Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Historia

On-line version ISSN 2309-8392Print version ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.64 n.2 Durban Nov. 2019

https://doi.org/10.17159/2309-8392/2019/v64n2a3

ARTICLES

"A hygienic Native township shall be developed": The founding and development of Batho as Bloemfontein's "model location" (c. 1918-1939)

D. du BruynI,*; M. OelofseII,*

IPrincipal museum scientist at the National Museum in Bloemfontein and a research fellow of the History Department at the University of the Free State, Bloemfontein

IILecturer in the History Department at the University of the Free State

ABSTRACT

Batho, Bloemfontein's oldest existing historically black township or "location", celebrated its centennial in 2018. This "model location" was established in 1918 by the Municipality of Bloemfontein after it decided to demolish the old Waaihoek location. The model location ideology, partly rooted in the image of the Orange Free State "model republic" of the late 1800s, must be seen within the context of the discriminatory segregationist policies of the 1920s and 1930s. The main reasons for Batho's founding and Waaihoek's demolition were: i) prejudiced and troubled race relations and racial attitudes; ii) Waaihoek's close proximity to white Bloemfontein; iii) the growing urbanisation of black and coloured people; iv) the Spanish Influenza epidemic; and v) the building of a new power station for Bloemfontein. Batho became nationally renowned as a model location and an example for others to follow due, in part, to the municipality's unique housing scheme, namely the Bloemfontein system. The model location ideology influenced Batho's general layout, size of individual plots, provisioning of public amenities, sound financial administration and limited participative governance in the form of advisory boards. The main thesis is that the municipality's ideal of a model location was not simply a theoretical and ideological construct, but that it was also materialised in practice.

Keywords: Batho; Bloemfontein; Waaihoek; location; "model location"; Bloemfontein system; plot size.

OPSOMMING

In 2018 het Batho, Bloemfontein se oudste bestaande histories-swart township of "lokasie", sy eeufees gevier. Hierdie "modellokasie" is in 1918 deur die munisipaliteit van Bloemfontein gestig nadat besluit is om die ou Waaihoek-lokasie te sloop. Die modellokasie-ideologie, wat deels uit die tyd van die "model republiek" Oranje-Vrystaat van die laat 1800's dateer, moet binne die konteks van die diskriminerende segregasionistiese beleide van die 1920's en 1930's beskou word. Die hoofredes vir Batho se stigting en Waaihoek se sloping was: i) bevooroordeelde en vertroebelde rasseverhoudinge en rassehoudinge; ii) Waaihoek se nabyheid aan wit Bloemfontein; iii) die groeiende verstedeliking van swart en bruin mense; iv) die Spaanse griepepidemie; en v) die bou van 'n nuwe kragstasie vir Bloemfontein. Batho het nasionaal as 'n modellokasie bekend geword en as 'n voorbeeld vir ander lokasies gedien, deels vanweë die munisipaliteit se unieke behuisingskema, naamlik die Bloemfontein-sisteem. Die modellokasie-ideologie het Batho se algemene uitleg, grootte van individuele standplase, voorsiening van openbare geriewe, behoorlike finansiële administrasie en beperkte deelnemende bestuur in die vorm van adviesrade, beïnvloed. Die hoofargument is dat die munisipaliteit se ideaal van 'n modellokasie nie bloot 'n teoretiese en ideologiese konstruk was nie, maar ook in die praktyk gerealiseer het.

Sleutelwoorde: Baaho; Bloemfontein; Waaihoek; lokasie; "modellokasie"; Bloemfontein-sisteem; standplaas-grootte.

Introduction

The history of urban townships1 and "locations"2 and the forces that underpin their foundation and development is an important theme of South African urban historiography. Recent research conducted by Marc Epprecht,3 Karina Sevenhuysen4and Harri Mäki,5 to name but a few, may be mentioned in this regard. Older studies conducted by other researchers, such as Maynard Swanson6 and Paul Maylam,7remain equally significant. The study of the so-called "model location" phenomenon of the 1920s and 1930s and the reasons for establishing class-differentiated and racially-segregated urban spaces is still an important issue despite the attention they have already received by historians. In these works, a number of "model native villages" and "model locations", particularly those established in the Union of South Africa's major urban centres, have been investigated as case studies. In most instances, it was concluded that the municipal ideal of the model native village only materialised in some respects due to insufficient funding, although there were other salient reasons in particular contexts. Langa8 (outside Cape Town), Sobantu9(Pietermaritzburg) and Lamontville10 (Durban) - all established during the 1920s and 1930s - may be mentioned in this regard.

In 1918, the Municipality of Bloemfontein11 (hereafter also referred to as the municipality) established the city's own model location, namely Batho.12 In 2018, Batho, Bloemfontein's oldest existing13 (historically black-designated) township, celebrated its centennial. Based on extensive research conducted on the founding and subsequent development of Batho, the main thesis of this article is that the Bloemfontein Municipality's idea of a model location was not merely a theoretical and ideological construct. Rather, and due to the efforts made by municipal officials and the implementation of a unique housing scheme, known as the Bloemfontein system, the new location was realised as a "model location" in practical terms as well.

The model location ideology should be seen in the context of the racist and discriminatory segregationist policies enforced by South African local authorities during the 1920s and 1930s. Thus, the intention of this article is not to glorify Batho as a model location but rather to explore its significance within the context of South African town planning and the factors that influenced it. The establishment of Batho is important because at the time of its founding, it was reportedly the first location to be officially termed a model location and referred to as such in official records.

Research questions that will be asked include, inter alia, the following: What were the reasons and motivations for the founding of Batho in 1918?; What practical measures and steps were taken by the municipality to develop Batho as a model location during the 1920s and 1930s?; What are the historical roots of the model location ideology as it was applied to Batho?; Why was Batho considered an example or even a blueprint for other locations in the Union?; and was Batho considered a model location only by municipal officials and the Union government, or by others, such as Batho's residents, as well? It is argued that Batho was "exemplary" in the social and political context of the period under discussion, namely 1918 to 1939, particularly when compared to the dismal state of other locations at that time.

Background

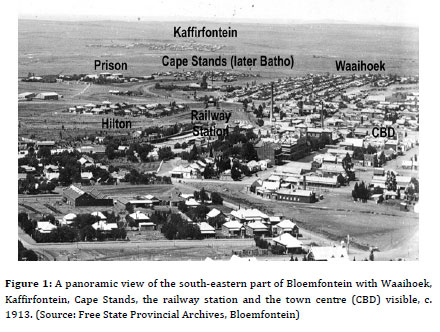

Batho and its founding history cannot be viewed in isolation from that of Bloemfontein's first and oldest main location, namely Waaihoek14 and, to an extent, the other smaller, older locations, namely Kaffirfontein,15 Cape Stands, and the No. 3 Location16 (Figure 1 below). The strong historical link which existed between Batho and these four locations derives from the fact that Batho's original residents all hailed from Waaihoek, Kaffirfontein, Cape Stands and the No. 3 Location.

Batho's original residents were descendants of the San,17 Khoekhoe18 and emancipated slaves, such as the Griqua, Korana and Bastards. Original residents were also Bantu-speaking,19 specifically Sotho-Tswana and their descendants, who, because of migration, had found themselves in the area between the Orange and Vaal Rivers since the early 1800s. Small groups of people widely known as "coloureds"20and "blacks",21 respectively, settled in the vicinity of the farm, Bloem Fontein (sic), where they came into contact with a group of people of European orign, namely white travellers and trekboers. Since Bloemfontein's founding in 1846, people of colour have lived in small, scattered settlements in the town's vicinity.22

Initially, Bloemfontein's black and coloured residents were kept at a distance by the whites. It was only in the early 1860s that their permanence, albeit with the status of servants, was accepted when the Bloemfontein Town Council concentrated them in three ethnically-based locations: Kaffirfontein for Fingoes23 and Barolong (Tswana), the Schut Kraal Locatie for Khoekhoe and Bastards and, finally, Waaihoek, which was situated near Fort Hill,24 for the other black and coloured people. In 1872, the council decided to demolish the Schut Kraal Locatie and resettled the residents in Waaihoek. By then, Waaihoek had become Bloemfontein's main location and, in addition to the black residents, the occupants were described as "Hottentots, Griquas and Cape boys [sic] and women".25 The other location was Kaffirfontein, which was smaller and situated south of Waaihoek near the Kaffirfontein Spruit.26

For most of the nineteenth century, Bloemfontein's white population exceeded that of the black and coloured people. It was only in 1895 that the number of blacks and coloureds combined exceeded that of the whites, mainly as a result of urbanisation and population growth.27 This demographic trend had a profound impact on town planning in Bloemfontein. The growing racial imbalance caused much anxiety among Bloemfontein's whites and, to quote a source on conditions in the Orange Free State soon after the Anglo-Boer War (hereafter also referred to as the war), they found reassurance in the idea that "the natives have their defined areas".28Similar racial sentiments held sway before the war.29

"Segregation is essential and moral": Reasons for Batho's founding and Waaihoek's demolition

In his annual report for 1885, the mayor of Bloemfontein, Mr S. Goddard,30 reported that "the general condition of things at the Locations continues to be fairly satisfactory".31 Although Mayor Goddard referred to "locations" he, in actual fact, meant Waaihoek. Waaihoek was also described in positive terms by Reverend Gabriel David, a local Anglican priest and one of Waaihoek's most well-known residents.32 In a report of the Anglican Church's missionary activities for the year 1885, David wrote that "our people in 1871 used to live in round huts covered with rags, They [sic] now live in square houses thatched with grass, very clean indeed, their location is called Waia Hoek [sic]".33 To improve the general orderliness in Waaihoek, a plan for the rearrangement and rebuilding of some of its houses was implemented in 1892. In terms of this plan, which enforced specific building rules, all houses were to be built in "proper rows and streets"34 so that the houses stood in a straight line next to one another and were in line with the sidewalk and street.35 The municipality's insistence on "proper" orderliness should be viewed within the larger context of British urban planning trends which influenced town planning in South Africa. In this regard, the philosophies of the British town planning visionary and father of the Garden City Movement, Ebenezer Howard, should be mentioned. Howard advocated orderly urban planning and the idea of the "garden city"36 consisting of "garden suburb[s]".37

Viewed from the municipality's perspective, the new building rules not only improved the quality of the houses but also enhanced the appearance of the plots or stands. The average Waaihoek plot was square and measured 50 x 50 feet.38According to the then mayor, Dr B.O. Kellner,39 the results achieved by means of the building rules were so impressive that he was convinced that Waaihoek "will in another year's time become a model location".40 Kellner's opinion, specifically his description of Waaihoek as a potential "model location", is significant since it indicates that the idea of the model location was no novelty when Batho was described as such more than twenty years later. However, references to Waaihoek as a model location, partly rooted in the "model republic" and "model city" concepts discussed later, should be seen in context because the general living conditions in Waaihoek (not to mention the other locations) were not nearly comparable to those in the better parts of the so-called white "Town". More importantly, Kellner and other mayors, such as Mr S.P.J. Sowden's,41 ambition to see Waaihoek becoming a model location never materialised, mainly because of serious overcrowding and its side effects.42

Since Waaihoek was conveniently located close to the (white) "Town" and the employment opportunities offered there by government departments, the municipality, businesses and white households, it filled up rather quickly. The annual report of Bloemfontein's mayor for the year 1897 reported that the council faced a dilemma: all 537 available plots in Waaihoek had been occupied, with virtually no space left for expansion. While building sites were no longer available, increasing numbers of newcomers applied to live there. According to the vice-mayor, Mr C.G. Fichardt, the council reached the point where it had to decide whether Waaihoek, being so near to the town, was not already large enough. Either new applicants were to be provided with plots in distant Kaffirfontein or, in the words of Fichardt, they had to be accommodated in "a third location somewhat nearer".43 In practical terms, this meant a new location situated closer to town than Kaffirfontein but not as near the town as Waaihoek.

The fact that this "third location somewhat nearer", that is Batho, was only established in 1918 meant that the council's decision to lay out a new location and demolish Waaihoek was not taken overnight. A number of factors, some of which had been in the making for some time, contributed to the council's decision. Although the cro ded conditions in Waaihoek ere an important driving force in the municipality's quest to develop a new location, there were also other factors involved, namely race relations, Waaihoek's proximity to white Bloemfontein, the growing urbanisation of black and coloured people, the Spanish Influenza epidemic and, finally, the construction of a new power station for Bloemfontein.

Race relations and racial attitudes

To understand the early history of Batho and, in fact, the history of all of Bloemfontein's historically-designated black areas, the white residents' racial attitudes must be understood. In Bloemfontein, we need to qualify the term "white residents" since the racial attitudes of English-speaking residents were somewhat less rigid and harsh than those of Afrikaans-speakers.44 Due to their relatively less rigid stance, some English-speaking residents and the predominantly English-speaking council and municipal officials were often described as "progressive".45Officially, however, the council and the majority of Bloemfontein's residents maintained that people of colour, whether they were born in Bloemfontein or not, were not true citizens of the town but were merely "servants of the townspeople".46Thus, people of colour were only tolerated in the locations as long as they were useful to the whites.47

Racial prejudice was not limited to informal attitudes. They also found their way into rules, regulations, policies and legislation. Although mostly informally enforced since Bloe fontein's foundation, the idea of territorial segregation increasingly became the guiding principle which informed all racial policies, notably on municipal level.48 During a public meeting with Waaihoek's residents on the eve of Batho's establishment in 1918, Councillor A.G. Barlow explained this ideology in simple and stark terms: "It was not good that the Whites and Blacks should live so close."49 Barlow's opinion was not unusual in the context of the Union government's promotion of racialised territorial segregation for all new municipal town planning schemes.50

By the mid-1920s, the council had introduced a "definite native policy"51 which conformed to the "general segregation principles as laid down by the previous and present Government",52 notably the principles contained in the Natives (Urban Areas) Act of 1923, to be discussed later. Thus, the founding of Batho must be viewed against the backdrop of the Union government's segregation principles as implemented on municipal level. Since 1910 these principles had become more pronounced and defined, and affected all aspects of the lives of the location residents, including their domestic environment. For the average location resident, the practical implication of these general segregation principles meant, in the words of journalist, Mr R.V. Selope-Thema, the policy of "keeping the Kaffir in his place".53

Waaihoek's proximity to white Bloemfontein

Another important reason for Batho's establishment and Waaihoek's demolition was Waaihoek's close proximity to hite Bloemfontein. In practical terms, the establishment of Batho, according to the mentioned "general segregation principles", had a great deal to do with "the position of the location in relation to the European portion of the city",54 to quote Mayor L.W. Deane.55 Since Waaihoek came into being during the second half of the 1800s and grew exponentially into Bloemfontein's main location, the initial open piece of veld between Waaihoek and Bloemfontein's main area of commerce, namely the market square (later Hoffman Square) and the businesses situated around it, gradually disappeared. Furthermore, in the vicinity of Rhodes Avenue, Fort Street, Zulu Street and Harvey Road, the initial racial divide became blurred since working-class and poor whites lived in close proximity to the black and coloured residents. According to The Friend,56in some parts of Waaihoek coloured and white residents lived on opposite sides of the same street. For most of Bloemfontein's white citizens, this became problematic since seemingly they, like the municipality, had accepted the idea that "segregation is essential and moral".57

Although various efforts were made by the municipality and Waaihoek's residents to improve conditions in the location, it seemed impossible to remedy the squalor caused by overcrowding and inadequate sanitation. In his testimony before the Influenza Epidemic Commission (1918), Henry Selby Msimang, then a prominent Waaihoek resident and editor of the newspaper, Morumioa-Inxusa,58referred to the congested conditions in Waaihoek which were caused by overcrowding and too many people co-habiting in smal houses and other substandard structures. These conditions not only posed a threat to the health of Waaihoek's residents but indirectly also to the health of Bloemfontein's white residents - a fact not lost on the municipality and the white electorate.59 In this regard, reference may be made to the so-called "sanitation syndrome", a concept first stressed by Maynard Swanson. Swanson's theory explains urban segregation in terms of the perceived threat black people and their insanitary living quarters posed to the health of whites and the authorities' use of medical terms to justify residential segregation.60

Added to Waaihoek's slum conditions were other socio-economic issues which ranged from minimum wage61 demands to the brewing of traditional beer. Discontent about the council's strict sorghum beer regulations triggered the Waaihoek riots of 19 April 1925, when black residents and a commando of white men armed with picks and axes clashed at Waaihoek's entrance in Harvey Road.62 This violent incident, which happened on white Bloemfontein's doorstep, caused such alarm that it prompted the council to deal with the resettlement of Waaihoek's residents as a matter of urgency. The Government Riots Commission's recommendation63 that Waaihoek's residents should be "transferred to the east side of the railway line to the south as soon as possible",64 gave further impetus to plans to establish a new location further away from Bloemfontein "Town".65

The urbanisation of black and coloured people

At a conference on "Native Affairs"66 held in Johannesburg in 1924, the well-known Senator J.D. Rheinallt Jones explained the urbanisation phenomenon in South Africa as follows: "... the Poor Whites and Natives drifted to the towns, largely because the conditions of life and labour on the land were unsatisfactory."67 The desperate conditions of life and labour were the push factors, while the promise of a better life and possible employment in the towns and cities were the pull factors.68 This had been the case in South Africa and, most notably, in the Orange Free State,69 before and after the war. Between 1904 and 1921 the number of black people in South Africa's urban areas increased by 71,4%. In the case of black and coloured people, the economic devastation caused by the war, the far-reaching implications of the Natives' Land Act (No. 27 of 1913) and, finally, the impact of the economic depression of the late 1920s and early 1930s, were critical push factors. In most cases, black and coloured families had no choice but to migrate to towns and cities because in terms of the Land Act, they had no claim to land outside the so-called "reserves" and the "scheduled native areas", namely the locations.70

In the case of Bloemfontein, migrants settled mostly in Waaihoek, the capital's main location and the obvious choice of residence for the new arrivals. Who exactly were these migrants who the Bloemfontein Municipality's superintendent of locations referred to as "people from outside"?71 In 1919, the superintendent reported that apart from Barolong "trekking in with their families", people were "also coming in from the [Cape] Colony".72 The migrants were black and coloured people, among them Sotho, Tswana and Barolong from Thaba Nchu, as well as members of other indigenous groups and their descendants (Griqua, Korana and Bastards), some of whom were from the Cape Colony. Others also came from the various mission stations established in the southern and eastern Orange Free State during the early nineteenth century. By the turn of the century, most of these stations had ceased to exist and the black and coloured brethren either migrated to the nearest farms or towns or, as was the case for many, to Bloemfontein.73

The Spanish Influenza epidemic

The demolition of Waaihoek became a matter of urgency for the municipality when Bloemfontein, like the rest of South Africa, was hit by the "new and fashionable disease known as 'Spanish Influenza'"74 in early October 1918. During the course of six weeks in October and November 1918, the worldwide pandemic of the Spanish Influenza,75 also known as the Spanish Flu, affected Bloemfontein when approximately half of the city's residents contracted the disease.76 Although the whites were hit hard, the Bloemfontein-based daily newspaper, The Friend, informed its readers shortly after the outbreak of the disease that a large number of cases had been reported in the location.77 By the end of November 1918, when the pandemic had run its course, 400 whites (out of a total of 15 000) and 900 blacks and coloureds (out of a total of 16 000) had succumbed to the disease.78

The municipality's Housing and Public Health Committees launched an investigation into the causes of the epidemic and released a joint memorandum and report79 with recommendations. In the memorandum, Councillor Barlow, chairman of the Housing Committee, and Mr W.M. Barnes, chairman of the Public Health Committee, noted that the mortality rate was most severe in the overcrowded parts of the city. It was found that one of the main causes of the casualties was "bad housing, overcrowding and dirt".80

In addition to the municipal committees' investigation, a national commission of enquiry was appointed to investigate the influenza epidemic. At the Influenza Epidemic Commission's hearings held in Bloemfontein on 10 and 11 January 1919,81Msimang bluntly informed the commissioners that Bloemfontein's locations were too congested. According to him, Waaihoek's plots "sometimes had more than one building on, [and] most of the buildings had not [sic] sufficient ventilation".82Msimang also testified that because location residents had no right of ownership, they were discouraged from not only building decent houses but also from maintaining and improving the grounds around the houses.83

In his testimony, the mayor, Mr D.A. Thomson,84 made an important revelation. He said that the council had considered a new housing scheme before the epidemic, but "the disease had shown that such a scheme was urgently needed to procure the betterment of health and conditions of the citizens".85 At face value, it appears as if the citizens whose health and conditions were at stake were Bloemfontein's whites, especially if the mentioned sanitation syndrome theory is applied here. However, it only became clear for which "citizens" the scheme was meant when Councillor Barlow informed the commission that the municipality "had a scheme on hand for a new location to house 15 000 natives".86 Barlow's mention of a new location was one of the earliest public references to Batho. Apart from amenities, such as a town hall, a clinic, a library, swimming baths and recreation grounds, Barlow said that 'large grounds",87 in other words, sizeable plots, were also provided for in the plan.88 Only later it became evident that the bigger plots were meant to accommodate not only bigger houses but gardens and backyards as well.

Bloemfontein's new power station

A fifth reason for the establishment of Batho and subsequent demolition of Waaihoek was the council's argument that the area of Waaihoek closest to the town, specifically the area where the iconic St Patrick's Anglican Church stood, was needed as a site for the erection of Bloemfontein's new power station. While the decision to build Bloemfontein's new power station on a piece of land occupied by Waaihoek had been taken before Batho was founded, it was only in 1924 that more than 200 houses in this area, referred to as the "condemned area",89 were identified for demolition. These houses stood on the site required for the new power station.90 The first phase of the main power facility was opened on 24 March 1927, barely two years after the first sod had been turned in March 1925.91 Although initially spared, the St Patrick's Church was demolished in 1954 to make room for cooling towers.92

"A hygienic Native township shall be developed": The founding of Batho and the demolition of Waaihoek

In the mayor's annual report for 1919-1920, it was reported that according to the "universally accepted principle of segregation", the council had decided that:

... the South-Eastern quarter of the town, bounded roughly by the Natal [railway] Line and the Cape Line shall be the area where a hygienic Native township shall be developed with a higher standard of housing than that usually associated with locations.93

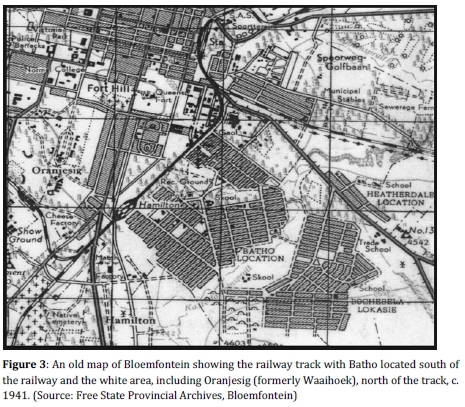

Mayor Thomson's statement, which officially mentions Batho's founding, contains important information. The principle of segregation, discussed earlier, referred to the segregationist urban planning principles,94 endorsed and enforced by the then Union government. These principles were later contained and described in detail in the Natives (Urban Areas) Act of 1923. Essentially, this Act entrenched the legal segregation of residential areas in South African towns and cities on the basis of race. The "South-Eastern quarter of the town" referred to the area east of the Johannesburg/Cape Town railway line which, at that time, was still vacant land except for the relatively small area occupied by Cape Stands (Figure 2).

Since the council "moved all the Africans across the railway",95 to quote Councillor Barlow, the railway track had become the physical barrier between black and white Bloemfontein. This meant that proper residential differentiation and, eventually, segregation came into being as a matter of principle: the whites were concentrated west of the railway and the blacks and coloureds east of the railway in Batho and Heatherdale, respectively96 (Figure 3). Thus, the railway served as a buffer strip or cordon sanitaire, a practice of residential demarcation which had become a key feature of segregationist town planning not only in Bloemfontein but elsewhere as well.97

The relocation of Waaihoek's residents to Batho and the reclamation of Waaihoek, which began in earnest in 1918, had material implications for the residents. It meant that they had to leave their homes and move from Waaihoek - the location in which many of them had been born and called home for almost seventy years - to a new home in a new location. The council's intention was to eventually reclaim the entire Waaihoek location by purchasing houses in specific demarcated "condemned areas",98 and to then have the areas cleared by demolishing all houses and structures. Waaihoek was designated to become a working-class white area known as Oranjesig (Figure 3). It is important to note that the demolition and reclamation of Waaihoek was a gradual process which commenced in 1918, the year in which Batho was founded, and implemented over a period of twenty years. Officially, Waaihoek's last houses were demolished in 1941.99

It seems as though most of Waaihoek's residents were willing to move to Batho, considering the prospect of a better laid-out location with better housing and amenities. As early as May 1919, Barlow, who took personal credit for having initiated the relocation of Waaihoek's residents to Batho,100 reported in a council meeting that Waaihoek "was slowly vanishing at present, and people were going over to the big location on their own account".101 Although Waaihoek's residents did not have a choice on whether they wanted to move or not, the fact that they reportedly moved there "on their own account" may be credited to the council's pragmatic handling of the resettlement process.102 Compared to the way in which forced removals were later handled in other towns and cities, especially in the 1950s (for example, Sophiatown, Johannesburg) and 1960s (for example, District Six, Cape Town), the move from Waaihoek to Batho was different. One of the reasons for the gradual and lengthy resettlement process was the cost involved - a factor which severely compromised the development of other model native villages.103Nonetheless, and even though Bloemfontein's council was notorious among local black residents for its strict enforcement of segregationist and social control laws, its relatively sympathetic approach to the Batho resettlement project was remarkable and contributed to Batho becoming a model location.104

"Assisted by the Council": The Bloemfontein system

Apart from the council's pragmatic approach, there was another important reason for the Waaihoek residents' initial enthusiasm for Batho and their apparent willingness to move and live there. Certainly, the overcrowding and slum conditions in Waaihoek were a significant 'push' factor but there also happened to be an important 'pull' factor, namely the unique housing scheme implemented in Batho known as the Bloemfontein system.105 This housing scheme, for which Bloemfontein became renowned nationally, must be viewed against the historical background of early twentieth-century black housing in South Africa. During the first two decades after Union, a haphazard approach towards black housing was followed in the majority of the country's urban centres. In the absence of a coherent national housing policy, neither the municipalities nor the provincial authorities considered black housing their responsibility. The provisioning of housing for their employees was entirely the prerogative of the employers of black labour. In this context, "employees" refers to the semi-permanent and permanent "native town-dwellers[s]",106 who became a permanent feature of almost all South African towns and cities at the time.107

Apart from the growing mining industry and the migrant labour system, rapid industrialisation also attracted sizeable numbers of black labourers to the Union's urban centres. The employers, who were mostly factory owners, did not consider the provisioning of housing for their employees an urgent matter. Needless to say, the lack of adequate housing for the thousands of newcomers had turned most urban locations into overcrowded slums. Well-known African academic, Dr D.D.T. Jabavu, described the "squalid surroundings" that were typical of most urban locations of the late 1910s, as follows: ". conveniences are distant, sometimes non-existent; water is hard to get; light is little; sanitation bad; while there are no common laundry buildings, no gardens, no amusement halls or clubs."108 Initially, the Union government ignored this growing urban housing crisis but the potential threat posed by unhygienic conditions to the white residential areas prompted the authorities to act. Commissions of enquiry were appointed to investigate the state of black living conditions in urban areas, notably the South African Native Affairs Commission (1903-1905) and the Tuberculosis Commission (1914).109 The findings of these commissions, as well as the consequences of the Spanish Influenza epidemic outlined above, led to the tabling of the Public Health Act (No. 36 of 1919).110

Among other things, the Public Health Act assigned the control of health conditions in urban areas to local authorities. Although this Act had many shortcomings, it laid the foundation for the significant Housing Act (No. 35 of 1920).111 This Act was the Union government's first deliberate effort to address the black housing question, notably by providing financial assistance to local authorities which enabled them to finance black housing schemes. It is important to note that many of the Housing Act's regulations were based on the practice followed in Bloemfontein, and specifically, the council's innovative "scheme of financial assistance to citizens to build their own homes".112 This scheme of financial assistance, which was considered a blueprint, refers to the assisted housing scheme which characterised the Bloemfontein system.113 The other prominent housing scheme comparable to the Bloemfontein system was known as the Johannesburg system. While the Johannesburg system allowed for the building of houses for location residents by the municipality and the letting of such houses to them, the Bloemfontein system allowed for residents to build their own houses with the municipality's assistance.114

Soon after Batho's basic layout had been completed during the early 1920s, it became Bloemfontein's busiest building site by far. The new location was laid out according to the conventional grid pattern, with Fort Hare Road and Lovedale Road as the main thoroughfares (Figure 4).

Much of the house-building activity was made possible by the council's unique assisted building scheme which became the backbone of the Bloemfontein system. In his annual report for 1923-1924, the mayor, Mr J.A. Reid,115 boasted that "in the building of their houses [the Batho residents' houses] the Municipality comes generously to their assistance, granting the necessary material on easy purchase terms".116 In the annual report for the previous year, namely 1922-1923, Reid's predecessor, Mr D. Urquhart,117 explained that the building of the overwhelming majority of Batho's houses "has been assisted by the Council",118 which, in practical terms, meant the advancing of "wood and iron, windows, doors, etc. by way of loan, on which 6½% [6.5%] is chargeable".119

Mayor Reid's reference to the Batho residents who were building their houses is significant because, unlike the Johannesburg system, an important trait of the Bloemfontein system was that the houses built in Batho became the builders' property. In other words, while Batho's residents could not own the plots on which the houses were built,120 the houses could be owned.121 Thus, the municipality encouraged home ownership despite the contradiction embedded in this benefit due to the fact that black people were not allowed land ownership outside the reserves. Confirming his council's stance in this regard, Reid stated that for him personally, it had been gratifying to witness "a large proportion of them [Batho residents] building and owning their own houses".122

The prospect of home ownership, as well as the fact that builder-owners could choose from a variety of pre-approved building plans123 (see Figure 5 below) or submit their own designs for approval, was not only a significant development in terms of the general beautification of Batho but also its development as a "model location". First of all, Batho displayed a pleasing variety in terms of architecture and design, varying from four-room cottages124 to five and even six-room homes,125including verandah houses and stoep-room houses.126

Houses were built using either sun-dried bricks, also known as Kimberley bricks, or sturdier, burnt or baked bricks.127 In 1926, the superintendent of the location reported that the houses being built in Batho were "of a greatly improved type [compared] to those in Waaihoek".128 It was also mentioned that "rooms are of larger dimensions and greater attention is paid to light and air space".129 These better-quality houses were certainly made possible by the council's financial assistance, but the prospect of home ownership or "proprietorship",130 as mentioned in Umteteli wa Bantu, a weekly newspaper with a predominantly black readership, also played an important role. It was argued that home ownership not only had "a steadying effect on citizenship conduct"131 but also made the homeowners "house proud",132 and developed civic pride among them and, in turn, encouraged them to take an active part in the good governance of their location.133

The notion that the Bloemfontein system guaranteed better-quality houses was not supported by all. In fact, this system was criticised because it was argued that owner-built houses were not as durable as those built by other housing schemes.134Bloemfontein's town council defended its scheme by arguing that sturdier burnt bricks, instead of raw bricks, were used increasingly by Batho's builders, which, in turn, guaranteed better-quality houses.135 As far as the council's vision for Batho was concerned, it appears as though they not only had in mind better-quality houses but also "better-quality residents", so to speak. In his annual report for 1919-1920, Mayor Thomson stated that it was the "deliberate policy" of the council to encourage the settlement in Batho of "a large Native labour supply of the better-type natives".136It is argued that the council's desire to see these "better-type natives" (read black petty bourgeoisie) settle in the model location indicates an element of class-differentiation embedded in its vision for Batho.

Initially, all bona fide residents who were in the regular employment of whites for at least twelve months and who could produce the necessary service contracts, were issued plots in Batho.137 By 1930, the criteria were made stricter by limiting new plots to old residents of Waaihoek and married applicants only.138 Despite stricter measures, large numbers of unemployed black and some coloured people from Orange Free State towns and farms still flocked to Bloemfontein on a daily basis. Ironically, many of them were attracted by the amenities of the new location. In a leading article, The Friend stressed the council's challenge: "The more the Town Council increases the health, the comfort and the general amenities of the locations, the more attractive they become to outside Natives".139 Still, the expressed policy of the municipality, namely that "the Locations are for the accommodation of those Natives in regular employment within the proclaimed area", remained unchanged.140

"The best town-planning lines": The "model location" ideology and its origins

The description of the Orange Free State as a "model republic" dates back to the term of office (1864-1888) of the republic's fourth president, President J.H. Brand. During the Brand period, the Orange Free State had developed into a relatively well-governed and prosperous Boer republic and, according to white opinion, became widely known as a so-called "model republic",141 or "model state",142 with a "model municipality",143 and Bloemfontein was described as a "model city".144 Since then the notion of the Orange Free State as a model province and Bloemfontein as a model city had become a useful marketing tool for the local municipality to promote the city and was also an effective ideological instrument to paint the new Batho location in a positive light. The municipality appears to have been fairly successful in its efforts in this regard because it prompted others also to describe Batho in "model" terms. For example, Solomon (Sol) Plaatje described Batho as a "model location"145 after his visit to Bloemfontein in 1924. Whether Plaatje deliberately intended the description as a nod to the model city or model republic philosophy of old, is unclear.

Plaatje's description of Batho as a model location is potentially controversial and open to interpretation because most location residents' experiences of the model city were rather negative. The "model location" was, in all respects, a location founded on the principle of racial segregation and segregationist policies were as stringently enforced there as in any other location. Therefore, the use of the adjective "model" in the South African context and, specifically, in the Bloemfontein context is controversial and must, at all times, be qualified in terms of people's experiences. By and large, such assessments depended on which side of the so-called colour line people were placed.146 For Plaatje, we suggest, Batho became a model of what a location could be and also served as a model for other locations in the Union.147However, for some of Bloemfontein's councillors, the noble idea of the model city with its matching model location was difficult to resist. This was probably due to its historical roots in the model republic and model city philosophy of the late 1800s and its purported philanthropist underpinning, namely the objective to raise black and coloured people's living standards by providing them with a better living environment.

The idea of the model location dates back to 1892, when Dr Kellner first expressed the hope that Waaihoek would soon become a model location. In 1907, Mr J.W. Hancock, the inspector of Native Locations, declared that in his opinion, "the Bloemfontein Native Locations still keep up the reputation of being the best in South Africa".148 One could debate the accuracy of this statement since Hancock did not indicate how he had aarived at his judgement. To which locations were Bloemfontein's locations compared? According to which standards and criteria? Since Batho's establishment, the model location idea had, once again, been utilised as a useful ideology to raise Bloemfontein's national profile and to establish it as an exemplary location. In an address to delegates who attended the SANNC's (later renamed the African National Congress, abbreviated as ANC) annual national conference held in 1922 in Batho's newly-erected community hall, Sir Cornelis Wessels, the administrator of the Orange Free State between 1915 and 1924, reiterated this sentiment: "Bloemfontein is known as a model city, and they [the members of the Bloemfontein municipal council] were earnestly occupied in making the Bloemfontein location a model one in every respect."149

From its establishment in 1918, Batho was considered not only locally but also nationally, particularly in government circles, as a prime example of how an ideal location should be laid out and managed.150 For example, at the national conference of the Association of Superintendents of Public Parks and Gardens held in 1939, Bloemfontein was still praised and placed "in the front line"151 for its exemplary location. For more than two decades, that is, the 1920s and 1930s, Batho set the example of the ultimate model location created on "the best town-planning lines".152To an extent, Batho became a national blueprint for an ideal South African model location. Apart from its "exemplary" physical layout, Batho also set an example for the residents' involvement in a variety of issues, ranging from which public amenities had to be built first, to the naming of streets and sections.153 Therefore, it came as no surprise when another important piece of Union legislation, namely the Natives (Urban Areas) Act (No. 21 of 19 2 3)154 was based, to quote Mayor Urquhart, on the "wisdom of our Municipal Native Policy".155

According to Urquhart, the 1923 Act adopted "in toto the principles and practice that has been evolved [sic] during the past 10 years in providing decent surroundings and sanitary homes for our native citizens".156 Noteworthy is Urquhart's reference to "decent surroundings" which, among other things, included the provision of adequate space for front gardens and backyards on individual plots, communal allotment gardens, public parks, squares, football fields and croquet courts.157 Of particular importance is the municipality's expressed wish that the Batho residents' sanitary homes had to be built in "garden areas of 50 ft by 75 ft".158This meant that Batho's plots were considerably larger than the minimum size of 50 by 50 feet prescribed by the Model Location Regulations,159 discussed below. Batho's blueprint - the so-called Location Plan160 - also stipulated that no plot was to be smaller than 50 by 75 feet. Although the increased size of Batho's plots allowed for the building of bigger houses, the primary reason was to provide sufficient space for the laying out of ornamental gardens in the front of the dwelling and vegetable gardens at the back, hence the use of the term "garden areas". While adequate space was indeed allowed for the laying out of gardens, their maintenance was challenged by the inadequate provisioning of water because water had to be fetched in buckets from stand-alone taps installed at intervals on the pavements.161

We argue that the allocation of space for gardens and backyards to promote so-called "aesthetic values"162 became an important consideration in the municipality's quest to turn Batho into a model location.163 Thus, the link between the idea of a "hygienic Native township" which provided "decent surroundings" in the form of garden areas and the consideration of aesthetic values is crucial to an understanding of the municipality's model location ideology since it meant much more than merely creating a clean living environment for Batho's residents. On the one hand, it indicates the influence of international town planning trends such as the Garden City Movement. On the other hand, it may also be understood in terms of the sanitation syndrome concerns since it involved the founding of a segregated hygienic Native township primarily to appease Bloemfontein's anxious whites. Nonetheless, providing sizeable plots and garden areas for location residents was an important aspect of the Natives' Urban Areas Act's main objective to establish segregated yet orderly and well laid-out locations such as Batho and, in the process, to eradicate urban slums. Furthermore, gardening was viewed increasingly by (paternalistic?) English administrators as a handy, useful tool to suppress black militancy by channelling location residents' frustrations into acceptable, so-called "decent" pastimes.164

Another important objective of the mentioned Act was to implement a sound financial administrative system for locations. Also in this respect, Batho was considered an example of how an orderly location was expected to be administered and managed. Moreover, the Act provided for a level of participative governance in the form of consultative forums known as Advisory Boards or, as in the case of Bloemfontein, the Native Advisory Board (NAB).165 These boards offered black communities a limited say in the management of their "own affairs" and were to "advise" the superintendent of respective locations on location matters. In turn, the superintendent was to act as a channel to the council on the board's behalf.166 Once again, Bloemfontein's Native Advisory Board was considered a prime example of good governance. Importantly, however, it had no decision-making powers.167

An important component of the 1923 Act was the list of Model Location Regulations168 framed under Section 23(3) and published as Government Notice No. 672 of 1924. These regulations, which included the so-called "complements of a model location"169 were considered essential for creating such a location. They defined the duties and responsibilities of the local authority, the Advisory Board and the superintendent of the location170 as well as the duties and responsibilities of the standholder[s],171 such as the proper maintenance of their plots. Needless to say, by the time the Act was passed, most of the regulations had already been implemented by Bloemfontein's town council, including the Native Advisory Board, the so-called "blockman" (ward councillor) system, in terms of which the location was divided into "blocks" (or wards) with each block being represented by an elected block-man,172and the creation of an orderly and well laid-out location based on a leasehold tenure system. It is noteworthy that many of Batho's block-men were efficient and contributed to the success of the model location. Most of Batho's streets were named after these and other block-men, such as Abel Dilape, Abel Jordaan, Richard Matli, Jan Mocher, Jacob Sesing and Joseph Twayi.173

In addition to the framing of the Model Location Regulations, the 1923 Act also formally declared all urban areas in the Union that had been set aside as residential areas for black and coloured people, and provided detailed descriptions of the boundaries of each so-called "Native location". In terms of the provisions of the Act, the minister of Native Affairs declared Bloemfontein an urban area and approved of the following area which had been defined, set apart and laid out by the municipality as an officially recognised Native location:

The area of the town lands bounded on the west by the railway line to Johannesburg; on the north by the goal grounds (southern fence), continuing in a straight line up to the Dewetsdorp Road, then along the west side of this road up to a point in a straight line with the western boundary fence of the Belmont Hospital grounds; on the east by a straight line from the latter point to a point connecting with the camp fence immediately south-east of the Kaffirfontein Police Station and from there in a straight line to the Railway crossing (Hamilton).174

This area became known as Batho Town, later designated Batho Location and eventually only as Batho. The residents themselves often referred to Batho as the Bantu Location or Bantu-Batho Location.175

"The best in South Africa": Impressions of the "model location"

Bloemfontein's municipal officials, particularly Mr J.R. Cooper, who served as superintendent of the locations from 1923 to 1945, went to great lengths to establish and promote Batho as a model location. From the municipality's perspective, it had succeeded in its endeavours because as a model location Batho was held in high esteem nationally until the end of the 1930s, when economic decline and other social ills signalled the end of Batho's "golden age".176 The municipality's achievement was acknowledged by some of Bloemfontein's white residents who supported the concept of the "great native location"177 as an idealised future black location laid out at a distance from white Bloemfontein. It was argued that the creation of such an ideal native location (read model location) would ultimately have been to the advantage not only of Bloemfontein's black residents but also its white residents.178

The important question that must be asked, however, is whether Batho's residents themselves also considered their new location a model one. If the letters written to newspapers, such as The Friend and Umteteli wa Bantu, are an indication of popular opinion among Bloemfontein's black literate class, that is, the "better-type natives" who the council desired to settle in Batho, it seems as though most of them were initially impressed with their new location. However, the objectivity of these opinions, particularly those expressed in The Friend, should be scrutinised because there is the possibility that personal viewpoints might have been influenced by the slanted publicity given to Batho in the mainstream media.

As early as 1918, a resident of Cape Stands, who called himself Askari, wrote that despite Batho's shortcomings, such as the lack of electricity and tarred roads, he nevertheless thanked the council for making "the Bloemfontein location what it should be, the best in South Africa".179 Mr B.M. Mlamleli, a resident of the Mahlomola section in Batho, was of the opinion that Batho's residents wanted the city fathers to "continue to 'Bloemfontein', which simply means to hold up the torch".180 Mlamleli wrote that the model location "set an example which the Government even had to copy".181 Msimang, an outspoken critic of the municipality, expressed the view that in the case of Batho, "Bloemfontein stands alone as an example of good administration".182

Apart from individuals, political organisations such as the SANNC also praised Batho. Like Msimang, the SANNC was often highly critical of the municipality. Still, it expressed "its highest appreciation of the efforts of the Town Council of Bloemfontein in developing native interests and advancing the conditions in the Locations",183 and "hoped that other cities and towns will follow this praiseworthy example".184 A more objective source of black people's opinions, namely Umteteli wa Bantu, was also surprisingly generous in its praise of the model location. Batho was described as an "abode of moral and physical healthfulness" and "an object lesson to other municipalities".185

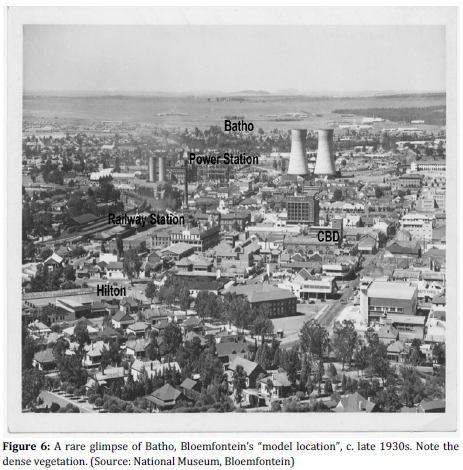

An aerial photograph of Bloemfontein taken towards the end of the 1930s depicts Batho as a green and verdant location (see Figure 6 above). Whether Batho was still the "abode of moral and physical healthfulness" it had been during the early 1920s, is unclear. At face value, however, the municipality's efforts to create what it called "decent surroundings" by considering "aesthetic values" in the form of "garden areas" seemingly had paid off.

Conclusion

The idea of the "model location" was no novelty when Batho was described as such during the 1920s and 1930s. The term, which traces its roots to the time of President Brand's so-called "model republic", was already used by Dr Kellner in the 1890s when he described the upgraded Waaihoek location as a model location. Bloemfontein's municipality saw the potential of using this description as a useful tool to promote the city's public image when, for a number of reasons, it was decided to establish Batho as a township for Bloemfontein's black and coloured people. The model location idea is indeed controversial and even dubious not only when Batho is considered in terms of the sanitation syndrome theory, for example, but also when compared with Bloemfontein's white suburbs of that time. However, this should be viewed in the context of the socio-political period under discussion, namely the 1920s and 1930s. It is argued that in Batho's case, the "model location" idea went beyond being a mere theoretical and ideological construct, as had been the case with other model native villages. In Batho's case, the idea also materialised in practical terms for a number of reasons, such as the concession of home ownership, financial assistance provided to owner-builders, sturdy houses built on plots big enough for front gardens and other benefits provided in terms of the Bloemfontein system. Added to these was the municipality's commitment to establish and develop Batho as a model location and, as a result, the pride residents took in their new township.

The Natives' Urban Areas Act and its Model Location Regulations may be considered a yardstick against which Batho may be measured. Important regulations of the Act were based on Batho's example. Not only did Batho comply comfortably with the minimum requirements of these regulations, but the municipality also overcompensated in some respects, such as the average size of plots or garden areas and the provisioning of amenities which were not normally provided in the typical location. From the outset, Bloemfontein's municipality was determined not only to create a model location in terms of general management, administration, layout and amenities but also in terms of aesthetics. At the time of Batho's founding, this aspect was certainly not the norm as far as location planning in the Union was concerned. In this regard, the municipality set a new standard for considering aesthetic values for Batho's layout and, as a result, managed to have a positive influence on the appearance of the residents' domestic environment. While the municipality is condemned for its complicity in establishing a racially-segregated location to appease the white electorate, it is credited for establishing what was described as an "exemplary" location. When compared with the conditions in locations elsewhere in the Union, such as those described by Dr Jabavu, it may be argued that the notion of Batho as a model location was not entirely without merit.

REFERENCES

Anon., Bloemfontein's Best (brochure) (D. Francis & Co., Bloemfontein, 1930). [ Links ]

Anon., Twentieth Century Impressions of Orange River Colony and Natal: Their History, People, Commerce, Industries and Resources (Lloyd's Greater Britain Publishing Co., Natal, 1906). [ Links ]

Barlow, A.G., Almost in Confidence (Juta & Co., Cape Town, 1952). [ Links ]

Barlow, T.B., The Life and Times of President Brand (Juta & Co., Cape Town, 1972). [ Links ]

Bidwell, M. and Bidwell, C.H., Pen Pictures of the Past (edited by K. Schoeman; Vrijstatia 5) (Human & Rousseau, Cape Town, 1986). [ Links ]

Burman, J., Disaster Struck South Africa (Struik, Cape Town, 1971). [ Links ]

Christopher, A.J., "From Flint to Soweto: Reflections on the Colonial Origins of the Apartheid City", Area, 15, 2 (1983). [ Links ]

Clapson, M., "The Suburban Aspiration in England since 1919", Contemporary British History, 14, 1 (2000). [ Links ]

Cooper, J.R., "The Municipality of Bloemfontein: Native Housing and Accommodation", South African Architectural Record, 28, 6 (June 1943). [ Links ]

Davenport, T.R.H., The Beginnings of Urban Segregation in South Africa: The Natives (Urban Areas) Act of 1923 and its Background (Occasional Paper No. 15, Institute of Social and Economic Research, Rhodes University, 1971). [ Links ]

David, G., "S. Patrick's Mission, Bloemfontein", Quarterly Paper, 69 (July 1885). [ Links ]

Dawson, W.H., South Africa: People, Places, and Problems (Longmans, Green & Co., London, 1925). [ Links ]

Epprecht, M., "The Native Village Debate in Pietermaritzburg, 1848-1925: Revisiting the 'Sanitation Syndrome'", Journal of African History, 58, 2 (2017). [ Links ]

Erasmus, P.A., Die Invloed van die Mate van Etniese Bewustheid op die Volksontwikkeling van die Stedelike Suid-Sotho (Research Report, ISEN, University of the Orange Free State, 1983). [ Links ]

Haasbroek, J., "Die Rol van die Engelse Gemeenskap in die Oranje-Vrystaat 18481859", Memoirs van die Nasionale Museum, Bloemfontein, 15 (December 1980). [ Links ]

Haasbroek, J., "Founding Venue of the African National Congress (1912): Wesleyan School, Fort Street, Waaihoek, Bloemfontein", Navorsinge van die Nasionale Museum, Bloemfontein, 18, 7 (November 2002). [ Links ]

Haasbroek, J., "The Native Advisory Board of Bloemfontein, 1913-1923", Navorsinge van die Nasionale Museum, Bloemfontein, 19, 4 (July 2003). [ Links ]

Hellman, E. (ed.), Handbook on Race Relations in South Africa (Oxford University Press, Cape Town, 1949). [ Links ]

Howard, E., Garden Cities of To-morrow (Attic Books, Eastbourne, 1985). [ Links ]

Jabavu, D.D.T., The Black Problem: Papers and Addresses on Various Native Problems (Negro Universities' Press, New York, 1969). [ Links ]

Kieser, A., "Bloemfontein in its early days", The Friend, 20 November 1933. [ Links ]

Krige, D.S., "Afsonderlike ontwikkeling as ruimtelike beplanningstrategie: 'n toepassing op die Bloemfontein - Botshabelo - Thaba Nchu-streek", D.Phil. thesis, University of the Orange Free State, 1988. [ Links ]

Krige, S., "Bloemfontein", in Lemon, A. (ed.), Homes Apart: South Africa's Segregated Cities (David Philip, Cape Town, 1991). [ Links ]

Le Roux, C., "J.R. Cooper as Township Manager of Mangaung at Bloemfontein, 19231945", Navorsinge van die Nasionale Museum, Bloemfontein, 26, 1 (December 2010). [ Links ]

Le Roux, C.J.P., "Die Bloemfonteinse Oproer van 1925", Contree, 29 (April 1991). [ Links ]

Letsatsi, P., "Batho's Street Names: A Rich Historical Reference", Culna, 67 (November 2012). [ Links ]

Mabin, A., "Origins of Segregatory Urban Planning in South Africa, c. 1900-1940", Planning History, 13, 3 (1991). [ Links ]

Mäki, H., "Comparing Developments in Water Supply, Sanitation and Environmental Health in Four South African Cities, 1840-1920", Historia, 55, 1 (May 2010). [ Links ]

Mancoe, J., First Edition of the Bloemfontein Bantu and Coloured People's Directory (A.C. White P. & P. Co., Bloemfontein, 1934). [ Links ]

Maylam, P., "Explaining the Apartheid City: 20 Years of Southern African Urban Historiography", Journal of Southern African Studies, 21, 1 (March 1995). [ Links ]

Morris, P., A History of Black Housing in South Africa (South Africa Foundation, Johannesburg, 1981). [ Links ]

Murray, A.V., The School in the Bush: A Critical Study of the Theory and Practice of Native Education in Africa (Frank Cass & Co., London, 1967). [ Links ]

National Museum Oral History Collection, Interview with Ms D. Maritz conducted by D. du Bruyn, Heidedal, 22 February 2008. [ Links ]

"Old Bloemfonteiner" (pseudonym), "When Bloemfontein's Population is 250 000: Town Planning for the Future", The Friend, 5 October 1936. [ Links ]

Phillips, H., "'Black October': The Impact of the Spanish Influenza Epidemic of 1918 on South Africa", Archives Year Book for South African History, 53, 1 (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1990). [ Links ]

Plaatje, S.T., Native Life in South Africa, before and since the European War and the Boer Rebellion (Negro Universities' Press, New York, 1969). [ Links ]

Plaatje, S.T., "The Native Mind", The Friend, 7 December 1927. [ Links ]

Rheinallt Jones, J.D. and Saffery, A.L., "Social and Economic Conditions of Native Life in the Union of South Africa", Bantu Studies, 7, 4 (December 1933). [ Links ]

Rich, P.B., "Ministering to the White Man's Needs: The Development of Urban Segregation in South Africa, 1913-1923", African Studies, 37, 2 (1978). [ Links ]

Rogers, H., Native Administration in the Union of South Africa: Being a Brief Survey of the Organisation, Functions and Activities of the Department of Native Affairs of the Union of South Africa (Wits University Press, Johannesburg, 1933). [ Links ]

Schoeman, K., Bloemfontein: Die Ontstaan van 'n Stad, 1846-1946 (Human & Rousseau, Kaapstad, 1980). [ Links ]

Schoeman, K., Vrystaatse Erfenis: Bouwerk en Geboue in die 19de eeu (Human & Rousseau, Kaapstad, 1982). [ Links ]

Schoeman, K. (ed.), Early White Travellers in the Transgariep 1819-1840 (Protea Book House, Pretoria, 2003). [ Links ]

Sekete, A.M., "The History of the Mangaung (Black) Township", M.A. mini-dissertation, University of the Free State, 2004. [ Links ]

Selope-Thema, R.V., "The African To Day", Umteteli wa Bantu, 12 January 1929. [ Links ]

Senekal, W.F.S., Gedifferensieerde Woonbuurtvorming binne die Munisipaliteit van Bloemfontein: 'n Faktorekologiese Toepassingstudie (Research Report 2: Part I, ISEN, University of the Orange Free State, 1977). [ Links ]

Sevenhuysen, K., "Owerheidsbeheer en -wetgewing rakende stedelike swart behuising voor en gedurende die Tweede Wereldoorlog", Historia, 40, 1 (May 1995). [ Links ]

Sevenhuysen, K., "Swart Stedelike Behuisingsverskaffing in Suid-Afrika, ca. 19231948: 'Wanneer meer minder kos', Finansiële Verliese versus Welsyns- en Gesondheidswinste", New Contree, 64 (July 2012). [ Links ]

Smit, P., "Historiese Grondslae van Swart Verstedeliking in Suid-Afrika", South African Historical Journal, 19 (November 1987). [ Links ]

Snyman, P.M., "Die Grondslae van die Historiese Aardrykskunde en die Toepassing van die 'Spesifieke Periode'-metode op die Historiese Aardrykskunde van Bloemfontein tot 1900", MA dissertation, University of the Orange Free State, 1969. [ Links ]

Standaert, E., A Belgian Mission to the Boers (T. Maskew Miller, Cape Town, 1917). [ Links ]

Swanson, M.W., "The Sanitation Syndrome: Bubonic Plague and Urban Native Policy in the Cape Colony, 1900-1909", The Journal of African History, 18, 3 (1977). [ Links ]

Taljaard, J.C., "Die Naturelle-administrasie van die Stad Bloemfontein", MA dissertation, University of Stellenbosch, 1953. [ Links ]

Torr, L., "Providing for the 'Better-class Native': The creation of Lamontville, 19231933", South African Geographical Journal, 69, 1 (1987). [ Links ]

"Vagabond" (pseudonym), "Early Days in Bloemfontein: Reminiscences of a Resident of Forty-five Years", The Friend, 27 September 1924. [ Links ]

Van Aswegen, H.J., "Die Verhouding tussen Blank en Nie-Blank in die Oranje-Vrystaat, 1854-1902", Archives Year Book for South African History, 34, 1 (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1977). [ Links ]

Van Aswegen, H.J., "Die verstedeliking van die Nie-Blanke in die Oranje-Vrystaat, 1854-1902", South African Historical Journal, 2 (November 1970). [ Links ]

Van der Bank, D.A., "St Patrick's Church", Restorica, 19 (April 1986). [ Links ]

Verwey, E.J. (ed.), New Dictionary of South African Biography, Volume I (HSRC, Pretoria, 1995). [ Links ]

Wessels, A. and Wentzel, M.E., Die Invloed van Relevante Kommissieverslae sedert Uniewording op Regeringsbeleid ten Opsigte van Swart Verstedeliking en Streekontwikkeling, Report IGN-TI (Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria, 1989). [ Links ]

* Currently, he is project leader of the Museum's Batho Community History Project, which collects, inter alia, information on Batho's sociopolitical history and liberation heritage. Dr Marietjie Oelofse is a senior Her research interests include oral history, as well as transitional justice, with a focus on truth commissions.

1 In the South African colonial and apartheid context, the word "township" meant a designated living area or suburb reserved for people of African origin.

2 Similarly, "location" was commonly used to refer to areas for informal living quarters for black and coloured people, usually located on the outskirts of white towns and cities. These areas are now called townships.

3 M. Epprecht, "The Native Village Debate in Pietermaritzburg, 1848-1925: Revisiting the 'Sanitation Syndrome'", Journal of African History, 58, 2 (2017), pp 259-283.

4 K. Sevenhuysen, "Swart Stedelike Behuisingsverskaffing in Suid-Afrika, ca. 19231948: 'Wanneer meer minder kos': Finansiële Verliese vs Welsyns- en Gesondheidswinste", New Contree, 64 (July 2012), pp 105-129.

5 H. Mäki, "Comparing Developments in Water Supply, Sanitation and Environmental Health in Four South African Cities, 1840-1920", Historia, 55, 1 (May 2010), pp 90-109.

6 M.W. Swanson, "The Sanitation Syndrome: Bubonic Plague and Urban Native Policy in the Cape Colony, 1900-1909", Journal of African History, 18, 3 (1977), pp 387-410.

7 P. Maylam, "Explaining the Apartheid City: 20 Years of South African Urban Historiography", Journal of Southern African Studies, 21, 1 (March 1995), pp 19-38.

8 Maylam, "Explaining the Apartheid City", p 30.

9 Epprecht, "The Native Village Debate", pp 259-283.

10 L. Torr, "Providing for the 'better-class native': The Creation of Lamontville, 19231933", South African Geographical Journal, 69, 1, 1987, pp 31-46.

11 The greater Bloemfontein area (Bloemfontein, Botshabelo and Thaba Nchu) is officially known as Mangaung, a Sesotho word meaning "place of the cheetah". Batho forms part of the Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality.

12 A Sesotho word meaning "people".

13 Waaihoek and Bloemfontein's other old locations, such as Kaffirfontein and the No. 3 Location, were demolished in the first half of the twentieth century.

14 Initially spelt Waay Hoek.

15 This historical place name is also spelt Kafirfontein or Kaffir Fontein, and was known at the time as Kaffer Fontein or Kafferfontein among the Dutch-speaking whites.

16 With the exception of Cape Stands, which was established shortly after the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902), Waaihoek, Kaffirfontein and the No. 3 Location were established during the second half of the nineteenth century.

17 Also known as Bushmen.

18 Also known as Khoe, Khoi and Khoi-Khoin.

19 In its original context, the term "Bantu-speaking" refers to a major linguistic group in Africa who spoke a group of closely-related languages, namely Nguni, Sotho-Tswana, Venda and Tsonga.

20 In this article, the word "coloured(s)" refers to people of mixed race.

21 In this article, the word "black(s)" refers to people of African origin.

22 K. Schoeman, Bloemfontein: Die Ontstaan van 'n Stad, 1846-1946 (Human & Rousseau, Cape Town, 1980), pp 1-2, 10; P.A. Erasmus, "Die Invloed van die Mate van Etniese Bewustheid op die Volksontwikkeling van die Stedelike Suid-Sotho", Research report, ISEN, University of the Orange Free State, 1983.

23 Descendants of Zulus and Xhosas. Also known as the amaMfengu.

24 See "Kaffir Location" and "Fort" in Figure 2.

25 Free State Provincial Archives, Bloemfontein (hereafter FSPA): MBL 3/1/15, Report of Superintendent of Native Locations, 1912, p 111.

26 Erasmus, "Die Invloed van die Mate van Etniese Bewustheid", pp 194-195. The Kaffirfontein Spruit is currently known as the Renoster Spruit.

27 FSPA: MBL 3/1/19, Mayor's Minutes, 1926-1927, pp 12-15; A.M. Sekete, "The History of the Mangaung (Black) Township", M.A. mini-dissertation, UOFS, 2004, pp 2-3; P.M. Snyman, "Die Grondslae van die Historiese Aardrykskunde en die Toepassing van die 'Spesifieke Periode'-Metode op die Historiese Aardrykskunde van Bloemfontein tot 1900", M.A. dissertation, UOFS, 1969, pp 157-159; A. Kieser, "Bloemfontein in its Early Days", The Friend, 20 November 1933, p 8.

28 Anon., Twentieth Century Impressions of Orange River Colony and Natal: Their History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources (Lloyd's GB Publishing, Natal, 1906), p 36.

29 H.J. van Aswegen, "Die Verhouding tussen Blank en Nie-Blank in die Oranje-Vrystaat, 1854-1902", Archives Year Book for South African History, 34, 1 (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1977); The Friend, 28 July 1921, p 4; K. Schoeman (ed.), Early White Travellers in the Transgariep 1819-1840 (Protea Book House, Pretoria, 2003).

30 Goddard was mayor of Bloemfontein from April 1883 to March 1885.

31 FSPA: MBL 3/1/1, Mayor's minute, 1885, p 10.

32 David was director of the Anglican Church's St Patrick's Mission in Bloemfontein.

33 Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (hereafter HP): G. David, "S. Patrick's Mission, Bloemfontein", Quarterly Paper, 69 (July 1885), p 137.

34 FSPA: MBL 3/1/3, Mayor's minute, 1892, p 2.

35 FSPA: MBL 3/1/5, Mayor's minute, 1897, p 5.

36 E. Howard, Garden Cities of To-morrow (Attic Books, Eastbourne, 1985), pp vi-viii.

37 M. Clapson, "The Suburban Aspiration in England since 1919", Contemporary British History, 14, 1 (2000), p 152.

38 Approximately 16.5 x 16.5 metres.

39 Kellner was mayor of Bloemfontein from April 1891 to March 1896 and again from October 1898 to December 1902.

40 FSPA: MBL 3/1/3, Mayor's minute, 1892, p 2.

41 Sowden was mayor of Bloemfontein from April 1896 to March 1898.

42 FSPA: MBL 1/2/4/1/3, Letter from acting Superintendent of Locations to Town Clerk, 18 November 1918, p 3.

43 FSPA: MBL 3/1/5, Mayor's minute, 1897, p 5.

44 J. Haasbroek, "Die Rol van die Engelse Gemeenskap in die Oranje-Vrystaat, 18481859", Memoirs van die Nasionale Museum, Bloemfontein, 15 December 1980, pp 89109.

45 The Friend, 28 July 1921, p 4; W.H. Dawson, South Africa: People, Places, and Problems (Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1925), p 249.

46 FSPA: MBL 3/1/19, Mayor's Minutes, 1924-1925, p 5.

47 Schoeman, Bloemfontein: Die Ontstaan van, pp 35, 83.

48 See, for example, the regulations in the Free State Republic's Law No. 8 of 1893. This governed black and coloured locations until 1923. See also the regulations included in the ordinances of the Orange River Colony: Ordinance No. 35 of 1903; No. 6 of 1904; No. 12 of 1904; No. 14 of 1905 and No. 19 of 1905. From 1913 to 1923, the Union Department of Native Affairs administered urban black and coloured people and locations in terms of Ordinance No. 14 of 1913. Statutes of the Union of SA, 1923, with tables of contents (alphabetical and chronological) and tables of laws, etc., repealed and amended by these statutes: Natives (Urban Areas) Act (No. 21 of 1923), p 124.

49 FSPA: MBL 1/2/4/1/2, Minutes of public meeting, Waaihoek, 13 February 1918, p 1.

50 For more information, see Maylam, "Explaining the Apartheid City", pp 22, 27-28.

51 FSPA: MBL 3/1/19, Mayor's Minutes, 1926-1927, p 12.

52 FSPA: MBL 3/1/19, Mayor's Minutes, 1926-1927, p 12.

53 R.V. Selope-Thema, "The African To Day", Umteteli wa Bantu, 12 January 1929, p 2.

54 FSPA: MBL 3/1/19, Mayor's Minutes, 1926-1927, p 12.

55 Deane was mayor of Bloemfontein from April 1927 to March 1928.

56 The Friend, 30 April 1924, p 8.

57 FSPA: MBL 3/1/19, Mayor's Minutes, 1926-1927, p 12.

58 E.J. Verwey (ed.), New Dictionary of South African Biography Volume I (HSRC, Pretoria, 1995), p 189.

59 Schoeman, Bloemfontein: Die Ontstaan van, p 285; J. Haasbroek, "Founding Venue of the African National Congress: Wesleyan School, Fort Street, Waaihoek, Bloemfontein", Navorsinge van die Nasionale Museum, Bloemfontein, 18, 7 (November 2002), p 133.

60 For more information, see Swanson, "The Sanitation Syndrome"; Maylam, "Explaining the Apartheid City", pp 24-25; A. Mabin, "Origins of Segregatory Urban Planning in South Africa, c. 1900-1940", Planning History, 13, 3 (1991), p 9; and Epprecht's critique of the sanitation syndrome theory, in Epprecht, 'The Native Village Debate".

61 Black people demanded a minimum wage between three shillings and sixpence to four shillings and sixpence. See Schoeman, Bloemfontein: Die Ontstaan van, p 284.

62 C.J.P. le Roux, "Die Bloemfonteinse Oproer van 1925", Contree, 29 (April 1991), pp 2429; Schoeman, Bloemfontein: Die Ontstaan van, pp 282-284.

63 On the commission's report, see J.C. Taljaard, "Die Naturelle-administrasie van die Stad Bloemfontein", MA dissertation, University of Stellenbosch, 1953, pp 226-228.

64 The Friend, 31 May 1928, p 17.

65 The Friend, 31 May 1928, p 17.

66 The Friend, 31 October 1924, p 8.

67 The Friend, 31 October 1924, p 8.

68 P.B. Rich, "Ministering to the White Man's Needs: The Development of Urban Segregation in South Africa, 1913-1923", African Studies, 37, 2 (1978), p 177; P. Smit, "Historiese Grondslae van Swart Verstedeliking in Suid-Afrika", South African Historical Journal, 19 (November 1987), p 16.

69 H.J. van Aswegen, "Die Verstedeliking van die Nie-Blanke in die Oranje-Vrystaat, 1854-1902", South African Historical Journal, 2 (November 1970), pp 19-37.

70 Erasmus, "Die Invloed van die Mate van Etniese Bewustheid", pp 195-196; Rich, "Ministering to the White Man's Needs", pp 177-180; Smit, "Historiese Grondslae van Swart Verstedeliking", pp 15-17; S.T. Plaatje, Native Life in South Africa, before and since the European War and the Boer Rebellion (Negro Universities' Press, New York, 1969), pp 21-32; S.T. Plaatje, "The Native Mind", The Friend, 7 December 1927, p 5; FSPA: MBL 1/2/4/1/17, Minutes of joint meeting of Native Affairs Committee and Native Advisory Board, 13 August 1929, pp 1-2.

71 Meaning people from outside Bloemfontein. FSPA: MBL 1/2/4/1/3, Letter from Superintendent of Locations to Town Clerk, 25 April 1919, p 7.

72 FSPA: MBL 1/2/4/1/3, Letter from Superintendent of Locations to Town Clerk, 25 April 1919, p 7.

73 K. Schoeman, Vrystaatse Erfenis: Bouwerk en Geboue in die 19de Reu (Human & Rousseau, Cape Town, 1982), pp 27, 30-32.

74 The Friend, 5 October 1918, p 7.

75 For more information on the epidemic, see J. Burman, Disaster Struck South Africa (Struik, Cape Town, 1971), pp 83-104.

76 The Friend, 11 January 1919, p 5.

77 The Friend, 5 October 1918, p 7.

78 The Friend, 23 December 1918, p 5; FSPA: MBL 1/2/4/1/3, Minutes of ordinary meeting of Native Affairs Committee, 1 November 1918, pp 1-2; H. Phillips, "'Black October': The Impact of the Spanish Influenza Epidemic of 1918 on South Africa", Archives Year Book for South African History, 53, 1 (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1990), pp 58-68; Burman, Disaster Struck South Africa, pp 86-87, 94.

79 For the complete memorandum and report, see The Friend, 23 December 1918, p 5; 24 December 1918, p 6; 25 December 1918, p 4; 27 December 1918, p 4; 28 December 1918, p 6; and 31 December 1918, p 4.

80 The Friend, 23 December 1918, p 5.

81 The Friend, 9 January 1919, p 8.

82 The Friend, 13 January 1919, p 8.

83 The Friend, 13 January 1919, p 8.

84 Thomson was mayor of Bloemfontein from April 1918 to March 1920.

85 The Friend, 11 January 1919, p 5.

86 The Friend, 13 January 1919, p 8.

87 The Friend, 13 January 1919, p 8.

88 The Friend, 13 January 1919, p 8.

89 FSPA: MBL 1/2/4/1/6, Minutes of ordinary meeting of Native Affairs Committee, 7 April 1924, p 2.

90 FSPA: MBL 1/2/4/1/6, Minutes of ordinary meeting of Native Affairs Committee, 7 April 1924, p 2.

91 The Friend, 25 March 1927, p 9; Die Volksblad, 25 March 1927, p 5.

92 D.A. van der Bank, "St Patrick's Church", Restorica, 19 (April 1986), pp 15, 18.

93 FSPA: MBL 3/1/19, Mayor's Minutes, 1919-1920, p 8.