Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.37 n.3 Pretoria Aug. 2017

https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v37n3a1377

Using metaphoric body-mapping to encourage reflection on the developing identity of pre-service teachers

Carolina S Botha

School of Education Studies, Faculty of Education Sciences, North West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa. carolina.botha@nwu.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article explores the contribution that a teaching strategy, such as metaphoric body-mapping, can make towards the discourse on the development of professional teacher identity. Second-year students in a Life Orientation methodology module in a B.Ed programme were offered the opportunity to validate their local knowledge and make new meaning together, through bringing their lived experiences into the classroom. In a contact session, groups were tasked with using body-mapping to conceptualise metaphoric superhero and villain characters of both effective and ineffective teachers. In a subsequent discourse, the characteristics of these metaphoric characters were explored to set the stage for inter- and intrapersonal reflection on students' own social construction of their developing professional identities. This student experience clearly indicates that metaphors can be a rich and stimulating way for prospective teachers to talk about their perceptions, experiences and expectations of teaching, and the method accentuates the importance of tertiary institutions that contribute to the emerging conversation about the development of professional identity in pre-service teachers. This article pioneers the use of body-mapping as a group-based technique, where a group of people works together on the same body-map, rather than the traditional individual approach to this method.

Keywords: body-mapping; Life Orientation; metaphor; pre-service teacher; professional identity; reflection

Introduction

In 1938 cultural theorist, Johan Huizinga, coined the phrase homo ludens, which translates literally as 'the playing human' (Huizinga, 1938). He proposed the notion of learning through play and accentuated the value of play in self-discovery. This article explores the contribution that teaching strategies employing play through what the author regards as metaphoric body-mapping in a Life Orientationi methodology module, in a pre-graduate programme for second-year students, can have on interpersonal and intrapersonal reflection, along with meaning-making.

De Jager, Tewson, Ludlow and Boydell (2016) defined a body-map as a life-sized figure that is created by tracing the outline of a person that is subsequently decorated, drawn on or labelled. After this creative process, the visual content and meaning that have been made throughout the process are analysed through a reflective, narrative process. In this manner, body-mapping can also be used as a research method (Gastaldo, Magalhães, Carrasco & Davy, 2012), because participants' attention is drawn to both their physical bodies, as well as to an awareness and reflection on the experience.

Two contact sessions making use of the principles of body-mapping created opportunities for students to bring real-life experiences into the classroom. A hermeneutic approach acted as a vessel by means of which students are enabled to tap into their local knowledge and make new meaning together, before applying that new knowledge to their own personal development and identity formation. This article pioneers the use of body-mapping as a group-based technique, where a group of people works together on the same body-map, rather than the traditional individual approach to this method.

The Participants

This project was undertaken by a Life Orientation class with 75 intermediate phase second-year students, who were enrolled in the B.Ed programme at the North West University (Potchefstroom campus) in South Africa. This methodology module comprised of twelve weekly, two-hour long contact sessions, and addressed both the theory and pedagogy of Life Orientation, as well as the praxis of teaching, with a focus on curriculum interpretation and lesson planning, assessment and general methodology of teaching.

After returning from their first Work Integrated Learning experience,ii students expressed the need to discuss the challenges that Life Orientation as a subject, and committed Life Orientation teachers as individuals, were facing in the current South African educational landscape. This conversation naturally evolved to a discussion about the identity and work ethic of a good teacher. The project assessed in this article was born from that discourse. As a lecturer, the researcher knew that she wanted to engage students in more than just an oral or written discussion on the topic, and decided to explore the possibility of using a creative approach to further address the issue.

Before attempting to explore the concept of teacher identity with the students, one should have a clear understanding of the process of identity formation in pre-service teachers. In this research, the researcher came across the expression "apprenticeship of observation", coined by Lortie in 1975. This proved a suitable philosophical starting point for planning this project.

Teacher Identity

The apprenticeship of observation

Upon registering at a tertiary institution for their first year of teacher training in the B.Ed pro-gramme, students have already unwittingly obtained an "apprenticeship of observation" from their twelve years of schooling. Dan Lortie coined this phrase in 1975, explaining that students enter teaching programmes with pre-set ideas on the characteristics of a good teacher, conceptualised throughout their twelve years of schooling (Lortie, 1975).

In his seminal work on the teacher, Lortie (1975) described the pre-service teacher as bringing to the business of becoming a teacher a history that informs their beliefs about teaching and the work of teachers. Personal life history, as well as ex-periences of schools and teaching, is what pre-service teachers bring with them to teacher preparation programmes, affecting the way they manage the process of "becoming."

Students' identity has thus been constructed around what they consider teaching to be about. Their academic careers will subject students to a deconstruction of this preferred identity, when they are exposed to the curriculum content of especially methodology modules, as well as their experiences during Work Integrated Learning. Students might now start to question their identity, and deconstruct and critically examine discourses pertinent to their ideas of being a good and effective teacher. Much emphasis is being placed on guiding pre-service teachers towards developing and exploring their professional and personal identities, and this article aims to contribute to that conversation on a local and global level.

A social construction of teacher identity

Within a social construction paradigm, people and societies construct the lenses by means of which they interpret the world, that is, the beliefs, practices, words and experiences that make up their lives and constitute their selves (Botha, 2012).

Social constructivist discourse, therefore, is a theoretical paradigm that fundamentally rejects the viewpoint that identity is essential, biological and determined by historical factors. Rather, a social constructivist approach postulates that it is through language, interaction and practice that identities are ascertained (Burr, 2003). Identity is not a fixed attribute, but rather a relational and contextual phenomenon, where people need to constantly question their beliefs about events that have shaped the stories of their personal and professional lives (Taylor, 2017). Social construction discourse implies that no single story can ever sum up all the different meanings that people attribute to their lives and, in this way, the perception of all knowledge remains an interpretation.

Accepting the title of "teacher" can, therefore, be considered a "socially bestowed identity" (Burr, 1995:30), rather than the essence of a person, who happens to teach for a living. Flores and Day (2006:220) captured the essence of teacher identity as "an ongoing and dynamic process which entails the making sense and (re)interpretation of one's own values and experiences", that may be in-fluenced by personal, social and cognitive factors.

Earlier work on professional lives of teachers (Zeichner & Liston, 1996) and their personal and professional narratives (Connelly & Clandinin, 1999) validated the importance of research, paying attention to the further development of teacher identities. Beauchamp and Thomas (2009) provided an overview of issues related to teacher identity research that have arisen since the 1980s. Issues such as problems with identifying identity itself, the role of the self in professional lives, personal agency, emotion, narratives and self-reflection are mentioned. Palmer (2007) stressed the importance of teachers knowing themselves, as they con-ceptualise the beliefs, values and commitments that allow them to identify both as a teacher (pro-fessional identity) and as being a particular type of teacher (personal identity).

Teacher identity, therefore, encompasses not only notions of "who I am", but also of "who I am as a teacher" (Thomas & Beauchamp, 2011:763). This necessitates the thinking about identity on a personal, as well as a professional level. Identity is thus a key factor in a teacher's sense of purpose, self-efficacy, motivation, commitment and job satisfaction. Such an identity is constructed and negotiated within a social environment, and in response to multiple discourses about teaching. In teacher education opportunities need to be created as a means of framing and defining experiences and local knowledge in order to achieve meaning in one's life.

However, it is not always easy to describe one's identity when asked to do so. Allowing teachers the opportunity to step back out of everyday language, into the poetic language of metaphors, or to use other multimodal approaches to creating knowledge, can allow people to be descriptive and inquisitive about their developing identities in alternative, creative and sometimes highly effective ways (Brett-MacLean, 2009).

With this framework in mind, I searched for a suitable approach to activate the homo ludens in my students, tapped into their existing knowledge and apprenticeship of observation about the identity of teachers, and promoted reflective and critical thinking about their own praxis as teachers in training. The technique of body-mapping, as used in art therapy, seemed a perfect fit for the needs of this project.

Body-Mapping as Research Tool

Body-mapping originated in Jamaica, where Mac-Cormack and Draper (1987, cited in De Jager et al., 2016) utilised the technique to address reproductive issues in women. Use of the whole body for body-mapping was developed later in South Africa as an art-therapy method (De Jager et al., 2016). This technique was used for creating awareness and reflecting living with HIV/AIDS through a narrative process (Solomon, 2007). Body-mapping has since evolved as a feasible research method that generates rich visual and oral qualitative data. This method is frequently utilised for research on the understanding of gender role differences (Gastaldo et al., 2012), educating nursing students on teaching about HIV/AIDS (Maina, Sutankayo, Chorney & Caine, 2014), and creating awareness in the context of occupational health and safety. This method has also successfully been implemented in research in education, with specific reference to life design and career guidance (Ebersöhn, 2015), and pre-service teachers (Griffin, 2014).

In body-mapping, arts-based techniques, such as drawing or painting, are used to visually represent aspects of people's lives, their bodies and the social, political and economic world in which they live (Martinez & Nolte-Yupari, 2015). This enables participants to share and attribute meaning to their life stories, and investigate ways in which stories might be related.

The purpose of using body mapping in our study was to engage participants in a critical examination of the meaning of their unique experiences, which could not simply be achieved through talking; drawing symbols and selecting images helped them to tell a story and at the same time challenged them to search for meanings that represented who they had become (Gastaldo et al., 2012:8).

Art-based models of learning, such as body-mapping, are often used as part of teaching and learning due to the possibilities for transformation, conversation and creating new knowledge on com-plex issues. A platform is created where communal knowledge can be shared and dominant discourses deconstructed within a shared safe space.

Using art, specifically drawing, in research on teacher identity is not a new concept. The work of Theron, Mitchell, Smith and Stuart (2011) demonstrated that the inner world can be revealed by using drawing as a method, instead of only rely-ing on interviews, questionnaires or focus groups. Beltman, Glass, Dinham, Chalk and Nguyen (2015), as well as Freer and Bennett (2012), had also been instrumental in using drawings to research pre-service teacher identity. Results from both studies suggest that the examination of drawings of pre-service teachers may provide a feasible way forward in understanding the reality of the work of teachers. In their work, a multi-coloured, multi-sensory and multi-dimensional reality was created, where there was a constant interactive movement between verbal-visual, visual-verbal and visual-spatial modes.

The practice of body-mapping applies the same principles and, therefore, seems to be a useful tool for teaching and learning in a Life Orientation methodology module, to address the issues raised by students after their Work Integrated Learning experience. In this manner, body-mapping provides a suitable platform for critical reflection on the beliefs, expectations and development of teacher identity.

In the original facilitator's guide to body-mapping, Solomon (2007) suggested five full days or thirty hours for completing the three steps of body-mapping. Firstly, a group discussion is staged, where participants can share experiences and start brainstorming ideas. Then individual body-maps are created and a key for each body-map is made. The key provides an outline of the intention of the symbols and metaphors included on the body-map. An individual narrative - defined by Gastaldo et al. (2012) as a testimonio - is written or presented orally to explain the body-map and clarify the key (Gastaldo et al., 2012; Maina et al., 2014). Because the project unpacked in this article was part of the teaching and learning of a Life Orientation methodology module, and the activity would be considered as part of the formal formative assessment plan for the semester, time was a critical consideration. In the semester plan, only four hours (two contact sessions) could be allocated to the activity. I soon realised that I was obliged to adapt - but not modify - the original methodology of body-mapping to achieve the maximum effect with the exercise.

Although body-mapping is often presented as an individual activity, I decided to adapt the process to a three-phased activity that included a cooperative learning experience, as well as individual reflection activities.

During the first phase, the body-maps would be created as a group activity that could lead to students learning from one another, as well as reflecting on their own work. By comparing their experiences and their conceptualisations of teacher identity in the second phase, they could build stronger connections and form a community of ideas, where they could then further reflect on their own perceptions, ideas and actions.

The process enables participants to identify non-salient stories that shape their experiences, stories that are often invisible and unacknowledged. Body mapping enables participants to mark, identify and acknowledge these invisible stories and to attach meanings to them. To acknowledge the self and to be aware of one's identity is the ultimate achieve-ment (Maina et al., 2014).

It was also necessary to keep in mind that not all students would work at the same tempo, and process the information, on an intellectual and emotional level, or at the same rate. Some students might need more time to successfully accomplish these goals of the body-mapping endeavour than others. The decision was, therefore, made to add the third phase - an individual component - to the project where, after the groups had completed the body-map assignment, each student could then, in his or her own time, reflect on the process of body-mapping and apply the results of the group activity on an individual level. This created the space for the student who had not worked or processed information so fast, to not be constricted by the four-hour time limit of the project.

Using Metaphors as an Additional Vehicle for Reflection

While adapting the original concept of body-mapping, the researcher realised that using a metaphor to guide students in the structured group activity, might prove helpful and save time. Eren and Tekinarslan (2013:435) viewed metaphors as "crucial structures of the human mind" and defined them as "mental structures reflecting individuals' self-related beliefs, emotions and thoughts by means of which they understand and act within their worlds." Patchen and Crawford (2011:287) added to this by describing metaphors as "the compasses of our consciousness, the dynamic divining rods that show us what we need to see, when we need to see it." A metaphor is, according to Midgley and Trimmer (2013), not only a figure of speech, but rather constitutes an essential mechanism of the mind, and allows the modelling and reification of prior experiences. A metaphor can hence be understood as a vehicle to model experience and foster reflection that can lead to new insight and personal and professional growth (Buchanan, 2015).

Encouraging teachers to use metaphors to conceptualise their ideas of teaching and identity, as well as learning, can offer valuable insights into what they see as important, essential or harmful to their work. The metaphors that pre-service teachers use to represent professional thinking, were explored in several significant studies, including research executed by Saban, Kocbeker and Saban (2007) and Shaw and Mahlios (2008). These studies concurred that using metaphors can serve as a healthy reflective practice for teachers, as well as pre-service teachers.

Boud and Hager (2012) counselled, however, that the elicitation of metaphors does not necessarily ensure deep reflection. Another po-tential rift is that pre-service teachers might opt for choosing flourishing metaphors for themselves, rather than realistic representations of their sit-uations. Goldstein (2005) and Mahlios, Massengill-Shaw and Barry (2010), also pointed to the difficulties that pre-service teachers may have in construction of metaphors on their own, and suggested providing a sample of selection of metaphors to choose from.

Mindful of the warning, the decision was made to require students to conceptualise either a character displaying attributes of proper and effective teaching (a superhero teacher), or the opposite character, evident of ineffective and dys-functional teaching (a villain teacher). By accentuating the dichotomy, students would be exposed to both the attributes and identity of a good teacher, as well as be made aware of the behaviour of an unsuccessful teacher. By con-ceptualising one negative metaphor, students were prevented from only selecting positive metaphors that would not promote critical reflection on their own identities as teachers.

The Project

The project with second year pre-service teachers was structured into three phases. The first group phase took place in a large hall, while the second and third phases took part in the regular lecture hall for this module (refer to Table 1).

Preparation

Before attempting a body-mapping activity, it is important that meticulous planning goes into the preparation and set-up of the activity. The paper on which the body-maps are going to be drawn should be large enough for the participants to fit in their whole body (De Jager et al., 2016; Gastaldo et al., 2012; Griffin, 2014; Solomon, 2007). Extra paper can be made available, should groups want to add writing at the top or the bottom of the page. A wide variety of crafting materials should be made available to ensure that the participants are not limited and can be as traditional, or as creative as they wish (Solomon, 2007).

The size of the room in which the activity is going to be conducted, is also an important con-sideration. The exercise requires there to be enough space for participants to lie down and complete the body outline, as well as enough room for group members to walk around their creations while working. Body-mapping can easily be done on the floor, should enough space on tables seem prob-lematic.

Body-mapping a metaphoric character

Upon entering the hall at the beginning of the lesson, students randomly received a coloured card, with the letter A or B printed on the card. They were then instructed to locate six other individuals with cards of the same colour and letter that they had. The groups for the activity were then assembled. Five groups of students with the letter A printed on their cards were tasked with conceptualising and creating a body-map of a superhero teacher, while the four B-groups were responsible for designing and creating villain teachers. In this manner, groups were not merely made up of friends choosing to work together, but compiled of a variety of students of different backgrounds, racial groups, gender, and language preference.

The superhero group was to contemplate the characteristics of an excellent teacher, namely the kind of teacher who truly made a difference in the lives of their learners; someone who was sensitive, aware and respectful, and who strived towards being an agent of change in his or her classroom and school. Such a teacher would also be focused on promoting diversity and inclusivity in his or her classroom and school. The students' task was to assign such attributes to each of their body-maps by, for example, using the anatomy and fun-ctionality of the human body as a frame of reference. Students could, for example, wish to depict that their superhero stood firm in the values by which he lived (referring to his/her feet), or, that he/she was always sensitive for opportunities to help someone (referring to his/her eyes). In this manner, many internal and external parts of the human body could be used to indicate the per-sonality and behaviour of their superhero.

The groups tasked with designing a villain teacher (B-groups) had to do the same, but focused on the attributes they thought a very ineffective and dysfunctional teacher would display. They could, for example, decide that they would do the opposite than a great teacher, and be insensitive, oblivious and disrespectful. Such a person would not promote diversity and inclusivity in his or her classroom and school. In the vernacular, both superheroes and villains are recognised and characterised by their appearance and their names. Their identity is, therefore, closely linked to their physical appear-ance, and very often their names are descriptive of their behaviour. Because this activity was built upon the premise of humo ludens (Huizinga, 1938), and the idea of attaching identity to their characters was crucial to the overall aims of the activity, students were tasked to decide upon a name and distinctive outfit for their character.

Each group was provided with six sheets of flip chart paper, that they could stick together in any manner they chose to, after which they had to draw the outline of the body of one of the members of their group as a template for the design of their superhero or villain. It was made clear that, although important, the design of the character was not the main aim of the activity, rather the content written on the body-map, constituted the true focus of the engagement. Each group had to write down all the characteristics they bestowed upon their superhero or villain next to the relevant body part on their sheet of paper. They also had to decide whether that characteristic was an expression of a pedagogical or methodological part of a teacher's praxis, and indicate that on a separate table at the bottom of their design.

Groups were issued with basic stationary, such as coloured markers, scissors and glue. A communal table, with other purposive and even repurposed materials, such as coloured sheets, crinkle paper, wrapping paper, newspaper, and even balloons, was supplied for all groups to use. Students soon showed initiative and foraged some of their own materials - toilet paper, leaves and even soil proved to be popular choices.

Group dynamics of body-mapping

It soon became evident that no two groups were following the same process in designing their superhero or villain. Some groups chose to first brainstorm the attributes their character would have and then go on to the designing process. Other groups jumped right in and started the design; then, while they were drawing a face and designing an outfit, they discussed the written part of their assignment. It was interesting to see how the aesthetic part of the process seemed to be much more important to some groups than it was to others. Group dynamics were also quite distinctive and different. Some groups spent a considerable amount of time planning and creating a draft concept of their creation, while other groups simply relied on an organic and natural process of design that evolved as they progressed. In some groups, one student immediately took on the role as leader, while other groups were more democratic in division of the labour and in deciding upon the look and feel of their character. In another group, one member immediately took out a mobile phone on which to play some music while they were working, while another group handed out tasks and did not engage with one another, while they were working.

In other groups, passionate discourse ensued about certain characteristics, which some con-sidered to be extremely important and others might not have ranked so high on the scale of effectiveness of a good teacher. It was evident that this body-mapping assignment promoted ex-pression of local knowledge and the making of meaning in multiple forms for all the students involved. The open-endedness of the body-mapping assignment encouraged creativity and exploration of a variety of themes and ideas.

Meet the characters

The body-maps displayed a variety of character-istics of both efficient and dysfunctional teachers, represented as either a superhero or a villain. Figure 1 depicts a superhero teacher, called Dr Grow ("Dr. Groei"). He is concerned about the environment (as symbolised by the leaves from which his cape is constructed) and he is proudly emblazoned across his chest with the acronym LO, evidencing his passion for the subject of Life Orientation. His muscular appearance reflects his commitment to hard work and his willingness to walk the extra mile for his learners. His feet reflect standing steadfast on his values, and indicate the ability of an effective teacher to 'think on his feet.'

Firestarter, as depicted in Figure 2, is also a superhero teacher, who sparks a flame of passion in her students. She does not have a face, as she plays many roles, including those of teacher, mother, psychologist and friend. She offers her learners a shoulder to cry on and her elbows are indicative of a good teacher being flexible, rather than rigid and fixed. Firestarter also has a big heart, which is indicative of her being inclusive, emphatic and sensitive towards diversity and differences in her learners.

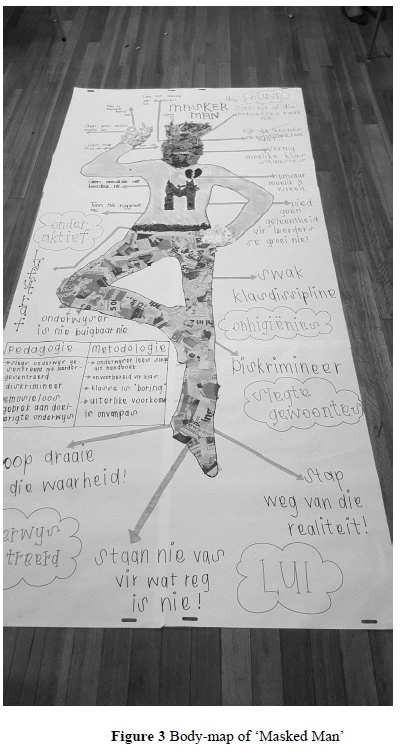

On the other hand, Figure 3 depicts a villain called The Masked Man ("Maskerman"), who wears many masks and does not show his true colours. He does not have eyes, which is indicative of the fact that he is not always aware of the needs of his learners. The Masked Man also has a distinctive broken heart, in recognition of the fact that his own hurt might make it difficult for him to accept all people, and leads him to be cruel, discriminatory and unkind. He does not stand on firm ground, as he cannot take a stand, and that leads to difficulty in maintaining good classroom discipline.

Miss Park (Figure 4) could possibly have made the wrong career choice, and is now taking it out on her learners. Her only teaching strategy is to read from a textbook. She is racist and unethical, uses foul language, engages in inappropriate relationships with learners, and partakes in behav-iour that is not acceptable. The large knife in her hand indicates the easy way she betrays colleagues, and stabs people in the back.

Summary

Although much fun was experienced during the two hours in which characters were designed, and a certain amount of reflection and discussion was facilitated, the metaphors possibly did not show enough evidence of the potential complexities or challenges of teaching (Beltman et al., 2015:225). The time limit on the activity and the content of the body-maps did not allow deep explorations on an individual level. The challenge, therefore, remained as to how to move from a descriptive, to a more critical interpretation of the body-maps (Maina et al., 2014).

Phase Two of the project provided the opportunity for discourse on and interpersonal reflection of both the process and the outcomes of the body-mapping exercise. Because the body-maps were so large, it was not feasible to use the original creations for discussion during the next contact session. Photographs of the superheroes and villains were included in a PowerPoint presentation that was used as a resource in the following contact session. This also provided all students with an easily accessible way to study and admire the body-maps of their fellow students.

Interpersonal and intrapersonal reflection

As preparation for the second session, students were motivated to study the roles of a teacher, as set out in the Minimum Requirements of Teacher Education Document (electronic source). With this background, the context was created for an analysis of the similarities and differences between the superheroes and villains. Students discussed common traits that appeared in most of their characters, and relayed, shared and interpreted their experiences, while completing the body-mapping activity.

Although valuable deductions could already have been made, the students in this module were such a diverse group of individuals, representing a myriad of ways to learn and teach, pedagogical and methodological approaches, prior life experiences, cultural and historical backgrounds, and familial relationships, that it is suspected that the inter-personal reflection during this process might not be enough to impact on their own identity as teachers. They may have had a good idea about charac-teristics that would indicate excellent teaching practice and professionalism, but it might not yet have spoken to their own social construction of identity, and influenced their apprenticeship of observation on their own development as teachers. It might not yet have transformed the way everyone thought about teaching. Groman (2015:6) ade-quately stated that "if we wish to have teachers who are going to transform the field of education, we must let them experience what it is to be transformed." Given these reasons, the value of the self-reflection of the participants conceptualised in the third phase of this project became clear.

During this discourse, a teaching assistant compiled a list of all the common positive and negative characteristics that students had listed on their body-maps and had reiterated during the group discussion (refer to Table 2).

Students were then invited to critically reflect upon their own praxis and perceptions in their quest to become a teacher, through the use of the table that summarises their work, as well as the roles specified in the Minimum Requirement Document (electronic source). In this way, students were offered the opportunity to translate the knowledge created in their body-maps to their own developing identity as teachers. Phase Three of the project attempted to create a safe environment, where students could access and explore their own lived experiences, local knowledge, aspirations, and even fears. They were also encouraged to reflect upon their experiences during Work Integrated Learning and look back upon the observations they had completed in reflection of their body-maps, and the lessons they had already presented during that time. In that manner, they could conceptualise their own strengths and weaknesses as developing teachers and identify areas in which they needed more practice, training, and personal and professional growth.

Intrapersonal reflection on professional identity involves acknowledging the inclination to possibly teach, as they were taught, and in this manner the apprenticeship of observation (Lortie, 1975) was addressed and deconstructed. The com-bined results of experience at tertiary level, as well as during Work Integrated Learning, and what they had learned from this activity, offered the opportunity for developing the necessary skills to improve their own teaching practice through critical thinking and analysis to identify alternative, more sufficient teaching methods.

Conclusion

It is important for trainers of student teachers to remember that students do not arrive in class as a tabula rasa or a blank slate. Consistent with this, it is valuable to avoid treating students as such. They arrive, armed not only with knowledge and ex-perience relevant to their work, but they also bring with them aspirations and ideals about their work and its importance that can serve to refresh the profession and its more longstanding members. At a more personal level, the visions and metaphors new teachers typically carry with them into the profession may, in turn, carry them through some darker and more difficult days of the job.

Personalising the body-mapping experience through the third phase of intrapersonal reflection on the identity of being a teacher strengthened the impact that this activity had on the students. This project clearly indicated that metaphors could be a rich and stimulating way for new teachers to talk about the experience of their perceptions, experiences and expectations of teaching (Thomas & Beauchamp, 2011). The enthusiasm with which students attempted the project, and their feedback on the value thereof, also concur with Thomas and Beauchamp's suggestion that "more attention needs to be paid to raising awareness of the process of professional identity development during teacher education programmes" (Thomas & Beauchamp, 2011:768). A follow-up article is planned where critical reflection of the students will be in-corporated to explore the reasons why this seems to be a very successful venture.

A strong case can thus be made for engaging pre-service teachers in a variety of dialogues (Akkerman & Meijer, 2011:315), including the use of metaphors about the development of their professional identities as part of an effective app-roach for preparing them for the complex and demanding profession they have chosen.

Initially, the project was created to identify the attributes of effective teachers, but then, after realising how much more potential there was for personal development, the aim of the activity changed towards growth. Promoting intrapersonal reflection contributed towards the social con-struction of the professional and personal identities of this group of pre-service teachers. It also contributed to the researcher's own identity as a teacher educator, and inspired the researcher towards a greater contribution to the personal development of student teachers. This desire is echoed in the words of Kazantakis, who has put it that "true teachers are those who use themselves as bridges over which they invite students to cross: then having facilitated the crossing, joyfully collapse, encouraging them to create their own" (electronic source).

Notes

i. Life Orientation is a compulsory subject for all South African learners from Grade 7 to 12. Students in this module are enrolled in the B.Ed. Senior Phase programme and have thus chosen the subject as one of their selective modules in order to become Life Orientation teachers for learners in Grade 7-9.

ii. The North West University requires students to complete 25 weeks of Work Integrated Learning throughout the four years of the B.Ed. programme (electronic source). During Work Integrated Learning (WIL), pre-service teachers are placed in schools and it includes aspects of learning from practice (e.g. observing and reflecting on lessons taught by others), as well as learning in practice (e.g. preparing, teaching and reflecting on lessons presented by oneself). The workplace-based component of WIL is structured, supervised, integrated into the learning programme and formally assessed (electronic source).

iii. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Akkerman SF & Meijer PC 2011. A dialogical approach to conceptualizing teacher identity. Teacher and Teacher Education, 27(2):308-319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.013 [ Links ]

Beauchamp C & Thomas L 2009. Understanding teacher identity: an overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(2):175-189. [ Links ]

Beltman S, Glass C, Dinham J, Chalk B & Nguyen B 2015. Drawing identity: Beginning pre-service teachers' professional identities. Issues in Educational Research, 25(3):225-245. Available at http://www.iier.org.au/iier25/beltman.html. Accessed 29 May 2017. [ Links ]

Botha CS 2012. High school teachers as agents of hope: A practical theological engagement. PhD dissertation. Bloemfontein, South Africa: University of the Free State. Available at http://scholar.ufs.ac.za:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11660/1469/BothaCS.pdf ?sequence=1. Accessed 29 May 2017. [ Links ]

Boud D & Hager P 2012. Re-thinking continuing professional development through changing metaphors and location in professional practices. Studies in Continuing Education, 34(1):17-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2011.608656 [ Links ]

Brett-MacLean P 2009. Body-mapping: embodying the self living with HIV/AIDS. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 180(7):740-741. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.090357 [ Links ]

Buchanan J 2015. Metaphors as two-way mirrors: Illuminating pre-service to in-service teacher identity development. The Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(10): Article 3. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2015v40n10.3 [ Links ]

Burr V 1995. An introduction to social constructionism. London, UK: Routledge. [ Links ]

Burr V 2003. Social constructionism (2nd ed). London, UK: Routledge. [ Links ]

Connelly FM & Clandinin DJ 1999. Shaping a professional identity: Stories of educational practice. London, Canada: The Althouse Press. [ Links ]

De Jager A, Tewson A, Ludlow B & Boydell KM 2016. Embodied ways of storying the self: A systematic review of body-mapping. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(2): Art. 22. Available at http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1602225. Accessed 16 March 2016. [ Links ]

Ebersöhn L 2015. Body mapping for resilience: Fostering adaptability with groups of youth in high risk and high need settings. In M McMahon & W Patton (eds). Ideas for career practitioners: Celebrating excellence in career practice. Brisbane, Australia: Australian Academic Press. [ Links ]

Eren A & Tekinarslan E 2013. Prospective teachers' metaphors: Teacher, teaching, learning, instructional material and evaluation courses. International Journal of Social Sciences and Education, 3(2):435-445. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Altay_Eren/publication/282185083_Prospective _Teachers%27_Metaphors_Teacher_Teaching_Learning_Instructional_Material_and_ Evaluation_Concepts/links/5606c88d08aeb5718ff753bc/Prospective-Teachers-Metaphors-Teacher-Teaching-Learning-Instructional-Material-and-Evaluation-Concepts.pdf. Accessed 28 May 2017. [ Links ]

Flores MA & Day C 2006. Contexts which shape and reshape new teachers' identities: A multi-perspective study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(2):219-232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.09.002 [ Links ]

Freer PK & Bennett D 2012. Developing musical and educational identities in university music students. Music Education Research, 14(3):265-284. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2012.712507 [ Links ]

Gastaldo D, Magalhães L, Carrasco C & Davy C 2012. Body-map storytelling as research: Methodological considerations for telling the stories of undocumented workers through body-mapping. Available at http://www.migrationhealth.ca/sites/default/files/Body-map_storytelling_as_reseach_HQ.pdf. Accessed 30 May 2017. [ Links ]

Goldstein LS 2005. Becoming a teacher as a hero's journey: Using metaphor in preservice teacher education. Teacher Education Quarterly, 32(1):7-24. [ Links ]

Griffin SM 2014. Meeting musical experience in the eye: Resonant work by teacher candidates through body mapping. Visions of Research in Music Education, 24:1-28. Available at http://www-usr.rider.edu/~vrme/v24n1/visions/Griffin_Meeting_Musical_Experience.pdf. Accessed 28 May 2017. [ Links ]

Groman JL 2015. What matters: Using arts-based methods to sculpt preservice teachers' philosophical beliefs. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 16(2):1-17. Available at http://www.ijea.org/v16n2/v16n2.pdf. Accessed 27 May 2017. [ Links ]

Huizinga J 1938. Homo ludens: Proeve ener bepaling vna het spelelement der cultuur [Trying to determine the playing element of culture]. Groningen, The Netherlands: Wolters-Noordhoff cop. [ Links ]

Lortie DC 1975. Schoolteacher: A sociological study. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Mahlios M, Massengill-Shaw D & Barry A 2010. Making sense of teaching through metaphors: a review across three studies. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 16(1):49-71. [ Links ]

Maina G, Sutankayo L, Chorney R & Caine V 2014. Living with and teaching about HIV: Engaging nursing students through body mapping. Nurse Education Today, 34(4):643-647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.05.004 [ Links ]

Martinez U & Nolte-Yupari S 2015. Story bound, map around: Stories, life, and learning. Art Education, 68(1):12-18. [ Links ]

Midgley W & Trimmer K 2013. Walking the labyrinth: A metaphorical understanding of approaches to metaphors for, in and of education research. In W Midgley, K Trimmer & A Davies (eds). Metaphors for, in and of education research. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [ Links ]

Palmer PJ 2007. The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher's life (10th ed). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Patchen T & Crawford T 2011. From gardeners to tour guides: The epistemological struggle revealed in teacher-generated metaphors of teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(3):286-298. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487110396716 [ Links ]

Saban A, Kocbeker BN & Saban A 2007. Prospective teachers' conceptions of teaching and learning revealed through metaphor analysis. Learning and Instruction, 17(2):123-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.01.003 [ Links ]

Shaw DM & Mahlios M 2008. Pre-service teachers' metaphors of teaching and literacy. Reading Psychology, 29(1):31-60. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702710701568397 [ Links ]

Solomon J 2007. Living with X: a body-mapping journey in the time of HIV and AIDS. Facilitator's guide. Johannesburg, South Africa: REPSSI. [ Links ]

Taylor LA 2017. How teachers become teacher researchers: Narrative as a tool for teacher identity construction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 61:16-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.09.008 [ Links ]

Theron L, Mitchell C, Smith A & Stuart J (eds.) 2011. Picturing research: Drawing as visual methodology. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Thomas L & Beauchamp C 2011. Understanding new teachers' professional identities through metaphor. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(4):762-769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.12.007 [ Links ]

Zeichner KM & Liston DP 1996. Reflective teaching: An introduction. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [ Links ]