Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

On-line version ISSN 2222-3436Print version ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.16 n.5 Pretoria 2013

Financing gap in malaysian small-medium enterprises: A supply-side perspective

Shamshubaridah Ramlee*; Berma Berma

Faculty of Economics and Business, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

ABSTRACT

In Malaysia, the issue of financing gap in Small Medium Enterprise (SME) financing is common, but hardly discussed nor researched. The issue of financing gap or lacuna arises due to the mismatch between the demand and supply of institutional funds for SMEs. SMEs contend that finance for SMEs are abundant, however, the supply of bank financing is largely unavailable to them. Banks, on the other hand, maintain that lending to these SMEs remains low because of lack of qualified demand. This brought to the forefront the issue of financing lacuna; a perennial issue in many developing countries, including Malaysia. The objective of this paper is to discuss the financing lacuna in Malaysian SMEs, focussing on the supply side. This paper focuses on the supply perspective to fulfil the research gap in understanding the financing lacuna, which has often been overlooked due to the tendency to analyse financing lacuna from the demand side only. This has been based on surveyed data of SME entrepreneurs. This paper outlines the theoretical approaches and practices of SMEs financing in Malaysia, followed by an analysis of the factors that shaped the financing lacuna (gap).

Key words: financing lacuna, supply side, SMEs, risk profile, opaque borrowers, lending technology

JEL: G210

1 Introduction

The old adage, "all money is not the same" appears to hold some truth for small-medium enterprises (SMEs) financing in Malaysia. SMEs contend that finance for SMEs are abundant, however, the supply of bank financing is largely unavailable to them. Banks, on the other hand maintained that lending to these SMEs remains low because of lack of qualified demand. The government has also spent huge sums of money to support the development of SMEs and this is reflected by the proliferation of loans, grants, guarantee schemes, venture capital and government loan schemes targeted at SMEs. Yet, financing continue to be one of the key development constraints cited by the majority of SMEs. There is a mismatch between demand and supply of funding for SMEs or a funding lacuna (gap).

The SME funding lacuna is a perennial problem but rarely subjected to open discussion or academic research in entrepreneurship funding literature (OECD, 2007 Vol. 1 & 2). Undeniably, there is much literature dealing with financing of SMEs at home (Ndubisi & Salman, 2006: APEC, 1994: SMIDEC, 2007) and abroad. Many of these studies focused on sources of capital, capital structure and financing constraints. But few of them investigate SMEs' ability to borrow from financial institutions and the reasons preventing these institutions from lending to SMEs as compared to large-scale enterprises. In Malaysia, the discussions and research on SME funding are often focused on the problems SMEs faced in obtaining institutional funds (demand-side). There is, however, very limited research on the determinants of funding to SMEs from the financial institutions' perspective (supply-side). This lack of academic research is partly due to the difficulties in collecting hard data of clients and practices from the financial institutions due to the non-disclosure legal requirements.

This paper is one step aimed at bridging this research gap by discussing the SME funding lacuna. The objectives of this paper are to discuss the funding lacuna in Malaysia by focussing on the mismatch between the demand and supply-side issues of SME financing. The paper will also highlight the policy responses to address SME funding issues. It also provides a synthesis of selected supply and demand side issues which contribute to the SMEs funding gap.

This paper is organised into four sections. Following section one which serves as the introduction, section two defines the conceptual framework of the SME funding gap and the theoretical issues in the demand and supply of SME funding. The SME funding lacuna in Malaysia is discussed in section three. The section begins by briefly discussing the demand issues in SME financing, which is followed by an in-depth discussion of the supply-side issues. It also highlights some of the policy responses adopted by Government to address the demand and supply-side constraints faced by SMEs. Finally, section four presents the conclusions.

2 SME funding gap: conceptual framework

This section outlines the theoretical underpinnings that frame the discussion in this paper. SME financing constraints using the financing gap hypothesis are considered.

Generally economics has given little attention to small firms. If markets are efficient and information is complete, the size of the company has no effect on its ability to raise funding, for there will be a price that covers the risk. These assumptions have since been challenged. Many studies have reported that smaller enterprises experienced higher financing obstacles along the capital structure spectrum than larger enterprises (Wattanapruttipaisan, 2003; Beck, 2007; Beck & Demirguc-Kunt 2006). Studies also show that smaller firms' financing obstacles have almost twice the effect on their growth as larger firms' capital constraints. Banking systems systematically underserved the SME sector relative to larger firms. Export, leasing, and long-term finance are also scarcer for SME firms. This situation cannot be fully explained by one single reason; it is necessary to explain it from both the demand and supply side. While the supply side focuses on the issues affecting the institutions involved in providing finance, the demand side focuses on issues affecting the SMEs seeking capital.

2.1 SME funding lacuna: the demand-side perspective

This section discusses the issues from the demand side in obtaining finance. One of the major challenges confronting SMEs is accessing financial resources, particularly at their seed, start-up and growth. Most research on SME financing cited background of SME borrowers, fund availability and accessibility as the key factors shaping the SME funding gap. This study extends the discussion by examining other key elements derived from information asymmetry problems.

For a start, it is important to define the access problems. The issue of SME access to finance has long been the centre of academic research. The majority of this research agreed that it is "not easy" to define the access problem. Some analysts (Claessens, 2006; Murduch, 1999) have provided specific definetions to access to financial services by classifying them into different dimensions The dimensions are availability, (are financial services available, and if so in what quantity); cost (at what total price are financial services available); and range, type, and quality of financial services offered. Murduch (1999) on the other hand, identified the access dimensions as being related to reliability, (whether finance is available when needed); convenience, (is access easy); continuity, (can finance be accessed repeatedly); and flexibility, (are products tailored to individual needs).

A common theoretical argument for the finance gap is information asymmetry leading to credit rationing on the part of bank lenders (Berger & Udell, 1998; Petersen & Rajan, 1994). Information asymmetry arises due to imperfect market conditions; the relatively low levels of accountability of credit, compounded by poor bookkeeping records; the absence of credible collateral; a lack of transparency; and risks that arise due to the specific markets that SMEs operate in. To the suppliers of funds, the SME market segment is "high risk" because small loans are risky. Banks are reluctant to provide credit to SMEs, whom they perceive as their riskiest clients, potentially providing insufficient profit margins and high transaction costs compared to large firms.

Some also argued that micro and small enterprises are not financially sophisticated enough to participate in the formal financial sector or cannot afford market interest rates and therefore require government or donor-funded credit subsidies. Hence mainstreaming the SMEs will require government intervention and the overall macroeconomic legal, regulatory and financial framework must be in place to ensure SMEs' access to finance (OECD, 2007).

2.2 SME funding lacuna: the supply-side perspective

The difficulties standing in the way of flow of institutional funds to the SME sector relate to a host of systemic and institutional barriers cross-cutting supply-side issues. From the supply-side, the constraints include, but are not limited to, cost-effectiveness of loans to SMEs, opaqueness of borrowers, transaction costs, information, including lending technologies to assess credit applications. The implication of these constraints is that the proportion of loans allocated to SMEs receiving bank loans is very low.

First, there is the cost effectiveness of loans to SMEs. This issue is related to the scale economies in lending. The higher the loan amount, the lower the lender's inspection cost per unit of loan, and the lower the borrower's unit cost of providing information, filling out forms, etc. Because there is a correlation between loan size and firm size, regardless of firm quality, scale merits mean that large loans receive precedence over smaller loans. Also, the operating costs of SME finance institutions are high. This results in their inability to easily achieve profitability and even if they do, their margins are relatively lower than other formal financial institutions that do not cater to the SME sector.

Next, information economics highlight the imperfections involved in small firm lending. Some argue that banks do not find SMEs to be profitable due to the high transaction costs and institutional risks arising from asymmetric information between borrowers and lenders; the borrower has private information about the firm that the lender doesn't have. For SMEs, because of their small size and obscure accounting, the extent of information asymmetry becomes more serious. Incomplete information in terms of creditworthiness and interest rate evaluation of a small firm triggers a "lemon" problem equivalent to that in the car market (Akerlof, 1970). The lender cannot fully determine how risky the borrower is, and cannot monitor the borrower once the loan is furnished. This causes problems of adverse selection and moral hazard.

The SMEs are characterised by informational opacity. This can be attributed to the fact that they are typically new entrants to the formal sector and lack any credit history or formal records. Even where they keep records these are mostly incomplete or inaccurate. The relative opacity of the SMEs target group results in relatively higher transaction costs when lending to this sector. Asymmetric information results in adverse selection and moral hazard, which are two factors that contribute to credit rationing. This is well-documented and evidenced in monetary economic literature (Diamond & Dybvig, 1983). The costs of assessing and processing loan applications are identical for large and smaller loans, and micro-enterprises require relatively smaller loans than larger enterprises to start or expand their businesses. To reduce the fixed cost element arising from loan assessment, tiered interest rates are used. This involves charging higher nominal interest rates on smaller loans i.e. loans offered to the SME finance target group.

The argument on SME's opaqueness is further supported by Stiglitz and Weiss (1989) who argue that the selection of borrowers in the loan market are more difficult, as rationing credit will enhance the adverse selection and moral hazard problems among borrowers. Information asymmetry on borrowers' repayment abilities increase banks risk of selecting borrowers. With higher interest rates charged, suppliers of credit are attracting a riskier group of borrowers who will be attracted to invest in higher risk projects. This higher risk projects in turn provide higher profit incentives among borrowers, hence necessitating higher monitoring efforts due to moral hazard problems.

Higher risk perception among credit supplier are not without evidence. Research and practices in small business lending often revealed that borrowers are highly opaque.

They have either no or limited track records as a result of a short business history. This fact accentuates the adverse selection problems among borrowers as identifying bankable prospect is difficult. Lack of business plans aggravate the negative risks perception of credit suppliers, as road maps for the growth of borrowers are difficult to determine (Wattanapruttipaisan, 2003). This translates into an unconvincing financial forecast and eventually difficult repayment performance.

Studies (Berger & Udell, 2002; Hirofurm, Nobuyoshi & Udell, 2006) also revealed that financial institutions do not use appropriate financial technologies necessary for appraising and monitoring microfinance credit applications (Berger & Udell, 2006). Generally, the provision of financial services in general and SMEs in particular involves an assessment of the probability that borrowers will keep their promises to repay the principal and interest on time, and, in the case of micro-enterprises, have the experience to run a particular operation. This function is performed by credit officers. Unfortunately, a constant finding in many surveys aimed at assessing the quality of SME finance staff is that they have limited if any previous experience in credit. This situation is exacerbated by the fact that the small-scale finance target group typically lacks any credit history or complete records, as highlighted in earlier paragraphs.

This relates to the issue of lending technologies discussed by Berger and Udell (2006). They used the differences in lending infrastructure to explain the financing problem faced by SMEs. They argued that large institutions have a comparative advantage in transactions lending based on "hard" information, which include financial ratios and credit scores. This information is relatively easily observed, verified, and transmitted.

On the other hand, banks targeting small enterprises have a comparative advantage in relationship lending based on "soft" information, which focuses on the character of the SME owner, and his knowledge of the local community. This information is not easily observed, verified, and transmitted. Studies, however, revealed that banks often based their SME credit decisions more on strong financial ratios (hard information) than on prior "soft information" which characterises SME borrowers (Cole, Goldberg & White, 2004). The implication of this argument is that what matters is not just the number of banks providing funds to SMEs but equally important is to address the issue of SME opaqueness, and providing funds that are well-suited for opaque SMEs. Berger and Udell (2002; 2006) suggested that "better" lending infrastructures can make significant differences in SME credit availability, directly through facilitating the use of the various lending technologies, namely financial statement lending, SMEs credit scoring, factoring, and asset-based lending.

This section has provided the conceptual background for the discussion. The following section discusses the SME funding lacuna in Malaysia. It begins by briefly considering the funding gap from the demand perspective, followed by a detailed analysis from the supply-side.

3 SME funding lacuna in Malaysia: excess supply versus unfulfilled demand

In Malaysia, the SME sector has been one of the key drivers of the nation's economic growth. The SME sector has two important roles to play. First, SMEs are the thrust of Malaysia's economic policy. It strengthens domestic demand, promotes and diversifies endogenous sources of growth, and infuses dynamism into the economic sectors. Second, SMEs are impetus for broad-based economic growth. They provide linkages between sub-sectors in the Malaysian economy. They are the source of dynamism and agility. The SME sector also serves as a seedbed for indigenous entrepreneurship. It has long been recognised that a vibrant SME sector results in a broad and diversified domestic production base, stimulate Bumiputera entrepreneurship, promote the development of local technology and contribute to the achievement of macro objectives such as full employment, poverty alleviation and equal income distribution (SMIDEC, 2002; Ninth Malaysia Plan, 2005).

To have a better understanding of SME funding lacuna in Malaysia, the following section discusses this issue from the supply and demand perspective. Figure 3 shows a graphical representation of SME funding in Malaysia from the supply and demand perspectives.

3.1 SME Funding: unfulfilled demand

From the experiences of policy makers and practitioners it has been realised that the SMEs are often plagued by constraints. These restrictions, however, are not unique to Malaysian SMEs, but rather a worldwide phenomenon. The SMEs are constrained from achieving economies of scale in the purchase of inputs like equipment, raw materials, finance, and consulting services. They are often unable to access global markets and are limited in their performance in increasingly open, competitive domestic markets. Because of their size, it is difficult for the SMEs to access functions like training, market intelligence, logistics, and technology. As such, they are unable to take advantage of market opportunities that require large volumes, homogeneous standards and regular supply. Furthermore, enterprises compete not only on the basis of prices, but also of their abilities to innovate or upgrade. Improvements in product, process, technology, and organizational functions such as design, logistics, and marketing have become the critical success factors in firm competitiveness in a globalizing economy. The SMEs are thus under pressure to innovate and upgrade their operations in order to participate in international markets. However, they often lack the financial resources to do so.

The Malaysian Government has taken various steps to solve deficiencies in this sector and alleviate constraints that affect it. Given its significance and potential as a driver of economic growth, the Government has developed and implemented various development programmes, and allocated significant funds and resources to further enhance the growth of this sector. In 2010, banking and financial institutions, comprising banking and non-banking institutions, approved RM 62.6 billion to more than 140,487 SME accounts, an increase of almost 60 per cent from the year 2006. As of 2010, RM 9.65 million has been allocated to the BNM Special Funds and Guarantee Schemes.

The Government allocated RM 37.22 billion to 83 schemes while the Credit Guarantee Schemes approved RM 48 billion to 410,000} SMEs. Forty one financial institutions utilise the credit bureau services, while 28,230 non-banking financial institutions use the credit information provided by the SME Credit Bureau, reducing the opacity information of borrowers. Other funds RM 5.6 billion from venture capital, RM 120 million from pawn broking and ArRahnu and RM 776.3 million (or 57,403 accounts) from microfinance institutions. Figure 2 provides us with the funding landscape for SMEs in Malaysia in 2010.

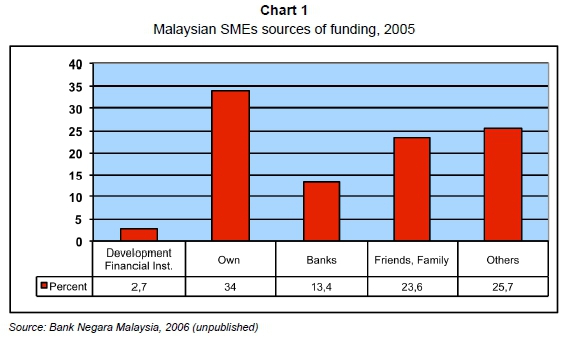

In spite of Government's priorities and efforts, certain segments of the SME sector continue to lament the lack of financing access, which is deemed a major challenge that hinders their growth and development. In fact, access to financing has been identified in many business surveys as one of the most significant obstacles to the survival and growth of SMEs including innovative ones. As Chart 1 shows, the majority of SMEs (only 13.4 per cent) rely on banks and 2.7 per cent on development financial institutions to fund their business (latest published data was not found).

The commonly-cited lack of accessibility to institutional funding is timeliness of approval and disbursement. Studies (Shamshubaridah, 2005; Shamshubaridah & Berma, 2008; 2009) showed that loan approvals and disbursements take more than 3 months for SMEs and the time taken becomes longer for smaller-sized loans. Banks are seen to be not 'user friendly' as tedious processes are involved when applying for loans and disbursements. Long processing time in validating information from borrowers' proposal or business and difficult pre-disbursement conditions, often leave the borrowers with a tight cash flow position (Shamshubaridah & Berma, 2009).

Smaller enterprises as compared to larger enterprises in Malaysia (SMIDEC, 2002; Bank Negara, 2005; Shamshubaridah & Berma, 2008; 2009) experience higher financing obstacles along the capital structure spectrum. Moreover, limited market power, the lack of management skills, high share of intangible assets, the absence of adequate accounting track records and insufficient assets, all tend to increase the risk profile of SMEs. Consequently, traditional commercial banks and investors have been reluctant to provide financing services to SMEs (SMIDEC, 2007). In contrast, larger enterprises with better business plans, more reliable financial information and larger assets have an easier time in obtaining finance through traditional means.

Ismail & Siti (2008) reported the current financing practices and problems of technology-based small and medium enterprises in Malaysia. They showed that, in addition to entrepreneurs' personal savings and profits retained in the firms, most Malaysian SMEs have approached external sources to finance business development. Enterprises that use external finance rely heavily on debt finance. This empirical evidence confirms enterprises "pecking order theory" as most of the enterprises follow some order of financing preferences. These studies look into the types of financing available at different stages of development namely the seed stage, start-ups and growth as well as the funds that have been made available. The financing amount allocated among sectors, the types of loans (working capital, term loans, revolving credits etc.), and types of instruments, are largely reported to show the extent of financing efforts by the government.

Other studies look at how SMEs face challenges in the global and domestic market in an environment of financing constraints (Ndubisi & Salman, 2006). The most important obstacle in making loans more accessible to any borrower is the information asymmetry between the borrowers and the lenders, where borrowers have private information about the firm that the lenders do not have. The small size and usually having a short business history, obscure accounting, and a lack of business plans, makes the problem even more pronounced for SMEs. In the case of Malaysia where funds availability is never an issue, the lenders have been left with a dilemma to fulfil its role both as profitable and developmental financiers (Shamshubandah & Berma, 2008, 2009). Rationing credit by limiting the loan amount or increasing interest rates are the solutions to limit the risks of lenders. However, national developmental objectives (such as the need to target SMEs in priority sectors and ethnic background) often constrain lending institutions from taking the necessary measures to reduce the asymmetry information faced. Given the risky profile of the SME borrowers that need to be served, the regulatory environment in which lenders operate and the transaction costs incurred when using lending technologies, we discuss below how loan accessibility from the suppliers' perspective has been a perennial complaint among the SME borrowers.

3.2 SME funding: excess funds

This section discusses the issues of SME funding in Malaysia from the supply perspective. It complements the earlier discussion by analysing the key elements that shape financial institutions from funding SMEs. The discussion focuses on three key aspects: environment, risk and transaction cost.

3.2.1 Environment

The economic and business environment in Malaysia shapes the supply of funds to SMEs. The environmental factors include the regulatory requirements, and loan monitoring and collateral requirements.

Lending institutions worldwide operate within a regulated environment to ensure a smooth flow of funds from the suppliers' and the demanders' side amidst the imperfect market where asymmetry information is at its highest. Fragility of the financial system has stimulated central banks to a tighter supervision. Fear of financial crisis and its spill-overs to the real sectors has given rise to the wider powers of the central banks worldwide. Controlling the rise of non-performing loans and deterioration of loan values has prompted the tight control of banking and its functions.

Malaysian financial institutions are governed by the Banking and Financial Institution Act 1989 and Development Financial Institution Act, 2002. Laws regarding the granting of unsecured loans (Section 60, BAFIA) and monitoring of loans and credit limit to single customers (Section 61, BAFIA) shape the delivery, hence the accessibility of loans. Implicit prohibitions to offer loans to potential borrowers without collateral, and collateral monitoring requirements, have influenced the lending technology practices. It is not unusual for financial institutions to insist that loans be secured against other assets and third party guarantees. Problems become more acute when applicants for loans are small borrowers with no track record and a short business history, where accumulation of assets that could be pledged to banks are almost impossible.

In Malaysia, single borrowing limit requirements, measured by the gearing ratio of SME borrowers, have resulted in credit suppliers limiting loan exposure amounts to prospects. Efforts to maintain a favourable gearing position is also one of the ways to ensure that credit quality of institutions do not deteriorate adversely. Often borrowers are given loans in accordance with the amount of internal savings or other contributions that has been put into the borrowers' businesses. As SMEs do not have the luxury of an internal source of funds, efforts to furnish evidence to suppliers of credit on their contribution to the business, often entail a long negotiation process. In most adverse situations, it is not uncommon for credit applications to be rejected or, if approved, leading to a longer period of loan disbursements.

Government intervention efforts to develop sectors by channelling credits to various institutions, forces credit suppliers to incorporate collateral as a screening device (Gale, 1989) In some cases, government development initiatives to develop indigenous groups through the Bumiputera Commercial and Industrial Community Programs (BCIC) requires the channelling of funds through the various non-bank financial institutions (see National Development Plan, 1990). Accessing loan viabilities are even more acute for certain suppliers, since risk profiles are even more severe, especially among the new Bumiputera enterprises. Often these ethnic borrowers have the assets to be pledged but have difficult asset conditions that may restrict banks from taking it as collateral. Restrictions on landed properties such as a 'Malay Reserve' land status, may make fulfilment of loan conditions difficult. Shamshubaridah (2005) and Shamshubaridah & Berma (2008, 2009) found that banks took longer to disburse a loan to Bumiputera borrowers, as land offered for security purposes to the banks are not able to attract an attractive forced sale value, due to the restrictions inherent in the type of land.

Efforts to make funds more accessible among SMEs are often interrupted by the very opaque nature of the borrowers. Although loans are abundant across sectors with varied purposes, lack of quality information as to the bankability of the borrowers forces the credit supplier to institute standard best practice procedures. Loan monitoring conditions through various covenants for pre and post disbursements are essential. Pre-disbursement conditions such as changing the type of land from agriculture to commercial are the most common way to ensure that assets are of value and used as security. The process however, requires long processing time with the land office department. This in turn affects the swift fulfilment of the loan conditions and hence interferes with the loan disbursement. Hence the timely accessibility of the loan.

In a situation where land is already able to be changed, ascertaining the land value is yet another problem. Lack of funds on the borrowers part to engage in valuers to determine the land value also affect loan delivery timeliness. Hence, it is not unusual for commercial or developmental credit suppliers to protect themselves by having a client charter. The charter will specify the suppliers claim on its timely delivery according to the borrowers timely efforts to make the assets chargeable (Shamshubaridah, 2005).

The establishment of the Credit Guarantee Corporation (CGC), helped to address the issue of shortfall of asset value of financial institutions, arising from the lack or insufficiency of collateral among borrowers. The main objective of the CGC is to assist SMEs with no track record or collateral, or inadequate collateral, to obtain credit facilities from financial institutions by providing guarantee coverage for any loan facilities demanded. The request for a guarantee facility however, requires another process that needs to be entered into by the borrowers. Credit suppliers' loan considerations are still dependent on the success of the loan guarantee applications. It is therefore not unusual for banks to take considerable time to assess loan applications and slow loan drawdown.

3.2.2 Risk

The perception of the supplier of funds towards SMEs is one of the determinants of fund allocations to SMEs. The opaque nature of SME borrowers in Malaysia is not an exception when a financial institution enters into a lending relationship. Asymmetry information regarding borrowers' projects, businesses and promoters' profile is high. Credit rationing in the form of high interest rates and lower loan approval amounts are hence inevitable. Specialized financial institutions such as SME Bank Bhd., EXIM Bank, MIDF, are often the target for an external financing source among Malaysian SME borrowers. The experiences in Malaysia concur with the issues that were discussed by Stiglitz and Weiss (1981).

Efforts to reduce the risks perception among suppliers of credit include the establishment of credit bureaux such as the SME Credit Bureau Malaysia. This is to provide credit profiles of potential borrowers and help in reducing the risk perception arising from asymmetry information; which translate into better credit input that can be used by banks to process an application. Efforts to securitize SME loans through the establishment of the National SME Development Council will enable banks to diversify its credit risks (Omar, 2006). This will increase the lenders tolerance for risks, which will result in banks becoming more realistic when devising loan covenants, hence speeding up loan drawdown and improving accessibility.

The establishment of the SME Bank Berhad and Microfinance Institutionare is an attempt by Malaysia to correct the risks profile of the SME borrowers. With an added corporate advisory services function, consultation given to coach clients in maintaining records and building business plans, will help reduce the opaqueness of the borrowers. Formation of a SME Special Unit in Bank Negara Malaysia further helps to speed up loan accessibility. The SME Special Unit is to assist the SMEs in the following areas:

• provide information on the various sources of financing available to the SMEs;

• facilitate SMEs in their loan application process;

• address difficulties faced by viable SMEs in securing financing; and

• provide advisory services on other SMEs financial requirements.

This special unit is part of the on-going efforts to ensure continued access to financing for viable SMEs across all sectors

3.2.3 Transaction costs

Making loans more accessible is not without a cost for the lenders. Although loans are highly subsidized with minimal funding costs for lenders, lending to various sectors with a variety of purpose, make the loans accessibility more challenging and problematic for the banks. Higher cost to process credit is inherent in the lending technologies adopted. Hard information about lending, through the use of financial statements and fixed assets of borrowers, are almost impossible in most Malaysian SME borrowers. Standard credit scoring instruments as commonly adopted by Malaysian lenders to evaluate applications, are difficult to be used among these SME borrowers as information is difficult to quantify (Shamshubaridah, 2005). Lenders have to complement hard information lending with the use of soft information technology that is through the use of relationship lending approaches.

In the relationship lending technology, information on the riskiness of borrowers is obtained through years of information accumulation. These long years of relationship enable lenders to collect psycho graphics information about borrower's repayment abilities. It is common for loan officers to maintain personal working relationships that may interfere with the professional demand of the job functions. Efforts to use relationship banking apart from the financial statements and fixed asset lending methods translate into costlier processes that will increase the transaction costs.

In terms of spatial, it is necessary to analyse the extensiveness of bank branching and its impact on the transaction costs. In Malaysia, although high investments in technology may provide the economies of scale advantage, processing loans and disbursement procedures may still increase the cost to make loans more deliverable. Loan application and disbursement requirements from branch offices are cases in point. Approval for both the former purposes requires the Head Office subsequent and final approval. These translate into higher transaction costs for the lenders as the work of the branch officers need to be verified and therefore limiting the speed of loans accessibilities. This practice is even more critical among highly opaque SME borrowers.

The scale of operations for banks refers to the size of loans extended to borrowers. As has been discussed, smaller loan size borrowers present a higher per unit cost of processing compared to a bigger size loan. This is due to the processing nature of loan applications and disbursement requirements. In fact, the smaller the loans the more tedious the processing time as the opaque nature of borrowers requires more time for lenders to verify and process an application. Studies by Shamshubaridah and Berma (2006) revealed that it took more than 90 days for small and medium size loans to be processed before a lending decision is obtained. Enabling a speedier loan disbursement for small sized loans among the SME borrowers is also difficult. In some cases loans are not even disbursed as borrowers are unable to fulfil the pre-disbursement conditions stipulated by the lenders (Shamshubaridah & Berma, 2006).

4 Conclusion

Financing has always been a perennial problem among Malaysian SMEs. Many studies have been done to analyse the problems of SME financing. The most common approach is to analyse SME financing problems from the demand-side. The most commonly cited problems are the opaque profile of the SMEs, business and promoters background, fund availability and accessibility. This paper attempts to fill the research gap on SME financing by discussing the supply-side focussing on the practices of the supplier of credit, the environment that influences the supply of funds to SMEs, the risk that the supplier of funds incurred by servicing SMEs, and the high transaction cost involved in delivering credit to SMEs. This paper is an initial attempt at filling the research gap on SME financing lacuna (gap) in Malaysia. It opens new agendas for academic research and debates on the issues of fund accessibility among SMEs; the engine of Malaysia's economic growth

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the valuable comments made by the reviewers.

References

AKERLOF, G.A. 1970. The market for 'lemons': quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3):488-500. [ Links ]

APEC. 1994. The APEC survey on small and medium enterprises: member report of Malaysia. Available at: http://www.actetsme.org/archive/smesurvey.html [accessed 2008-06-14]. [ Links ]

BANK NEGARA MALAYSIA. 2006. Small and medium enterprise (SME). Annual Report 2005. Available at: http://www.bnm.gov.my [accessed 2009-05-05]. [ Links ]

BECK, T. & DEMIRGUC-KUNT, A. 2006. Small and medium- size enterprises. Access to finance as growth constraint. Journal of Banking and Finance, 30:2931-43. [ Links ]

BECK, T. 2007. Financing constraints of SMEs in developing countries: evidence, determinants and solutions. Available at: http://center.uvt.nl/staff/beck/publications/obstacles/financingconstraints [accessed 2009-05-06]. [ Links ]

BERGER, A.N. &. UDELL, G.F. 1998. The economics of small business finance: the roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle. Journal of Banking & Finance, 22:613-673. [ Links ]

BERGER, A.N. & UDELL, G.F. 2002. Small business credit availability and relationship lending: The importance of bank organizational structure. Economic Journal, 112:F32-F53. [ Links ]

BERGER, A.N. &. UDELL, G.F. 2006. A more complete conceptual framework for SME finance. Journal of Banking and Finance, 30:2945-66. [ Links ]

CLAESSENS, S. 2006. Access to financial services: a review of the issues and public policy objectives. World Bank Research Observer, 21(2):207-40, Fall. [ Links ]

COLE, R.A., GOLDBERG, L.G. & WHITE, L.J. 2004. Cookie cutter vs. character: The micro structure of small business lending by large and small banks. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 39(2):227-51. [ Links ]

DIAMOND, D.W. & DYBVIG, P.H. 1983. Bank runs, deposit insurance and liquidity. The Journal of Political Economy, 91(3):401-419. [ Links ]

GALE, W.G. 1989. Collateral, rationing and government intervention in credit markets. UCLA Economics Working Papers 554. [ Links ]

HIROFUMI, UCHIDA, NOBUYOSHI, YAMORI & UDELL, G.F. 2006. SME financing and the choice of lending technology. RIETI Discussion Paper Series 06-E-025. [ Links ]

ISMAIL, A.B.WAHAB & SITI ZAHRAHBUYONG. 2008. Financing technology-based SMEs in Malaysia: practices and problems. Paper presented at 5th SMEs in Global Economy Conference 2008 SMEs in Global Economy Series: SMEs and Industrial Development in Asian Countries, Organised by Senshu University, Kandajimbocho, Tokyo Japan 2-3 August 2008. Available at: http://senshu.asia.sme.googlepages.com/4Ismail.pdf [accessed 2009-06-10]. [ Links ]

MALAYSIA BANKING AND FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS ACT. 1989. Section 60 & 61. Malaysia. [ Links ]

MALAYSIA. 2006. Census of establishment and enterprise, 2005. Department of Statistics Malaysia. [ Links ]

MURDUCH, J. 1999. The microfinance promise. Journal of Economic Literature, 37(4):1569-1614. [ Links ]

NATIONAL SME DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL 2011. SME annual report, 2009/2010. Malaysia. [ Links ]

NDUBISI, NELSON & SALEH, ALI, SALMAN 2006. SMEs in Malaysia: Development issues. In Small and medium enterprises (SMEs): Malaysian and global perspectives. Pearson/Prentice Hall, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. ISBN 9789833655649. [ Links ]

OECD. 2007. SME financing gap: theory and practices. Vol. 1, Paris: OECD. [ Links ]

OECD. 2007. SME financing gap: theory and practices. Vol. 2, Paris: OECD. [ Links ]

OMAR, M. 2006. Enhancing access to financing by small & medium enterprises in Malaysia. Proceedings of The 2nd International Conference on Financial Systems: Competitiveness of the Financial Sector. Tokyo 1-9. [ Links ]

PETERSEN, M. & RAJAN, R. 1994. The benefits of lending relationship: Evidence from small business data. The Journal of Finance, 1(March):3-37. [ Links ]

SHAMSHUBARIDAH, R. 2005. Loan disbursement status among SMEs in SME Bank Bhd., Report Submitted to SME Bank Bhd. (Unpublished). [ Links ]

SHAMSHUBARIDAH, R. & BERMA, M. 2006. Specialized financial institution: a quencher to the thirst of SMES' financial needs. Proceedings of the Malaysian research group international Conference. Organized by Malaysian Research Group and University of Salford, England. 16-19 Jun.:17-23. [ Links ]

SHAMSHUBARIDAH, R. & BERMA, M. 2008. To give or not to give: dilemma of a specialized financial institution for small and medium enterprises borrowers in Malaysia? Advances in Entrepreneurship Research. C. Veloutsou (ed.) Published by Atiner:423-433. [ Links ]

SHAMSHUBARIDAH, R. & BERMA, M. 2009. Excess and access: issues in the financing of SME in Malaysia. 9th International Conference Financial Management: Financing of Small and medium -sized Enterprises. Measurement and evaluation of Performance. D. Zarzecki (ed.) Published by University of Szczecin:230-242. [ Links ]

SHAMSHUBARIDAH, R. & BERMA, M. 2009. Beyond finance: rectifying growth financing constraints in Malaysian SMEs. Business valuation and value-based management. Dariusz Zarzecki (ed.) Published by University of Szczecin:230-242. [ Links ]

SMIDEC. 2002. SMI development plan (2001-2005), Percetakan Nasional Malaysia Berhad, Kuala Lumpur. [ Links ]

SMIDEC. 2007. SME performance 2007 report. Kula Lumpur, Malaysia (Unpublished). [ Links ]

STIGLITZ, J. & WEISS, A. 1981. Credit rationing in markets with imperfect information, American Economic Review, 71(3):393-410. [ Links ]

WATTANAPRUTTIPAISAN, T. 2003. Four proposals for improved financing of SME development in ASEAN; in: Asian Development Review, 20(2):66-104. [ Links ]

* Corresponding author contact: Shamshubaridah Ramlee, sham5806@gmail.com