Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Lexikos

On-line version ISSN 2224-0039Print version ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.32 Stellenbosch 2022

https://doi.org/10.5788/32-1-1721

ARTICLES

After the Digital Revolution: Dictionary Preferences of English Majors at a European University

Na die digitale revolusie: Woordeboekvoorkeure van studente met Engels as hoofvak aan 'n Europese universiteit

Bartosz Ptasznik

University of Warmia and Mazury, Olsztyn, Poland (bartosz.ptasznik@uwm.edu.pl)

ABSTRACT

The present contribution reports on a recent survey of dictionary-consulting habits and preferences of university students majoring in English at a European university. Amongst the information sought is the choice between digital online dictionaries and traditional print dictionaries, as well as a number of other issues of interest to lexicographers and educators. It was found that online dictionaries have all but replaced the traditional paper dictionary, suggesting that the digital revolution in lexicography hailed by Lew and De Schryver (2014) is complete. A positive finding is that students prefer dictionaries that are highly rated by experts. The paper concludes with a number of pedagogical suggestions.

Keywords: english, lexical information, lexicography, dictionary use, digital literacy, online dictionary

OPSOMMING

In hierdie bydrae word verslag gelewer oor 'n onlangse opname van woordeboekraadplegingsgewoontes en -voorkeure van universiteitstudente met Engels as hoofvak aan 'n Eurpese universiteit. Inligting wat o.a. ondersoek is, is die keuse tussen digitale aanlyn woordeboeke en tradisioneel gedrukte woorde-boeke, asook 'n aantal ander kwessies van belang vir leksikograwe en opvoeders. Daar is bevind dat aanlyn woordeboeke byna die tradisionele papierwoordeboek vervang het, wat daarop dui dat die digitale revolusie in die leksikografie, soos voorspel deur Lew en De Schryver (2014), voltooi is. 'n Positiewe bevinding wat gemaak is, dui daarop dat studente woordeboeke verkies wat hoog aange-skrewe word deur kundiges. Hierdie artikel word afgesluit met 'n aantal pedagogiese voorstelle.

Sleutelwoorde: engels, leksikale inligting, leksikografie, woordeboek-gebruik, digitale geletterdheid, aanlyn woordeboek

1. Introduction

The study of dictionary use is a continuously evolving area of research driven by ongoing advances in methodology as well as technology. A variety of research techniques have been employed in the field of dictionary use over the past years, such as participant and non-participant observations, self-accounts, think-aloud protocols, or videotaping, to mention only a few (Welker 2013; Lew 2015; Schierholz 2015). Also, test-based and experimental research has played a major role in the context of dictionary use by contributing to higher objectivity and reliability of the collected data (Nesi 2000), aided by refinements in statistical inference. A notable development was the pioneering of eye-tracking technology in the study of dictionary consultation behavior (Simonsen 2009, 2011; Tono 2011; Lew et al. 2013, 2018), as was the study of dictionary log-files (De Schryver et al. 2019). Notwithstanding the importance of all the aforementioned methodological approaches, survey-based research remains valid when it comes to gauging user habits, preferences, and attitudes (Kosem et al. 2019). To attain the principal research objectives, this is the technique adopted for the present study which deals with the dictionary preferences of English majors at a European university.

2. Benefits and drawbacks of questionnaires

The questionnaire is a powerful instrument in the sense that survey-based research facilitates the collection of substantial data within a reasonable timeframe. However, there are concerns about the extent to which this approach yields accurate and reliable data. For example, the fact that some respondents could be unwilling to provide honest answers in the questionnaire should be taken seriously (Humblé 2001: 44). Sudman and Bradburn (1982) identify this problem by arriving at the conclusion that either under-reporting or over-reporting can occur when respondents are asked to give detailed information with regards to sensitive issues (family life, private life, income, etc.). As a result, valuable information is withheld from the researcher, which hinders the process of accurate data collection. Another potential problem is specifically related to the responses provided by the respondents. In particular, Hatherall (1984: 184) speculates that some respondents can unintentionally supply researchers with inaccurate data, by posing the much-quoted question: "Are subjects saying here what they do, or what they think they do, or what they think they ought to do, or indeed a mixture of all three"? Given the fact that numerous surveys are presently administered online, there is no denying that in various cases it would be difficult for the researcher to get in touch with the respondents to obtain any additional information necessary for reasons of clarification, unless of course such question items are included in the questionnaire from the outset. Tono (2001: 67) shares Hatherall's point of view by acknowledging that in surveys "the findings are still "indirect" in the sense that they only record what the users think happens, as opposed to what actually happens". Interestingly, Harris (2014: 2-3) expresses his opinion by contending that "[w]riting questionnaires is arguably one of the most challenging forms of writing. It is, in a sense, a conversation between you and hundreds, if not thousands, of diverse respondents. The conversation may take fifteen, thirty, or even forty-five minutes". Last but not least, as Debois (2019) points out, among other problematic issues with questionnaires are: skipped questions, problems related to the interpretation of specific questions by the respondents, the inability of the researcher to analyze the respondents' emotional state of mind, problems with interpreting open-ended1 question responses, respondent bias, lack of personalization, unconscientious answers, questionnaire fatigue.

The reason for which the researcher sets out to prepare a questionnaire is obviously not because this research instrument has its shortcomings in survey-based research. The questionnaire is a tool which allows the researcher to conduct a survey. According to Brown's (2001: 6) definition, questionnaires are "written instruments that present respondents with a series of questions or statements to which they are to react either by writing out their answers or selecting them among existing answers". In other words, a questionnaire constitutes a set of questions prepared by the researcher, whereas a survey is a broader term which could simply be defined as the process of data collection and analysis of the responses provided by the respondents, through the use of research instruments such as the interview or questionnaire. Yet another definition of a survey would be that it is simply "a system for collecting information" (Sue and Ritter 2012: 3). There are countless benefits to drawing up questionnaires, or conducting survey-based research. Debois (2019) lists the following advantages of questionnaires: inexpensive, practical, fast results, scalability, comparability, easy analysis, validity and reliability, standardized, no pressure, respondent anonymity. Mackey and Gass (2005: 94-96) contend that questionnaires hold a serious advantage over individual interviews as they are more economical and practical. In addition, Mackey and Gass mention flexibility as an added advantage, since "questionnaires can provide both qualitative insights and quantifiable data, and (...) are (...) used in a range of research". Furthermore, Jackson and Furnham (2000: 5), who elaborate on surveys and questionnaires for health professionals and administrators, note that questionnaires allow one to "identify opportunities for growth, change and improvement", a remark that is easily transferable to the dictionary user research context. As far as Internet surveys are concerned, Blair et al. (2014: 57) contend that "[t]he two great advantages of Internet surveys are the low cost and the speed of data collection". Blaxter et al. (2006: 79) point to the fact that surveys "may be repeated in the future or in different settings to allow comparisons to be made". In brief, the advantages of surveys for the researcher are plentiful.

All things considered, questionnaires have their advantages and disadvantages. For the sake of clarity, it is the author's belief that the benefits of survey-based research in dictionary user studies outweigh the drawbacks. Questionnaires are an effective tool which provide researchers with comments and reflections of respondents that can be an invaluable source of information. By way of example, bearing in mind that contemporary dictionaries are designed for their users, it must be admitted that depriving oneself of the mere opportunity to acquire inside knowledge or fresh insights from the target user groups, who regularly use newly updated dictionaries, could be perceived as an irrational decision, even if this would mean obtaining only a minuscule amount of information from the collected data. Furthermore, a questionnaire can espedally prove to be a useful instrument for metalexicographers wishing to enhance their research design or consolidate their findings by supplying additional data. Also, in the author's view, questionnaires can serve as a starting point for the main research by revealing aspects worthy of further study. Last but not least, in the context of dictionary use studies, questionnaires can have a didactic purpose as "[u]niversity leaders [can] use results from surveys of students to revise their undergraduate and graduate education programs" (Dillman et al. 2014: 1), and can influence the didactic approach of teaching students how to use dictionaries, what types of dictionaries to use, etc. Importantly, this will be one of the main aims of the present survey. To sum up, a questionnaire-based survey is justified if it is appropriate to the researcher's aims and objectives, and on condition that the appropriate research design is adopted.

The following sections will elaborate on the present survey and its main findings.

3. Aims of the present survey

The aim of the present survey was threefold. First and foremost, the author set out to analyze how English majors at a European university use dictionaries and what types of dictionaries they consult when searching for pertinent information. In particular, the aim was to see to what extent the digital revolution in lexicography (Lew and De Schryver 2014) has completed its cycle among college-level students with an interest in language.

Second, the survey had a didactic purpose. The aim was to collect and analyze the data provided by the participants, and make inferences about how to rethink the approach to teaching English majors how to use dictionaries, what in dictionaries should students pay special attention to, etc.

Finally, the third aim of the survey was to re-establish the usefulness of survey-based research in dictionary user studies. Given the aims of the present survey, an attempt was made to find answers to the following research questions:

1. What types of dictionaries are used by English majors?

2. How do English majors at a European university use dictionaries?

3. Do the findings of the current survey carry any pedagogical implications for dictionary use by English majors?

4. Method, participants and procedure

To meet the objectives of the survey and given the COVID-19 pandemic and restrictions, as well as the fact that students had been attending online classes at the university (academic year 2020/2021), an online questionnaire was created using Microsoft Forms. Microsoft Forms is part of Office 365 and it is an easy-to-use online survey creator. The questionnaire consisted of 20 questions phrased in Polish, the respondents' native language, and included 17 closed-ended questions and 3 open-ended questions which required lengthier responses (see Appendix B). The aim of presenting the questionnaire in the respondents' first language was to ensure the students' best possible comprehension of the survey questions. A mixed question format (i.e., open-ended along closed-ended items) was deemed as the most appropriate in the present context as the aim was not only to collect information that could be expressed numerically (quantitative analysis) but also to obtain information about the attitudes or habits (qualitative analysis) of the students. As far as the multiple-choice questions are concerned (Cohen et al. 2007: 323), the respondents were asked to select either only one answer (a single answer mode), or the students were asked to select more than one answer (multiple answer mode). One dichotomous question (answer options: yes, no) was also included in the survey. A Likert-type rating scale was adopted for selected questions. Using technical language in the questionnaire was avoided, which might have caused confusion (see Lew 2002, 2004). The questionnaire was distributed to the students via Microsoft Teams and e-mail. In order to fill out the questionnaire, the students had to log into their student accounts and complete the questionnaire via Microsoft Forms. A maximum of twenty minutes was allowed for the completion of the task, taking into consideration the fact that surveys should be kept sufficiently short. In this way it was possible to ensure that the participants would give the task their full attention when completing the questionnaire. Published research (e.g. Macer and Wilson 2013, as cited in Brace 2018: 49-50) suggests that the optimum duration of online surveys should be approximately 15 minutes. Given the format of the present survey (inclusion of both closed-ended and open-ended questions), an additional 5 minutes was given to the respondents.

To reiterate, the aim of the present survey was to analyze how English majors at a European university used dictionaries, and also to see what types of dictionaries students consulted when dealing with specific tasks (for example, translation tasks). Given the serious disruptions related to the COVID-19 pandemic, the sample was limited to one university (University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, Poland). This sample, however, was reasonably representative of European institutions of higher learning, based on the fact that Poland appeared to be quite a typical country in a recent pan-European survey (Kosem et al. 2019), and the university itself was a mid-sized public university.

The respondents who participated in the survey were males and females between 19 and 25 years old, and they were native speakers of Polish. They were first-year, second-year, third-year, fourth-year, and fifth-year full-time students majoring in English at the Faculty of Humanities. Their English proficiency level ranged from upper-intermediate to advanced (level B2 and C1 by the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages standards). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and related restrictions, as well as the fact that classes had been taught online for the whole academic year (2020/2021), data were collected from the majority of the students, however, not all of the students of English at the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn could participate in the survey: data were gathered from approximately 66.7% of the students (168 students of English, full-time studies). Consequently, taking into account this limitation, the data were not analyzed by the students' year of study and instead the survey data were summarized altogether as a whole, given the fact that the reasons for self-selection might vary with the year of study.

5. Results and findings

The vast majority of the respondents (99%) said that they usually resorted to online dictionaries for the purpose of dictionary consultation, while only 1% of the students admitted to using paper dictionaries. Nowadays this finding is not at all surprising as online dictionaries hold a real advantage over their printed counterpart, such as easy access, faster entry consultation time, up-to-date content or multimedia features, to name just a few. Also, it is more convenient for the average dictionary user to search for pertinent information in dictionaries which are available online, given that dictionary use very frequently occurs when other computer-based activities are performed (see Kosem et al. 2019).

Notwithstanding the obvious differences between the online and paper dictionary formats and the apparent superiority of the former, in the present survey the respondents were also asked to describe the situations in which they would favor a book-form dictionary over an online dictionary (Open-ended question: Explain in what situations you would prefer to use a paper dictionary rather than an online dictionary.). Interestingly, some of the respondents made it clear that they would rather use a paper dictionary when working on their writing assignments (essays, paragraphs, etc.) or during the process of writing longer theses, such as their BA or MA papers. In addition, another student explained that he would rather resort to a paper dictionary during the process of writing which would not involve using a computer. In other words, this finding implies that there are students who use online dictionaries for computer-based tasks, whereas those students who focus solely on paper-based tasks resort to print dictionaries. Also, it appears that there is a minority of students who believe that paper dictionaries have more reliable content than their counter-part. A few students reported that in situations of doubt they would rather reach for a print dictionary. Further, there were students who said that they would rather use a paper dictionary if they had more time, or when they study or learn for pleasure. A few students reported that paper dictionaries enhanced their ability to memorize words better. Two students said that they consulted book-form dictionaries only when the information that they were looking for in an online dictionary could not be found. Last but not least, one student claimed that he used print dictionaries when giving private lessons.

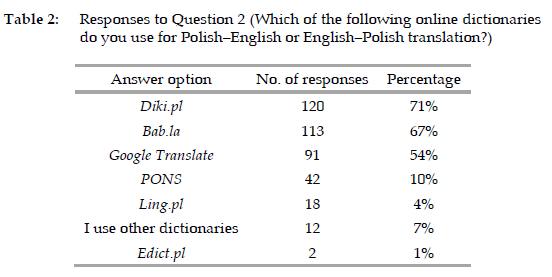

As for the specific online dictionaries that the respondents consult regularly when dealing with Polish-English or English-Polish translation tasks, the majority of the respondents (71%) chose Diki.pl, 67% of the respondents opted for Bab.la, whereas 54% of the students admitted to the fact that they also tended to rely on Google Translate. For this question, the respondents were allowed to select more than one answer. PONS, Ling.pl and Edict.pl turned out to be the students' least favorite dictionaries, achieving scores of 10%, 4% and 1% respectively. Interestingly, 7% of the respondents said that they used other dictionaries or parallel corpus query tools (for example, Reverso Context, Linguee.pl or Cambridge Dictionary) when translating words, texts, etc.

Students who are more fluent and proficient in the English language also endeavor to find relevant information in monolingual learners' dictionaries when dealing with a specific task. Such dictionaries are rich in, for example, collocational information, example sentences, etc. Hence, in the following question the respondents were asked to select the British English monolingual learners' dictionaries that they used (the students were allowed to select more than one option for this particular question). As many as 93% of the students expressed their satisfaction with the Cambridge Dictionary, while the Macmillan Dictionary was rated by the students as the second most frequently used mono-lingual learner's dictionary (59%). Interestingly, less than half of the students admitted to using either the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary (43%), Collins Online Dictionary (22%) or Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (13%), which all appeared to be less useful dictionaries to the participants.

The aim of the following question in the survey was to find out how often students engaged in dictionary consultation. Most respondents declared that they used dictionaries almost every day (40%), 31% of them said that they consulted dictionaries a few times a week, whereas 23% of the students admitted to searching for information in dictionaries every day. 4% of the respondents said they used dictionaries once a week, while 2% admitted to using a dictionary twice a week.

The respondents were also asked how many dictionaries they usually used when looking for the meaning of a difficult word. The main purpose of this question was to see whether students tend to fully engage themselves in the process of dictionary use and refuse to abandon their attempt to find the correct meaning of a word when dealing with more sophisticated items. 18% of the students declared that in such situations they resorted to only one dictionary, 52% admitted to being more inquisitive and as a result using two dictionaries, whereas 30% of the students said that they had a tendency to aid their search for meaning through the use of more than two dictionaries. Using two or more dictionaries for more sophisticated terms seems to be a positive trend, whereas the use of one dictionary should not necessarily be frowned upon provided that students manage to find the correct answer in a single source.

By and large, research has shown that dictionaries play a positive role in writing. For example, Lew (2016) and Tall and Hurman (2002) have demonstrated that dictionaries can significantly improve the quality of writing, whereas other studies (Bishop 2000; East 2008) have indicated that the mere availability of dictionaries in the process of writing brings students psychological reassurance during tests and examinations. In addition, Chon's study (2009) on digital dictionaries showed that Korean students were able to use more sophisticated words in their writing tasks once they had discovered those words when using a dictionary. In light of the importance of the presence of dictionaries in the process of writing, the aim of the present survey was to discover whether English majors tended to use monolingual or bilingual dictionaries when writing essays, letters, reports, etc. The findings reveal that most students used both monolingual and bilingual dictionaries (58%) for writing, 26% of the students used monolingual dictionaries, while only 14% of the students used bilingual dictionaries. 1% of the students said that they did not use dictionaries when producing written texts, whereas 1% of the respondents opted for the other choice. To sum up, deciding to use both monolingual and bilingual dictionaries, or at least having both dictionary types at one's disposal, seems to be the right choice. Nevertheless, it seems worrying that a small proportion of the students either did not resort to using a dictionary, or solely relied on the use of a bilingual dictionary, ignoring the additional benefits that monolingual dictionaries could bring to the process of writing.

Given Question 7, the students were supposed to provide answers regarding the dictionary type they used when searching for the meaning of a newly encountered word. 25% of the students said that they used a monolingual dictionary, 23% admitted to using a bilingual dictionary, whereas 52% declared that they used both a monolingual and bilingual dictionary.

One question that has become relevant recently is whether dictionary users prefer to engage in dictionary consultation by accessing their desktop/laptop computers, smartphones or tablets, and importantly what the reasons are behind these choices. Interestingly, this question has already been partially answered in a recent survey completed by roughly 10,000 dictionary users and non-users (Kosem et al. 2019). The survey revealed that the participants clearly favored computer-based dictionaries over either smartphone-based dictionaries or dictionaries accessed from a tablet. The authors attributed this to the smaller display size of smartphones and the fact that it might be more convenient for dictionary users to access dictionaries from computers, given that most of their activities are computer-based and it seems reasonable to use the same device. It could be added that perhaps not all dictionary users own tablets and hence the sporadic use of dictionaries accessed from tablets. Likewise, in the present survey, the vast majority of the students (74%) declared that they preferred to use computer-based dictionaries (either desktop or laptop computers), 26% preferred using dictionaries from their mobile phones, whereas 1% of the respondents said that they preferred to use dictionaries accessed from a tablet. This finding indicates that computer-based dictionaries are superior to both the smartphone and tablet format of dictionaries, and it seems that the reasons for this preference are once again not coincidental.

To elicit more detailed responses on this particular topic, the participants were asked to elaborate on why they would rather use a dictionary that can be accessed from either a computer (desktop or laptop computer), smartphone or tablet (Open-ended question: Explain why you prefer to use a dictionary which can be accessed either from a computer, smartphone, or tablet.). Some of the typical responses are given below.

I prefer computer-based dictionaries because I spend most of my time in front of a computer.

It is much easier to search for relevant information in dictionaries via a computer. More information can be displayed on a computer screen.

Text from a computer screen is more readable than text from a smaller mobile device.

I always carry a smartphone with me and can use it at any single moment, using smartphone-based dictionaries is simply more convenient.

I usually work using my laptop, it is more convenient for me to access dictionaries from a laptop.

I prefer computer-based dictionaries because I can quickly access information from a few dictionaries by opening multiple tabs in Chrome.

Using computers is simply more convenient.

A laptop allows me to use multiple dictionaries at the same time.

I usually use dictionaries for writing, and I write using Microsoft Word, so it is more convenient to use computer-based dictionaries.

Display size is important, a larger display size is better for my eyesight.

When I encounter an unknown word, I can use my mobile phone and quickly find the word's meaning.

I prefer smartphones to computers, so I use smartphone-based dictionaries. Smart-phones are my favorite device.

Whenever classes are taught online (due to COVID-19) I always use my computer, so I prefer to access dictionaries from a computer.

I can type faster using a computer keyboard.

A smartphone allows me to check a word's meaning regardless of where I am. I prefer smartphone-based dictionaries because I am not always at home and my laptop is turned off.

I don't use my smartphone too often, so I prefer to access dictionaries from a computer.

The advertisements in smartphones are annoying, they take up too much space on my smartphone screen, I prefer computer-based dictionaries.

I always use my laptop, there is no point in using two different devices at the same time.

I do not have a tablet.

Having two different devices (laptop and smartphone) at your disposal is more convenient because you can be involved in two different activities at the same time.

I am more accustomed to using a traditional computer keyboard rather than a touch screen.

The text is larger on a computer screen.

Dictionary entries displayed on computer screens present more information. It depends on the situation. I prefer to use smartphone-based dictionaries during my classes. I use computer-based dictionaries at home.

In another question of the survey, the respondents were asked how they normally learned the pronunciation of a word. The participants had the opportunity to select either one or two answers depending on their own personal strategies for pronunciation search. As many as 96% of the students opted for online dictionaries and audio recordings of British and American English native speakers. It must be admitted that the fact that students discover the pronunciation of selected vocabulary items in this manner means that students are well aware of where reliable information about the pronunciation of words can be found, they are skilled at solving problems, and are resourceful enough to find the information they need independently of anyone's help. 27% of the students reported looking for the pronunciation of a word on a random Internet website, 11% would ask a friend for help, 10% would ask their teachers, while only 7% of the students said that they would use a paper dictionary for phonetic transcription. 11% of the survey participants admitted to employing other strategies when searching for a word's pronunciation.

To analyze the students' decision-making when encountering an unknown word, the respondents were asked what it is that they specifically do when faced with such a situation. The following responses were elicited: 59% of the students claimed that they used a dictionary, 20% said that they browsed the Internet for information, 19% said that they tried to guess the word's meaning from context, 1% said that they asked someone what the word means, 1% said that they simply ignored the word, and 1% of the students chose the none of the above option. The students were asked to select only one answer, which means that it is thought-provoking why as many as 41% of the students replied that they would not engage in dictionary consultation. On the one hand, it seems obvious that some students may already have some general idea about what the word means and so they resort to the Internet, or they simply decide to guess a word's meaning from context in order to receive confirmation of the meaning of the item in question. Nowadays browsing the Internet for information is nothing out of the ordinary, which partially explains why 20% of the students chose this option. On the other hand, students of English are expected to find reliable information about a word so that they not only know what it means, but that they also manage to learn more about this word's grammatical or collocational environment. This is where dictionaries should come into play, given that the main function of dictionaries is explaining word meanings. In other words, more proficient students should endeavor to discover how to use a word in the language. Hence, it seems reasonable to assume that in such situations students should not only rely on intuition and common sense, but they ought to strictly adhere to common practices which in this specific scenario clearly involve the need for dictionary consultation. Even if such a student intends to only obtain information about what the word means, regardless of acquiring information about how this word is used in the language, dictionaries still seem to be the most logical solution in the context of a student of English.

To see how important illustrations are to dictionary users, the respondents in the current survey were asked whether they thought that the presence of illustrations in dictionaries was beneficial to the dictionary user. Significantly, Lew et al. (2018) focused in their eye-tracking study on pictorial illustrations in English mono-lingual learners' dictionaries and their effect on dictionary users' attention, as well as extraction and retention of meaning. In other words, it could be said that the researchers sought to assess the usefulness of the presence of illustrations in monolingual dictionary entries for learners of English. In the present survey, the respondents were simply asked what their opinions were on the inclusion of illustrations in dictionary entries. 33% of the respondents said that illustrations were probably useful, 16% said that they were useful, 19% said that they were probably not useful, 8% were of the opinion that they were not needed in dictionaries. 24% of the students said that it was difficult to say. Taking these percentages into account, it appears that more than half of the students (51%) thought that illustrations were either not needed in dictionary entries or the students were simply undecided. Put another way, these data illustrate that the students could be divided into two separate groups which represent opposite ends of the spectrum. Roughly 50% of the students rather perceive illustrations as beneficial in dictionary use, whereas the other half are rather doubtful or unconvinced that they are needed.

Example sentences provide dictionary users with additional information about words. For instance, one can derive collocational or grammatical information from examples and learn how a particular word should be used in the language in speech or writing. The author of the present survey attempted to see whether examples2 are beneficial to dictionary users. To be more precise, the participants were asked in the survey to say whether they read example sentences in English monolingual learners' dictionaries. 74% of the students admitted to the fact that they usually consulted examples in dictionaries, 21% said that they sometimes read them, 5% said that they usually did not even browse through them, whereas 1% of the students said that it was difficult to say whether they read examples in dictionaries or not. Assuming that the students are reporting here what they are actually doing during dictionary consultation, it must be contended that the data are promising, and that the students recognize the importance of reading example sentences in monolingual dictionaries for learners of English.

In the following question the respondents had to say whether they thought that dictionary users could find frequency information about words in an English monolingual learner's dictionary. 117 of the respondents (70%) answered yes, while 51 of the respondents (30%) were of the opinion that it was not possible to find such information in a dictionary. This finding suggests that there are still learners of English (51 students, 30% of the survey participants) who need to be made more aware of what type of information English monolingual learners' dictionaries have to offer to the average dictionary user.

Given that monolingual dictionaries for learners of English are a source of grammatical information for dictionary users, the author of the survey attempted to analyze the frequency of dictionary use for getting information about grammar from dictionaries. 25% of the students claimed that they often tried to obtain grammatical information from English monolingual learners' dictionaries, while 7% declared that they tried to acquire this information very often. This finding suggests that 32% of the students were rather keen to learn more about grammar from dictionaries and endeavored to get such information regularly. On the contrary to this finding, there were students who either rarely (16%) or very rarely (10%) tried to acquire grammatical information from dictionaries, or there were students who even did not search for this type of information (I do not look for grammatical information in dictionaries - 5%). These data indicate that 30% of the students infrequently engage in dictionary use for the purpose of extending their grammar knowledge. One reason behind this statistic could be that dictionary users are not interested in obtaining this type of information from dictionaries. Another possibility is that they prefer to use grammar books and do not perceive dictionaries as a potential source of grammatical information. 38% of the students admitted to the fact that they sometimes decided to try to learn grammar from a monolingual dictionary for learners of English. To sum up, more or less a third of the students use dictionaries regularly with the aim of also obtaining grammatical information, roughly a third of the students occasionally use dictionaries for the very same purpose, whereas approximately a third of the students seldom use dictionaries to get information about grammar, or they do not use dictionaries for this purpose.

An additional question attempted to check how frequently dictionary users consulted either the front or back matter of their print dictionaries. Not a single respondent admitted to using a dictionary for the purpose of obtaining information from the front or back matter frequently (answer option - often). 6% of the respondents admitted to using dictionaries in order to get information from either the front or back matter of their dictionaries sometimes, 24% declared that they engaged in such dictionary consultation rarely, whereas 70% of the students did not read or even browse through their dictionaries for such information.

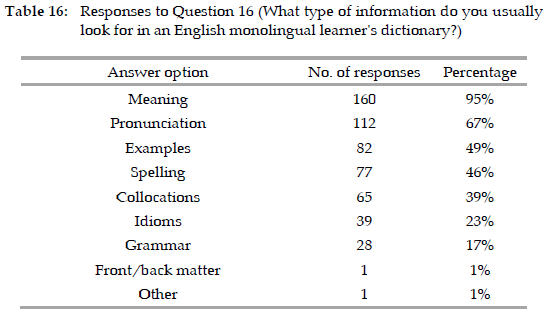

As for the type of information that students usually search for in a monolingual dictionary for learners of English, the main finding of the current survey is that students primarily consult dictionaries for meaning. In the present survey, 95% of the students selected this answer (the students were allowed to select more than one answer for this question). Furthermore, it appears that the second reason for which dictionary users reach for a monolingual dictionary is to acquire pronunciation information (67%), and what is interesting is that this specific type of information in dictionaries plays a more important role for dictionary users than the presence of examples (49%), information about spelling (46%), collocations (39%), or idioms (23%) in a dictionary. Pessimistically, acquiring grammatical information from dictionaries is even less important for the students (17%), not to mention the information that can be obtained from either the front or back matter of a print dictionary.

A recent empirical study by Dziemianko (2020) explored the relation between online advertisements and language reception, production and learning. Interestingly, another aim was to analyze what dictionary users had thought about being exposed to online dictionary entries appearing with advertisements. In the current survey, the respondents were asked to give their opinion on the presence of advertisements in online dictionary entries. 45% of the respondents were of the opinion that such advertisements in online dictionary entries were disturbing, 39% reported that they were not annoyed by the presence of advertisements, whereas 16% of the students chose the difficult to say answer. In general, the conclusion that can be drawn from the survey is that the opinions of the students vary and that one possible factor which comes into play in the present context is one of individual preferences of the students.

In the third open-ended question (Is there anything you do not like in dictionaries? Is anything missing from dictionaries?), the respondents had the opportunity to express their opinions regarding the lexicographic content of dictionaries. Most responses were positive, as the majority of students expressed their general satisfaction with dictionaries. However, roughly 10% of the students complained that they did not always manage to find the information they were looking for in an English monolingual learner's dictionary, and attributed this to an insufficient amount of information in dictionaries about how a particular word can be used in different contexts. This problem in their view could be resolved by making more example sentences available to users in online dictionaries. Additionally, a handful of respondents accentuated the need for the incorporation of more example sentences in monolingual learners' dictionaries for collocations.

6. Discussion and conclusions

The results indicate that, when it comes to bilingual dictionaries, English majors favor Diki.pl, Bab.la and Google Translate over the remaining online dictionaries, when dealing with either Polish-English or English-Polish translation tasks. The 'other dictionary' option (beyond one of: Diki.pl, Bab.la, Google Translate, PONS, Ling.pl, Edict.pl) was only supplied by 7% of the participants. The most frequent additions here were: Reverso Context, Linguee.pl, and Cambridge Dictionary. Cambridge Dictionary was also the students' dictionary of choice as a monolingual learner's dictionary (93%). It is, however, possible that the students chose this dictionary as their favorite monolingual dictionary not only because the dictionary gives the students access to the Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary, but because the portal also includes bilingual dictionaries (such as the Cambridge English-Polish Dictionary and Cambridge Polish-English Dictionary) selectable from a drop-down list. In other words, this online resource guarantees students exposure to the target language alone and at the same time creates the opportunity for students to engage in either Polish-English or English-Polish translation, which appears to be an added advantage to the monolingual learner's dictionary. The Macmillan Dictionary was rated by the students as their second favorite monolingual dictionary (59%), whereas the remaining three monolingual learners' dictionaries (Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary, Collins Online Dictionary, Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English) were all selected by less than 50% of the students.

The data obtained from the current survey confirm earlier findings from Lew and Szarowska's study (2017), in which a systematic evaluation framework for online bilingual dictionaries was proposed and applied to the English-Polish language pair. That study found that Diki.pl was the most frequently used and highest-ranked extant dictionary. In the present survey, Diki.pl also turned out to be the most-frequently consulted dictionary, and it is reassuring that this high popularity corresponds with the outcome of Lew and Szarowska's expert quality evaluation: it appears that the users know what they are doing when they elect to use a specific dictionary and are able to appreciate the quality.

It is by no means surprising that the overwhelming majority of the students resort to the use of online dictionaries, given the benefits of this specific dictionary format. Also, this finding is line with the study of Kosem et al. (2019: 109) in which it was found that the younger participants clearly favored the digital format of dictionaries over the paper format. It suggests that the digital revolution (hailed by Lew and De Schryver 2014) has all but completed its course. However, the collected evidence points to the fact that print dictionaries cannot yet be brushed aside by lexicographers, as there are students who use the bookform dictionary, for example, for their writing assignments (essays, BA and MA theses) or when the students focus on paper-based tasks. Another reason for the use of a paper dictionary is to simply enhance the learning process, as some students reported that they believed the use of a paper dictionary to be an effective memorization technique. Whether this is true or not would need to be empirically tested; however, studies (Bishop 2000; East 2008) have demonstrated that the availability of dictionaries in the process of writing during examinations and tests brings students psychological reassurance and alleviates stress. By the same token, it is possible that given individual preferences of students and their habits of using print dictionaries rather than online dictionaries for specific tasks, the mere use of a paper-form dictionary could result in some sort of psychological support to such dictionary users, which in turn could perhaps lead to better memorization of words. In general, the use of a paper dictionary requires more time and effort, and so perhaps the fact that one devotes more attention to dictionary consultation via the paper medium can contribute to enhanced memorization of vocabulary.

The findings suggest that most English majors use dictionaries on a regular basis: 63% of the students reported that they consulted dictionaries (nearly) every day, while 31% of the students declared that they engaged in dictionary use a few times a week. What needs to be stressed in the present context is that it seems reasonable to assume that the frequency of dictionary consultation must be related to students' individual preferences and hence it would be unwise to say that learners of English should engage in dictionary consultation on a daily basis. Some students simply have to use dictionaries more often than other students given their heavy workload. As long as students manage to bring back the right meaning when deciding to use a dictionary, and provided that students use a dictionary when the task at hand requires them to use one, it seems that a less sporadic use of dictionaries should not be frowned upon. When it comes to looking up more sophisticated words in the dictionary, the majority of the survey participants tend to use at least two dictionaries for consultation, which seems to be a positive trend. Nevertheless, using one dictionary can also be perceived as an optimal strategy on the condition that dictionary users find what they are looking for in a single source.

The findings show that the average dictionary user prefers to access dictionaries from a desktop or laptop computer as opposed to either a smartphone device or tablet. This finding appears to be transferable to the larger context of European dictionary users as these observations are in agreement with those of Kosem et al. (2019), who found that their participants (roughly 10,000 respondents from nearly thirty countries) clearly favored computer-based dictionaries over smartphone-based dictionaries.

In addition, upper-intermediate and advanced-level dictionary users have a tendency to search for pronunciation information in online dictionaries, which seems to be the most reasonable choice. This should not come as a surprise as audio recordings of native speakers in digital dictionaries are easily accessible online and they provide users of the language with quick and easy answers as to how a word should be properly pronounced in the target language.

More than two fifths of the participants in the survey admitted to either browsing the Internet for information or guessing a word's meaning from context when encountering an unknown word in English, rather than using a dictionary. On the one hand, this finding is rather surprising given that English majors participated in the survey. However, taking into account the fact that the sample included 19-25-year-olds, who can safely be called digital natives growing up in a society of digital technologies, it becomes more clear why dictionary users tend to resort to simpler strategies when encountering unknown words.

The majority of the participants seemed to recognize the importance of example sentences in dictionaries. In their open-ended feedback, the students strongly emphasized their need for even more examples in dictionaries, notwithstanding the numerous examples that are already available, for instance, in the current English monolingual learners' dictionaries. Given that storage space in the context of online dictionaries is no longer a problem for the lexicographer, perhaps it would be possible to at least rethink the approach of dictionary-making in the context of online dictionaries, regarding the inclusion of the most optimal number of example sentences in dictionary entries. Studies conducted by Frankenberg-Garcia (2012, 2014, 2015) are a promising start.

Finally, I would like to make a comment with regards to the third research question posed in the survey (Research question 3: Do the findings of the current survey carry any pedagogical implications for dictionary use by English majors?). 30% of the participants reported that they thought that English monolingual learners' dictionaries did not provide dictionary users with frequency information, which in turn means that 70% of the participants were aware that frequency information was available. Still, a third of the participants were apparently misinformed or simply had never been taught by their teachers that this type of information could be obtained from a monolingual pedagogical dictionary for learners of English. The aim of including frequency information in such a dictionary is, for example, to teach learners which words are frequently used in the language and, consequently, which specific words students should learn to be able to communicate in the target language fluently. This

salient feature of monolingual learners' dictionaries also allows one to distinguish between words and expressions which are frequently used in either spoken or written English. To sum up, in the author's view, teaching English majors that frequency information is available in monolingual learners' dictionaries should be made a priority in schools and dictionary classes held at universities. Likewise, I would like to make a further comment in relation to grammatical information which is incorporated into dictionary entries. Roughly two thirds of the survey participants admitted to consulting dictionaries for grammar rather occasionally, rarely, or very rarely. It is true that, in general, dictionaries are not perceived as the primary source of grammatical information for students. However, it is the author's belief that the importance of the mere possibility of acquiring syntactic information from monolingual learners' dictionaries should at least be stressed by English teachers and lecturers of English departments at universities, as modern dictionaries are much more than just books or digital products consisting of word lists and their meanings. In the author's view, dictionaries constitute repositories of knowledge, or are simply reference sources packed with information about word meanings, grammar, collocations, and other types of information.

Acknowledgements

I thank Prof. Robert Lew for valuable suggestions, constructive comments and discussions.

Endnotes

1 Open-ended question responses generally require more time and hence respondents can also be reluctant to elaborate on their answers, let alone provide responses for such question items. For more information on open-ended questions in survey-based research see Muijs (2004).

2 To learn more about empirical research dealing with the usefulness of examples in dictionary use, see Frankenberg-Garcia's studies (2012, 2014, 2015) in which an elaborate research design was adopted.

References

Bishop, G. 2000. Dictionaries, Examinations and Stress. Language Learning Journal 21: 57-65. [ Links ]

Blair, J., R.F. Czaja and E.A. Blair. 2014. Designing Surveys: A Guide to Decisions and Procedures. Third edition. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Blaxter, L., C. Hughes and M. Tight. 2006. How to Research. Third edition. Maidenhead: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Brace, I. 2018. Questionnaire Design: How to Plan, Structure and Write Survey Material for Effective Market Research. Fourth edition. London: Kogan Page. [ Links ]

Brown, J.D. 2001. Using Surveys in Language Programs. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Chon, Y.V. 2009. The Electronic Dictionary for Writing: A Solution or a Problem? International Journal of Lexicography 22(1): 23-54. [ Links ]

Cohen, L., L. Manion and K. Morrison. 2007. Research Methods in Education. Sixth edition. London/ New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Debois, S. 2019. 10 Advantages and Disadvantages of Questionnaires. https://surveyanyplace.com/blog/questionnaire-pros-and-cons/. Accessed 22 July, 2021.

De Schryver, G.-M., S. Wolfer and R. Lew. 2019. The Relationship between Dictionary Look-up Frequency and Corpus Frequency Revisited: A Log-file Analysis of a Decade of User Interaction with a Swahili-English Dictionary. GEMA Online Journal of Language Studies. 19(4): 1-27. [ Links ]

Dillman, D.A., J.D. Smyth and L.M. Christian. 2014. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. [ Links ]

Dziemianko, A. 2020. Smart Advertising and Online Dictionary Usefulness. International Journal of Lexicography 33(4): 377-403. [ Links ]

East, M. 2008. Dictionary Use in Foreign Language Writing Exams: Impact and Implications. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Frankenberg-Garcia, A. 2012. Learners' Use of Corpus Examples. International Journal of Lexicography 25(3): 273-296. [ Links ]

Frankenberg-Garcia, A. 2014. The Use of Corpus Examples for Language Comprehension and Production. ReCALL 26(2): 128-146. [ Links ]

Frankenberg-Garcia, A. 2015. Dictionaries and Encoding Examples to Support Language Production. International Journal of Lexicography 28(4): 490-512. [ Links ]

Harris, D.F. 2014. The Complete Guide to Writing Questionnaires: How to Get Better Information for Better Decisions. Durham, North Carolina: I&M Press. [ Links ]

Hatherali, G. 1984. Studying Dictionary Use: Some Findings and Proposals. Hartmann, R.R.K. (Ed.). 1984. LEXeter '83 Proceedings: Papers from the International Conference on Lexicography at Exeter, 9-12 September 1983: 183-189. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Humble, P. 2001. Dictionaries and Language Learners. Frankfurt am Main: Haag und Herchen. [ Links ]

Jackson, C.J. and A. Furnham. 2000. Designing and Analysing Questionnaires and Surveys. A Manual for Health Professionals and Administrators. London: Whurr Publishers. [ Links ]

Kosem, I., R. Lew, C. Müller-Spitzer, M.R. Silveira, S. Wolfer, et al. 2019. The Image of the Monolingual Dictionary across Europe. Results of the European Survey of Dictionary Use and Culture. International Journal of Lexicography 32(1): 92-114. [ Links ]

Lew, R. 2002. Questionnaires in Dictionary Use Research: A Reexamination. Braasch, A. and C. Povlsen (Eds.). 2002. Proceedings of the Tenth EURALEX International Congress, EURALEX 2002, Copenhagen, Denmark, August 13-17, 2002, Vol.1: 267-271. Copenhagen: Center for Sprogtek-nologi, Copenhagen University.

Lew, R. 2004. Which Dictionary for Whom? Receptive Use of Bilingual, Monolingual and Semi-Bilingual Dictionaries by Polish Learners of English. Poznan: Motivex. [ Links ]

Lew, R. 2015. Opportunities and Limitations of User Studies. OPAL - Online publizierte Arbeiten zur Linguistik 2(2015): 6-16. https://ids-pub.bsz-bw.de/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/3772/file/Research_into_dictionary_use-2015.pdf. Accessed 10 September 2022. [ Links ]

Lew, R. 2016. Can a Dictionary Help you Write Better? A User Study of an Active Bilingual Dictionary for Polish Learners of English. International Journal of Lexicography 29(3): 353-366. [ Links ]

Lew, R. G.-M. and De Schryver. 2014. Dictionary Users in the Digital Revolution. International Journal of Lexicography 27(4): 341-359. [ Links ]

Lew, R., M. Grzelak and M. Leszkowicz. 2013. How Dictionary Users Choose Senses in Bilingual Dictionary Entries: An Eye-tracking Study. Lexikos 23: 228-254. [ Links ]

Lew, R., R. Kazmierczak, E. Tomczak and M. Leszkowicz. 2018. Competition of Definition and Pictorial Illustration for Dictionary Users' Attention: An Eye-tracking Study. International Journal of Lexicography 31(1): 53-77. [ Links ]

Lew, R. and A. Szarowska. 2017. Evaluating Online Bilingual Dictionaries: The Case of Popular Free English-Polish Dictionaries. ReCALL 29(2): 138-159. [ Links ]

Macer, T. and S. Wilson. 2013. A Report on the Confirmit Market Research Software Survey. https://www.quirks.com/articles/a-report-on-the-confirmit-market-research-software-survey-1. Accessed 23 July, 2021.

Mackey, A. and S.M. Gass. 2005. Second Language Research: Methodology and Design. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Muijs, D. 2004. Doing Quantitative Research in Education with SPSS. London: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Nesi, H. 2000. The Use and Abuse of EFL Dictionaries. How Learners of English as a Foreign Language Read and Interpret Dictionary Entries. Lexicographica Series Maior 98. Tübingen: Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Schierholz, S.J. 2015. Methods in Lexicography and Dictionary Research. Lexikos 25: 323-352. [ Links ]

Simonsen, H.K. 2009. Vertical or Horizontal? That is the Question: An Eye-track Study of Data Presentation in Internet Dictionaries. Paper presented at the Eye-to-It Conference on Translation Processes, Sentence Processing and the Bilingual Mental Lexicon, Business School, Copenhagen, Denmark, April 25-29, 2009.

Simonsen, H.K. 2011. User Consultation Behaviour in Internet Dictionaries: An Eye-tracking Study. Hermes 46: 75-101. [ Links ]

Sudman, S. and N.M. Bradburn. 1982. Asking Questions: A Practical Guide to Questionnaire Design. Jossey-Bass Series in Social and Behavorial Sciences. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Sue, V.M. and L.A. Ritter. 2012. Conducting Online Surveys. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Tall, G. and J. Hurman. 2002. Using Dictionaries in Modern Language GCSE Examinations. Educational Review 54(3): 205-217. [ Links ]

Tono, Y. 2001. Research on Dictionary Use in the Context of Foreign Language Learning. Focus on Reading Comprehension. Lexicographica Series Maior 106. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Tono, Y. 2011. Application of Eye-tracking in EFL Learners' Dictionary Look-up Process Research. International Journal of Lexicography 24(1): 124-153. [ Links ]

Welker, H.A. 2013. Methods in the Research of Dictionary Use. Gouws, R.H., U. Heid, W. Schweickard and H.E. Wiegand (Eds.). 2013. Dictionaries. An International Encyclopedia of Lexicography. Supplementary Volume: Recent Developments with Focus on Electronic and Computational Lexicography: 540-547. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter.