Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Psychology in Society

On-line version ISSN 2309-8708Print version ISSN 1015-6046

PINS vol.66 n.2 Stellenbosch 2024

https://doi.org/10.17159/pins2024vol66iss2a6720

ARTICLES

The experiences of race relations amongst student leaders at a historically white South African university

Hlengiwe SelowaI; Benny MotilengII

IDepartment of Psychology, University of Pretoria hlengiweselowa@gmail.com; 0000-0002-9525-8199

IIDepartment of Psychology, University of Pretoria. benny.motileng@up.ac.za; 0000-0003-1827-0271

ABSTRACT

Recent protest movements such as #Rhodesmustfall and #FeesMustFall have highlighted uneasy race relations at South African universities. Although such incidents are crucial, equally important are the everyday realities of race relations that continue to define student lives in these institutions. The purpose of this study was to provide an understanding of student leaders' experiences of race relations at a historically white South African university. Guided by a qualitative research approach, Critical Race Theory (CRT) was the framework we used to explore race relations amongst student leaders. Purposive sampling was employed to recruit six student leaders across racial groups. They participated in a forty-five-minute semi-structured interview. Interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) was used to analyse the data. The findings suggest that the history and identities of universities as racially segregated in an unequal society, impacts race relations. Racial discrimination and distrust hamper racial integration in the student body and external political factors also affect student leaders' experiences of race relations. Our findings do show that friendships present an important opportunity to foster positive race relations, even though friendships are largely class dependent. We recommend that universities invest in personnel diversity training and the creation of platforms for intercultural and interracial exchanges.

Keywords: race relations, higher education, student leaders, universities

Introduction

This study draws on the Critical Race Theory (CRT) framework to explore student leaders' experiences of race relations in a South African university (Maylor et al., 2021). Race relations within the university environment are well documented in South Africa (Cornell & Kessi, 2017; Kiguwa, 2014; Mangcu, 2017; Wertheim, 2014) and continues to form much of the dialogue when considering transformation within institutions of higher learning (Mekoa, 2018). To ascertain and maintain white supremacy, the South African Apartheid government formulated laws and regulations that systematically violated the human rights of Black people thus creating an environment for feelings of hostility across racial groups and distorting race relations (Ratele, 2021). The divisions across race during apartheid ensured minimal inter-racial contact where power and privilege rested with White racial groups (Hunter, 2020).

Institutions of higher learning are intended to serve as cosmopolitan hubs that reflect racial diversity (Cross, 2020) and provide an opportunity for interracial contact and integration in post-apartheid South Africa. The change in student demographics to include more Black students has confronted universities with racial tensions amongst staff as well as students. The translation of equity policies such as the promotion of equality and prevention of unfair discrimination Act 4 of 2000 (Kok, 2017), into everyday practice within universities remains poorly implemented and has a negative impact on race relations (Mekoa, 2018). The hashtag movements in South African universities such as the #RhodesMustFall (Chaudhuri, 2016), #Afrikaansmustfall (Ngoepe, 2016), #OpenStellenbosch (Mortlock, 2015) and the nationwide #FeesMustFall movements (Baloyi & Isaacs, 2015) have highlighted difficulties students face in institutions of higher learning. At the centre of all these movements was a need to transform and decolonise higher education in South Africa (Baloyi & Isaacs, 2015). Students highlighted the way in which apartheid patterns of racism and exclusion remained intact within institutions of higher learning thus perpetuating the alienation of Black students (Mortlock, 2015).

Although there have been positive strides such as having representative student bodies who are concerned with transformation in institutions of higher education (Mekoa, 2018), the outcry from various student movements highlighted that more needs to be done in terms of inclusivity and equality. Although occasional protest movements are crucial, equally important is the everyday reality of race relations that continue to define the lives of many South Africans. The disregard for past injustices (e.g. enforced segregation in all aspects of life, including education, healthcare, and employment) hinders South Africans' ability to address the impact of these injustices on their current and future inter-racial relationships. (Pirtle, 2022). To this extent, "Black people have and continue to be, systemically disadvantaged and discriminated against" (Carolissen & du-Toit, 2022, p. 15).

Available studies (Belluigi & Thondhlana 2022; Corno et al, 2022; Moopi & Makombe 2022; Vincent 2008) on race relations and transformation in South African institutions of higher education show that the institutional setting within historically White universities 1) alienates and excludes Black students (Bazana & Mogotsi, 2017), and 2) that material and social realities remain tied to the construct of race. It is important to consider race relations, generally viewed as focusing on interpersonal relations, within the context of CRT since it provides an opportunity to consider race relations themselves as socially constructed and not at an individualistic level. When this is not acknowledged, we ignore the way in which inequalities within universities are still part of the ongoing legacy of neo-colonialism and white supremacy (Carolissen & du-Toit, 2022). High levels of informal racial segregation still exists and the segregation manifests as a specific spatial configuration (Munoriyarwa, 2021, Dixon et al., 2020). A study by Corno et al (2022) in a large South African university, found that unfavourable perceptions of Black students held by White students can be lessened by sharing living space. These studies underscore the need for a deeper understanding of race relations in higher education to create inclusive and equitable environments for all racial groups (Johnston-Guerrero, 2018).

The views of student leaders were central in this study as they are the drivers and implementers of the mandate from university students. Student leaders refer to students who are part of a student organization that is regulated by the Department of Student Affairs in an elected position. The student leaders who participated in this study were registered at the study's university for more than a year and were currently university students. Historically, student leaders in South Africa played a crucial rule in mobilising students and the greater society (Chapman, 2016). The ideas of prominent student leaders such as Steve Biko are still alluded to decades after his death (Ahluwalia & Zegeye, 2001). Student leaders are important stakeholders in institutions of higher learning as evidenced by their ability to influence the manner in which education is managed and how social issues are integrated into campus debates. Current work on student leaders have focused on policy and social justice in relation to student leader experiences (Luescher et al, 2020) but little work has focused on student leaders and race relations. It is this gap that this study aims to explore.

Theoretical framework

The CRT framework provided a lens through which we explored student leaders' experiences of race relations at a historically white South African university. This study is founded on the CRT tenets that racism is socially constructed, it is ordinary and not aberrational, material determinism, and intersectionality. Delgado and Stefancic (2023) argue that race is not objective, but rather shaped by hegemonic societal interests. In keeping with this view, this study is informed by the belief that racism is ordinary (a regular, everyday experience woven into the fabric of society), rather than an unusual or extraordinary event. It is embedded in societal norms, policies, and practices. Thus, the racialised experiences of student leaders are seen as embedded in university norms and daily practices.

Material determinism states that racism advances the interests of White people over other racial groups (Bell, 2018). Hegemonic societal interests which assume White superiority manifest as macroaggressions and microaggressions. Macroagressions manifest as structural exclusions towards Black and marginalized people such as maintaining dominance through minimizing indigenous languages in universities. Microagressions manifest in behaviours that dismiss the hardships that Black people face, suggesting that they are overly sensitive or imagining racism (Belluigi & Thondhlana, 2022). Social construction holds that racial identity and race are concocted within society as people relate to each other and are devoid of objectivity (Delgado & Stefancic, 2023). Thus, race is not a biological reality but a social construct. The understanding of what constitutes being Black differs in different contexts, indicating that race is normatively constructed.

One of the fundamental tenets of CRT upon which we based our understanding of the findings is intersectionality. Delgado and Stefancic (2023), drawing on Crenshaw (2013) maintain that intersectionality refers to the notion that individuals hold multiple social identities (e.g. race, gender, sexuality, class) that intersect and influence their experiences. In the South African context, CRT has been used by Moorosi (2021) to analyze educational leadership policies, institutional culture, and the experiences of black academics in historically White universities. CRT has also been valuable in its ability to frame issues of privilege, inequality, and racial disparities in educational settings (Graham & Moye, 2023). Finally, CRT enabled us to understand how student leaders experience race relations in a university context (Ajani & Gamede, 2021) which was particularly valuable in this study.

Methodology

A qualitative research approach was followed given the aim to explore student leaders' experiences of race relations. Qualitative research ensures that meaning can be surfaced through deep reflective dialogue between the researcher and participants. The participant is viewed as a co-constructor of the reality or realities that emerge from the researcher-participant interaction (Willig, 2013).

Phenomenology was employed in this research study as the methodological strategy. Qutoshi (2018) posits that as a method of inquiry it is not limited to an approach to knowing. Phenomenology is concerned with phenomena that result in an individual's consciousness as the person engages with the world, and it maintains that descriptions of one's experiences are subjective regarding one's understanding of the world (Willig, 2013). The study employed interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) to analyze the lived experience of race relations amongst student leaders, recognizing the interconnectedness of social contexts within an individual's being (Luth-Hanssen & Fougner, 2020). IPA was deemed suitable for this study because it seeks to ask questions of individuals within a specific context (Toffour, 2017) which is aligned to this study's aim of exploring the participants' experiences.

Study participants and procedure

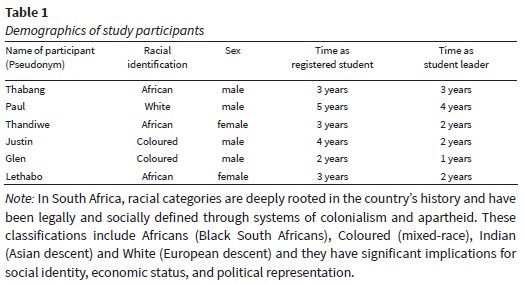

We employed purposive sampling to recruit six racially diverse student leaders. The small sample size is consistent with interpretive phenomenology where routinely smaller sample sizes of 10 or less is common because it enables comprehensive and detailed analysis, to achieve an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon (Groenewald, 2004). The inclusion criteria for the sample were that participants should be elected student leaders for a minimum of one year. Participants were part of the Student Representative Council (SRC) representing different student political parties and societies. Although there was racial diversity amongst the participants, they did not represent all racial groups on campus. A brief demographic description of each participant follows in Table 1 below.

One participant who initially agreed to participate withdrew from the study. The study involved four male and two female participants who served as student leaders for one to four years after registering for one to five years. Participants were interviewed at a place and a time convenient to them.

We utilized 45 minutes semi-structured interviews to gather data on the experiences of student leaders in a South African university regarding race relations. After receiving consent from the participants, the interviews were audio-taped and kept at the university for five years.

Methodological limitations and reflexivity

In this enquiry the participants who volunteered were drawn from African, White and Coloured racial groups. Attempts to secure an interview with an Indian student leader failed. This study was conducted by Black African researchers and might have yielded different findings if it was undertaken by researchers from different racial groups. Some of the researchers' own ideas about race relations were challenged during the interviews. We did not expect that a White student leader could be as sincere as Paul was which emphasizes some of the work that all of us have to do to overcome deeply held prejudice. Some interviews left us feeling sad. Thandiwe's interview, especially, evoked sad memories and feelings that we experienced in our own previous race relations encounters while at university and elsewhere.

Data Analysis

The interview transcripts were analyzed using interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA), as per Pietkiewicz & Smith (2014) guidelines. The process entailed four core steps; firstly, reading the data multiple times and making notes, followed by transforming the notes into emergent themes. Thirdly, we looked for patterns and relationships between identified themes and grouping related themes together. Lastly, we documented the study findings.

Ethics

We obtained ethics clearance from the research ethics committee of a university in the Gauteng province of South Africa. Permissions to interview student leaders were obtained from the registrar and the director of student affairs of the university. Participants gave consent to be interviewed by signing the informed consent form. Pseudonyms were used and researchers themselves transcribed the interviews to protect participant anonymity.

Findings and Discussion

Willig (2013) suggests that phenomenological analysis requires researchers to immerse themselves in the study data. Following this approach, we immersed ourselves in the interview material which allowed us to establish relationships between various themes. The themes were 1) Historical identity of the university, 2) Racial Integration, 3) Culture, 4) Intersectionality and 5) Friendship, were identified and are discussed below.

Historical identity of the university

This study was conducted at a historically white university and the adherence to its historical identity left Black students feeling alienated within the university space. Thabang explains:

If every day, uhmm, for example, I am going to a campus and it is a very Afrikaans campus and you feel excluded, it is not a space you would want to be in. It is not a space, I would submit, you would want to thrive in due to the lack of uhmm, for instance, you would feel excluded from the university space. (Thabang)

Participants described ways in which the historical identity of the university lingers. This includes the residence culture, language, as well as the different treatments that students receive within the university depending on their race. Justin elaborates:

Like, for example, if a Black student would approach a White lecturer, they will sort of be short with the student and say, "I said do 1, 2, 3" and that is it. But then when a White student approaches a White lecturer and they start speaking in Afrikaans, you can see that there is more favouritism and there is bias between the lecturer and students. So, often White people would come out with the lecturer speaking Afrikaans and it's like they are friends and stuff like that, but when a Black student is in the same situation, it's completely different. (Justin)

Thabang and Justin's statements underscore the impact of exclusion on students' ability to thrive within the university. Although the university reflects a cosmopolitan hub, language and lecturer attitudes still contribute to Black students feeling excluded. CRT's tenet of racism being ordinary and material determinism speaks to how systemic racism and exclusionary actions (speaking Afrikaans only when many Black students cannot understand Afrikaans) highlights how such subtleties hinder the academic and personal development of marginalized students (Nakajima et al., 2022). This finding supports an observation by Mekoa (2018) that the everyday practices within a historically White university does not reflect the multicultural and multiracial community of students it serves.

Justin suggests that because of the historical identity of the university, racial conflict is inevitable on the university campus:

I think at this university, it is inevitable and wherever you are, I think within this institution you are gonna face certain racial conflict with people. Whether it be from White people or from Black people, but I think at this institution, given the fact that it is, it was an Afrikaans White institution, I think that it is inevitable that you will be confronted with race situations. (Justin)

However, the challenge of racial conflict as described in this study is not limited to the university but extends to South African society, in general. Thandiwe cites an example of how during student protests, police responses to students differed according to the race group that was protesting. Systems like the police, as elaborated by CRT, are used to protect White interest. CRT furthermore states that change within such systems is unlikely to happen unless it benefits the dominant group in power.

And if you look at demographics specifically, you'll begin to understand that there is, should I say a form of care that is applied or rather a form of diplomacy that the state, even the state will apply when White children are there. But the minute it is Black bodies, they have no fear whatsoever of being trigger happy. (Thandiwe)

Race relations were also influenced by student political parties where race is used in a divisive manner in order to gain votes and power or dominance. Although no political party is overtly racially exclusive, political parties especially in South Africa are largely understood along racial lines. Glen summarised it as follows:

The notion of, if I can go back, the notion of apartheid, if I can put it like that. We are still hung up on that even today if you look at student political parties on campus. You look at the (names political party) political party, last year with the entire student elections, how they went on. So, everybody, they made it a race thing, when a White representative came up, they started booing her. When a Black representative came up they were cheering. So, that is all I can say about that, that is all I can say. (Glen)

He suggests that White students are actively discouraged by crowds from becoming student leaders. In line with CRT, Whiteness as a property imply that they are already seen as occupying position of power and privileged.

The history of South Africa is such that racial policies were enforced such that physical racial integration was prohibited. Public facilities were race coded where the beach, a bench or a toilet would be demarcated for "Europeans only" (Clark & Worger, 2016), thus disabling positive race relations and alienating race groups from each other. Thandiwe and Paul describe this legacy of apartheid at their university:

You then have your Indians at this university if you go to (mentions public space at the university) you will notice that there is a whole culture at this university, where there is your Indians, there is your Blacks, there is your Whites and it's just some of your Coloured people that try to alternate within the system and it's because of what they particularly associate with because of their growth. (Thandiwe)

I am quite a diverse individual and most of my friends are also Black students and everything. So, I have that ease there, but then it's always that when I am walking with that bigger group or when I am at a party and everything and my White friends see me, and I am like "Don't you guys wanna come to this party with me" it is "No we don't wanna go to Yamies, they don't play nice music." But, I know that it's not that they don't play nice music, it's that there are too many Black students there. (Paul)

Thandiwe and Paul's comments reflect both on the power dynamics of racial segregation and White privilege or supremacy. In line with the CRT principles, Whiteness is a property used to enforce and bestow privileges. Paul's comments emphasize the relations the race superior complex which even if not inherent, fixed nor objective but is created and endowed with pseudo-permanent characteristics. Black music represents Blackness and is frowned up and White music is elevated as "nice music" and symbolically becomes a cipher good and nice. Enforcing the stereotype that Black is bad, dangerous and should be avoided.

Although the university campus does not have markings that designate particular spaces to a given race or culture, the participants' related experiences where that they felt the university mainly accommodated and protected White Afrikaans culture. The inequality that still persists in institutions of higher learning fosters uneasy race relations as expressed by a number of participants. Thandiwe and Thabang's quotes are emblematic of student experiences:

Commonly, you are black, you are poor, these spaces were not built for you to begin with and the fact that you are here already agitates White people. (Thandiwe)

If every day, uhmm, for example, I am going to a campus and it is a very Afrikaans campus and you feel excluded, it is not a space you would want to be in. It is not a space, I would submit, you would want to thrive in due to the lack of uhmm, for instance, you would feel excluded from the university space. So, these are the things that as a university, as a leadership, you want to see a neutral space, where all students can feel included, and it will help them strive for their best potential. (Thabang)

Student leaders noted that there was a racial divide within the university where certain spaces are informally coined White, Black, Indian or Coloured. The observation by Thabang echoes Bazana and Mogotsi (2017)'s findings that historically White universities in South Africa continue to alienate and exclude Black students, even in the postapartheid era. Their findings highlight the persistent race relation dynamics that affect the experiences of Black students in these institutions (Munoriyarwa, 2021).

The inclination towards keeping to one's own race is embedded in the historical practices that sought to separate people according to race. These are the results of the structural policies of apartheid which successfully ensured that people internalized a sense of superiority or inferiority and felt safe within their own spaces. This inclination was noted by Hooks (2013) as a defense mechanism by various racial groups. Hooks asserted that Black people stayed together in groups to defend themselves against the victimization they often suffer as a result of oppressions. Student leaders' experiences as reflected in quotes provide classic examples of the CRT framework tenet of material determinism demonstrating self-segregation in universities, where Whiteness, is used to maintain privileges, allowing White students in democratic South Africa to maintain a sense of superiority. Dixon et al. (2020) working in South African universities, concluded that intergroup contact can reduce prejudice, even though opportunities to experience such contact are often constrained by systems of segregation. Vincent (2008) concurs that, while the dismantling of apartheid has led to many situations in which South Africans come into closer contact with one another, this increased 'contact' occurs within a context of unequal power relations where Whiteness continues to be privileged over Blackness and does not amount to greater racial integration.

Student leaders must grapple with their own racial identity whilst working towards serving a diverse student population. Their accounts of how history affects race relations highlights the difficulties the university is faced with in terms of being more inclusive in theory and practice. As noted in this study, the pain of apartheid is still felt in postapartheid South Africa. Carolissen and du Toit (2022) lamented this situation within universities when they posited that to ignore existing racial discriminatory tendencies is to ignore the way in which inequalities are still part of the ongoing legacy of neocolonialism and white supremacy. The tendency to ignore past inequalities such as unequal access and affordability, many students from disadvantaged backgrounds struggling to afford the cost of university life, including tuition fees, accommodation, textbooks, and living expenses, is still rife. Furthermore, actions such as encouraging colour-blindness by implementing race-neutral admission policies which treat all applicants the same regardless of their racial background and historical disadvantages, are shortsighted since they focus on equality instead of equity that recognized difference entrenched by structural advantages and disadvantages. Finally, to foster equality without justice is limiting for positive race relations. Many universities have increased the number of Black students in historically white institutions while the environments and curricula often remain Eurocentric and unwelcoming to the cultural and historical perspectives of Black students. These are examples of regular, everyday practices of racism being ordinary, rather than an unusual or extraordinary. In line with the social constructionism tenet, students categorize and organize themselves within given spaces in the university, mainly according to societal order which was and is still race-based in South Africa. Lethabo noted that this propensity led to misunderstandings experienced across racial lines were because the majority of White students were not concerned with past inequality nor reparations:

These social issues that affect us don't affect them, they don't need to be concerned, they have the privilege to be comfortable in their spaces and know ukhuthi aaah even if taxis strike tomorrow I am fine, I have got my car, or I live very close I can walk, I can take a bicycle, I can you know, things like that. And it's not the same, Black people constantly will have to fight, we will have to talk about these issues because we are the ones that are affected, essentially. (Lethabo)

This proclivity creates division along racial lines and race relations tend to mimic those experienced during apartheid. Thus, there is little to no change as reparations do not serve the interest or benefit the dominant group. As long as there is no interest convergence as suggested by CRT tenets, there will be no change in the racial relations in the university, irrespective of the policies, the idealism and altruism that may exist. Paul underscores this statement when he laments that their commitment to reparations caused them to be labeled a sell-out by the White community:

I have been coined the term sell-out in the White community. They call me things like chameleon, that I can just blend into other groups just to make sure that they like me. (Paul)

The understanding of difficulties that students face such as financial problems also affects how student leaders perceive, and in turn act, in addressing the issue. Justin explained that they empathized more with Black students whilst another declared that their work only focuses on helping Black students due to historical imbalances:

Even when we are sitting in appeals, we go there with one mandate and that is to try and fight for Black people to get readmitted; not to go there and try and make friends with these people. (Justin)

Racial integration

Racial discrimination, which manifested in racial stereotypes, racial primes and macroaggressions, was pointed out as a challenge to racial integration within the university space which translates into strained race relations. Racial discrimination or the perception thereof hinders good race relations. Black students are said to be treated with impatience and disregard. They mentioned that White lecturers tended to be friendlier to White students and engaged with them more than their Black counterparts. While Black students are usually rushed out, their White counterparts would walk out with the lecturer in conversation about a given subject. In accordance with CRT lenses these are examples of the hidden realities of racial oppression which impacts students and perpetuate racialized norms within the university (Kubota et al., 2021).

The way in which the university management responded to students across race was mentioned as a contributing factor to negative race relations. White student leaders were largely perceived as more competent than their Black counterparts by the university's management. It was also relayed that when White student leaders made contributions in meetings, they were acknowledged for their brilliance whereas when Black student leaders made the same contributions they were ignored. This disparity in response is experienced negatively and fostered insecurities in the abilities of Black students. Critical research theorist Harris (1993), in her seminal work titled "Whiteness as property" argued that Whiteness is treated as a form of property, conferring and protecting privileges and advantages on those who are considered white. Critical studies have highlighted white privilege, which refers to the unearned advantages and societal benefits received solely based on their race group. (Blevins & Todd, 2021). Paul, Lethabo and Thabang said:

But largely I personally feel that the management feels that White SRC members are far more competent and knowledgeable and hardworking than the Black SRC members. (Paul)

When you are a White student there is some level of respect that you are given; when you are a Black student you are treated with impatience, you are disregarded. It is as though you are less of a human being. (Lethabo)

That difference, preferential treatment, one man uses the word, nigger gets away with a warning and apologising on Facebook. The other, a Black student leader has to go through uhmm, community service and all these other things, but one would dare argue that both these things are the same. Why is there different treatment for the Black student leader as opposed to the White one who uses hate speech per se? (Thabang)

Paul, a White student leader offers an alternative understanding of how everyday interactions and institutional practices perpetuate racial inequalities. It captures the existence and use of microaggressions or prejudices towards individuals or groups based on their race in the university setting.

I believe in call out culture and you would often find that some of the Black SRC members would think I am calling them out because they are Black, when I am calling you out because they are inefficient. That kind of situation where the race card does get pulled more often than it should as a defence against you possibly not doing your job. So, why is the White guy calling me out when I am not doing my job, is it because I am a White guy, or you are just not doing your job? (Paul)

Roberts et al., (2016) noted that although race relations in South Africa were improving, they were characterized by lack of trust across racial lines. The study findings show that the lack of trust along racial lines has led to the development of the ingroup outgroup phenomenon. It is the tendency of race groups to stick together and characterize those of a different race as opponents. Erasmus and de Wet (2011) found that students in South African higher education institutions regarded each other as separate (us and them) and when a student leader agrees with a student of a different racial group, they are often labeled as sell-out or a betrayer of their own race. Paul, who supported protest action that was driven largely by Black students within the university explained that fellow White students were asking why they were helping "them":

And then the white friends are often just like 'No, he is not like one of us really anymore, he is not liking our elitist kind of way. 'And I found out very quickly what they were like "(participants name)", they got very angry with me, they were like "(participants name) why are you assisting with them shutting down our campus? You are making me postpone my exam and you're helping them. (Paul)

Similarly, Thabang noted how protest action at the university exacerbated racial divisions:

So, it was interesting to see that racial divide and it is something that has stayed uhmm in every protest I have seen in this university including when I observed the fees must fall in 2016. It leads to a situation where on one side you had the White people and then you had a line of security and then the Black people were on the other side. (Thabang)

This is consistent with the views of (Ngoepe, 2016) where there was an evident racial divide and tension during protest action at a South African university. This phenomenon indicates that the realities of students within the university campus are not similar across race such that issues that one race group fights to do away with, the other group fights to protect. The lack of similarity helps to foster the ingroup outgroup phenomena which characterizes negative race relations.

Culture

The results indicate that the study's university culture creates an uneven ground to relate across race where White Afrikaans students adapt easily, and their colleagues struggle to grasp the university environment. CRT contends that racism is not just an individual attitude or bias but is deeply embedded in social structures and institutions. It examines how legal and societal structures perpetuate and reinforce racial disparities. Pattman and Carolissen (2018) maintain that experiences of marginalisation were now linked to institutional cultures associated with continued use of perceived colonial symbols, names, language and academic texts. Symbols within the university mainly resonated with students who are White and Afrikaans speaking. Most participants noted that if they were not White and Afrikaans speaking, they did not feel accommodated. The initiation processes within residences primarily alienated students who were not White and Afrikaans speaking. Lethabo and Thabang reported feelings of discomfort at the practices that students had to engage in during their initiation into the university.

Well, I mean like, for instance, there were various expectations of us in res as first years that the White, let me say the Afrikaans students who were mostly White were comfortable with doing. And we just didn't understand, "Why are we doing this, what does it mean?". And then they were like greetings that were tailored for the male residences right and for instance, in, in, like from a Black perspective or from a Black culture rather it's not really things you are comfortable saying. (Lethabo)

It was just the statues, the pictures, the signs on the wall and the writings, they were not things that a Black student would find accommodating. I recall it, it was a very very White space. (Thabang)

Bryd (2017) suggested that individuals from disadvantaged groups remove themselves completely from their group identity to be accepted within historically White universities. To overcome this, institutional culture has to be interrogated in terms of how it excludes and includes given race groups. Thus, the everyday practices within the university space should be reflective of a diverse student body.

Every participant spoke of the way in which language has either affected or continues to affect race relations as they experienced them within the university. The use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction was seen to be the cause of the racial divide among students by some student leaders. As a result, the protest action that called for the fall of Afrikaans heightened the tension across racial lines. Lethabo noted that the call for the fall of Afrikaans was a call to equality and others understood it as an attack on the Afrikaans language and their culture:

Afrikaans must fall is a movement for inclusiveness, it's a movement for a free space for diversity, it's a movement for equality, it a movement for ja, equalizing the playing fields. That whole of English is not my mother tongue, English is not your mother tongue, now we are equal, let's get this degree in the same language. (Lethabo)

The need to assimilate into the university, to speak and sound Afrikaans to be acknowledged, was highlighted. The results support Bazana and Mogotsi (2017) findings that students' sense of social identity, which includes language and traditions, and consequently self-esteem and self-concept, are altered in these institutions. Thandiwe addresses this issue eloquently:

So, you will never acknowledge me; in essence, you are saying that I won't be human enough until I speak a certain way, until I walk a certain way, until I behave a certain way. So, I must disregard who I am, my culture, my experiences so that you are comfortable enough to tolerate me? Is that what you are saying in essence? (Thandiwe)

Other student leaders did not view the Afrikaans must fall movement as a call for equality but rather as an attack on the Afrikaans language:

Like with #Afrikaansmustfall, it's never gonna happen, like you can't just take away an entire language that basically built part of the nation. Like Afrikaans is there, Afrikaans will always be there, you can't take it away. If you want to take Afrikaans away in schools, Afrikaans will be somewhere else as well. So, you can't do that, if I can put it like that. (Glen)

Not all students whose home language is Afrikaans are White. Glen who is Coloured, was opposed to the fall of Afrikaans whilst another Coloured participant supported Afrikaans being eliminated as a language of instruction. Therefore, language divides and unites across racial lines and can be used to either improve race relations or to impede them. This finding emphasizes the sensitivity and complexity of addressing language issues. It implies that the language issue may not be a straightforward issue that affects students within the same racial groups in a homogenous way. Walker (2005) also found that the ability of Black students to speak Afrikaans within an institution that is historically White Afrikaans resulted in these students navigating relations easier than their peers who could not speak Afrikaans. The implication is that language therefore presents an opportunity to foster good race relations.

Intersectionality

According to Crenshaw (2013) and Lewis et al., (2017), individuals hold multiple social identities (such as race, gender, sexuality, class) that intersect and influence their experiences. Race and class are at times synonymous, where white students are predominantly middle class and Black students are predominantly poor. This scenario resonates within the South African context given the history of inequality (Finschilescu & Tredoux, 2010). Our findings show that students gravitated towards each other because of their class. Complicated relations were noted between rich students and poor students. Paul suggests that Black and white students cohere around class and that these groups are racialised where poor students are predominantly Black and middle-class students are predominantly White:

The race relations, you see some groups being extremely hostile, and then you see other groups being very homogenous, being very grouped together and like recognising their diversity. But normally it's because you will see that a lot of the Black students (are poor).....we do get also students who are coming from model C schools, White schools, predominantly White schools and they have been socialised with the White students and they are coming here as friends. (Paul)

However, Lethabo suggests that class allegiances occur not only across racial groups but within Black groups as well. She often feels ridiculed by Black students since, as student leaders, they are accused of being partial to middle class students with little attention to advance issues that affect poor Black students. Student leaders therefore continuously must prove their commitment and understanding of the issues affecting working class students:

But ja, the political student leaders, they just, they don't think we have Black students' interest at heart. They think we have, or we enjoy certain privileges or maybe because we are from a certain (middle) class or something. They just assume because you are (mentions student organisation) you enjoy the same, not the same, but nearly the same benefits White people generally enjoy. (Lethabo)

Lethabo's conflict is echoed by Erasmus and de Wet (2011) where participants also suggested that class position blinds middle class students to the disadvantages experienced by poorer students.

Thandiwe suggests another area of intersection, gender and race. She foregrounds how her gender struggles are compounded by racialised experiences:

Do you understand that being a Black woman is like being Black times two? So, you are just nje, you are the worst kind of violation that could possibly exist. So, you then look at how we treat one another, look at our gender relations; you'd find that White men over any women of colour as we are so classified, they will always act in a very supremacist manner. Do they actually have, do they have the same respect that they'd give to another White colleague, that they'd give to a Coloured woman, an Indian woman, a Black woman? So, when we start discussing those relations, gender roles come into play. (Thandiwe)

These excerpts by Paul, Lethabo and Thandiwe demonstrate that race relations are complex because the experience thereof is dependent on intersections of social identities. Despite the pessimistic view presented in this section, the study revealed that interracial friendships provide an opportunity to create good racial relations.

Friendship

Participants spoke about their experiences of interracial friendships and the manner in which that has positively affected their experiences of race relations. Lethabo emphasises that having friendships across race has resulted in an understanding of the realities and cultures across racial groups:

And as SRC or rather as individuals, we visit each other's spaces as friends so, (mentions colleague) is White he can come into our space, Black people and we will speak English and we will talk and you know it's, there are things that he will do that you know we will make a joke about like "Hahaha White things." Things that he will say like, "lyooh Black people," but it is just cultural differences. Like cultural shock I suppose whatever, but it's fine, it's not really problematic. (Lethabo)

Having cross racial friendships broadens students' appreciation of difference which resonates with Corno et al (2022)'s study that found that inter racial relations and friendship lessens negative perceptions. Lethabo also empathized with a White friend who was rejected by some White students because of her interracial friendships:

I had a White friend neh, I am still friends with her. And she was, she is very, she grew up in a foster home with lots of Black people. So, she understood certain things that we were not comfortable with and she understood why we were not comfortable with it. And now it became a thing of ok now she is for the Black people and not the White people and people like they treated her sort of like as a traitor or something like that. (Lethabo)

Similarly, Paul highlighted the complexities of interracial friendships where he had to distance himself from some White people who continued to engage in racist behaviour in his presence:

One of my best friends is Black and I know that that could possibly offend them and by right it should offend me that you have just said it. So then, I have never been able to keep up with how the Afrikaans culture, how its beliefs and the beliefs in the English culture and the beliefs of the elitist student who is sitting there. I know I come from a family of wealth, but I have never been able to sit around the table where everybody is enjoying a fancy dinner and they all like, "Oh no, did you see that truck protest, now how must I get to my beach house in Umhlanga. (Paul)

Interracial friendships foster racial integration and provide opportunities to learn about difference although there are complex challenges associated with them such as rejection by one's own racial group.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to explore student leaders' experiences of race relations. Using the CRT framework, the results revealed that racialised experiences are embedded in South African society and impact daily on student experiences, according to student leaders. The results highlighted the ways in which the historical identity of the university, personnel discrimination along racial lines, racial mistrust, class perceptions and racial mistrust impede good race relations. The results also suggest that interracial friendships and using a common language can foster good race relations amongst the student body. It is therefore clear that while race relations may be framed as interpersonal interactions, they are fundamentally shaped by the structural South African and university contexts in which they play out.

This study primarily recommends that the everyday experiences of students, such as these reflected in this study, should frame university policies and filter through to all levels of management to inform personnel and student diversity training and the creation of platforms for intercultural and interracial exchanges.

References

Ahluwalia, P., & Zegeye, A. (2001). Frantz Fanon and Steve Biko: Towards Liberation. Social Identities, 7(3), 455-469. [ Links ]

Ajani, O. A., & Gamede, B. T. (2021). Decolonising Teacher Education Curriculum in South African Higher Education. International Journal of Higher Education, 10(5), 121-131. [ Links ]

Baloyi, B., & Isaacs, G. (2015, October). South Africa's 'fees must fall' protests are about more than tuition cost. CNN. Retrieved from http://www.edition.cnn.com [ Links ]

Bazana, S., & Mogotsi, O. P. (2017). Social Identities and Racial Integration in Historically White Universities: A Literature Review of the Experiences of Black Students. Transformation in Higher Education, 2, 25. [ Links ]

Bell, D. (2018). Faces at the bottom of the well: The permanence of racism. Hachette UK. [ Links ]

Belluigi, D. Z., & Thondhlana, G. (2022). 'Your skin has to be elastic': The politics of belonging as a selected black academic at a 'transforming'South African university. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 35(2), 141-162. [ Links ]

Blevins, E. J. and Todd, N. R. (2021). Remembering where we're from: community- and individual-level predictors of college students' white privilege awareness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 70(1-2), 60-74. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12572 [ Links ]

Bryd, W.C. (2017). Poison in the ivy: race relations and the reproduction of inequality on elite college campuses. Rutgers University Press. [ Links ]

Carolissen, R., & du-Toit, N. B. (2022). Transformation of Community-based Research in Higher Education. International Journal of Critical Diversity Studies, 5(1), 9-21. [ Links ]

Chapman, R. D. (2016). Student resistance to apartheid at the University of Fort Hare: Freedom now, a degree tomorrow. Rowman & Littlefield. [ Links ]

Chaudhuri, A. (2016). The real meaning of Rhodes must fall. The Guardian, 16, 16. [ Links ]

Clark, N. L., & Worger, W. H. (2016). South Africa: The rise and fall of apartheid. Routledge. [ Links ]

Cornell, J., & Kessi, S. (2017). Black students' experiences of transformation at a previously "white only" South African university: A photovoice study. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(11), 1882-1899. [ Links ]

Corno, L., La Ferrara, E., & Burns, J. (2022). Interaction, stereotypes, and performance: Evidence from South Africa. American Economic Review, 112(12), 3848-3875. [ Links ]

Crenshaw, K. (2013). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of anti-discrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. In K. Maschke (Ed.), Gender and American Law: Feminist legal theories. (pp. 23-51). Routledge. [ Links ]

Cross, M. (2020). Decolonising universities in South Africa: Backtracking and revisiting the debate. In I. Rensburg, S. Motala and M. Cross (Eds.), Transforming Universities in South Africa (pp. 101-130). Brill Publishers. [ Links ]

Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2023). Critical race theory: An introduction (Vol. 87). New York University press. [ Links ]

Dixon, J., Tredoux, C., Davies, G., Huck, J., Hocking, B., Sturgeon, B., ... & Bryan, D. (2020). Parallel lives: Intergroup contact, threat, and the segregation of everyday activity spaces. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(3), 457. [ Links ]

Erasmus, Z., & De Wet, J. (2011). Not naming race: some medical students' perceptions and experiences of 'race' and racism at the Health Sciences faculty of the University of Cape Town. Widening circles, case studies in transformation, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Finchilescu, G., & Tredoux, C. (2010). The changing landscape of intergroup relations in South Africa. Journal of Social Issues, 66(2), 223-236. [ Links ]

Graham, K. L., & Moye, J. (2023). Training in Aging as a Diversity Factor: Education, Knowledge, and Attitudes Amongst Psychology Doctoral Students. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 22(1), 39-54. [ Links ]

Groenewald, T. (2004). A phenomenological research design illustrated. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3(1), 42-55. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690400300104 [ Links ]

Harris, C. I. (1993). Whiteness as property. Harvard law review, 1707-1791. [ Links ]

Hooks. B. (2013). Writing beyond race: living theory and practice. Routledge [ Links ]

Hunter, M. (2020). Race and the geographies of education: markets, white tone, and racial neoliberalism. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 110(4), 1224-1243. [ Links ]

Johnston-Guerrero, M. P., & Tran, V. T. (2018). Is it really the best of both worlds? Exploring notions of privilege associated with multiraciality. Understanding and Dismantling Privilege, 8(1), 16-37. [ Links ]

Kiguwa, P. (2014). Telling stories of race: A study of racialised subjectivity in the post-apartheid academy (Doctoral dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, Faculty of Humanities). [ Links ]

Kok, A. (2017). The promotion of equality and prevention of unfair discrimination Act 4 of 2000: How to balance religious freedom and other human rights in the higher education sphere. South African Journal of Higher Education, 31(6), 25-44. [ Links ]

Kubota, R., Corella, M., Lim, K., & Sah, P. K. (2021). "Your English is so good": Linguistic experiences of racialized students and instructors of a Canadian university. Ethnicities, 23(5), 758-778. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687968211055808 [ Links ]

Lewis, J. A., Williams, M. G., Peppers, E. J., & Gadson, C. A. (2017). Applying intersectionality to explore the relations between gendered racism and health among Black women. Journal of counseling psychology, 64(5), 475. [ Links ]

Luescher, T. M., Webbstock, D., & Bhengu, N. (2020). Reflections of South Africa student leaders 1994-2017 (336). African Minds. [ Links ]

Luth-Hanssen, N. and Fougner, M. (2020). Well-being through group exercise: immigrant women's experiences of a low-threshold training program. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 16(3), 293-305. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijmhsc-06-2019-005 [ Links ]

Mangcu, X. (2017). Shattering the myth of a post-racial consensus in South African higher education: "Rhodes Must Fall" and the struggle for transformation at the University of Cape Town. Critical Philosophy of Race, 5(2), 243-266. [ Links ]

Maylor, U., Roberts, L., Linton, K., & Arday, J. (2021). Race and educational leadership: The influence of research methods and critical theorising in understanding representation, roles and ethnic disparities. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 49(4), 553-564. [ Links ]

Mekoa, I. (2018). Challenges facing Higher Education in South Africa: A change from apartheid education to democratic education. African Renaissance, 15(2), 227-246. [ Links ]

Moopi, P., & Makombe, R. (2022). Coloniality and Identity in Kopano Matlwa's Coconut (2007). Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction, 63(1), 2-13. [ Links ]

Moorosi, P. (2021). Colour-blind educational leadership policy: A critical race theory analysis of school principalship standards in South Africa. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 49(4), 644-661. [ Links ]

Mortlock, M. (2015, October). Open Stellenbosch releases racism documentary. Eyewitness News. Retrieved from https://ewn.co.za/2015/08/22/Open-Stellenbosch-releases-racism-documentary. [ Links ]

Munoriyarwa, A. (2021). There ain't no rainbow in the 'rainbow nation': A discourse analysis of racial conflicts on twitter hashtags in post-apartheid South Africa. In M Perez-Escobar and J.M. Noguera-Vivo, Hate Speech and Polarization in Participatory Society (pp. 67-82). Routledge. [ Links ]

Nakajima, T. M., Karpicz, J. R., & Gutzwa, J. A. (2022). "Why isn't this space more inclusive?": Marginalization of racial equity work in undergraduate computing departments. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. 17(1), 27-39. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000383 [ Links ]

Ngoepe, K. (2016, February). Students clash over Tuks language policy. News24. Retrieved from https://www.news24.com/news24/students-clash-over-tuks-language-policy-20160218 [ Links ]

Pattman, R., & Carolissen, R. (Eds.). (2018). Transforming transformation in research and teaching at South African universities. African Sun Media. [ Links ]

Pietkiewicz, I., & Smith, J. A. (2014). A practical guide to using interpretative phenomenological analysis in qualitative research psychology. Psychological Journal, 20(1), 7-14. [ Links ]

Pirtle, W. N. L. (2022). "White people still come out on top": the persistence of white supremacy in shaping coloured South Africans' perceptions of racial hierarchy and experiences of racism in post-apartheid South Africa. Social Sciences, 11(2), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11020070 [ Links ]

Qutoshi, S. B. (2018). Phenomenology: A philosophy and method of inquiry. Journal of Education and Educational Development, 5(1), 215-222. [ Links ]

Ratele, K. (2021). Biko's black conscious thought is useful for extirpating the fear of whites deposited in black masculinity. Studies in Gender and Sexuality, 22(4), 311-321. [ Links ]

Roberts, B., Gordon, S., Chiumbu, S., Goga, S., Struwig, J., Ramphalile, M., & Van Rooyen, H. (2016). The longer walk to freedom: making sense of race relations. Retrieved from https://repository.hsrc.ac.za/handle/20.500.11910/9823. [ Links ]

Tuffour, I. (2017). A critical overview of interpretative phenomenological analysis: a contemporary qualitative research approach. Journal of Healthcare Communications, 52, 1-5. [ Links ]

Vincent, L. (2008). The limitations of 'inter-racial contact': stories from young South Africa. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 31(8), 1426-1451. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870701711839 [ Links ]

Walker, M. (2005). Race is nowhere and race is everywhere: Narratives from black and white South African university students in post-apartheid South Africa. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 26, 41-54. [ Links ]

Wesi, T. (2015 October 17). Stepping up and forward as a white student was imperative. Mail and Guardian. Retrieved from https://mg.co.za/article/2015-10-27-stepping-up-and-forward-as-a-white-student-was-imperative/ [ Links ]

Wertheim, S. S. (2014). From a privileged perspective: How White undergraduate students make meaning of cross-racial interaction (Doctoral dissertation, New York University). [ Links ]

Willig, C. (2013). Introducing qualitative research in psychology. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill Education. [ Links ]