Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.24 n.1 Pretoria 2020

https://doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/4965

Wodak, R. 2009. "What CDA Is About: A Summary of Its History, Important Concepts and Its Developments". In Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, edited by R. Wodak and M. Meyer, 1-13. London: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857028020.n1. [ Links ]

Xiong, X. M. 2007. "Reflection on the Present Adjustment of Primary and Secondary School Distribution in Rural Areas". Education and Economy 82 (2): 50-53. [ Links ]

Yang, L. 2010. "Reviews and Reflections upon the Policy of School Mapping Restructure". In Blue Book of Education: Annual Report on China's Education, edited by L. Yang, 73-85. Beijing: Social Science Academic Press. [ Links ]

YEB (Yulin Education Bureau). 2005. Suggestions on Promoting Yulin Rural Compulsory Education System. Yulin: Education Bureau Office. [ Links ]

YEB (Yulin Education Bureau). 2009. Annual Report of Basic Education Development in Yulin (2008). Yulin: Education Bureau Office. [ Links ]

YEB (Yulin Education Bureau). 2013. Self-Inspection of the Balanced Development of Compulsory Education in Middle and Primary Schools. Yulin: Education Bureau Office. [ Links ]

YEB (Yulin Education Bureau). 2015. Annual Report ofBasic Education Development in Yulin (2014). Yulin: Education Bureau Office. [ Links ]

Zhao, D., and B. Parolin. 2011. "School Mapping Restructure in China: What Role for the Small Rural School?" Frontiers of Education in China 6 (2): 248-78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11516-011-0131-5. [ Links ]

Zhou, Z. K., X. J. Sun, Y. Liu, and D. M. Zhou. 2005. "The Mental Development and Education of Rural Left-behind-Children". Journal of Beijing Normal School University 1: 71-79. [ Links ]

1 1 RMB = approximately 0.16 USD

2 Interviews and government policy texts were originally in Chinese and translated by the first author into English for the purpose of analysis. The translation has been checked by two professional translators.

ARTICLE

Fostering an equitable curriculum for all: a social cohesion lens

Mutendwahothe Walter Lumadi

University of South Africa Lumadmw@unisa.ac.za https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0121-7386

ABSTRACT

The discourse of equal education in the South African education system is polemical, and achieving its aim is a daunting task. The premise of this study affirms that fostering an equitable curriculum for all is essential for social cohesion. The achievement of greater equity through schooling is vital to society and national identity because the citizenry purports to believe in the universal right to pursue quality life for all. I contend that curriculum implementation should reject the dominant miseducation within society that enables and legitimises the inequitable treatment of its citizenry, at the expense of democracy. It is worth noting that all human beings are created equal and endowed with certain inalienable rights, among which are life and liberty. A qualitative approach was employed in the study. An equitable curriculum must strive to include the lives of all those in society, especially the marginalised and dominated. Undemocratic, persistent inequities exist in the education system, and in religious and political agencies that promote the opposite of a tolerant and humane society. Equity in a curriculum is pivotal to the alleviation of injustices in society and is a panacea to the perpetuation of unfair practices. Fostering an equitable curriculum for all is mostly based on the intertwined principles of social justice, mainly equity, access, participation, and rights.

Keywords: equity; curriculum; social justice; equality; participation; social cohesion; rights; access

Introduction

Inequality in the school curriculum is linked to the major problems in society. The means of mitigating these inequalities are of paramount importance. This is of great interest since learners require quality education, which is a cornerstone for a guaranteed future. Equality in the curriculum will, to a large extent, guarantee every human being a better position in society. In the apartheid era, whites held nearly all the political power in South Africa, with other "races" almost completely marginalised from the political arena. The end of apartheid allowed equal rights for all citizens regardless of perceived racial origins. South Africa still grapples to correct the social inequalities created by the apartheid regime. Despite a rising gross domestic product, indices for poverty, unemployment and income inequality show they are still more prevalent among blacks, coloureds and Indians (Carr 2001).

Educational inequity erodes the values of equality of opportunity and social mobility. Every learner has a right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, irrespective of parental status. An equitable curriculum that provides equal opportunities to learners with the relevant needs is a necessary component to address rampant income inequality, which hampers economic growth and threatens democracy. While equality means treating every learner the same, equity means making sure every learner has the support they need to be successful. Equity in education requires putting systems in place to ensure that every learner has an equal opportunity of achieving worthwhile results.

It is everyone's responsibility to create a lens for social cohesion. It requires political will, a shared consensus and participation in processes, even though this may be distinctly uncomfortable. Political will in some of the township and rural schools in South African provinces is currently demonstrated through leadership that prioritises the achievement of social cohesion, which changes unequal, system-wide relationships of power and is focused on improving the quality of education. Freire (1972) put forth that teachers should attempt to "live part of their dreams within their educational space". Classrooms can be places of hope where learners and teachers gain glimpses of the kind of society they could live in and where learners acquire the academic and critical skills needed to make it a reality. Coleman et al. (1966) too averred that learners need to be inspired by one another's vision of schooling, which would eventually enable them to balance equality, equity and social justice, as highlighted in Figure 1.

a) Social justice requires specific intervention to secure equality and equity

b) Equality: every human being has an absolute and equal right to common dignity and parity of esteem and entitlement to access the benefits of society on equal terms

c) Equity: everyone has the right to benefit from the outcomes of society based on fairness.

The implications of the model depicted in Figure 1 are explicit. Social justice is realised when the principle of equality is reflected in the concrete experience of all parties found in any given social situation. Furthermore, experience must be evaluated in the results on the extent of equity. When the two elements are interwoven, the level of social justice rises.

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

This study is underpinned by a theoretical framework of "education for all", which is a global commitment to provide quality basic education for all learners and adults. The concepts of "education for all" and "curriculum" are interweaved. "Education for all", on the one hand, emphasises the need to provide access to education for traditionally marginalised groups, including girls and women, indigenous populations and remote rural groups, street children, migrants and nomadic populations, people with disabilities, linguistic and cultural minorities. A comprehensive rights-based approach must be dynamic, accounting for different learning environments and different learners.

The Concept of Curriculum

The concept of "curriculum, on the other hand, is derived from the Latin word currere, which means to run or race. In time, it came to mean the course of study" (Lumadi 1995). It can also be viewed as the sum of experiences leading to the learning that occurs under the auspices of the formal institution, whether or not these are part of the written content guide. Moreover, it can be defined as an organised set of intended learning outcomes leading to the achievement of educational goals. It may also allude to the knowledge and skills imparted to learners; this includes the learning standards they are expected to meet, and the units and lessons offered by teachers. A curriculum is the primary vehicle by which economically and socially marginalised adults and children can lift themselves out of poverty and obtain the means to participate fully in their communities (Gorski 2013).

A curriculum should not be viewed as a static commodity to be considered in isolation from its greater context; it is an ongoing process and holds its own inherent value as a human right. Not only do people have the right to receive quality education, they also have the right to be equipped with the skills and knowledge that will ensure long-term recognition of and respect for all human rights. In this study, it should be regarded as a plan for teaching and learning that is conceptualised in the light of certain selected outcomes. It encompasses all the planned learning opportunities offered to learners by the educators in institutions and the experiences that the learners encounter when the curriculum is implemented.

Habibis and Walter (2009, 69) took a step further by mentioning that curriculums should aim to achieve universal education for all, specifically to "ensure that all learners, will be able to complete a full course of schooling". The socio-cultural theory (Vygotsky 1986) that relies on the zone of proximal development and the constructivist (Piaget 1964) theories of learning further informed the study. Some of the schools in South Africa dictate the choice of subjects to learners. It is presumed that these theories, though quite different, subsume the use of dialogue and conversations (facilitated by the classroom teacher) to promote an inclusive policy to all learners to deal with their challenges when learning all school subjects. There is a controversial belief that the gateway subjects, such as mathematics and physical science, are complex and as a result are meant for the chosen few. In some of the studied schools, only boys can pursue this demanding stream because they are perceived to be tough and strong. These subjects are crucial for individual freedom and economic development. They are used as a basic entry requirement into any of the prestigious courses such as medicine, engineering and accounting, among other degree programmes. Despite the pivotal role that these subjects play in society, it is alleged that there has always been woeful performance from girls in these subjects.

Piaget (1964) argued that the growth of learners' knowledge occurs through knowledge representation schemas that the learners hold in their minds. Piaget maintained that these schemas are organic and are continually enriched when one considers new experiences. Knowledge growth that occurs through re-organising learners' schemas lies at the heart of the constructivist learning theory. Principally, learners are not regarded as tabula rasa (blank sheets, empty jugs or vessels) that must be filled with knowledge by the teachers; rather, they construct their own knowledge. In the classroom situation, the constructivist view of learning can point towards various teaching practices. In the most general sense, it simply means a way of motivating all learners, regardless of gender, "race", religion and language, to use active techniques (experiments, real-world problem solving) to create more knowledge and then to reflect on and talk about what they are doing and how their understanding is changing. The knowledge learners construct in the choice of subjects will equip them for a better future.

Giroux's theory posited that, contrary to a repressive view of democracy as hyper patriotic and intolerant of dissent and doubt, one should embrace the value of a conception of democracy that is never complete or determinate and constantly open to different understandings of the contingency of its decisions, mechanisms of exclusion and operations of power (Habibis and Walter 2009). Both democracy and social justice buttress education for all. It is imperative to take cognisance of the concept of social justice, which places the spotlight on oppression and inequality in all its nuances. Moreover, it entails, but is not limited to, xenophobia and racism, economic discrimination and classism, misogyny and sexism, religious impetus and political persecution, the abuse of civil liberties and ableism, homophobia and heterosexism. The goal of a human rights-based approach to "education for all" is to ensure every learner receives a quality education that respects and promotes their right to dignity and optimum development.

Social justice factors are particularly important in an equitable curriculum because there is a dire societal need for global understanding. In fact, learners expect the school curriculum to provide them with a diverse education (Connell and Messerschmidt 2005). It is this diverse education that gives an understanding that each learner is unique and recognises individual differences. It is vital for schools to adopt practices and provide equal learning opportunities that focus on power and inequality issues, since the school curriculum is a developmental aspect for learners (Zajda, Majahnovich, and Rust 2007). It is worth noting that an equitable curriculum should ensure that all learners have an opportunity to achieve the highest possible standards, regardless of barriers some may face, and have equality of access to learning.

The apparent simplicity and rationality of this study of curriculum theory and practice, and the way in which it mimics curriculum management, are powerful factors in its success. Missing from the discourse surrounding the issue is empirical evidence of curricular mimicking, which is prevalent in the schooling system. Although comparisons indicate mimicking exists, there is substantial variation in curriculum coverage. A further appeal is made to academics who attack teachers as if they are the ones who are instrumental in an exclusive practice. The radical critiques are of two camps. The first are the de-schoolers (those who think that schools are worthless, useless institutions, which ought to be scrapped because their curriculum is meant for the chosen few in society); they want to de-school society (Illich1970). The first camp of radical critiques contends that

• The school curriculum in both capitalist and socialist societies is an instrument of oppression and monopoly.

• The school curriculum in today's specialised and consumer-oriented society serves to manipulate people. The consequences of schooling, what Dore (1976) calls the "Diploma and Degree disease", is a reflection of the manipulation of the educational system by market forces.

• Instead of being an equaliser, the school curriculum creates class difference and polarises society.

The second camp among the radical critiques are the neo-Marxists, who want to preserve the school as an institution, but want to reshape it to serve and match a society with a new order of production. Contemporary criticism about schools does not simply rest with differing reactions to the concept of schooling. It also involves disagreements as to what schools should be like and whether schools should provide equal educational opportunities. Coleman et al. (1966) asserted that equality of educational opportunity implies the provision of free universal education, an equitable curriculum for all learners, regardless of colour, gender, religion, and politics, and a common school system without dysfunction that is open to all.

In an equitable school curriculum, learners enter the classroom with their own specific learning needs, styles, abilities, and preferences. Teachers make standards-based content and curricula accessible to learners and teach in ways that learners can understand from their varying cultural paradigms (Kovacevic 2010). Oppression is both a reality and a perceptual phenomenon. It is further assumed that opportunities to exercise personal choice are desirable and liberating, that is, non-oppressive. Helping young people learn to make appropriate personal choices in schools is also assumed to be theoretically possible, operationally practical, and educationally desirable. If the schools are oppressive, choices will be restricted. If the schools are not oppressive, choices will be expanded. Critics have described educational practices that appear to be dehumanising. Protest groups have charged that schools are demeaning and restricting (Garwe 2014).

Someone must judge the merit of a school curriculum, determine how it is and is not meritorious, and the extent to which it is more meritorious than another. In a competitive market economy, consumers render that judgment-though, in a modern corporation, their judgment is somewhat diluted as it is translated into actual pay scales through the mediation of numerous intermediaries. Yet the bottom line is clear. A private school operating without government subsidy cannot pay its employees unless it satisfies the consumers with its products. The amount available to meet its expenses depends on how well it satisfies the customers (Mambo 2010).

Orwell's (1996) sad and cynical submission that all animals are equal, but some are more equal than others, becomes rather relevant here. It would appear that equal educational opportunity at its best is an ideal and a dream, and, at its worst, a political cliché, a consolation song to keep the poor hopeful (Freire 1972). Radical critiques of schooling often claim that the school curriculum reinforces class differences among members of privileged and disadvantaged groups in a society. The radical critiques view the concept of equal educational opportunity as a complex expression born out of the guilty conscience of an enlightened and privileged few individuals anxious to preserve their position of leadership without invoking social unrest and disaster (Miller 2004). From the government's point of view, equal educational opportunity is a tranquiliser to ameliorate the hopeless condition of the poor in society.

Liberal critiques of the school curriculum view the notion of equal educational opportunity in terms of economic resources available in the schools for teaching and learning, such as expenditure per learner, the availability of trained, well-paid teachers, lowering of the teacher-learner ratio, an attractive school environment and the provision of congenial physical facilities (Oduaran and Bhola 2006). There is, however, one criterion for the assessment of the school curriculum that is generally accepted by liberal and radical critiques, which is quality. Quality is a relative concept. In practical terms, the quality of a school curriculum can be defined with respect to several aspects of schooling that remain fairly constant over time. The concept of equity in a curriculum refers to the principle of fairness. Equity encompasses a wide variety of education models, strategies and programmes that may be perceived as fair, but are not necessarily equal. Equity is the process and equality is the outcome; given that, equity, what is fair and just, may not necessarily in the process of educating learners reflect strict equality- what is applied or distributed equally.

Methodology

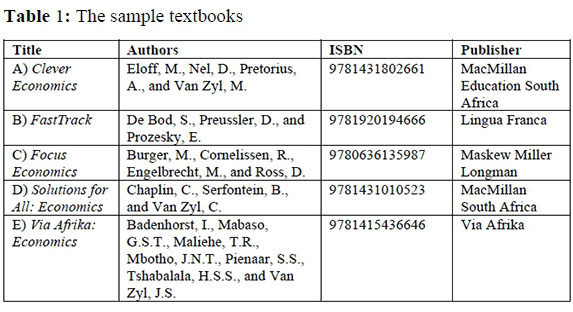

It became evident from the study that an inequitable curriculum is offered in some of the schools in the country. A qualitative approach was employed in data collection. A total of 16 South African schools were purposefully sampled, as reflected in Table 1. Two primary and secondary schools apiece were selected from the deep rural areas in four provinces, namely the Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal, Mpumalanga, and the Northern Cape. All the high schools were categorised under the gateway stream for National Senior Certificate Examinations (NSCE). The learner population was 64.3% females and 35.7% males. Of learners, 95% were from impoverished backgrounds and 5% from wealthy backgrounds. Approximately 60% of learners were black, while 20% were coloured, 15% were Indian and 5% were white. Cultural differences were not considered when teaching mathematics and physical science. The 80 participants in the interviews comprised learners, teachers and principals from the provinces mentioned above (see Table 1 for participants in the study).

Results

It has already been pointed out that participants were interviewed to derive the key findings. Based on these findings, it was apparent that there are wastage and stagnation in our schooling system, judging from learners' poor academic performance. In the Eastern Cape, the learners' massive failure in the National Senior Certificate Examination (NSCE) was viewed as part of societal failure, a society that shuns academics and worships mediocrity and materialism. The NSCE, the Annual National Assessments, and international standard test series in which South Africa participated all indicated weak and gravely differentiated academic performances by learners, especially learners in the public schools in South Africa. Jackson (2005) opined that only about 25% of South African public schools produce acceptable educational outcomes, and that among the 25% of schools, 15% of them are the former model C schools and the other 10% are made up of exceptional township and rural schools. Other factors identified in the study were the lack of instructional materials and facilities and the massive attrition of qualified and dedicated teachers in the schools because of the lack of promotion and incentives (Reddy 2003).

In the classroom observation, it was disheartening to see overcrowded classes where learners were still taught in dilapidated buildings with leaking roofs. In a classroom of 70 learners in Lusikisiki, with only 10 mathematics textbooks to be shared among all learners, surely, the standard of education will be affected to a large extent. This was exacerbated by the shortage of qualified teachers and laboratories for conducting physical science experiments. Where there were resources, they were distributed unfairly to certain schools. One wondered how some of the schools in the identified provinces had all the required resources that could boost the performance of Grade 12 learners, whereas in some there was nothing, in the true sense of the word. The poor infrastructure at many schools in the country was also indicative of the poor application of the school funding system. The concept of an equitable curriculum for all is just lip service from the Department of Basic Education because resources are grossly inadequate.

A similar study conducted in Nigeria by Oluwatobi et al. (2015) suggested that in most secondary schools in Nigeria, teaching and learning took place in the most unconducive environment, where there was a lack of the basic materials, which hindered the fulfilment of educational objectives. Although most science teachers in the rural areas did not have the necessary credentials to teach physical science and were less experienced and not as talented as teachers in urban areas, resources are still crucial for them to exhibit expertise in the subjects they teach. Without resources, the learning content is likely to be presented in a haphazard manner and learners will not benefit as the teaching becomes less effective. In a country where there are few jobs for those who are academically qualified, where the rich illiterate is the most venerated, where the most affluent is the least educated, where higher qualifications attract little if any remuneration, it is not surprising that the learners are becoming increasingly disenchanted with academics and disillusioned with the acquisition of unprofitable academic certificates (Mills 2008).

The recruitment of professionally unqualified and underqualified teachers into teaching has become an internationally acclaimed strategy to deal with teacher shortages, particularly in rural schools, as the demand is often more severe in these contexts (Carr 2001). When underqualified teachers are appointed in a school, it has a bearing on school results. The use of teachers with limited professional education has been linked to lower quality education and poor learner outcomes. Zaida, Majahnovich, and Rust (2007) opined that education in rural communities lags behind educational development in other parts of the country, despite the fact that the majority of school-age learners live in a rural setup. Classroom learning and pedagogical performance were severely hampered by a lack of teacher performance and pedagogical resources. Learners from KwaZulu-Natal expressed regret when they were denied access to an Indian school. The argument from the School Governing Body was that discrimination was fair because it was a result of the Hindu religion that is practised in that school. It is on this basis that one would advocate for fostering an equitable curriculum for all, without fear, favour or prejudice.

Discrimination on Various Levels

The current changes in government and the school system policies reflect an increased understanding that many learners are not as fully a part of the school community as expected. The global society is embarking on the adventure of accepting all learners as members of regular classrooms. The challenge in the 16 identified schools was to act on the knowledge to support teachers in accepting all learners and moving towards a more equitable educational future. This was identified in the Northern Cape schools, which struggled the most to mould the characters of the future parents and guardians and to realise equity and social justice for all. Teachers as change agents are beset with the task of teaching all learners, among whom are disabled learners or learners with special educational needs.

Gender Stereotypes

Gender bias in education is an insidious challenge that compels teachers and learners to react in a bizarre way. The victims of this bias from the four provinces had been trained through years of schooling to be silent and passive and were unwilling to stand up and expose the kind of harsh treatment they encountered. Principals further lamented a bad tendency among teachers to assume that certain gateway subjects, such as mathematics and physical science, were specifically meant for boys, while subjects such as home economics and needlework are meant for girls, because they are perceived as the weaker vessels. This kind of attitude affected girls psychologically to such an extent that they even performed poorly in the subjects in which they could excel because of an inferiority complex and a negative attitude they adopted.

A study by Gorski (2013) revealed that one consequence of socialisation is that boys and girls develop different attitudes to certain academic disciplines. It was hypothesised that negative attitudes influenced whether the learners would be able to engage with certain tasks and the subsequent quality of their performance. The prediction was that a negative self-concept would result in lower performance while a positive self-concept would result in excellent performance. Although all participants were interviewed separately, it was deduced that mathematics and physical science were crucial for their future.

Similar studies conducted in Korea by Ayers and Quinn (1998) exhibited that there is a correlation between attitude and performance. The different attitudes of both boys and girls altered the learners' levels of confidence, which, in turn, impacted their performance in the classroom situation. The different attitudes enhanced or depressed the performance of tasks, irrespective of achievement. Miller (2004), in a study on gender difference in attitudes towards mathematics in school, declared that there is a significant relationship between a learner's gender and their attitude towards mathematics. It was also established that the parents' view of mathematics influenced the learners' attitudes towards mathematics. All learners go to school with learning styles already developed, some of which are not different from those advocated in various subjects, but are incompatible with the learners (Cramme and Diamond 2013).

Schools that attempted to alter the curriculum to provide a "boy-friendly" curriculum not only exacerbated gender stereotypes, but caused learners to display suicidal behaviour. By playing to gender stereotypes, they reinforced the idea that only some activities and behaviours were gender appropriate, which limited rather than enhanced learners' engagement with the curriculum. What was required to deal with such attitudes was a whole-school approach of challenging gender biased cultures, which covered the school's ethos and its teaching practices.

The study further revealed that boys and girls experienced schooling differently and received different treatment from teachers. Learners from the girls' school were only allowed to register for needlework and physical education. Teachers encouraged them to focus more on the general stream of music, vernacular languages, and religious education. The research showed that the interactions between the teachers and the boys and between the teachers and the girls varied in frequency, duration, and content. Consequently, the boys and girls developed different perceptions of their abilities and relationships (Theoharis and Brooks 2014). This posed a challenge to teachers and principals, especially those in mixed schools. Teachers ought to treat boys and girls on an equal footing so that nobody feels better than the other in academic performance. Furthermore, the mode of socialisation led girls and boys to develop different attitudes to certain academic disciplines. The prediction was that negative attitudes will result in lower performance.

The teachers further divulged that as the girls grew up, they lost confidence in their abilities, expected less from life and lost interest in gateway fields of study and rewarding careers, specifically careers involving science-related fields. However, the focus on all girls as underachievers has been misleading. Principals argued that some groups of boys underperform at school and some groups of girls perform slightly better. Achievement gaps based on social class and ethnicity often outweigh those of gender and it is the interplay of these factors that impact the performance of girls and boys. It is sometimes assumed that girls as a group outperform boys across the curriculum, but in fact boys broadly match girls in all subjects (Westaway 2015).

All human beings are born free with dignity and rights. It is embarrassing and pathetic that females are perceived as soft targets for discrimination at several levels and in various domains (Miller 2004). The discrimination in the participating schools was damaging, derogatory and demeaning, and subjugated females as second-class citizens of this world. This treatment of women should be rejected at all costs. If a girl learner wants to pursue any field, the opportunity should not be denied by an inequitable curriculum.

With reference to teaching and learning, a socially cohesive approach recognises difference, although not to such an extent that difference itself becomes a source of division and differentiation between social groups. This does not mean that discrimination was not found to be endemic, structural, and inscribed in institutional cultures and practices. For instance, the bullying and discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersexual and questioning (or queer) (LGBTIQ) learners experienced in all the schools from the four provinces were overlooked. Stigma is a prejudiced attitude that perpetuates inequities and was readily applied to LGBTIQ and widespread insidious and pervasive stigma led to discriminatory attitudes and practices.

A frustrated learner bewailed this situation as follows:

The fact that I am a gay does not mean that I am not a citizen of this democratic country. I have my own right which should be respected. Teachers and learners should stop illtreating me as if I am not a human being. I enrolled at this school to study and nothing else. No one should dictate terms on how I should live because my parents accepted me the way I am.

The socialisation of gender groups in Eastern Cape schools assured that girls were made aware that they were perceived as unequal to boys. Every time learners were lined up by gender, the teachers affirmed that girls and boys should be treated differently, because they possess inferior and superior qualities. When a teacher ignored an act of sexual harassment, in a way it sanctioned the degradation of girls. When different behaviours were tolerated from boys but not from girls, because "boys will be boys", schools perpetuated the oppression of females. There was tangible evidence that girls were becoming academically more successful than boys; however, an examination of the classroom maintained that girls and boys continued to be socialised in ways that work against gender equity (Carr 2001).

Teachers socialised girls towards a feminine ideal by heaping praises on them for being neat, quiet, cool, and collected, whereas boys were encouraged to reflect on abstract ideas. Girls were socialised in the schools to recognise popularity as important and learn that educational performance and ability are not of paramount importance. As for girls in primary schools, those in Grade 7 rated popularity as more important than being dependent and competent. Through the interviews, it became evident that "nice girls" was considered a derogatory term, indicating an absence of toughness and attitude.

Racial and Social Exclusion

The findings manifested that racial discrimination and social exclusion were often ignored in the identified schools. In the language of apartheid planners, the concept of race refers to groups of people who have differences and similarities in biological traits deemed by society to be socially significant. People treat other people differently because of them (Miller 2004). Racial discrimination in the 16 schools was based on the concept of race; some "race groups" were privileged above others with regard to better service delivery in terms of education. Blacks, Indians, coloureds and whites received unequal treatment in schools. Discrimination in the conducted research reflected to a large extent the legacy of racial and social exclusion rooted in the apartheid era. The four identified provinces did not pay serious attention to it, partly because racism and discrimination were not only overt but also covert. Learners reported that covert discrimination was insidious and inscribed in everyday practices of the schools and it became the norm of life.

Most learners' concept of racial discrimination involved explicit, direct hostility expressed by learners towards members of a disadvantaged racial group. Yet discrimination included more than just direct behaviour, such as the denial of enrolment in a school due to a language barrier. Moreover, it can also be subtle and unconscious, such as nonverbal hostility in a tone of voice. Furthermore, discrimination against any learner was based on overall assumptions about members of a disadvantaged racial group that are assumed to apply to them, just like statistical discrimination.

Educational experiences of minority learners have continued to be substantially separate and unequal. Facilities and learning materials for learners attending white schools were totally different from those who were attending schools that were set aside for blacks. Of minority learners in the rural areas in KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape, 4% still attended schools predominantly well-established and well-funded outside the rural area. This figure was below those in other rural settings and provided the launching pad for scathing criticisms of what government had put in place to mitigate underperformance viewed in terms of academic outcomes.

Westaway (2015, 2) has, for instance, capitalised on such reports and posited the following:

A cruel irony here is that whereas Bantu Education was explicit in wanting to reduce black Africans to "hewers of wood and drawers of water", it actually did a better job (proportionally) in educating this grouping for skilled employment than the supposedly equal education regime of the democratic government.

Such conclusions are rather sinister given that liberal education philosophers would argue that the liberation of the mind is, in the first place, more important than just providing learners with daily bread. The study is not about the debates in this sphere of discourse for now. Surely, any mind that is circumscribed and warped cannot be in a position to work out the solution to the predicament that might have ruined the path of growth for a free-born black learner for so many years. In every tangible measure, from qualified teachers to curriculum offerings, the sampled schools mostly serving learners of colour had significantly inferior resources than the schools serving mostly white learners, as highlighted above. The research has shown that various aspects consistently influenced learners' performance to a certain extent. Learners perform better if they are educated in schools with a reasonable teacher-learner ratio than in overcrowded classrooms. It goes without saying that they also require a relevant curriculum offered by highly qualified teachers with a wealth of experience. It became apparent from the interviews that underprepared teachers were less effective in viewing all learners on an equal footing and they also had trouble with curriculum development and motivation.

Oduaran and Bhola (2006) and other scholars have continued to take a critical swipe at this phenomenon. The apparent consensus seems to be that the schooling system in South Africa is increasingly failing to measure up to standard. One negative comment after the other has been expressed in such a way that they have come to build up informed perspectives, some of which are not based on empirical research. The literature on the subject is replete with concerns over the very poor educational outcomes associated with schooling in South Africa. Curriculum quality and teacher expertise were found to be interlaced, because an equitable curriculum requires an expert teacher. The study conveyed that both learners and teachers were tracked to a certain extent. The most experienced teachers taught the most demanding subjects to the most advantaged learners in their mother tongue, while underperforming learners assigned to less able teachers received lower-quality teaching and less demanding material. Teachers of learners whose results were grossly inadequate were less likely to understand learners' learning styles, to anticipate their knowledge and potential difficulties, and redirect instruction to meet learners' needs. Learners who were taught in their mother tongue, such as Afrikaans instead of English, performed better than their counterparts. When tests and examinations were scored, learners from underperforming schools who were not taught in their mother tongue were more likely to fail.

A principal from a school in Mpumalanga expressed the following sentiments:

It is unfair to criticize Black and Indian learners when they fail examinations. Coloureds and Afrikaners have an advantage of studying everything from kindergarten up to PhD level in Afrikaans whilst their counterparts are not allowed to study in their own mother tongue. This justifies the high failure rate of blacks in schools and needs serious attention. Where is fairness in the democratic country?

A learner said:

We are from a Christian background and for admission to a Hinduism school, we were subjected to an interview based on that religion but unfortunately failed hopelessly. This was the closest school to our area and we could walk to and from within a few minutes. Apart from that results in this school are excellent. The government tried to intervene but unfortunately lost the case.

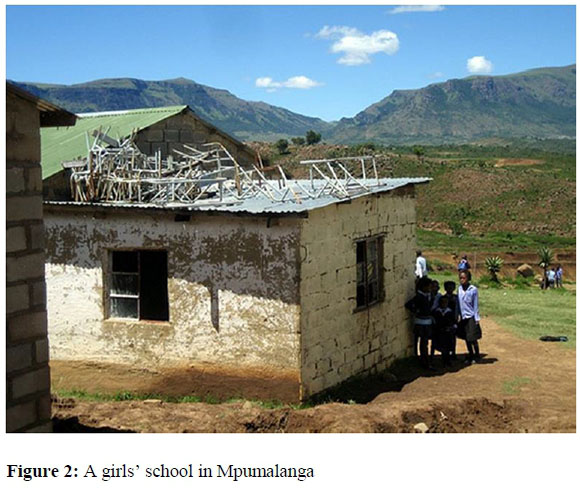

Laws and legal institutions must ensure that equal opportunities are provided for teaching and learning. The researcher had the opportunity to visit a couple of dysfunctional schools in the four sampled provinces in rural areas and the lack of resources in some of these schools was appalling, as portrayed in Figure 3 below. Some learners were only allowed to register at this school, which had a dilapidated building and no water and electricity.

In one of the schools in the Northern Cape (see Figure 3), conditions were so chaotic that it seemed miraculous that learning occurred at all, and much of the learning appeared to be haphazard because of a deliberate focus on the content and process of instruction. The ruling government spends a lot of money building prisons instead of funding education. Our tertiary institutions, like other levels of the school system, are starved of funds to the extent that they cannot adequately fulfil the role for which they were set up. Although there may be a number of factors impacting the curriculum, our universities still maintain an alien character in pedagogy and curriculum. This is a result of direct government intervention and control in the day-to-day management and running of our autonomous universities. Government's direct interference has inhibited the growth of our institutions of higher learning and the freedom to teach and to learn.

Discussion

The notion that social justice is concerned with the mitigation of deprivation and poverty reflects social justice's secular philosophical teachings on benevolence and charity that date back to antiquity. Social justice in this study was aimed at promoting a curriculum that is just, equitable, and values diversity. An equitable curriculum provides equal opportunities to all its members, irrespective of their disability, ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, language, or religion, and ensures fair allocation of resources and support for their human rights. The overall picture of social justice in the 16 schools portrayed in this study does not augur well for the future of our education system, and it is clear that something needs to be done to arrest the problem before it spirals out of control. Forms of discrimination in the identified schools cut across the rich and poor quintiles, fee and non-fee-paying schools and rural and urban schools. All the learners were in racially homogeneous, poorly resourced, and underperforming schools.

Despite South Africa's commitment to the promotion of a sound educational policy, the nation's schools are in a sorry state and have indeed failed to meet learners' expectations. We frequently hear that the quality of our schools is eroding. The truth of this statement depends on the indicator of quality used. If resource inputs and outputs of education are viewed as the sole indicators, the quality of our school curriculum appears to have declined.

Our schools also seem to have declined since an analysis of NSCE results in the past years have shown massive failure in schools, indicating that little or no learning seems to have taken place in our schools over time. Moreover, there is a dire need for improvement, especially in the secondary and post-secondary sectors, for learners with different levels of intellectual disability.

Conclusion

The study revealed that schools should be hospitals that nurture a more just society than the one we are currently part of. Unfortunately, too many schools are training grounds for boredom, alienation, and pessimism. Many schools fail to confront the racial, class and gender inequities woven into our social fabric. Teachers are often perpetrators and victims with little control over planning time, class size, and broader school policies, and much less control over the unemployment and other "savage inequalities" that help shape the learners' lives. For the curriculum to be more equitable, the School Management Team should endeavour to identify how resources and funds are being distributed and where inequities exist. They should also make a school equity pledge proclaiming the environment that will be created to ensure that equity is achieved. Moreover, there should be collaboration with community partners and parents to incorporate external interests and opportunities.

In conclusion, funding opportunities and revenue channels should be established to grow equity initiatives. An intricate global challenge that has become a bane in South Africa is to promote equal educational opportunity in schools. The concept of durable inequalities maintains that categorical inequalities exist via exploitation and opportunity hoarding. These asymmetrical relations between groups keep the disadvantaged bound to one tract and the privileged poised to continue reaping the benefits of their social resources. Whether consciously or not, people's positions on the social mobility ladder are largely fixed and as a result this perpetuates intergenerational cycles of poverty. These relational mechanisms sustain unequal advantage and amount to opportunity hoarding for the privileged group. The position an individual is born into hinges primarily on unequal control over value-producing resources. As for the most advantaged, they tend to own modes of production. It goes without saying that subordinated groups that result in further isolation of the disadvantaged view emulation through generations and adaptation as forms of coping.

References

Ayers, W., J. A. Hunt, and T. Quinn. 1998. Teaching for Social Justice: A Democracy and Education Reader. New York, NY: The New Press. [ Links ]

Carr, K. 2001. "Missing Out: The Politics of Exclusion and Inequality". Paper presented to Australian Fabians Society Conference, For the Rest of Their Lives, Education and Inclusion, Melbourne, March 30-31.

Coleman, J. S., E. Q. Campbell, C. J. Hobson, F. McPartland, A. M. Mood, G. D. Weinfeld, and R. L. York. 1966. Equality of Educational Opportunity. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. [ Links ]

Connell, R. W., and J. W. Messerschmidt. 2005. "Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept". Gender and Society 19 (6): 829-59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205278639. [ Links ]

Cramme, O., and P. Diamond. 2013. "Rethinking Social Justice in the Global Age". In Social Justice in the Global Age, edited by O. Cramme and P. Diamond, 3-20. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Dore. R. 1976. The Diploma Disease: Education, Qualification and Development. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Freire, P. 1972. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, NY: Herder and Herder. [ Links ]

Garwe, E. C. 2014. "Quality Assurance in Higher Education in Zimbabwe". Research in Higher Education Journal 23: 3-13. https://doi.org/10.5296/ire.v3i2.7288. [ Links ]

Gorski, P. 2013. Reaching and Teaching Students in Poverty: Strategies for Erasing the Opportunity Gap.New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Habibis, D., and M. Walter. 2009. Social Inequality in Australia: Discourses, Realities and Futures. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Illich, I. 1970. Deschooling Society: New York, NY: Harper and Row Publishers. [ Links ]

Jackson, B. 2005. "The Conceptual History of Social Justice". Political Studies Review 3 (3): 356-73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-9299.2005.00028.x. [ Links ]

Kovacevic, M. 2010. "Measurement of Inequality in Human Development-A Review". Human Development Research Paper 2010/35. United Nations Development Programme. Accessed May 30, 2020. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdrp_2010_35.pdf.

Lumadi, M. W. 1995. "Guidelines for a Relevant Education Curriculum at Teachers' Training Colleges." MEd thesis, Randse Afrikaanse Universiteit. [ Links ]

Mambo, M. 2010. Situational Analysis and Institutional Mapping for Skills for Youth Employment and Rural Development in Zimbabwe. Harare: International Labour Organization. [ Links ]

Mills, C. 2008. "Reproduction and Transformation of Inequalities in Schooling: The Transformative Potential of the Theoretical Constructs of Bourdieu". British Journal of Sociology of Education 29 (1): 79-89. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690701737481. [ Links ]

Miller, D. 2004. The Principles of Social Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Oduaran, A., and H. S. Bhola. 2006. Widening Access to Education as Social Justice: Essays in Honor of Michael Omolewa. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-4324-4. [ Links ]

Oluwatobi, S., U. Efobi, O. I. Olurinola, and P. O. Alege. 2015. "Innovation in Africa: Why Institutions Matter". South African Journal of Economics 83 (3): 390-410. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2460959. [ Links ]

Orwell, G. 1996. Animal Farm: A Fairy Story. New York, NY: Longman Publishers. [ Links ]

Piaget, J. 1964. "Development and Learning". Journal of Research in Science Teaching 40: S8-S18. [ Links ]

Reddy, V. 2003. "Initial Training for Permanent Unqualified Teachers through Distance Education Programs: South African College of Education as a Case Study". In Changing Patterns of Teacher Education in South African Policy, Practices and Prospects, edited by K. Lewin and Y. Sayed, 116-37. Johannesburg: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Theoharis, G., and J. S. Brooks. 2014. What Every Principal Needs to Know to Create Equitable and Excellent Schools. New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Vygotsky, L. S. 1986. Thought and Language. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press. [ Links ]

Westaway, A. 2015. "Towards an Explanation of the Functionality of South Africa's 'Dysfunctional' Schools". Paper presented to the Melon Media and Citizenship Group, School of Journalism, Rhodes University, May. Accessed May 30, 2020. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/1460/d056c89e9238ed0bf077576030c69d242cf5.pdI7 _ga=2.197740847.1485803714.1590651804-1665664073.1587099593.

Zajda, J., S. Majahnovich, and V. Rust. 2007. "Introduction: Education and Social Justice". Review of Education 52: 9-22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-005-5614-2. [ Links ]

^rND^sConnell^nR. W.^rND^nJ. W.^sMesserschmidt^rND^sCramme^nO.^rND^nP.^sDiamond^rND^sGarwe^nE. C.^rND^sJackson^nB.^rND^sMills^nC.^rND^sOluwatobi^nS.^rND^nU.^sEfobi^rND^nO. I.^sOlurinola^rND^nP. O.^sAlege^rND^sPiaget^nJ.^rND^sReddy^nV.^rND^sZajda^nJ.^rND^nS.^sMajahnovich^rND^nV.^sRust^rND^1A01^nRudzani Israel^sLumadi^rND^1A01^nRudzani Israel^sLumadi^rND^1A01^nRudzani Israel^sLumadiARTICLE

Turnaround learner discipline practices through epistemic social justice in schools

Rudzani Israel Lumadi

University of South Africa lumadri@unisa.ac.za https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9466-2854

ABSTRACT

Researchers claim that learner discipline has continued to be a problem in schools since corporal punishment was outlawed in public schools in South Africa. It is evident that teachers have a vital role to play in the improvement of learner discipline in schools. An interpretivist qualitative approach was adopted to investigate learner discipline practices as perceived by teachers in South African public schools. A sample of 10 (3 principals, 3 teachers, 3 parents and 1 learner) participants was used for the study. Social justice theory was used as a lens to consider the process of humanising learner discipline practices in terms of human rights. The article investigates how learner discipline practices can be turned around through epistemic social justice to influence the quality of teaching and learning in schools. The findings revealed that in South Africa there are no effective learner discipline practices. There is a need for education authorities to introduce compulsory training and development programmes for aspiring teachers to be equipped with new strategies to deal with learner discipline through a social justice approach. Social justice theory was used as a tool to address learner discipline practices in selected schools. It was recommended that there be more parent involvement in decision-making to consider a policy of transforming learner discipline practices to deal with the inequality and injustice in schools.

Keywords: turnaround; corporal punishment; school governing bodies; classroom discipline; cultural diversity; learner discipline practices; South African Schools Act; social justice

Introduction

According to research, there is a consensus that from a historical perspective the legal demand for the adoption and implementation of social justice policies still presents challenges associated with learner discipline in South African schools (Mpanza 2015). There are numerous published studies worldwide that describe the role of discipline as a possible tool for promoting quality education in schools (Gregory, Skiba, and Mediratta 2017). There is, however, limited research in the South African context with special reference to secondary schools on the implications of the social justice theory in terms of maintaining learner discipline and school functionality. In 1994, South Africa adopted the most important building block for establishing democracy based on the protection of the fundamental rights as enshrined in the Bill of Rights in line with global school disciplinary demands. As Woolman and Fleisch (2009) note, the values of human dignity, equal treatment and freedom are listed in section 7(1) of the Constitution. While this seems to be a noble idea, South Africa has continuously faced many disciplinary challenges in its schools such as bullying, school-based violence, gender-based violence, segregation, sexual abuse, physical aggression and emotional violence (Smit 2009). Of all the identified forms of indiscipline, researchers agree that bullying is the most serious issue being experienced on a daily basis in South African schools (Thornberg 2015). Although the South African Schools Act, No. 84 of 1996, in compliance with the Constitution, was introduced to replace the inequalities of the apartheid policies, including disciplinary policies and practices, learner discipline is still an unbearable problem, especially in terms of bullying (Amanchukwu 2011). There is also evidence of a negative relationship between undisciplined practices by learners and the quality of teaching and learner performance (Gregory, Skiba, and Mediratta 2017). The effective and efficient functioning of schools, the goal of which is to achieve quality education, is a nightmare under such circumstances, according to Amanchukwu (2011). With the aim of overcoming such challenges, this study investigates how learner discipline practices can be turned around through epistemic social justice to promote quality teaching and learning in secondary schools in the Vhembe district of Limpopo. The findings not only aim at contributing to the enhancement of social justice theoretical content, but also at the implementation and adoption of its principles and practices in the South African education system. The article sketches the background to the study, followed by the problem statement, aims and objectives and the literature review, which consists of the theoretical framework, conceptual framework and further discussion.

Background to the Study

The South African government invests in education with the expectation of producing a skilled labour force. Russell and Cranston (2012) claim that despite the investment, teachers, as highlighted in the introductory remarks, seem to be concerned about the prevalence of learner disciplinary problems in school environments, which result in a low standard of learner academic performance. Similarly, teachers play a significant role in improving learners' academic achievement and the social and moral development of learners in schools. Teachers could transform learner discipline practices through social justice theory in schools with the hope of fostering better educational performance (Russell and Cranston 2012). Central to this study is the assumption by the researcher that learner discipline is critical in the process of transforming and restoring social order.

Before identifying literature gaps in the context of this study, it is important to understand that epistemic social justice refers to the principle of applying fairness in terms of epistemological knowledge and understanding (Fricker 2007). In its opposite context (social injustice), the theory is aligned to the concept of epistemic injustice with reference to such terms as authority and power, suppression and knowledge and understanding (Fricker 2007). The epistemic justice theory, from a social justice perspective, was aimed at abolishing social inequalities (Petrie et al. 2006). It is also important to take note of the emphasis on the terms "knowledge" and "understanding". Social justice in schools is part of the underlying principles of social pedagogy, in accordance with the principles of equity (Rawls 1999). In order to live in a socially just world, all citizens need to be involved in protecting and promoting the values, principles and ideals of social justice (Nieuwenhuis, Aston-Jones, and Cohen 2005). In the context of this study, social justice is used as a possible tool to ensure that fairness is applied by eradicating power, oppression and any form of social inequality when it comes to learner disciplinary issues, and the focus is on knowledge and understanding as key principles.

Before digging deeper into more debates, the controversial issues to be tackled first include an understanding of whether social justice and democracy are the same. Woolmann and Fleisch (2009) claim that South Africa is not aware of the difference between social justice and democracy, according to the majority of educators, school management team (SMT) and school governing body (SGB) members interviewed for their study. What they found in most schools when it comes to disciplinary measures was autocracy, while democratic practices that lead to social justice were hardly practised.

Knowledge and Understanding of Social Justice and Democracy

According to Thompson (2015, 7), social justice fosters the perfect conditions for the rights, security, opportunities, and social benefits of every member of an organisation to be realised. In other words, democracy is a judicial requirement and an instrument for implementing social justice and vice versa (Xaba and Ngubane 2010). Research indicates that from a historical perspective, corporal punishment during the apartheid era was part of an authoritarian approach of managing the school environment, and discipline was based on the view that teachers should control learners (Porteus, Vally, and Ruth 2001). Injustice and unfair measures used to maintain discipline were reactive, humiliating, and punitive rather than corrective and nurturing (DoE 2012). Porteus, Vally, and Ruth (2001) contend that learner discipline in schools was often erroneously equated with punishment. Ugboko and Adediwura (2012) assert that learner discipline provides the order and structure needed to maintain the standard of expected learner behaviour in schools. The implication is that more knowledge and a better understanding of the principles of social justice and democracy can encourage a better understanding of appropriate principles and practices of social justice when it comes to disciplinary measures in schools. It is then necessary, in the context of this study, to suggest strategies to ensure that all education stakeholders have full knowledge and understanding of these principles for the successful implementation of disciplinary measures, including educators, the SMT, learners, parents, the SGB and the school community.

Misconceptions associated with democracy, social justice, and human rights have been found among many learners (Elam, Rose, and Gallup 1993). Some of them perceive democracy as protecting their right not to undergo disciplinary processes and relevant punishments for violating school laws (Elam, Rose, and Gallup 1993). For learners, democracy provides leeway for violence and bullying. Research has shown that this is one of the reasons why some of them react so violently to educators (Elam, Rose, and Gallup 1993). On the other hand, this misconception is a threat to teachers' security as disciplinary problems are at alarming levels in South Africa (Elam, Rose, and Gallup 1993).

Bearing this in mind, a strategy must be devised to address this issue through understanding learner discipline as an important part of the learners' behaviour- without it, the school will not be effective in achieving quality teaching and learning. Learner discipline allows the school to instil an environment conducive to learning for the school community.

Knowledge and Understanding of Bullying as a Form of Indiscipline versus Principles and Practices of Social Justice

There are also identified literature gaps between knowledge and understanding of causes of bullying and the appropriate strategies to provide a remedy. While some researchers associate causes of school violence and bullying with gender (Burger et al. 2015), others associate it with social norms (Goldsmid and Howie 2014). From a different perspective, some link bullying to wider contextual and structural factors (Goldsmid and Howie 2014). For instance, a study by Higson-Smith and Brookes (2001) reflects on gender inequality and the prevalence of violence against women in society. Similarly, social norms that support the authority of teachers over children may legitimise the use of violence to maintain discipline and control (Goldsmid and Howie 2014). This cannot be separated from the context of this study, since all the causes are linked to social justice policies, principles and practices in every aspect of life, including school discipline. "Proponents of social justice believe in the eradication of imbalances regarding gender, religion, socio-economic status, race or tribe" (Thompson 2015, 7).

Bullying versus the Teacher-Learner Relationship

According to Charles (2002), the last literature gap relates to understanding not only teacher-learner relations, but also the roles of the school management team, the SGB and the community at large. He explains there is a perception that only the classroom teacher is responsible for instilling discipline among the learners. This is probably because the teacher spends more time with the learners. However, the policy stipulations indicate that it is the responsibility of all educational staff members, the school management team, the parents, the SGB and the community at large, to instil good behaviour among learners. This is the reason why strategies must be put in place to ensure that all stakeholders have complete knowledge of the concept of full involvement in moulding the behaviour of school learners. In the same vein, teachers do not only teach knowledge and skills, they also help learners to define whom they are (Charles 2002).

Problem Statement

According to Elam, Rose, and Gallup (1993), learner discipline is viewed as a major problem for schools. It comes as no surprise that most disciplinary problems are caused by students (Elam, Rose, and Gallup 1993). There are identified knowledge gaps that seem to have escalated the prevalence of indiscipline, such as a lack of knowledge and understanding of social justice and democracy. Most consulted strategies have failed to combat these misconceptions of social justice, democracy and what the protection of human rights entails. This challenge is tied to gaps identified in the literature between knowledge and an understanding of bullying as a form of discipline and principles and practices of social justice (Elam, Rose, and Gallup 1993). Challenges associated with social injustice such as gender inequalities, racism, socio-economic status bias, religious inequalities, tribalism and power abuse can be discussed separately, but should not be separated when attempting to solve learner behavioural challenges.

Spaull (2013) confirms that globally the poor academic performance of learners could be attributed to a lack of learner discipline in schools. Teachers, students, school governing bodies (SGBs), and community members are not equally represented in the design of turnaround disciplinary procedures.

My study focuses on exploring the emerging trends and challenges that teachers encounter with learner discipline strategies to restore learner discipline. Turnaround learner discipline practices based on social justice theory reflect the contention that socially responsible actions and responses are learned in a culture where individuals are respected and well-integrated into a social network (Morrison 2001). The question remains how learner discipline practices can be turned around through epistemic social justice theory to foster quality teaching and learning in schools. The researcher proposes remedies that might bring social justice in classroom discipline in schools in line with the provisions of the South African Schools Act (SASA) (RSA 1996a) with regard to the effective and efficient management and discipline of learners. There is something wrong in schools when wealthy, low ability children overtake poor, high ability children. Teachers are the modern engines of social justice and need to continue with their mission to embed social justice in schools. The best means of translating intent into positive practice is to have good teachers for disadvantaged learners.

Given this background, this article argues that teachers do not seem to have the relevant knowledge to deal with the learner discipline they experience to enhance the school environment and learning conditions. It is likely to contribute to the body of knowledge in education and to inform practices and policy implementation. It is very important to reward learners for good behaviour and positive contributions to the school community. Effective learner discipline practices are used to turn around the school environment through consistency and teamwork. Moreover, there should be ongoing evaluation of school discipline practices and strategies for reducing classroom disruptions in view of academic achievement (Epstein 2011).

However, the quality of leadership makes a significant contribution to schools and learner outcomes, and it is recognised that schools require effective teachers if they are to provide learner discipline. Teachers can affect classroom management by adopting a proactive approach and becoming instructional leaders. However, sometimes the role of all stakeholders, including educators, SMT, SGB, the parents, the community and society at large, in moulding learners' behaviour seems to be neglected, resulting in another gap that needs to be addressed.

The identified challenges are common in secondary schools in the Vhembe district in Limpopo, which is experiencing a disciplinary crisis. For this reason, an investigation is required to come up with better strategies to turn around learner discipline practices in their own right within a specific terrain of public debate. This will help the principals, teachers, and parents to execute learner discipline practices effectively. Consequently, this article will outline turnaround learner discipline practices required to support the implementation of discipline that can be envisioned and included in the training of classroom teachers. Such an investigation requires that education policymakers examine turnaround learner discipline practices in their own right within a specific terrain of public debate.

The Aim of the Study

The main aim of the article is to investigate how learner discipline practices can be turned around through epistemic social justice to influence the quality of teaching and learning in the Vhembe secondary schools in Limpopo.

Research Question

This article is guided by the following research question:

• How can learner discipline practices be turned around through epistemic social justice to improve the quality of teaching and learning in schools?

Literature Review and Conceptual Framework

The key aspects, bullying and positive teacher-learner relations, inform the discussion. Discipline Practice

There is a consensus among many researchers that disciplinary practices relate to the actions taken by a teacher or the school organisation towards a student or group of students when they violate school rules (Dalporto 2013). While some researchers perceive the term "discipline" as referring to forms of punishment inflicted on a learner for breaking the rules, others put more emphasis on the aim of discipline as setting limits to avoid unbecoming behaviours among school learners that may harm other learners or that are against school policies, norms and ethics (DoE 2012). However, discipline is generally perceived as the provision of necessary guidance and support for children' s behaviour for them to be responsible and obedient not only in following school policies, but also to maintain principles of humanity at home and within society at large, among other people and the world around them (Dalporto 2013).

Epistemic Social Justice

In addition to what has already been highlighted, Fricker (2007) points out that in terms of power and the ethics of understanding and knowing, there are two kinds of epistemic injustice, namely testimonial injustice and hermeneutical injustice (Anderson 2005; Medina 2012). In the context of discipline in schools, Fricker asserts that testimonial injustice takes place when a person's knowledge and understanding are ignored or if they are ignored because the person is a member of a particular social group. This type of injustice includes aspects such as gender, "race", socio-economic, religious, and epistemic oppression. Hermeneutical injustice, on the other hand, occurs when someone's experiences in terms of poverty, family background, abuse or violations of other ethical values are not understood.

However, the key aspects of bullying, as a form of indiscipline, and teacher-learner relations inform the discussion in this study in the sections to follow.

Bullying

As highlighted before, teachers and learners describe bullying as a serious problem in schools.

Bullying is a social phenomenon that is established and perpetuated over time as the result of the complex interplay between individual and contextual factors (Thornberg 2015). To deal with ill-disciplined children, to reduce barriers to learning, and to increase participation of learners require insight into where these barriers may come from and why and when they arise. In support of this, Caravita, Blasio, and Salmivalli (2009) are of the view that it is very important for a teacher to be aware of the socioeconomic and family background of children to be able to understand non-academic factors that influence their learning. Many social factors that affect learning cannot be altered, but understanding these factors will enable teachers to see learners' "failures" in context and create learning environments that reduce, instead of increase, the effects of these factors (Cassidy 2009). Some teachers consider this a personal and professional challenge. The timing of teaching-learning interactions is part of learner discipline management. Learner indiscipline can be overcome by managing the classroom environment better and by improving the timing of classroom activities. Teachers tend to point out learners' deficiencies rather than praising them for their efforts and improvements. For many children, this is very discouraging and may result in them feeling inferior and like a failure. Effective teachers have learned and experienced that learner indiscipline is relatively rare in classrooms where learners are actively engaged and interested in the work and when they are appreciated for where they come from, whom they are, and what they are able to contribute (Ashworth et al. 2008).

Positive Teacher-Learner Relations

Positive teacher-learner relations and classroom environments are important factors that will have an influence on how learners experience school. In the same vein, teachers do not only teach knowledge and skills, they also help learners to define whom they are (Charles 2002).

From their daily interactions with teachers, learners learn whether they are important or not, bright or slow, liked or disliked. Teachers transmit these messages through their behaviour, gestures, and words. From the messages learners receive, they decide whether to risk participation in class activities or not. Spaulding (1992) contends that teachers must recognise that involvement may not always come easily and that this requires a trusting, psychologically comfortable classroom environment. The motivation to learn and to behave is based on interest. If teachers manage to stimulate curiosity among learners, they will also discover willingness among learners to learn and to behave. Teaching that satisfies learners' curiosity motivates them far more effectively than forcing them to perform tasks they consider irrelevant and boring. Therefore, the way teachers interact with and teach learners is crucial in preventing misbehaviour.

According to Charles (2002), despite efforts of positive interaction, bad behaviour may still occur and teachers must be prepared for this by using different techniques, ranging from counselling, focusing on understanding, or mutually solving a problem to ignoring inappropriate behaviour while reinforcing appropriate behaviour.

Research Design and Methodology

According to Blaikie (2000, 21), a research design "is an integrated statement of and justification for the more technical decisions involved in planning a research project [...] This process is analogous to the activities of an architect designing a building." In addition to the explanation, a research design focuses on the end product and all the steps in the process to achieve the anticipated outcome. A research methodology refers to the strategies applied in any form of investigation (De Vos et al. 2002). According to Creswell (2014), descriptive research aims to explain the type of phenomenon surveyed in this study. This study was conducted in six selected secondary schools in the Vhembe district and involved Grade 10 learners. An interview is an effective research instrument to get relevant information from the respondents if it is well prepared (Tuckman 1978).

A qualitative case-study research approach was employed to answer the question of how learner discipline practices can be turned around through epistemic social justice theory to improve the quality of teaching and learning in schools. According to Leedy (2013, 141), "a case study is used to study a particular situation in depth for a specific period". The qualitative research methodology was adopted because it allowed for interaction with participants, which enabled the researcher to construct their social reality. To achieve the aim of this study an interpretive, naturalistic approach was pursued to reach an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon under study. Three principals and three teachers from secondary schools agreed to participate. The qualitative research methodology was chosen because it derives meaning from the research participants' perspective (McMillan and Schumacher 2010). This is supported by Reaves (1992) who posits that qualitative researchers are primarily concerned with the process rather than the outcomes of the products. The qualitative research in this article focuses on how the turnaround of learner discipline in secondary schools will be attained. The researcher chose a qualitative paradigm because it facilitates inductive and descriptive research that commences with data collection and builds on the theoretical framework, which in this study is linked to the turnaround of learner discipline practices through epistemic social justice in schools.

Population

Okeke and Van Wyk (2015) refer to a population as a group of persons, objects or items from which samples are taken for measurement, for instance a population of dissertations and theses of postgraduate students. This study's population included principals, teachers, parents, and learners of secondary schools in the Vhembe district.

Sampling

By means of the convenience sampling method, six secondary schools in the Vhembe district were selected. This sampling method was used because the schools are easily accessible in terms of distance. Purposive sampling was used to select three principals, three teachers and three parents-nine respondents. The teachers were selected because of their daily learner discipline practices. Learners were selected as participants to gain their perceptions of disciplinary issues from their experience as the major victims. The role of the parents was to provide views on disciplinary issues from an educational and social perspective. The teachers' role is to maintain learner discipline from both an educational and social perspective. The principals, representing the SMT, provided perceptions based on their experience of interpreting and exercising disciplinary measures according to policy. In the context of this study, the SGB is considered as representative of the parents.