Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.31 n.1 Pretoria 2018

https://doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2018/v31n1a10

ARTICLES

Breaking of a new day in Job 38:12-15

Aron Pinker

Independent, USA

ABSTRACT

Exegetes usually approach vv. 12-15 from two different perspectives: the cosmological and the terrestrial. Some believe that the strophe alludes to astronomical bodies, which are visible in the morning and fade as the light brightens. Most view the strophe as describing the breaking of a new day, and the effect that the growing illumination has on the visibility of Earth's features and the activity of the wicked upon it. In this approach wickedness is unrealistically considered to be perpetrated mainly at night and the day is implicitly described as being an idyllic time. Worse, it presents God as being ineffectual in his treatment of wickedness, since it has to be repeated every morning. Such an admission would hardly fit the majestic speeches of God.

This study proposes a new approach to vv. 12-15, which capitalizes on the possibility that the figure presented in these verses is that of an at dawn wake-up of a military encampment for an imminent battle. The military context presents God as the commander of the universe and makes the fundamental question in the strophe meaningful to Job, who as a chieftain probably had to lead his men to battle. The two basic elements in our strophe are "knowledge" and "advantageous utilization." God is effective because he can combine these two elements. Man can never be as effective as God, because his "knowledge" will always be inadequate.

Keywords: Job 38:12-15; morning; dawn; morning wake-up in military; military metaphors; military terminology; order of battle; phalanx; tactical advantage of timing; "sun advantage"

A INTRODUCTION

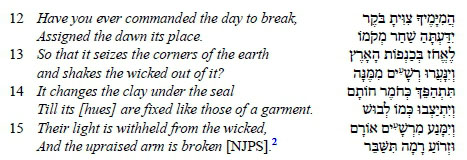

Job 38:12-15 is the third strophe in God's first response to Job (38:1-40:2). It appears after the strophe that describes the world's creation (vv. 4-7), and the strophe that deals with divine control of the unruly waters (vv. 8-10).1 The third strophe deals with God's description of the breaking of a new day on earth. It reads:

In Clines' view,

Though the Hebrew is not especially difficult, the meaning of this stanza is extremely problematic. … The strophe seems to be saying that when the morning has been given the command (v 12), it (or perhaps it is implied that God is the subject) takes hold of the edges of the earth and shakes it, as if to remove loose objects, which are apparently the "wicked" (v 13). The earth then, no doubt with the growing light in the sky, becomes more visible and increasingly three-dimensional, like the impression in a clay seal as light shines on it from an angle (v 14), while the light is kept from the wicked and their power is broken (v 15).3

A literal reading of our strophe confronts us with the manifest difficulties of v. 14. What does the metaphor in v. 14a refer to? Does a seal change the hues of the clay under it? How should we understand v. 14b? Clearly, as Clines says,

ויתיצבו "and they stand" is hard to fit into the context (KJV "and they stand as a garment" is not very intelligible). The plural is a difficulty, since there has been no plural since רשעים "wicked (?)" in v. 13, and one cannot see how they would be standing like a garment.4

Whybray finds in our strophe some Ugaritic mythological notions and an echo of the ordering of time in Gen 1:14-19.5 Andersen is frustrated by the repeated switches in allusions from line to line in the terrestrial approach. He says,

The traditional interpretation seems to describe the sunrise as a removal of the dark robes of night from the world, exposing the wicked, which had sheltered beneath the cover. But it in the last word refers to earth not to skirts. The imagery of v. 14 is quite different. The tinted rays of the early morning sun bring the earth's surface into sharp relief like soft clay under a seal. But the figure is lost in verse 14b, unless the color refers to the pink hues of dawn. But the mention of a garment and the return to the wicked in verse 15 suggests that we have picked up once more the theme that evil-doers are restrained by day light. The shattering of the arm upraised for violence (15b) hardly allows us to call the sun their light.6

Any literal understanding of vv. 12-15 raises some serious difficulties with the logical flow of events. Clines identifies the following problems:

(i) Thematic consistency - One would have expected this strophe to deal only with cosmological matters, as is the case in vv. 4-38, and not to involve human beings.

(ii) Moral language - The twofold mentioning of the "wicked" (רשעים) and the breaking of the upraised arm (וזרוע רמה תשבר) is surprising. Clines notes that "there is very little about humans in the whole of the Yahweh speeches, and even less about any moral government there may be of the world."7

(iii) Scribal abnormality - The ע of רשעים is written with abnormal elevation. This suggests to Clines some hesitancy on the part of earlier scribes as to the appropriateness of this word in context.

(iv) Cosmological and ethical interrelationship - It is not clear how the cosmological text in this strophe (vv. 12-13a, 14) is related to the ethical acts described in the rest of the text (vv. 13b and 15).

(v) Rare phrase - The phrase זרוע רמה is unique in the Tanakh. This suggests the possibility that it is not authentic.8

As we shall see in the following section additional difficulties can be identified.

The purpose of this study is to develop a new understanding of our strophe, which obviates the identified difficulties. Our approach draws on some tactical modalities of ancient warfare. It suggests that the figure presented in vv. 12-15 is that of an at dawn wake-up of a military encampment for an imminent battle. In this context, the fundamental question presented to Job in the strophe is of paramount importance for a commander from the tactical point of view, and would have been meaningful to Job, who as a chieftain probably had to lead his men to battle. The military context also alludes to God as the commander of the universe in possession of critical intelligence information.

In the following sections, translations/interpretations of vv. 12-15 by the ancient versions and a representative sample of modern exegesis will be considered. This analysis will illustrate the difficulties that the translators and exegetes faced with our strophe, how they tried to overcome them, and the weaknesses of these efforts. Finally, a new solution will be proposed and defended.

B ANALYSIS

In vv. 12-15 the Septuagint seems to be taking a cosmological/terrestrial approach; the Targum's concern is mostly terrestrial, and that of the alternative version is even focused specifically on Israel; the Peshitta and Vulgate have literal translations with a terrestrial focus. The Septuagint considers v. 14 and v. 15 as each being a separate question. Vulgate turns only v. 13 into a separate question.

1 Ancient versions

The Septuagint understands our strophe as referring to the creation of the stars and speaking humans. It renders vv. 12-15:

12Or did I order the morning light in thy time; and did the morning star then first see his appointed place; 13to lay hold of the extremities of the earth to cast out the ungodly out of it? 14Or didst thou take clay of the ground and form a living creature, and set it with the power of speech upon the earth? 15And hast thou removed light from the ungodly, and crashed the arm of the proud? (Ἢ ἐπὶ σοῦ συντέταχα φέγγος πρωϊνόν; Ἑωσφόρος δὲ εἶδε τὴν ἑυτοῦ τάξιν, ἐπιλαβέσθαι πτερύγων γῆς, ἐκτινάξαι ἀσεβεῖς ἐξ αὐτῆς; Ἢ σὺ λαβὼν γῆν πηλὸν, ἔπλασας ζῶον, καὶ λαλητὸν αὐτὸν ἔθου ἐπὶ γῆς; Ἀφεῖλεσ δὲ ἀπὸ ἀσεβῶν τὸ φῶς, βραχίονα δὲ ὑπερηφάνων συνέτριψας;).9

The Septuagint assumes that in v. 12 the term הֲמִיָּמֶיךָ = "have you, in thy time" (Ἢ ἐπὶ σοῦ), apparently reading הממך; reads instead of MT 2nd person (צִוִּיתָ) the 1st person צִוִּיתִי = "did I order" (συντέταχα), which does not agree with יִדַּעְתָּ in the parallel colon; adds to בֹּקֶר = "morning" (πρωϊνόν) the word "light" (φέγγος); reads instead of MT the pi'el of ידע (יִדַּעְתָּ) the qal יָדַעְתָּ = "did see" (εἶδε); takes וְיִנָּעֲרוּ = "to cast out, or shake out" (ἐκτινάξαι); takes בְּכַנְפוֹת = "of the extremities" (πτερύγων); תִּתְהַפֵּךְ כְּחֹמֶר = "take clay of the ground" (λαβὼν γῆν πηλὸν), paraphrasing; instead of MT חוֹתָם reads חַיָּתָם = "form a living creature" (ἔπλασας ζῶον); it is not clear how the Septuagint could derive from MT the translation "and set it with the power of speech upon the earth" (καὶ λαλητὸν αὐτὸν ἔθου ἐπὶ γῆς); וְיִמָּנַע ≠ "And hast thou removed" (Ἀφεῖλεσ δὲ); has אוֹרָם = "light" (τὸ φῶς); and, renders תִּשַּׁבֵּר = "crashed" (συνέτριψας).

The main Targum is literal, but the alternative expands somewhat on the MT.10 The two versions read:

Targum seem to be reading in v.12b לְשַׁחַר = "to the dawn" (לקרצתא). The variant of v. 12a is more specific with regard to מִיָּמֶיךָ = "Were you in the days of the beginning" (הביומי בראשית הויתא), turning v. 12a into a twofold question: "Were you in the days of the beginning and did you…?"; it reads לִהְיוֹת וְצִוִּיתָ בֹּקֶר = "and did you command the morning to be" (ופקדתא למהוי צפר); it is also reading in v.12b מְקֹמוֹ מהו= "what its place was" (האן אתריה). It takes in v. 13a בְּכַנְפוֹת = "of the borders" (בגדפי); וְיִנָּעֲרוּ = "and be shaken" (ויטלטלון). The variant of v. 13 has בְּכַנְפוֹת = "of the borders" (בסטרא); adds "of Israel" (דישראל); and adds "rows" (דרא).

In v. 14 Targum renders תִּתְהַפֵּךְ = "It changes" (מתהפכא), using the participle instead of the imperfect; reads חוֹתָמָם = "their seal" (חותמא דילהון), though it is difficult to imagine that the Targum refers to the wicked; has וְיִתְיַצְבוּ = "and they (the wicked?) are made to stand" (ואתעדתון); and translates לְבוּשׁ = "a dirty garment" (כסו זהים), perhaps reading instead of MT לְבוּשָׁה. On the other hand the alternative version has תִּתְהַפֵּךְ= "It changed" (אתהפכת); also reads חוֹתָמָם = "their seal" (חותמא דילהון), though it is difficult to imagine that the Targum refers to the wicked; instead of וְיִתְיַצְבוּ has the expansion "and they are not broken like their bodies in that their breath is not" (ולא איתבריאו כמו גושמהון בלא נשמתהון); and renders לְבוּשׁ = "an empty garment."

Finally, Targum understands in v. 15 that וְיִמָּנַע מִרְשָׁ עִ ים = "is hidden from the wicked" (ואתכסי מן רשיעיא); אוֹרָם = "The light of their breath" (נהור נשמתהון), adding נשמתהון; and וּזְרוֹעַ רָמָה תִּשַּׁבֵּר = "and the uplifted arm is broken" (ואדרע מרמא תתבר). The variant translation has וְיִמָּנַע מִרְשָׁ עִ ים = "Hidden from sinners" (ואתכסי מן חייביא); אוֹרָם = "And the light of the just" (נהוריהון דצדיקי), adding דצדיקי; and וּזְרוֹעַ רָמָה תִּשַּׁבֵּר = "and the arm of the proud is broken" (ואדרע דגיותניא אתברת).11

Peshitta renders our strophe (except of v. 14) literally. It has:

12Have you commanded the dawn since your days began; or do you know the place of the morning; 13That it might take hold of the ends of the earth that the wicked might be thrown out of it? 14So that their bodies would be turned into clay, and be thrown into a heap. 15The light of the sinners shall be withheld, and the arm of the arrogant shall be broken.12

Peshitta seems to be switching in 12a בקר and שחר, making the progression more logical. In 12b, instead of the pi'el יִדַּעְתָּ in the MT, which reflects authority, Peshitta uses the qal יָדַעְתָּ ("do you know," which reflects just knowledge, and removes the specification of location (מְקוֹמוֹ) reading instead (מָקוֹם = "the place"). In v. 13b, "be thrown out" does not adequately reflect וְיִנָּעֲרוּ. Peshitta reads in 14a ותתהפך and probably חַיָּתָם "their life" (גויתהון) instead MT "seal" interpreting its reading by "their bodies." This led it to view v. 14a as a metaphor for the perishing of the wicked "So that their bodies would be turned into clay." The Peshitta's "and be thrown into a heap" for v. 14b cannot be anchored in the MT. Finally, its rendition of v. 15 agrees fully with MT.

The Vulgate presents a literal translation of the MT. According to the Douay-Rheims translation into English, it reads:

12Didst thou since thy birth command the morning, and shew the dawning of the day its place? 13And didst thou hold the extremities of the earth shaking them, and hast thou shaken the ungodly out of it? 14The seal shall be restored as clay, and shall stand as a garment: 15From the wicked their light shall be taken away, and the high arm shall be broken. (12numquid post ortum tuum praecepisti diluculo et ostendisti aurorae locum suum. 13et tenuisti concutiens extrema terrae et excussisti impios ex ea. 14restituetur ut lutum signaculum et stabit sicut vestimentum. 15auferetur ab impiis lux sua et brachium excelsum confringetur).13

The Vulgate takes in v. 12 הֲמִיָּמֶיךָ = "Didst thou since thy birth" (numquid post ortum tuum), which adds unattested detail; and reads וידעת = "and shew" (et ostendisti). It reads in v. 13a וְהַאֲחַזְתָּ "And didst thou hold" (et tenuisti) instead of MT לאחז; adds "shaking them" (concutiens); takes בְּכַנְפוֹת = "extremities" (extrema); and, וְיִנָּעֲרוּ = "and hast thou shaken" (et excussisti). Vulgate's literal rendering of v. 14, "The seal shall be restored as clay, and shall stand as a garment," makes no sense in the strophic context. Finally, in v. 15 וְיִמָּנַע ≠ "take away" (auferetur) and אוֹרָם = "their light" (lux sua) is enigmatic.

It is obvious that the authors of the Versions struggled with the semantic issues and thematic coherence of the text before them. This is evident from the translations, the meanings assigned to some of the terms, and the resorting to paraphrases and expansions. While the main problem in our strophe seems to be the understanding of the logical flow of the strophic theme, early exegesis also ran into difficulties with the terms חותם and יתיצב in v. 14a, and understanding of the metaphors.

2 Modern exegesis: Cosmological perspective

Verses 12-15, being part of God's response to Job, refer specifically to God's creation of the morning. This cosmological event, however, does not refer to the recreation of the original creation as described in the first chapter of Genesis, but to the daily repetition of what was set in motion at creation of the World (v. 12a); i.e., the morning is not being recreated but it reoccurs.14 Direct reference to cosmology in our strophe can be noted only in v. 12. Still, a number of scholars perceived cosmological concept to dominate the strophe; finding additional cosmological allusions in the text, as well as connotations that draw on mythologies that were current in the ANE.

Fohrer sensed that our text has been influenced by the ancient Creation myths. He says:

In diesem Falle wird die Finsternis als eine Urmacht gedacht, wie sie in Gn 1, 2 gleicherweise mit der Urflut ferbunden ist. Ferner wird vorausgesetzt, daß sich die Schöpfung im kommen des Morgens täglich erneuert. Das entspricht der babylonischen Vorstellungswelt, nach der die gleichen Erscheinungen wie bei der einstmaligen Weltschöpfung und ihre jährlichen Erneuerung im Tageslauf wiederkehren. Denn »die Morgesonne durchbricht das Dunkel der Nacht und vertreibt alle bösen Geister. Jeder Morgen ist wiederum ein Abbild des Schöpfungsmorgens im kleinsten«.15

Perdue perceives our strophe as reflecting the Akkadian mythology about Shamash, who moved across the heavens during the day and below the earth in the underworld during the night, "symbolizing both the cycle of rebirth at sunrise in the east and death during its western entrance into the netherworld or cosmic sea in the evening."16 However, it is difficult to see how this perception would account for most of the text in our strophe.

Cornelius discusses the description of God in Job 38:12-15 by comparing it with "the iconography of the gods as found in the art repertoire of the Ancient Near East." In his view these sources should be included in the study of the Book of Job, because they bring us "into contact with the conceptual world or world of ideas lying behind the book."17 Indeed, being attuned to the notions that prevailed in the cultural world in which the manuscript has been written is obviously not only desirable but also very useful. Ideational connotations that the ancient reader would have made naturally might seem to the modern reader improper or forced in the absence of such background.

This is vividly clear from Cornelius' conclusion that

In Job 38 God is described as the Creator, the one who, like the sun deities of the Ancient Near East, has the prerogative of establishing order, but also salvation for the righteous by destroying the powers of chaos and unrighteousness.18

Still a modern commentator such as Clines finds that:

First, we would expect the strophe to concern only with cosmological matters, as does everything else in this first section (vv. 4-38) of the first divine speech, and not to involve humans. Secondly, the presence of the wicked is surprising, for there is very little about humans in the whole of the Yahve speeches, and even less about any moral government there may be of the world.19

Cornelius' study shows that reference to humans in such cosmological contexts is frequent in ANE iconography (cf. Amos 5:8-9).

G. R. Driver finds the reference to the "wicked" in our strophe so much out of place that he tries to interpret the entire strophe from a cosmological perspective. G. R. Driver says,

The sense of the passage is clear except on two points: what is the "wicked" doing here, where they seem quite out of place, and what can the "high arm" be? For this, if it denotes the arrogant conduct of the wicked, is equally out of place in a description of approaching dawn. The whole context argues some celestial phenomena connected with the dawn.20

G. R. Driver suggests that רשעים in v. 13 refers to the constellations Canis Major and Canis Minor, since the rising of Sirius was associated in the ANE with the dry, hot and sultry season which brings with it sickness and pestilence.21 It seems that G. R. Driver is aware that the association of the ethical רשעים with seasonal weather changes is rather tenuous. He suggests also an alternative cosmological connection, which rests on the possible metathesis of רשעים into שְׂעִרִים.22 In support of this emendation, it should be noted that in Arabic شِعْرَى "hairy one" is used for Canis Major and the dual شِعْرَيَانِ "two hairy ones" is used for Canis Major and Canis Minor.23 If this cosmological connection is assumed, v. 13 would read: "that it may grip the ends of the earth and the Dog-stars are shaken out of it." But this makes no sense, since the Dog-stars are not on Earth. NEB tried to circumvent this difficulty by rendering the feminine ממנה = ממקומו ("from its place"). Clines, who thinks that G. R. Driver is "on the right track," is forced to admit that

It is indeed not at all an obvious metaphor to have the stars shaken from the sky by the morning; yet it is hardly stranger than having the wicked shake from the earth like crumbs from a carpet.24

In that he is right. However, this admission, coupled with the impossible understanding of ממנה, means that NEB's and Clines' adoption of G. R. Driver's concept does not offer an exegetical improvement and might be inferior to the standard notions.

The cosmological interpretation that G. R. Driver proposes for v. 15 is also untenable. He finds in the term זרוע "arm" an allusion to "the arm of Leo." Indeed, in Arabic ذرَاعً is also an astronomical term; whether simply as "the arm" or as "the arm of Leo." It refers to α and β Geminorum, when it is called the "extended arm," and α and β Canis Minoris, when it is called the "contracted arm."25 G. R. Driver observes:

Now these stars are reasonably high up towards the zenith and clearly visible from December to February, the season when the sky is least obscured in Palestine; they coincide, too, almost entirely with the Navigator's Line, i.e. the line of the stars which he learns first of all to identify as the most distinct- Sirius (α Canis Majoris), Procyon (α Canis Minoris), Castor and Pollux (α and β Geminorum), extended like a bent arm across the sky from the horizon to the zenith.26

Making these astronomical assumptions leads to the following interpretation of v. 15: "and the light of the Dog-stars is withdrawn from it and the Navigator's Line is broken up."

G. R. Driver asks: "Is the conjecture too bold that the Hebrew poet's 'high arm' is this band of stars clearly visible to the naked eye?" In Gordis' view the answer is "Yes." He says that: " … this ingenious interpretation we do not find convincing."27 It seems that for the understanding of our strophe the more relevant question is whether the suggested interpretation makes sense in the biblical context? With respect to this question the following observations can be made:

(i) Even G. R. Driver realized that in his suggestion the Hebrew זרוע and the Arabic ذرَاعً are used in different senses. Arabic ذرَاعً describes certain stars as an "arm" extended from a constellation. Hebrew זרוע describes a line of stars as an "arm" extended across the skies.

(ii) It is difficult to imagine that the author of the Book of Job could have expected his readers to have the astronomical knowledge for appreciating readily the allusions to the Navigator's Line (clearly visible only from December to February).

(iii) One can accept that the light of stars in the Navigator's Line would appear to be dimming as the sun rises in the morning. However, it is difficult to comprehend why the author would use the term תשבר, which in association with זרוע is usually a symbol of the destruction of power (Job 31:22, Jer 48:25, Ezek 30:21, 22, 24, Ps 10:15, 37:17), for the description of this phenomenon when he could have used תחלש or תעלם.28

(iv) One might wonder why the author of the Book of Job would mix a constantly repeated astronomical phenomenon with an astronomical event that is clearly visible only from December to February.

(v) Why should Job be awed by the Navigator's Line, in particular?

The difficulties that have been noted with G. R. Driver's astronomical interpretation of our strophe at least partially explain why relatively few adopted it (NEB, REB, Clines).

3 Modern exegesis: Terrestrial perspective

Most modern exegetes in esse adopt a literal understanding of our strophe, often making use of 24:14-17, and assuming metaphoric expressions. In this approach wickedness is unrealistically perpetrated mainly at night and the day is implicitly described as being an idyllic time. Worse, it presents God as being ineffectual in his treatment of wickedness, since it has to be repeated every morning. Such an admission would hardly fit the majesty of God's speeches.

Among the earlier modern commentators, Arnheim renders our strophe:

12Wie? Hast du in deinen Lebtagen den Morgen entboten, angewiesen dem Frühroth seinen Platz, 13Anzufassen die Zipfel der Erde, daß abgeschüttelt warden die Freveler von ihr? 14Sie verwandelt sich wie Siegelton, und Alles steht da, wie in Kleidern. 15Und entzogen wird den Frevlern ihr Licht, und der gehobene Arm bricht ab.29

In his view, this strophe echoes vv. 24:13-17, where the wicked are described as those who shun the light (מרדי אור) and engage in murder, theft, and adultery under the cover of darkness. In v. 15 he understands אורם as being "the night light."30 This interpretation makes v. 13 incongruous with v. 15. If the wicked were shaken off the Earth at daybreak then v. 15 would be superfluous. Moreover, the colour of ancient seal-clay (Siegelton) was fixed; it did not change as the colour of light that imparts to the earth its seeming hue. Thus, it is difficult to imagine how the Earth could possibly change colour as seal-clay (Sie verwandelt sich wie Siegelton). Finally, what does the emended "und Alles steht da, wie in Kleidern" mean, and what is its significance? While the process of growing visibility is spectacular and colourful, it is not obvious what its practical utility for mankind is.

A similar translation is offered by Hengstenberg.31 He understands v. 13a as referring metaphorically to the illumination of the Earth from one end to the other end (daß sie erleuchte die Erde, von einem Ende bis zum andern).32 Verse 13b means to him that daylight curtails the nefarious activities of the wicked (sie bei Tagesanbruch sich in ihre Schlupswinkel zurückziehen und es nicht wagen, die Werke der Finsterniß zu begehen, cf. C. 24, 17).33 Such an assumption with respect to the activities of the wicked appears to be rather naïve. Moreover, in this case the wicked continue to stay on earth and vv. 13b and 15 lose their force, since the wicked could continue their activities next night, after a day of rest. Obviously, Hengstenberg imports into the MT far more than it can reasonably support.

Hengstenberg explains v. 14a as referring to the Earth which from a dark mass comes into sharp relief as the morning light grows (die Erde, …, die während der Finsterniß einer unförmlichen Masse glich, die Schönheit der Gestaltungen und Bildungen wieder erhält). He takes v. 14a as being a metaphor for this process. A clay item, as soon as it is stamped with a seal, attains accepted characteristics (wie die Siegelerde, sobald ihr der Sigelring ausgedrückt wird, ein bestimmtes Gepräge erhält). In his view, the difficult יתיצבו in v. 14b refers to בקר and שחר, which stand and beautify as a dress, as a wonderful splendid garb, which decorates the earth. One, however, wonders if the stamping with a seal is an obvious and adequate metaphor for day breaking. Moreover, Dillman and others have noted that in v. 14 "Subjekt kann nicht בקר und שחר sein (Schultens, Rosenmüller) weil es sich hier um die Wirkung des handelt."34 Furthermore, it is difficult to see how the short period of day breaking is attributed with the glory of a full day of sunshine. Finally, v. 12b would normally mean setting the spot where light would first occur. Neither בקר nor שחר could possibly stand in any sense.

Dillmann views vv. 12-15 as describing the daily introduction of the morning light and its effect on the night-enwrapped Earth. In v. 12 God mentions an act which He has executed since creation, and in v. 13 he provides its purpose. God's rhetorical question to Job exposes vividly his impotence and limitations.35 In Dillman's view the subject in v. 13 is השחר, though in this case the plural וינערו is somewhat awkward. He says,

Das Morgenroth fasst auf einmal die Säume oder Zipfel der Erde, diese selbst als einen ausgebreiteten Teppich gedacht, indem es mit urplötzlicher Schnelligkeit (Ps. 139, 9) sich über das Erdganze verbreitet, und durch jene Anfassung werden die Freveler von ihr abgeschüttelt d. h. wird bewirkt, dass die lichtscheuen Bösen, die im Dunkel der nacht ihr Wesen auf ihr getrieben, plötzlich unsichtbar warden (24,16f.), sei es sich versteckend, sei es gefangen.36

Dillmann continues to propagate an unrealistic image of the situation that is described in v. 12-13 and v. 15. He personifies שחר; reads the singular וינער instead of the plural וינערו; assumes that ינערו (abgeschüttelt) = "wird bewirkt" = "plötzlich unsichtbar warden"; and assumes that the wicked are dormant during the day. Would God have challenged Job with such perpetuation of wickedness and injustice? Would God have victoriously announced in v. 15 "The favored darkness of the wicked (אורם) was withdrawn from them and their high arm was broken!" knowing that night would follow day?

Dillmann sees vv. 14-15 as a further development of the purpose expressed in v. 13. Verse 14 expands the idea expressed in 13a and v. 15 expands the idea contained in v. 13b. He considers as the subject of יתיצבו "die Dinge auf der Erde, die durch die Aufprägung des Siegels entstandenen Formen: sie stellen sich dar dem Gewande gleich d. h. in mannigfaltigen Umrissen und Farben."37 Dillman seems to be suggesting that יתיצבו means "standout." This meaning is not attested to in the Tanakh, where the hitpa'el of יצב is "to set oneself, to take a stand." Moreover, if Dillmann is correct, one may wonder why the author used this term when he did not have to. He obviously could simply have said ויהיו כמו לבוש. Finally, Dillmann does not explain why two metaphors (חותם and לבוש) were necessary, and what their thematic significance in the confrontation between God and Job is.

Like Arnheim, also Dillman understands in v. 15 the term יִמָּנַע as "withdrawn (entzogen)," though in the Tanakh מנע = "withhold, hold back." He too takes אורם = "their night light" (Finsterniss) drawing on 24:17. This is somewhat odd since the author could have used חָשְׁכָּם, unless God engages here in irony.

Hufnagel believes that our strophe is focused on what happens to the wicked at daybreak. His concise and dramatic, but interpretative, translation of vv. 12-15 reads:

12Ward's, weil du lebst, Morgen auf deinen Befehl - Bestimtest du seine Stelle dem Morgenroth, 13Der Erde Enden zu fassen, Abzuschütteln ihre Freveler? 14Umzuformen wie Ton ihre Rott, Sie hinzustellen Heuchler? 15Zu entziehen dem Frevler sein Licht, Zu brechen den drohenden Arm?38

He seems to be taking every verse as a question and reading בימיך (weil du lebst); ההיה לפקודתך (Ward's, auf deinen Befehl); taking ידעת = "you determined" (Bestimtest du); כנפות = "ends" (Enden); reading לנער (Abzuschütteln); להפוך (Umzuformen); taking חותם = "its red"(?) (ihre Rott); reading להציב = "to put" (hinzustellen); taking לבוש = "as a hypocrite"(?) (Heuchler); and reading למנוע = "to withdraw" (Zu entziehen). These changes amount to a reconstruction of the MT. They highlight the challenges that our strophe has presented to exegetes.

In Budde's view our strophe presents to Job one question, which refers to a daily recurrence; not to an act of creation. He notes that "da v. 20. 31. 32 u. B. w. beweisen, dass abwechselnd mit dem Wissen Hiob's auch sein Können und Tun Gegenstand der Frage ist," and that as elsewhere in God's speeches (for instance, v. 11) "lässt sich bei der Sorglosigkeit in Dingen der Rechtschreibung, …, schwer entscheiden." Budde suggests that the subject of לאחז is assigned in a complicated manner: "לאחז könnte gerundivisch Hiob (d. i. Gott) zum Subjekt haben »dass du ergriffest«; aber nachdem sie entboten sind, treten Morgen und Morgenröte (beide sind eins) in die Tätigkeit ein."39

Budde finds that

Bemerkenswert genug ist hier freilich diese Berührung des ethischen Gebietes, aber sie geschieht wie selbst verständlich. Das geht im Grunde Gott gar nichts an, das besorgt die Morgenröte ihrer Natur gemäss.

This cavalier treatment of an anthropomorphic dawn and of the ethical elements in the strophe is somewhat dismissive. In v. 14a he rejects the notion that כחמר חותם refers to the red colour of the seal clay, and suggests: "Nicht däss sie rot werde wie dieser, sondern sich so auspräge, ist gemeint." Budde apparently takes ארץ as the subject of תתהפך, but notes that the subject of יתיצבו is missing.40

The difficulties of our strophe have forced Delitzsch to assume that there are two kinds of wicked people: those who sleep at night (v. 13) and those who are up at night working on their nefarious designs (v. 15). The fate of the "sleepers" at daybreak is that:

The dawn of the morning, spreading out from one point, takes hold of the carpet of the earth as it were by the edges, and shakes off from it the evil-doers, who had laid themselves to rest upon it the night before.41

On the other hand the "night-workers'" fate is that:

The sunrise deprives them, the enemies of light in the true sense (ch. xxiv. 13), of this light per antiphrasin, and the carrying out of their evil work, already prepared for, is frustrated.42

Thus, according to Delitzsch the wicked who did no evil during the night are "emptied" from the earth at daybreak, but the wicked who were busy with evil design and activity get another chance the following night.43 This makes no sense.

Delitzsch translates our strophe:

12Hast thou in thy life commanded a morning. Caused the dawn to know its place, 13That it may take hold of the ends of the earth, So that the evil-doers are shaken from it? 14That it changed like the clay of a signet-ring, and everything fashioneth itself as in a garment. 15Their light is removed from the evil-doers, and the out-stretched arm is broken.44

He seems to be reading בימיך = "in thy life"; taking יִדעת = "caused";45 בכנפות = "of the ends"; assuming that the copulative ו has the sense "so that"; תתהפך = "it changed," implying actual change; adding "And everything"; taking יתיצבו = "fashioneth itself"; reading בלבוש = "in a garment"; and, taking ימנע = "is removed," which is unattested. Delitzsch's taking these exegetical liberties, and his final untenable result is testimony to the challenges that our strophe presented to its interpreters.

Ewald's main contribution to the exegesis on our strophe is his emendation of יתיצבו. He says: "Instead of יתיצבו, which would have to be understood according to i. 6, ii. 1, יתיצבו must be read, or rather must be so understood (since it does not occur again in the poetical part of the book of Job, except in the later pieces xxxiii. 5, xli. 2) from وبض = בּוּק [= 'empty'], but وصف also is probably originally the same."46 This emendation somehow leads him to the translation of v. 14b by "its tips become light as a garment," which adds words and imagery to the MT He has also for v. 13b "and the wicked flee from it alarmed," giving ינערו an unattested meaning. Ewald further confuses matters by explaining that: "the earth changes its entire form as rapidly and easily as the seal-clay changes the forms which are impressed upon it, whilst its wings, or skirts, become shining like a garment."47

The most original approach to our strophe was presented by Duhm. He suggests that our strophe consists of two different units that were intermingled. The original unit dealing with the initial stages of the day consists of vv. 12, 13a, 14a, and into it was interspersed an alien (unfitting) unit consisting of vv. 13b, 14b, 15, which speaks about the wicked. The original unit reads: "Hast du seit deinem Dasein bestellt den Morgen, Dem Frührot angewiesen seine Stätte, Zu fassen den Saum der Erde, Dass sie sich wandelt wie in Siegelthon?" On the other hand, the alien unit reads: "Da warden abgeschüttelt von ihr die Freveler, Und stehen da wie zur Schande, Und es wird den Frevlern ihr Licht versagt, Und der erhobene Arm verschwindet."48 Clines felt that "The idea of Duhm, that two completely different strophes have been mistakenly combined, had a lot to recommend it."49 Obviously, if half of the MT were to be effectively deleted, many difficulties would also disappear.

How could such an intermingling of two unrelated units have occurred? Duhm suggests that the "alien unit" was originally written on the margin and in subsequent transcription of the manuscript it was included in the text. Unfortunately his explanation does not provide any reasonable insights into the motives for the unit's original creation. Dhorme observes that "There is not the slightest shadow of proof offered for this fantasy."50 Lack of supportive evidence diminishes significantly the value of Dhum's insight. Moreover, his use of "bestellt" for צוה weakens in v. 12 its commanding tenor. Also, in the "original unit" the purpose of the active "Zu fassen den Saum der Erde" is rather nebulous, and perhaps "Zu erreichen" would have been more meaningful, which would require a different word than לאחז in MT.51

Duhm also suggests that in the "alien unit"

… die bösen Parasiten herunterfallen v. 13b; während diese vom Frührot rot beleuchtet werden, stehen sie da wie Schande (לְבוֹשׁ) v. 14b; dann aber verschwinden sie, sagt v.15, wieder schleunig im Dunkeln und müssen von ihren bösen Werken abstehen.52

Driver and Gray note "But 15 upon this interpretation does not follow 14b well."53 The tentative wie Schande (כְּמוֹ לְבוֹשׁ) does not fit the context. Moreover, Duhm's criterion for sub-dividing the wicked into two groups meriting different punishment is rather strange. Indeed, his interpretation raises more questions than any of the commentaries that have been considered above.

Driver and Gray consider Beer's emendation of MT ויתיצבו into וְתִצְבַע or וְתִצְטַבַּע (cf. BHK and BHS) as being "clever," and adopt it.54 One should, however, note that the verb צבע does not occur in the Tanakh, though one finds it in cognate languages: Akkadian ṣibûtum, ṣubâtu "dyed stuff"; Arabic صَبَخَ "dye"; and, Aramaic צְבַע "dye."55 The adjective צָבוּעַ "variegated" occurs only once (Jer 12:9), and the noun צֶבָע "dye, dyed stuff" occurs trice (but only in Jud 5:30). Obviously, ויתיצבו and וְתִצְבַע or וְתִצְטַבַּע are orthographically rather different, and one cannot assume that a scribal error occurred, which resulted in an original וְתִצְטַבַּע becoming ויתיצבו. Postulating that the original was וְתִצְבַע or וְתִצְטַבַּע appears utterly arbitrary.

Ehrlich does not provide for our strophe a coherent interpretation but rather observations on some of its verses. He finds that the ketib ידעתה שחר is better than the Qere, since in the poetical books שחר never occurs with the article; Hos 10:5 (בַּשחר) and Isa 58:8 (כַּשחר) are probably incorrect vocalizations.56 Notably, he has nothing to say about v. 13. In v. 14 he insightfully points to a feature of the seal that has been missed by commentators-its script. He says:

Das Bild in V. 14a versteht man am sichersten von der Ordnung der Schrift. Die auf dem Siegel verkehrt laufende Inschrift ist dem Dichter ein Bild der Unordnung, die sich in der regelrechtenSchrift des Abdrucks gleichsam in Ordnung verwandelt. Ebenso wandelt sich die Erde beim Lichte; was im Dunkel der Nacht wie Chaos war, zeigt sich am Morgen als Ordnung.57

Ehrlich's treatment of our strophe succinctly conveys the exegetical difficulties and the inadequacies of some of the solutions that have been proposed. He concludes:

Dieser Gedanke Schliesst sich freilich an das Vorhergehende nicht recht an, scheint mir aber immer noch besser zu passen als das, was andere mit oder ohne Hilfe von Emendation hier herauslesen.58

Dhorme notes that in v. 12

The morning like the down, is personified. Both receive orders and docilely follow the instructions given them. The dawn has eyelids (3:9; 41:10). It is capable of knowing the position allocated to it, but it is God alone who can instruct it.59

In his view

By far the commonest explanation is that which regards the 1st hemistich as depicting the awakening of nature in the first rays of dawn, the objects then assuming their distinct contours, like clay under the seal.60

This perspective does not agree with Dhorme's lengthy discussion of כחמר חותם, in which he reaches the conclusion that

… we may identify the "clay of seal" or the "sealed clay" of our verse with the ṭin maḫtûm of the Arabs, the σφραγις of the Greeks, the lemnia of Pliny. One of its characteristics was its red color which made it resemble minium. The pink hues of the earth at sunrise justify the comparison: the earth becomes lie sealed clay!61

It is not clear from this explanation whether the seal metaphor deals with sharpness of relief or a hue of colour? In v. 14b Dhorme adopts the reading וְתִצָּבַע instead of MT ויתיצבו, saying "The plural 'they stand forth' can only with difficulty stand beside 'like a garment.'"

Tur-Sinai does not disappoint the reader with his original insights into our strophe. In his view, שַׁחַר is etymologically derived from שָׁחֹר "black" and means "the blackness." Thus, v. 12 speaks about separation of light, בֹּקֶר, from blackness, שַׁחַר.62 He finds both the Ketib ידעתה שחר and the Qere ידעת השחר unacceptable and opt for the more natural הודעת, which he inaptly renders by "caused to know." Regarding v. 13 Tur-Sinai says:

However strange the idea may seem to us, this is - according to the order of the verses - the purpose of the command to the blackness and the morning: that they should take hold of the ends of the earth - i.e. put up their stand each at a different end of it - in such manner that there will be light for the just and darkness for the wicked, so that the later "may be shaken out of it … and their (the just persons') may be withheld from the wicked" (v. 15). The wicked are thus to be thrown into the frightful darkness of the sea.63

Tur-Sinai is honest in considering his description as being strange - which it is. But being honest is not being helpful in this case. Moreover, his understanding of v. 14 is even stranger. He says that:

… here, too, it is the black clouds that threaten the wicked and behind which the waters of the celestial sea are hidden, and it is the waters, therefore, that 'stand as (in) a garment' (ויתיצבו כמו לבוש) lest they fall upon the just.64

Gordis observes: "Not only is this interpretation far-fetched, but it creates a hapax legomenon."65 Clines regards Tur-Sinai's interpretation "an extraordinarily implausible suggestion."66

In Gordis' view, in v. 13 "a more vivid figure emerges if it is rendered: 'so that You might take hold of the ends of the earth,' going back to the pronoun in צִוִּיתָ (Ibn Ezra)." He understands v. 14 a as being a metaphor for the earth, which "at night has neither shape nor color, both of which become evident with daylight," admitting that, "It is, however, undeniable that this interpretation requires a great deal of supplementary 'background' to be at all intelligible."67 Clines summarizes Gordis' explanation of v. 14 by saying,

Gordis has an elaborate interpretation, which, however, fails to carry conviction: he reads תתהפך כַּחֹמֶר חַיָּתָם ויתיצבו כֻּלָם יֵבשׁוּ "their soul, i.e., they, is turned round and round in the mire, they all stand (i.e., are arraigned, in judgment), they are put to shame." The emendation of חותם "seal" to חַיָּתָם "their life" is plausible enough, but the other usages of הפך hithpael do not support "turn round and round" (it means rather "turn this way and that"). כחמר "like clay" is revocalized to כַּחֹמֶר, a contraction of כְבַחֹמֶר "as in the mire." The second is much less persuasive a reconstruction since it represents a declination from the elevated poetry of the chapter, and there is no apparent connection with the theme of the coming of the morning.68

Kissane adopts the emendation of MT ויתיצבו into וְתִצְבַע or וְתִצְטַבַּע that has been suggested by Beer and Ehrlich (BHK).69 The only novel notion in Hakham's interpretation is taking ויתיצבו as referring to images and scenes that would appear (מראות ומחזות יתיצבו נגד עיני הצופה) as the light grows. This abstract sense appears to be too modern for יתיצבו of the Tanakh.70 Habel, like many commentators, personifies morning and dawn, but unlike other exegetes he makes Dawn female ("her place") though MT has מְקֹמוֹ. He takes ידעתה = "assigned," which is unattested in the Tanakh; assumes that the referent of לאחז is Job; takes v. 14a to mean "It changes like clay under a seal," assuming that the change is in relief and colour, which is unrealistic; and, takes in v. 14b the undefined "they" as the referent of ויתיצבו.71 Pope's translation of our strophe introduces several new meanings for standard words in the Tanakh, but maintains the generally accepted figure. For instance, he takes ידעתה = "posted"; לאחז = "snatch off"; כנפי = "skirts"; תתהפך = "it changes"; יתיצבו = "tinted"; ימנע = "are robbed"; and, רמה = "upraised." These translations amount to using a convenient but unaccepted vocabulary.72 Good notes that "יצב often means to take a military station, and the image seems to be of the earth taking station at dawn. The implied uniform may be the dawn's light."73 While Good's military notions shed new light on the figure conveyed by our strophe, this figure remains almost completely undeveloped.

Even this rather brief sample of exegetical efforts directed at deciphering the meaning of vv. 12-15, shows the considerable challenges that commentators faced. The interpretations that have been reviewed demonstrate clearly that most exegetes adhere to a perception which is inherently incoherent.74 There is little agreement about the referents of the verbs in the strophe. The assumed metaphors seem to be too complicated for their intended role.75 Acceptance of the reading רשעים exacerbates the tension between the pastoral spreading of the morning light and the aggressive treatment of the wicked. Over this set of particulars hovers the fundamental issue: "Why would God's question in v. 12 be of any interest to Job?" Obviously, without there being any personal interest in the natural phenomenon the challenge in God's question would be reduced to an idle rumination and lose the force for affecting Job's positions. Commentators have not yet adequately addressed this issue.

It seems that at the present time exegesis is not yet comfortable with the figure that our strophe presents. It is not an accident that a very recent commentator such as Clines, professing a sense of desperation, adopted G. R. Driver's cosmological interpretation. In the following section a solution to the difficulties in vv. 12-15 will be proposed that capitalizes on the possibility that the figure addressed in these verses is that of an at dawn wake-up of a military encampment preparing for an imminent battle.

C PROPOSED SOLUTION

God asks Job in v. 12 whether he knows at what time each day would appear, and at what place on the eastern horizon would the first rays of light show up. This question, which dominates our strophe, does not appear to be of the same caliber as the questions "Where were you when I founded the earth?" (v. 4) and "Who shut the sea within doors?" (v. 8). While the first two questions refer to majestic events in scope and in utility, the question in v. 12 is rather confined in time and place. Moreover, the knowledge displayed in v. 12 might seem to have been generally of little interest in an agricultural society and unavailable, because standardized time measuring devices were not in use.76 Whether the first rays of light breakout at point X would seem to have been for the ancients a datum of little consequence (Ps 19:6). Why did the author include this question among the first in God speeches? Modern exegesis seems to be oblivious of this issue.

1 Pre-battle tactical manoeuvers

While civilians in ancient societies might have paid little attention to when and where dawn occurs this information was of paramount importance to commanders who often waged battles in open terrain and uninhabited areas. When two armies moved to battle each other in open terrain they were careful of not committing unilaterally one's forces to position, and phalanx orientation. It was not unusual that one side sent messengers to the opponent, challenging him to do battle at a particular site and time. Indeed, in the ANE the war "protocol" for battles in open terrain required some negotiation and agreement on the site of the battle, its time, and coordination of the moves by the opposing forces that were arrayed for battle. Liverani observes:

the battle had to take place in an area known to both sides, an open space suitable to the movement of the armies and to the requirement that each should enjoy a clear view of the other; this also means that it must take place during the day. … The battle itself does not take place "suddenly" or by surprise, but when both armies are properly arrayed.77

Those who did not follow this protocol were contemptable warriors who were treated harshly when defeated.78

Obviously, there were kings who knew the rules but chose not to follow them. In this case, the two opposing forces in open terrain usually gravitated to a battle site that had some advantages to both sides, or the battleground was forced upon them by topography. The side that was in possession of information on the time and place of dawn had a considerable tactical advantage over the side that did not have this information. It could agree with the enemy, or force the enemy, to start the battle at a time when he is not fully prepared and at phalanx orientation that maximizes blinding of the enemy by the sun.

The author knew that God's knowledge of the time and place of dawn would be meaningful to Job and would impress him. Job who is described as being a very rich person had to maintain a security force for protection against robbers and raiding parties (Gen 14:14, Job 1:15-19), and lead it to battle. The Tanakh might be referring to these elements as נערים "the youngsters." (Job 1:15-19). Also, in ancient times, there was no national army. In the case of an emergency, the entire available force of citizens would be called up for service. For instance, peasants were always liable for military service all through the history of Assyria.79 Wiseman writes: "With the exception of bodyguard, with its contingent of foreigners, the Assyrian kings relied principally on the mass call-up or levy of native Assyrians."80 These contingents of essentially farm-hands, mobilized in time of need, were commanded in the battle by their own governors/princes, because of familiarity, ease of communication, and loyalty considerations.81 The author's characterization of Job in the book would suggest to any reader that he was well aware of the tactical advantages that knowledge of the time and place of dawn would provide. Moreover, Pinker has shown that the author of the Book of Job was apparently knowledgeable about military matters and often drew upon these sources.82

2 Military tenor of vv. 12-15

The significance for military tactics of God's third question to Job seems to have shaped the text of our strophe and its tenor. Each verse in the strophe contains one or more military terms, or terms that could have reasonably been military terms. This concentration of military terminology marks the strophe as being essentially a text that describes a military activity.

In v. 12a צוית "charge, command, order," connotes characteristics of military communication (Jos 6:10, 2 Sam 13:28-29, 18:12, 1 Kgs 22:31, Ps 33:9, 148:5; Lam 3:37). It is also possible that ידעתה מקמו in v. 12b is a military terminus technicus for placing a unit in a phalanx. Since early antiquity, major battles in open terrain between nations involved clashes of masses of people against masses of people. For instance, an Old Babylonian text from Mari on the Euphrates, which was written in the early 2nd millennium BCE, lists an army of 100,000 men with 20,000 archers and 1,500 cavalry.83 It seems that even at those times a rudimentary phalanx organization existed that eventually developed into a more sophisticated and regimented form of warfare. Each local contingent, commanded by its prince, occupied a section of the phalanx and had to maintain cohesion during the battle. It was obviously a feat to organize such masses of infantry, specialized fighters, and mobile units and keep the various units intact for manoeuvering as fighting entities.84 Perhaps, to enhance the military tenor of the strophe the author is borrowing in v. 12b this military term (of placing a unit within a larger battle formation), and is using it for describing the placement of the sun.

In v. 13b the word ינערו might be a clever play on יעירו נערים, "young soldiers would wake up," connoting in ינערו a fusion of נער and יער. It is also possible that the term was routinely used in the military for a quick wake-up of an encampment. How such military wake-up was conducted is alluded to in v. 14a, but it would be familiar even to a current reader who served in the military. The soldiers executing the wake-up went from mat to mat, on which soldiers were sleeping, grabbed (אחז) at the extremities (בכנפות) of the mat that were on the ground (הארץ) rolled the sleeping off the mat and threw the overturned mat on them. This kind of quick, effective, but relatively quiet wake-up, is not surprisingly described by the metaphor תתהפך כ[ב]חמר חותם; i.e., "turned around as in the clay of a seal," where both the order of words and each letter are reversed. In the case of a sleeping soldier, his mat and he are overturned in the wake-up, just as the writing on a seal. The effects of such wake-up are described in v. 14b by means of the term יתיצבו, which has well known military associations (Deut 7:24; 9:2; 11:25; Josh 1:5; 2 Sam 21:5; Isa 21:8; Jer 5:26; 46:4, 14; Hab 2:1; Job 33:5; 41:2; Lam 2:4; 2 Chr 11:13; 20:6, 17). The soldiers quickly responded to the wake-up by standing ready to receive their orders.

The metaphor כמו לבוש in v. 14b, which has tried exegetical ingenuity for generations, is apparently also a military term. It should, perhaps, be read כְּמָגֵן לָבוּשׁ "worn armour," reflecting an incorrect completion of the abbreviation כמ. The worn armour was intended to protect a combatant's torso and consisted of two metal plates (front and back) shaped as the body contours and tied to each other, or one piece tied in back (as a corset). This armour was taken off during sleep and stood next to the sleeping mat to preserve its shape. The metaphor יתיצבו כמגן לבוש "they (soldiers) stand as worn armour" would have been obvious to the ancient reader. It would convey clearly immediate readiness.

The phrase ימנע אורם in v. 15a is also a military terminus technicus, which refers to the blinding of the soldiers in a phalanx by the changing position of the sun. Even battles that started with no side having any "sun advantage" could have been dragged out to lend some side this advantage. Thus, מנע אור was an important factor in any pre-battle deliberation. Finally, in v. 15b the military term זרוע רֹמָה "the throwing hand" is used, which is probably equivalent to יד ימין "right hand, strong hand." It refers to the arm of the military with the longer reach, like archers, javelin throwers, and sling shooters.

3 Interpretation of vv. 12-15

The figure associated with vv. 12-15 is one in which the commanders of a military force, encamped for night rest, are in possession of a vital intelligence datum-time and place of dawn. They intend to force the positioning of forces so that they would have a "sun advantage." A quiet and quick wake-up is necessary. This figure is in the background of God's question to Job in v. 12. God by being able to order the time and set the place of dawn can always blind his enemies and smite them. Man cannot do so.

In v. 12 "Dawn" (השחר) is personalized, and God commands the hosts of heaven. As a unit in a phalanx Dawn has a place assigned to it by God. He asks Job: Have you ever ordered (the time of) morning, made known (to) the dawn its place?

If Job, as a commander of a military force, had the capability to know the time and place of dawn, he could make a move to blind his enemies. He could as surreptitiously as possible wake up his force (ינער) and force the enemy's hand in phalanx orientation.85 This perception rules out the reading רש ע ים in v. 13b. However, the reading רָאשִׁים, as suggested by Merx for the questionable רש ע ים, would fit the military wake-up.86 Moreover, there are many cases in the Tanakh where a א is missing inside a word. In particular, the רש/ראש confusion is relatively well attested to in the Tanakh. See for instance 2 Sam 12:3-4 ראש and רש; Prov 10:4 ראש for רש; Prov 13:23 ראשים for רשים; Isa 41:20 ברוש but בראוש in 1QIsaa; and, Job 8:8 רישון for ראשון. The reading ראשים is certainly possible. Moreover, the suggested context for our strophe makes it probable, since only the head of a sleeping soldier would be seen when his sleeping mat is overturned.

The word ממנה in v. 13b should be read מִמְּנֹחַ "from the rest" (1 Chr 6:16). The confusion has been probably caused by the orthographic similarity of the letters ה and ח in the early square script, where the ה is written as the ח but with the top less extended to the left. This confusion of letters is attested in the Ketib-Qere apparatus and occurs also outside it.87 Thus v. 13 reads: to grasp at the extremities on the ground and heads are shaken off rest.

The two metaphors in v. 14 have tantalized most exegetes. To the best of my knowledge only Ehrlich notes the reversed writing on a seal but not the reversal of each letter. It is easy to imagine that the chatter among soldiers contained such bits of information as "When they wake you up, you will turn around as the writing in the clay of a seal." This understanding requires the reading כְּבַחֹמֶר instead of MT כחמר.88 The Ketib-Qere apparatus indicates that a ב is rarely missed in the Tanakh. Still, that is the case in 2 Kgs 22:5 and Jer 52:11 בבית (K) but בית (Q). Perhaps in v. 14 such omission was caused by haplography, because of the two preceding כ. The shift in number from ינערו (plural) to תתהפך (singular) and again to יתיצבו (plural) can be easily understood in the suggested context. The wake up is of the many, each of them would be turned in a "military" manner, and the many woken up would stand to order. One might have expected יתהפך instead of MT תתהפך, but such confusion of person is not unusual and is attested to elsewhere.89

We have suggested that כמו in v. 14b is a later incorrect completion of the abbreviation כמ, which stands for an original כְּמָגֵן. Such confusions have been identified in many cases in the Tanakh.90 Buttery observes that in the 7th century (BCE) Assyrian infantry,

The shock troops, comprised of units of various types, were mainly spearmen who led the attack in hand fighting and the assault on fortified cities. These heavy infantry were protected by long mail coats and a pointed helmet with a metal hood attached.91

Perhaps Jeremiah (46:3-4) refers to such troops and to the personal armour (לבשו הסריונות) that they wore (cf. Ezek 23:24). It is notable that Jer 46:4 contains the words התיצבו and לבשו in a manifestly military context.92 Jeremiah may be also alluding to helmets (והתיצבו בכובעים).93 Hanging of the helmet and armour, when resting, is probably alluded to in Ezek 27:10 (מגן וכובע תלו־בך). These observations suggest that the metaphor in v. 14b might be drawing on a practice of hanging the personal worn-armour and helmet on a spear (in some fashion) next to the mat on which a warrior slept. Such practice would have also protected the sleeping from being trampled at night by night traffic. Our insights into likely soldierly behaviour lead the following interpretation of v. 14: you will turn around as the writing of a seal, and (immediately) they stand to order as the worn armour.

The strophe closes aptly with a description of the dramatic consequences that the knowledge of the time and place of the dawn might have on a battle. The enemy (רשעים) would be deprived (ימנע) of their light (אורם), because they would be blinded by the light of the rising sun. This would enable an easy defeat of the enemy; i.e., metaphorically זרוע רֹמָה תשבר "the throwing hand would be broken."

As important as "sun advantage" is, its main utility is seeing the battlefield. It is notable that the knowledgeable author is aware that "close quarters" or "man-to-man" combat would not be affected by the blinding sun, but rather the capability of the long-range throwers. Buttery notes that the main power in the Assyrian army of the 7th century (BCE)

… rested with the archers who were used in every type of attack and used powerful composite bows. The early archers, in long mail coats, were accompanied by a shield bearer who carried a small round shield to protect the archer's face.94

With his face covered by such small shield, to protect the archer from the blinding sun, the most important arm in an army, with the longest reach on the battlefield, was immobilized. From this perspective, v. 14 reads: The wicked (enemy) would be deprived of their light (seeing), and the throwing arm would be broken.

Our strophe with some minor emendations reads:

Our strophe can be paraphrased:

12Have you ever ordered the time when morning would begin, and made known to dawn its place. 13So that the lads could grasp at the extremities on the ground and shake heads off their resting place. 14Turning you as the writing in the clay of a seal, all standing up to order as the worn armour. 15The enemy would be blinded by the sun, and its long-range arm would be destroyed.

This interpretation is perhaps alluded to in vv. 23-24.

D CONCLUSION

Terrien, in his assessment of God's speeches, has more questions than God, all addressed to God. He asks:

Why should he [Job] be forced to hear lessons in geology, astronomy, meteorology and zoology, while he is consumed by disease and unrequited love? God's inexhaustible energy is matched only by his eloquence. In turn, he pictures the settling of the earth upon its base, the shutting up of the sea within its bounds, the waking of "Dawn"-a little goldchild, crimson as the clay of Lemnos which men use with their seals-shakes the wicked like parasites out of earth's night robe.95

This exegetical attitude, as was shown in the Analysis section, does not lead to cogent interpretations of our strophe.

The suggested approach in this study is that God asks Job a relevant and practical question. It refers to military experience that a man of Job's stature had and many of the book's readers shared. Consequently, the author can by means of some military terminology evoke scenes that would be rich in meaning for Job and the readers. The minor emendations that have been suggested help to bring out the military aspect of the strophe. Within this military framework, knowledge of the time of daybreak and the place of dawn is of great importance. Such intelligence enables advantageous positioning of forces. The two basic elements in our strophe are "knowledge" and "advantageous utilization." God is effective because he can combine these two elements. Man can never be as effective as God, because his "knowledge" will always be inadequate. While this example has been somewhat tarnished by creation of accurate clocks and better understanding of astronomy, the basic message continues to be valid.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Andersen, Francis I. Job: An Introduction and Commentary. London: Inter-Varsity Press, 1976. [ Links ]

Arnheim, Heymann. Das Buch Job. Glogau: H. Prausnitz, 1836. [ Links ]

Barton, George A. Commentary on the Book of Job. New York: Macmillan, 1911. [ Links ]

Beer, Georg. Der Text des Buches Hiob. Marburg: N.G. Elwert, 1897. [ Links ]

Brenton, Lancelot C. L. The Septuagint with Apocrypha: Greek and English. 1st ed. Peabody: Hendrickson, 1987. [ Links ]

Clines, David J.A. Job 38-42 (WBC 18B; Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2011). [ Links ]

Budde, Karl. Das Buch Hiob übersetzt und erklärt. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1896. [ Links ]

Buttery, Alan. Armies and Enemies of Ancient Egypt and Assyria. Goring by Sea: War Game Research Group, 1974. [ Links ]

Caspari, C. P. Das Buch Hiob (1, 1-38,16) in Hieronymus's Uebersetzung aus der alexandrischen Version nach einer St. Gallener Handschrift. Christiania: Brøggers Bogtrykkeri, 1893. [ Links ]

Clines, David J. A. Job 38-42. WBC 18B. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2011. [ Links ]

Cornelius, Izak. "The Sun Epiphany in Job 38:12-15 and the Iconography of the Gods in the Ancient Near East-the Palestinian Connection." JNSL 16 (1990): 25-43. [ Links ]

Cox, Samuel. A Commentary on the Book of Job. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1894. [ Links ]

Delitzsch, Franz. Biblical Commentary on the Book of Job, Volume II. Edinburgh: T & T Clark's, 1869. [ Links ]

Del Medico, Henry E. "La traduction d'un texte démarqué dans le Manuel de Discipline (DSD X, 1-9)." VT 6/1 (1956): 34-39. [ Links ]

Dillmann, August. Hiob. Leipzig: Hirzel, 1891. [ Links ]

Dhorme, Eduard. A Commentary of the Book of Job. London: Nelson, 1967. [ Links ]

Driver, G. R. "Two Astronomical Passages in the Old Testament." JTS 4 (1953): 208-12. https://doi.org/10.1093/jts/IV.2.208 [ Links ]

_______. "Abbreviations in the Massoretic Text." Text 1 (1960): 112-31. [ Links ]

_______. "Once Again Abbreviations." Text 2 (1962): 76-94. [ Links ]

Driver, Samuel R. and George B. Gray. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Job. Volumes I and II. ICC. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1921. [ Links ]

Duhm, D. Bernhard. Das Buch Hiob. KHC. Leipzig: J.C.B. Mohr, 1897. [ Links ]

Ehrlich, Arnold B. Psalmen, Sprüche, Hiob. Vol. 6 of Randglossen zur Hebräischen Bibel, Textkritisches, Sprachliches und Sachliches. Hildsheim: Georg Olm, 1968. [ Links ]

Ewald, Georg H. A. Commentary on the Book of Job. London: Williams and Norgate, 1882. [ Links ]

Fishbane, Michael. "Abbreviations, Hebrew Texts." IDB Suppl:3-4. [ Links ]

Fohrer, Georg. Das Buch Hiob. KAT 16. Gütersloh: Gerd Mohn, 1963. [ Links ]

Gaab, Johann F. Das Buch Hiob. Tübingen: J. G. Cotta'schen, 1809. [ Links ]

Good, Edwin M. In Turns of Tempest: A Reading of Job with a Translation. Stanford: Stanford University, 1990. [ Links ]

Gordis, Robert. The Book of Job: Commentary, New Translation, and Special Notes. New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1978. [ Links ]

Gray, John. "The Massoretic Text of the Book of Job, the Targum and the Septuagint Version in the Light of the Qumran Targum (11QtargJob)." ZAW 86/3 (1974): 331-50. https://doi.org/10.1515/zatw.1974.86.3.331 [ Links ]

Habel, Norman C. The Book of Job: A Commentary. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1985. [ Links ]

Hakham, Amos. איוב ספר. Jerusalem: Mosad HaRav Kook, 1981. [ Links ]

Hengstenberg, Ernst Wm. Das Buch Hiob erläutert. Berlin: Gustav Schlawis, 1870. [ Links ]

Hufnagel, Wilhelm F. Hiob. Erlangen: Palmisch, 1781. [ Links ]

Keegan, John. A History of Warfare. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993. [ Links ]

Keel, Othmar. Jahwes Entgegnung Ijob: Eine Deutung von Ijob 38-41 vor Hintergrund der zeitgenössische Bildkunst. FRLANT 121. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1978. [ Links ]

Kennedy, James and Nahum Levison. An Aid to the Textual Amendment of the Old Testament. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1928. [ Links ]

Kissane, Edward J. The Book of Job. Dublin: Browne & Nolan, 1939. [ Links ]

Lamsa, George. Holy Bible from the Ancient Eastern Text: George M. Lamsa's Translations from the Aramaic of the Peshitta. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1933. [ Links ]

Liverani, Mario. International Relations in the Ancient Near East, 1600-1100 BC. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001. [ Links ]

Mangan, Céline. "The Targum of Job." Pages 1-98 in The Targums Job, Proverbs, and Qohelet. Vol. 15 of The Aramaic Bible. Translated by Céline Mangan, John Healey, and Peter S. Knobel. Collegevile: Liturgical Press, 1991. [ Links ]

Merx, Adalbert. Das Gedicht von Hiob. Jena: Mauke's Verlag, 1871. [ Links ]

Perdue, Leo G. "Creation in the Dialogues between Job and His Opponents." Pages 197-216 in Das Buch Hiob und seine Interpretationen: Beiträge zum Hiob-Symposium auf dem Monte Verità vom 14.-19. August 2005. Edited by Thomas Krüger, Manfred Oeming, Konrad Schmid, and Christoph Uehlinger. Zürich: Theologischer Verlag Zürich, 2007. [ Links ]

Perles, Felix. Analekten zur Textkritik des Alten Testaments. New Series. Volumes I and II.Leipzig: G. Engel, 1922. [ Links ]

Pinker, Aron. "Two Military Metaphors in Elihu's Fourth Speech (Job 36:19-20)." JSem 26/1 (2017): 1-32. https://doi.org/10.25159/1013-8471/3104 [ Links ]

_______. "On the Meaning of Job 34:20 in Elihu's Second Speech." BN 174 (2017): 3-20. [ Links ]

_______. "An Examination of Breaking (ואשבר) in Job 38:10." RB (forthcoming). [ Links ]

Pope, Marvin H. Job. AB 15. Doubleday: Garden City, 1986. [ Links ]

Reichert, Victor E. Job. London: Soncino Press, 1960. [ Links ]

Rignell, L. Gösta. The Peshitta to the Book of Job: Critically Investigated with Introduction, Translation, Commentary and Summary. Edited by Karl-Erik Rignell. Kristianstad: Monitor, 1994. [ Links ]

Stec, David M. The Text of the Targum of Job: An Introduction and Critical Edition. Leiden: Brill, 1994. [ Links ]

Terrien, Samuel. Job: Poet of Existence. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1957. [ Links ]

Torczyner [Tur-Sinai], Naphtali H. משלי שלמה. Tel Aviv: Yavneh, 1947. [ Links ]

Tur-Sinai, Naphtali H. The Book of Job. Jerusalem: Kiryath Sepher, 1967. [ Links ]

Wiseman, D. J. "The Assyrians." Pages 36-53 in Warfare in the Ancient World. Edited by John Hacket. New York: Facts on File, 1984. [ Links ]

Whybray, Norman. Job. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998. [ Links ]

Submitted: 30/10/2017

Peer-reviewed: 19/01/2018

Accepted: 01/03/2018

Aron Pinker, 11519 Monticello Ave., Silver Spring, MD 20902, USA.

1 Aron Pinker, "An Examination of Breaking (ואשבר) in Job 38:10," RB (forthcoming).

2 Victor E. Reichert, Job (London: Soncino Press, 1960), 198. Reichert provides the following literal translation: "Has thou commanded the morning since thy days began, and caused the dayspring to know its place; that it might take hold of the ends of the earth, and the wicked be shaken out of it? It is changed as clay under the seal; and they stay as a garment. But from the wicked their light is withholden, and the high arm is broken."

3 David J. A. Clines, Job 38-42, WBC 18B (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2011), 1103.

4 Clines, Job 38-42, 1057.

5 Norman Whybray, Job (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998), 159-60.

6 Francis I. Andersen, Job: An Introduction and Commentary (London: Inter-Varsity Press, 1976), 276.

7 Clines, Job 38-42, 1103. Clines says: "The only moral language in the speeches is in 40:12; משפט, רשע, and צדק at 40:8 are used in a forensic, not an ethical, sense."

8 Clines, Job 38-42, 1103.

9 Lancelot C. L. Brenton, The Septuagint with Apocrypha: Greek and English, 1st ed. (Peabody: Hendrickson, 1987), 694.

10 The two versions reflect the editio princeps of the Targum of Job and can be found in the first Rabbinic Bible edited by Felix Pratensis and printed by Daniel Bomberg in Venice (1517). Cf. David M. Stec, The Text of the Targum of Job: An Introduction and Critical Edition (Leiden: Brill, 1994), 269*-71*. Gray rightly notes that: "By their very nature as the development of oral rendering and exposition of Scripture targums they are an indirect witness to the original Hebrew text, and with a fair amount of paraphrasing they are generally fuller than the MT." John Gray, "The Masoretic Text of the Book of Job, the Targum and the Septuagint Version in the Light of the Qumran Targum (11QtargJob)," ZAW 86/3 (1974): 335.

11 The rendition of the Targum into English is based on Mangan's translation. Cf. Céline Mangan, "The Targum of Job," in The Targums Job, Proverbs, and Qohelet, vol. 15 of The Aramaic Bible, trans. Céline Mangan, John Healey, and Peter S. Knobel (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1991), 82-83.

12 George Lamsa, Holy Bible from the Ancient Eastern Text: George M. Lamsa's Translations from the Aramaic of the Peshitta (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1933), 585. Rignell has: "12Since your days began have you commanded the dawn? You know where the place is of the morning. 13that it might take hold of the ends of the earth and the wicked might be thrown out of it, 14Their body shall be changed (and become) like clay and they shall stand as a garment. 15From the sinners their light is withheld, and the high arm is broken." Cf. L. Gösta Rignell, The Peshitta to the Book of Job: Critically Investigated with Introduction, Translation, Commentary and Summary, ed. Karl-Erik Rignell, (Kristianstad: Monitor, 1994), 318. In Ringell's opinion: "the Syriac 'translators' have, in their work, been too independent of the Hebraic text. Their translation is therefore of very little importance for the understanding of the Massoretic text. Above all this applies to the interpretation of the frequently occurring 'cruces interpretum'" See Rignell, Peshitta to the Book of Job, 4).

13 C.P. Caspari, Das Buch Hiob (1,1-38,16) in Hieronymus's Uebersetzung aus der alexandrischen Version nach einer St. Gallener Handschrift (Christiania: Brøggers Bogtrykkeri, 1893), 108. Hieronymus translates: "12aut numquid decum lucem constitui matutinam, aut cognoui Lucifer ordinem suam? 13adprehendere pinnas terrae, excutere impios ex ea. 14et tu sumens terre lutum figurasti animal et famosūm eum posuisti super terram? 15et abstulisti ab impiis lucem, aut brachium superborum comminuisti?"

14 Thus, deletion of 13b cannot be justified on the ground that at creation there were no wicked.

15 Georg Fohrer, Das Buch Hiob, KAT 16 (Gütersloh: Gerd Mohn, 1963), 503-4. Cf. also Henry E. Del Medico, "La traduction d'un texte démarqué dans le Manuel de Discipline (DSD X, 1-9)," VT 6/1 (1956): 34-39.

16 Leo G. Perdue, "Creation in the Dialogues between Job and his Opponents," in Das Buch Hiob und seine Interpretationen: Beiträge zum Hiob-Symposium auf dem Monte Verità vom 14.-19. August 2005, ed. Thomas Krüger et al. (Zürich: Theologischer Verlag Zürich, 2007), 205. In his view: "in the cultural world of Job in Babylon, it is the Akkadian deity, Shamash, who discovers through its penetrating rays the deeds of humans, including those who are wicked and subversive of divine and legitimate human rule."

17 Izak Cornelius, "The Sun Epiphany in Job 38:12-15 and the Iconography of the Gods in the Ancient Near East-the Palestinian Connection," JNSL 16 (1990): 25. Cf. also Othmar Keel, Jahwes Entgegnung Ijob: Eine Deutung von Ijob 38-41 vor Hintergrund der zeitgenössische Bildkunst, FRLANT 121 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1978).

18 Cornelius, "Sun Epiphany," 32.

19 Clines, Job 38-42, 1103. Clines says: "The only moral language in the speeches is in 40:12; משפט, רשע, and צדק at 40:8 are used in a forensic, not an ethical, sense."

20 G. R. Driver, "Two Astronomical Passages in the Old Testament," JTS 4 (1953): 210.

21 Canis Major and Canis Minor are two constellations, which for mnemonic purposes are customarily associated with the great hunter, Orion (constellation), as his hunting dogs, following him obediently across the sky. Sirius, also known colloquially as the "Dog Star," is the most prominent in its constellation, Canis Major. The heliacal rising of Sirius marked the flooding of the Nile in Ancient Egypt and the "dog days" of summer for the ancient Greeks.

22 LXX has in Ezek 16: רעותך for MT עורתך.

23 Driver, "Astronomical," 210.

24 Clines, Job 38-42, 1104-5. Clines (Job 38-42, 1049) renders our strophe: "12Since your day began, have you called up the morning, and assigned the dawn its place, 13so as to seize the earth by its fringes so that the Dog-stars are shaken loose? 14It is transformed like clay under a seal and all becomes tinted like a garment, 15as the light of the Dog-Stars fades, and the Navigator's line breaks up."

25 The ancient Arabs extended Leo farther than modern astronomers. They considered Castor and Pollux (Gemini) and Canis Minor to be "arms" or extensions of Leo.

26 Driver, "Astronomical," 211.

27 Robert Gordis, The Book of Job: Commentary, New Translation, and Special Notes (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1978), 447.

28 In the astronomical context a line of stars can become distorted or some of the stars invisible. In either case the term תשבר would not be adequate for describing the situation.

29 Heymann Arnheim, Das Buch Job (Glogau: H. Prausnitz, 1836), 220-21.

30 Arnheim, Job, 158. He says: "Weiter unten, 38,15, wird die Nacht geradezu das Licht der Freveler genannt."

31 Ernst Wm. Hengstenberg, Das Buch Hiob erläutert (Berlin: Gustav Schlawis, 1870), 323-24. He has: "12Hast du jemals den Morgen entboten, angewiesen dem Morgenroth seine Stelle? 13Daß es erfasse die Säume der Erde, und die Bösen von ihr ausgeschüttelt werden. 14Die Erde wandelt sich, wie Siegelthon, und jene stellen sich dar wie ein Gewand. 15Und genommen wird den Bösen ihr Licht, und der hohe Arm wird zerbrochen."

32 Perhaps Hengstenberg means "from horizon to horizon."

33 Hengstenberg, Hiob, 324. Hengstenberg thinks that the two-fold ע suspensum in the word רשעים (vv. 13 and 15) might reflect some spiritual meaning (cf. Ps 104:35).

34 August Dillmann, Hiob (Leipzig: Hirzel, 1891), 326. Actually, as Budde points out, "Morgen und Morgenröte (beide sind eins) in die Tätigkeit ein." Cf. Karl Budde, Das Buch Hiob übersetzt und erklärt (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1896), 229.

35 Dillmann, Hiob, 325. Dillmann notes that in the Qere ידעת השחר the article is not necessary. It possibly occurs because of the personal ending of ידעתָ.

36 Dillmann, Hiob, 325. Dillmann thinks that that suspended ע does not indicate a different reading (b. Sanh. 103b) but marks a rabbinic Midrash.

37 Dillmann, Hiob, 326.

38 Wilhelm F. Hufnagel, Hiob (Erlangen: Palmisch, 1781), 276-77.

39 Budde, Hiob, 229. Budde translates vv. 12-15: "12Hast du dein Lebtag dem Morgen entboten, Der Morgenröte ihren Platz gewiesen, 13Dass sie die Zipfel der Erde fast Und alle Bösen davon geschüttelt werden, 14Dass sie sich wandelt wie Siegelton Und in Falten legt wie ein Gewand, 15So dass den Bösen ihr Licht versagt wird, Und der erhobene Arm zerbricht?" Taking "Und in Falten legt" for ויתיצבו seems rather strange.

40 Budde, Hiob, 229. He says: "Eher wäre an יִתְיַצֵּב יְבוּלָּהּ (20:28) zu denken."

41 Franz Delitzsch, Biblical Commentary on the Book of Job (Edinburgh: T & T Clark's, 1869), 2:316.

42 Delitzsch, Book of Job, 2:317.

43 Delitzsch, Book of Job, 2:317. He says: "נָעֵר, combining in itself the significations to thrust and to shake, has the latter here, as in the Arabic naûra, a water-wheel, which fills its compartments below in the river, to empty them out above." This would aptly correspond to the turning over of a cot or sleeping mat.