Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Dental Journal

On-line version ISSN 0375-1562Print version ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.80 n.3 Johannesburg Apr. 2025

https://doi.org/10.17159/sadj.v80i03.18798

RESEARCH

Access to emergency drugs and equipment among South African dentists

S SwanepoelI; KH MerboldII; T ParbhooIII

IBChD, PGDipDent (Oral Surgery), MSc (Dent) (Oral Surgery) (Pret), PDD (Implantology) (UWC), Department of Maxillo-Facial and Oral Surgery, School of Dentistry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria and private dental practice, South Africa. ORCID: 0009-0007-3836-9996

IIBChD, PGDipDent (Oral Surgery), MSc (Dentistry) (Pret), Department of Maxillo-Facial and Oral Surgery, School of Dentistry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa. ORCID: 0000-0003-4554-2690

IIIBChD (Pret), Head: Clinical Support Services, South African Dental Association, Pretoria, South Africa. ORCID: 0009-0004-6168-5717

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: General dental practitioners must be proficient In using emergency drugs and equipment during medical emergencies. Concerns persist about the adequacy of South African general dental practitioners' emergency supplies

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES: To evaluate South African general dental practitioners' access to emergency drugs and equipment and develop a medical emergency drug and equipment list for practitioners

METHODS: A prospective mixed-methods study employed a Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices and Beliefs (KAPB) survey among South African general dental practitioners. Data analysis included descriptive statistics and frequency distributions in Microsoft® Excel®

RESULTS: Emergency services were available to only (n=237, 65.8%) of participants. Sphygmomanometers were available to (n=180, 50%), with limited access to automated external defibrillators (n=38, 10.6%). No tranexamic acid was available to any participant and aspirin was accessible to (n=161, 44.7%). Oxygen supplies were recorded as (n=106, 29.4%) and (n=132, 36.7%) had access to EpiPens®. Reliance on external services (n=46, 35.1%), financial constraints (n=39, 29.8%), drug expiration (n=26, 19.8%), negligence (n=37, 13.7%), lack of confidence (n=18, 13.7%) and maintenance challenges (n=5, 3.8%) hindered procurement of emergency supplies

CONCLUSION: South African general dental practitioners lack confidence in using emergency drugs and equipment, hindered by complacency and cost-related concerns. This article proposes an emergency drug and equipment list, and incorporates a dental emergency flowchart for general dental practitioners

Keywords: General dental practitioners, medical emergency management, emergency drugs and equipment, preparedness.

INTRODUCTION

A medical emergency (ME) can occur at any time, though the risk of medical emergencies (MEs) occurring in a dental setting may be greater during invasive oral surgical procedures. It is therefore essential that general dental practitioners (GDPs) are prepared to appropriately manage emergency situations.1 It is further the responsibility of GDPs to ensure that all auxiliary dental personnel are appropriately educated and trained to assist in the management of in-office MEs.2 This may reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with MEs during dental treatment.2-3,14

In France and Belgium, GDPs are confronted with at least one ME in a 12-month period.4 In the US, the American Dental Association Council of Scientific Affairs revealed that in the lifetime of every four GDPs, three are confronted with patients who present with a life-threatening ME.5 The association further states that one in every 20 GDPs may be confronted with a patient in cardiac arrest.5 Atherton reported that GDPs in Great Britain encounter MEs on average once every three to four years.6-7 Moreover, a survey conducted by Malamed revealed that 96.6% of GDPs encountered an in-office ME over an average practice lifetime of 20 to 30 years.8 Reports reveal that the most common MEs in dental practice are anaphylaxis, angina, asthma attacks, fainting, a hypertensive crisis, hyperventilation, hypoglycaemia, orthostatic hypotension, pre-syncope, seizures and vasovagal syncope.2,8-12 Even though the majority may not impose life-threatening outcomes, appropriately managing such events should not be of less importance than dental intervention itself.13 According to the American Heart Association (AHA) nearly 350,000 patients succumb to cardiac arrest annually in the US15-16 and therefore recommends that every healthcare professional's office in the US should be equipped with an automated external defibrillator (AED). Past studies have revealed that GDPs lack confidence to manage MEs.17 This may be due to a lack of training or the absence of appropriate emergency drugs and equipment.10,18

The prevalence of MEs is increasing in dental practice, with several studies suggesting that emergency management skills of GDPs are substandard, even if practitioners may have positive self-reported proficiency levels.9-11,19-24 The Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at the Brooklyn Hospital Center in New York developed an in-depth guide in 2016 on preparing for emergency medical situations in dental settings.2 This report provides the GDP with a list of emergency drugs, equipment and checklists/worksheets advised for the dental office. They further suggested using impromptu emergency scenarios and having emergency contact details accessible to all staff members.2 Other independent studies appear to have drawn similar conclusions.25-26

Locally, the Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa serves as an elective coordinating body with the aim to promote and direct theoretical education and practical training in resuscitation.27 Resources such as academic publications, algorithms in systems of care, and emergency equipment supplier contact details are available publicly.28 The South African Dental Association (SADA) furthermore provides an open access dental emergency flowchart on their website.29 This chart provides a step-by-step process for the management of MEs and is suitable for use by all GDPs and their staff. A section of this study delved into a more recent review of this flowchart.

Owen and Mizra conducted a study in South Africa (SA) in 2013 to assess the preparedness of GDPs to manage MEs.30 Their study reported that 37% of participants had encountered multiple MEs over a 12-month period and 15% of participants had no access to emergency armamentaria. These authors also established that private GDPs in SA do not have sufficient access to emergency equipment and drugs in their practices.30 To our knowledge, the recommendations of Owen and Mizra regarding the formulation of an emergency equipment and drug list has not been implemented in general dental practice in SA. Therefore, we saw it as essential to re-investigate the current situation in SA regarding GDPs' access to and knowledge of the use of emergency drugs and equipment in the management of MEs. We aimed to expand on Owen and Mizra's study by being more inclusive. A Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices and Beliefs (KAPB) survey aimed at GDPs from the public, private and academic sectors could provide a more accurate description and strengthen the previous researchers' recommendations.

METHODS

The study was approved by the Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee at the University of Pretoria (Reference no: 564/2021). In addition, it was conducted in accordance with the ethical biomedical research protocols of the World Association Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 (most recent update, October 2012). Given a target population of 6,059 it was essential that a sample size with a minimum of 358 participants be obtained to achieve results within an accuracy of 5% and a confidence interval of 95%. The sample size was formulated from guidelines for sample size estimation in clinical research as proposed by Hulley et al (2007).31 A mixed-methods prospective research design was employed for data collection through an anonymous, cross-sectional KAPB survey created using the Qualtrics DesignXMTM platform, which is provided by the University of Pretoria to support students in conducting academic research. The survey was validated through a structured process to ensure reliability and applicability to the study population which involved multivariate regression analysis to confirm survey components.68-71 Face validity was conducted to ensure that questions appear relevant and understandable to respondents. Content validity followed, where authors reviewed survey items for completeness which was subjected to a pilot study to enhance the survey's clarity and effectiveness based on feedback from the pilot study's respondents. The questionnaire was consecutively distributed, electronically, to GDPs in public and private sectors in all provinces in SA. Results were thereafter descriptively reported using frequency distributions and Microsoft® Excel® was employed for exploratory data analysis. Responses were thematically coded by using an open-ended coding strategy as proposed by Braun and Clarke.39 Variables were evaluated using simple descriptive statistics.

MEASUREMENTS

Quantitative assessment involved measurement of binary categorical dependent variables where participants had to indicate which emergency drugs and armamentaria they had at their disposal in their clinical setting and if they have access to ME services. Qualitative assessment from continuous numerical dependent variables consisted of independent individual structured reflections of open-ended questions to evaluate opinions on shortcomings regarding drugs and equipment in their respective clinical settings. This included thoughts on what the participants perceived the reasons are for a lack of drugs and equipment within their setting (if applicable). The assessment as part of the questionnaire was formulated based on review of AHA guidelines (2020).32-38

RESULTS

Four hundred and seventy participants completed the questionnaire. Response rate was 6.5% with an accuracy of 5% at 95% confidence interval. Three hundred and sixty respondents were included. Most participants had access to emergency medical services within their immediate vicinity (n=237, 65.8%). Exactly half of participants (n=180, 50.0%) had access to blood pressure machines (sphygmomanometers). Low accessibility to an AED was reported (n=38, 10.6%) and the availability of oxygen cylinders with standard fittings and oxygen masks was (n=106, 29.4%). Respondents demonstrated a proficiency in AED use of (n=71,19.7%) and EpiPens® (n=120, 33.3%). The drug most readily available was aspirin (n=161, 44.7%). Among the other emergency drugs, tranexamic acid was the least available, with zero availability. Figure I demonstrates the statistics that were recorded in terms of the listed emergency drugs and armamentaria: Adrenaline [1:1000/1:10 000] or EpiPen® (n=132, 36.7%), antihistamine (n=143, 39.7%), Corticosteroids/Cortisone (eg Prednisone) (n=87, 24.2%), Dextrose (n=117, 32.5%), Diazepam/Lorazepam (or similar) (n=79, 21.9%), Intralipid® 20% (n=18, 5%), Salbutamol/asthma pump/bronchodilator (n=98, 27.2%), pulse oximeter (n=140, 38.9%) and a thermometer (n=164, 45.6%). Zero percent of participants reported to have no access to emergency drugs and equipment.

Of the total of 360 participants (n=131, 33.9%) provided answers to the instruction "Give information as to why you think some items are not at your disposal" demonstrated in Figure II. A nearby medical centre for referrals was mentioned in (n=46, 35.1%) of these responses. Financial constraints hindered procurement for (n=39, 29.8%) responders and (n=26, 19.8%) reported drug expiration as a barrier to acquiring emergency drugs. In (n=37, 28.2%) of responses the participants mentioned that an indifferent attitude by staff or supervisors in the dental set-up contributed towards items not being available.

DISCUSSION

MEs are a concern in dentistry. It is crucial for every member of the dental team to understand their responsibilities and work in partnership with emergency medical providers. Awareness of the signs and symptoms of MEs, along with appropriate management of auxiliary staff, will enhance the efficacy of emergency management protocols.2-3 Patient safety may be improved through a solid grasp of emergency management principles, ongoing training in emergency care and frequent practice of first-aid skills.2,3,14,40-45 Many reports on MEs in dental offices worldwide have been published.6,47-51 Several studies have examined the skills and attitudes of GDPs in CPR, their preparedness for MEs and the availability of emergency drugs and equipment.23,45,52-54

Additionally, differences in the management of MEs in private, public and academic dental sectors have received limited attention. The objective of attaining a sample size of 358 responses set during the power calculation was slightly exceeded by obtaining 360 usable responses in order to obtain results within an accuracy of 5% and a confidence interval of 95% as proposed by Hulley et al (2007).31

The response rate of 6.4% was, however, very low. This may most likely be attributed to the study's voluntary nature and the comprehensive nature of the questionnaire. Some participants only partially completed the survey, possibly due to survey fatigue. It's worth noting that the response rate is lower compared to other studies because this study aimed to include GDPs across all provinces and sectors in SA. According to study findings by Bhayat et al,55 statistics from 2016 revealed a count of 6,125 GDPs. To enhance response rates, consecutive distributions were sent through Medpages International SA and SADA. The responses received met the minimum required sample size for a statistically significant outcome.

Access to medical emergency services

The majority of participants (n=237, 65.8%) had access to nearby emergency medical services. The type of service provided by GDPs may vary according to the area in which they practice. This service may include a healthcare response system which incorporates first responders/paramedics, ambulance services, a hospital department emergency room/ casualties, mobile clinics or doctors' rooms. It is comforting to know that almost two-thirds of GDPs have access to ME services. Those who, however, lack access to emergency medical services may be exposed to life-threatening risks as patients encounter unexpected complications in the dental office, whether procedure-related or not.

Access to emergency equipment

Just more than half of participants reported having access to blood pressure monitors (n=180, 50%). This is similar to the findings of a previously conducted South African study by Owen and Mizra, who reported that 51% of their participants had access.30 However, the accessibility to AEDs remains notably limited, with only (n=38, 10.6%) of GDPs having access. While the result is still worrisome it is again in line with Owen and Mizra30 for GDPs but higher when compared to an international study by Müller et al.10 Cost might be the motivating factor in this discrepancy. The low availability of AEDs in general dental practice likely indicates a lack of preparedness for sudden cardiac emergencies in dental settings. The availability of oxygen cylinders with standard fittings and oxygen masks was reported by (n=106, 29.4%) of GDPs, which is 12.6% less than that of Owen and Mizra.30 The idea that GDPs lack access to oxygen may arise from the fact that standard dental procedures typically do not necessitate the use of oxygen, as patients are usually conscious and breathing independently. Nevertheless, in scenarios involving sedation or anaesthesia, oxygen plays a crucial role in ensuring safety within dental practices. In practices where the former are not performed, GDPs may not see a need to procure oxygen cylinders and Ambu bags. It is therefore worth exploring further improvements in this aspect as it appears as if though preparedness is declining in SA.

Variability in drug availability

Among the examined drugs, aspirin was reported as the most available option (n=161, 44.7%) and tranexamic acid being the least available emergency drug, with no GDPs having access. This raises questions about the potential impact on the effective management of haemorrhagic emergencies within dental practice. Persistent bleeding increases the risk of haematoma formation and secondary infections, which can compromise the healing process.56 Infection risk rises when there is an open wound with continuous bleeding, potentially leading to localised or systemic infections.57 Uncontrolled bleeding can prolong the recovery period for the patient. Extended healing times may impact the patient's overall wellbeing and quality of life. Failure to manage post-operative haemorrhage adequately could have legal and ethical consequences for GDPs which could result in malpractice claims, damage to professional reputation and regulatory scrutiny. If results from this study are compared to Australia18,57-58, Germany10 and Great Britain6 it appears that South African GDPs are less prepared for emergency management.

Access barriers to emergency medical resources

GDPs face challenges in accessing emergency medical resources. These obstacles negatively influence the readiness of GDPs to manage emergencies effectively. Three-quarters of respondents have access to a nearby centre for referral (n=237, 65.8%). This suggests that the vast majority of GDPs may have a reliable avenue for transferring patients in critical situations, which is encouraging. This points to the importance of a collaborative approach between dental and medical facilities for comprehensive patient care. A nearby centre to manage emergencies can be pivotal in cases where the dental office might not have all the necessary resources. GDPs should, however, not rely solely on referring patients for urgent care, but should rather strive to enhance their skills to manage MEs when they do occur in the dental setting. It might be regarded as a luxury to have these services nearby; therefore GDPs should equip themselves to be competent.

Financial constraints and procurement challenges

A quarter of respondents (n=39, 29.8%) reported financial constraints as a primary factor contributing to the shortage of emergency resources in their practices. Addressing this issue is imperative to ensure adequate preparedness for MEs. Potential solutions include adjusting service tariffs to better accommodate emergency resource procurement and exploring alternative approaches to the acquisition of disposable medical supplies. One such approach could involve exchanging near-expiry drugs with emergency centres that utilise them more frequently, establishing collaborative agreements with pharmacies or implementing stricter inventory management protocols to monitor medication expiry dates within dental practices. Additionally, the perceived high cost of emergency training courses could be mitigated if increased attendance among GDPs leads to greater financial viability for course providers. It is essential to recognise that the consequences of an inadequately managed ME extend beyond the GDP, potentially affecting patients, staff and the broader professional community. The financial burden of emergency preparedness should therefore be weighed against the ethical responsibility of safeguarding human life. These findings underscore the direct relationship between access to emergency resources and the ability of GDPs to respond effectively to critical situations. Overcoming these barriers is essential to enhance patient safety and reinforce GDPs' confidence in managing MEs.

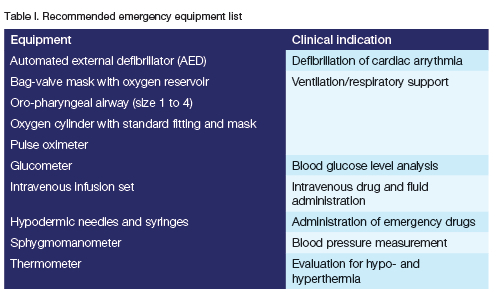

Given the complexity of potential emergencies in dental practice, there is a clear need for a comprehensive yet practical emergency drug and equipment list. This study identifies existing resources while integrating practitioner insights on essential emergency preparedness measures. However, recommendations must align with established literature. The emergency drug and equipment list was formulated based on a comprehensive literature review,2,6,13,59-67 assessing multiple published articles to identify a consistent pattern of essential drugs for inclusion. Additionally, qualitative responses were incorporated from the study findings, engaging in author discussions to determine the most relevant information for the dental setting to ensure a well-rounded and evidence-based selection. The inclusion or exclusion of specific items was determined based on their clinical relevance, accessibility and practicality in a dental setting, with emphasis on drugs essential for managing life-threatening emergencies while omitting those deemed redundant, impractical or outside the scope of routine dental practice. Table I presents a list of essential equipment, while Table II outlines an emergency drug list. Additionally, Figure III features a revised dental emergency flowchart designed to enhance preparedness in dental offices, ensuring effective management of medical emergencies until advanced medical support is available.

The revised dental emergency flowchart, updated in 2022, provides a structured guide for managing MEs in dental practice. Initially made available to members of SADA, it has since been made accessible online to non-members as well. This resource serves as a critical reference for dental professionals, ensuring they can effectively respond to emergency situations with clear, evidence-based protocols and is available from: https://www.sada.co.za/sites/default/files/content-files/Clinical%20Templates/Emergency%20Flow%20Chart%2010-10-2022.pdf

Study limitations

Participants' preparedness for MEs was self-assessed, introducing subjectivity and possibly not reflecting actual practices.

Questionnaire surveys are inherently limited and prone to reporting biases.

Uneven distribution of participants across regions and universities may skew results towards larger population centres and certain institutions.

Voluntary participation likely influenced the response rate.

CONCLUSION

This study assessed the preparedness of South African GDPs in managing MEs, focusing on emergency drug and equipment availability. Including practitioners from all provinces and sectors (private, public and academic), the findings revealed areas of concern:

• Lack of confidence and insecurity in the use of emergency drugs and equipment.

• Complacency and absence of incentive to procure emergency drugs and equipment.

• Unwillingness to procure ME drugs and equipment due to the cost of purchase, maintenance and potential expiration.

The data shows that despite positive attitudes, South African GDPs are not adequately prepared for MEs in dental settings, especially regarding emergency drugs and equipment use and its availability. Participants emphasised the need for an emergency drug and equipment list and an emergency flowchart to assist with ME management. This research highlights the importance of educational institutions, regulatory bodies and professional organisations in improving dental emergency care. Instituting a policy that mandates essential emergency drugs and equipment and adequate training is crucial. Further studies in SA are recommended to validate findings on emergency occurrences, practitioner confidence, knowledge and proficiency.

This study sets the stage for further research to enhance GDPs' competence for safer patient outcomes during MEs. It led to the development of an emergency drug and equipment list and a revised dental emergency flowchart in collaboration with SADA, the University of Pretoria and the University of the Witwatersrand.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Ms T Ruff (editorial support), Ms MME Gleeson (administrative assistance), Ms Peens (data preparation) as well as Adjunct Professor F Motara (University of the Witwatersrand) and Dr V Lalloo (University of Pretoria) for assistance in revising the dental emergency flowchart. Appreciation is also extended to Medpages International SA, SADA, Wright-Millners SA, NEXUS Dental Study Club, the Implant and Aesthetic Academy SA, OMERI Holdings and the dental schools at the University of Pretoria, the University of the Witwatersrand, the University of the Western Cape and Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University for their assistance in distributing the questionnaire.

DECLARATIONS

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial, commercial or any other associated interests to declare that represent a conflict of interest about the research undertaken and all other aspects related to the content of this paper.

Funding

The study was privately funded by the principal investigator and a research grant was received from the Department of Maxillo-Facial and Oral Surgery, School of Dentistry, Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Abbreviations

AED Automated external defibrillator

AHA American Heart Association

GDP General dental practitioner/dentist

GDPs General dental practitioners/dentists

KAPB Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices and Beliefs

ME Medical emergency

MEs Medical emergencies

SA South Africa

SADA The South African Dental Association

REFERENCES

1. Dental Council of New Zealand [Internet]. Practice standard for Medical Emergencies in Dental Practice 2005-2006. [updated 2008 January; amended by committee on 2014 Sep; cited 2023 Aug]. Available from: https://www.dcnz.org.nz [ Links ]

2. Dym H, Barzani G, Mohan N. Emergency Drugs for the Dental Office. Dent Clin North Am. 2016;60(2):287-94 [ Links ]

3. Prasad SD, Shashi K, Smita S, Prasad GP. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Basic Life Support among Postgraduate Dental residents and Dental Faculties at a Tertiary Hospital in Eastern Nepal. Journal of Advanced Medical and Dental Sciences Research. 2019;7(12):227-32 [ Links ]

4. Laurent F, Augustin P, Youngquist ST, Segal S. Medical emergencies in dental practice. Med Buccale Chir Buccale. 2014;20:3-12 [ Links ]

5. American Dental Association Council of Scientific Affairs. Office emergencies and emergency kits. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:364-5 [ Links ]

6. Atherton GJ, McCaul JA, Williams SA. Medical emergencies in general dental practice in Great Britain part 1: Their prevalence over a 10-year period. Br Dent J. 1999;186:72-9 [ Links ]

7. Atherton GJ, Pemberton MN, Thornhill MH. Medical emergencies: The experience of staff of a UK dental teaching hospital. Br Dent J. 2000;188(6):320-4 [ Links ]

8. Malamed SF. Medical emergencies in the dental surgery. Part 1: Preparation of the office and basic management. J Ir Dent Assoc. 2015;61(6):302-8 [ Links ]

9 Greenwood M. Medical emergencies in dental practice: 1. The drug box, equipment and general approach. Dent Update. 2009;36(4):202-4, 207-8, 211 [ Links ]

10. Muller MP, Hansel M, Stehr SN, Weber S, Koch T. A state-wide survey of medical emergency management in dental practices: Incidence of emergencies and training experience. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(5):296-300 [ Links ]

11. Smereka J, Aluchna M, Aluchna A, Szarpak L. Preparedness and attitudes towards medical emergencies in the dental office among polish dentists. Int Dent J. 2019;69(4):321-8 [ Links ]

12. Girdler NM, Smith DG. Prevalence of emergency events in British dental practice and emergency management skills of British dentists. Resuscitation. 1999;41(2):159-67 [ Links ]

13. Greenwood M, Meechan JG. General medicine and surgery for dental practitioners: Part 2. Medical emergencies in dental practice: The drug box, equipment and basic principles of management. Br Dent J. 2014;216(11):633-7 [ Links ]

14. Kumarswami S, Tiwari A, Parmar M, Shukla M, Bhatt A, Patel M. Evaluation of preparedness for medical emergencies at dental offices: A survey. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2015;5(1):47-51 [ Links ]

15. American Heart Association. The case for public access defibrillation (PAD) programs. [Accessed 17 August 2022]. Available from: www.americanheart.org/downloadable/heart/1053115415595padcase.pdf. Accessed: October 5, 2003 [ Links ]

16. Haas DA. Automated External Defibrillator Use In Dentistry. JCDA. 2007;73(4):289 [ Links ]

17. Perkins GD, Hulme J, Shore HR, Bion JF. Basic life support training for health care students. Resuscitation. 1999;41(1):19-23 [ Links ]

18. Chapman PJ. Medical emergencies in dental practice and choice of emergency drugs and equipment: A survey of Australian dentists. Aust Dent J. 1997;42(2):103-8 [ Links ]

19. Al Ghanam MA, Khawalde M. Preparedness of Dentists and Dental Clinics for Medical Emergencies in Jordan. Mater Sociomed. 2022;34(1):60-5 [ Links ]

20 Obata K, Naito H, Yakushiji H, Obara T, Ono K, Nojima T, et al. Incidence and characteristics of medical emergencies related to dental treatment: A retrospective single-center study. Acute Med Surg. 2021;8(1):651 [ Links ]

21. Vaughan M, Park A, Sholapurkar A, Esterman A. Medical emergencies in dental practice - management requirements and international practitioner proficiency. A scoping review. Aust Dent J. 2018;63(4):455-66 [ Links ]

22. Carvalho RM, Costa LR, Marcelo VC. Brazilian dental students' perceptions about medical emergencies: A qualitative exploratory study. J Dent Educ. 2008;72(11):1343-9. [ Links ]

23. Arsati F, Montalli VA, Florio FM, Ramacciato JC, da Cunha FL, Cecanho R, et al. Brazilian dentists' attitudes about medical emergencies during dental treatment. J Dent Educ. 2010;74(6):661-6 [ Links ]

24. Kharsan V Singh R, Madan R, Mahobia Y Agrawal A. The ability of oral & maxillofacial surgeons to perform basic life resuscitation in Chattisgarh. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(2):58-60 [ Links ]

25. Rosenberg M. Preparing for medical emergencies: The essential drugs and equipment for the dental office. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141 Suppl 1:14S-9S [ Links ]

26. Haas DA. Management of medical emergencies in the dental office: Conditions in each country, the extent of treatment by the dentist. Anesth Prog 2006;53:20-4 [ Links ]

27. Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa [Internet]. Training Pyramid/Annual Training Statistics. [Accessed 24 August 2022]. Available from https://resus.co.za/subpages/RCSA_Information/Resources/Training_Pyramid.html [ Links ]

28. Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa [Internet]. Algorithms. [Accessed 24 August 2022]. Available from: https://resus.co.za/subpages/RCSA_Information/Resources/Algorithms.html [ Links ]

29. South African Dental Association [Internet]. Dental Emergency Flow Chart. 2022. [Accessed 19 September 2022]. Available from: https://www.sada.co.za/sites/default/files/contentfiles/Clinical%20Templates/Emergency%20Flow%20Chart%2010-10-2022.pdf [ Links ]

30. Owen CP, Mizra N. Medical emergencies in dental practices in South Africa. SADJ August. 2015;70(7):300-3 [ Links ]

31. Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Browner WS, Grady DG, Newman TB. Designing Clinical Research. 3rd ed. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2007:65-94 [ Links ]

32. Merchant RM, Topjian AA, Panchal AR, Cheng A, Aziz K, Berg KM, et al. Part 1: Part 1: Executive Summary: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2020;142(16_suppl_2):S337-S57 [ Links ]

33. Magid DJ, Aziz K, Cheng A, Hazinski MF, Hoover AV, Mahgoub M, et al. Part 2: Part 2: Evidence Evaluation and Guidelines Development: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2020;142(16_suppl_2):S358-S65. [ Links ]

34. Panchal AR, Bartos JA, Cabanas JG, Donnino MW, Drennan IR, Hirsch KG, et al. Part 3: Part 3: Adult Basic and Advanced Life Support: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2020; 142(16_suppl_2):S366-S468 [ Links ]

35. Topjian AA, Raymond TT, Atkins D, Chan M, Duff JP, Joyner BL, Jr, et al. Part 4: Pediatric Basic and Advanced Life Support: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2020;142(16_suppl_2):S469-S523 [ Links ]

36. Aziz K, Lee HC, Escobedo MB, Hoover AV, Kamath-Rayne BD, Kapadia VS, et al. Part 5: Neonatal Resuscitation: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2020; 142(16_suppl_2):S524-S50 [ Links ]

37. Berg KM, Cheng A, Panchal AR, Topjian AA, Aziz K, Bhanji F, et al. Part 7: Systems of Care: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2020;142(16_suppl_2):S580-S604 [ Links ]

38. Cheng A, Magid DJ, Auerbach M, Bhanji F, Bigham BL, Blewer AL, et al. Part 6: Resuscitation Education Science: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2020;142(16_suppl_2):S551-S79 [ Links ]

39. Braun V, Clarke V Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology. 2006;3(2):77-101 [ Links ]

40. Narayan DP, Biradar SV, Reddy MT, Sujatha BK. Assessment of knowledge and attitude about basic life support among dental interns and postgraduate students in Bangalore city, India. World J Emerg Med. 2015;6(2):118-22 [ Links ]

41. Doshi D, Baldava P, Reddy S, Singh R. Self-reported knowledge and practice of American Heart Association 2007 guidelines for prevention of infective endocarditis: A survey among dentists in Hyderabad city, India. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2011;9(4):347-51 [ Links ]

42. Nogami K, Taniguchi S, Ichiyama T. Rapid Deterioration of Basic Life Support Skills in Dentists With Basic Life Support Healthcare Provider. Anesth Prog. 2016;63(2):62- 6 [ Links ]

43. Jamalpour MR, Asadi HK, Zarei K. Basic life support knowledge and skills of Iranian general dental practitioners to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Niger Med J. 2015;56(2):148-52 [ Links ]

44. Al-Iryani GM, Ali FM, Alnami NH, Almashhur SK, Adawi MA, Tairy AA. Knowledge and Preparedness of Dental Practitioners on Management of Medical Emergencies in Jazan Province. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018 Feb;14(6(2)):402-5 [ Links ]

45. Alkandari SA, Alyahya L, Abdulwahab M. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation knowledge and attitude among general dentists in Kuwait. World J Emerg Med. 2017;8(1):19-24 [ Links ]

46. I rfan B, Zahid I, Khan MS, Khan OAA, Zaidi S, Awan S, et al. Current state of knowledge of basic life support in health professionals of the largest city in Pakistan: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):865 [ Links ]

47. Broadbent JM, Thomson WM. The readiness of New Zealand general dental practitioners for medical emergencies. N Z Dent J. 2001;97(429):82-6 [ Links ]

48. Arsati F, Montalli VA, Florio FM, Ramacciato JC, da Cunha FL, Cecanho R, et al. Brazilian dentists' attitudes about medical emergencies during dental treatment. J Dent Educ. 2010;74(6):661-6 [ Links ]

49. Krishnamurthy M, Venugopal NK, Leburu A, Kasiswamy Elangovan S, Nehrudhas P. Knowledge and attitude toward anaphylaxis during local anesthesia among dental practitioners in Chennai - a cross-sectional study. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2018;10:117-21 [ Links ]

50. Marks LA, Van Parys C, Coppens M, Herregods L. Awareness of dental practitioners to cope with a medical emergency: A survey in Belgium. Int Dent J. 2013;63(6):312-6 [ Links ]

51. Al-Sebaei MO, Jan AM. A survey to assess knowledge, practice, and attitude of dentists in the western region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2016;37(4):440-5 [ Links ]

52. Gonzaga HF, Buso L, Jorge MA, Gonzaga LH, Chaves MD, Almeida OP. Evaluation of knowledge and experience of dentists of Sao Paulo State, Brazil about cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Braz Dent J. 2003;14(3):220-2 [ Links ]

53. Yang F, Zheng C, Zhu T, Zhang D. Assessment of life support skills of resident dentists using OSCE: cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):710 [ Links ]

54. Khami MR, Yazdani R, Afzalimoghaddam M, Razeghi S, Moscowchi A. Medical emergency management among Iranian dentists. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2014;15(6):693-8 [ Links ]

55. Bhayat A, Chikte U. The changing demographic profile of dentists and dental specialists in South Africa: 2002-2015. Int Dent J. 2018;68(2):91-6 [ Links ]

56. Matocha DL. Postsurgical complications. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2000 Aug;18(3):549-64 [ Links ]

57. Chapman S, Jackson KA. Understanding the A's and B's of respiratory care. Nursing. 1995;25(9):32PP-RR. 74 [ Links ]

58. Chapman PJ. An overview of drugs and ancillary equipment for the dentist's emergency kit. Aust Dent J. 2003;48(2):130-3 [ Links ]

59. Dym H. Preparing the dental office for medical emergencies. Dent Clin North Am. 2008;52(3):605-8 [ Links ]

60. Rosenfeld J, Dym H. Emergency Drugs for the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon Office. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2022;34(1):1-7 [ Links ]

61. Jevon P. Medical emergencies in the dental practice poster: Revised and updated. Br Dent J. 2020;229(2):97-104 [ Links ]

62. Kloeck WGJ. A Guide to the Management of Common Medical Emergencies in Adults. 12th ed. Academy of Advanced Life Support. 2020:1-188 [ Links ]

63. Haas DA. Management of medical emergencies in the dental office: Conditions in each country, the extent of treatment by the dentist. Anesth Prog. 2006; 53(1):20-4 [ Links ]

64. Basic Life Support Provider Manual. International English Edition. American Heart Association. 2020:1-110 [ Links ]

65. Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support Provider Manual. International English Edition. American Heart Association. 2020:1-202 [ Links ]

66. Pediatric Advanced Life Support Provider Manual. International English Edition. American Heart Association. American Academy of Pediatrics. 2020:1-330 [ Links ]

67. Advanced Trauma Life Support. Student Course Manual. 10th ed. American College of Surgeons. 2018:1-391 [ Links ]

68. Elangovan N, Sundaravel E. Method of preparing a document for survey instrument validation by experts. Elsevier BV. 2021(8) [ Links ]

69. Zarins B. Are Validated Questionnaires Valid? Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. Wolters Kluer. 2005;87:1671 [ Links ]

70. Smith AK, Ayanian JZ, Covinsky KE, Landon BE, McCarthy EP, Wee CC, et al. Conducting High-Value Secondary Dataset Analysis: An Introductory Guide and Resources. Journal of General Internal Medicine. Springer Science and Business Media. 2011;26(8):920 [ Links ]

71. Prince M. Measurement validity in cross-cultural comparative research. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale. Cambridge University Press; 2008;17(3):211 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Steve Swanepoel

Tel: +27(17) 712-5940/Cell: +27(82) 828 3650

Email: drsteveswanepoel@oralsurgery.org.za

Author's contribution

1. Steve Swanepoel - principal author, study conceptualisation and design, literature review, intellectual content, dental emergency flowchart review, participant recruitment, funding, data- and statistical analysis, manuscript layout, preparation and write-up, proofreading, editing and review. Contribution: 100%

2. Karl-Heinz Merbold - second author, intellectual content, participant recruitment, manuscript layout, preparation and write-up, proofreading, editing and review. Contribution: 100%

3. Tinesha Parbhoo - third author, dental emergency flowchart conceptualisation, design and review. Contribution: Manuscript review.