Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Agricultural Extension

On-line version ISSN 2413-3221Print version ISSN 0301-603X

S Afr. Jnl. Agric. Ext. vol.53 n.3 Pretoria 2025

https://doi.org/10.17159/2413-3221/2025/v53n3a19230

ARTICLES

Farmer's Perception and Adoption of Digital Technologies as Information Sources for Farming Activities in the City of Tshwane, Gauteng

Mogashane C.I; Loki O.II; Mazwane S.III

IStudent, Department of Agricultural Economics, Extension and Rural Development, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, chantellemogashane2@gmail.com ORCiD number: 0009-0005-8834-0304

IILecturer, Department of Agricultural Economics, Extension and Rural Development, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, o.loki@up.ac.za Tel: 012 420 3249 ORCiD number: 0000-0003-4187-3345

IIILecturer, School of Agricultural Sciences, University of Mpumalanga, Mbombela, South Africa. Sukoluhle.mazwane@ump.ac.za. Tel: 012 002 0256. ORCHID: 0000-0001-6118-1253

ABSTRACT

Smallholder farmers are challenged by limited resources, finances, and access to complex production technologies, which hinder the implementation of good production practices such as good seed selection, knowing when to plant and harvest, pest and disease control, and access to lucrative markets. This paper used quantitative research methods to explore smallholder farmers' perceptions, adoptions, and differences in agricultural incomes between adopting and non-adopting farmers. This study reveals that smallholder farmers perceive access to real-time information as important; however, adopting digital technologies as information sources is still considered low. Binary regression analysis further revealed that the access to extension services variable positively correlated with adopting the internet (web pages), YouTube and Farmers Weekly website as information sources. Digital technologies were generally perceived to be reliable, time-effective, and easy to use; however, adopting these technologies had no significant impact on the farmer's agricultural income. This paper concludes that digital technology adoption is still considerably low; however, more and more farmers are not only open to adopting these technologies, but those who have adopted prefer incorporating them among sources they use to acquire farming information. Using digital technologies did not cause differences in agricultural income for these farmers. This study recommends public-private partnerships and community engagement through cooperatives to further drive technology adoption, fostering market access and improving livelihoods for smallholder farmers.

Keywords: Smallholder Farmer, Perception, Adoption, Digital Technology.

1. BACKGROUND

Smallholder farmers are challenged by limited resources, finances, and access to complex production technologies, which hinder the implementation of good production practices such as good seed selection, planting and harvesting timing, pest and disease control as well as access to markets (Nwafor et al., 2020; Autio et al., 2021). Accessing markets gives farmers various opportunities, such as crop diversification, reasonable input costs, increased profits, and the ability to contribute to food security. Phiri et al. (2019) argue that accessing information that is accurate and reliable can assist in overcoming some of the above challenges. Studies by Mutero et al. (2016) and Abdulai and Fraser (2023) assert that smallholder farmers in Africa still have limited access to digital technologies. There are further reports by Lwoga et al. (2011) and Ndilowe (2013) that many farmers in developing countries still rely on traditional information sources such as extension visits, and their primary digitisation sources include print media, television, and radio. Afful and Lategan (2014), Ghosh (2012), Hlatshwayo and Worth (2016), and World Bank (2010) report that in South Africa, the reduced government capital investment into extension services has negatively impacted service delivery, aggravated increases in the extension officer to farmer ratio and limited the supply of inputs and relevant agricultural information. These factors directly contribute to the overall performance of smallholder farmers who rely greatly on these services. Akintude and Oladele (2019) further report that the problem with the extension services system is the failure to keep pace with new developments and technologies to acquire and disseminate information to farmers before it becomes outdated, leaving the farmers greatly disadvantaged.

There's progress in research (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2017; Muema et al., 2018) presenting opportunities for using digital technologies in agricultural production and marketing, as well as several studies that disseminate how smallholder farmers rely on agricultural information for reliable quality food production and access to lucrative markets however, smallholder farmers are still unable to make technical and informed marketing and production decisions, they are still challenged with accessing markets and the promising impacts of integrating digital technologies in smallholder farming development have not materialised (Deichmann et al., 2016; Okello et al., 2020). According to Mushi et al. (2022), smallholder farmers still miss out on development and commercialising opportunities by not acquiring food production-related information and market information that plays a significant role in accessing competitive markets, scaling up and being an active catalyst in ensuring food security. This is despite an increase in smallholder farmers owning ICT tools such as mobile phones and computers and being aware of various digital technologies that can be used as sources of information from these tools (Phiri et al., 2019; Nwafor et al., 2020). Abdulai (2023) further reported that the adoption of these technologies is exponentially low among these farmers, especially in developing countries. The objectives of this paper are to;

a) Assess smallholder perceptions of digital technologies as sources of information for farming activities.

b) Determine the factors influencing the adoption of digital technologies as sources of information for farming activities.

c) Assess differences in agricultural incomes between digital technology-adopting and non-adopting farmers.

2. SOCIOECONOMIC FACTORS INFLUENCING THE USE OF DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIES

Various factors constitute how an individual perceives an object or subject. These include the nature of the object, the subject, the environment, and the situation where the perceiver makes the perception. For the perceiver, the characteristics could be personal interests, expectations, self-concept, and attitudes. Rogers (2004) posited that five stages influence the adoption of new technologies in the innovations theory. These stages are economic profitability, compatibility, trialability, complexity, and observability. For the adoption of new technology by farmers, Bayih et al. (2022) denote that factors such as cultural acceptability, beneficial attributes of using the technology, farmers' perception of the technology after observation, the effectiveness of the technology after its trial, and the economic status of the farmer influence technological adoption.

Singh et al. (2021) argued and concluded that infrastructural development, geography, type, and agro-climatic state of the land influence farmers' adoption of new technologies. Furthermore, he stated that the farming systems farmers use also influence adoption. The conclusion was derived from surveys of 200 rural farmers in four different agro-climates in India. Aker et al. (2005) analysed the adoption of computers for farming practices using a Tobit model to establish factors influencing the rate of technology adoption among 449 farmers in the United States. The analyses depicted that the educational levels of farmers and the age group of 30-40 years influenced the rate at which digital agricultural technologies are adopted. In corroboration, Mdoda (2017) denotes that farmers' ability to process information from varied information sources relies greatly on their level of education. Several studies (Lawal et al., 2017; Mtega et al., 2016) also denote that the age of farmers has a paramount influence on farmers accessing agricultural information and depict that male farmers over 35 years have greater access to agricultural information when compared to younger farmers. When the adoption of digital technology by smallholder maize farmers was studied in Nigeria, it was shown other factors, such as attributes of the technology to be adopted and the attributes of the farm, directly influence the adoption decision (Mwangi & Kariuki, 2015; Sennuga et al., 2020).

3. METHODS AND PROCEDURES

3.1. Description of Study Area

This study occurred in the City of Tshwane district municipality in Pretoria, which is situated in the North of the Gauteng province of South Africa. This municipality consists of 107 wards and covers an area of 6 298 km2. Compared to all the other municipalities in the province, this municipality accounts for most smallholder farmers. This is because this municipality is attributed to a high agricultural area in Region 7 (Bronkhorstspruit) and Region 5 (Cullinan), which exhibits the best soil qualities for thriving agricultural productions (Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development, 2021; Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs, 2020).

3.2. Sampling Procedure and Sample Size

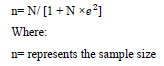

Smallholder farmers in the City of Tshwane municipality were targeted as the population of this study to conduct the intended objectives effectively. A quantitative approach was used to collect and analyse data. Semi-structured interviews and questionnaires were employed to collect data. A multi-sampling consisting of a systematic and snowballing sampling method was used on the 117 sample size, which was acquired using Slovin's formula.

Because this study used a systemic sampling technique, a sampling interval of 4 was used.

3.3. Data Analysis

This section of the paper gives insights into the quantitative tools used to analyse the collected data. Firstly, descriptive statistics in frequencies, percentages and mean values were used to characterise smallholder farmers demographically and socioeconomically. Descriptive statistics were also used to explore perceptions of digital technologies. The predictive modelling tool of a binary regression was used to model the relationship between the set of independent variables, which are the socioeconomic factors of smallholder farmers and the dependent variable, which is diverse and is modelled as a logit of p that represents a probability of the dependant variable which are perceptions and adoption taking a value of 1 (Harrell & Harrell, 2015). An exploratory analysis was conducted, and the following statistical model was used, followed by a likelihood test. An analysis used R Studio to test the hypotheses of this study. The following equation was used for the regression model.

Where ρ represents the probability that y = 1 given x. The y represents the dependent variable, which is the various digital technologies. x1, x2,...xk represent independent variables, which are the farmer's characteristics, such as age, gender, level of education, farming years, type of farm, access to extension services, and government support. b0,b1,...bk are the parameters of the model.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This section reports findings and explains the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of smallholder farmers in the City of Tshwane municipality regions and empirical results that address this study's objectives.

4.1. Characteristics of Smallholder Farmers

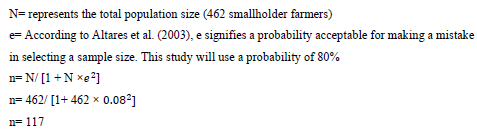

This section explains characteristics such as farmer age, gender, educational level, marital status, household size, and farming purpose, which are represented by frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviation in Table 2.

Smallholder farming in these regions is accounted for by females with a dispersion of 53.8% to 46.2% of female to male ratio; this finding corroborates various socioeconomic-centric surveys (General Household Survey, 2016; DAFF, 2016; StatsSA, 2017) which delineate that the South African smallholder farming sector is predominately female-dominated. This sector is dominated by middle-aged farmers, with the 35-45 age group accounting for the majority (36.2%) of the smallholders. Most (94.8%) of these smallholder farmers are considered literate as they have some education. This indicates that farmers can comprehend information related to their farming activities, which agrees with the sentiments of Oyewole and Sennunga (2020) that education is an important factor in adopting innovative farming techniques. The average size per household is six members, which is also posited as the source of labour on their farms (Yusuf, 2018). The smallholder farming sector in these regions is predominated by crop farmers (56.6%), with only 35.4% of livestock farmers and 8% of mixed farmers. This supports characterising statements that the regions in the municipality of Tshwane display exceptional soil qualities that are excellent for crop production (DALRRD, 2021; Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs, 2020). These farmers also stated that they do not have any income outside of their agricultural income. This contradicts the WRC report by Manona et al. (2023), which states that smallholder farmers rely on other income streams independent of their farming activities. When asked about the challenges encountered in their farming activities, 33% of the smallholder farmers state that finances pose the biggest constraints in their farming activities. These findings are consistent with Loki et al. (2023), who state that financial support was among the biggest challenges encountered by smallholder farmers.

4.2. Extension Services and Technology Use

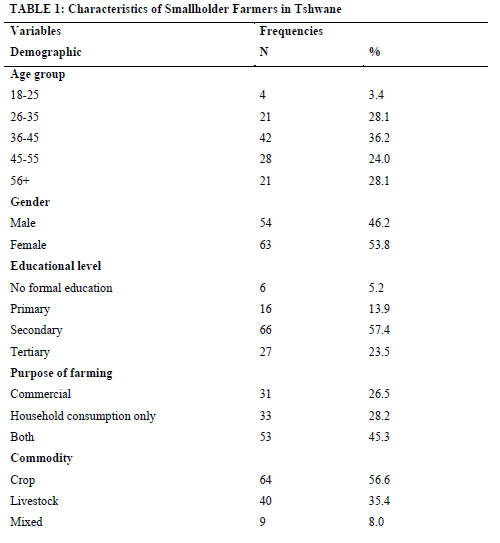

This section explores technology use, government support and extension services in the City of Tshwane regions, focusing on their availability, utilisation and general perceptions of them by smallholder farmers in these regions.

Table 3 shows that 27.7% of smallholder farmers in this region receive support from the government in their farming activities, which is in line with the report by Aliber and Hall (2012), which displayed limited government support for smallholder farmers. Nyaga et al. (2021) and FAO (2022) state that the lack of government support contributes to the uneven access and adoption of digital technologies. As shown in Table 3, 60% of the farmers know the extension services to be utilised for their farming needs. Awareness positions these farmers at a better chance of accessing extension services. Mgbenka et al. (2015) report a general lack of extension service awareness among smallholder farmers, which stems from the farmers' illiterate nature and causes a lag in the adoption of technologies. Despite the raging awareness, only 38% of the smallholder farmers have access to these services. This contradicts Loki and Mdoda's (2023) survey, which showed that 78% of smallholder farmers in the Eastern Cape had access to extension services. Extension services delivery was negatively impacted in South Africa during and after the COVID-19 outbreak due to face-to-face communication, which compromised smallholder farmers' access to information (Karubanga et al., 2016; Yusuf et al., 2022). When it comes to sharing farming information, 91.1% of smallholder farmers found extension officers to be helpful, which concurs with the findings of Loki and Mdoda (2023) that extension officers are beneficial in the dissemination of information that is relevant to their farming activities and helps keep them informed.

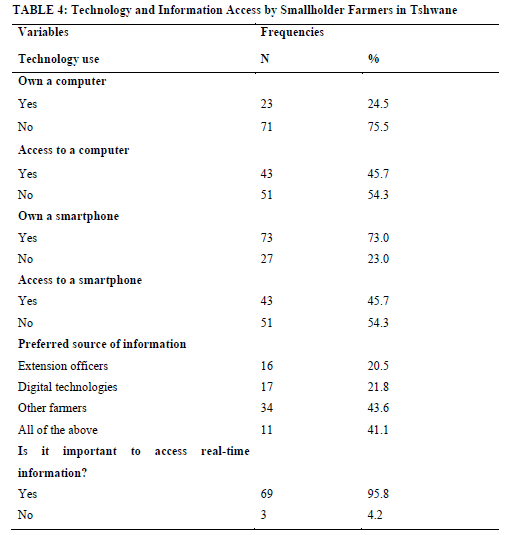

Regarding technology use, Table 4 displays that most smallholder farmers (75.5%) do not own computers, and 54.3% do not have access to a computer. However, 73% of smallholder farmers own a smartphone, and 71.8% of these farmers have access to a smartphone. This finding supports the results of Abdulai (2023) that these types of farmers have access to digital devices that are generally considered simple, such as mobile phones, as a bridge to accessing digital resources. The results of this study show that 43.6% of the farmers prefer using other farmers to acquire information. These farmers stated this preference is because of the people they know and trust. In line with this finding, a European study by Kernecker et al. (2020) shows that peer-to-peer communication is the preferred source of information for smallholder farmers. 21.8% prefer digital technologies due to their readily available and time-effective characteristics.

In comparison, 20.5% of the farmers prefer acquiring information from extension officers because they are experienced, trained and qualified to disseminate agricultural information effectively. Lastly, 41.1% of the smallholder farmers state that they prefer all of the above-mentioned information sources. This means that farmers who rely on other farmers and extension officers for information also consult digital technologies, representing a positive change in the use of these technologies for information acquisition. This finding is consistent with views by Mavhunduse and Holmner (2019) that adopting digital technologies should enhance the traditional methods of disseminating agricultural information. 95.8% of smallholder farmers state that it is important to access real-time farming information, a positive perception for smallholder farmers, as their development relies greatly on real-time agricultural information.

4.3. Perceptions of Digital Technologies as Information Sources

Smallholder farmers were asked to state their perceptions of digital technologies as information uses using a Likert-scale questionnaire. The tool ranged from 1 being "Strongly agree" to 5 being "Strongly disagree".

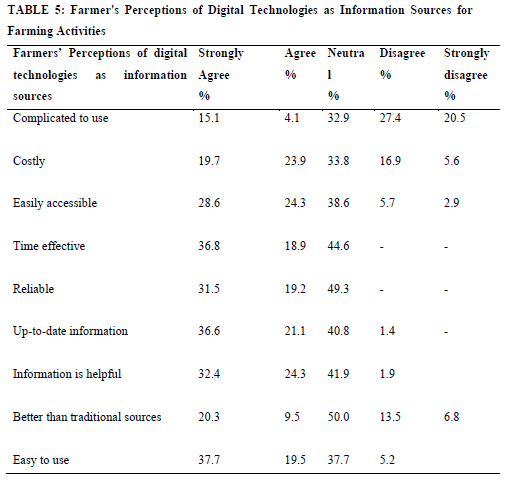

The results in Table 5 show that the common and persistent perception rated on the scale by the farmers is "Neutral" which could indicate that these farmers have limited knowledge of these technologies, nor have they adopted them. Consistent with this finding, Kernecker et al. (2020) state that farmers' perceptions of technologies are mainly informed by their lived experiences of using those technologies. 15.1% of the farmers strongly agree that digital technologies are complicated to use, 32.9% are neutral, and 27.4% strongly disagree. Regarding the economic aspect, 23.9% of the farmers' state that digital technologies are costly, while 16.9% disagree. This result is consistent with that of Hoang and Tran (2023), which depicts that most smallholder farmers in their study perceived the acquisition and utilisation of digital technologies as costly. Similarly, a study in the Eastern Cape by Bontsa (2023) reported that most of their studied population perceived the adoption of digital technologies as expensive compared to all the other technologies.

Table 5 shows that 28.6% of the farmers strongly agree that digital technologies are easily accessible, while 36.8% also strongly agree that these technologies are time-effective. Pishnyak and Khalina (2021) show that farmers' perceived effectiveness of digital technologies puts them in a better position to adopt them. Digital technologies are considered easy to use by 31.5%, who strongly agree that they are reliable sources of information for 37.7% of farmers. Caffaro et al. (2020) highlight farmers perceiving digital technologies as helpful, reliable, easy to use and prone to adoption. The information acquired from digital technologies is perceived to be up-to-date and helpful by 36.6%, and 32.4% of smallholder farmers strongly agree. When comparing digital technologies as information sources to traditional sources, 20.3% of the farmers strongly agree that they are better, the majority (50%) are neutral, and only 6.8% strongly disagree. Most farmers (37.7%) strongly agree that digital technologies are easy to use, with 19.5% stating that they agree. Hoang and Tran (2023) found that most smallholder farmers in their study perceive digital technologies as difficult to use, stemming from the perceived lack of training on digital technologies. These farmers' perceptions were generally positive, which indicates a potential openness and willingness to adopt digital technologies as information sources. This finding contradicts that of Banga et al. (2020), which states that smallholder farmers in Africa perceive digital technologies as risky, resulting in hesitation and unwillingness to adopt them. Because of this, exploring farmers' perceptions to establish their impact on adoption patterns is crucial.

4.4. Adoption of Digital Technologies as Information Sources

This section reports on findings that will assess farmers' adoption of digital technologies as information sources and the impact of digital technologies on agricultural income.

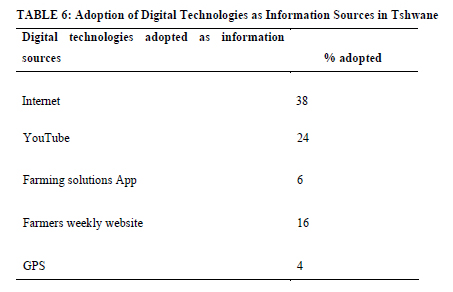

When the adoption of digital technologies as information sources was assessed, only 26% of smallholder farmers stated they had adopted some type of digital technology, such as social media, as a source of information. This finding corroborates reporting by Abdulai (2023) that smallholder farmers' adoption of digital technologies in developing countries is exponentially low. Engâs et al. (2023) state that the digital divide propels the low adoption levels of digital technologies. When the technologies were analysed independently, the most commonly adopted digital technology as an information source is the Internet at 38%. A similar study in Vietnam by Hoang and Tran (2023) found that the Internet and wireless connectivity accounted for most of the adoption with 80.9% of cases. In Rwanda, McCampbell et al. (2023) reported that this type of digital technology was only adopted by 10% of the banana farmers, which contradicts this study. Nie et al. (2021) highlighted the positive effect of using the Internet on the general well-being of farmers and their households. The adoption of YouTube was the second most commonly adopted technology at 24%, preceded by 16% of farmers' weekly adoption. YouTube is reported to be among the social platforms that can be used to disseminate agricultural information and propagate extension services and activities to broadened clientele (Kipkurgat, Onyiego & Chemwaina, 2016; Saravanan & Suchiradipta, 2017; Barau & Afrad2017). Farming solutions app and GPS were the least adopted technologies among the farmers at 6% and 4%, respectively. Hoang and Tran (2023) corroborate this finding by revealing that mobile applications and digital technologies are the second and third most commonly adopted digital technologies by farmers, respectively. An American study by Schimmelpfennig et al. (2020) found that GPS was the most widely adopted technology among farmers in this region, which is inconsistent with the result of this study.

4.5. Effect of Socioeconomic Factors on the Adoption of Digital Technologies

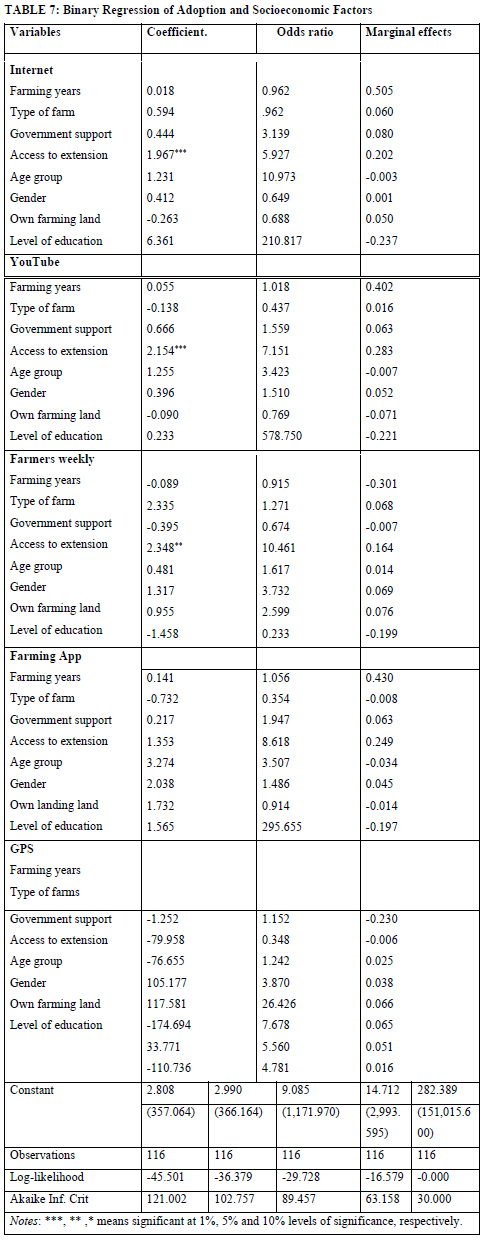

To examine the influence of socioeconomic factors modelled as independent variables on the adoption of digital technologies presented as dependent variables, a regression was conducted, and a chi-square test was used to model the significance of the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. Table 7 depicts that only three of the five outcomes had a significant statistical variable relative to adopting digital technologies as information sources: access to extension services and age. Variables such as farming experience, type of farm, government support, gender and educational level had no statistical significance relative to the adoption of digital technologies. The binary regression results are presented in the table below.

Table 7 shows that only one of the eight independent variables fit on the binary model and had a statistical significance relative to adopting digital technologies as information sources: access to extension services. This variable significantly adopted digital technologies like the Internet, YouTube, and the farmers' weekly website. Variables such as farming experience, type of farm, government support, gender and educational level had no statistical significance relative to the adoption of digital technologies.

The adoption of digital technologies as information sources among smallholder farmers is significantly influenced by access to extension services, which showed a positive and statistically significant effect for the Internet, YouTube, and Farmers Weekly website, with probabilities of adoption increasing by 85%, 87.7%, and 91.2%, respectively. Factors such as farming experience, age, gender, government support, and education also demonstrated positive correlations with adopting specific digital platforms. Conversely, ownership of farming land negatively influenced the likelihood of Internet and YouTube adoption, while variables like education and farming years had mixed effects across technologies. This finding underscores the importance of extension services and individual farmer characteristics in driving technology adoption.

However, the analysis of GPS adoption revealed no statistically significant effect from the independent variables, suggesting limited influence of factors like gender, farming years, or government support. While access to extension services, age, and land ownership showed some positive correlations, their effects varied. The study highlights that despite positive perceptions of digital technologies' ease of use, reliability, and efficiency, their adoption remains uneven, with demographic and contextual factors playing crucial roles. This calls for targeted interventions, such as improving extension services and addressing land ownership and resource access barriers, to enhance technology adoption in smallholder agriculture.

4.6. Differences in Agricultural Income Between Adopting and Non-Adopting Farmers

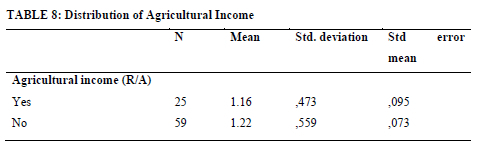

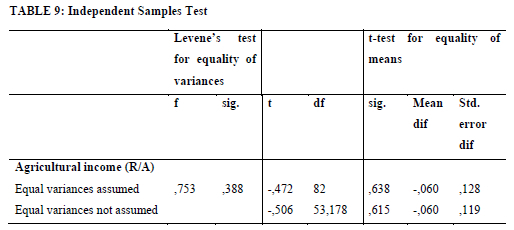

Tables 8 and 9 represent digital technologies' effect on agricultural income using results from an independent t-test.

Table 8 displays the distribution of agricultural income of adopting and non-adopting farmers. There is a difference in the mean value of the group that adopted digital technologies, which is 1.16 and the non-adopting group, with a mean of 1.22. The difference in the means is considerably smaller, with the number of the adopting group considered average compared to the non-adopting group. Despite the low adoption rates reported through various literature (Nyaga et al. 2021; Abdulai, 2023), this finding indicates that more and more smallholder farmers are adopting digital technologies as information sources. Baumüller et al. (2019) and Ndhlovu (2020) attribute this acceleration to the COVID-19 pandemic, which restricted physical interactions and climate change.

The mean difference indicates a variance between the adopting and non-adopting groups. Levene's test for equality of variances showed that equal variances are assumed, with a Ρ value of 0,388, greater than the significance level of 0.05. Therefore, the null hypothesis that the means of adopters and non-adopters are equal is accepted as there is no statistical difference between the means of the two groups.

Table 9 shows that non-adopters have a higher mean relative to the distribution of agricultural income. This finding addresses the fourth objective, which shows no difference in the agricultural incomes of smallholder farmers compared to those who have adopted digital technologies as information sources and those who have not. This finding aligns with Hoang and Tran (2023), who reported that smallholder farmers perceived a lack of real-life depiction of economic benefits from digital technologies, which would be reflected in an increase in agricultural income/productivity. Essentially, this states that smallholder farmers are still determining the economic benefits of incorporating digital technologies into their farming activities, which could make adopting these technologies a financial liability.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This study investigated smallholder farmers' perceptions, adoption rates, and the impact of digital technologies as information sources for farming activities. Farmers generally found these technologies user-friendly, reliable, and accessible, yet sometimes costly. Despite these positive perceptions, adoption of digital tools among farmers has remained low. Many farmers preferred obtaining information from fellow farmers, extension officers, and digital technologies. This preference indicates a growing openness to adopting digital tools among those who have not yet done so. However, there was no significant difference between the agricultural incomes of farmers who adopted and those who did not. The study concludes that factors beyond socioeconomic status influence technology adoption among smallholder farmers. Moreover, the adoption of digital technologies did not significantly affect agricultural income. Access to extension services was statistically significant in adopting digital tools like the Internet, YouTube, and Farmers Weekly. While extension services remain crucial for information dissemination, farmers expressed dissatisfaction with the frequency of extension visits and the quality of information shared.

6. RECOMMENDATIONS

This study recommends prioritising partnerships with tech companies and offering incentives to reduce costs and increase access to digital technologies for smallholder farmers. Peer-to-peer learning should be encouraged, allowing tech-savvy farmers to share knowledge with others. Extension officers must actively promote digital tools to bridge information gaps. Policy implications include creating supportive frameworks to improve digital infrastructure, enhance digital literacy, and provide financial support. Monitoring and evaluating technology's impact on productivity and income should inform future policies. Public-private partnerships and community engagement through cooperatives can further drive technology adoption, fostering market access and improved livelihoods for smallholder farmers.

REFERENCES

ABDULAI, A.R., BAHADUR, K.B. & FRASER, E., 2023. What factors influence the likelihood of rural farmer participation in digital agricultural services? Experience from smallholder digitalization in Northern Ghana. OutlookAgr., 52(1): 57-66. [ Links ]

AKER, J.C., HEIMAN, A., MCWILLIAMS, B. & ZILBERMAN, D., 2005. Marketing institutions, risk, and technology adoption. Preliminary Draft. Agricultural Issues Centre, University of California. [ Links ]

ALIBER, M. & HALL, R., 2012. Support for smallholder farmers in South Africa: Challenges of scale and strategy. Dev. South. Afr., 29(4): 548-562. [ Links ]

AUTIO, A., JOHANSSON, T., MOTAROKI, L., MINOIA, P. & PELLIKKA, P., 2021. Constraints for adopting climate-smart agricultural practices among smallholder farmers in Southeast Kenya. Agric. Syst., 194: 103284. [ Links ]

BARAU, A.A. & AFRAD, M.S.I., 2017. An overview of social media use in agricultural extension service delivery. J. Agric. Inf., 8(3): 50-61. [ Links ]

BARNES, A.P., SOTO, I., EORY, V., BECK, B., BALAFOUTIS, A., SÁNCHEZ, B., VANGEYTE, J., FOUNTAS, S., VAN DER WAL, T. & GÓMEZ-BARBERO, M., 2019. Exploring the adoption of precision agricultural technologies: A cross regional study of EU farmers. Land Use Policy., 80: 163-174. [ Links ]

BANGA, K., RODRIGUEZ, A.R. & TE VELDE, D.W., 2020. Digitally enabled economic transformation and poverty reduction. Available from https://set.odi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/DEET-and-poverty-reduction_final-2.pdf [ Links ]

BAYIH, A.Z., MORALES, J., ASSABIE, Y. & DE BY, R.A., 2022. Utilization of Internet of Things and Wireless Sensor Networks for Sustainable Smallholder Agriculture. Sensors., 22(9): 3273. [ Links ]

BESE, D., ZWANE, E. & CHITENI, P., 2021. Adoption of sustainable agricultural practices by smallholder farmers in Mbhashe Municipality in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Afr. J. Dev. Stud, Si(1): 11-33. [ Links ]

BONTSA, N.V., MUSHUNJE, A., NGARAVA, S. & ZHOU, L., 2023. Utilisation of Digital Technologies by Smallholder Farmers in South Africa. S Afr. Jnl. Agric. Ext., 51(4): 104-146. [ Links ]

BUKCHIN, S. & KERRET, D., 2020. Character strengths and sustainable technology adoption by smallholder farmers. Heliyon., 6(8): e04694. [ Links ]

COGGINS, S., MCCAMPBELL, M., SHARMA, A., SHARMA, R., HAEFELE, S.M., KARKI, E., HETHERINGTON, J., SMITH, J. & BROWN, B., 2022. How have smallholder farmers used digital extension tools? Developer and user voices from Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Southeast Asia. Glob Food Sec., 32: 100577. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY AND FISHERIES (DAFF)., 2016. Funds Redirected Towards Drought Relief- Ministry of Agriculture Report in Budget Vote Speech. [ Links ]

DEICHMANN, U., GOYAL, A. & MISHRA, D., 2016. Will digital technologies transform agriculture in developing countries? Agric. Econ., 47(S1): 21-33. [ Links ]

ECONOMIC REVIEW OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN AGRICULTURE., 2020. Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development, Statistics and Economic Analysis. Available from https://www.dalrrd.gov.za/Portals/0/Statistics%20and%20 [ Links ]

EVANGELISTA, R., GUERRIERI, P. & MELICIANI, V., 2014. The economic impact of digital technologies in Europe. EconInnovNew Tech., 23(8): 802-824. [ Links ]

FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANISATION (FAO)., 2017. E-agriculture in action. FAO and ITU. [ Links ]

FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANISATION (FAO)., Status of Digital Agriculture in 47 sub-Saharan African Countries. FAO and ITU. [ Links ]

HARRELL, J.R. & HARRELL, F.E., 2015. Binary logistic regression. Regression modeling strategies: With applications to linear models, logistic and ordinal regression, and survival analysis. Springer. [ Links ]

HOANG, H.G. & DRYSDALE, D., 2021. Factors affecting smallholder farmers' adoption of mobile phones for livestock and poultry marketing in Vietnam: Implications for extension strategies. Rural Ext Innov Syst., 17(1): 21-30. [ Links ]

LOKI, O. & MDODA, L., 2023. Assessing the contribution and impact of access to extension services toward sustainable livelihoods and self-reliance in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev., 23(4): 23000-23025. [ Links ]

MAVHUNDUSE, F. & HOLMNER, M.A., 2019. Utilisation of mobile phones in accessing agricultural information by smallholder farmers in Dzindi Irrigation Scheme in South Africa. Afr. J. Libr. Arch. Inform. Sci., 29(1): 93-101. [ Links ]

MDODA, L., 2017. Market participation and value chain integration among smallholder homestead and irrigated Crop farmers in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Doctoral thesis, University of Fort Hare. [ Links ]

MGBENKA, R.N., MBAH, E.N. & EZEANO, C.I., 2016. A review of smallholder farming in Nigeria: Need for transformation. J. Agric. Ext. Rural Dev. Stud., 3(2): 43-54. [ Links ]

MIINE, L.K., AKORSU, A.D., BOAMPONG, O. & BUKARI, S., 2023. Drivers and intensity of adoption of digital agricultural services by smallholder farmers in Ghana. Heliyon., 9(12). [ Links ]

MTEGA, W.P., NGOEPE, M. & DUBE, L., 2016. Factors influencing access to agricultural knowledge: The case of smallholder rice farmers in the Kilombero district of Tanzania. S. Afr. J. Inf. Manag.,, 18(1): 1-8. [ Links ]

MUEMA, E., MBURU, J., COULIBALY, J. & MUTUNE, J., 2018. Determinants of access and utilisation of seasonal climate information services among smallholder farmers in Makueni County, Kenya. Heliyon., 4(11): e00889. [ Links ]

MUSHI, G.E., DI MARZO SERUGENDO, G. & BURGI, P.Y., 2022. Digital technology and services for sustainable agriculture in Tanzania: A literature review. Sustainability., 14(4): 2415. [ Links ]

NDLAZILWANA, L.C., 2022. Perceptions, coping strategies and welfare impact of drought among small stock farmers in Amathole, Eastern Cape. Doctoral dissertation, North-West University. [ Links ]

OKELLO, J.J., KIRUI, O.K. & GITONGA, Z.M., 2020. Participation in ICT-based market information projects, smallholder farmers' commercialisation, and agricultural income effects: Findings from Kenya. DevPract., 30(8): 1043-1057. [ Links ]

PFEIFFER, J., GABRIEL, A. & GANDORFER, M., 2021. Understanding the public attitudinal acceptance of digital farming technologies: A nationwide survey in Germany. Agric Hum Values., 35(1): 107-128. [ Links ]

TEMBA, B.A., KAJUNA, F.K., PANGO, G.S. & BENARD, R., 2016. Accessibility and use of information and communication tools among farmers for improving chicken production in Morogoro municipality, Tanzania. Livestock Res Rural Dev., 28(1). [ Links ]

TULU, A., KHUSHI, Y.R. & CHALLI, D.G., 2018. Supplementary value of two Lablab purpureus cultivars and concentrate mixture to natural grass hay basal diet based on feed intake, digestibility, growth performance and net return of Horro sheep. Int. J. Livest. Prod., 9(6): 140-150. [ Links ]

WIGGINS, S. & KEATS, S., 2013. Smallholder agriculture's contribution to better nutrition. London: ODI. [ Links ]

YUSUF, S.F.G., POPOOLA, O.O. & YUSUF, F.T.O., 2022. Harnessing the use of alternative media for South Africa's agricultural extension service delivery in the face of the COVID-19 global pandemic. S Afr. Jnl. Agric. Ext., 50(2): 137-155 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

C. Mogashane

Correspondence Email: Chantellemogashane2@gmail.com