Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.52 n.3 Stellenbosch 2016

https://doi.org/10.15270/52-2-518

ARTICLES

The social functioning of women with breast cancer in the context of the life world: a social work perspective

Jonita van WykI; Charlene CarbonattoII

IPost graduate student, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

IIDepartment of Social Work & Criminology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Breast cancer is the most common form of cancer in women worldwide (CANSA, 2010). The goal of this study was to explore the social functioning of women with breast cancer. A qualitative research approach was followed with a collective case study research design. In this study non-probability, purposive sampling was used to select participants. One of the themes generated was the impact of breast cancer on social functioning in the context of the life world. This theme includes changes in personality; feeling like a woman; changes in spiritual aspects; and self-image. Research showed that there were mainly positive changes experienced.

INTRODUCTION

Social work practice is focused on the improvement or restoration of social functioning of individuals, families, groups and communities (Barker, 2003:408). Social functioning means the fulfilment of an individual's roles which originate as a result of the individual's interactions with his/her own self, family, society and environment (Barker, 2003:403; New Social Work Dictionary., 1995:58). Health care social work practice focuses on the social functioning of individuals, families, groups and communities afflicted by illness or disability. Ross and Deverell (2004:36) explain that disabling illnesses cause strong emotional reactions in the patient as well as the family. Many illnesses, whether acute or chronic, can cause disequilibrium, but chronic illnesses can affect the individual in different ways throughout the duration of his/her lifetime. For the purpose of this study, the focus was on cancer, particularly breast cancer and how it affects women's social functioning. The life world of women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer underlines the need for research in social functioning. Thus the focus in this study was on how breast cancer affects the social functioning of women.

GOAL

The goal of the study was to explore the social functioning of women with breast cancer. The specific objective that will be discussed in this article is to explore how breast cancer affects the functioning of a woman as an individual, mother and wife.

RESEARCH QUESTION

The research question is a "life-world-evoking question" where the experience of a life world is described as richly as possible (Todres, 2005:108). The research question was: How does breast cancer affect the social functioning of women? The specific area of the research question that will be discussed in this article is the social functioning of a woman with breast cancer within the context of her life world.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The concept of "role" is central to the definition of social functioning because it is key to the approach to defining the person and social environments (Ashford & LeCroy, 2010:29). Role theory entails that there is a set of social expectations associated with certain roles, and people internalise and assume these role expectations (Kimberley & Osmond, 2011:415). Role theory examines how roles affect the behaviour, attitudes, cognition and social interactions of a person occupying one or more roles (Diekman, 2007:763). Kimberley and Osmond (2011:418) believe that physical health problems should also be taken into account because they could influence changes in role functioning and social responsibilities that are associated with these. Role theory can be used to assess the way in which breast cancer affects the social functioning of women.

RESEARCH METHOD

A qualitative research approach was followed to investigate the social functioning of women with breast cancer. A case study research design was followed in order to discover the meaning that people assign to a social phenomenon. More specifically, the collective case study research design was used so that the different cases could be compared with each other to identify similarities and differences between them (Babbie, 2010:309; Flick, 2000:147; Fouché, 2005:272; Nieuwenhuis, 2007a:75).

The population focused on women who were diagnosed with breast cancer, receiving treatment and were clients of CANSA Potchefstroom. Non-probability sampling, specifically purposive sampling, was used in order to meet the specific criteria of the study. In purposive sampling it is believed that a particular group is important to the study because its members hold the data necessary to perform the study and the participants must have specific homogeneous characteristics (Alston & Bowles, 2003:90; Nieuwenhuis, 2007a:79; Royse, 2011:204-205). The sampling criteria for the women were as follows:

• Between the ages of 30-70 years;

• Diagnosed with breast cancer;

• Currently or recently undergone surgical, radiation or chemotherapy treatment for the disease;

• Residing in the Potchefstroom area;

• Currently part of the client system of CANSA Potchefstroom.

The director of CANSA Potchefstroom provided the researcher with the contact details of women who met the criteria. The first 10 women whom the researcher contacted and who met the criteria were selected. They were invited for an interview where the researcher explained the research study. Once they had signed a letter of informed consent, the interviews were arranged. Ten participants were selected. Two participants formed part of the pilot study and the remaining eight participants formed part of the main study.

Face-to-face, semi-structured interviews were used to collect data from participants. This gives the opportunity for the interview to move into new directions (Greeff, 2011:351-352; Nieuwenhuis, 2007a:87). The interview schedule had themes that focused on different aspects of social functioning. The interviews were voice recorded with the permission of the participants and were then transcribed and the data analysed.

Schurink, Fouché and De Vos (2011:403) combined the theories of Cresswell and Marshall and Rossman to create a linear process of data analysis which the researcher used during the research process. These steps include planning for the recording of data, data collection and preliminary analysis; managing data and reading; generating categories, themes and patterns, and coding data; testing understandings and searching for alternatives and representation of data (Schurink et al., 2011:403-419). Trustworthiness of data was ensured by confirming data with participants during an information session (Nieuwenhuis, 2007b: 113-114).

ETHICAL ISSUES

Certain ethical issues were considered during the research project. Informed consent was obtained through signed informed consent forms that described the research and served to prepare the participants. Participants were informed that the research is voluntary and that they are free to terminate the interview at any point during the research process. Confidentiality was maintained through keeping participants' names private and assigning numbers to each participant during the research study. Debriefing was done with all participants to ensure that no harm was done. Avoidance of harm was very important throughout the research process and the researcher was attentive to the emotions of the participants. Methods of dealing with possible emotional harm were planned beforehand and followed through after the research was completed.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The study had certain limitations because of the nature of the research. Firstly, the sampling of participants did not occur as planned. CANSA Potchefstroom experienced a decrease in the number of breast cancer patients during the time that sampling for the research project took place, which meant that fewer participants were available for research. All the participants were white, which provided the study with a homogeneous group, but one that lacked cultural diversity or representativeness. Not all the participants received the same type of treatment for breast cancer and not all participants were diagnosed at the same stage of breast cancer. The different treatment options caused different side-effects and different levels of intensity were experienced in terms of the side-effects. Some participants had stage 1 breast cancer, while others had metastasised breast cancer, which means that their prognosis was worse. This resulted in the views of the sample differing as the sample was based on their different prognoses. Because of the qualitative nature of the research and the small sample, the results of this study cannot be generalised or transferred. The results from this study are the personal views of this sample and their descriptive experiences.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Cancer

Cancer is not a single illness; it is a term used to refer to a group of diseases and there are more than 100 types of cancer (Meric-Benstam & Pollock, 2010; Rees, 2004:4; Ross & Deverell, 2004:116; Ross & Deverell, 2010:134). Statistics estimate that cancer accounted for 7.6 million deaths in 2008 (WHO, 2013a). It is estimated that the number of deaths as a result of cancer will increase by 45% from 2007 to 2030 (from 7.9 million to 11.5 million), largely due to an aging population (WHO, 2008). Cancer develops when a cell changes in quality and is characterised by the uncontrolled division of these abnormal cells (Oxford Concise Medical Dictionary, 2010:109; Rees, 2004:5). Cancer cells need blood in order to grow; therefore they release a chemical stimulant that stimulates new blood vessels to nourish the cancer so that uncontrolled growth can continue to take place (Alberts, 2012:6). These cancer cells invade surrounding tissue and spread through either the blood stream or lymphatic system to other body sites; this is called metastasis (Oxford Concise Medical Dictionary, 2010:109; Pervan, Cohen & Jaftha, 1995:772). A tumour is defined by Pervan et al. (1995:783) as "an abnormal or morbid swelling or enlargement in any part of the body."

Breast cancer

The breast is a fibrofatty organ which responds to recurring hormone production and contains structures for milk production (Kimmick & Muss, 2009). Cancer of the breast is defined as "a malignant tumour of the breast, usually a carcinoma" (Oxford Concise Medical Dictionary, 2010:97). The earliest stages of breast cancer are a ductal carcinoma in situ, where the cancer is confined to the milk ducts of the breast, and lobular carcinoma in situ, where the cancer is in the lobules of the breast (Oxford Concise Medical Dictionary, 2010:224,424).

In both developing and developed countries breast cancer is one of the most prominent cancers in women and accounts for 16% of all female cancers (WHO, 2013b). Breast cancer is one of the five leading causes of death as a result of cancer worldwide and accounted for 458 000 deaths in 2008 (WHO, 2013a). Breast cancer is the second most common cancer in the world and one of the most common cancers in the African region (Longo, 2012; WHO, 2012). There are 8 000 new cases of breast cancer diagnosed in South Africa per year and there were 3156 deaths in 2000 as a result of breast cancer (Apffelstaedt, 2008; South African Medical Research Council, 2010).

Cancer treatment

The purpose of cancer treatment is primarily to eradicate cancer, but if that cannot be accomplished, the purpose shifts to preserving quality of life and extending life (Sausville & Longo, 2012). The goal of adjuvant therapy is to kill cancer cells that have escaped the breast and lymph nodes and to prevent macro metastases, which greatly improves chances of survival (Giuliano & Hurvits, 2013; Lippman, 2012). The type of cancer treatment is determined by the stage of the disease (Hunt, Newman, Copeland & Bland, 2010). Sausville and Longo (2012) categorised cancer treatment into the following three groups:

• Surgical;

• Radiation therapy;

• Chemotherapy (including hormone therapy).

Surgical

Surgery is used for prevention, diagnosis, staging, treatment, palliative care and rehabilitation in cancer care (Sausville & Longo, 2012). A biopsy is used as a diagnostic tool where as much tissue is removed as is safely possible to be examined (Rees, 2004:20; Sausville & Longo, 2012). The findings from a biopsy assist in histology, grading of a tumour and treatment planning (Meric-Benstam & Pollock, 2010).

Lymph nodes are an important component in cancer treatment, because breast cancer has the ability to spread via the lymph nodes; therefore surgical interventions include draining or removing lymph nodes (Meric-Benstam & Pollock, 2010). A lymphadenectomy is used to reduce the risk of recurrence, for staging and has been proven to increase overall survival rate (Meric-Benstam & Pollock, 2010).

According to the Oxford Concise Medical Dictionary (2010:427) a lumpectomy is:

An operation for breast cancer in which the tumour and surrounding breast tissue are removed: muscles, skin, and lymph nodes are intact.

According to the Oxford Concise Medical Dictionary (2010:440-441), a mastectomy is:

The surgical removal of a breast. Simple mastectomy, performed for extensive but not necessarily invasive tumours, involves simple removal of the breast; the skin and if possible the nipple may be retained and a prosthesis may be inserted under the skin to give the appearance of normality. When breast cancer has spread to involve the lymph nodes, radical mastectomy may be performed. This classically involves removal of the breast with the skin and underlying pectoral muscles together with all the lymphatic tissue of the armpit.

RADIATION THERAPY

Radiation therapy entails the use of high-dose radiation to a localised target and keeping the dose to normal tissue minimal (Engel-Hills, 1995:185). Radiation causes damage to cell DNA and causes damage to the cells' reproductive ability (Meric-Benstam & Pollock, 2010; Sausville & Longo, 2012). Side effects associated with radiation therapy depend on the site, dose and volume of treatment as well as the individuals' response to treatment and can be acute or may occur weeks or even years after treatment (Brennan, 2004:229; Meric-Benstam & Pollock, 2010; Rees, 2004:51). Side-effects include inflammation, fatigue, nausea, diarrhoea, skin soreness, weight loss, temporary change in skin colour and temporary or permanent hair loss (Brennan, 2004:229; Rees, 2004:51; Ross & Deverell, 2010:137; Sauseville & Longo, 2012).

CHEMOTHERAPY

Chemotherapy interferes with the cell division of normal cells and cancer cells but especially cells that divide rapidly (Rees, 2004:59). Different chemotherapeutic agents interfere with different phases in the cell cycle, and when they are combined they have the advantages of maximum cell kill, broader range of coverage and delayed drug-resistance (Meric-Benstam & Pollock, 2010).

Chemotherapy is the use of chemical agents in the treatment of cancer as the initial treatment or in conjunction with surgery and/or radiation therapy, or in instances where surgery and radiation therapy are not possible (Leon, De Jager & Toop, 1995:197). Adjuvant chemotherapy is given to eradicate metastatic disease and breast cancer responds well to multiple chemotherapeutic drugs (Giuliano & Hurvits, 2013; Meric-Benstam & Pollock, 2010). Giuliano and Hurvits (2013) confirm that 90% of patients with locally advanced breast cancer respond well to multi-drug chemotherapy.

HORMONE THERAPY

Some cancers are dependent on hormones for growth and hormone treatment can aid in preventing cancer cells from getting the hormones needed for their growth (Rees, 2004:67). Hormone or hormone-like agents can be given to hamper tumour growth by blocking hormones such as oestrogen for breast cancer (Meric-Benstam & Pollock, 2010). Tamoxifen is the most common drug used in breast cancer; it blocks the production of oestrogen, which stimulates cancer cell growth (Lippman, 2012; Rees, 2004:67). Tamoxifen has good results and fewer side-effects than chemotherapy and does not require the patient to undergo oophorectomy, the removal of an ovary (Giuliano & Hurvits, 2013; Oxford Concise Medical Dictionary, 2010:518). Oophorectomy is an effective treatment for eliminating oestrogen, progestin and androgens, but not a desirable option for premenopausal women (Giuliano & Hurvits, 2013).

REACTION TO CANCER

Diagnosis

The range of emotional reactions to a cancer diagnosis includes shock, disbelief, anger, fear, numbness, depression and devastation (Fitch, Bunston & Elliot, 1999). Biopsy and medical investigation can be the "most anxiety-provoking stage for many patients and families" and fear is present in all patients facing surgery for cancer (Jaftha & Brainers, 1995:174-175). Undergoing biopsy causes emotional turmoil in patients (Montgomery & McCrone, 2010:2388). Patients who continue with the process of searching for a diagnosis live with uncertainty and disruption of self-identity on a daily basis (Kralik, Brown & Koch, 2001:595). Research by Kayser and Sormanti (2002:399) shows that in the initial stage of diagnosis and treatment, women have a low sense of power and efficacy with regard to their health. People find it difficult to come to terms with the cancer diagnosis and often experience a period of dissociation or dreamlike numbness that can last for hours to days (Brennan, 2004:19). Women feel vulnerable and lost trying to understand the impact of the diagnosis on their present and future, and experience their emotional reactions as more disabling than the diagnosis until they go through the adjustment process (Kralik et al., 2001:600).

Treatment

Before the patient and family have had time to absorb the diagnosis, the cancer treatment starts and at times a surgical treatment is given even before a definitive diagnosis is made (Brennan, 2004:60). Being hospitalised can be a daunting experience and the following concerns are associated with hospitalisation: the patient is worried about the seriousness of the illness; she is unfamiliar with the hospital environment; she is worried about home life; she experiences loss of control and lack of support (Brennan, 2004:215).

Surgical intervention can mean that body image changes and a feeling of loss and intense emotion are experienced (Jaftha & Brainers, 1995:173). The negative aspects of a mastectomy are the cosmetic and psychological impacts of losing a breast (Giuliano & Hurvits, 2013). Patients who received surgical intervention for breast cancer had high levels of depression compared to patients who did not have surgery (Edwards & Clarke, 2004:572). Some women consider their breasts as an essential part of their femininity, maternity and sexuality. A re-evaluation of life and functioning after a mastectomy occurs because disfigurement is a personal and social experience (Brennan, 2004:33; Skrzypulec, Tobor, Drosdzol & Nowosielski, 2008:614). Cancer has an influence on body image, sexual functioning and intimacy, and this causes feelings of shame and embarrassment (Kayser & Sormanti, 2002:404; Venter, 2008:26).

Treatment can pose physical, social, sexual and psychological challenges for the patient and family (Semple & McCance, 2010:1285). The treatment calendar (medical appointments and length of treatment) can have a greater psychosocial impact on the patient's life than the treatment or illness (Brennan, 2004:63). During cancer treatment the patient must learn to adjust to treatment and symptoms, and later take on the task of long-term adjustment (Kulik & Kronfeld, 2005:38).

There are also positive outcomes of having cancer such as an increased appreciation of life and re-evaluating priorities (Semple & McCance, 2010:1286). Positive emotions experienced by cancer patients are empathy for others and family, gratefulness to be alive, having hope, and acceptance of the illness and side effects (Venter, 2008:25-26). Positive outcomes after cancer are personal growth, development of new perspectives, lifestyle changes and increased spirituality (Venter, 2008:40).

SOCIAL FUNCTIONING

Social functioning from a social work perspective means the fulfilment of an individual's roles that exist as a result of the individual's interactions with his/her own self, family, society and environment in order to perform tasks essential for daily living (Ashford & LeCroy, 2010:29; Barker, 2003:403; New Social Work Dictionary, 1995:58). Social functioning is related to functional status, which is a person's performance of activities associated with their roles and for women with breast cancer these activities include household, family, social, community, self-care and occupational activities (Bourjolly, Kerson & Nuamah, 1999:2). Social functioning can be linked to the concept of quality of life. Quality of life has seven core components (Brennan, 2004:38-39):

• Physical concerns such as pain and symptoms;

• Functional ability such as mobility, self-care and activity level;

• Family wellbeing;

• Emotional wellbeing;

• Treatment satisfaction;

• Sexuality including body image; and

• Social functioning (interaction with social networks).

When contemplating the implications of cancer on social functioning, several aspects need to be considered, as outlined below.

Cancer and cancer treatment may cause physical impairments that affect the functioning of a patient as well as vocational, psychological, economic and social problems (Cheville, Troxel, Basford & Kornblith, 2008:2621, 2628). Chemotherapy and radiation therapy can compromise a persons' social functioning (Bourjolly et al., 1999:3). The psychological distress that women go through during the diagnosis of breast cancer can interfere with their ability to perform everyday tasks of living (Montgomery & McCrone, 2010:2388). Because of the side effects of cancer treatment, which include nausea, pain and fatigue, people are unable to plan for the future and this causes them to disengage from previously appealing activities (Brennan, 2004:72). Cancer treatment leads to limitations in performing daily activities such as driving, walking, housework, family activities, leisure activities and self-care as well as experiencing changed roles and feelings of helplessness (Luoma & Hakamies-Blomqvist, 2004:732).

Women perceive the impact of cancer and its treatment as changes in their roles and relationships (Fitch et al., 1999). Diagnosis and treatment can rob people of family and social roles, which causes emotional distress for all involved (Werner-Lin & Biank, 2006:513). A person's ability to fulfil certain roles is linked to self-worth; thus a woman's self-worth is adversely influenced when she is unable to fulfil her roles in the family and society (Brennan, 2004:69). It is possible that role fulfilment can be linked with the concept of validation, where validation reminds people that they are valued and loved and will not be abandoned (Brennan, 2004:94). Women's social functioning is worse when they use escape-avoidance coping, or feel that cancer keeps them from doing what they want to do and that cancer threatens their self-esteem (Bourjolly et al., 1999:16).

Emotional functioning, which influences the ability to enjoy life, is affected and this causes emotional reactions such as being bad-tempered, depression, lack of tolerance, bitterness, and fear of pain and death (Luoma & Hakamies-Blomqvist, 2004:732).

A study by Montazeri, Vahdaninia, Harirchi, Ebrahimi, Khaleghi and Jarvandi (2008) tested the emotional functioning of patients at the start of treatment, with a follow-up assessment during treatment and 18 months after treatment. The study showed poorer emotional functioning at 18 months compared to the baseline assessment at the start of treatment.

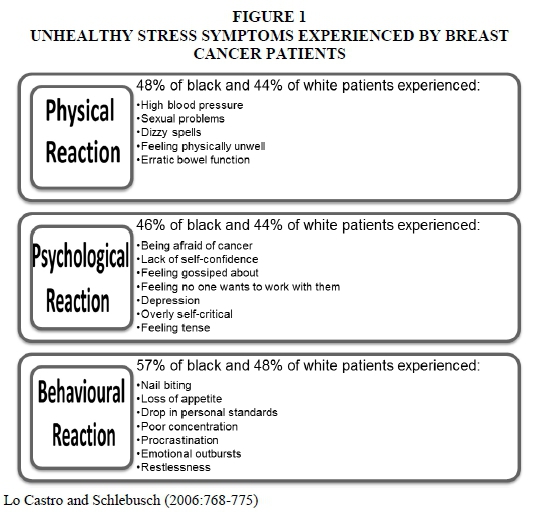

South African research indicates that breast cancer patients experienced unhealthy stress symptoms. These symptoms are described in the following figure by Lo Castro and Schlebusch (2006:768-775). Lo Castro and Schlebusch (2006:768-775)

The figure indicates the different stress symptoms experienced by patients with breast cancer. These symptoms include physical, psychological and behavioural reactions. Unhealthy stress symptoms can influence a patient's social functioning as a result of emotional outbursts, depression and feeling physically unwell.

RESEARCH FINDINGS

Profile of participants

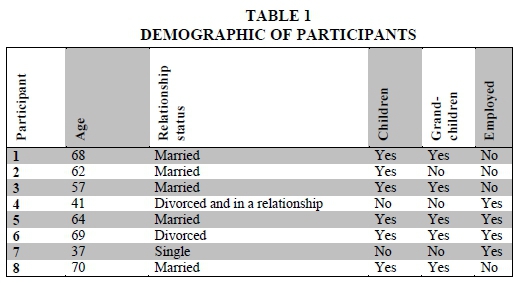

The demographic information of the participants is described in the following table:

The participants' ages ranged from 37 to 70 years with the average age being 58.5 years old. Five participants were married, one was in a relationship, one was divorced and one single. Six of the participants had children and five had grandchildren. Four participants were employed at the time of the interview.

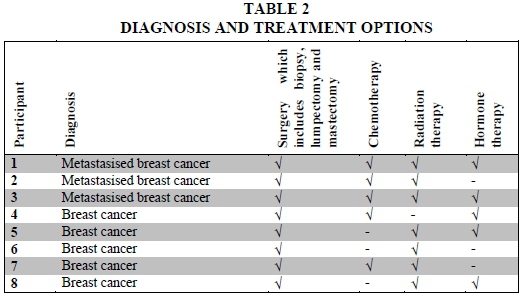

All participants were diagnosed with breast cancer and some had breast cancer that had metastasised to other areas of the body. The diagnosis and treatment options of the participants are described in the following table:

All participants received some form of surgery including biopsy, lumpectomy, lymph node removal and mastectomy. Five participants received chemotherapy and seven received radiation therapy. Five participants were receiving hormone therapy at the time of the interviews. The profiles of the participants show similarities and differences and this helped to put the data collected into perspective.

A theme and sub-themes generated from the data are discussed next.

Theme: Social functioning in the context of life world

This theme is focused on the participant herself and her personal experience with cancer. This theme is divided into four sub-themes, namely changes in personality; feeling like a woman; changes in spiritual aspect; and self-image.

Sub-theme 2.1: Changes experienced in personality

A person's identity can be described as follows (Little, Paul, Jordens & Sayers, 2002:171):

[the] sense of being this person, with attributes, acquisitions and capabilities, which condition the interactions between the person and the social systems he or she lives in.

Participants were given the opportunity to discuss the possible changes that they experienced in their personality.

"Jy worry nie meer so erg oor klein nitty gritty stuff nie, waaroor jy jou gewoonlik sou ontstel het of iets ... don't sweat the small stuff."/ "You don't worry so much about the small nitty gritty stuff anymore, stuff that would normally have upset you or something ... don't sweat the small stuff."

"Ewe skielik is ander goeters net nie belangrik nie. Daar is belangriker dinge in die lewe."/ "All of a sudden other stuff is not as important. There are more important things in life."

"nie meer krag en genade vir verspottigheid en vir kleinlikheid nie"/ "don't have the energy and grace for silliness and pettiness "

All eight participants confirmed that the breast cancer diagnosis and treatment impacted on their personality. Some felt that they started focusing more on the important things in life. The realisation of mortality heightens self-awareness, which leads people to develop courage, strength and self-expression (Carpenter, Brockopp & Andrykowski, 1999:1405-1406). These changes are supported by research which found that, after a period of contemplation, people are able to make positive lifestyle shifts within family values and priorities in life (Semple & McCance, 2010:1286).

Other participants felt that breast cancer made them more emotional people:

"raak depressief"/ "get depressed"

"sagte persoon en 'n emosionele persoon"/ "soft person and an emotional person"

"bietjie meer emosioneel"/ "a bit more emotional"

Some participants experienced the emotional change as positive, but there was one participant who saw this shift in a negative light and stated that she feels "morose". Cancer can bring about personal growth such as appreciating the small things in life, being able to see positive things in negative experiences, being less critical towards others and realising what is important in life (Venter, 2008:24). Changes in personality can mean that there are changes in how a person perceives his/her roles or chooses to fulfil those roles.

Sub-theme 2.2: Feeling like a woman

All the participants felt that they were still women throughout the process of cancer treatment and that the diagnosis and treatment didn't change their identity as women.

["dit (borskanker) het glad nie my, my vroulikheid aangetas nie"]/ "it (breast cancer) did not affect my, my femininity at all"

["['n] vrou is soos 'n porseleinpop ... ek dink ek is nou 'n beter porseleinpop"]/ "[a] woman is like a porcelain doll...I think I'm a better porcelain doll now"

["voel meer soos 'n vrou "]/ "feel more like a woman "

The findings of this study are contrary to those of other studies that depict the loss of femininity and sexuality experienced by women who lose their breasts because of breast cancer intervention (Klaeson & Berterö, 2008:188; Skrzypulec et al., 2008:614). To the question "What is a woman?" one participant stated very adamantly "definitief nie net twee tieties nie"/"definitely not just two breasts." Because the participants did not experience a change in their identity as women, the cancer did not change their fulfilment of roles linked with being women.

Sub-theme 2.3: Changes in spiritual aspects

Seven of the eight participants belong to the Christian faith and felt a change in their spiritual lives. One participant is not of the Christian faith; she stated that she is spiritual but did not experience any change in the spiritual aspect of her life.

["betoon meer dankbaarheid"]/ "show more thankfulness"

["my geloof het baie sterker geword"]/ "my faith became a lot stronger"

["verdieping in my geestelike aspek ... op 'n ander geestelike vlak"]/ "deepening in my spiritual aspect . on another spiritual level"

One of the participants stated that, even when she is fighting with God, this was also part of growing in her spiritual life.

["'n Mens het nou maar bietjie nader gegaan en jy weet, vra hoekom, jy weet, en baklei ... ek het baklei met die Here."]/ "A person does go closer and, you know, ask why, you know, and fighting...I did fight with the Lord."

Another participant felt that the spiritual aspects were an important part of coping with cancer and believes that all people need God in their lives. People can draw strength from their faith or relationship with God, which positively affects their ability to cope (Venter, 2008:27). Religious coping predicts changes in psychological adjustment in patients diagnosed with breast cancer (Gall, Guirguis-Younger, Charbonneau & Florack, 2009:1173). This is confirmed by research by Venter (2008:27-28), who found that cancer patients also expressed a deepening in their spiritual life and see religion as a way of coping with cancer. A literature review by Lin and Bauer-Wu (2003:78) shows that positive psycho-spiritual wellbeing leads to hope and finding "meaning in life" for patients diagnosed with cancer.

Sub-theme 2.4 Changes with regard to self-image

Self-image can be affected by cancer treatments as a result of the physical impact of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Some participants experienced a change, either positive or negative while others didn't experience any changes.

["bietjie leliker geword"]/ "became a little uglier"

["...daarom dink ek het ek 'n bietjie 'n swakker selfbeeld, omdat ek nou emosioneel ook raak"]/ "...that's why I think I have a bit of a weaker self-image, because now I get emotional"

["dis 'actually' beter ... want jy voel jy't iets oorkom"]/ "it's actually better... because you feel you have conquered something"

["in ' n positiewe manier . soveel komplimente gekry oor my haarstyl...vreeslike boost gekry"]/ "in a positive way...got so many compliments about my hairstyle . got a great boost"

Some participants felt that they were uglier as a result of the side-effects of treatment, whether these were physical or emotional changes, but some felt a positive change because of the side-effects of treatment. Feelings that you've overcome something or receiving compliments from strangers influenced the participants' self-image.

Some participants' way of coping with the physical changes was wearing a wig or changing their clothes or making an effort with make-up.

["Maar ek probeer nou, jy weet, my netjies aantrek... die pruik ook. Dit help jou om meer normaal te voel."]/ "But now I'm trying, you know, dress neatly...the wig as well. It helps you to feel more normal."

["pas maar net die styl van jou klere aan" ]/ "you just adjust the style of your clothes"

["Ek het net besluit ek gaan nie, ek gaan nie die pruik opsie vat nie, dit gaan my uhm, dit gaan nie vir my werk nie. Maar ek het, voor die tyd het ek sekere keuses geneem van ek gaan dan my grimering bietjie aanpas en my juweliersware en alles."]/ "I decided that I'm not, I'm not going for the wig option, it's going to make me uhm, it's not going to work for me. But I did make certain decisions beforehand, that I'm going to adjust my make-up a bit and my jewellery and everything."

Some participants expressed no changes in their self-image stating that they don't feel different.

["nee ek voel nie anderste nie "]/ "no I don't feel different"

["nogdieselfde"]/ "still the same"

What can be deduced from the sub-theme of self-image is that not everyone experiences a change in their self-image, but that if there is a negative change, there are things that can be done to a person's appearance to assist in dealing with self-image issues. This is somewhat contradictory to findings in research by DeFrank, Mehta, Stein and Baker (2007:4), which indicated that 16-54% of women reported a dislike of their body image. Because of the feelings of shame and embarrassment as well as changes in sexual functioning and intimacy that is associated with changes in body image, this is an important issue to be assessed and addressed (Kayser & Sormanti, 2002:404; Venter, 2008:26).

CONCLUSIONS

The life world of the woman entails her personality, her spirituality, her identity as a woman and her self-image. Research showed that there were changes experienced in these aspects, but that most of the changes were positive. This emphasises the participants' ability to take the positive from a negative situation.

DISCUSSION OF THEME

All participants experienced a change in their personality, most of which entailed either becoming more emotional or focusing on the important things in life. The spiritual life of participants improved and deepened, which is also an aspect of their lives that assists in coping with the cancer. Participants did not experience a change in their self-concept regarding their femininity, but some did experience a lowered self-image. Loss of hair can have a negative effect on a person's self-image, but either through wearing wigs or positive feedback from the community, this did not have a detrimental impact on the participants' self-image.

Sub-theme: Changes experienced in personality

Changes in terms of personality can also link with changes in terms of identity. Personality changes were evident in this research, where participants experienced a shift in their focus as they started to focus on the important things and no longer on trivial things. As a participant described it:

"don't sweat the small stuff."

A change in personality can cause a change in how a person perceives and choses to fulfil their roles. Research showed a change in the emotional side of participants as they became more emotional or depressed. The change of becoming more emotional was seen as a positive change by participants because it made them a "softer person" who is able to empathise with others more. Cancer diagnosis and treatment does affect a woman's personality and causes certain changes. Whether the changes are positive or negative depends on the person.

Sub-theme: Feeling like a woman

The participants in this research either felt no changes regarding their femininity or felt more like women after cancer treatment. An unchanged sense of femininity can indicate that their roles pertaining to femininity were not affected. Participants felt stronger because they had overcome something and did not feel that their femininity was linked to their breasts. It is beneficial that the participants' sense of femininity was not affected by breast cancer or even cancer treatment. Even the participants who received a lumpectomy or mastectomy didn't feel their womanhood was affected. Participants were able to distinguish their femininity from their physical appearances or the attributes that society sees as feminine (breasts and hair).

Sub-theme: Changes experienced with regard to spiritual aspects

Religion played a very important role in the participants' lives and seven out of eight participants felt that through the cancer process there was a deepening in their spirituality. Participants were able to draw on their faith for support and hope and they received support from their church. Even the participant who admitted to fighting with God about her cancer diagnosis described a deepening in her relationship with God. This aspect gave participants peace during an emotionally and physically challenging time in their lives. This research study confirms the importance of religion and how participants are able to see the "bigger picture" because of their relationship with God.

Sub-theme: Changes with regard to self-image

This sub-theme had mixed results in that some women did experience a lowered self-image, but had coping mechanisms such as wigs or a change in style, while other participants experienced an improved self-image as a result of compliments from community members, or experienced no change whatsoever. Self-image can be a sensitive issue, but these participants were able to address this issue successfully. Self-image is a subjective issue and depends on the side-effects of treatment and the individual's personality.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Depending on the side-effects of treatment and the personality of the person, certain self-image issues can become distressing for a person. Patients need to be counselled and prepared for these changes and different ways of dealing with self-image issues can be discussed. Ways of dealing with self-image issues, as found in this study, included wearing a wig or changing one's sense of fashion. During counselling it is also important to assist the patient and significant other in distinguishing between self-worth and physical appearance.

Social workers in the field of oncology should focus on preparing patients for possible personality changes and self-image changes, including ways of coping with hair loss and a mastectomy in the case of breast cancer. Seeing that spirituality is such an important aspect for patients, it will be important to ensure that they receive support from their church.

REFERENCES

ALBERTS, A.S. 2012. Knowledge beats cancer. Singapore: Marula Books. [ Links ]

ALSTON, M. & BOWLES, W. 2003. Research for social workers: an introduction to methods (2nd ed). Australia: Allen & Unwin. [ Links ]

APFFELSTAEDT, J. 2008. The status of breast health management in South Africa. [Online] Available: http://www.bizcommunity.com/article/196/335/24909.html (Accessed: 2013/07/06). [ Links ]

ASHFORD, J.B. & LECROY, C.W. 2010. Human behaviour in the social environment: a multidimensional perspective (4th ed). Belmont: Brooks/Cole, Cencage Learning. [ Links ]

BABBIE, E. 2010. The practice of social research (12th ed). Belmont: Wadsworth. [ Links ]

BARKER, R.L. 2003. The Social Work Dictionary (5th ed). Washington, DC: NASW Press. [ Links ]

BOURJOLLY, J.N., KERSON, T.S. & NUAMAH, I.F. 1999. A comparison of social functioning among black and white women with breast cancer. Social Work in Health Care, 28(3):1-20. [ Links ]

BRENNAN, J. 2004. Cancer in context: a practical guide to supportive care. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

CANSA. 2010. Breast Cancer. [Online] Available: http://www.cansa.org.za/cgi-bin/giga.cgi?cmd=causedirnews&cat=822&causeid=1056 [Accessed: 2010/09/27]. [ Links ]

CARPENTER, J.S., BROCKOPP, D.Y. & ANDRYKOWSKI, M.A. 1999. Self-transformation as a factor in the self-esteem and well-being of breast cancer survivors. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 29(6):1402-1411. [ Links ]

CHEVILLE, A.L., TROXEL, A.B., BASFORD, J.R. & KORNBLITH, A.B. 2008. Prevalence and treatment patterns in physical impairments in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26(16):2621-2629. [ Links ]

DEFRANK, J.T., MEHTA, C.C.B., STEIN, K.D. & BAKER, F. 2007. Image dissatisfaction in cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 34(3):1-6. [ Links ]

DIEKMAN, A.B. 2007. Roles and role theory. Encyclopedia of Social Psychology, 2:762-764. [ Links ]

EDWARDS, B. & CLARKE, V. 2004. The psychological impact of cancer diagnosis on families: the influence of family functioning and patients' illness characteristics on depression and anxiety. Psycho-Oncology, 13:562-576. [ Links ]

ENGEL-HILLS, P. 1995. Radiation therapy. In: PERVAN, V., COHEN, L.H. & JAFTHA, T. (eds), Oncology for health-care professionals. Kenwyn: Juta. [ Links ]

FITCH, M.I., BUNSTON, T. & ELLIOT, M. 1999. When mom's sick: changes in a mother's role and in the family after her diagnosis of cancer. Cancer Nursing. [Online] Available: http://0-ovidsp.tx.ovid.com.innopac.up.ac.za/sp-3.8.1a/ovidweb.cgi?&S=NEBMFPINAJDDECNBNCOKNEJCDCPPAA00&Link+Set=S.sh.18.19.23.27%7c11%7csl11143804 [Accessed: 2013/07/08]. [ Links ]

FLICK, U. 2000. Design and process in qualitative research. In: FLICK, U. (ed), VON KARDORFF, E. & STEIMKE, I. A companion to qualitative research. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

FOUCHÉ, C.B. 2005. Qualitative research designs. In: DE VOS, A.S. (ed), STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. Research at grass roots: for the social sciences and human service professions (3rd ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

GALL, T.L., GUIRGUIS-YOUNGER, M., CHARBONNEAU, C. & FLORACK, P. 2009. The trajectory of religious coping across time in response to the diagnosis of breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 18:1165-1178. [ Links ]

GIULIANO, A.E. & HURVITS, S.A. 2013. Breast disorders. In: PAPADAKIS, M.A. & McPHEE, S.J. (eds), Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment 2013 (52nd ed). The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. [Online] Available: http://0-accessmedicine.com.innopac.up.ac.za/content.aspx?aid=8538 [Accessed: 2013/06/24]. [ Links ]

GREEFF, M. 2011. Information collection: interviewing. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds), Research at grass roots: for the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

HUNT, K.K., NEWMAN, L.A., COPELAND, E.M. & BLAND, K.I. 2010. The breast. In: BURNICARDI, F.C., ANDERSEN, D.K., BILLIAR, T.R., DUNN, D.L., HUNTER, J.G., MATTHEWS, J.B. & POLLOCK, R.E. (eds), Schwartz's Principles of Surgery. (9th ed). The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. [Online] Available: http://0-accessmedicine.com.innopac.up.ac.za/content.aspx?aid=5021163 [Accessed: 2013/06/24]. [ Links ]

JAFTHA, T. & BRAINERS, J. 1995. Surgery. In: PERVAN, V. (ed), COHEN, L.H. & JAFTHA, T., Oncology for health-care professionals. Kenwyn: Juta. [ Links ]

KAYSER, K. & SORMANTI, M. 2002. A follow-up study of women with cancer: their psychosocial well-being and close relationships. Social Work and Mental Health, 35:391-406. [ Links ]

KIMBERLEY, D. & OSMOND, L. 2011. Role theory and concepts applied to personal and social change in social work treatment. In: TURNER, F.J. (ed), Social Work Treatment: interlocking theoretical approaches (5th ed). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

KIMMICK, G.G. & MUSS, H.B. 2009. Breast disease. In: HALTER, J.B., OUSLANDER, J.G., TINETTI, M.E., STUDENTSKI, S., HIGH, K.P. & ASTHANA, S. (eds), Hazzard's Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology (6th ed). The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. [Online] Available: http://0-accessmedicine.com.innopac.up.ac.za/content.aspx?aid=5129678 [Accessed: 2013/06/24]. [ Links ]

KLAESON, K. & BERTERÖ, C.M. 2008. Sexual identity following breast cancer treatments in premenopausal women. International Journal of Qualitative studies on Health and Well-being, 3:185-192. [ Links ]

KRALIK, D., BROWN, M. & KOCH, T. 2001. Women's experiences of 'being diagnosed' with a long-term illness. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33(5):594-602. [ Links ]

KULIK, L. & KRONFELD, M. 2005. Adjustment to breast cancer: the contribution of resources and causal attributions regarding the illness. Social Work in Health Care, 41(2):37-57. [ Links ]

LEON, E., DE JAGER, S. & TOOP, J. 1995. Chemotherapy. In: PERVAN, V., COHEN, L.H. & JAFTHA, T. (eds). Oncology for health-care professionals. Kenwyn: Juta. [ Links ]

LIN, H.R. & BAUER-WU, S.M. 2003. Psycho-spiritual well-being in patients with advanced cancer: an integrative review of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 44(1):69-80. [ Links ]

LIPPMAN, M.E. 2012. Breast cancer. In: LONGO, D.L., FAUCI, A.S., KASPER, D.L., HAUSER, S.L., JAMESON, J.L. & LOSCALZO, J. (eds), Harrison's Online (8th ed). McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. [Online] Available: http://0-accessmedicine.com.innopac.up.ac.za/resourceTOC.aspx?resourceID=4 [Accessed: 2013/06/24]. [ Links ]

LITTLE, M., PAUL, K., JORDENS, C.F.C. & SAYERS, E.J. 2002. Survivorship and discourse of identity. Psycho-Oncology, 11:170-178. [ Links ]

LO CASTRO, A.M. & SCHLEBUSCH, L. 2006. The measurement of stress in breast cancer patients. South African Journal of Psychology, 36(4):762-779. [ Links ]

LONGO, D.L. 2012. Approach to the patient with cancer. In: LONGO, D.L. (ed), FAUCI, A.S., KASPER, D.L., HAUSER, S.L., JAMESON, J.L. & LOSCALZO, J. Harrison's Online (8th ed). McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. [Online] Available: http://0-accessmedicine.com.innopac.up.ac.za/content.aspx?aid=9114033 [Accessed: 2013/06/24]. [ Links ]

LUOMA, M.L. & HAKAMIES-BLOMQVIST, L. 2004. The meaning of quality of life in patients being treated for advanced breast cancer: a qualitative study. Psycho-Oncology, 13:729-739. [ Links ]

MERIC-BENSTAM, F. & POLLOCK, R.E. 2010. Oncology. In: BURNICARDI, F.C., ANDERSEN, D.K., BILLIAR, T.R., DUNN, D.L., HUNTER, J.G., MATTHEWS, J.B. & POLLOCK, R.E. (eds), Schwartz's Principles of Surgery (9th ed). The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. [Online] Available: http://0-accessmedicine.com.innopac.up.ac.za/content.aspx?aid=5021163 [Accessed: 2013/06/24]. [ Links ]

MONTAZERI, A., VAHDANINIA, M., HARIRCHI, I., EBRAHIMI, M., KHALEGHI, F. & JARVANDI, S. 2008. Quality of life in patients with breast cancer before and after diagnosis: an eighteen months follow-up study. BMC Cancer, 8:330. [ Links ]

MONTGOMERY, M. & McCRONE, S.H. 2010. Psychological distress associated with the diagnostic phase for suspected breast cancer: systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(11):2372-2390. [ Links ]

NEW SOCIAL WORK DICTIONARY. 1995. Terminology Committee of Social Work. (eds). Cape Town: CTP Bookprinters (Pty) Ltd. [ Links ]

NIEUWENHUIS, J. 2007a. Qualitative research design and data gathering techniques. In: MAREE, K. (ed), First steps in research. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

NIEUWENHUIS, J. 2007b. Analysing qualitative data. In: MAREE, K. (ed), First steps in research. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

OXFORD CONCISE MEDICAL DICTIONARY. 2010. (5th ed). Oxford: University Press. [ Links ]

PERVAN, V., COHEN, L.H. & JAFTHA, T. 1995. Oncology: for health-care professionals. Cape Town: Juta & Co. [ Links ]

REES, G. 2004. Understanding cancer. Dorset: Family Doctor Publications. [ Links ]

ROSS, E. & DEVERELL, A. 2004. Psychosocial approaches to health, illness and disability: a reader for health care professionals. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

ROSS, E. & DEVERELL, A. 2010. Health, illness and disability: psychosocial approaches (2nd ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

ROYSE, D. 2011. Research methods in social work (6th ed). Brooks/Cole: Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

SAUSVILLE, E.A. & LONGO, D.L. 2012. Principles of cancer treatment. In: LONGO, D.L., FAUCI, A.S., KASPER, D.L., HAUSER, S.L., JAMESON, J.L. & LOSCALZO, J. (eds), Harrison's Online (8th ed). McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. [Online] Available: http://0-accessmedicine.com.innopac.up.ac.za/resourceTOC.aspx?resourceID=4 [Accessed 2013/06/24]. [ Links ]

SCHURINK, W., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DE VOS, A.S. 2011. Qualitative data analysis and interpretation. In: DE VOS, A.S. (ed), STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L., Research at grass roots: for the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

SEMPLE, C.J. & McCANCE, T. 2010. Experience of parents with head and neck cancer who are caring for young children. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(6):1280-1290. [ Links ]

SKRZYPULEC, V., TOBOR, E., DROSDZOL, A. & NOWOSIELSKI, K. 2008. Biopsychosocial functioning of women after mastectomy. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18:613-619. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN MEDICAL RESEARCH COUNCIL. 2010. What are the top causes of death due to cancer in SA? [Online] Available: http://www.mrc.ac.za//bod/faqcancer.htm [Accessed: 2011/07/25]. [ Links ]

TODRES, L. 2005. Clarifying the life-world: descriptive phenomenology. In: Holloway, I. (ed), Qualitative research in health care. McGraw Hill: Open University Press. [ Links ]

VENTER, M. 2008. Cancer patients' illness experiences during a group intervention. Potchefstroom: North West University. (MA Dissertation) [ Links ]

WERNER-LIN, A. & BIANK, N.M. 2006. Oncology social work. In: GEHLERT, S. & BROWNE, T.A. (eds), Handbook of Health Social Work. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [ Links ]

WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION. 2008. Are the number of cancer cases increasing or decreasing in the world? [Online] Available: http://www.who.int/features/qa/15/en/ondex.html [Accessed: 2013/06/11]. [ Links ]

WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION. 2012. Cancer prevention and control. Available: http://www.afro.who.int/en/clusters-a-programmes/dpc/non-communicable-diseases-managementndm/programme-components/cancer.html [Accessed 2013/06/11]. [ Links ]

WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION. 2013a. Cancer. [Online] Available: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factshets/fs297/en/index.html [Accessed: 2013/06/11]. [ Links ]

WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION. 2013b. Breast cancer: prevention and control. [Online] Available: http://www.who.int/cancer/detection/breastcancer/en/index.html [Accessed: 2013/06/11]. [ Links ]