Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.73 n.2 Pretoria 2017

https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i2.3837

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

South African religious demography: The 2013 General Household Survey

Willem J. Schoeman

Department of Practical Theology, University of the Free State, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The South African religious landscape is diverse and has a profound effect on the role that faith communities may and should play within this context. The General Household Survey (2013), conducted by StatsSA, gave, for the first time since the census of 2001, a picture of the South African religious profile. The aim is to use religious affiliation and adherence as indicators to plot this landscape. These indicators provide a framework to define and explore the role of the church and faith communities in the South African society. How should secularisation, evangelism, social engagement and the prophetic voice of the church be viewed within this context? The aim of this article is to explore these and other questions within the 2013 General Household Survey as a demographical framework to describe a South African reality for faith communities.

The South African religious landscape is diverse and has a profound effect on the role that faith communities and its members may and should play within this context. The General Household Survey (GHS), conducted in 2013 by Statistics South Africa (StatsSA), gave, for the first time since the census of 2001, a picture of the South African religious profile. The aim of this article is to use religious affiliation and adherence as indicators to plot the South African religious landscape. These indicators, affiliation and adherence, provide a framework to define and explore the role of churches and faith communities in the South African society. This may help to plot aspects such as secularisation, evangelism, social engagement and the prophetic voice of the church and faith communities within the South African context.

The South African religious demography may also be placed within a broader framework as part of the demographic movement of Christianity towards the South and as these churches grow, they will define their own ways that differ from the preferences from the North (Jenkins 2002:14). The practices of rising churches in the South reflect a newness that cannot only be explained in terms of culture, region or race:

What most strikingly unites the otherwise diverse Southern churches is that in most cases, Christianity as a mass popular movement is a relatively new creation, so that first- and second-generation converts are well represented in the various congregations. (Jenkins 2002:137)

The challenge is to describe and analyse these developments sociologically but also theologically. Southern Christianity is not a transplant of the older or Northern version, it is a new and developing entity (Jenkins 2002:214). The critical challenge is therefore to position the South African religious demographics within this movement towards the 'South'.

The article will start with a brief reference to the religious demographic picture of South Africa since 1911 and then place the emphasis on the GHS survey of 2013 and its implications for Christian churches and faith communities. Surveys contribute to the bigger picture and help in defining the context and environment for churches and congregations (see Hermans & Schoeman 2015). The GHS survey of 2013 is such a survey that could help churches, from a quantitative perspective, to position themselves within the South African context.

The study demography assists, from a quantitative perspective, to describe the characteristics, composition and changes within a population (Holdsworth et al. 2013:8). The study's religious demography helps one to understand the role of religion in different communities and in society as a whole. How did the religious demography change over time and specifically in South Africa? A question regarding religion was included in the first census in South Africa in 1911, and in all the subsequent censuses until 2001, but not in the 2011 census. Religion however, featured again in the GHS of 2013. How does this survey help us to understand the position and role of religion in the South African society? What is the influence of religion on the values and attitudes of South Africans? What role should religion and faith communities play in the South African society? These questions will be part of the argument in this article. Another question is about the position of South Africa within the bigger religious demographic picture. Is the Christian population growing or are some of the Northern hemisphere characteristics part of the South African landscape?

Christians in South Africa - 1911-2001

The first national census was undertaken in 1911 and included a question regarding religious affiliation. Hendriks (2005:27-85) gives a comprehensive report on the religious affiliation of the South African population during this period. From 1910 until 1980 the Christian population showed a steady growth but a decline was reported after 1980 (see Table 1) (Erasmus & Hendriks 2001:52). The question about religion in the 1991 and 1996 censuses was optional, because of the point of view that religion was a personal issue (Erasmus & Hendriks 2001:62). Could the decline that was reported during the 1990s be attributed to a process of secularisation? Erasmus and Hendriks (2005:102) argue that this decline is typical of Western Christianity and was becoming observable in South Africa, but they also argue that this is debatable because other studies indicated a more gradual growth since 2000.

The 2001 census questionnaire used the 1996 one as a basis, but the question about religion was not optional anymore and this improved the credibility of the results (Erasmus & Hendriks 2005:89). A general trend of the 2001 census data (see Table 2) on religion is the fact that a growing number of people in South Africa associate with Christianity (Erasmus & Hendriks 2005:109). The 2001 results for the white and coloured population groups indicate a decline, but the percentages of Christian in the black and Asian population groups were still growing (Erasmus & Hendriks 2005:102). Changes within the black population group, as the dominant group (79% of the population), play an important role in the growth of Christianity, but as a general trend 'established churches are losing their market share, while the gain transposes to the AIC's, the Pentecostal and the new Independent Churches' (Hendriks 2005:83). This argument would be in line with the Southern movement of Christianity (see Jenkins 2002). The next important question is to establish what happened to the South African religious landscape after the 2001 census.

The religious landscape after 2001

The 2011 national state census did not include religion as a question and it is therefore difficult to give a description of the changes that have taken place in the South African religious population since 2001. The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life published a comprehensive report in April 2010 on Tolerance and tension: Islam and Christianity in sub-Saharan Africa. This report gives an indication of the religious demography of South Africa since 2001 and reports that 87% of the population adheres to the Christian religion (Lugo & Cooperman 2010:20-23). This indicates an increase of the Christian population since 2001.

Nominal membership or affiliation is one aspect of religious participation, but religion could also be described in terms of participation and adherence. WIN-Gallup International published a world report on religiosity in 2012, and respondents were asked to answer the following question: 'Irrespective of whether you attend a place of worship or not, would you say you are a religious person, not a religious person, or a convinced atheist?' This report states that religiosity declined in South Africa from 83% in 2005 to 64% in 2012 (Shahid & Zuettel 2012:6). The relationship between nominal membership and religiosity or commitment is not always clear. The Pew-report of 2010 makes the following findings regarding religious commitment:

• Seventy-four per cent (74%) of the South African population indicates that religion plays an important role in their lives (Lugo & Cooperman 2010:3).

• Sixty per cent (60%) of South African Christians attend worship services on a weekly basis (Lugo & Cooperman 2010:27).

• Within the South African population, 89% is being raised in the Christian tradition, but only 87% indicated in 2010 that they were Christians. This is a decline of 2% (Lugo & Cooperman 2010:12), and may indicate a decline in adherence towards the Christian religion.

The General Household Survey 2013

Since 2002 StatsSA has been conducting an annual household survey. These surveys cover all private households in the nine provinces of South Africa, and residents in workers' hostels. The surveys do not cover other collective living quarters such as students' hostels, old age homes, hospitals, prisons and military barracks, and are, therefore, only representative of non-institutionalised and non-military persons and households in South Africa (Statistics South Africa 2014:10). In the surveys a multi-stage, stratified random sample is used and field workers (employed by StatsSA) conduct interviews at all the sampled units. In the case of GHS 2013, a total of 31 486 sampled households were visited across the country and 25 786 (including multiple households) were successfully interviewed during face-to-face interviews (Statistics South Africa 2014). Religion was for the first time included in the GHS 2013. Two questions about religion from the 2010 Pew Research Centre's survey (see Lugo & Cooperman 2010:20-23) were submitted to StatsSA, and were included in the 2013 questionnaire of the GHS:

• How would you describe your religious affiliation?

• Aside from weddings and funerals, how often do you attend religious services?

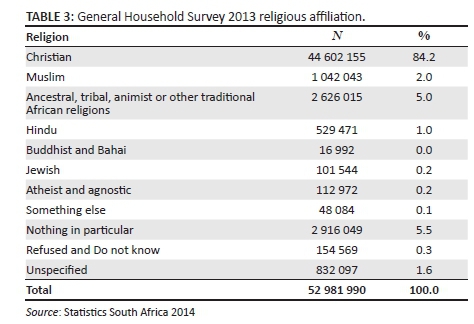

Table 31 reports on the religious affiliation of the South African population. In 2013 a majority (84.2%) of South Africans described their religious affiliation as 'Christian'; this is an increase from the 79.8% that was reported in the 2001 census. Ancestral or traditional African religions are practised by 5% of the population and the category 'nothing in particular' 5.5%. Table 4 gives a description of the distribution of the different religions in the nine provinces. The Northern Cape (97.9%) and Free State (95.5%) report the highest percentage of Christians. Muslims, that comprised 2% of the total population, were predominantly found in the Western Cape (7.3%), KwaZulu Natal (2.6%) and Gauteng (1.5%). Hindus comprised about 1% of the total population, but 3.9% of the population of KwaZulu- Natal.

The religious affiliation and age within the four race groups is reported in Table 5 to Table 8. The discussion will only focus on a few notable aspects from these four tables. Within the black African group in the age group 25 to 34 years, 37% are affiliated with the Muslim religion, while, within this age group only 17.7% black Africans are Christian. Are young black African persons more attracted towards the Muslim religion? This is, for example, not the case with the coloured group for the same age group (15.4% Muslim and 15.7% Christian). The Buddist and Bahai religions are 'over'-represented in the age group 0 to 14 years in the black African and Indian or Asian population groups. This is also the case with the Hindu religion in Indian or Asian and white population groups for the same age group. Could this be explained in terms of the schools the children are attending? Within the white population group, there is not an 'under'-representation in terms of the younger population groups for the Christian religion.

The different patterns in terms of religious observance give a description of the commitment of the membership of the different religious groups (Table 9). This religious service or ritual is mostly in the form of a weekly worship service. Almost three-quarters (74.3%) of those belonging to the Muslim religion attend a weekly service. By comparison, 56.4% of Christians and 55.0% of Hindus attend services on a weekly basis. This can be compared with other surveys. The 2004 South African Social Attitudes (SASA) report indicates that 51% of the respondents replied that they attend worship services at least once a week and 25% at least once a month (Rule & Mncwango 2010:189). This attendance figure is in line with the 2001 HSRC survey where 45% indicated that they attended worship services at least once a week (Rule & Mncwango 2010:189). Table 10 describes the role of gender in terms of religious observance for the Christian religion. For women 61.4% attend worship services on a weekly basis, as compared to the 50.7% for men. In terms of population groups (Table 11), the Christian religion group and the Indian or Asian group attend worship services most, followed by the black group.

The 2013 GHS data on religious affiliation and observance help to present a more recent and reliable picture of the South African landscape. In surveys of this nature, there is a consistent overreporting on issues like the frequency of worship attendance and voting in elections. There is a tendency to provide answers that the respondents feel are socially acceptable or politically correct (Rule & Mncwango 2010:185). This may be too positive a picture (see Rule & Mncwango 2010:190), but at least it gives an indication of the position and role of religion within the South African context. It helps the different religions and denominations to position themselves within the South African religious landscape. An important question to ask is whether South Africa could be viewed as a Christian or secularised country. The demographic description and position of the Christian faith in South Africa is not the same as, for example, in the Northern hemisphere.

The religious demography as a reality for faith communities

From the 2001 census, the GHS 2013 and other surveys an increase in the adherence to the Christian religion has been reported: '[A]t least in what they say, South Africans are a very religious people' (Rule & Mncwango 2010:187). But what is the influence and role of Christians in the South African society? The second South African Social Attitudes (SASA) (Rule & Mncwango 2010) report may be used as an instrument to provide some guidelines in answering this question.

Trust plays an important role in a democratic society, as it consolidates the society and its institutions. Do the citizens believe in or trust the institutions that serve them? (Rule & Langa 2010:25). Christians are organised in churches (and also denominations and congregations), and 'churches appear consistently to enjoy the highest level of trust across the country, with four out of five South Africans indicating that they either or strongly trust churches' (Rule & Langa 2010:25). Institutions that are at the bottom of the relative levels of trust are the police, the Scorpions Unit, local police stations and labour unions (Rule & Langa 2010:25). This places the Church and its membership in an important position to have an influence on the South African society.

The following findings from the second SASA report about the beliefs and practices of Christians may serve as an illustration of the position of this belief system:

• Their beliefs about God: Seventy-four per cent (74%) believe that God exists and they have no doubts about it (Rule & Mncwango 2010:187):

South Africa emerges as strongest in its popular belief in God, even more than a decade after the same statements were put to nationally representative samples in 16 other countries, namely in Europe, but including the relatively religious Philippines, Poland, United States, Northern Ireland and Ireland. (Rule & Mncwango 2010:188)

• The prayer of Christians: About 6 out of 10 (63%) of the respondents reported that they prayed once or several times a day (Rule & Mncwango 2010:191).

• Honesty in dealing with the state: Two questions were asked, one about tax compliance and the other on honesty regarding accessing a government social grant. Only 49% indicated that it was seriously wrong if taxpayers did not report all their income in order to pay tax, while 58% reported that it was seriously wrong to submit incorrect information in order to qualify for a social grant:

It emerges that many South Africans have a flexible attitude towards their tax obligations on the one hand, and the extent to which they can access cash benefits from the state on the other. (Rule & Mncwango 2010:194)

In conclusion, the second SASA report stated that Christians held strong orthodox views in relation to the Christian doctrine, claiming to believe in God (74%) and in the Bible as the literal word of God (64%); 'Jesus is the solution to all the world's problems' (76%) (Rule & Mncwango 2010:196). A majority has conservative views on support for capital punishment and oppose abortion (Rule & Mncwango 2010:196). This may also be seen as being in step with Christian communities in the South that place an emphasis on the Bible and biblical authority that differs from the outlook common in Europe and North America (Jenkins 2006:8). A critical question may be posed about the role that Christians play in dealing with the state and its institutions: Should honesty not have played a more important role, or how do Christians and churches position themselves within society?

A few concluding remarks on the South African demographic landscape

These concluding remarks are made from the position or perspective of the Christian churches and their membership within the South African society. The first remark is based on a broader perspective of the Church, the different denominations and their membership within society.

Is South Africa a Christian or secularised country, or what is the position of religion within the South African society? The vast majority of South Africans is linked to the Christian faith, but it is not an easy answer to describe its position in terms of secularisation. Although there is a spectrum of understanding of the concept (see Paas 2013:92-96), the following definition may help:

Secularisation is a process of change by which the sacred gives way to the secular, whether in matters of personal faith, institutional practice, or social power. It involves a transition in which things once revered become ordinary, the sanctified becomes mundane, and things other-worldly may lose their prefix. Whereas 'secularity' refers to a condition of sacredlessness, and 'secularism' is the ideology devoted to such a state, secularisation is a historical dynamic that may occur gradually or suddenly and is sometimes temporary and occasionally. (Demerath 2007:65-66)

Secularisation refers to a process of religious change. It is not only a linear process but refers also to a change in influence which implies that the Church and Christians should reposition and redefine themselves within the current South African context. This needs to be developed further in terms of a theological and sociological understanding and theory.

Secondly, what would the religious landscape imply for the different congregations? Congregations have to redefine relationships as a partnership with other Christian institutions and not as an evangelism project to convert people to Christianity. The bigger South African picture gives congregations important contextual information about their role and positioning in society and local community. The National Development Plan states that faith plays, within the South African society, an important role in the generation of social capital and that churches and congregations may be useful 'for the social cohesion project because they are a repository of social values' (National Development Plan 2012:27). The plan identifies the elimination of poverty and the reduction of inequality as important strategic goals for the country, and seeks to develop high levels of social cohesion and social mobility (National Development Plan 2012:29). Congregations have an important prophetic and practical role to play in this regard. This may start as an ecumenical dialogue using ethical issues (e.g. honesty and corruption in dealing with the state) as a starting point:

Given the present and future distribution of Christians worldwide, a case can be made that understanding the religion in its non-Western context is a prime necessity for anyone seeking to understand the emerging world. (Jenkins 2002:215)

This would mean, from a South African perspective, that the post-apartheid and post-colonial position of religion within the current South African context should be taken seriously. The 2013 GHS data on religious affiliation and adherence provide important religious demographic markers to describe and redefine the position and role of religion within the South African context.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Demerath, N., 2007, 'Secularization and sacralization decontructed and reconstructed', in J.A. Beckford & J. Demerath (eds.), The SAGE handbook of the sociology of religion, pp. 57-80, Sage, Los Angeles. [ Links ]

Erasmus, J.C. & Hendriks, H.J., 2001, 'Interpreting the new religious landscape in post-apartheid South Africa', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 109(March), 41-65. [ Links ]

Erasmus, J.C. & Hendriks, H.J., 2005, 'Religion in South Africa: The 2001 population census data', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 121(March), 88-111. [ Links ]

Hendriks, J., 2005, 'Census 2001: Religion in South Africa with denominational trends 1911-2001', in J. Symington (ed.), South African Christian Handbook 2005-2006, pp. 27-85, Tydskriftemaatskappy van die NG Kerk, Wellington. [ Links ]

Hermans, C. & Schoeman, W.J., 2015, 'Survey research in practical theology and congregational studies', Acta Theologica, Suppl 22, 45-63. [ Links ]

Holdsworth, C., Finney N., Marshall A. & Norman P., 2013, Population and society, Sage Publications, London. [ Links ]

Jenkins, P., 2002, The next Christendom: The coming of global Christianity, Oxford University Press, New York. [ Links ]

Jenkins, P., 2006, The new faces of Christianity: Believing the Bible in the global south, Oxford University Press, New York. [ Links ]

Lugo, L. & Cooperman, A., 2010, Tolerance and tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa, Pew Research Center, Washington. [ Links ]

National Development Plan, 2012, 'National Development Plan 2030. Our Future-make it work', viewed 12 January 2015, from http://www.poa.gov.za/news/Documents/NPC%20National%20Development%20Plan%20Vision%202030%20-lo-res.pdf [ Links ]

Paas, S., 2013, 'Missionary ecclesiology in an age of individualization', Calvin Theological Journal 48(5) 91-106. [ Links ]

Rule, S. & Langa, Z., 2010, 'South Africans' views about national priorities and the trustworthiness of institutions', in B. Roberts, W. Kivilu & Y. D. Davids (eds.), South African Social Attitudes 2nd report: Reflections on the Age of Hope, pp. 19-30, HSRC Press, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Rule, S. & Mncwango, B., 2010, 'Christianity in South Africa: Theory and practice', in B. Roberts, M. wa Kivilu & Y. D. Davids (eds.), South African Social Attitudes 2nd report: Reflections on the Age of Hope, pp. 185-198, HSRC Press, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Shahid, R. & Zuettel, I., 2012, Global index of religion and atheism, P WIN-Gallup International, Zürich. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa, 2014, General household survey 2013, StatsSA, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Willem Schoeman

schoemanw@ufs.ac.za

Received: 14 Aug. 2016

Accepted: 01 Nov. 2016

Published: 16 Feb. 2017

Note: This article is published in the section Practical Theology of the Society for Practical Theology in South Africa.

1 Table 3 to Table 11 are compiled from GHS 2013 data received from Statistics South Africa.