Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Historia

On-line version ISSN 2309-8392Print version ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.58 n.2 Durban Jan. 2013

ARTICLES ARTIKELS

Doing gender is unavoidable: Women's participation in the core activities of the Ossewa-Brandwag, 1938-1943

Charl Blignaut

Lecturer in history at the Potchefstroom Campus of NWU. His research interests include the history of the Ossewa-Brandwag; twentieth-century South African history; and the broad field of gender history. Email: 20312814@nwu.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Afrikaner women played a major role in the Ossewa-Brandwag (OB) movement in South Africa from 1939 to 1954. Women participated in a range of activities as part of the OB Women's Division. As an organisation born out of nationalism, women's agency was highly influenced by the so-called volksmoeder (mother of the nation) ideal. In order to understand how normative concepts of gender, as embodied in the volksmoeder, influenced the agency of OB women, this article looks at how women, through their "doing" of gender, contributed to construing and establishing the volksmoeder as a normative and symbolic gender concept in the Ossewa-Brandwag. Thus, it aims to throw light on how contemporaries, who were members of the Ossewa-Brandwag, understood and used gender difference in their societal organisation. By focusing on the core activities of the OB Women's Division, the article observes how OB women were actively involved in "doing" gender. The aim of this study does not involve an analysis of the volksmoeder per se, but of the relation between the performativity of gender and the nature of the volksmoeder as gender construction in this particular case of OB women.

Key words: Afrikaner women; volksmoeder; mother of the nation; Afrikaner nationalism; women's history; gender history; women; gender; Ossewa-Brandwag; South African history.

OPSOMMING

Afrikaner vroue het 'n belangrike rol in die Ossewa-Brandwag gespeel. Dié beweging het in Suid-Afrika bestaan tussen 1939 tot 1954. Vroue het deelgeneem aan 'n reeks aktiwiteite as deel van die OB Vroue-Afdeling. As beweging gebore uit Afrikaner nasionalisme, was vroue se agentskap hoofsaaklik beïnvloed deur die sogenaamde volksmoeder-ideaal. Ten einde te verstaan hoe normatiewe konsepte van gender, soos uitgebeeld in die volksmoeder, die agentskap van OB-vroue beïnvloed het, let hierdie artikel op hoe vroue, by wyse van hulle "doen" van gender, bygedra het tot die konstruksie en vaslê van die volksmoeder as normatiewe gender konsep in die OB. Die doel is dus op lig te werp op hoe tydgenote, wat lede was van die OB, geslagtelike verskil verstaan en gebruik het in hulle sosiale organisering. Deur te fokus op die kernaktiwiteite van die OB Vroue-Afdeling verken hierdie artikel hoe OB-vroue aktief besig was om gender te "doen". Daar word nie noodwendig 'n analise gemaak van die volksmoeder nie, maar daar word eerder gekyk na die verhouding tussen die "performatiewe" aard van gender en die normatiewe aard van die volksmoeder as gender konstruksie in hierdie spesifieke geval van OB-vroue.

Sleutelwoorde: Afrikanervrou; volksmoeder; Afrikaner nasionalisme; vrouegeskiedenis; gendergeskiedenis; vrouens; gender; Ossewa-Brandwag; Suid-Afrikaanse geskiedenis.

The 1930s saw several significant events, like the ascent of the Afrikaans media and the efforts of cultural entrepreneurs contributing to the rise of Afrikaner nationalism on a large scale. Hand in hand with these events there was also the construction of Afrikaner identity and the desiderata of both men and women, belonging to this ethnicity, to enunciate their nationalistic ideals on a public platform. One of the greatest opportunities for Afrikaners to participate actively in public in this "new national movement of the nation (volk) embodied in the nationalistic world view",1 was the Voortrekker Centenary Celebration of 1938 - the same celebration that led to the establishment of the radical-nationalist Ossewa-Brandwag (OB) movement.2

Afrikaner women played an important role in the centenary celebrations and in the Ossewa-Brandwag. Both were ideologically aligned in terms of gender when considering their articulation of the so-called volksmoeder (mother of the nation) ideal.3 Described by L. Vincent as "a highly stylised symbolic identity of ideal womanhood to which the ordinary women of the nation were meant to conform or at least aspire to",4 the volksmoeder "involved the emulation of characteristics such as a sense of religion, bravery, a love of freedom; the spirit of sacrifice; self-reliance; housewifeliness (huisvroulikheid); nurturance of talents; integrity; virtue and the setting of an example to others".5

During roughly the first half of the twentieth century, at least for women, the volksmoeder played the part in Afrikaner society of what J. Butler describes as "the terms that make up one's own gender ... outside oneself in a sociality that has no single author" and that "the viability of our individual personhood is fundamentally dependent on these social norms".6 As a gender construction, the volksmoeder can also be explained in terms of J.W. Scott's conceptualisation of gender. In line with Butler, Scott asserts that gender norms were "established as an objective set of references, concepts of gender structure perception and the concrete symbolic organisation of all social life."7 Of particular interest is Scott's emphasis on "normative concepts" as part of her elaboration of the definition of gender.8 She mentions that normative concepts laid down interpretations of the meaning of symbols like the volksmoeder and everything that she embodied which in turn limited and contained the metaphoric possibilities inherent in their symbolic enterprise.

These concepts were expressed in religious, educational, scientific, legal, and political doctrines and typically took the form of a fixed binary opposition, categorically and unequivocally asserting the meaning of male and female, masculine and feminine.9 The volksmoeder was indeed full of metaphoric possibilities when its symbolic nature is taken into account, but it was at the same time a normative concept10 not only found in the abstract, but found doubly so in everyday activities performed by women who were "acting in concert" with regard to the gender norms within the Afrikaner society at the time.11 One of the gendered concepts of Afrikaner nationalism was performed through Afrikaner women's participation in the general activities of the Ossewa-Brandwag Women's Division.

In order to understand how the normative concepts of gender, as embodied in the volksmoeder, influenced the agency of OB women, it is important to ask the following question: How did women, through their "doing" of gender, contribute to construing and establishing the volksmoeder as a normative and symbolic gender concept in the OB? Thus, it is the aim of this article to shed light on how contemporaries who were members of the Ossewa-Brandwag understood and used gender in their societal organisation. By focusing on the core activities of the OB Women's Division, this article observes how OB women were actively involved in "doing" gender.12

These activities included fundraising; acting as the symbolic inspiration for the OB as a whole; looking after the families and dependents of men who were interned during South Africa's participation in WW II; educating young girls; and becoming involved in a variety of cultural activities. Although these activities were performed throughout the existence of the OB, this article focuses on women's role in the period from 1938 to 1943.13 Furthermore, the aim of this study does not involve an analysis of the volksmoeder per se, but of the relation between the performativity of gender and the nature of the volksmoeder as gendered construction in the particular case of OB women. For this reason it is important to explain what is meant by "doing gender" and then to analyse how gender was "done" by women in the Ossewa-Brandwag.

In 1978, West and Zimmerman, and again in 1995, C. West and S. Fenstermaker, provided an excellent description of the "doing" of gender in two groundbreaking articles.14 The relevance of their ideas for understanding gender as part of a socially construed reality was confirmed in another article published in 2009.15 Their evaluation of the "gendered" society is most useful for investigating the nature of women's agency in the general activities of the OB. Doing gender is described as follows by West and Zimmerman:

The "doing" of gender is undertaken by women and men whose competence as members of society is hostage to its production. Doing gender involves a complex of socially guided perceptual, interactional, and micro-political activities that cast particular pursuits as expressions of masculine and feminine "natures". Gender is not a set of traits, nor a variable, nor a role, but the product of social doings of some sort.16

The definite separation between men and women in the OB shows that OB members' understanding of gender differences was to a great extent determined by the belief in the "essential nature" of men and women. The first document made public by the fathers of the OB, namely the goals of the OB, indicated the importance of gender as line of demarcation. The fifth point calls for "the inclusion and incorporation of all Afrikaners, men as well as women, who underwrite these goals and are willing to work vigorously toward these ends".17 Men and women differed "by nature" on the basis of biological criteria, that is, on the basis of a "determination made by the application of socially agreed upon biological criteria for classifying persons as females or males."18 However, the OB differed from most other movements in which women were involved in the sense that it was a movement for "men as well as women". In the Afrikaans Christian Women's Society (ACW)) and South African Women's Federation (SAVF) women took the lead and only women could be members - gender was a condition of membership.19 In the OB this was not the case and therefore it was considered particularly important to divide the activities of OB members along gender lines so as to preserve the gender order:

Insofar as a society is partitioned by "essential" differences between women and men and placement in a sex category is both relevant and enforced, doing gender is unavoidable. Doing gender means creating differences between girls and boys and women and men, differences that are not natural, essential, or biological. Once the differences have been constructed, they are used to reinforce the "essentialness" of gender.20

The construed differences between the genders come to the fore very distinctly in the activities of OB women during the period 1938 to 1943. The "essential nature of gender" was also emphasised in the Women's Auxiliary Council's (WAC) description of the duty of women in the OB. This specific description was derived by the women themselves: "that the women should inspire the men to service and devotion and should give moral support where necessary in order to comply with the objectives laid down in the OB constitution"21 It was implicitly accepted that women had the capacity to act as moral pillars for men, as auxiliaries who acted in a supporting role. Women also had to do diligent service in the OB but it was not deemed necessary for them to have someone giving them moral support. Thus women were constructed as the essence of service and dutifulness.

The differences between men and women were construed in such a way that women, through their activities, gave symbolic justification to the men's activities. Creating this objective made it almost impossible for the women's behaviour not to interact with that of the men. Gender was always constructed relationally. When the women worked hard in the OB it was seen as a call for the men to apply themselves to their duty. So, for instance, every now and then there were reports in the official OB newspaper, Die OB, about women who in their conduct served as an inspiration to action.

Mrs J.A. Smith,22 the spouse of the vice commandant-general, J.A. Smith, helped out several times in the OB friendship centre in Cape Town and her services were described as "an example of helpfulness which reflects the spirit in the Ossewa-Brandwag".23 OB women whose husbands had been arrested or interned24 often walked to the prison to sing national songs:

The conduct of these brave women reminds one of the days during the Second Anglo Boer War when the enthusiasm of women in the end made it almost impossible for the British to arrest the men in the Cape Province.25

About this type of incident Mrs J. Marais writes the following in her memoirs: "We wanted to give moral support to our men there in prison. And they did hear us. They say it was a great inspiration to them that we did it."26 Mrs H. van Eck promised £1 if the Stellenbosch commandos could raise £100. This acted as the inspiration for raising £111 and was described in Die OB under the caption "Needy mother sets example".27 The fact that these frequent reports on women's actions served as inspiration to the men, can be seen particularly well in a specific report on Mrs Ferguson-Louw who was described as a "well-known Afrikaans painter" who donated her paintings to be auctioned on Fundraising Day28 and "... in order to give the poorer members of the OB a chance as well, it had to be auctioned in shillings". By 1942 she had already sold six paintings and had raised £25 for the benefit of the OB and the hope was expressed "that this lovely example by an Afrikaner woman will also be followed by members of the male sex".29 Sometimes the calls made for Fundraising Day were definitely propagandist, clearly using singular interpretations of the volk:

If the mothers of the volk in the past were willing to sacrifice their sons, yes even their infants, on the altar of our freedom, are you not prepared to sacrifice just a small part of your income on the altar for the same freedom which has not yet been realised? You will be given this opportunity on 8 August.30

This symbolic presentation of women turned almost every action by them into a matter of gender, or a "gender action", since the smallest to the greatest deed had symbolic value - the ability to inspire men to service and devotion. However, Ob women had a unique view of their role and did not of necessity regard every deed as something primarily intended to support the men. A female OB general, A.C.M. Mostert, later chief woman of Area F, wrote:

During its development the Ossewa-Brandwag realised very well that where it found itself on the road of South African women, mothers and daughters had to join in their action. Therefore ample provision was made in the organisation for women. In this respect the Ossewa-Brandwag is unique. Although political and social organisations employed women as workers and helpers, we find that in the Ossewa-Brandwag women as an organised unit took part in all the activities of the movement. Women are not only there to hold functions, a "spare wheel" as it were, but are involved in the same way and with the same status as the men.31

The fact that some women regarded their position in the OB in this light shows that women's agency did not necessarily have to be manifested in formal politics in order for them to possess power. It is necessary to recognise that such power was severely compromised and constrained. Although their activities differed, women saw themselves as "having the same status as the men" which is open to critique. Therefore there were distinct differences in perspective on the position of women in the OB, but everywhere the symbolic character of women could be discerned. By way of the volksmoeder image, women were constructed as symbols of morality, the essence of morality that could not err morally but served to give moral direction. However, in contrast to Afrikaner women, Afrikaner men were seen to be more prone to err morally, as Mrs E. Holm of the OB justifiably put it:

The volk experiences what a boy does during the years that he develops into male maturity. He is not yet able to formulate the tender feelings awakening in him. Then he is overwhelmed by the cynical noise of jazz music and becomes entangled in the nets of a prostitute. This satisfies him more - and with something other than what he desires. It will take a long time before he will find the language of his own love - who knows, perhaps he will never find it.32

This metaphor expressed by Mrs Holm is an eloquent one. She uses the illustration to refer to the state of affairs in the Afrikaner volk of the 1930s and 40s. It refers in particular to the impact of urbanisation and the fear among nationalists that the urbanisation of the Afrikaner would lead to moral decline. The volksmoeder and her conservative image was inter alia a reaction to these fears. The volk could err morally but the volksmoeder was there to intervene - she was the source of morality who could rectify the situation: "Women intuitively feel the essence of these things, understand the drive of nature from their own structure."33 The latter reference to "nature" indicates that OB women themselves also partook in the construction of differences between men and women by emphasising and confirming the "essentiality" of their morality ("their own structure"): "As the women are, so will the volk also be! The feminine vocation and spirit must reign in all our activities, for then there will be hope for what is good in the life of our volk34 Notwithstanding the symbolic, inspirational nature of women's activities, "doing" gender surfaced in almost every activity of OB women.

Taking care of the dependents of the interned was one such activity assumed by women. The very reference to wives of the interned as "dependents", gives an indication of the influence gender had on the understanding of gender differences by contemporaries. As a social institution, gender awards certain social statuses to men and women in a particular society. By way of these statuses gender then becomes a justification for awarding certain rights and responsibilities to men and women.35 Although there was an identifiable group of working class women in Afrikaner circles, it was predominantly the men who in the 1940s were responsible for occupational labour on the basis of gender. His labour had to enable his wife to do the housekeeping and raise children and her labour in turn had to enable the husband to engage in his occupation without having to take part in the responsibilities of housekeeping. As a result of this gender order the internment of men was devastating for certain women who were completely dependent on the man's income. Instead of claiming that a change should take place in the gender order, for instance by encouraging women to seek employment, the women of the Ossewa-Brandwag, by means of their fundraising exercise, saw to it that the gender order was maintained by raising money for the OB Emergency Fund.36

Afrikaner women who went to work in the city were despised because according to their contemporaries such women did not assume the true role of an ideal volksmoeder:37 The volksmoeder image of the OB discouraged occupational labour by women as can be seen from the nature of the roles undertaken by the Women's Division; these were totally focused on housekeeping and motherhood. Internment was dealt with as something merely temporary - after the war the interned would once more be able to fulfil their gendered responsibilities. To enable their sisters not to forsake the ideal of the volksmoeder and to keep up their duties in the home, OB women construed the gender order through their endeavours to contribute to the Emergency Fund. While the economic situation was in fact a threat to the gender order, it was maintained by the OB. The active process of construction in which women took part emerges in particular in the responsibilities and rights awarded by gender as a process to OB women -in other words in their "doing gender" as sisters to the needy.

As members of the Ossewa-Brandwag men and women were also responsible for separate aspects of the care of "dependents". OB men could distribute farm produce and deliver this to families who were without a bread winner, but donations like clothes and shoes had to be managed exclusively by the local organisation of the OB Women's Division.38 In this respect the particular nature of women's position in the gender order gives a clue to why this was so. According to D.E. Smith, women's place in their particular sphere supposes the "immediate, local, and particular place in which we are in the body".39 Men could provide the raw products for food, products which he had cultivated, but the food had to be prepared by women themselves -because domesticity was their duty. Likewise men were prevented from infringing on the particular - bodily - world of women by allowing the donation of clothing. They assigned the duty of distributing clothes among women to other women. What is more, should a man have done the distribution, his help would have been construed as humiliating according to the gender order of the day.

The latter point was stated emphatically by the OB leadership in a circular to the effect that there should be "no atmosphere of humiliating charity".40 To prevent any such implication it was specifically OB women who had to give moral support to their "needy sisters". The OB laid down that "women have a particular bent for this duty", in other words, the duty of charity.41 In essence, carrying out the duty of charity involved certain gender deeds in such a way that there would be "no humiliating spirit of charity". When a needy family had been identified, a woman from the local OB women's commando paid her a visit in the form of a "true Boer visit" or an "outing to go along in the family car to the OB function, to some or other social entertainment, to the Zoo, or just out into the veld"42 - all of which were gender deeds. When two women arrived at an OB function, one a member of the commando and the other the wife of an interned, it would be accepted as "normal". However, if a man should arrive at a function with the wife of an interned, or walk with her alone "in the veld" or take her on an outing for a drive, eyebrows would undoubtedly be raised. In the words of West and Zimmerman:

It is individuals who "do" gender. But it is a situated doing, carried out in the virtual or real presence of others who are presumed to be oriented to its production. Rather than as a property of individuals, we conceive of gender as an emergent feature of social situations; both as an outcome of and a rationale for various social arrangements and as a means of legitimating one of the most fundamental divisions of society.43

Women were considered to have an exceptional bent for charity solely on the basis of their gender, since it was accepted as a matter of course that charity was for the most part the sphere of women. Thus J. Lorber writes:

Human society depends on a predictable division of labour ... one way of choosing people for the different tasks in society is on the basis of their talents, motivations, and competence - their demonstrated achievements. The other way is on the basis of gender - ascribed membership in a category of people.44

Whether individual women might be more talented to repair motor cars, or to farm, or that some men could be better housekeepers, was never even considered - biological essentialism determined the gender norms of contemporaries. The fact that gender is "one of the most fundamental divisions of society" also emerges from the absence of social mobility within the official ranks of the OB.

Officially, men and women were not supposed to infringe on one another's defined terrain. However, the gender order made the presence of men "essential". One of the best examples is the stipulation that Fundraising Day was exclusively the initiative of the women and that men had to support the women on that day and cooperate with them. It would seem as if on this day the gender tables were turned, however the presence of men confirms the power of the existing gender order. It was laid down that the initiative for organising the Fundraising Day would be left exclusively to the women, but that "the wholehearted support and cooperation of the men was essential".45 Men did have access to higher gender statuses in the OB and even though they could not take over the duties of the women they were present even in the supposedly feminine space of fundraising in that "the men had to exert themselves to assist the women in all respects as far as possible".46 Doing gender can further be observed in the specific nature of women's camps and other fundraising initiatives.

"Doing gender" should not be regarded as merely adhering to a list of prescribed aspects. Its nature is dynamic and changing. It was similar to the symbolic nature of the volksmoeder who played an integral part in the gender role of OB women. On the dynamics of gender deeds Lorber writes:

Members of a social group neither make up gender as they go along nor exactly replicate in rote fashion what was done before. In almost every encounter, human beings produce gender, behaving in the ways they learned were appropriate for their status, or resisting or rebelling against these norms.47

Although on occasion OB women overstepped and even altered gender norms,48 they never openly opposed the gender order of the movement. In this respect women's camps were an important part of OB women's gender deeds, because at these camps opportunities were provided for the education of women with the objective of having their conduct and activities conform to the normative concepts created by the volksmoeder. It was the "motherhood" and "domesticity" of women which received most attention during lectures and activities at the camps.49 Gender norms for the division of labour between the sexes were confirmed at the camps. For instance the demonstrations given were focused on skills such as dressmaking. Needlework was seen as one of the things a woman should do and demonstrations included making woollen buttons, sun hats, leather belts, spinning wool, etc.50 Apart from the various demonstrations, the lectures and speeches presented at the camps are another clue to the "gender deeds" for which the women were required to prepare themselves. Young girls as well as the older women attended lectures on "child care" and once again the role of a woman as a volksmoeder was stressed.

On occasion, talks were presented by men such as Dr Bührmann's on "The Influence of Women and Mothers on the Future of Children and the Volk". Women's influence as mothers in wider society was considered significant. For instance Dr Bührmann made the point that "our prisons, hospitals and mental institutions are full as a consequence of the questionable conduct of parents - especially mothers".51 The subject of the volksmoeder was specifically dealt with in these lectures, as can be seen from the extrapolation of the themes to apply to the volk in its entirety rather than just in the immediate family. Women were made responsible not only for the health of their own families but also indirectly for the health of their volk.52 The demonstrations and lectures thus served to educate women by laying down certain gender deeds which strengthened and confirmed their position in the gender order. By undertaking these deeds women filled their appropriate roles as volksmoeders in the Ossewa-Brandwag. An additional aspect of the volksmoeder highlighted by these gender deeds is that of the "caring" mother, a tendency that emerged more strongly after the reorganisation of the OB in 1943.53

Furthermore, the handmade articles produced by OB women was also closely linked to "doing gender". An excellent example of this was the so-called "apron evening". Each woman in the commando would make an apron and wear it to the OB function. The menfolk present at the function then threw coins into the pocket of the apron they liked the best and at the close of the evening the aprons were auctioned. Women already "did gender" by making the aprons and a unique social "folk dance" was performed when the aprons were auctioned. Again, men were cast in the mould of those who made the money and women as those who functioned in domestic matters. During the apron evening, gender deeds were acted out in that men demonstrated their capacity as bread winners by pouring the money, as it were, into the laps of the mothers. The woman's gender deed, namely making the apron (a specifically domestic item) was then rewarded in the form of money. The apron evening in itself supposes various gender deeds with women acting as the party who tried to win the favour of the men with their artistic products. Again, a gender deed like the abovementioned method of fundraising was not merely seen as a way of accumulating funds per se but was also coupled with the nationalistic ideals inherent in the OB volksmoeder. The WAC defined the objective of fundraising in nationalist terms. Fundraising had to ensure that "the enormous organisation of the OB could continue to mobilise the volk for the final charge".54 Another example of this was the call by a female general named Meyer to hold a Freedom Day55 celebration to raise a large amount of money; she saw fundraising as a form of resistance and an opportunity to gain a symbolic victory for the republic.56 In her view:

Just as in former days [when the republics were at war] when the women took on the task of casting bullets, thus guaranteeing the safety and survival of their men, so the women in the Ossewa-Brandwag will take care of the necessary funds so that the struggle can be continued and victory attained.57

Further ideological connotations of the volksmoeder were expressed in the OB's understanding of the "dress of the nation". OB women attached particular meaning to the white dresses they wore as uniforms. This meaning also flows from the OB's view of the "volksdrag" ("clothes of the nation") which was expressed very strongly during the centenary celebrations of the Great Trek. With the heightened nationalism of the centenary, a pride emerged among Afrikaners of things that were their "own", and in this way the dress of the Voortrekkers was elevated to a nationalist symbol. In an article on this theme, an OB woman expressed her view that the Voortrekker bonnet had become "an artistic creation as meaningful as any great national artistic achievement by a gifted individual". In this material cultural creation one finds an enormous number of symbolic meanings flowing from the ideological nature of the volksmoeder. Something particular, namely the Voortrekker bonnet of a "gifted individual", is elevated to a "national artistic achievement" with universal connotations, a symbol of women as proud mothers of their nation. The physical manifestation par excellence of the volksmoeder during the 1930s and 1940s was that of an Afrikaner woman in a Voortrekker dress and bonnet. Thus Mrs Kotie Roodt-Coetzee wrote: "the Voortrekker bonnet, especially the linen bonnet in light shades, is unique of its kind: it is truly something of the Boer!"58

The symbolic myths attached to the purity of Afrikaans women were directly linked to the bonnet as is evident in Roodt-Coetzee's choice of words: "The material was usually of a light shade; the bonnet itself was without unnecessary frills and bows; it was so much cleaner and purer in form than the brown and black bonnet."59 The bonnet represented the ideals of the volksmoeder in contrast to the bonnets worn by women in Europe, "the Voortrekker poke-bonnet presents as a cheerful but modest child, unpretentious and with nothing delicate about it, but redolent with unassuming beauty". The Voortrekker bonnet was abstracted to a metaphor representing the Afrikaner volk: "This bonnet personified the nature of the Trekker; it is a symbol of the spirit of the Trekkers." Just like the volksmoeder who represented the ideal for an individual woman and collectively for all Afrikaner women, the ornaments of the bonnet were also unique; these bonnets belonged exclusively to the volk. They held meaning for the Afrikaner community as a whole but also for the woman herself: "in the second instance it is also individual."60

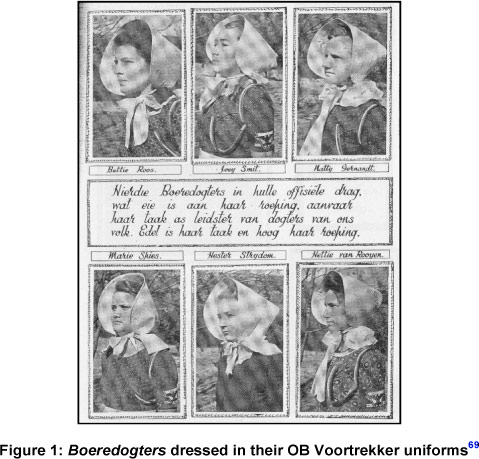

Although various aspects of Scott's conceptualisation of gender surface here, it is particularly clear that the bonnet was regarded as a culturally available symbol which represented the normative concepts of the volksmoeder as a gender ideal.61 This brings to mind certain symbolic images which are inherent in the nationalistic nature of the volksmoeder: The OB woman was regarded as pure, modest, cheerful, unpretentious, artistic with needle and yarn, unassuming and beautiful. These qualities were often converted to the normative concepts which maintain a gender order. In particular, it was the dress of the Boeredogters, "Boer girls" or, literally, "Boer daughters", who belonged to the youth wing of the OB, which call to mind the symbolic images as set out by Roodt-Coetzee. As a manifestation of the volksmoeder in the OB, the official dress of women was closely interwoven with the gender order of the movement ("her vocation ... her duty") and was filled with metaphoric meanings which either offered the possibility of using the construct as a motivation for more power, or as a construct to limit women's agency. As expressed in Figure 1 below, "Noble is her duty and exalted her vocation". Whether these metaphoric meanings work in a limiting or liberating way depends of course on the circumstances which either make room for women to take up their position as mothers of the volk (a political position) or not.

That the above was not only the opinion of an individual OB woman clearly transpires from the manifestation of the volksmoeder in the OB's official dress, not only the women in white dresses, but also the Voortrekker uniforms of the Boeredogters in Figure 1. The Boeredogters were under supervision of the women's division. It was stipulated that "the girl's division of the Youth Movement must fall under the Women's Division".62 In line with the way members and leaders of the OB understood gender differences, the activities of the official youth wing were also divided on the basis of gender. In other words, the activities of the Boerejeug were divided appropriately between the boys and girls. Some of the activities were similar but close examination of the OB's division of labour on the basis of gender shows that the activities were geared towards equipping the male and female genders for their respective duties.63

In an official OB pamphlet it was stipulated that it was "the duty of all true Afrikaner boys or girls to exert themselves and together oppose foreign class differences from impinging upon the life of the volk; they had to work towards true unity and the total freedom of the volk".64 Knowledge was very important to make sure that the youth would not forsake this duty. In this way, OB ideology was impressed upon both boys and girls while they were on OB camps, although matters concerning the politics of the volk took up a great part of lectures held for the boys. While boys were occupied with field work like direction-finding, compiling and reading maps, tracking, "tricks of attacking" such as quietly approaching the enemy, OB women paid particular attention to training Boeredogters in first aid and domestic matters.65

As a social institution the volksmoeder manifested itself specifically in the social context of the OB. In the words of Berger and Luckman: "... [gender] is socially controlled by its institutionalisation in the course of the particular history in question". The volksmoeder acted as an institution filled with gender norms and women's conduct was determined by, but also contributed to, the construct of the volksmoeder. The OB formed fertile soil for such a construct to flourish. "In actual experience, institutions generally manifest themselves in collectivities containing considerable numbers of people."66 Although women themselves took part in construing the volksmoeder, the social institution contributed greatly to maintaining the gender order. This was done by accepting women's "essence" or "essential ideal" as volksmoeders as something obvious. An example of this is seen in the OB's use of the volksmoeder rhetoric in a statement that the Boeredogters would fall under the guidance of the WAC: "It stands to reason that such education and moulding of the girls be entrusted to the women and mothers of the volk."67 This had far-reaching consequences for the maintenance of a gender order. J. Lorber refers to Bourdeu, Foucault and Gramsci when she mentions:

The gendered practices of everyday life reproduce a society's view of how women and men should act. Gendered social arrangements are justified by religion and cultural productions and backed by law, but the most powerful means of sustaining the moral hegemony of the dominant gender ideology is that the process is made invisible; any possible alternatives are virtually unthinkable.68

OB women construed their identity mainly within the discourse of the volksmoeder. In the construction of their identity OB women often made statements about their position in the organisation. As a summary of the nature of women's gender deeds in the common activities of the OB and of the nature and maintenance of the gender order, the following description of OB women's duty expressed by a woman leader is revealing:

The duty of women in the Ossewa-Brandwag is a taxing one. In many respects much is expected of her. No one ever has a life completely free of problems. Opposition and disappointments will always be part of it. Nevertheless the woman in the Ossewa-Brandwag faces up to all troubles and fills her humble position. She realises that the volk needs her services and she gives it in a committed and unselfish way. She has undertaken to come forward in these dark days and exert herself. She gives moral and practical support to her compatriots who sit helplessly between four walls. To their families who are equally helpless she offers her best advice and lends a helping hand everywhere. Yet she is neither smug nor sits back at ease, for there is still a long way to go.70

The volksmoeder was a useful tool for understanding how contemporaries saw gender differences and the meanings they attached to these differences. However, the volksmoeder was also a social construction that encompassed important gender norms and these were followed by OB women when they were "doing gender". The norms and ideals of the volksmoeder were intertwined with the doing of gender. As an institutionalised construction, the volksmoeder was not necessarily created by the women who exercised their agency within its constraints. As women, the members of the OB were constituted by a social world they did not necessarily choose. Their doing of gender was dependent on the norms of the day. It is here where we see the relation between the performativity of gender and the nature of the volksmoeder as a normative gender construction. In the words of Butler:

If I am someone who cannot be without doing, then the conditions of my doing are, in part, the conditions of my existence. If my doing is dependent on what is done to me or, rather, the ways in which I am done by norms, then the possibility of my persistence as an "I" depends upon my being able to do something with what is done to me.71

The last sentence is of particular interest. Women could also do something to the volksmoeder. As a construction full of culturally available symbols, rife with metaphorical possibilities, the volksmoeder could be reconstructed and moulded by women through giving meaning to their own identity as volksmoeders. Although the gender norms were dictated by the society of the day, women could change the way it operated. However, this does not mean they could be part of the OB and transgress the established norms. Their actions reinforced the volksmoeder, because even though there is a reciprocal relation between the normative and the performative, the following words by Butler still ring true:

This does not mean that I can remake the world so that I become its maker ... My agency does not consist in denying this condition of my constitution. If I have any agency, it is opened up by the fact that I am constituted by a social world I never chose.72

Almost every deed carried out by women in the OB was a gendered one. The reason for this is because women's role in the movement and in Afrikaner society at large was cast in extreme symbolic terms - as mothers of the nation, their deeds all contributed to the mothering of the volk. One example is the fact that women's actions were seen as an inspiration for the men - to make them loyal and dutiful by setting the example. In nothing that she did was it possible for women to escape this. However, women themselves did not see their deeds as a mere source of inspiration. They saw them as symbolic deeds of morality; and it would seem that the ideal was to become the essence of morality for the volk.

Women also used the rhetoric of biological essentialism to motivate their moral role. Thus, we see a biological determinist understanding of gender, normatively inherent in the volksmoeder and manifested in the deeds of women. Although women were actively involved in the discourse of the volksmoeder and the changing nature of identity-politics, they did not escape the confines of the volksmoeder as a normative concept. In the case of women's general activities in the OB we can agree with West and Zimmerman when they assert that "doing gender is unavoidable".73

1. N. Diederichs, Nasionalisme as Lewensbeskouing en sy Verhouding tot Internasionalisme (Nasionale Pers, Bloemfontein, 1936), p 59. Direct quotations from the primary sources have been translated into English throughout this article

2. Key works on the history of the Ossewa-Brandwag include the following: P.F. van der Schyff (red), Die Ossewa-Brandwag: Vuurtjie in Droë Gras (PU vir CHO, Potchefstroom, 1991); P.J. Furlong, Between Crown and Swastika: The Impact of the Radical Right on the Afrikaner Nationalist Movement in the Fascist Era (Witwatersrand University Press, Johannesburg, 1991); C. Marx, "The Ossewabrandwag as a Mass Movement, 1939-1941", Journal of Southern African Studies, 20, 2, June 1994, pp 195-219; C. Marx, Oxwagon Sentinel: Radical Afrikaner Nationalism and the History of the Ossewa-Brandwag (Unisa Press, Pretoria, 2008).

3. The role of the volksmoeder in the Voortrekker centenary celebrations and in the OB are discussed in the following works: M. du Toit, "Framing Volksmoeders: The Politics of Female Afrikaner Nationalists, 1904-c.1930", in P. Bacchetta and M. Power (eds), Rightwing Women: From Conservatives to Extremists around the World (Routledge, London, 2002), pp 57-70; A. McClintock, Imperial Leather (Routledge, London, 1995); A. McClintock, "No Longer in a Future Heaven: Women and Nationalism in South Africa", Transition, 51, 1991, pp 104-123; C. Blignaut, "Volksmoeders in die Kollig: 'n Histories-teoretiese Verkenning van die Rol van Vroue in die Ossewa-Brandwag, 1938-1954", MA dissertation, North-West University, 2012.

4. L. Vincent, "The Power behind the Scenes: The Afrikaner Nationalist Women's Parties, 1915-1931", South African Historical Journal, 40, 1999, p 64.

5. E. Brink, "The Afrikaner Women of the Garment Workers' Union, 1918-1939", MA dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, 1986, p 280.

6. J. Butler, Undoing Gender (Routledge, New York, 2004), pp 1-2.

7. J.W. Scott, "Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis", American Historical Review, 91, 5, December 1986, p 1069. The importance of Scott's work for the field of gender history cannot be exaggerated. The fundamental argument in her most important article, namely, "Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis", is still relevant today which can be seen in the trajectory of her thinking from 1986 to 2011. See for example, J.W. Scott, Gender and the Politics of History (Columbia University Press, New York, 1988); J.W. Scott, Gender and the Politics of History (Columbia University Press, New York, 1999); J.W. Scott, "Millenial Fantasies: The Future of 'Gender' in the 21st century", in C. Honegger and C. Arni (eds), Gender: Die Tücken einer Kategorie (Chronos, Zurich, 2001); J.W. Scott, "Unanswered Questions", contribution to AHR Forum, "Revisiting Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis", American Historical Review, 113, 5, December 2008, pp 1422-30; J.W. Scott, "Gender: Still a Useful Category of Analysis?", Diogenes, 57, 225, February 2010, pp 7-14; and J.W. Scott, The Fantasy of Feminist History (Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2011).

8. Scott defines "gender" as an integral connection between two propositions when she writes that gender is a constitutive element of social relationships based on perceived differences between the sexes, and that gender is a primary way of signifying relationships of power. See Scott, "Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis", pp 1067-1071 for a detailed exposition of her definition.

9. Scott, "Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis", p 1067.

10. This rich, meaning-imbibed nature of gender phenomena is not unique. Scott mentions that the elements of gender are interrelated and therefore culturally available symbols and normative concepts cannot necessarily be demarcated.

11. For what is meant by "acting in concert", see Butler, Undoing Gender, pp 1-16.

12. It is important to take into account that not all women are the same and not all Afrikaner women experienced gender constructions in the same way. This article looks specifically at a number of women who belonged to an organisation with a very circumscribed gender order.

13. From 1943 the emphasis of the activities of the Women's Division changed after the reorganisation of the OB in 1942.

14. C. West and D.H. Zimmerman, "Doing Gender", Gender & Society, 1, 2, 1987, pp 125-155; C. West and S. Fenstermaker, "Doing Difference", Gender & Society, 9, 1, 1995, pp 8-37.

15. C. West and D.H. Zimmerman, "Accounting for Doing Gender", Gender & Society, 23, 1, 2009, pp 112-122. [ Links ]

16. West and Zimmerman, "Doing Gender", pp 126, 129.

17. A.J.H. van der Walt, 'n Volk op Trek: 'n Kort Geskiedenis van die Ontstaan en Ontwikkeling van die Ossewa-Brandwag (Kultuur en Voorligtingsdiens van die Ossewa-Brandwag, Johannesburg, 1941), pp 12-13.

18. West and Zimmerman, "Doing Gender", p 126.

19. See in this regard, B.Y. Eisenberg, "Gender, Class and Afrikaner Nationalism: The South African Vrouefederasie", BA Honours essay, University of Witwatersrand, 1987; and M. du Toit, "Women, Welfare and the Nurturing of Afrikaner Nationalism: A Social History of the Afrikaanse Christelike Vroue Vereniging", PhD thesis, University of Cape Town, 1996.

20. West and Zimmerman, "Doing Gender", pp 136-137.

21. Ossewa-Brandwag Archives, Ferdinand Postma Library of the Potchefstroom Campus of North-West University (hereafter OBA): Vrystaatse Beheerraad-versameling (vers.), B/L 6/1, omslag 2: Bevel no. 5/42, aanhangsel A.

22. For the purpose of this article the gendered prefix "Mrs" is used because contemporaries referred to themselves as such.

23. OBA: Die OB, 28 February1942.

24. Under the emergency regulations declared by the Smuts government at the time, any individual suspected of being a threat or potential threat to the war effort could be interned without trial. Because of the OB's pro-German stance, thousands of OB members were interned or arrested.

25. OBA: Die OB, 4 March 1942.

26. OBA: Tape recordings, transcription (tr.), tape no. 208, 1985: Memories of Mrs J. Marais, p 3.

27. OBA: Die OB, 18 December 1942.

28. Also called "Ossewa-Brandwag Day", this was the main fundraising event organised annually by the Women's Division and took place on 8 August. It celebrated the "birthday" of the OB, or at least the idea of the OB, in 1938.

29. OBA: Die OB, 13 May 1942.

30. OBA: Die OB, 22 July 1942.

31. OBA: A.C.M. Mostert, "Die Vrou in die Ossewabrandwag", in OB Jaarboek 1948, p 13.

32. OBA: E. Holm, "Vir die OB Vrou: Die Vrou en die Kuns", in OB Jaarboek 1948, p 24.

33. OBA: Holm, "Vir die OB Vrou", p 24.

34. OBA: B.C. Seymore, "Die Vrou in die Ossewabrandwag", in OB Jaarboek 1947, p 28.

35. J. Lorber, '"Night to His Day': The Social Construction of Gender", in P.S. Rothenburg (ed), Race, Class and Gender in the United States: An Integrated Study (Worth Publishers, New York, 2006), pp 54-65. See also Scott, Gender and the Politics of History, pp 43-44.

36. The Emergency Fund was set up by the OB to help the families of men who were interned.

37. See in this regard E. Brink, "Maar net 'n Klomp 'Factory Meide': Afrikaner Family and Community on the Witwatersrand during the 1920s", in B. Bozzoli (ed.), Class, Community and Conflict: South African Perspectives (Ravan Press, Johannesburg, 1981); and L. Vincent, "Bread and Honour: White Working Class Women and Afrikaner Nationalism in the 1930s", Journal of Southern African Studies, 26, 1, March 2000, pp 61-18.

38. OBA: G. Cronje-vers., B/L 1/12, omslag 1: Die OB Noodhulpfonds.

39. D.E. Smith, "The Conceptual Practices of Power", in C. Calhoun, J. Gerteis, J. Moody, S. Pfaff and I. Virk (eds), Contemporary Sociological Theory (Blackwell, Oxford, 2001), p 311.

40. OBA: P.J. Meyer-vers., B/L 1/4, omslag 4, OB Noodhulpfonds: Memorandum.

41. OBA: G. Cronje-vers., B/L 1/12, omslag 1: Die OB Noodhulpfonds.

42. OBA: P.J. Meyer-vers., B/L 1/4, omslag 4, OB Noodhulpfonds: Memorandum.

43. West and Zimmerman, "Doing Gender," pp 126, 129.

44. Smith, "The Conceptual Practices of Power", p 55.

45. OBA: Transvaalse Beheerraad-vers., B/L 8(i)/1, omslag 1: Fondsdag, 8 Augustus.

46. OBA: Transvaalse Beheerraad-vers., B/L 8(i)/1, omslag 1 Fondsdag, 8 Augustus.

47. J. Lorber, as quoted by Smith, "The Conceptual Practices of Power", p 60.

48. See in this regard C. Blignaut, '"Goddank dis Hoogverraad en nie Laagverraad nie!': Die Rol van Vroue in die Ossewa-Brandwag se Verset teen Suid-Afrika se Deelname aan die Tweede Wêreldoorlog", Historia, 57, 2, 2012, pp 68-103.

49. OBA: Gebied C-vers., B/L 6/5/28: Omsendbrief 1/47.

50. OBA: Gebied C-vers., B/L 6/5/28: Omsendbrief, 29 November 1944: Vrouekamp.

51. OBA: Transvaalse Beheerraad-vers., B/L 8(i)/1/2: Toespraak: V. Bührmann, "Invloed van Vrou en Moeder op Toekoms van die Kind en Volk", 17 Augustus.1942.

52. OBA: Die OB, 14 April 1943.

53. Blignaut, "Volksmoeders in die Kollig", pp 238-298.

54. OBA: Vrystaatse Beheerraad-vers., B/L 6/1 omslag 2: Bevel no. 5/42, aanhangsel A.

55. Freedom Day was celebrated on 27 February - the date when the Boers were victorious over the British in 1881 at Majuba.

56. OBA: Gebied C-vers., B/L 6/5/28: Oproep: Vryheidsdagviering, 10 Februarie.1947.

57. OBA: Vrystaatse Beheerraadvers., B/L 6/2, omslag 6, Werkskema.

58. OBA: K. Roodt-Coetzee, "Gedagtes oor Ons Volksdrag", in OB Jaarboek, 1948, p 50.

59. OBA: Roodt-Coetzee, "Gedagtes oor Ons Volksdrag", p 52.

60. OBA: Roodt-Coetzee, "Gedagtes oor Ons Volksdrag", p 54.

61. Scott, Gender and the Politics of History, p 43.

62. OBA: J.S. de Vos-vers., B/L 1/8, omslag 8: Die Taak van die Vrou in die Volksbeweging.

63. C. Blignaut, and K. du Pisani, "Om die Fakkel Verder te Dra: Die Rol van die Jeugvleuel van die Ossewa-Brandwag, 1939-1952", Historia, 54, 2, 2009, p 146.

64. OBA: Boerejeug-vers., B/L 9/1, omslag 8: Boerejeugpamflette, "Die Boerejeug".

65. OBA: Boerejeug-vers., B/L 9/1, omslag 6: Uniforms, kleredrag, kentekens: "Erkenningstekens van die Boerejeug", 1948.

66. P.L. Berger and T. Luckmann, The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge (Random House, New York, 1967), p 43.

67. OBA: J.S. de Vos-vers., B/L 1/8, omslag 8: Die Taak van die Vrou in die Volksbeweging.

68. Lorber, "'Night to his day'", p 58.

69. OBA, OB Year Book 1948, p 51. The text reads: "These Boer girls in their official dress ... accept their duty as leaders of the girls of our volk. Noble is their duty and exalted their vocation."

70. OBA: Seymore, "Die Vrou in die Ossewabrandwag", p 28.

71. Butler, Undoing Gender, p 3.

72. Butler, Undoing Gender, p 3.

73. West and Zimmerman, "Doing Gender", p 136.