Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.105 n.8 Pretoria Aug. 2015

https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJNEW.7932

RESEARCH

Prevalence of tobacco use among adults in South Africa: Results from the first South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

P ReddyI, II; K ZumaIII; O ShisanaIV, V; K JonasVI; R SewpaulVII

IPhD.Population Health, Health Systems and Innovation, Human Sciences Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa

IIPhD. Child and Family Studies, Department of Social Work, Faculty of Community and Health Sciences, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, Cape Town, South Africa

IIIPhD. Research Methodology and Data Centre, Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria, South Africa

IVBA, MA, ScD. Human Sciences Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa

VBA, MA, ScD. Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

VIMA. Population Health, Health Systems and Innovation, Human Sciences Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa

VIIMSc. Population Health, Health Systems and Innovation, Human Sciences Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Data on tobacco use have informed the effectiveness of South Africa (SA)'s tobacco control strategies over the past 20 years.

OBJECTIVE: To estimate the prevalence of tobacco use in the adult SA population according to certain demographic variables, and identify the factors influencing cessation attempts among current smokers.

METHODS: A multistage disproportionate nationally representative stratified cluster sample of households was selected for the South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, conducted in 2012. A sample of 10 000 households from 500 census enumerator areas was visited. A detailed questionnaire was administered to all consenting adults in each consenting household.

RESULTS: Of adult South Africans, 17.6% (95% confidence interval (CI) 6.3 - 18.9) currently smoke tobacco. Males (29.2%) had a prevalence four times that for females (7.3%) (odds ratio 5.20, 95% CI 4.39 - 6.16; p<0.001). The provinces with the highest current tobacco smoking prevalence were the Western Cape (32.9%), Northern Cape (31.2%) and Free State (27.4%). Among current tobacco smokers, 29.3% had been advised to quit smoking by a healthcare provider during the preceding year, 81.4% had noticed health warnings on tobacco packages, and 49.9% reported that the warning labels had led them to consider quitting.

CONCLUSION: A large proportion of adult South Africans continue to use tobacco. While considerable gains have been made in reducing tobacco use over the past 20 years, tobacco use and its determinants need to be monitored to ensure that tobacco control strategies remain effective.

Smoking is one of the major preventable causes of disease and premature death globally.[1] Tobacco is the second leading risk factor for the global burden of disease, accounting for 6.3% of disability-adjusted life-years lost[2] and causing six million deaths annually.[1] Since 1995 there has been a modest increase in tobacco consumption in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), but a consistent decline in high-income countries (HICs).[3] By 2030 it is estimated that tobacco will kill more than eight million people annually, with 80% of these deaths occurring in LMICs.[3] Consumers in LMICs such as South Africa (SA) are likely to be less informed about the adverse health consequences of tobacco use than those in HICs, and are therefore likely to bear the major health impact of tobacco unless an aggressive educational programme is mounted.[3,4]

SA epidemiological and economic data on tobacco use have informed tobacco control efforts since the 1980s, resulting in a halving of the prevalence of smoking in adults over the past 20 years.[4] Tobacco interventions used have included legislation such as the Tobacco Products Control Amendment Act No. 12 of 1999, hikes in excise duty on cigarettes, and health promotion interventions to educate and improve individuals' health knowledge.[4,5] Despite initial successes, there have been recent increases in tobacco use between 2008 and 2011 among SA youth, particularly girls.[4]

This study provides data on tobacco use among SA adults, and the factors influencing quitting among current smokers. The insights it provides into tobacco-related behaviours can be used to strengthen measures and health policies for tobacco control.

Methods

The first South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (SANHANES-1)[6] investigated the smoking status of South Africans aged >15 years through an interviewer-administered questionnaire survey and the collection of blood samples to measure serum cotinine levels. SANHANES-1 was a cross-sectional, biobehavioural survey providing baseline data as a foundation for future longitudinal studies. This article focuses on the self-reported tobacco-using behaviour of adults aged >18 years. The survey instrument included questions on the respondents' history of smoking tobacco, current use of other tobacco products, frequency and duration of use, and attempts to stop smoking tobacco or using other tobacco products. SANHANES-1 was conducted by the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) in 2012 and received approval from the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the HSRC (REC 6/16/11/11).

Sampling

The detailed sampling method is described in the main report.[6] Persons in all nine provinces aged >18 years were sampled, using a multistage disproportionate, stratified cluster sampling approach to select 10 000 households from a random sample of 500 census enumerator areas. All such adults in the household were interviewed in their homes, usually after hours, in a standardised manner by trained interviewers in the preferred language of the respondents. The reliability of the interviewers' survey techniques was ensured by reinterviewing 10% of the sample.

Respondents were considered to be current tobacco smokers if they reported that they currently smoked tobacco daily or less than daily. Similarly, current users of other tobacco products were defined as those who reported use of other tobacco products on a daily or less than daily basis. Other tobacco products were defined as handrolled cigarettes, pipes, cigars, cheroots and cigarillos, hookah, hubbly bubbly or water-pipe sessions, electronic cigarettes, snuff, chewing tobacco and smokeless tobacco. Reference to non-smokers in the text includes ex-smokers.

Data management and statistical analysis

Data were double-entered and verified using Census Survey Processing (CS Pro) software version 5.0 (US Census Bureau) and converted to the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for further exploration. Sampling weights were computed to account for unequal sampling probabilities and benchmarking to 2012 mid-year population estimates. Data on tobacco use were analysed for adults aged >18 years. Weighted data were analysed using STATA version 12 (Stata Corporation, USA). Estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported with odds ratios (ORs) as measures and direction of association. Chi-square and t-tests were used for categorical and continuous random variables, respectively. A p-value of <0.05 indicated statistical significance. Logistic regression analyses were conducted on the subsample of current tobacco smokers to determine the factors associated with having tried to stop smoking in the preceding 12 months in this group. The variables found to be significant in the univariate models were used in the multivariate model.

Results

Demographic profile of the sample

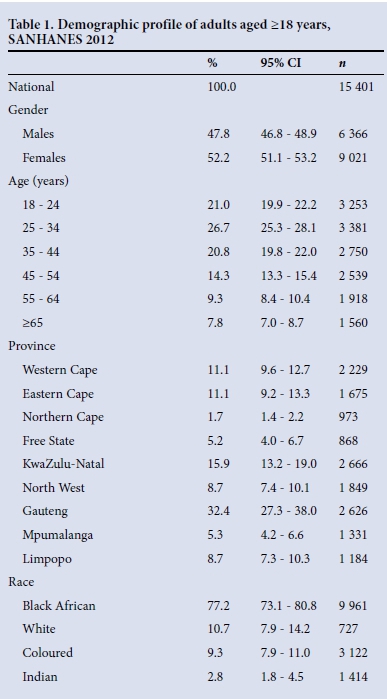

Of the adult sample of 15 401, 52.2% were females (Table 1), 77.2% classified themselves as black Africans, 10.7% as white, 9.3% as coloured and 2.8% as of Indian descent, and 82.8% were aged 18 -54 years.

Current tobacco smoking

The tobacco smoking status of the respondents is shown in Table 2. Of the 15 401 interviewed, 13 897 (90.2%) indicated their tobacco smoking status. The national prevalence of current tobacco smoking among adults was 17.6% (95% CI 16.3 - 18.9), with 15.9% (95% CI 14.7 - 17.2) being daily smokers and 1.7% (95% CI 1.4 - 2.0) less than daily smokers.

The prevalence of current tobacco smoking among males (29.2%) was four times that among females (7.3%) (OR 5.20, 95% CI 4.39 - 6.16; p<0.001).

The provinces with the highest current tobacco smoking rates were the Western Cape (32.9%), Northern Cape (31.2%) and Free State (27.4%); North West and Limpopo had the lowest rates (12.7% and 12.8%, respectively). Coloured adults had a significantly higher current smoking prevalence (40.1%) than Indians (22.1%) (p<0.001), whites (15.3%) (p<0.001) and black Africans (15.1%) (p<0.001).

Adults aged 18 - 24 (13.6%), and >65 years (10.8%) had significantly lower current tobacco smoking prevalences than those aged 25 - 34 (18.5%), 35 - 44 (19.7%), 45 - 54 (21.2%) and 55 - 64 years (19.5%) (p<0.001 for all).

Use of other tobacco products

Nationally, 5.2% of adults reported current use of other tobacco products, with 4.2% being daily users and 1.0% less than daily users (Table 3). Significantly (p<0.001) more males (6.8%) than females (3.7%) reported current use of other tobacco products (OR 1.90, 95% CI 1.52 - 2.36).

Among males, there was no significant variation in current use of other tobacco products by age group, whereas among females this increased with age. Females aged 18 - 24 (1.8%) and 25 - 34 years (2.1%) had a significantly lower prevalence of current use of other tobacco products than those aged 35 - 44 (4.6%), 45 - 54 (4.9%), 55 - 64 (6.1%) and >65 years (6.2%). The Free State had the highest provincial prevalence of current use of other tobacco products (18.3%), and North West (2.1%) the lowest.

Significantly more coloured adults (7.7%) than Indian (3.0%) (p=0.009) and white (2.2%) (p<0.001) adults reported current use of other tobacco products. Furthermore, significantly more black African adults (5.4%) than white adults (2.2%) reported current use of other tobacco products (p<0.001).

Current use of any tobacco product

Nationally, 20.1% (95% CI 18.7 - 21.5) of adults reported current use of any tobacco product (either smoking or use of other tobacco products). Males had a significantly higher prevalence of current tobacco use (31.0%) than females (10.3%) (OR 3.90, 95% CI 3.37 - 4.52; p<0.001).

Significantly fewer adults aged 18 - 24 (14.8%) and >65 years (15.9%) than those aged 25 - 34 (20.2%), 35 - 44 (22.5%), 45 - 54 (24.4%) and 55 - 64 years (22.8%) currently used tobacco (p<0.05 for all).

The highest prevalence of current tobacco use was observed in the Free State (36.7%) and Western Cape (35.8%), and the lowest in North West (14.2%). The prevalence was significantly higher among coloured adults (43.1%) than among Indians (23.5%) (p<0.001), black Africans (17.7%) (p<0.001) and whites (17.1%) (p<0.001).

Factors affecting tobacco smoking cessation attempts

Among current tobacco smokers, 29.3% reported that they had been advised to quit smoking tobacco during a visit to a healthcare practitioner during the 12 months preceding the survey, and 47.8% had tried to quit smoking during that time (Table 4).

Significantly fewer male (26.5%) than female (39.3%) current tobacco smokers reported being advised to quit smoking (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.42 - 0.74; p<0.001). The proportions of respondents who had been advised to quit increased with age group. Significantly more current tobacco smokers aged 55 - 64 (41.6%) and >65 years (52.3%) were advised to quit smoking by a healthcare practitioner than those aged 35 - 44 (30.2%) (p=0.020 and p=0.005, respectively), 25 - 34 (24.3%) (p<0.001 and p<0.001, respectively) and 18 - 24 years (14.7%) (p<0.001 and p<0.001, respectively). Of the provinces, Mpumalanga (18.9%) had the lowest proportion of current smokers who had been advised to quit smoking, and North West (38.9%) the highest. Significantly more Indian (53.7%) and coloured (36.2%) current smokers than black Africans (25.3%) (p=0.035 and p<0.001, respectively) reported being advised to quit smoking.

Attempts to quit tobacco smoking in the past year did not differ significantly by gender (OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.71 - 1.22; p=0.607), or by race or age for all within-group pairwise tests. The prevalence of having tried to quit smoking was highest in the Eastern Cape (54.2%) and KwaZulu-Natal (53.8%) and lowest in Limpopo (38.4%).

Among current tobacco smokers, 81.4% reported that they had noticed health warnings on tobacco packages during the 30 days preceding the survey, and 49.9% reported that these labels had led them to think about quitting smoking.

There was no significant association of gender (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.71 - 1.37; p=0.955) or age in the likelihood of having noticed health warnings on tobacco packages among current smokers. The Northern Cape (93.2%) had the highest proportion of current smokers who had noticed health warnings on tobacco packages. Significantly more coloured (88.0%) and Indian (89.2%) than black African (78.4%) (p<0.001 and p=0.032, respectively) current smokers had noticed health warnings on tobacco packages.

There was no significant variation by gender in the prevalence of current smokers who reported that warning labels on tobacco packages led them to think about quitting smoking (OR 1.17, 95% CI 0.89 -1.54; p=0.248). Significantly more current smokers aged 45 - 54 (56.2%) than those aged 35 - 44 years (45.2%) reported that warning labels on tobacco packages led them to think about quitting smoking (p=0.042). The Northern Cape had the highest proportion of current smokers who reported that warning labels led them to think about quitting (61.1%), and Limpopo the lowest (35.7%). Significantly more black African (51.8%) and Indian (54.0%) current smokers than white current smokers (37.1%) reported that warning labels led them to think about quitting (p=0.022 and p=0.015, respectively).

Among current tobacco smokers, no statistically significant univariate associations were found between having tried to stop smoking tobacco in the past 12 months and each of the categories gender, age group and race (Table 5). Having been advised to quit using tobacco during a visit to a healthcare provider during the past 12 months and having noticed health warnings on tobacco packages in the past 30 days were significantly associated with attempts to stop smoking tobacco in both the univariate (OR 3.97, 95% CI 2.94 - 5.34 and OR 2.00, 95% CI 1.43 - 2.79, respectively) and multivariate (OR 3.79, 95% CI 2.80 - 5.14 and OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.21 - 2.41, respectively) logistic regression models.

Prevalence of exposure to secondhand smoke

Among current users of any tobacco products, 56.4% reported that someone smoked in their home (either daily or less than daily), while among non-current users of tobacco products this figure was 13.0% (Table 6).

Among current tobacco users, daily exposure to tobacco smoke in the home did not vary significantly by gender (OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.86 - 1.44; p=0.409) or age group. The Northern Cape and Western Cape had the highest proportions of current smokers who reported that someone smoked daily in their homes (64.9% and 64.3%, respectively) while the Eastern Cape and Mpumalanga had the lowest proportions (41.9% and 42.5%, respectively). Significantly fewer black African (45.1%) than coloured (67.1%) and white (59.9%) current tobacco users reported daily exposure to tobacco smoke in their homes (p<0.001 and p=0.049, respectively).

Among adults who did not currently use tobacco, significantly fewer males (8.4%) than females (11.8%) (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.58 - 0.82; p<0.001) reported that someone smoked daily in their homes. Significantly more 18 - 24-year-old non-current users of tobacco (13.8%) than those aged 25 - 34 (9.0%), 35 - 44 (9.4%), 45 - 54 (9.9%) and >65 years (8.3%) reported that someone smoked daily in their homes (p<0.001, p=0.002, p=0.008 and p=0.001, respectively). The Western Cape had the highest proportion of non-current tobacco users who reported that someone smoked daily in their homes (18.6%), and North West the lowest (6.9%). Significantly more coloured (24.5%) and Indian (20.3%) than black African (9.3%) (p<0.001 and p=0.005, respectively) and white (8.5%) (p<0.001 and p=0.007, respectively) non-current tobacco users reported that someone smoked daily in their homes.

Discussion

The SANHANES-1 study collected self-reported data on tobacco-using behaviour among 13 897 SA adults aged >18 years. The study revealed significantly greater use of tobacco products by males than by females, perhaps because tobacco use is believed to be more socially acceptable among men than women in many SA communities, and because men often have more disposable income to buy tobacco products.[4]

There were considerable variations in tobacco use between the provinces and different racial groups in SA, perhaps reflecting differences in sociocultural and demographic determinants. For example, tobacco smoking rates are very high among coloured people, who comprise a high proportion of the Western Cape and Northern Cape populations - tobacco smoking rates in the Western Cape were 39.6% for men and 26.8% for women, and in the Northern Cape 38.3% for men and 24.5% for women. High rates of smoking among pregnant women in the Western Cape have been reported in other studies.[7] Surprisingly high prevalences of use of other tobacco products were observed among both males and females in the Northern Cape and Free State, and further investigation is needed to ascertain the factors driving these high rates.

Economic factors are also important in determining smoking prevalence rates, as tobacco use in LMICs such as SA is often highest among poorly educated, urban men and women who have low incomes.[8-11]

These sociocultural and geographical differences in tobacco use and prevalence suggest that tailored culture- and context-specific interventions need to be designed for smoking prevention and cessation among SA's heterogeneous and rapidly changing populations. Tobacco control interventions such as hikes in excise taxes are likely to be more effective in citizens with lower disposable income. A case can be made for increasing excise duty on cigarettes from the current 51% of total price to nearer the 75% employed by countries with progressive tobacco control policies such as Canada.[12]

The recent increase in smoking rates among young people and girls from 2008 to 2011, seen in the Global Youth Tobacco Surveys,[4] has occurred despite the initial success of tobacco control legislation and public health policies of the past 20 years that resulted in a 30% reduction in smoking prevalence among school learners during that time. This suggests that the strategies the tobacco industry uses to encourage young people (particularly girls) to smoke have been successful. Research shows that tobacco use is most often initiated and established during adolescence and young adulthood, with nearly nine out of ten smokers starting the habit by the age of 18 years, and 99% starting by the age of 26.[13]

Surprisingly few current smokers (29.3%) reported that they had been advised to quit the use of tobacco products. Health professionals therefore need to escalate their efforts in advising users to quit, so as to avoid missed opportunities for prevention (in over 70% of smokers). Of current smokers, 47.8% had tried to quit and 49.9% reported that the health warning labels on tobacco packages made them think about quitting, suggesting that health warning labels may be effective in encouraging smoking cessation. This effect may be augmented when combined with plain packaging, as is done in Australia. Those who noticed warning labels on tobacco packages were 1.7 times more likely to attempt to quit smoking than those who did not notice warning labels.

Respondents who received advice to quit smoking from a healthcare provider were 3.8 times more likely to attempt to quit than those who did not receive advice. Women received advice to quit smoking much more often than men.

Of concern is the high prevalence of non-smokers who are exposed to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS). It is estimated that of the six million deaths that tobacco causes annually, 10% (600 000 deaths) occur among non-smokers who have been exposed to ETS.[14] ETS is particularly harmful for children who live in homes with smokers. Notably, the SA government has introduced legislation to ban smoking in cars in which children under the age of 12 are travelling.

Conclusion

The efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a well-tested set of tobacco control policies and interventions have been clearly established over several decades in many countries around the world, at various income levels and in many different cultures. SANHANES-1 shows that this is also true of SA, where national smoking prevalence rates fell from 32% in 1994 to 16.4% in 2011,[6] during a time when the government was introducing a host of tobacco control legislation and hiking excise duties on cigarettes. However, research and monitoring of tobacco control must continue to develop policies and interventions to decrease smoking prevalence rates further. In addition, research is needed to counter the ever-evolving strategies the tobacco industry uses to market its products, especially to young people and girls.

Lastly, longitudinal studies such as SANHANES-1 should be repeated at regular intervals in the future to monitor the course of the tobacco epidemic, in accordance with the guidelines of the World Health Organization's Framework Convention on Tobacco Control,[15] to which SA is a signatory. These studies should form part of comparative datasets with other LMICs and HICs aimed at strengthening transnational co-ordination in tobacco control while facing an industry that is transnational in structure and marketing methods.

Acknowledgements. We wish to express our gratitude to the respondents who participated in the survey by completing the questionnaire. We appreciate the work done by our colleagues, the HSRC researchers who developed the questionnaires and collected the data that made it possible for us to prepare the paper.

Funding. The SANHANES-1 survey was funded by the Department for International Development, UK, and the South African National Department of Health.

References

1. World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Risks Report: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GlobalHealthRisks_report_full.pdf (accessed 20 January 2015). [ Links ]

2. Lim S, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380(9859):2224-2260. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8] [ Links ]

3. World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2011: Warning About the Dangers of Tobacco. Geneva: WHO, 2011. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789240687813_eng.pdf (accessed 14 May 2014). [ Links ]

4. Reddy P, James S, Sewpaul R, et al. A decade of tobacco control: The South African case of politics, health policy, health promotion and behaviour change. S Afr Med J 2013;103(11):835-840. [http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.6910] [ Links ]

5. Reddy P, Meyer-Weitz A, Yach D. Smoking status, knowledge of health effects and attitudes towards tobacco control in South Africa. S Afr Med J 1996;86(11):1389-1393. [ Links ]

6. Shisana O, Labadarios D, Rehle T, et al., and the SANHANES-1 Team. South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (SANHANES-1): 2014 Edition. Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2014. http://www.hsrc.ac.za/uploads/pageNews/72/SANHANES-launch (accessed 20 January 2015). [ Links ]

7. Chopra M, Lawn JE, Sanders D, et al. Achieving the health Millennium Development Goals for South Africa: Challenges and priorities. Lancet 2009;374(9694):1023-1031. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61122-3] [ Links ]

8. Blakely T, Hales S, Kleft C, Wilson N, Woodward A. The global distribution of risk factors by poverty level. Bull World Health Organ 2005;83(2):118-126. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0042-96862005000200012] [ Links ]

9. Bobak M, Jha P, Nguyen S, Jarvis M. Poverty and smoking. In: Jha P, Chaloupka F, eds. Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2000. [ Links ]

10. Pampel FC. Patterns of tobacco use in the early stage of the epidemic: Malawi and Zambia 2000-2002. Am J Public Health 2005;95(6):1009-1015. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.056895] [ Links ]

11. Blecher EH, van Walbeek CP. Cigarette affordability trends: An update and some methodological comments. Tob Control 2009;18(3):167-175. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tc.2008.026682] [ Links ]

12. Gabler N, Katz D. Contraband Tobacco in Canada: Tax Policies and Black Market Incentives. Studies in Risk and Regulation, Fraser Institute, 2010. http://www.fraserinstitute.org/uploadedFiles/fraser-ca/Content/research-news/reearch/publications/contraband-tobacco-in-canada%281%29.Pdf (accessed20 January 2015). [ Links ]

13. US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS). Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2012. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/preventing-youth-tobacco-use/full-report.pdf (accessed 20 January 2015). [ Links ]

14. World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Tuberculosis Epidemic. Global Tuberculosis Control Reports, 2014. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ (accessed 20 January 2015). [ Links ]

15. World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. A56/8. Geneva: WHO, 2003. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241591013.pdf (accessed 31 April 2015). [ Links ]

Accepted 15 June 2015

Corresponding author: P Reddy (preddy@hsrc.ac.za)