Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Animal Science

On-line version ISSN 2221-4062Print version ISSN 0375-1589

S. Afr. j. anim. sci. vol.55 n.7 Pretoria 2025

https://doi.org/10.4314/sajas.v55i7.02

C.A. ShepstoneI, #; N. van RooyenII; M.W. van RooyenII; J. du P. BothmaIII; R.E.J. BurroughsI,

IDepartment of Production Animal Studies, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

II7 St George Street, Lionviham, Somerset West, 7130, Western Cape, South Africa

III11 Orange Street, Heather Park, George, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This study aims to bridge the gap between the large stock unit method and the grazer and browser unit methods for estimating the stocking densities of wild herbivore ungulates on wildlife ranches and reserves using both extensive and intensive production methods. Animal substitution equivalents based on metabolisable energy are calculated to estimate stocking densities; however an annual up-to-date vegetation evaluation is required to estimate the carrying capacity of the habitat to support wild herbivore ungulates without it being degraded over time. This study provides an applied approach to how refined large stock, wild herbivore, grazer, and browser unit equivalents can be used effectively. The two production methods described differ in their intensity of animal management. In the extensive wild herbivore ungulate production method, the mean animal mass is used to calculate the large stock, wild herbivore, grazer, and browser substitution equivalent units, while in the intensive wild herbivore ungulate production method, the mean mass per physiological state, with varying percentages of suckling offspring, is used to do so. These methods are extrapolated from mean linear transformations of the different physiological states and sexes of the different types of herbivores. The extensive wild herbivore ungulate production method is preferred when evaluating wildlife ranches focused on hunting and tourism, as wildlife census data do not incorporate the numbers of males, females, and offspring, whereas the intensive wild herbivore ungulate production method is preferred for intensive breeding systems in which the numbers of males, females, and offspring are known.

Keywords: extensive wild herbivore ungulate production, intensive wild herbivore ungulate production, breeding system, metabolisable energy, metabolic mass, stocking rate, substitution equivalent units

Introduction

One of the fundamental questions relating to wildlife ranch or game ranch management is how many animals a given habitat can support at a particular point in time without degrading it over time (Meissner, 1982; Danckwerts & Teague, 1989; Grossman et al., 1999; Bothma et al., 2004). However, the number of animals that the habitat on a wildlife ranch/reserve can support sustainably will depend on factors such as rainfall, fire, herbivory, condition of the vegetation, and the ranch's objectives. Therefore, a clear statement of objectives is a prerequisite to formulating a veld management strategy. For example, objectives may include maximising meat production, breeding rare species or subspecies for resale, providing biltong and trophy quality animals for hunting, providing viewing and ecotourism experiences, or a combination of some or all of these objectives (Grossman et al., 1999).

Stocking densities (SD) for wild animals on wildlife ranches and reserves in southern Africa are often determined using carrying capacity (CC) norms set by agriculturalists based on grazing livestock, and are expressed as ha/large stock unit (LSU) (Meissner, 1982; Grossman et al., 1999; Bothma et al., 2004). This has led to wildlife ecologists refining SD estimates for wild herbivore ungulates by developing a method where both the grazing and browsing capacity of the habitat are incorporated into SD calculations; the resultant grazer unit (GU) and browser unit (BU) values are better able to protect the habitat from overutilisation (Peel et al., 1994, 1999; Dekker, 1997; Bothma et al., 2004). This study aims to provide an easy-to-use practical guide for agriculturalists, wildlife ecologists, wildlife ranchers, and vegetation ecologists.

The SD is the concentration of wild or domesticated herbivores on the veld and/or pasture at any moment in time and is expressed as the hectares per LSU (ha/LSU) (Trollope et al., 1990). The stocking rate (SR) is the number of animals allocated to a specific piece of land for a specified period of time and is expressed as the hectares per LSU per time period (ha/LSU/time period) (Trollope et al., 1990; Tainton et al., 1999). Although the CC is often criticised as a nebulous concept (Dhondt, 1988; Grossman et al., 1999; Del Monte-Luna et al., 2004; Sayre, 2008), it is commonly applied to extensive systems, where it is defined as the potential of an area to support livestock/wildlife through forage and/or fodder production over an extended number of years without degrading the habitat (Trollope et al., 1990). Furthermore, it is a function of the veld or pasture management applied, the trampling effects of the animals, the water point distribution, the availability and amount of edible and nutritious plants, and the existence of competitive animal behaviours. These factors all relate to food intake to varying degrees, where the food intake by the animal is determined by its energy requirements and the animal's ability to fulfil these needs by the food that it selects (Meissner, 1982). A vegetation study is, therefore, a prerequisite to assess how much edible forage (cellulolytic energy source) is available to sustain a population of herbivores. This has led to the development of models through which the CC, SD, and SR can be estimated on wildlife ranches and reserves.

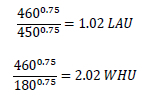

The animal units used in these models are the LSU, also known as the livestock unit (LU), the animal unit, also known as the large animal unit (LAU), the GU, and the BU. An LSU is equivalent to a steer with a body mass of 450 kg, whose body mass increases by 500 g per day, on grassland with a mean digestible energy concentration of 55%. This equates to a requirement of 75 MJ of metabolisable energy (ME) per day to maintain this growth (Meissner, 1982). The LAU, originally described by Meissner (1982), is also equivalent to a 450 kg steer with a mass increase of 500 g per day, but does not account for the animals' daily energy requirement (Van Rooyen & Bothma, 2016). The GU is equivalent to a mature 180 kg blue wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus), and the BU is equivalent to a mature 180 kg greater kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros) (Van Rooyen & Bothma, 2016).

The main difference between the animal units (specific animal equivalents) used in these methods is that the LAU, GU, and BU equivalents, which are estimated for different wild herbivore ungulates, are calculated by dividing the metabolic mass of a particular herbivore by the metabolic mass of a 450 kg steer (an LSU) or a 180 kg wild herbivore, to calculate the BU and GU (Owen-Smith, 1999; Bothma et al., 2004; Van Rooyen & Bothma 2016). In contrast, the LSU method, as proposed by Mentis & Duke (1976), Mentis (1977), Meissner (1982), and Shepstone et al. (2022), uses the ME requirement instead of the metabolic mass as its baseline, to compare the energy requirements of a poorly studied wild herbivore ungulate to that of a well-studied 450 kg steer (Bos indicus/taurus).

The calculated ME (MEC), calculated LSU (LSUC), calculated GU (GUC), calculated BU (BUC), and calculated GU/BU (GUC/BUC) equivalents described by Shepstone et al. (2022) have been replaced by the refined ME, LSU, wild herbivore unit (WHU), GU, and BU equivalents to estimate SD and SR on wildlife ranches and reserves (Shepstone et al., in press; Shepstone, in press). The ME was compared to other published research when considering the accuracy of the refined animal unit equivalents. The mean field metabolic rate of animals of low and medium activity levels compares well with the maintenance energy requirements of animals of similar mass in other published literature (Meissner, 1982; NRC, 2007; Shepstone et al., 2022) and with the values calculated using feed formulation software (Zootrition© 2.7 Software, St. Louis, USA). The field metabolic rate estimates the animal's total energy expenditure, including all primary energy costs (Costa & Maresh, 2018), and is determined by multiplying the basal metabolic rate (Heusner, 1982; Hayssen & Lacy, 1985) by an approximated value of 1.35 for low activity and 1.85 for medium activity animals (Karasov, 1992).

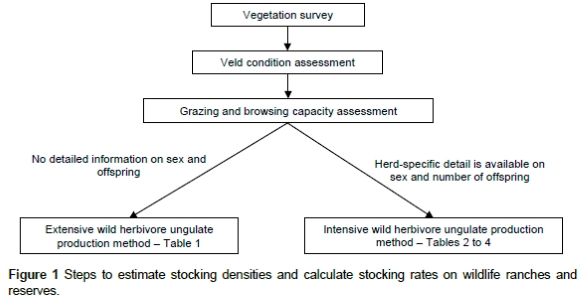

The two approaches used to estimate the SD and calculate the SR on wildlife ranches and reserves are illustrated in Figure 1. The vegetation survey, veld condition assessment, and grazing and browsing capacity calculations used in rangeland assessments are discussed in detail by several authors (Grossman et al., 1999; Bothma et al., 2004; Van Rooyen & Bothma, 2016).

The animal substitution equivalents that can be used to (a) estimate the current or future optimal SD for extensive wild herbivore production systems and (b) calculate a suitable SR for intensive wild herbivore production/breeding systems without degrading the habitat quality over time will be discussed next. Four examples in which a fixed number of animals are in the same baseline environment are used to compare the extensive and intensive wild herbivore ungulate production methods (also referred to as the extensive and intensive production methods), with and without offspring (and thus, lactating females). The intensive breeding of wildlife requires additional veterinary care and nutrition, and focuses on production parameters such as improving animal condition, calving percentage, weaning mass, horn growth, immune status, and general health (Shepstone, in press).

Materials and methods

The methods for calculating the wild herbivore SD and SR are divided into those suitable for extensive wildlife ranching, which focuses on hunting and tourism, and those suitable for intensive wildlife ranching, which focuses on breeding some or all of the wild herbivore ungulates on the ranch, either in camps or on the entire property. The data used to estimate the SD and SR, namely the mean animal mass (population mean), the mean mass as per physiological state, and the percentage of grass and browse in the population's diets, are extracted from Bothma et al. (2004), Orban (2014), and Van Rooyen & Bothma (2016).

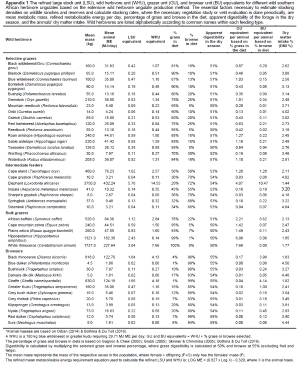

The extensive wild herbivore ungulate production method (Table 1) is used for extensive wildlife ranches and reserves focusing on hunting and tourism (Shepstone et al., in press). The mean animal mass, the LSU and WHU ME requirements in MJ ME, and the percentages of grass and browse in the diets are used to estimate the percentage of dry matter intake (DMI), refined ME, LSU, WHU, GU, and BU substitution equivalents. The animal unit substitution equivalents are extrapolated from the mean linear transformations irrespective of physiological states (Shepstone et al., 2022). Appendix 1 lists the animal substitution equivalents used to estimate the SD and SR on wildlife ranches and reserves.

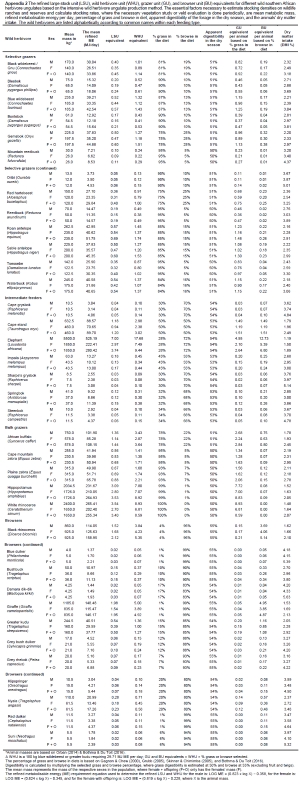

The intensive wild herbivore ungulate production method (Tables 2, 3, and 4) is used for semi-intensive or intensive wildlife ranching systems. This method incorporates the mean mass of each of the three different physiological states (male, female, and female with offspring) within the LSU and WHUs ME requirements in MJ ME for each type of herbivore. The proportion of grass and browse that a specific type of wild herbivore selects is used to estimate the refined ME, LSU, WHU, GU, and BU substitution equivalents. The animal unit substitution equivalents are extrapolated from the mean linear transformations for the different physiological states, incorporating sex (Shepstone et al., 2022) but excluding the calf/lamb component. Appendix 2 lists the animal substitution equivalents used to estimate the SD and SR on a wildlife breeding ranch.

The calculations used to show the differences between the old and newly established methods to estimate the extensive and intensive wild herbivore production method's different animal unit equivalents are as follows:

The metabolic mass method's LAU and WHU substitution equivalents for a 460 kg Cape eland (Taurotragus oryx) are 1.02 LAU and 2.02 WHU:

The extensive wild herbivore ungulate production method's calculations used to calculate a wild herbivore's daily ME requirement, and refined LSU, WHU, GU, and BU equivalents are as follows:

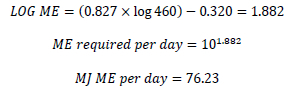

The ME requirement in MJ ME of an average Cape eland with a mean mass of approximately 460 kg is:

This is converted into refined LSU and WHU equivalents as follows:

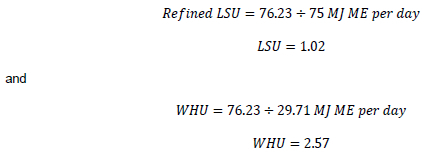

With the LSU's daily energy requirement of 75 MJ ME (Meissner, 1982) and the WHU's daily energy requirement of 29.71 MJ ME (Shepstone et al., 2022), the Cape eland will have a refined LSU equivalent of 1.02 and a WHU equivalent of 2.57 (Table 1 and Appendix 1).

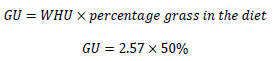

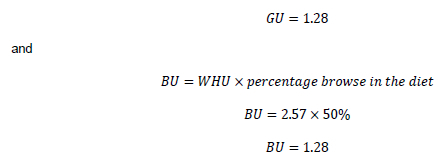

When converting this to a GU or BU, diet selection is incorporated, and the Cape eland is thus equivalent to 1.28 GU and 1.28 BU (Appendix 1).

The calculations used to calculate the daily ME requirement, and refined LSU, WHU, GU, and BU equivalents for the intensive production method are as follows:

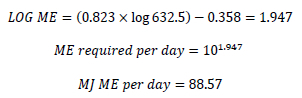

The ME requirement in MJ ME of a Cape eland bull with a mass of approximately 632.5 kg is:

This is converted to refined LSU and/or WHU values as follows:

With the LSU's daily energy requirement of 75 MJ ME (Meissner, 1982) and the WHU's daily energy requirement of 29.71 MJ ME (Shepstone et al., 2022), a Cape eland bull will have a refined LSU equivalent of 1.18 and a WHU equivalent of 2.98 (Table 2).

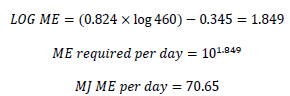

The ME requirement in MJ ME of a dry Cape eland cow with a mass of approximately 460 kg is:

This is converted to refined LSU and/or WHU values as follows:

With the LSU's daily energy requirement of 75 MJ ME (Meissner, 1982) and the WHU's daily energy requirement of 29.71 MJ ME (Shepstone et al., 2022), the dry Cape eland cow will have a refined LSU equivalent of 0.94 and a WHU equivalent of 2.38 (Table 2 and Appendix 2).

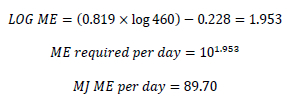

The daily ME requirement in MJ ME of a Cape eland cow with a calf with a mass of approximately 460 kg is:

This is converted to refined LSU and/or WHU values as follows:

With the LSU's daily energy requirement of 75 MJ ME (Meissner, 1982) and the WHU's daily energy requirement of 29.71 MJ ME (Shepstone et al., 2022), the Cape eland cow with a calf will have a refined LSU equivalent of 1.2 and a WHU equivalent of 3.02 (Table 2 and Appendix 2).

When calculating the WHU, GU, and BU equivalents for the intensive production method, the values for percentage graze and browse in the diet for the different physiological states listed in Appendix 2 are used.

Results

In all the examples discussed below, the following criteria are kept constant: The calculations are made for a 2000 ha wildlife ranch/reserve with a grazing capacity of 200 LSU, with 328 adult animals (Tables 1 and 2), of which 30% are bulls; however, in Tables 3 and 4, the animal numbers are greater because the offspring are added. The ranch/reserve has a grazing capacity of 10 ha/LSU and 5 ha/GU, and has a browsing capacity of 10 ha/BU. The numbers of male and female animals are also kept constant in all examples. It is also assumed in all examples that a qualified vegetation ecologist has recently conducted a vegetation study or veld evaluation to confirm the habitat's grazing and browsing capacities.

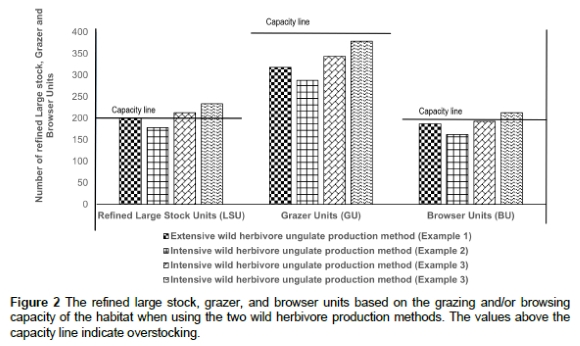

Example 1 (Table 1) describes a typical bushveld wildlife ranch/reserve where appropriate wild herbivore ungulates are present. Using the animal-specific mean mass, the mean LSU, the WHU equivalents from Appendix 1, and the percentages of grass and browse in the diet, the SD can be calculated/estimated using the extensive wild herbivore ungulate production method. In this example, the ranch/reserve would, therefore, be able to stock 200 LSU conservatively or 400 GU and 200 BU. The numbers of animal units listed in Tables 1 to 4 are the numbers that the habitat can potentially support based on the vegetation survey, and are the products of direct calculations of the size of the ranch divided by the sum of the respective LSU, WHU, and GU and BU equivalents, estimating the grazing or browsing capacity of the habitat. The numbers of LSU, WHU, GU, and BU in Tables 1 to 4 are the actual population sizes of the different wild herbivore ungulates, expressed as LSU, GU, and BU. The calculated animal unit equivalents in LSU, GU, and BU (Table 1) are as follows: the 200 LSU are equal to the vegetation study's estimated LSU, the 318 GU are less than the estimated 400 GU, and the 187 BU are less than the estimated 200 BU.

Example 2 (Table 2) describes a wildlife ranch where 20% of the 328 animals from Example 1 (Table 1) are offspring, over a fixed time period (a year). The intensive production method is used for the calculations instead of the extensive production method, because the calculations incorporate the offsprings' dams, and thus include 20% lactating females. The habitat of the ranch/reserve would be able to conservatively support 200 LSU, 400 GU, and 200 BU without being degraded. When using the grazing and browsing capacities of the intensive production method and its estimated SD (vegetation study) results (Table 2), the 178 LSU is less than the estimated SD of 200 LSU, the 288 GU is less than the estimated 400 GU, and the 182 BU is less than the estimated 200 BU.

Example 3 (Table 3) describes a wildlife ranch/reserve where 20% of the females conceive and raise their offspring over a defined period (a year). The expected 46 offspring, with a male-to-female ratio of 50:50, are added to the 328 adult animals. The 213 LSU are more than the vegetation study's estimated SD of 200 LSU. However, the 344 GU is less than the estimated SD of 400 GU, and the 193 BU is less than the estimated 200 BU.

Example 4 (Table 4) describes an intensive breeding system where at least 80% of the female animals conceive and raise their offspring. The 183 offspring with a male-to-female ratio of 50:50 are added to the 328 adult animals. In this intensively managed environment, the ranch can, conservatively, be stocked with 200 LSU, 400 GU, and 200 BU. When using the grazing and browsing capacities of the intensive wild herbivore production method and its estimated SD, the 234 LSU is greater than the estimated SR of 200 LSU based on the vegetation study, the 379 GU is less than the estimated SR of 400 GU, and the 213 BU is more than the estimated 200 BU.

Discussion

When considering the animal units used in SD, SR, and CC estimates for a ranch/reserve, it is essential to appreciate that different fields of study use different methods when calculating these parameters. Agriculturalists using the livestock approach include mass and the relevant physiological production states of the herbivores, and thus their energy requirements, while wildlife ecologists only use the mean animal mass (Shepstone et al., 2022). Furthermore, agriculturists focus on grazing livestock (Meissner, 1982; Grossman et al., 1999), while wildlife ecologists incorporate the available edible browse for browsing wild herbivores into their assessments (Peel et al., 1994, 1999; Dekker, 1997). It is important to note that the feed/forage selected and eaten by a wild herbivore ungulate is directly related to the animal's energy and other nutrient requirements (Meissner, 1982).

The main reason why it was necessary for wildlife ecologists to modify the LSU model for wild herbivores was that the LSU methodology ignored the edible portion of trees and shrubs. Most wild herbivores will select both grasses and browse as food sources (Van Rooyen & Bothma, 2016); however, some species cannot digest dry lignified plant material, making the available dry grass worthless during the dry season. These wild herbivore species will, therefore, only select grass while it is green and moist. Such species are classified as concentrate selectors (browsers), as they select the more digestible dry browse as a food source in the dry season (Hofmann, 1973; Clauss et al., 2003; Cheeke & Dierenfeld, 2010). Consequently, if a vegetation study does not incorporate the edible browse portion, the interpretation should only consider wild herbivores that can eat and digest grass in the dry season.

Over the last three decades, many livestock and wildlife ranches have converted or incorporated intensive wildlife breeding systems. This practice has led to wild herbivores being intensively ranched like livestock (Oberem & Oberem, 2016). Critical management interventions are therefore necessary to ensure that these changes are effective, particularly when calculating the SD, SR, and CC from the available forage, and stocking the ranch or reserve accordingly. The strategic feeding of balanced rations and provision of internal and external parasite control may also be necessary. The incorporation of the animals' energy requirements, through the use of the refined LSU and WHU methods, would, therefore, be preferable.

The relative animal units and methods for estimating the LAU, GU, BU, and WHU equivalents are mathematically similar, with animal mass as the common denominator. In contrast, when considering the LSU method, the animal's mass and ME requirements at a particular physiological production state are used to estimate the LSU equivalent, while the methodologies applied to replace the LSU method rely only on metabolic mass, and thus make it an unequal comparison. The derived log-log transformation equations described by Shepstone et al. (2022) provide a more accurate method for determining the relative refined ME, LSU, GU, BU, and WHU equivalents for the different wild herbivore species at different physiological production states. For a more thorough discussion of why the refined LSU, WHU, GU, and BU methods - based on metabolic energy - should replace the LAU and GU/BU methods - based on metabolic mass - see Shepstone et al. (2022).

This study illustrates an applied approach to comparing the extensive and intensive wild herbivore production methods, where the refined LSU, GU, BU, and WHU values for both methods can be used to estimate suitable SD and SRs.

It should be noted that for this calculation to work, the camps used for intensive wildlife breeding must be large enough and have enough suitable forage to sustain the wild herbivores throughout the year. The only form of supplemental feed supplied to the animals should be low-intake nutrient supplements designed to compensate for the nutrient shortfalls of the green and dry forage. This enables the animal to attain an optimal physical body condition and reach its production goals. For example, a green season mineral lick contains salt, calcium, phosphorus, and trace minerals, and a dry season supplement contains protein, energy, macro minerals, trace minerals, and vitamins.

When evaluating the veld condition of a wildlife ranch/reserve that focuses on hunting and/or tourism, the extensive wild herbivore ungulate production method and/or the intensive wild herbivore ungulate production method can be used. When comparing the extensive method described in example 1 with the intensive method described in example 2 (Table 5), the population in example 1 is only considered to be adult animals, whereas the population in example 2 consists of 40% males and 60% females, of which 20% are offspring. Therefore, the examples compare a baseline population to a more specified one (Table 5 and Figure 2). The extensive wild herbivore ungulate method was selected to reach 200 LSU, with the population illustrated in example 1 (Table 5 and Figure 2). If the intensive production method, where 20% of the population are offspring with an LSU equivalent of 178, is used, the wildlife rancher can increase the population by 22 LSU, or keep to the 200 LSU as estimated using the extensive production method.

Based on the WHU values from examples 1 and 2, the ranch's estimated grazing and browsing capacity in the vegetation study is 400 GU and 200 BU, respectively (Table 5). The populations in examples 1 and 2 indicate that the WHU population on the ranch (505 and 450 WHU, respectively) comprises 318 GU and 187 BU according to the extensive production method, and 288 GU and 162 BU according to the intensive method. These are both lower than the estimated WHU CC extrapolated from the vegetation study's 400 GU and 200 BU. Therefore, the ranch can increase its stocking density accordingly, although the size of the increase will differ (Figure 2).

Nonetheless, animal unit equivalents are, in practice, only guidelines, as most wildlife counts are done by aeroplane or helicopter and some of the animals on the reserve may hide during these counts; consequently, the actual number of animals may be more than counted. Therefore, the extensive production method is generally considered a safer option than the intensive production method. However, when the exact numbers of males, females, and offspring on the wildlife ranch/reserve are known, the intensive production method is more suitable for determining the appropriate animal numbers, based on the CC calculated from the vegetation study (examples 2-4; Table 5).

Examples 1 to 4 (Table 5) illustrate which method is suitable for estimating the CC and SD on a wildlife ranch/reserve, and demonstrate how females with suckling offspring affect the CC and SD estimates. When examples 1 to 3 are compared in terms of their LSU, the extensive production method (example 1) results in a total of 200 LSU, whereas the intensive production method used in examples 3 and 4 results in totals of 213 and 234 LSU, respectively (Table 5). The intensive production method will be more suitable in these cases because it incorporates the extra energy requirements of females with suckling offspring. However, since the LSU equivalent values exceed the CC of the ranch, these examples indicate that the ranch should destock by 13 (example 3) or 34 (example 4) LSU to prevent overstocking (Table 5).

The WHU values calculated demonstrate the same general tendency as for the calculated LSU values. The equivalent values are 344 GU and 193 BU, and 379 GU and 213 BU, in examples 3 and 4, respectively, which are generally lower than the 400 GU and 200 BU recommended based on the vegetation survey, apart from the higher BU value of 213 in example 4 (Table 5). On a wildlife ranch/reserve, the SD can be changed to reach the equivalent WHU values recommended by the vegetation survey. When interpreting the results, in terms of the LSU and WHU values, the intensive production method produces higher animal equivalent values than the extensive production method. This is because the energy requirements of females with suckling offspring are higher than those of the average animal used in the extensive production method, as lactating females require higher quality forage to satisfy their daily energy requirements to stay in a good physical body condition and produce milk.

The suckling phase and time from birth to weaning for different herbivore species must also be considered for accurate CC and SD estimates. The examples were calculated using both 20% lactating females (example 3) and 80% lactating females (example 4) so that the means could be used as the final CC and SD estimates in the evaluation. A 20% suckling offspring value, rather than a zero value, was used to ensure that younger, weaned animals were still included.

In summary, when estimating the CC or SD, it is important to decide in advance which production method will be used and whether to use the LSU or WHU values derived from the vegetation survey. The derived log-log transformation equations used for the two production methods attempt to address the management circumstances for each system, as they are more accurate for determining the ME requirements of wild herbivores in different production systems. Therefore, if the objective is to determine the SD of a wildlife ranch/reserve using the latest vegetation survey, then use the extensive production method to indicate whether the reserve/ranch is understocked, overstocked, or stocked correctly. The intensive production method will be more accurate when the vegetation survey is used as a tool to determine how many of a desired type of herbivore, such as African buffalo or sable antelope (Hippotragus niger), can be kept free-ranging or in a camp system for semi-intensive or intensive breeding purposes.

Conclusions

This study of the methods that can be used to calculate/estimate the CC and SD of herbivores on a wildlife ranch/reserve or in a breeding system has indicated that the extensive wild herbivore ungulate production method is suitable for all extensively managed animals on ranches/reserves. The intensive wild herbivore ungulate production method is ideal for estimating the CC and SD of animals on ranches that focus on breeding animals for live sale or trophy hunting. Using the incorrect method increases the chances of making costly mistakes. The refined ME, LSU, WHU, GU, and BU animal unit equivalents derived in this study will enable wildlife reserves, ranches, and breeding systems to accurately calculate/estimate CC and SD values. The appropriate long-term application of these methods will contribute to optimising animal and veld production and improving ecosystems and animal health.

Acknowledgements

C.A.S. would like to thank all of the fellow authors and their family members for dedicating their time to writing this paper. The authors would also like to thank G. Jordaan for helping with editing.

Authors' contributions

C.A.S. wrote the paper with input from N.V.R., M.W.V.R., J. du P.B., and R.B.

Conflict of interest declaration

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript.

References

Bothma, J. du P., Van Rooyen, N., & Van Rooyen, M.W., 2004. Using diet and plant resources to set wildlife stocking densities in African savannas. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 32(3):840-851. [ Links ]

Bothma, J. du P. & Du Toit, J.G. (eds), 2016. Game Ranch Management, 6th edition. Van Schaik, Pretoria, RSA. [ Links ]

Cheeke, P.R. & Dierenfeld, E.S., 2010. Comparative Animal Nutrition and Metabolism. CABI, Wallingford, UK. [ Links ]

Clauss, M., Lechner-Doll, M., & Streich, W.J., 2003. Ruminant diversification as an adaptation to the physicomechanical characteristics of forage. A re-evaluation of an old debate and a new hypothesis. Oikos, 102:253-262. DOI: 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12406.x [ Links ]

Costa, D.P. & Maresh, J.L., 2018. Energetics. In: Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, 3rd edition. Eds: Wursig, B., Thewissen, J.G.M., & Kovacs, K.M., Academic Press, Washington DC. pp. 329-335. Available from: https://www.elsevier.com/books/encyclopedia-of-marine-mammals/wursig/978-0-12-804327-1 [ Links ]

Danckwerts, J.E. & Teague, W.R., 1989. Animal performance. In: Veld management in the Eastern Cape. Eds: Danckwerts, J.E. & Teague, W.R., Department of Agriculture and Water Supply, Government Printer, Pretoria, RSA. pp. 47-60. [ Links ]

Del Monte-Luna, P., Brook, B.W., Zetina-Rejón, M.J., & Cruz-Escalona, V.H., 2004. The carrying capacity of ecosystems. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 13:485-495. DOI: 10.1111/j.1466-822X.2004.00131.x [ Links ]

Dekker, B., 1997. Calculating stocking rates for game ranches: Substitution ratios for use in the Mopani Veld. African Journal of Range and Forage Science, 14:62-67. DOI: 10.1080/10220119.1997.9647922 [ Links ]

Dhondt, A.A., 1988. Carrying capacity: a confusing concept. Ecologica Generalis, 9:337-346. [ Links ]

Gagnon, M. & Chew, A.E., 2000. Dietary preferences in extant African Bovidae. Journal of Mammalogy, 81(2):490-511. DOI: 10.1644/1545-1542(2000)081<0490:DPIEAB>2.0.CO;2 [ Links ]

Grossman, D., Holden, P.L., & Collinson, R.F.H., 1999. Veld management on a game ranch. In: Veld Management in South Africa. Ed: Tainton, N.M., University of Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg, RSA. pp. 261-279. [ Links ]

Grubb, P., 2005. Order Perissodactyla and Artiodactyla. In: Mammal Species of the World, 3rd edition. Eds: Wilson, D.E. & Reeder, D.M., John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, USA. pp. 629-722. [ Links ]

Hayssen, V. & Lacy, R.C., 1985. Basal metabolic rates in mammals: Taxonomic differences in the allometry of BMR and body mass. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology, 81:741-754. DOI: 10.1016/0300-9629(85)90904-1 [ Links ]

Heusner, A.A., 1982. Energy metabolism and body size. I. Is the 0.75 mass exponent of Kleiber's equation a statistical artifact? Respiration Physiology, 48:1-12. DOI: 10.1016/0034-5687(82)90046-9 [ Links ]

Hofmann, R.R., 1973. The ruminant stomach: stomach structure and feeding habits of East African game ruminants. In: East African Monographs in Biology, volume 2. East African Literature Bureau, Nairobi, Kenya. [ Links ]

Karasov, W.H., 1992. Daily energy expenditure and the cost of activity in mammals. American Zoologist, 32:238-248. DOI: 10.1093/icb/32.2.238 [ Links ]

Meissner, H.H., 1982. Theory and application of a method to calculate forage intake of wild southern African ungulates for purposes of estimating carrying capacity. South African Journal of Wildlife Research, 12(2):41-47. [ Links ]

Mentis, M.T., 1977. Stocking rates and carrying capacities for ungulates on African rangelands. South African Journal of Wildlife Research, 7(2):89-98. DOI: 10.10520/AJA03794369_3293 [ Links ]

Mentis, M.T. & Duke, R.R., 1976. Carrying capacities of natural veld in Natal for large herbivores. South African Journal of Wildlife Research, 6(2):65-74. [ Links ]

National Research Council (NRC), 2007. Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants, 8th edition. National Academies Press, Washington DC, USA. [ Links ]

Oberem, P. & Oberem, P.T., 2016. The New Game Rancher, 1st edition. Briza Publications, Pretoria, RSA. [ Links ]

Orban, B., 2014. Wildlife dynamics. In: Training Database for Wildlife Management, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, RSA. [ Links ]

Owen-Smith, N., 1999. The animal factor in veld management. In: Veld Management in South Africa. Ed: Tainton, N.M., University of Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg, RSA. pp. 117-138. [ Links ]

Peel, M.J.S., Biggs, H., & Zacharias, P.J.K., 1999. Perspective article: The evolving use of stocking rate indices currently based on animal number and type in semi-arid heterogeneous landscapes and complex land-use systems. African Journal of Range and Forage Science, 15(3):117-127. DOI: 10.1080/10220119.1998.9647953 15, 117-127 [ Links ]

Peel, M.J.S., Pauw, J.C., & Snyman, D.D., 1994. The concept of grazer and browser animal units for African savanna areas. Bulletin of the Grassland Society of Southern Africa, 5:61. [ Links ]

Sayre, N.F., 2008. The genesis, history, and limits of carrying capacity. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 98:120-134. DOI: 10.1080/00045600701734356 [ Links ]

Shepstone, C.A., Meissner, H.H., Van Zyl, J.H.C., Lubout, P.C., & Hoffman, L.C., 2022. Metabolizable energy requirements, dry matter intake and feed selection of sable antelope (Hippotragus niger). South African Journal of Animal Science, 52(3):326-338. DOI: 10.4314/sajas.v52i3.8 [ Links ]

Shepstone, C.A., Van Hoven, W., Bothma, J. du P., & Van Rooyen, N., In press. Ecological capacity and stocking rate. In: Game Ranch Management, 7th edition. Eds: Bothma, J. du P. & Du Toit, J.G., Van Schaik, Pretoria, RSA. [ Links ]

Shepstone, C.A., In press. Herbivores in enclosures. In: Game Ranch Management, 7th edition. Eds: Bothma, J. du P. & Du Toit, J.G., Van Schaik, Pretoria, RSA. [ Links ]

Skinner, J.D. & Chimimba, C.T., 2005. The mammals of the southern African subregion, 3rd edition. Cambridge University Press, Cape Town, RSA. [ Links ]

Tainton, N.M., Aucamp, A.J., & Danckwerts, J.E., 1999. Principles of managing veld. In: Veld Management in South Africa. Ed: Tainton, N.M., University of Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg, RSA. pp. 169-193. [ Links ]

Trollope, W.S.W., Trollope, L.A., & Bosch, O.J.H., 1990. Veld and pasture management terminology in southern Africa. Journal of the Grassland Society of Southern Africa, 7:52-61. DOI: 10.1080/02566702.1990.9648205 [ Links ]

Van Rooyen, N. & Bothma, J. du P., 2016. Veld management. In: Game Ranch Management, 6th edition. Eds: Bothma, J. du P. & Du Toit, J.G., Van Schaik, Pretoria, RSA. pp. 808-872. [ Links ]

Submitted 11 November 2023

Accepted 30 March 2025

Published 23 July 2025

# Corresponding author: craig.shepstone@gmail.com