the BSI (British Standards Institution) classification, it must contain 11.5% chromium or more. The addition of 10% chromium to a steel gives corrosion resistance in mild environments; additions of over 18% chromium give protection in more aggressive environments in the chemical, petrochemical, process, and power industries. Nickel is mostly added to improve the formability and ductility of stainless steel. In 1960, nickel demand in stainless steel was 219 kt, accounting for no more than 34% of the global nickel demand. This grew to a 68% market share in 2017, accounting for approximately 1470 kt of primary nickel. Alloying with these elements brings out different crystal structures in stainless steel to impart different properties in machining, forming, and welding.

Roskill Pariser presents a market review for the nickel and chromium stainless steel markets, with historical data as of 19 January 2018. The data presented in this paper is sourced from Roskill Pariser Steel Alloys and Roskill Information Services, unless stated otherwise. It includes certain statements that may be deemed 'forward-looking'.

Although we have made every reasonable effort to ensure the veracity of the information presented, we cannot expressly guarantee the accuracy and reliability of the estimates, forecasts, and conclusions contained herein. Accordingly, the statements in the presentation should be used for general guidance only.

Stainless steel

Stainless steel has been one of the fastest-growing metal products over the past decades, outperforming carbon steels and aluminium as well as other base metals, owing to rapid growth in demand from sectors such as construction, transportation, and consumer products (Figure 1).

Stainless steel demand in the 1950s to 1970s was defined by the post-war reconstruction period. Before the 1960s, the US stainless steel market was leading global development, until a few stainless steel producers in Japan and in Europe steadily increased their market shares to overtake the USA in the late 1960s. Prior to 1980 China had been sporadically melting stainless steel, but only became a noteworthy supply source from the year 2000 onwards.

In recent years, China has developed into the global market leader, thanks to the rapidly growing Asian stainless demand and China's capability of meeting this demand with 'unconventional' raw material usage - in particular nickel pig iron (NPI), but also due to state-supported capital expenditure on modern stainless steelmaking equipment.

Japan has become a technology leader in a range of stainless steel applications for the automotive industry and various other consumer goods, while European stainless steel producers have focused on a wide range of applications in equipment used in demanding environments such as chemical plants, power stations, and other industrial applications, as well as household appliances, consumer goods, and automotive parts.

In the USA, market performance has been relatively steady over the last five years. In contrast, the performance in Japan has been more volatile, while China's stainless output resumed its upwards path in 2016 and 2018, following a modest decline in 2015. In 2017, we estimate that China accounted for 54% of world crude stainless steel production.

End-use structure ofstainless steel

It is a hopeless task quantifying the thousands of different applications for stainless steels. The top five end-use segments, which we outline here, account for some 77% of the recent markets.

The dominant end-use applications for stainless steels are still in machinery and equipment, followed by basic metals as well as fabricated metal products. These three product groups account for some 58% of the aggregated market volume in industrialized countries, while in developing and emerging countries their share is as high as 69% (Figure 2). Motor vehicles play an important role in industrialized countries, accounting for some 12.4% while their ratio in developing and emerging countries is not more than 5.3%.

One market segment with a strong regional application is architecture, building, and construction (ABC). Globally, ABC accounts for some 13% of stainless steel consumption, but we observe wide variations on a regional basis. Japan, for instance, has traditionally had a strong preference for stainless steel roofing and bath tubs, but these applications are rarely found in European countries.

We follow quarterly stainless supply and demand volumes, which show an almost steady performance reflecting the stabilizing impact from the steady growth performance of China. In earlier decades, the market went through significant fluctuations due to stocking and de-stocking activity. The two diagrams in Figure 3 illustrate the developments in stainless steel demand over the last seven years. Demand growth in developing and emerging countries amounts to some 6.3% annually, which is more than twice as fast as in industrialized countries.

Stainless steel price and market balance

One of the key reasons for the steady demand growth in stainless steel is relative price stability. Stainless steel prices are published by various sources, but we found that our own evaluation of service centre sales prices provides a more realistic picture of the market over the past 6-8 years.

In our opinion, the lack of reliable price information is a major handicap for the global stainless steel market. Modern price hedging under the prevailing circumstances is hardly possible.

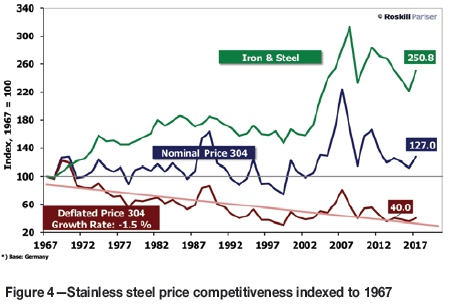

We have followed stainless steel prices regularly since 1967, the first year that a generally accepted definition for stainless steel was introduced. Since then, nominal stainless steel prices have remained within a narrow range, close to the 1967 base year (Figure 4). Major price increases occurred during periods of high nickel prices, as was the case in 19891990 and again two decades later in 2008-2010. However, stainless steel prices have usually weakened again after the short high-price periods. In contrast, since 2005 stainless steel prices have stabilized above the base year value in a range of some 120-130 index points.

A price comparison with other commodities shows that iron and steel prices have outgrown stainless steel prices significantly, while prices for non-ferrous alloys, which include mostly copper alloys and aluminium, have also outperformed stainless steel.

Nickel

Ihave called it "Nickel"': Axel Fredrik Cronstedt, 1722-1765

China has developed into the largest market for primary nickel. The country is forecast to account for almost 57% of global nickel consumption in 2018. The second largest regional market is the European Union accounting for 13.5%, whereas markets combined under 'Other Asia' rank third with a global share of almost 10%. All other regions remain well below the 5% market position.

Primary nickel markets have been divided into Class I and Class II materials, and chemical products used in the battery industry. We forecast the use of primary nickel in batteries to rise by an average of over 20% per year between 2017 and 2027. The scale of growth reflects not only the expect size of the market a decade from now, but also its current small size. The main driver behind the forecast increase in this market's size is the electrification of the automotive industry. Nickel demand will benefit not only from the substitution of internal combustion engines in cars by lithium-ion batteries, but also from changes in battery chemistries towards increasing concentrations of nickel, which will give the market an additional boost, primarily from nickel sulphates. The details of this research have been recently published in Roskill's broader battery materials analytics and bespoke research.

The changing product mix is marginally influencing the Class I nickel segment, including carbonyl nickel pellets, electrolytic nickel cathodes, and briquettes, expanding by only 1.2% per annum over the same period, and reaching a level of some 1 Mt by 2027.

Class II materials are primarily applied for stainless steel melting and include the classical ferronickel qualities, but also utility nickel, nickel oxide sinter, and NPI. This product group is expected to expand by 4.9% per annum between 2017 and 2027 to 1.7Mt.

Overall, nickel supply might need to reach some 3.1 Mt by 2027, 1 Mt more than in 2017, to keep up with rising demand, particularly from the batteries sector. For 2018 we assume a market volume of nickel at approximately 2.1 Mt. Electrolytic nickel cathodes should remain the main product group, followed closely by NPI, both accounting for around 600 kt. Ferronickel is the third largest product at 450 kt, with nickel briquettes accounting for just over 200 kt. The balance includes nickel oxide sinter, carbonyl nickel pellets, and sulphates (Figure 5).

Nickel pig iron in China

The development of the NPI market enabled China to feed its rising stainless steel production. NPI output grew strongly between 2005 and 2014 but slowed from 2015 onwards, primarily due to lack of sufficient feed material. Production has moved back to over 100 kt per quarter recently as the ore availability has started to improve.

Over the years, Chinese producers of NPI have changed their product mix. Almost 80% of the current output consists of high-grade materials containing more than 10% Ni, while low-grade materials with no more than 2% Ni have diminished to approximately 20%. Medium-grade NPI, containing 4-6% Ni, was popular at the beginning of the decade, when it accounted for some 30% of the total NPI output, but this market has virtually ceased to exist, falling below 1% in 2016.

Nickel price developments since January2016

Nickel prices went into 2016 at particularly low levels, of around US$8 000 per ton. However, as the market began to tighten after several years of chronic oversupply, prices began to improve. In the second half of 2016, prices were comfortably over the US$10 000 per ton level, and traded within a range of around US$9 000-11 000 per ton until the third quarter of 2017 (Figure 6). Since then, however, the growing realization that the strong prospects for nickel demand in batteries should sustain strong demand growth, coupled with a continued market deficit, has supported a further price appreciation. By early 2018, the LME nickel cash price had approached the US$13 000 per ton level. One factor that could hold back prices is the stock that was accumulated during the recent period of sustained market surpluses.

Chromium

Without chromium there is no stainless steel!

From a stainless steels producer's point of view, two types of chromium ferroalloys are to be distinguished: charge chrome and the high-carbon (HC) ferrochrome (FeCr). In a stainless steel mill, most of the required ferrochrome is added directly into the electric arc furnace (EAF), with the stainless producer having the choice of adding either charge chrome or HC ferrochrome. When the steel has been decarburized and tapped from the EAF, the stainless producer will then usually add a small amount of medium-low carbon (MLC) ferrochrome to 'trim up' the chrome specification of the steel.

There are usually significant differences between the levels of certain impurities present in charge chrome vis-a-vis HC ferrochrome, especially silicon. The scrap ratio used in stainless steel mills has a significant effect on the type of ferrochrome consumed, as there are almost always far more impurities in all grades of ferrochrome than in stainless steel scrap. The use of scrap also has significant impacts the quantity of primary ferrochrome consumed.

Charge chrome contains some 50% chromium and 6-8% carbon, and is primarily applied for stainless steel melting. In Asian countries - particularly in China and India - HC ferrochrome grades are predominantly produced, typically containing 60-70% chrome and varying carbon contents.

Historically, charge chrome production has significantly outweighed HC ferrochrome production in terms of tonnage, following a growth of 7.3% per annum since 2000, whereas HC ferrochrome grew slightly slower at 5.4% per annum (Figure 7).

Power supply restrictions have favoured the use of HC ferrochrome, which is expected to grow at 3.3% per annum in the long term to 2030, compared to a 2.2% per annum growth in production of charge chrome.

Chrome ore

World mine production of chromite closely follows trends in ferrochrome production, which accounts for nearly 90% of consumption. Chrome ores are mined globally, but output is highly concentrated in terms of both geographical area and producing countries. Since 2007, the supply volumes have expanded by 3.6% annually, and are expected to reach almost 37 Mt in 2018.

Five countries produce more than 1 Mt/a of chromite. The expectations in 2018 are for South Africa to account for 60% of world output, including production from the UG2 Reef. Kazakhstan (13%), India (9%), Tukey (4%), and Finland (3%) are the other major producers. In total, these five countries accounted for 89% of chromite production. In South Africa, the contribution of UG2 chromite is estimated to account for over 10% of the annual supply.

Exports of chrome ore from South Africa reached almost 12 Mt in 2017, of which 11 Mt were directly and indirectly supplied to China. Shipments from South Africa ramped up in 2005-2008 as China's stainless steel boom set in, to an average 425 kt/month until 2012. Exports grew to 700 kt/month in 2013, but settled back to 590 kt/month in 2014, with less than 66% shipped to China in that year. Since 2015, monthly exports have increased sharply to an average of 970 kt by 2017.

The natural counterpart in the trade of chrome ore is China's rapidly expanding stainless steel industry, which obtains the bulk of its chrome ore from South Africa (approximately 72% in 2017). Minor chromite deposits are available in China, but the country's large stainless steel industry is dependent on imports. Other important suppliers of chromite to China include Turkey, Albania, and Pakistan (Figure 8). According to preliminary 2017 data, China's chrome ore imports expanded last year by 29%.

Ferrochrome production

We estimate last year's global ferrochrome production at approximately 11.7 Mt. Three countries produced more than 1 Mt of HC ferrochrome/charge chrome in 2017. China and South Africa together accounted for 68% of the total output, with Kazakhstan contributing a further 12%. India fell just below the 1 Mt mark (Figure 9). Ferrochrome prices have largely followed ore prices, although the changes both up and down have been more subdued.

In 2016, demand for ferrochrome increased to 11.1 Mt, followed by another expansion to 12.5 Mt in 2017. For the immediate future, in 2018 destocking is anticipated while demand is expected to decline by some 191 kt. Cutbacks are expected in the EU and various other countries, but China is likely to increase its consumption again.

Real ferrochrome demand is expected to increase by 3.6% to just over 12 Mt in 2018, while apparent consumption could rise by 4.4% to 12.3 Mt. A ferrochrome production of 12.5 Mt corresponds to a capacity utilization ratio of 74%, and leads to a minor supply surplus of 216 kt. However, if the supply is compared with 'real' demand, the surplus would be as high as 489 kt.

Production costs

For more than three decades our analysts have reviewed the global production costs on an ex-works basis. It appears that the most favourable conversion costs are identified for Kazakhstan, which has for years been the most competitive supplier. Kazakhstan is followed by South Africa's Glencore-Merafe joint venture, while Finland's Outokumpu Group ranks third. These three ferrochrome producers accounted for approximately half of the global production last year.

China's ferrochrome smelters are often not competitive and are relatively small by international standards. Typically, they rank 13th and 20th in this comparison. We presently estimate 2017 average 'C3 cost' (in US cents) at 66.7 US cents per pound Cr content and we expect a marginal increase to 66.8 US cents per pound Cr for 2018.

A direct 2017 cost comparison between South Africa and China reveals the following conclusions:

> South Africa has a cost advantage of 17.7 US cents per pound Cr when it comes to chrome ore input

> There is a disadvantage of 4.1 US cents per pound Cr for South Africa in reductants and other cost components

> Energy costs in South Africa are 7.4 US cents per pound higher than in China

> Semi-fixed costs of 5.94 US cents per pound compare with those of China at 2.89 US cents per pound

> Aggregated total direct cash cost in South Africa last year amount to 54.11 US cents per pound, while China's total cost amount to 75.76 US cents per pound.

Chrome ore prices

Ferrochrome prices follow broadly similar trends to chromite prices and are broadly cyclical, reflecting trends in the stainless steel industry, although with a time lag. The past two years have seen numerous price swings in the chrome ore and ferrochrome markets. Prices for chrome ore roughly quadrupled over the course of 2016, remaining extremely high in early 2017 before falling substantially in Q2 and bottoming out in Q3 (Figure 10). Prices have recovered slightly as of early 2018, with UG2 ore (42% CIF China) at US$206 per ton in January 2018, compared to the US$395 per ton high experienced in January 2017. Ferrochrome prices have largely moved in tandem with ore prices over this period, though the changes both up and down have been more subdued.

Stainless steel scrap

The neglected commodity

Stainless steel scrap is often ignored by those who monitor raw material markets. Stainless scrap is more complex than other raw materials and often follows its own trend. Last year, the global external scrap availability amounted to some 10.5 Mt, corresponding to approximately 85 kt of contained nickel units and some 180 kt of chromium units. In the case of China, stainless steel scrap played a role in the early 2000s, but this was before a domestic scrap market could be developed. China jumped onto NPI, which took over a similar role as scrap in Western countries. Frequent discussions with Chinese market participants provided a repeated answer: 'We do not understand the scrap market'. But for how long?

Countries within the EU form the largest stainless scrap market. The scrap market is highly organized and well developed, although Asia - in particular South Korea and Taiwan - followed the European expertise, whereas Japan went its own way, developing sophisticated sampling and sorting techniques. The USA has been the nucleus of the modern scrap industry and is still a major source of scrap supplies. As already stated, China lags behind this trend in scrap supplies. In part, this lag reflects the long life-cycle of stainless steel products. Chinese consumption of consumer goods only started to accelerate during the last 20 years. As such, in the future more scrap will be available in China. This should lead to a convergence in regional consumption of stainless steel scrap, with China's scrap utilization ratio creeping up towards the levels seen in Europe.

In traditional industrialized countries, prices for stainless steel scrap follow primary nickel prices. The so-called intrinsic value of important elements such as nickel and chrome is evaluated and these are typically traded at changing discounts below the primary price. Unfortunately, the number of competent scrap traders is diminishing, and for this reason it is more and more difficult to obtain consistent price information.

The same reasons apply for the evaluation of chrome units contained in stainless steel scrap. However, the available information is more consistent and transparent. The evaluation of chrome in stainless steel scrap is relatively stable at about 20% of the charge chrome price.

Conclusions

The market overview can be summarized as follows.

1. Ni-containing batteries might challenge the growing nickel requirements for stainless steel. Recycling of spent batteries becomes an issue.

2. Chrome markets are dominated by South Africa, but more chrome units are converted in China - how long will this remain so?

3. China's ferrochrome production has lost its competitive advantage in terms of production costs. Should China reduce production or even possibly exit from chrome conversion?

4. How long until China's scrap market begins to mimic those of the rest of the world? When scrap ratios increase because of the increased maturity of the market, ferrochrome consumption from primary sources will undergo a drastic change.

References

Roskill Pariser Stainless Steel. 2018. Stainless Steel & Alloys Weekly. https://roskill.com/market-report/stainless-steel-alloys-weekly/ [ Links ]

Roskill. 2018. Nickel: Global Industry, Markets & Outlook, 14th Edition. https://roskill.com/market-report/nickel/ [ Links ]

Roskill. 2018. Nickel Sulphate: Global Industry, Markets & Outlook, 1st Edition. https://roskill.com/market-report/nickel-sulphate/ [ Links ]

Roskill. 2018. Chromium: Global Industry, Markets & Outlook, 14th Edition. https://roskill.com/market-report/chromium/ [ Links ]