Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Dental Journal

On-line version ISSN 0375-1562Print version ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.80 n.1 Johannesburg Feb. 2025

https://doi.org/10.17159/sadj.v80i01.20071

CASE REPORT

Methotrexate-induced oral mucositis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A case series and literature review

J FourieI; D LaubscherII; T SimelaneIII

IDepartment of Periodontics and Oral Medicine, School of Dentistry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa. ORCID: 0000-0002-8674-8145

IIDepartment of Periodontics and Oral Medicine, School of Dentistry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa. ORCID: 0009-0005-2106-8113

IIIDepartment of Periodontics and Oral Medicine School of Dentistry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Methotrexate is used as both an antineoplastic drug and disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug. In both cases, methotrexate use may result in oral mucositis. Dentists are likely to manage patients with rheumatoid arthritis and should consider this adverse drug event when mouth ulcers are observed.

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES: This study aims to report on five patients with rheumatoid arthritis who presented with methotrexate-induced oral mucositis (MIOM) and to perform a literature review of the condition.

DESIGN/METHODS: The clinical history, oral mucosal features and results of special investigations of five patients who presented to the Oral Medicine Clinic with MIOM were recorded. Upon identification of methotrexate use as the cause of oral ulceration, the patients were managed collaboratively with their respective physicians.

RESULTS: These cases demonstrate that dentists should recognise that chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis may also be seen among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and not necessarily only within the traditional context of cancer treatment. Dentists should consider the possibility of drug reactions and interactions that may result in oral ulcers.

CONCLUSIONS: Dentists play a pivotal role in the diagnosis and treatment of mouth ulcers. Careful history taking and suspicion of adverse drug events described here may facilitate a clinical diagnosis, which can be further supported through special investigations. Collaboration with the treating medical clinician is imperative in the management of a patient who presents with MIOM, as treatment modification is required.

Keywords: Methotrexate, oral ulceration, mucositis, DMARD, pancytopenia, rheumatoid arthritis

Abbreviations

MTX: methotrexate

MIOM: methotrexate-induced oral mucositis

DMARDs: disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs

RA: rheumatoid arthritis

LDMTX: low-dose methotrexate

ADR: adverse drug reaction

UPOHC: University of Pretoria Oral Health Centre

FBC: full blood count

RCC: red cell count

Hb: haemoglobin

MCV: mean corpuscular volume

MCH: mean corpuscular haemoglobin

MCHC: mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration

GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease

eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate

DHFR: dihydrofolate reductase

DHF: dihydrofolate

THF: tetrahydrofolate

TS: thymidylate synthase

AICART: aminoimidazole carboxamide ribonucleotide transformylase

RFC1: reduced folate carrier 1

MTX-PG: methotrexate-polyglutamate

PPI: proton pump inhibitor

INTRODUCTION

Methotrexate (MTX) was originally developed to treat malignant diseases.1 But, it has since become the first choice among the disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA)2-6 because of its anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating properties. When used for the treatment of RA, long-term low-dose MTX (LDMTX) therapy is employed7 which typically does not exceed 25mg per week.5

Despite the emergence of numerous targeted therapies, MTX remains pivotal in RA treatment due to its effectiveness and tolerability,4,6 favourable safety profile and fewer reported toxicities compared to other DMARDs.8 Yet, up to a third of patients may experience treatment failure due to a lack of efficacy, while adverse drug reactions (ADRs) remain the primary reason for MTX discontinuation.8

Oral mucositis is one of the ADRs associated with LDMTX use that may require treatment discontinuation. Here, we report on five cases that presented to the Oral Medicine Clinic of the University of Pretoria's Oral Health Centre in which LDMTX therapy for RA resulted in MTX-induced oral mucositis (MIOM).

Permission was obtained from the University of Pretoria, Faculty of Health Sciences, Research Ethics Committee clearance number 507/2024, following informed consent from the participants.

Case 1

A 78-year-old woman presented with a four-month history of worsening mouth ulcers, leaving her unable to eat. A biopsy three months prior indicated a non-specific ulcer with reactive atypia. She had RA, hypertension, depression and a gastric ulcer, treated with MTX (25mg/week for 20 years), folic acid (5mg), nifedipine, enalapril, pantoprazole and sertraline. A year earlier, she was hospitalised for pancytopenia, with slightly impaired kidney function, unassessed liver function and a serum MTX level of <0.02umol/ml (see Table I).

Subsequent blood tests showed megaloblastic anaemia, increased RDW, impaired kidney function and low serum albumin.

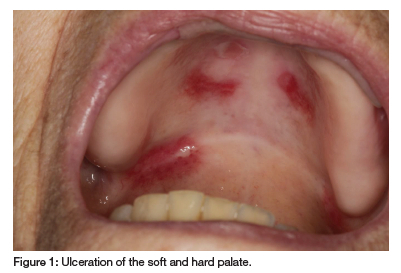

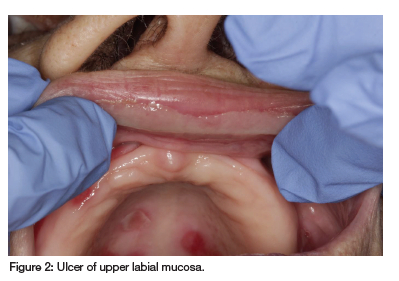

Oral examination revealed erosions and ulcers on the hard and soft palate and labial mucosa, covered by a fibrinopurulent membrane (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). Vesicullobullous diseases, such as mucous membrane pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris, were considered, but MTX's immunosuppressive effects made these conditions less likely. Thus, a diagnosis of MIOM was made. The patient was managed with topical glucocorticosteroids (betamethasone suspension mouthrinse and clobetasol ointment) and her rheumatologist was informed of this ADR. Symptomatic relief was minimal until MTX discontinuation, after which the ulcers healed.

The patient's earlier blood results suggest that reduced e-GFR, possibly exacerbated by concurrent PPI and ACE inhibitor use, led to ineffective MTX clearance. Combined with low albumin levels, this resulted in an effective MTX overdose.

Case 2

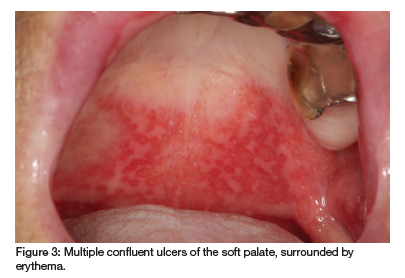

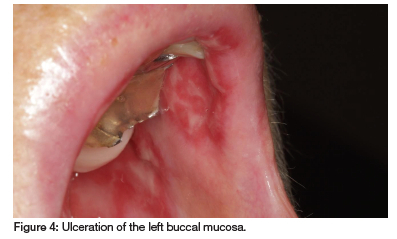

A 69-year-old woman presented with persistent oral ulcers over the past eight months and recent hair loss. Previously diagnosed with recurrent aphthous ulcers or pemphigus vulgaris, she received unsuccessful treatment with antibiotics and antifungals. Suffering from RA with noticeable hand deformities, she takes prednisone (10mg), MTX (20mg/week) and folic acid (5mg). However, she recently began taking MTX daily due to a pharmacy error. Diffuse ulcers and erosions on her soft palate, buccal and labial mucosa, which became confluent and covered by a fibrinopurulent membrane, were observed (see Figures 3 and 4). Returning to weekly MTX dosing led to the healing of the MIOM.

Case 3

A 59-year-old woman was referred by an oral surgeon for a painful oral ulcer on the lower labial mucosa, persisting for three weeks and unresponsive to her usual miconazole treatment for recurrent ulcers. She had a stroke 15 years ago and is being treated for RA, fibromyalgia, depression, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, hypothyroidism and GERD. Her medications include MTX (25mg/week for Ave years), folic acid (5mg), levothyroxine, liothyronine, tiotropium inhaler, buffered Vitamin C, warfarin, Stilpane (paracetamol, promethazine, codeine phosphate), sulphasalazine, celecoxib, pantoprazole, montelukast, salmeterol/ fluticasone, salbutamol, torasemide, bisoprolol, betahistine, aspirin, atorvastatin, Calciferol, levetiracetam, ezetimibe, alprazolam, amitriptyline, pregabalin, ziprasidone, zolpidem, topiramate and loratadine.

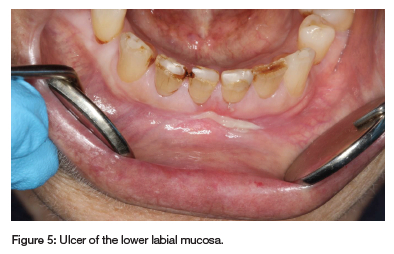

A solitary ulcer, covered by a fibrinopurulent membrane, was observed on the lower labial mucosa (see Figure 5). A biopsy was contraindicated due to her elevated INR of 8, and MIOM was suspected. Drug interactions were likely, given her extensive medication regimen, particularly involving NSAIDs, pantoprazole and levetiracetam. Her rheumatologist stopped MTX treatment, leading to ulcer resolution. An FBC was unremarkable. The patient's recurrent oral ulcers have since diminished, but she was cautioned against using miconazole and warfarin concurrently due to the risk of adverse drug interactions.

Case 4

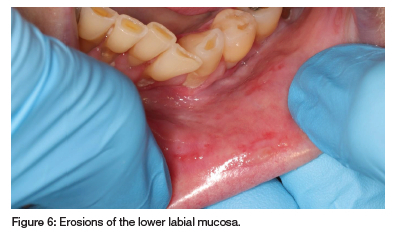

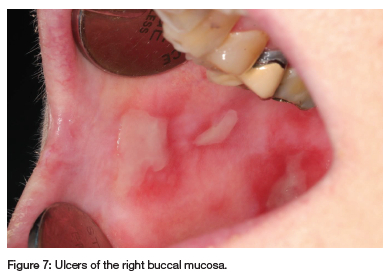

A 66-year-old woman was referred by an oral surgeon for recurrent oral ulcerations that have worsened over the past year and were unsuccessfully treated with glucocorticosteroid and doxycycline mouth rinse. The patient has RA, hypertension, depression, gout, asthma and migraine, and has been taking MTX (20mg/week for 12 years), folic acid (5mg), prednisone (5mg), betahistine, Ultracet (tramadol and paracetamol), ferrous bisglycinate chelate, leflunamide, furosemide, celecoxib, allopurinol, salbutamol inhaler, Theoplus, potassium chloride, desloratadine, salmetrol/fluticasone inhaler, minair, Zolpidem, esomeprazole, domperidone, nifedipine, indapamide, topiramate and eletriptan as needed. Multiple ulcers with irregular borders, covered by a fibrinopurulent membrane and surrounded by erythema, were observed on the buccal and labial mucosa (see Figures 6 and 7). A differential diagnosis of vesiculobullous diseases was considered but deemed unlikely due to her immunosuppressive treatment and lack of response to topical corticosteroids. MIOM was suspected, but a biopsy was performed to rule out other pathologies. Histopathology confirmed the ulcer was non-specific. Recent blood tests showed decreased WCC, increased RDW, gamma-glutamyl transferase, aspartate transferase and normal eGFR and albumin. Increases in liver enzymes are common in long-term LDMTX therapy.9

Drug interactions likely contributed to MTX toxicity, with celecoxib, esomeprazole, indapamide and furosemide displacing MTX from albumin and reducing its renal clearance.

The rheumatologist discontinued the patient's LDMTX, leading to the ulcers healing without complications.

Case 5

An 84-year-old woman was referred by an oral surgeon for the assessment of recurrent oral ulcerations, which have become persistent over the past six months.

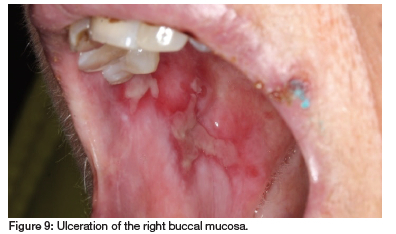

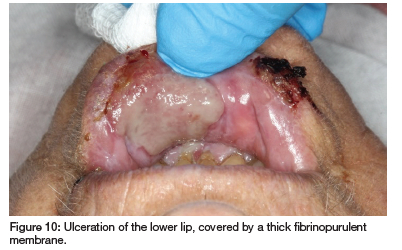

The patient has RA, hypertension, hypothyroidism, insomnia, restless leg syndrome, GERD and had a myocardial infarction and pulmonary embolism two years ago. She takes MTX (10mg/week for 30 years), carvedilol, clopidogrel, quetiapine fumarate, levothyroxine sodium, simvastatin, pramipexole, paracetamol, enalapril, probiflora, pyridoxine (vitamin B6) and pantoprazole. Clinical examination revealed irregular ulcers with fibrinopurulent membranes surrounded by erythema on the buccal and labial mucosa, extending to the lip vermillion and skin (see Figures 8, 9 and 10). As the patient had not supplemented with folic acid, but admittedly had not done so for 30 years, a diagnosis of MIOM was made.

Blood tests conducted four months prior and at presentation (see Table II) indicated impaired kidney function, limiting MTX excretion and low plasma albumin, increasing the free fraction of MTX. Additionally, drug interactions with enalapril and pantoprazole likely further hindered MTX excretion.

The patient was conclusively diagnosed with MIOM, prompting the discontinuation of MTX and supplementation with 10mg folic acid/week. Symptomatic treatment with topical lidocaine facilitated uneventful healing of the ulcers.

DISCUSSION

Mechanism of action of MTX: antineoplastic and anti-inflammatory effects

Methotrexate (MTX) is a widely used first-line therapy for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), despite ongoing debate regarding its anti-inflammatory effects.4,10 Some evidence suggests that MTX exerts both anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative effects by inhibiting enzymes involved in folate, methionine, adenosine and de novo nucleotide synthesis pathways.9,11 MTX works by irreversibly binding to and competitively inhibiting dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), which in turn inhibits the conversion of dihydrofolate (DHF) to tetrahydrofolate (THF), resulting in reduced nucleic acid synthesis.6,8,9

However, the inhibition of aminoimidazole carboxamide ribonucleotide transformylase (AICART), an enzyme involved in nucleotide biosynthesis, has been found to have the greatest anti-inflammatory effect.10 By inhibiting AICART, the accumulation of its substrate, AICART ribonucleotide (ZMP), occurs, leading to the inhibition of adenosine deaminase and increased levels of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and adenosine, which possess significant anti-inflammatory properties.9,10,12

Moreover, thymidylate synthase (TS) inhibition results in the depletion of deoxythymidine triphosphate, leading to cell death due to thymine starvation.12

Pharmacokinetics of MTX

MTX is actively absorbed in the proximal jejunum by the reduced folate carrier 1 (RFC1) transporter.13,14 Maximum plasma concentrations are reached within 0.75 to 2 hours of administration, which may be delayed but not reduced, by food intake.13,14 Because of the variable absorption, oral bioavailability ranges from 30%-90%,13 but is likely unimportant in LDMTX treatment.10 Only a small portion of MTX (10%) is hydroxylated to a less active metabolite in the liver.14

MTX is moderately plasma protein bound (35%-50% is bound to albumin),10 and is not readily displaced, or impacted by low albumin levels in the elderly.14 LDMTX is distributed to extravascular tissue compartments such as the kidneys, liver and synovia, exhibiting a half-life of around 1 hour.14 Because of its water solubility, MTX distribution varies according to the intracellular water volume, which may be reduced in the elderly, but offset by a decrease in renal clearance.14

MTX is efficiently transported within erythrocytes, white blood cells, hepatocytes and synoviocytes by RFC1, where it undergoes polyglutamation to form MTX-polyglutamate (PG). This process establishes an intracellular reservoir of MTX, allowing for weekly dosing, but also renders these cells more susceptible to the effects of MTX.13,14 Measuring MTX-PG levels in red blood cells (RBCs) is a more accurate way to estimate the effective MTX dose, as RBCs cannot produce MTX-PG and it is indicative of MTX levels in the bone marrow during erythroblast maturation.10

Renal excretion is the primary route of elimination for MTX, with more than 80% excreted intact in urine.10,13 However, there is significant inter-individual variability due to differences in tubular secretion and reabsorption, which may become saturated.13,14

Furthermore, long-term MTX administration can decrease renal clearance of both MTX and creatinine, as the increase in plasma adenosine concentrations may affect adenosine receptors in the kidneys.13,14 The remaining MTX dose is eliminated through bile.13

Adverse effects associated with MTX use

MTX is generally considered a safe drug, with a favourable side-effect profile in which serious adverse effects are rarely encountered.15,16 The frequency and severity of adverse effects of LDMTX vary depending on factors such as dosage, renal and hepatic dysfunction, and individual patient tolerance.17 These adverse effects can be attributed to either direct gastrointestinal and bone marrow toxicity, mediated by folate antagonism, with symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, oral mucositis and myelosuppression, or due to idiosyncratic or allergic reactions like pneumonitis. Additionally, long-term treatment with MTX can lead to liver or cardiovascular disease due to hyper-homocysteinemia.17

Pathogenesis of oral mucositis due to MTX use

The antiproliferative effect of MTX renders rapidly dividing mucosal and bone marrow cells susceptible to common side effects like myelosuppression and mucositis.9,18 MTX may exacerbate oral mucosal toxicity through salivary secretion, with salivary MTX levels potentially predicting oral ulceration.3 However, this perspective is not widely accepted in the pathogenesis of chemotherapy-induced mucositis.19

The outdated view that basal epithelial cell death and lack of renewal alone cause atrophic, ulcerated mucosa has been replaced by a five-phase model explaining oral mucositis development.19-22 During the initiation phase, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress develop, inducing transcription factors NF-kB and STAT3, which activate genes transcribing tissue-damage-mediating cytokines.20 Damaged cells release molecules that provoke and perpetuate inflammation.19,20

In the primary damage response phase, DNA strand breaks lead to direct cell death.20 Signalling continues among connective tissue, endothelial cells and inflammatory infiltrates in the submucosa, increasing NF-kB transcription and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, endothelial growth factors and cyclooxygenases.20 Damage to connective tissue fibrin activates matrix metalloproteinases, resulting in basal epithelial cell apoptosis.19,20

Signal amplification and biological feedback sustain a cascade of damaging mediators. TNF stimulates NF-kB, pro-inflammatory cytokines activate the metalloproteinase pathway, and cellular cross-talk persists.19,20

Chemotherapy's apoptotic and necrotic effects halt epithelial proliferation, leading to mucosal erosions and ulcerations. Bacteria colonise the ulcers, attracting more inflammatory cells and stimulating macrophages to produce additional pro-inflammatory cytokines.20

Finally, healing occurs as extracellular matrix signalling stimulates epithelial proliferation, migration and differentiation.20

Risk factors which influence susceptibility to adverse effects of MTX use

Various factors may affect a patient's susceptibility to the adverse effects of LDMTX.

A lack of folate can increase the toxicity of MTX in the oral mucosa, and inadequate supplementation with folic acid during treatment can further increase the risk of oral mucositis.7,17,3,16-18,23 Supplementation with folic acid can reduce MTX-induced mucosal side effects by 79% and significantly reduce the risk of pancytopenia.24,25 While Case 5 did not supplement with folic acid, her development of MIOM after 30 years suggests that folate deficiency was not the cause. All of the other cases took 5mg of folic acid daily. There is no dose-response relationship between adverse effects and the weekly dose or duration of LDMTX use.25,16 However, the majority of studies report on short-term toxicity, making it unclear to what extent these findings can be extrapolated to extended use of MTX.16

Inadvertent MTX overdosing due to daily, instead of weekly, use is another common cause of LDMTX oral toxicity,17,18,23,26,27 as was seen in Case 2. Given the risk of pancytopenia with daily dosing, it would have been prudent to perform a full blood count.28 Fortunately, the patient made a full recovery. Education is necessary for both patients and practitioners to prevent medication dosing errors and reduce drug interactions.27

Other than these treatment errors, the strongest predictor of experiencing adverse effects is renal impairment. Renal impairment causes MTX to be eliminated ineffectively, leading to increased systemic exposure to the drug.25,29-31 With advancing age and extended use of MTX, renal excretion of MTX tends to slow down.31 In the elderly population, liver dysfunction and reduced renal function, along with comorbidities and medication use that may cause kidney injury, significantly increase the risk of MTX toxicity.31 Reduced plasma protein levels will increase the availability of MTX, change intravascular oncotic pressure and delay MTX clearance.31 Hypoalbuminemia has been associated with the development and severity of pancytopenia,25 which likely contributed to the experience of MIOM in both Case 1 and Case 5, who were elderly patients with impaired kidney function and low albumin levels, leading to reduced MTX clearance and increased MTX toxicity.

MTX is subject to various drug interactions that alter its renal clearance, liver metabolism and pharmacodynamics, necessitating cautious use at low doses and with careful supervision.17,31 These interactions include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin and ibuprofen, antimicrobials such as penicillin, amphotericin, aminoglycosides, ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, sedatives, anticonvulsants, cyclosporine and probenecid.3,32,5,17,31,14,33 NSAIDs reduce renal blood flow and glomerular filtration, competitively inhibit active tubular secretion of MTX, and displace MTX from albumin, and may therefore contribute to myelosuppression.25 Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) interfere with MTX renal elimination by affecting renal hemodynamics, tubular secretion, and reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR).31 Diuretics also reduce renal blood flow and GFR, and compete with MTX for renal tubular secretion,31 while proton pump inhibitors (PPI) also reduce renal clearance.34 Furthermore, the anti-folate effects of MTX can be intensified by nitrous oxide, so concurrent use, such as during inhalational sedation, should be avoided.17 Drug interactions likely resulted in the MIOM experienced by Case 3 and 4, where the combined use of NSAIDs, PPI, anticonvulsants and diuretics reduced renal clearance of MTX, resulting in MTX toxicity.

Finally, the susceptibility of an individual to methotrexate MIOM may be influenced by polymorphisms in genes encoding proteins and enzymes involved in MTX transport, metabolism, folate metabolism or neutralisation of reactive oxygen species (ROS).30,31 The indirect inhibition of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) by MTX, an enzyme involved in folate-dependent DNA synthesis, may result in increased MTX toxicity due to missense mutations in genes that encode this enzyme.31,35 Additionally, mutations in the ARID5B gene have been associated with altered MTX processing, toxicity, albumin levels and liver toxicity.36,37 Genetic variations in the UGT1A1 gene, which encodes the enzyme responsible for bilirubin metabolism, may also increase MTX systemic exposure and bilirubin production.30 However, it is important to note that the impact of these polymorphisms has been primarily demonstrated in high-dose MTX use and may not apply to low-dose MTX use risks. Polymorphisms in genes encoding proteins involved in the general pathogenesis of mucositis may also increase the risk of this toxicity. Deletion polymorphisms in genes encoding glutathione-S-transferases, for example, reduce enzyme activity and increase susceptibility to oxidative stress, resulting in greater oral mucosal toxicity.20,38,39 Epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation, histone modifications and non-coding RNA regulation, also play a critical role in regulating gene activity and impacting MTX metabolism and toxicity.31

ORAL FEATURES OF METHOTREXATE-INDUCED ORAL MUCOSITIS

Grading of oral mucositis

The World Health Organisation (WHO) and National Cancer Institute (NCI) scales are widely employed for grading the severity of oral mucositis.40 The WHO scale is user-friendly and depends on the clinician's observation of ulceration and the patient's ability to consume solid foods.41 In contrast, the NCI-Common Toxicity Criteria takes into account the clinical presentation of oral mucositis and requires a comprehensive assessment of erythema, oedema and ulceration, as well as the patient's ability to maintain hydration and nutrition.42 Despite this, both scales classify all of our patients as having moderate (Grade 2) mucositis, characterised by the presence of ulcers while still being able to eat, albeit with a shift towards soft and bland foods.

Prevalence and clinical characteristics

Oral mucositis is the fourth most frequent side effect of LDMTX use, accounting for approximately 3% of patients who discontinue treatment.29,7 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis revealed an 8% prevalence of MIOM in patients receiving treatment for RA,43 while an earlier review reported a 14% prevalence.7 However, some authors have reported much higher rates, ranging from 36.2% to 60.7%.44-46 The studies included in the systematic review by Lalani et al in 2020 primarily relied on patients self-reporting their ulcer experience,43 while clinical assessment by a stomatologist resulted in the highest prevalence rate.46

The oral mucositis of LDMTX treatment can manifest as frank ulceration, redness and pain,44,45 ranging from WHO grades 1 to 4.27,44,47 These ulcers are often deep and irregular, appearing either as localised or generalised, non-healing ulcers, or exhibiting features of aphthous-like ulcers and lichenoid lesions.7,44 Skin involvement and systemic symptoms may be present.47

It is important to note that the mucositis associated with LDMTX use is less severe than the widespread, acute toxic reactions typically observed with high-dose MTX treatment,7 even though multiple ulcers are commonly reported.3 Affected patients may experience significant impairment in their quality of life due to difficulties with eating, speaking and maintaining proper oral hygiene.17 Poor nutrition can further exacerbate folate deficiency, resulting in weight loss and a decline in overall health.18

Oral mucositis resulting from LDMTX use can occur rapidly, within five days to one month, due to incorrect daily administration,27,47-50 or much later.7,46 As a result, the condition may not always be identified as the cause,7 as in our cases where it developed many years after starting the medication. In addition to the typical features of oral mucositis, destructive lymphoma-like lesions,5,7,51 erythema multiforme (EM),49,52 and atypical herpes simplex virus mucocutaneous infection53 have been reported.

It is possible that MTX may not be solely responsible for all of the observed mucosal lesions, as it may also have prevented the healing of traumatic ulcers, lichenoid drug reactions or infections.7 Upon discontinuation of MTX, the ulcers, lymphoproliferative disorders and EM typically heal within two to four weeks,5,7,23,47,54 with a median healing time of 19.9 days reported by Chomorro et al 2019,3 which was also our experience. However, long-term drug administration can exacerbate the lesions,23 and may be complicated by concomitant myelosuppression.19

Diagnosis of methotrexate-induced oral mucositis

MIOM diagnosis depends on the patient's clinical presentation, medical history, drug history and may be supplemented with special investigations.47,55 It is important to verify the patient's MTX dose since accidental overdosing is common.3,47 All the patients presented in this study had RA and had been taking LDMTX for varying periods, in conjunction with a variety of pharmacological agents to manage both their RA and other comorbidities. The ulcers in these patients were painful, distributed widely over the non-keratinised and keratinised mucosa, surrounded by erythema, covered by a fibrinopurulent membrane, and appeared to be preceded by vesicles (see Table III).

Special investigations are often employed to rule out alternative explanations for oral mucosal ulceration or to gather additional evidence related to MTX toxicity. These investigations should include a FBC to evaluate bone marrow function,47 as myelosuppression has been observed in more than 50% of patients with MIOM,3 while 80% of those with pancytopenia present with oral mucositis.28 A reduced eGFR may explain the inadequate clearance of MTX, and hypoalbuminemia may contribute to a larger free fraction of MTX.27,25 These assessments were particularly useful in the management of Cases 1 and 5, where reduced eGFR and hypoalbuminemia likely played a role in MTX toxicity.

Biopsies with histopathological assessment are usually performed infrequently (29%)3 and may be useful to rule out other immune-mediated vesiculobullous diseases. However, in the presence of effective immune suppression with LDMTX therapy, other immune-mediated diseases are unlikely to be the cause, while infective diseases may occur due to immune suppression. The histologic features of MIOM are nonspecific, but mild regenerative epithelial dysplasia, apoptotic figures in all epithelial layers, and a lichenoid inflammatory reaction may be observed in the connective tissue7,47 as was seen in Case 1 and 4. Some may argue against performing invasive investigations before the FBC is assessed, given the risk of thrombocytopenia and neutropenia.

Treatment of MTX-induced oral mucositis

Mucositis, specifically MIOM, lacks a universally accepted protocol for treatment.19,3,56 As per a recent review by Chomorro et al (2019), most patients are typically treated by either discontinuing MTX alone, or by adding folic acid, topical corticosteroids and antibiotics.3 The dose-response relationship between LDMTX use and oral ulceration is ambiguous, and the efficacy of dose-reduction strategies remains uncertain.44,46

Symptomatic relief may be provided to patients while the ulcers heal spontaneously following MTX withdrawal, with topical analgesics such as 2% viscous lidocaine, corticosteroids, covering and antiseptic agents,7,27 essentially replicating the "magic mouthwash" protocols used by oncology units.20 However, the efficacy of these combinations may not be greater than a saltwater rinse.20 Alternatively, key role players in the pathogenesis of oral mucositis may be targeted. Accordingly, L-glutamine, amifostine, benzydamine hydrochloride, N-acetylcysteine, keratinocyte growth factor (palifermin) and COX-2 inhibitors have been proposed to reduce ROS, suppress NF-KB activation and reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine production.19 Nutritional support should be provided through liquid dietary supplements, and the patient's oral hygiene should be maintained through effective plaque control measures.21 Despite the antimicrobial benefit of chlorhexidine or the healing properties of low-level laser therapy, these modalities are not supported for treating oral chemotherapy-induced mucositis.21

Topical corticosteroids are frequently employed to treat immune-mediated oral mucosal diseases, and they may be utilised to treat drug-induced oral ulcers if mediated by an immune mechanism.57 Although neither Case 1, 2 or 4 demonstrated any benefit from topical or systemic corticosteroid use, Ahmed et al (2019) reported that topical clobetasol led to significant reductions in pain, mucositis score, ulcer size and number within a week, while continuing with LDMTX treatment.56 However, human platelet lysate proved to be much more effective and faster at achieving these results.56 Platelet concentrates are rich in growth factors that promote angiogenesis and tissue regeneration.56

MIOM essentially mimics folate deficiency.1,58 Supplementation with exogenous folate during MTX therapy for RA can reduce gastrointestinal and hepatic side effects, as well as the risk of patient withdrawal. Additionally, it appears to protect against the risk of MIOM, although this has not been conclusively proven, while still maintaining the effectiveness of MTX in treating RA.59 Folic acid is the preferred supplement as it is more cost-effective and has a wider safety margin than folinic acid.7,58

Folinic acid is fully metabolically active and does not require DHFR.58 As a result, folinic acid, and its synthetic counterpart, leucovorin, are employed in MTX rescue therapy because they can displace MTX from DHFR and restore intracellular folate stores with fully reduced folate.1,27,58 Intravenous leucovorin is administered to manage LDMTX-induced pancytopenia,28 which may be further supplemented with filgrastim (granulocyte colony-stimulating factor) to recover bone marrow function.60

However, according to Endresen (2001), not all patients may require folate supplementation, as dietary intake may be sufficient.58 In fact, Case 5 did not receive folic acid supplementation and only experienced adverse effects due to renal impairment. Nonetheless, all of the patients studied by Pedrazas et al (2010), who were not taking folic acid, presented with oral mucositis,46 and 15% of patients who presented with pancytopenia, were not taking folic acid.28 To identify patients who require folate supplementation, an increase in mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and subsequent determination of serum and erythrocyte folate may be used, with supplementation recommended at a ratio of 1-2mg of folic acid per day, 24 hours apart from the weekly MTX dose.58

The folate-to-MTX ratio can be increased to 3:1 if necessary,58 with oral mucositis often improving on higher doses.58 However, even with higher weekly doses of MTX (25mg), routine use of more than 10mg of folic acid per week does not seem justified, as there are no additional benefits or differences in adverse effects.61 It is worth noting that the cases presented here (1-4) all took 5mg of folic acid per day (35mg/week) and still developed MIOM, but may have done so much earlier if they did not take folic acid. Given the significant risks associated with pancytopenia, it could be argued that standard folic acid supplementation should be considered for all patients.28

Before starting LDMTX treatment, it is essential to obtain an FBC and assess liver and kidney function.2 The FBC, creatinine and liver function should be evaluated every 2-4 weeks for the initial three months, then every 8-12 weeks for the subsequent 3-6 months, and thereafter every 12 weeks.4 Regular monitoring is crucial because pancytopenia may only arise several years after initiating treatment.25,28

CONCLUSION

These clinical cases illustrate the necessity for dentists to identify the manifestations of MIOM. Oral mucositis can emerge after extensive use of LDMTX, due to adverse drug interactions, medication errors and compromised liver and kidney function. MIOM gives rise to severe oral discomfort, hindering patients from consuming food and liquids as they typically would. The oral mucosa may exhibit numerous ulcers, distributed haphazardly, which can mimic vesiculobullous diseases, such as mucous membrane pemphigoid. It is crucial for dentists to collaborate closely with the patient's rheumatologist for dose adjustments or drug substitutions, and to monitor the systemic consequences of MTX toxicity. Dentists may provide symptomatic relief, and assist with mechanical and chemical plaque removal while the patient is unable to perform personal plaque control, thereby reducing the oral microbial burden which may exacerbate disease progression.

REFERENCES

1. Deeming GM, Collingwood J, Pemberton MN. Methotrexate and oral ulceration. Br Dent J. 2005;198(2):83-5 [ Links ]

2. Bykerk VP, Akhavan P Hazlewood GS, Schieir O, Dooley A, Haraoui B, et al. Canadian Rheumatology Association recommendations for pharmacological management of rheumatoid arthritis with traditional and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(8):1559-82 [ Links ]

3. Chamorro-Petronacci C, García-García A, Lorenzo-Pouso AI, Gómez-García FJ, Padín-Iruegas ME, Gándara-Vila P, et al. Management options for low-dose methotrexate-induced oral ulcers: A systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2019;24(2):e181-e9 [ Links ]

4. Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, Jr, Akl EA, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(1):1-26 [ Links ]

5. Katsoulas N, Chrysomali E, Piperi E, Levidou G, Sklavounou-Andrikopoulou A. Atypical methotrexate ulcerative stomatitis with features of lymphoproliferative like disorder: Report of a rare ciprofloxacin-induced case and review of the literature. J Clin Exp Dent. 2016;8(5):e629-e33 [ Links ]

6. Bedoui Y Guillot X, Sélambarom J, Guiraud P, Giry C, Jaffar-Bandjee MC, et al. Methotrexate an Old Drug with New Tricks. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(20) [ Links ]

7. Kalantzis A, Marshman Z, Falconer DT, Morgan PR, Odell EW. Oral effects of low-dose methotrexate treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100(1):52-62 [ Links ]

8. Torres RP, Santos FP, Branco JC. Methotrexate: Implications of pharmacogenetics in the treatment of patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. ARP Rheumatol. 2022;1(3):225-9 [ Links ]

9. Chan ES, Cronstein BN. Methotrexate - how does it really work? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6(3):175-8 [ Links ]

10. Inoue K, Yuasa H. Molecular basis for pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis therapy. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2014;29(1):12-9 [ Links ]

11. Horn HM, Tidman MJ. The clinical spectrum of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146(2):267-74 [ Links ]

12. Dervieux T, Furst D, Lein DO, Capps R, Smith K, Walsh M, et al. Polyglutamation of methotrexate with common polymorphisms in reduced folate carrier, aminoimidazole carboxamide ribonucleotide transformylase, and thymidylate synthase are associated with methotrexate effects in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(9):2766-74 [ Links ]

13. van Roon EN, van de Laar MA. Methotrexate bioavailability. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28(5 Suppl 61):S27-32 [ Links ]

14. Maksimovic V, Pavlovic-Popovic Z, Vukmirovic S, Cvejic J, Mooranian A, Al-Salami H, et al. Molecular mechanism of action and pharmacokinetic properties of methotrexate. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47(6):4699-708 [ Links ]

15. Lopez-Olivo MA, Siddhanamatha HR, Shea B, Tugwell P, Wells GA, Suarez-Almazor ME. Methotrexate for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(6):Cd000957 [ Links ]

16. Mazaud C, Fardet L. Relative risk of and determinants for adverse events of methotrexate prescribed at a low dose: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(4):978-86 [ Links ]

17. Dervisoglou T, Matiakis A. Oral Ulceration Due to Methotrexate Treatment: A Report of 3 Cases and Literature Review. Balkan Journal of Dental Medicine. 2015;19 [ Links ]

18. Goodman SM, Cronstein BN, Bykerk VP. Outcomes related to methotrexate dose and route of administration in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33(2):272-8 [ Links ]

19. Sonis ST. The pathobiology of mucositis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(4):277-84 [ Links ]

20. Sonis ST. Oral mucositis. Anticancer Drugs. 2011;22(7):607-12 [ Links ]

21. Lalla RV, Brennan MT, Gordon SM, Sonis ST, Rosenthal DI, Keefe DM. Oral Mucositis Due to High-Dose Chemotherapy and/or Head and Neck Radiation Therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2019;2019(53) [ Links ]

22. Sonis ST. Pathobiology of oral mucositis: novel insights and opportunities. J Support Oncol. 2007;5(9 Suppl 4):3-11 [ Links ]

23. Hanakawa H, Orita Y, Sato Y, Uno K, Nishizaki K, Yoshino T. Large ulceration of the oropharynx induced by methotrexate-associated lymphoproliferative disorders. Acta Med Okayama. 2013;67(4):265-9 [ Links ]

24. Ortiz Z, Shea B, Suarez-Almazor ME, Moher D, Wells GA, Tugwell P. The efficacy of folic acid and folinic acid in reducing methotrexate gastrointestinal toxicity in rheumatoid arthritis. A metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(1):36-43 [ Links ]

25. Mori S, Hidaka M, Kawakita T, Hidaka T, Tsuda H, Yoshitama T, et al. Factors Associated with Myelosuppression Related to Low-Dose Methotrexate Therapy for Inflammatory Rheumatic Diseases. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0154744 [ Links ]

26. Yélamos O, Català A, Vilarrasa E, Roé E, Puig L. Acute severe methotrexate toxicity in patients with psoriasis: a case series and discussion. Dermatology. 2014;229(4):306-9 [ Links ]

27. Shrestha R, Ojha SK, Jha SK, Jasraj R, Fauzdar A. Methotrexate-Induced Mucositis: A Consequence of Medication Error in a Rheumatoid Arthritis Patient. Cureus. 2023;15(9):e46290 [ Links ]

28. Ajmani S, Preet Singh Y, Prasad S, Chowdhury A, Aggarwal A, Lawrence A, et al. Methotrexate-induced pancytopenia: a case series of 46 patients. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017;20(7):846-51 [ Links ]

29. Attar SM. Adverse effects of low dose methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis patients. A hospital-based study. Saudi Med J. 2010;31(8):909-15 [ Links ]

30. Yang Y Liu Z, Chen J, Wang X, Jiao Z, Wang Z. Factors influencing methotrexate pharmacokinetics highlight the need for individualized dose adjustment: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2024;80(1):11-37 [ Links ]

31. Li W, Mo J, Yang Z, Zhao Z, Mei S. Risk factors associated with high-dose methotrexate induced toxicities. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2024;20(4):263-74 [ Links ]

32. Colebatch AN, Marks JL, van der Heijde DM, Edwards CJ. Safety of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and/or paracetamol in people receiving methotrexate for inflammatory arthritis: a Cochrane systematic review. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2012;90:62-73 [ Links ]

33. Uwai Y, Saito H, Inui K-i. Interaction between methotrexate and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in organic anion transporter. European Journal of Pharmacology 2000;409(1):31-6 [ Links ]

34. Tao D, Wang H, Xia F, Ma W. Pancytopenia Due to Possible Drug-Drug Interactions Between Low-Dose Methotrexate and Proton Pump Inhibitors. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2022;14:75-8 [ Links ]

35. Yousef AM, Farhad R, Alshamaseen D, Alsheikh A, Zawiah M, Kadi T. Folate pathway genetic polymorphisms modulate methotrexate-induced toxicity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2019;83(4):755-62 [ Links ]

36. Csordas K, Lautner-Csorba O, Semsei AF, Harnos A, Hegyi M, Erdelyi DJ, et al. Associations of novel genetic variations in the folate-related and ARID5B genes with the pharmacokinetics and toxicity of high-dose methotrexate in paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(3):410-20 [ Links ]

37. Xu M, Wu S, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Wang X, Wei C, et al. Association between high-dose methotrexate-induced toxicity and polymorphisms within methotrexate pathway genes in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1003812 [ Links ]

38. Hahn T, Zhelnova E, Sucheston L, Demidova I, Savchenko V, Battiwalla M, et al. A deletion polymorphism in glutathione-S-transferase mu (GSTM1) and/or theta (GSTT1) is associated with an increased risk of toxicity after autologous blood and marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(6):801-8 [ Links ]

39. Ambrosone CB, Tian C, Ahn J, Kropp S, Helmbold I, von Fournier D, et al. Genetic predictors of acute toxicities related to radiation therapy following lumpectomy for breast cancer: a case-series study. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8(4):R40 [ Links ]

40. Sonis ST, Elting LS, Keefe D, Peterson DE, Schubert M, Hauer-Jensen M, et al. Perspectives on cancer therapy-induced mucosal injury: pathogenesis, measurement, epidemiology, and consequences for patients. Cancer. 2004;100(9 Suppl):1995-2025 [ Links ]

41. World Health O. WHO handbook for reporting results of cancer treatment. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1979 [ Links ]

42. Institute NIoHNC. National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE): U.S.DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES; 2009 [updated June 2010. 4.0:[Available from: http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf [ Links ]

43. Lalani R, Lyu H, Vanni K, Solomon DH. Low-Dose Methotrexate and Mucocutaneous Adverse Events: Results of a Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(8):1140-6 [ Links ]

44. Magdy E, Ali S. Stratification of methotrexate-induced oral ulcers in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Spec Care Dentist. 2021;41(3):367-71 [ Links ]

45. Ince A, Yazici Y, Hamuryudan V, Yazici H. The frequency and clinical characteristics of methotrexate (MTX) oral toxicity in rheumatoid arthritis (RA): a masked and controlled study. Clin Rheumatol. 1996;15(5):491-4 [ Links ]

46. Pedrazas CH, Azevedo MN, Torres SR. Oral events related to low-dose methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Braz Oral Res. 2010;24(3):368-73 [ Links ]

47. Troeltzsch M, von Blohn G, Kriegelstein S, Woodlock T, Gassling V, Berndt R, et al. Oral mucositis in patients receiving low-dose methotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: report of 2 cases and literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;115(5):e28-33 [ Links ]

48. Hocaoglu N, Atilla R, Onen F, Tuncok Y. Early-onset pancytopenia and skin ulcer following low-dose methotrexate therapy. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2008;27(7):585-9 [ Links ]

49. Rampon G, Henkin C, Jorge VM, Almeida HL, Jr. Methotrexate-induced mucositis with extra-mucosal involvement after acidental overdose. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93(1):155-6 [ Links ]

50. Nam JW. Perforation in Submucous Cleft Palate Due to Methotrexate-Induced Mucositis in a Patient With Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29(3):772-3 [ Links ]

51. Horie N, Kawano R, Kaneko T, Shimoyama T. Methotrexate-related lymphoproliferative disorder arising in the gingiva of a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Aust Dent J. 2015;60(3):408-11 [ Links ]

52. Omoregie FO, Ukpebor M, Saheeb BD. Methotrexate-induced erythema multiforme: a case report and review of the literature. West Afr J Med. 2011;30(5):377-9 [ Links ]

53. Alghamdi N, Albaqami A, Alharbi A. Atypical Presentation of Herpes Simplex Virus Infection in an Immunocompromised Patient. Cureus. 2023;15(4):e37465 [ Links ]

54. Warner J, Brown A, Whitmore SE, Cowan DA. Mucocutaneous ulcerations secondary to methotrexate. Cutis. 2008;81(5):413-6 [ Links ]

55. Scully C, Sonis S, Diz PD. Oral mucositis. Oral Dis. 2006;12(3):229-41 [ Links ]

56. Ahmed EM, Ali S, Gaafar SM, Rashed LM, Fayed HL. Evaluation of topical human platelet lysate versus topical clobetasol in management of methotrexate-induced oral ulceration in rheumatoid arthritis patients: Randomized-controlled clinical trial. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;73:389-94 [ Links ]

57. González-Moles MA, Scully C. Vesiculo-erosive oral mucosal disease-management with topical corticosteroids: (1) Fundamental principles and specific agents available. J Dent Res. 2005;84(4):294-301 [ Links ]

58. Endresen GK, Husby G. Folate supplementation during methotrexate treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. An update and proposals for guidelines. Scand J Rheumatol. 2001;30(3):129-34 [ Links ]

59. Shea B, Swinden MV, Tanjong Ghogomu E, Ortiz Z, Katchamart W, Rader T, et al. Folic acid and folinic acid for reducing side effects in patients receiving methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(5):Cd000951 [ Links ]

60. Schelzel G, Palicherla A, Tauseef A, Millner P Low-dose methotrexate toxicity leading to pancytopenia: leucovorin as a rescue treatment. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2024;37(2):339-43 [ Links ]

61. Dhir V, Sandhu A, Kaur J, Pinto B, Kumar P, Kaur P, et al. Comparison of two different folic acid doses with methotrexate - a randomized controlled trial (FOLVARI Study). Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17(1):156 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr Jeanine Fourie

Tel: 012 319 2312

Email: jeanine.fourie@up.ac.za

Author's contribution

1. Dr J Fourie - introduction, conclusion, case studies, pathogenesis of oral mucositis, revision of manuscript

2. Dr D Laubscher - pathogenesis, risk factors, use of MTX as DMARD

3. Mr Simelane - diagnosis and treatment