Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.78 n.1 Pretoria 2022

https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v78i1.7740

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Ancient Israelite conceptual system for heaven in the Hebrew Bible

Adriaan Lamprecht

Department of Ancient Languages and Text Studies, Faculty of Theology, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The traditional view reflected in biblical Hebrew dictionaries and textbooks that heaven is construed as a mere cultural experience became problematic in at least two ways: firstly, the extension of the grammatical expression found in the biblical Hebrew exemplars becomes conventionalised in such a way that the original construal no longer constrains how the biblical Hebrew speakers think about the experience; and secondly, this released consequence influences recent publications on heaven. Consequently, most modern publications on heaven construed heaven as a relative design. This study argues that such inhibited way of expressing heaven reduces the structural schematisation as construed in the Hebrew Bible. Methodologically, this study proposes an experientialist-embodied approach towards the conceptualisation of heaven. The result, in theory, is a more effective schematisation in which different semantic structures were employed to express the experience. This is then applied towards understanding the spatial image schema of up versus down in the Hebrew Bible and offers a vantage point from which to investigate the whole network of the biblical Hebrew spatial cognition.

CONTRIBUTION: This article contributes to the understanding of the ancient Israelite conceptual system for 'heaven' in the Hebrew Bible

Keywords: ancient Israelite; heaven; conceptual system; spatial cognition; biblical Hebrew.

Introduction

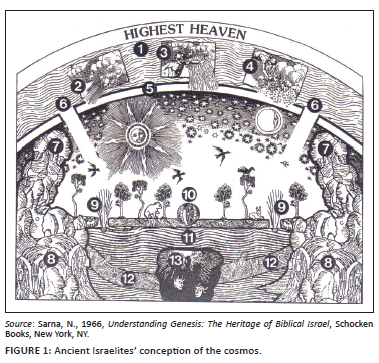

In their work on the biblical conception of the cosmos, Sarna (1966), Schwegler (1960), Matthews and Benjamin (1991), Keel and Uehlinger (1990) and Cornelius (1994:193-218, 1998:217-230) summarise some of the pertinent aspects of the cosmology of the ancient Near East. The point of departure for this multifaceted image was a literal approach to iconographic, archaeological and textual evidence and 'depended almost exclusively on the late Deuteronomistic statements about the contents of the heavenly realm' (Wright 2000:92).

The traditional biblical conception of the cosmos and consequently the traditional argument that to the ancient Israelite mind, 'space' was 'merely an accidental set of concrete orientations, a more or less ordered multitude of local directions and each associated with certain emotional reminiscences' (Jammer 1954:7-8), Houtman (1974:195-219), Deist (1987:1-17) and Cornelius (1994:193-218, 1998:217-230) to argue that the Israelites did not have a 'cosmology' in the sense of a generally accepted concept of the structure and order of the cosmos. Stadelmann (1970:143) summarises this philosophy of scholars about the biblical conception with the following words: 'The spatiality of the world was intelligible to the ancient Israelites to the degree that they were able to describe it in terms of concrete images'. Therefore, it is argued that the 'picture' of the three-tiered structure of the world (Figure 1) depicted in the Hebrew Bible has its roots not only in the basic human experience of the external world but also in the mythological traditions cherished among their neighbours (ed. Beyerlin 1975:68-145; Stadelmann 1970:143; Walton 2006:186). This is evident in the Hebrew Bible as literature, as well as in the artistic expression in iconographic discoveries:

-

The water above the earth/firmament (cf. Gn 1:6; Ex 20:4)

-

The storehouse of the wind (Ps 135:7)

-

The storehouse of the snow (Job 38:22; Is 55:10)

-

The storehouse of the hail (Job 38:22)

-

The firmament (Gn 1:7)

-

The windows of heaven (Gn 7:11; 8:2)

-

The pillars/foundations of the heavens/firmament (2 Sm 22:8)

-

The pillars/foundations of the earth (Ps 82:5; Is 24:18)

-

The fountains of the deep (Gn 7:11; 8:2)

-

The centre of the earth (Ezk 38:12; Is 19:24)

-

The waters under the earth (Ex 20:4)

-

The rivers of the underworld (Ps 46:4; Jnh 2:3)

-

The underworld/Sheol (Jnh 2:2; Job 11:8; 17:16) (Deist 1987:1-17).

This schematic view of the three-tiered cosmos suggests that the constitutive elements of the cosmos stand towards one another in a structural relationship. Just as the earth (אֶרֶץ)(ʾæræṣ), resting on its pillars is linked with the underworld (שְׁאוֹל) (šeʾôl), so too, is heaven (שָׁמַיִם) (šāmayim), whose foundations are established upon the extreme parts of the earth. אֶרֶץ (ʾæræṣ) signifies the dwelling-place of humans or primarily the entire area in which humans think of themselves as living, distinct and opposed to the reigns of (שָׁמַיִם) (šāmayim) and (שְׁאוֹל) (šeʾôl) (see Walton 2006:166). However, for Stadelmann (1970:2, 8, 165), the Hebrew Bible does not distinguish container from contents, or, conversely, the living from its environment. Heaven, earth and underworld are thus not entities on their own, but interrelated and interconnected.

The whole of heaven, as is argued, is not pieced together out of its parts but is constructed from them as constitutive elements. The ancient Israelites' conception of שָׁמַיִם (šāmayim) represents an expression for location in space and comprises the upper world. If שָׁמַיִם (šāmayim) and אֶרֶץ (ʾæræṣ) are brought into relation with one another, they express the idea of totality (Stadelmann 1970:39-40; Walton 2006:168). The entire section of the cosmos which is above the earth includes the heaven as well as the 'air'. In the absence of a specific word for 'air' in the vocabulary of the Hebrew Bible, the space between heaven and earth was designated by the expression 'between the heaven and between the earth' (בֵּין הָשָּׁמַיִם וּבֵין הָאָרֶץ) (beyn hāššāmayim ôbeyn hāʾāræṣ) (2 Sm 18:9).

The lifelike view of cosmic divisions seems partly to be overcome by a perspective, which transcends the horizon of humans. Thus, the vertical direction from earth to heaven prompted the idea, in intentional order of motion towards heaven. The movement expressed by הָשָּׁמַיְמָה (hāššāmaymāh) (Ex 9:8) designates motion towards heaven. When the Hebrew Bible uses the term הָשָּׁמַיְמָה (hāššāmaymāh), which is only a spatial term and as such is limited in its meaning, it did not intend to formulate a theory of a dynamic universe as contrasted with the Eleatic assertion that the universe is inert, static, finished and complete (Stadelmann 1970:39-42).

So, it appears as if שָׁמַיִם (šāmayim) designates the space above the אֶרֶץ (ʾæræṣ), including the atmosphere, the region of the clouds, the heavenly vault, the firmament and that which exists above the firmament. This space was not conceived as a structured complex of clearly distinguishable levels as, for example, in Rabbinical and Babylonian literature (Stadelmann 1970:41). The genitive expression שְׁמֵי הָשָּׁמַיִם (šemey hāššāmayim) occurs in poetry (Ps 148:4), in prayers (1 Ki 8: 27), in Moses' address to the people (Dt 10:4) and in the message of Solomon to king Hiram (2 Chr 2:5). The use of שְׁמֵי הָשָּׁמַיִם (šemey hāššāmayim) (literally: 'heavens of the heaven') in these texts indicates that the expression belonged to the elevated language style, implying an intensification of the idea of heaven: highest heaven. Furthermore, as those texts illustrate, שְׁמֵי הָשָּׁמַיִם (šemey hāššāmayim) never represented the abode of God, since 'the highest heaven cannot contain (God)' (1 Ki 8:27) (Stadelmann 1970:41-42). The vast surface of the earth is represented as a garment spread out from horizon to horizon. The edge of this garment appropriately represents the boundaries of the earth, which enclose and confine it. These boundaries are known as קַצְוֵי הָאָרֶץ (qaṣwey hāʾāræṣ) 'borders (i.e. boundaries) of the earth'. The noun קָצֶה (qaṣæh) ('end'/'edge') is in the same semantic domain of the verb קָצֶה (q-ṣ-h) 'to cut off' and became a kind of spatial expression for the boundaries of the earth.

Hitherto, it seems as if the picture of the three-tiered structure of the cosmos derived within a traditional biblical scholarship's spatial understanding in the Hebrew Bible has its roots in the following one or two aspects, or a combination thereof, namely, the basic human experience of the external cosmos from whose impressions humans conceived such an imaginative depiction and in the mythological traditions so exquisite among the ancient Israelites (for a summary of these mythological traditions, see ed. Beyerlin 1975:68-145; Cassirer 1946:298-303; Stadelmann 1970:54-56; Walton 2006). However, concerning the picture of the heavenly realm in the Hebrew Bible, Wright (2001:72-75) argued that the biblical editors did not create a record of the entire spectrum of ancient Israel's religious beliefs and practices, and that the biblical image and the ancient Israelite's image of the heavenly realm, differ.

Problem statement and hypothesis

The traditional biblical scholarship's conception of the cosmos and consequently the traditional biblical scholarship's argument that to the ancient Israelite's mind, 'space' was 'merely an accidental set of concrete orientations, a more or less ordered multitude of local directions and each associated with certain emotional reminiscences' (Jammer 1954:7-8) is problematic in the definition of cognitive models. Moreover, the traditional view reflected in biblical Hebrew dictionaries and textbooks that heaven is construed in a non-experiential way became problematic in at least two ways: firstly, the extension of the grammatical expression found in the biblical Hebrew exemplars becomes conventionalised in such a way that the original construal no longer prescribes how the biblical Hebrew speakers think about the perceptual experience; secondly, this declared consequence influences recent publications on heaven. Consequently, most modern publications on heaven construe heaven as a relative design (see e.g. Johnston 2002; Wright 2000).

The following section of this study argues that such an inhibited way of expressing שָׁמַיִם (šāmayim) reduces the structural schematisation as construed in the Hebrew Bible. It proposes an experientialist-embodied approach towards the conceptualisation of heaven. The result, in theory, is a more effective schematisation. The outcome may be helpful to understand different metaphorical expressions and spatial image schemas in the Hebrew Bible and offers a vantage point from which to investigate the main part of the network of the biblical Hebrew spatial cognition.

A frame-semantic approach towards the conceptualisation of heaven

Cognitive semantics holds that the semantic process of linguistic expressions (such as 'going up to heaven') is fundamentally based on bodily experience (Lakoff 1987). Semantic knowledge is thus constituted by what we experience in life, and its structure is determined by how we experience things in life. In other words, the semantic process involves the activation of the relevant semantic elements and also the structure determined by the semantic knowledge.

The knowledge structure of שָׁמַיִם (šāmayim) comprise schematisations of the ancient Israelite's experiences of space, whether sensorimotor or subjective. Memories of similar and related components become organised into a system of perceptual symbols (schematic memories), which exhibit coherence. This perceptual symbol is referred to in the experiential strategy as a frame. A frame is an information structure consisting of large collections of perceptual symbols, encoding information which is stable over time as well as incorporating variability (see Evans 2009:179; Lamprecht 2015:42-48). So, frames are idealised or schematised in several ways. One way is that, often, what the frame defines does not actually exist in the world. Kövecses (2006:65) gives the following example to explain the property: 'there are no seven-day weeks in nature. In nature, humans only find the alternation of light and darkness governed by the natural cycle of the movement of the sun'. Frames are often idealised in this sense. Lakoff (1987) called such idealisations 'idealized cognitive models' (ICMs). An important consequence is that this feature of frames makes frames open to cross-cultural variation. Hence, a frame provides a unified, and, therefore, coherent, representation of a particular entity.

Biblical Hebrew - as indeed every other language - has a semantic structure of its own (Ullendorff 1977:66). The semantic structure reveals the mental approach and attitudes of the speakers in respect to what they observed in their daily lives, that is perceptual experiences with an everyday knowledge representation. The original concept or original construal of heaven thus would only make sense in the frame of a culture where it is common to ascribe the inexplicable meteorological activities in the sky in relation to a divine sphere. Thus, a word concept such as 'heaven' cannot be understood apart from the intentions of the participants or the social and cultural institutions and behaviour in which the action, state or thing is situated (see also Croft & Cruse 2004:11). Neither can we understand how the spoken sounds שָׁמַיִם (šāmayim) can become the vehicle of a purely intellectual meaning. This is only understandable if we assume that the basic function of meaning is present and active before the individual sign is produced. The function of meaning includes the construction of form and meaning, or in other words, the expression of thoughts and ideas (see also Evans & Green 2006:6).

Spatial intuition begins to acquire a systematic structure: If one were required to describe the concept heaven, one might be tempted to seek the common characteristics of all attributes and values related to heaven. In the following part the structures of the heaven frame describing the ancient Israelites' experience of spatiality, heavenly bodies, spatial colour phenomena and the natural inhabitants of space will be discussed.

Structure of the heaven-frame

'Heaven is … a place on earth' (the theme of a well-known and popular song in the 1980s by Belinda Carlisle), '-… a place where you are happy' (the title of a book by Barbara Walters), '-… so real' (the title of a recent publication of Choo Thomas) - expressions such as these illustrate to what extent heaven as concept has informed the popular imagination.

Nevertheless, the understanding of such modern viewpoints is construed by a relatively antonymous construct, that is happy versus sad, as hybrid opposition, that is real versus unreal, etc. and is merely a transferred or extended abstract of the original symbol. Even in religious literature the stance is the same, as concepts of heaven formed in Christianity are 'Kingdom of God' (Mk 9:46), 'Garden of Eden', 'Paradise' (2 Cor 12:4), 'New Jerusalem' and 'Pearly gates'; in Jewish religion heaven is 'Gan Eden' ('garden of Eden') and 'Olam Haba' ('world to come') and in Islamic religion heaven is 'Jannah' ('paradise') (Masumian 2002:28, 56, 73). Thus, different images were employed to structure the same basic conceptual content. From this the perception derives that any attempt to form the concept of heaven by abstraction is practically the same as looking for the glasses on your nose, with the help of the same glasses.

Hence, it seems as if a literal construal 'heaven is a place' (an idea existed in some early religions) and a gradable figurative construal 'heaven is a better place' in contemporary religious literature (Tibetan Buddhism) becomes the normal or even the only way to talk about the experience behind the concept, heaven. Such extended constructions may be applicable to the experience, but in this study the hypothesis is accepted that the extensions for the concept heaven found in traditional encyclopedias (eds. Botterweck & Ringgren 1982; Gesenius [1810-1812] 2008; ed. Holladay 1988:375; eds. Jenni & Westermann 1971:1369-1372; Koehler & Baumgartner 1958:986) and in recent publications on heaven (see e.g. Wright 2000) are incompatible with the original construal in the Hebrew Bible. This hypothesis is grounded in one of Croft's (2000) assumptions on construal operations, which is applied to biblical Hebrew, namely that it may be that the extension of the lexical expression 'heaven' found in the biblical Hebrew examples becomes conventionalised in such a way that the original construal no longer prescribes how the biblical Hebrew speakers might have thought about the experience.

Subsequent to this assumption, a promising explanation for the lexical item 'heaven' includes in its semantic specification information relating to the degree of extension (Evans & Green 2006:195-196). For example, part of the meaning of heaven is schematic, relating to the degree of extension associated with the firmament. The rich encyclopaedic meaning associated with the lexical item heaven relates to its specific properties as an entity involving colour, height and luminaries. In contrast to this rich and detailed specific meaning, its schematic meaning concerns the degree of extension associated with this entity. The schematic category 'degree of extension' has two values: a bounded extent and an unbounded extent. Heaven is typically bounded within the perceptual field of a human experiencing his or her first glimpse of the horizon. Then again, the unbounded extension is more complicated: in view of astrophysical evidence, the expanse has no beginning and no end and is thus, unbounded, while our 'real' experiences of the expanse reflect the same view - we can see neither the deep end nor the three-dimensional surface of our selected expression 'under the sky', which is reduced by scalar adjustment.

The reason for the different abstract and extended images that are employed to structure the same basic conceptual content of heaven is probably cited in the absence of a schematic meaning-register in dictionaries. While a schematic meaning-register includes 'heaven' as a 'superordinate concept, one which specifies the basic outline common to several, or many, more-specific concepts' (Tuggy 2010:82), dictionaries instead only represent the encyclopaedic meaning, which is merely culture-based (see Houtman 1993:7). The schematic meaning involving bodily experience lacks information. The traditional Hebrew dictionaries (eds. Botterweck & Ringgren 1982; Gesenius [1810-1812] 2008; ed. Holladay 1988:375; eds. Jenni & Westermann 1971:1369-1372; Koehler & Baumgartner 1958:986) usually contain only some degree of semantic analysis, but a structural semantic and contextual analysis is lacking. Thus, the aim of this section of the study is not to explain the meaning of the word heaven but to elaborate on the concept involved by acknowledging the schematic meaning of heaven. This study is, therefore, motivated to explore the given issues by the drive to understand the ancient Israelite's spatial cognition and the role bodily experience plays therein. In advance, however, Barr (1992:143) suggested that 'the semantic analysis of the older dictionaries seems often to be defective and needs to be rethought'.

Within the framework of cognitive models, the emphasis is upon relating the systematicity exhibited by language directly to the way the mind is patterned and structured, and in particular to conceptual structure and organisation.

Structural schematisations of heaven in the Hebrew Bible

Experience of spatiality

As a radius can only be defined relative to the structure of a circle (Croft & Cruse 2004:14-15), so can heaven only be defined relative to the tripartite structure of heaven - earth - sheol. Thus, one can understand heaven in the Hebrew Bible only against a background of understanding the ancient Near Eastern world picture (Figure 1). Along with this tripartite structure, the experience of physical buildings with a foundation, a roof, windows, doors and city structures with a gate and pillars (see ed. Beck 2011:94-95, 104-106, 211, 265) must have been deeply rooted when construing the abstract concept of heaven metaphorically.

The structure of heaven is well-attested in the Hebrew Bible. In Job 22:14, heaven is metaphorically described as 'the vaulted heavens'. Among others we find the architectural metaphors pertaining to its construction the 'gate' (Gn 28:17), the 'doors of heaven' (Ps 78:23), the 'windows' through which rain (Gn 7:11; 8:2), food (2 Ki 7:2, 19), manna (Ps 78:23-24) or blessings (Ml 3:10) came down, the 'foundations of heaven' (2 Sm 22:8) and the 'pillars of heaven' (Job 26:11). So, the ancient Israelites regarded heaven as the site of a building in which God dwells while the residence of God was provided with an עֲלִיּוֹת (ˊaliyyôt) 'upper or roof-chamber' (Ps 104:3).

Thus, it seems that the frame structure was constructed as an experiential construal in understanding the concept of heaven. The comparison between the source domain structure and the target domain heaven represented the metaphor heaven is a structure (Lakoff & Johnson 1980). The 'structure' is construed relative to the human's canonical upright orientation, and therefore heaven can also be seen as up. The metaphor heaven is up would then be applicable to the experience. The following derivation can thus be made:

-

Heaven is up construes the trait as relational and introduces a degree of separation between the distant trait and the person on earth. One can ascend to heaven, at least theoretically (Ps 139:8; Job 20:6; Pr 30:4). Heaven is thus approachable, but inaccessible for the human being. This, together with the 'real' experience of heaven as unbounded (no deep end and a three-dimensional surface), further implies that heaven is not measurable (no small and big heaven) and probably accounts for the grammatical majestatis pluralis form of the word.

Experience of heavenly bodies

The sun by day, the moon by night and the stars by night are explicitly associated with the concept of heaven (Gn 1:3-5, 16). The relation between what the heavenly bodies are and the place in which they are situated is not purely external and accidental; the place itself is part of those heavenly bodies, conferring upon them very specific inner ties. Such a relationship is still reflected in the diverse significance of צְבָא הָשָּׁמַיִם (ṣebāʾ hāššāmayim), understood as 'army of heavenly bodies' (Dt 4:19; 2 Ki 21:3; Jr 8:2). The heavenly bodies are placed in the same class as humans and animals, and this is the clearest confirmation that the ancient Israelites thought of them as beings which move with energy of their own, endowed with personality and were probably the guides of human destinies from above (Cassirer 1946:300; Walton 2006:103-105, 179-181). Thus, heaven held a special connection with the supernatural and referred to a divine sphere. The ancient Israelites shared the view that the star-strewn sky at night, as well as the cloudless blue sky by day, with its unobstructed light, is the divine prototype of purity (Ex 24:10). Therefore, 'heaven' became the basis for the conception of the dwelling place of the heavenly beings (Stadelmann 1970:54).

The genitive construction or phrase 'the God of heaven' appears nine times in the Hebrew Bible. Subsequently, the heavens are often referred to as God's heavens (Ps 115:16; Lm 3:66). He is the possessor. This view is explainable within the experience of earthly kingdoms. A king or queen can only be a king or queen if he or she possesses physical land and if he or she is alive and present in this kingdom. A king usually lived in a palace and 'ruled' from his throne. His commands had to be obeyed by everyone in his kingdom. Heaven is thus not only God's possession, but heaven must be God's dwelling-place (Dt 26:15; 2 Chr 30:27) as well. He built his lofty palace in heaven (Am 9:6). Heaven is also the location of God's throne (Ps 2:4; 11:4; 103:19; 123:1). He was not simply in heaven, but he was high in the heavens (Job 22:12). God's word is eternal and stands firm in the heavens (Ps 119:89). As experienced as a being with personality, God looks (Ps 33:13) and looks down (Dt 26:15), speaks (Ex 20:22; Neh 9:13), listens (1 Ki 8:30; 2 Chr 6:21) and answers (Ps 20:6-7) from or in heaven. As heaven is God's dwelling place, by a metonymy שָׁמַיִם (šāmayim) came to be used for God himself (Dn 4:23). This became a general practice among the Jews after the Maccabean period because of a religious scruple against using the divine name (Stadelmann 1970:55).

The understanding of the heavenly bodies as beings with personality conceptualises the frame divine sphere as an experiential construal in understanding the concept of heaven. The comparison between the source domain divine sphere and the target domain heaven represented the metaphor heaven is a divine sphere (Lakoff & Johnson 1980). The plurality of the 'divine heavenly bodies' in the 'sphere' implies the presence of a Ruler God. A government must be in possession of land, and, therefore, heaven can also be seen as a possession of this Ruler God. The metaphor heaven is a possession of God would then be applicable to this experience. Thus, the following derivation can be made:

-

If heaven is a divine sphere and heaven is a possession of God, then by experiencing heaven, you experience God's presence.

Experience of spatial colour phenomena

Light and darkness

Heaven reflects typically, within the perceptual field of a human experiencer, a variety of colours - blue at day, black at night, brown, with full moon at night and red and/or orange at sunset or sunrise. It is, however, the degree of extension of light and darkness that plays an essential role in ascribing the inexplicable meteorological activities in the sky in relation to a divine sphere. In contrast to the experience of a rich and detailed specific colour meaning, the schematic meaning [judging] concerns the degree of extension associated with the colour entity. God made the lights as signs to mark seasons and days and years (Gn 1:14), but warned Israel not to learn the pagan practices and 'be terrified by signs in the sky' (Jr 10:2), for 'those who divide the heavens', who gaze at the stars (Is 47:13) will be burned like stubble. God's judgement will take place by covering the heavens, by darkening their stars and the shining lights (Ezk 32:7-8), and by clothing the sky with darkness (Is 50:3). God will also destroy the disobedient by making the sky 'like iron/bronze' (Lv 26:19b; Dt 28:23). Darkness of the sky often goes side by side with the desolation of the earth - God will judge humans from heaven for their moral and immoral behaviour (Jr 4:23, 28).

It seems thus that the frame [judging] was constructed as experiential in understanding the concept 'heaven'. The comparison between the source domain judge and the target domain heaven represented the metaphor heaven is a judge (Lakoff & Johnson 1980). The 'judging action' implies righteousness, and, therefore, heaven can also be seen as righteous. The metaphor heaven is righteous would then be synonymous to the metaphor heaven is a judge. The following derivation can thus be made:

-

If heaven is a possession of God and heaven is a judge, then God is a judge.

-

If heaven is righteous, then it must be inhabited by all that are righteous.

Experience of the natural inhabitants of heaven

As a result of limited rainfall in Israel, water storage for daily survival, harvesting and ritual purposes was essential. Archaeology has shown that in almost every city a highly effective storage system was in use. Containers such as caves, chambers or vessels were commonly used. From the experience that important liquids were stored, heaven as a container appears in relation to all natural phenomena at and from heaven (Deist 2000:181). The waters in heaven have several forms: rain, dew, snow, etc., which came down from heaven as a blessing. So, dew was experienced as the 'gift of heaven' (Dt 33:13, 28, Hg 1:10; Zch 8:12) (see also ed. Beck 2011:64-65). Rain is the most common form of water and comes down (2 Sm 21:10) from 'the heavens, the storehouse' of God's bounty (Dt 28:12) and from the water jars of the heavens (Job 38:37). The wind also came forth from the storehouses (Jr 10:13).

It is thus evident that the schema [container] was constructed as an experiential construal in understanding the concept of heaven. The comparison between the source domain container and the target domain 'heaven' represented the metaphor heaven is a container (Lakoff & Johnson 1980). It is furthermore evident that the contents of this container were experienced as a 'blessing' and a 'gift'. The metaphor heaven is a possessor of good would also be applicable to the experience. The following derivations can thus be made:

-

If heaven is a possession of God and a possessor of good, then God is good.

-

Heaven construes all good for humans. Because heaven construes all the good which came down unto humans, good is up.

-

If heaven is up and a possessor of good, then good is up.

-

If God is good and good is up, then God is up.

-

If heaven is righteous and heaven is a container, then heaven must contain all that is righteous.

Thus, it is evident that the ancient Israelites' conception of heaven depended on their perception of space and their actions in space.

The frame heaven is full of meaning conferred upon it by the totality of humans' experience. It consists of sets of attributes and values. The attributes concern the aspects of the given frame, that is spatiality, structure, container, colour and inhabitants, while the values are the specification of those aspects. Heaven is thus experientially construed as an abstract mass, bounded and unbounded, with a righteous possessor, a possession of good and the embodiment of permanence (Ps 89:29) in a semantic schematisation (Figure 2).

So, the ancient Israelites' everyday concept of heaven is not 'culturally neutral' or a manipulation of abstract symbols. The heaven frame rather embodies different conceptualisations or cultural schemas (see also Van Steenbergen 2003:309). This implies that the experiential worlds with which we as human beings interact are more than simply physical. We are born into cultural milieu that influence and transcend our individual bodies and minds in time. This 'extended embodiment' does not exist in a vacuum: it is not, as it were, a property of the objects 'in them'. Rather, it is constituted and exemplified by the participation of the universe in an entire matrix of cultural practices, some of which are non-linguistic practices and some of which are linguistic. Furthermore, the perceptual analysis process enables perceptual information to be re-analysed so that a new kind of information is abstracted. In this concept formation the abstract ideas were regarded in the manner of living entities with resultant implications. This suggested the way in which such ideas were understood by the Hebrew speaker. The knowledge of the ideas became 'conceptual tools that reflect a society's past experience of doing and thinking about things in certain ways' (Wierzbicka 1997:5-6). Therefore, the world is presented in a kaleidoscopic flux of impressions, which have to be organised by our minds - and this means largely by the linguistic systems in our minds. In other words, humans 'translate' their thoughts into language.

Conclusion

This study has indicated that sensory systems recruiting information relating to the external environment and the ancient Israelites' interaction with the environment, shaped perceptual symbols of spatial associations, while using information relating to the motor aspects of the ancient Israelites' own bodily functioning, the ancient Israelites' subjective experience and culturally mediated conceptual schemes (see also the studies of Lamprecht 2021, 2022). These perceptual symbols form concepts that are organised within the conceptual system to provide larger-scale knowledge structures. In this way a new kind of information is abstracted. The author has proposed that one of the knowledge structures used by the ancient Israelites was the heaven frame.

The traditional argument that to the ancient Israelite's mind, 'space' was merely an accidental set of concrete orientations and consequently that heaven was construed in a non-experiential way, was challenged in terms of experiential abstract knowledge systems, that is the idealisation or schematisation of heaven as a frame. The particular symbol 'heaven' is full of meaning conferred upon it by the totality of human's experience. Therefore, heaven is experientially construed as an abstract mass, bounded and unbounded with a righteous possessor, a possession of good and the embodiment of permanence in a semantic schematisation. So, heaven was experientially construed in terms of: spatiality, container, structure, colour and inhabitants. Thus, it is evident that the Mediterranean peoples' conception of heaven depended on their perception of space and their actions in it.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on part of the author's PhD thesis on Spatial Cognition and the Death Metaphor in the Hebrew Bible.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationship that may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

Author's contributions

A.L. is the sole author of this research article.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards of research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Barr, J., 1992, 'Hebrew lexicography: Informal thoughts', in W.R. Bodine (ed.), Linguistics and biblical Hebrew, pp. 137-151, Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake, IN. [ Links ]

Beck, J.A. (ed.), 2011, Dictionary of biblical imagery, Zondervan, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Beyerlin, W. (ed.), 1975, Near Eastern religious texts relating to the Old Testament, SCM Press, London. [ Links ]

Botterweck, G.J. & Ringgren, H. (eds.), 1982, Theological dictionary of the Old Testament, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Cassirer, E., 1946, Language and myth, transl. K.L. Suzanne, Dover, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Cornelius, I., 1994, 'The visual representation of the world in the ancient near East and the Hebrew Bible', Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages 20(2), 193-218. [ Links ]

Cornelius, I., 1998, 'How maps "lie" - Some remarks on the ideology of ancient Near Eastern and "scriptural" maps', Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages 24(1), 217-230. [ Links ]

Croft, W., 2000, Radical construction grammar: Syntactic theory in typological perspective, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Croft, W. & Cruse, D.A., 2004, Cognitive linguistics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Deist, F.E., 1987, 'Genesis 1:1-2:4a: World view and world picture', Scriptura 22, 1-17. [ Links ]

Deist, F.E., 2000, The material culture of the Bible: An introduction, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Evans, V., 2009, How words mean, lexical concepts, cognitive models, and meaning construction, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Evans, V. & Green, M., 2006, Cognitive linguistics, an introduction, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, London. [ Links ]

Holladay, W.L. (ed.), 1988, A concise Hebrew and Aramaic lexicon of the Old Testament, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Houtman, C., 1974, De hemel in het Oude Testament, Wever, Franeker. [ Links ]

Houtman, C., 1993, 'Der Himmel im Alten Testament, Israels Weltbild und Weltanschauung', Oudtestamentische Studiën, vol. XXX, E.J. Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Jammer, M., 1954, Concepts of space: The history of theories of space in physics, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. [ Links ]

Jenni, E. & Westermann, C. (eds.), 1971, Theologisches Handwörterbuch zum Alten Testament, Kaiser Verlag, München. [ Links ]

Johnston, P.S., 2002, Shades of sheol: Death and afterlife in the Old Testament, Intervarsity Press, Westmont, IL. [ Links ]

Keel, O. & Uehlinger, C., 1990, Altorientalische Miniaturkunst, Philipp von Zabern Verlag, Mainz. [ Links ]

Koehler, L. & Baumgartner, W., 1958, Lexicon in Veteris Testamenti libros, E.J. Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Kövecses, Z., 2006, Language, mind and culture: A practical introduction, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Lakoff, G., 1987, Women, fire and dangerous things: What categories reveal about the mind, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. [ Links ]

Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M., 1980, Metaphors we live by, Chicago University Press, Chicago, IL. [ Links ]

Lamprecht, A., 2015, 'Spatial cognition and the death metaphor in the Hebrew Bible', PhD thesis, University of the Free State. [ Links ]

Lamprecht, A., 2021, 'The journey of Jephthah's daughter: On spatial cognition, body and language in Judges 11:37', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 77(1), a6888. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v77i1.6888 [ Links ]

Lamprecht, A., 2022, 'Ascending to Jerusalem: On spatial cognition, ideology and language in the Hebrew Bible', Journal for Semitic Studies, forthcoming. [ Links ]

Masumian, F., 2002, Life after death: A study of the afterlife in world religions, Kalimat Press, Los Angeles, CA. [ Links ]

Matthews, V.H. & Benjamin, D.C., 1991, Old Testament parallels: Laws and stories from the ancient Near East, Paulist Press, Mahwah, NJ. [ Links ]

Sarna, N., 1966, Understanding Genesis: The heritage of biblical Israel, Schocken Books, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Schwegler, T., 1960, Probleme der biblischen Urgesschichte, Räber, Munich. [ Links ]

Stadelmann, L.I.J., 1970, The Hebrew conception of the world, Pontifical Biblical Institute, Rome. [ Links ]

Tuggy, D., 2010, 'Schematicity', in D. Geeraerts & H. Cuyckens (eds.), The Oxford handbook of cognitive linguistics, pp. 82-116, Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Ullendorff, E., 1977, Is biblical Hebrew a language? Studies in Semitic languages and civilizations, Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden. [ Links ]

Van Steenbergen, G.J., 2003, 'Hebrew lexicography and worldview: A survey of some lexicons', Journal for Semitics 12, 268-313. [ Links ]

Walton, J.H., 2006, Ancient Near Eastern thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the conceptual world of the Hebrew Bible, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Wierzbicka, A., 1997, Understanding cultures through their key words, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Wright, J.E., 2000, The early history of heaven, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Wright, J.E., 2001, 'Biblical versus Israelite images of the heavenly realm', Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 93, 59-75. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Adriaan Lamprecht

at.lamprecht@nwu.ac.za

Received: 13 May 2022

Accepted: 24 July 2022

Published: 07 Sept. 2022