Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

On-line version ISSN 2412-4265Print version ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.40 n.2 Pretoria Dec. 2014

HISTORIES OF CHRISTIANITY AND WAR

Between war and peace: The Dutch Reformed Church agent for peace 1990 -19941

Johan van der Merwe

Department of Church History and Church Polity, Faculty of Theology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The years between 1990 and 1994 can be described as some of the most violent years in the history of South Africa. Political turmoil en route to the first democratic election in 1994 brought the country to the brink of civil war. During these volatile times important role players emerged who helped to bring calmness and sanity to society. One of these important role players was the moderature of the Dutch Reformed Church. By engaging with the different role players and calling their members to calmness, the leadership of the church which was known for its biblical support of apartheid became an important agent of peace. This article gives an overview of the volatile 1990's with special focus on the role of General Constand Viljoen, a member of the Dutch Reformed Church and leader of the right-wing Afrikaners. It then describes the role of the moderature of the Dutch Reformed Church in mediating peace en route to the election of 27 April 1994. Interviews with leading role players as well as non-published church documents serve as important sources for this article.

Introduction

"I am going to let the dogs loose? "2 This statement of General Constand Viljoen on a decision he took in the week prior to the first democratic election in the history of South Africa in April 1994 describes how close the country came to civil war. But Reverend Freek Swanepoel, moderator of the General Synod of 1994 said about the same era: "We wanted to prevent blood."3 His statement is an indication of the role that the Dutch Reformed Church played in the prevention of a civil war before the election of 1994. On the day we remember the Marikana massacre4 of 2012 and in the year we celebrate 20 years of democracy in South Africa, it is important to remember the miracle of the first democratic election in South Africa and to celebrate important role players who choose peace instead of war. The aim of this article is to focus on the specific role that the moderature of the Dutch Reformed Church played in preventing civil war and ensuring a peaceful election in 1994. In order to do so it will firstly describe the volatile context of South Africa in the years 1990 to 1994 with specific focus on the role of General Constand Viljoen, a member of the Dutch Reformed Church. Secondly it will describe the role of the moderature of the Dutch Reformed Church before coming to a conclusion that the leadership of the church which was known for the biblical foundation of apartheid indeed played an important role to prevent bloodshed and civil war.

South Africa: 1990 - 1994

Violence

Giliomee and Mbenga (2007) describe the turbulent times of the nineties correctly when they say:

The government's lifting of the ban on the African National Congress (ANC) and other liberation and extra-parliamentary movements on 2 February 1990 triggered a surge of political activity. Mass meetings attended by multitudes, particularly to hear Nelson Mandela, freed on 11 February 1990, together with strikes, street protests, demonstrations and violence of all kinds ushered in a period of profound uncertainty and potentially dangerous instability.5

Although the core area of conflict was the KwaZulu-Natal area where battles between Inkhata and the ANC raged, shortly after 1990 the number of deaths outside Natal rose from 124 to 1888 which clearly indicates how violence spread through the whole country.6 It is not possible to fully understand and describe the full extent of what was happening in the country. Important markers can however be revisited in order to paint the darkening picture of a country spiralling into the abyss of civil war. These markers were identified due to the fact that each of them had a definite influence on the road to 1994. They also challenged the churches of South Africa in a very specific way to speak out and confront the situation in South Africa.

The first important marker was Operation Vula. Leaders of the ANC approved this operation headed by Mac Maharaj in 1986.7 The aim of the operation was to build an underground network in the country, infiltrating arms and staging an insurrection should negotiations fail.8 The plan was implemented in 1990. Although negotiations, which were under way, led to the Groote Schuur Minute, "facilitating the release of political prisoners, the return of exiles and the amending of security legislation",9 the ANC's suspension of the armed struggle,10 and an "all party congress" to negotiate the route to a constituent assembly,11 violence still spiralled out of control. Sparks remarks correctly that after the collapse of CODESA: "The centre of political gravity within the ANC alliance shifted in mid 1992 to its militant wing."12 Two weeks after the collapse of CODESA 2 a special ANC strategy conference decided to launch a campaign of "rolling mass action" - a continuous series of strikes, boycotts and street demonstrations.13 This decision was strengthened by Operation Vula and set the scene for increased violence.

The second important marker was the Boiphatong massacre, an event that shook South Africa to the core. On the night of 17 June 1992, a posse of armed Zulus crept out of a migrant worker's hostel near a township called Boiphatong and "in an orgy of slaughter hacked, stabbed and shot 38 people to death in their homes". Among the dead were a nine- month-old baby, a child of four, and twenty four women, one of them pregnant. The outrage of Boiphatong, coming on top of the collapse of CODESA strengthened the militant wing of the ANC and brought South Africa closer to the brink of civil war and revolution.14

The third important maker was the result of the so-called "Leipzig option". It referred to the mass demonstrations in the streets of Leipzig and other cities which toppled Honecker's East German regime three years before.15 On 23 August ANC leaders accepted a discussion paper drafted by a group of radicals suggesting that the homelands Ciskei, Bophuthatswana and KwaZulu be targeted for mass action.16 This decision led to another shocking incident of violence in Bisho, Ciskei. The plan was to stage a march on Ciskei's capital Bisho and to occupy it by a people's assembly. On 7 September 1992 things went horribly wrong and troops opened fire on the marchers, killing 28 and wounding more than two hundred.17 It was further proof that the violence was spiralling out of control. Both President De Klerk and Mr. Mandela realised it and when De Klerk invited Mandela to a summit meeting to find a way to end the spiral of violence, Mandela responded positively. Sparks comments on this by saying: "Once again, South Africa's black and white leaders had to stare into the abyss in order to recognize their mutual dependency. If violence went out of control, both would be losers."18 The summit meeting, held in Johannesburg on 26 September 1992 would be the turning point. President FW de Klerk commented on the importance of this meeting: "We got together to start writing the next chapter in the negotiation saga."19

The fourth important marker was the assassination of Chris Hani. He was shot by a Polish immigrant Janusz Walusz on the morning of 10 April 1993. Hani was General Secretary of the Communist Party and the most charismatic of the black leaders.20 Sparks is correct when he says: "The news of Hani's assassination hit South Africa like a thunder clap. Anyone wanting to ignite an inferno of rage in the black community could not have chosen a better target."21 De Klerk reflects on the event: "1 immediately realised that this could lead to a serious crisis."22 The following quote from Mr. Nelson Mandela's speech that night on television says it all:

Tonight I am reaching out to every single South African, black and white, from the very depths of my being. A white man, full of prejudice and hate, came to our country and committed a deed so foul that our whole nation now teeters on the brink of disaster. A white woman, of Afrikaner origin, risked her life so that we may know, and bring to justice, this assassin. The cold- blooded murder of Chris Hani has sent shock waves throughout the country and the world ... Now is the time for all South Africans to stand together against those who, from any quarter, wish to destroy what Chris Hani gave his life for - the freedom of all of us.23

The fifth important marker was the so-called "Battle for Bob", In the months leading up to the election it looked as if the political centre was unable to hold.24 Lucas Mangope, President of Bophuthatswana resisted the homeland's reincorporation in South Africa. The situation in Mafikeng, capital of Bophuthatswana spiralled out of control after the ANC initiated mass action. On 11 March 1994 an armed AWB mob entered Mmabatho as part of an "army" to assist Mangope, "blazing away on innocent bystanders, seizing cameras from journalists and beating them. At a roadblock soldiers of Bophuthatswana who turned against Mangope and the AWB exchanged shots. Three white men occupying the last car in the convoy were shot at point black range".25 The execution was screened live on television during the six o'clock news.

These markers clearly indicate the extent of what was happening in the country. This was however only one side of the coin. On the other side, leaders of different communities tried their utmost to prevent war.

Prospects of a disrupted election

While black violence was threatening to send South Africa down what Sparks calls "the Sarajevo road"26 another threat was developing from the right-wing Afrikaner group. General Constand Viljoen retired as chief of the National Defence Force in 1985. Sparks describes him as an "enigmatic figure who stepped out of the obscurity of a bushveld cattle ranch to become an instant hero to the wild men of the right".27 General Viljoen appeared on the scene in a time "when their blood was up in the overcharged atmosphere following the assassination of Chris Hani, the arrest of Conservative party members for murder and a serious of random attacks on white farmers".28 On 7 May 1993, fifteen thousand farmers, some armed to the teeth, gathered in a rugby stadium in the Western Transvaal town of Potchefstroom. After shouting down the deputy minister of Agriculture, Tobie Meyer, they called for General Viljoen, who was sitting in the crowd to address them.29 Although Viljoen, who did not go with the intention to deliver a speech or become leader of the group, addressed the crowd when he was called upon saying that he did not trust De Klerk and that he believed that the ANC was stiil pursuing a revolutionary strategy.30 He believed that the government should stop all negotiations and first deal with the security problem in the country. Sparks describes the mood at the meeting: "'Lead us! Lead us!' the crowd roared and Viljoen found himself elected by acclamation to a leadership role." His assessment is correct when he says that "the election of General Viljoen was to prove critical in the delicate balance between forces of violence and of reason in the white right."31 This is confirmed by President FW de Klerk when he states: "I identified Viljoen as a key figure in the right wing alliance."32 Although Viljoen states clearly that at that time he was not interested in fighting, it became an option as the situation in South Africa had changed.33

"Uncertainty about what Viljoen might be planning would constantly be in the background while negotiations continued."34 Viljoen and his followers joined the Afrikaner Volksfront, a coalition of right-wing organisations, which all rejected participation in a democratic election and demanded an Afrikaner Volkstaat35 The Volksfront wanted a white state. A Volksfront council was formed with Ferdi Hartzenberg, leader of the Conservative party as chairman. The Volksfront also appointed a directorate of four retired generals whose task it was to form a "Boer people's army".36 Tension soon arose between Hartzenberg and Viljoen when the Volksfront withdrew from the negotiations. According to Viljoen, that left only the military option - and he emphasises - "I did not believe in that."37 Sparks is correct when he says: "He (Viljoen) and Hartzenberg finally settled on an uneasy compromise: The Conservative Party would stay out of the negotiations, but the Volksfront generals would begin direct bilateral talks with the ANC outside the negotiating Council."38 More than twenty meetings followed which led to a memorandum of agreement which would ensure self-determination to the boerevolk.39

At the beginning of 1994, negotiations stalled. Meetings were postponed and priorities changed. Sparks quotes Braam Viljoen, twin brother of General Constand Viljoen saying: "We couldn't pin anyone down and morale in the conservative movement slumped."41 General Viljoen felt strongly that he had to have a written agreement from the ANC before the elections. Princeton Lyman, United States ambassador to South Africa reflects on what happened, as follows:

The final agreement was ready by April 12, but the ANC kept postponing the signing ceremony. Viljoen grew suspicious. 'This gave me the impression that the ANC was playing us for the fool and that they were trying to push me to the 27,h and then put me in a very difficult position, hoping that 1 would accept the fact'.42

What happened next confirms the fact that Viljoen and his army of 50 000 was on the brink of disrupting the election. In Viljoen's own words: "There wouldn't have been an election."43 On 16 April 1994, after a meeting with his generals at De Deur, General Viljoen phoned Lyman telling him: "I am going to let the dogs loose."44 Lyman reflects as follows:

Postponement of the signing had resurfaced in Viljoen all the deep suspicions about the ANC, indeed about the whole transitional process as far as the protection of his people were concerned. What Viljoen now meant by letting the dogs loose was that he would disrupt the election. A military establishment of an Afrikaner volkstaat was no longer possible, he knew, 'but a disruption of the election would be easy'.45

General Viljoen had a gentleman's agreement with Lyman that he would phone him before he went to into action.46 Lyman asked for time to call Viljoen back and immediately phoned Yusuf Salojee, chief aide of Thabo Mbeki at his office.

I explained the situation, that Viljoen felt he was being betrayed, that all the work that had gone into negotiating an agreement with Viljoen, in breaking down right-wing resistance, was at risk. I knew that the ANC was not trying to fool Viljoen, but delaying the signing ceremony created that impression. In a few minutes Salojee called back. The signing ceremony was set for April the 23th.47

General Viljoen reflects on the call that he received from Lyman telling him about the decision: "I realized that I had to call off the disruption of the election. One of the most difficult moments of my whole life was to tell my commanders to stand down. They were ready for action and I had to tell them that it is not going to happen."48 This remark of General Viljoen confirms how near the disruption of the elections was. It also shows what a big miracle of the first democratic elections was.

The miracle did not happen all by itself. Church leaders of the Dutch Reformed Church, the church responsible for the biblical foundation of the notorious policy of apartheid, played a major role. This was confirmed by Mr. Nelson Mandela when he addressed the general Synod of the Dutch Reformed Church in October 1994. He said:

I refer you to the constructive role which the leadership of the DRC played during the stormy times in the approach to the election of 27 April 1994. Your willingness to reprimand some of the members of your own church against racism and violence played an important part in the miracle of South Africa's peaceful transformation to democracy. You are an integrate part of the special witness which South Africa bears in a world where so much violence and intolerance still rules (own translation)49

The role of the church leaders in the Dutch Reformed Church

The leadership of the Dutch Reformed Church unquestionably played a major role during the troublesome times of 1990 to 1994. The scene was set for their role during the church conference of 1990 which was held in Rustenburg.

The Rustenburg church conference: 1990

In December 1989, State President FW de Klerk in his Christmas message made an appeal to the churches in South Africa to formulate a strategy 'conductive to negotiation, reconciliation and change for the situation in South Africa'.50 A steering committee was appointed under the leadership of Dr. Louw Alberts to organise a conference of church leaders from across the spectrum of Christian churches in South Africa to "rediscover its calling and to unite Christian witness in a changing South Africa".51 The conference was held from 5 to 9 November 1990 at the Hunters Rest Hotel outside Rusten» burg.52 The delegation of the Dutch Reformed Church consisted of Prof. PC Potgieter, moderator of the General Synod of the church, Dr. P Rossouw, Dr. DJ Hattingh and Dr. FM Gaum. Prof. JA Heyns and Prof. WD Jonker were present as speakers.

During Jonker's address he made the confession that resounded throughout the world within hours. He said:

I confess before you and before the Lord, not only my own sin and guilt, and my personal responsibility for the political, social, economical and structural wrongs that have been done to many of you, and the results of which you and our whole country are still suffering from, but vicariously I dare also do that in the name of DRC of which I am a member, and for the Afrikaner people as a whole. 1 have the liberty to do just that, because the DRC at its latest synod has declared Apartheid a sin and confessed its own guilt of negligence in not warning against it and distancing itself from it long ago.53

After Jonker's address, Archbishop Desmond Tutu reacted by saying:

Prof. Jonker made a statement that certainly touched me and I think touched others of us when he made a public confession and asked to be forgiven. I believe that I certainly stand under pressure of God's Holy Spirit to say that, as I said in my sermon that when confession is made, then those of us who have been wronged must say 'We forgive you', so that together we may move to the reconstruction of our land. That confession is not cheaply made and the response is not cheaply given.54

Like so many times before, this special moment was marred by what happened next. From all over South Africa messages and telegrams were received to thank Jonker, but there were also those who asked the question: "Who gave him the right to confess on behalf of them and the Afrikaner people?" The previous State President PW Botha was one of the first to phone Prof. Potgieter to object to the confession.55 Prof. Potgieter recalls that Botha went raging on for about ten minutes before he (Potgieter) could get a word in. Potgieter asked the furious Botha to wait for the official declaration of the Dutch Reformed Church.56 The next morning Potgieter was asked to make a statement about the issue. He said that there are delegates who doubt if the confession was really genuine with respect to the position of the Dutch Reformed Church. He then continued by saying

The delegates of the DRC want to state unambiguously that we fully identify ourselves with the statements made by Prof. Jonker on the position of the church. He has in fact precisely reiterated the decision made by our General Synod in Bloemfontein recently. We would like to see this decision of the synod as the basis of reconciliation with all people and all Churches.57

After the declaration was televised during the eight o'clock news, Botha phoned Potgieter again. This time he raged on for more than fifteen minutes attacking Potgieter and the delegation and telling him that they had no right to make such a confession. Prof. Potgieter at one stage told the ex-President: "Mr. Botha, this discussion is going nowhere" and put the phone down in Botha's ear.58 Although the confession of Rustenburg put the Dutch Reformed Church in a position to play a serious role in preventing war, Botha's reaction also showed that it would not be all plain sailing. A protest meeting organised by Reverend Kobus Potgieter59 which took place on 1 December 1990 in Pretoria confirmed this fact.60 The resistance from the conservative members of the church however did not stop the leadership of the Dutch Reformed Church to do what they believed the role of church should be. This is best illustrated by a declaration which was released after a multi-church conference in November 1993 which was held in Pretoria. Mr. Thabo Mbeki was the main speaker. Paragraph one of the declaration stated clearly: "The Church of Jesus Christ has a message that rises above party politics and its differences. It is a message of conversion, salvation, reconciliation and peace. The church must make this message visible through its words and deeds."61 The fact that the leadership of the Dutch Reformed Church identified with this role, led to a second important development.

Engaging with Mr. Nelson Mandela

The second important development was various meetings between Mr. Nelson Mandela and the executive of the Dutch Reformed Church between 1990 and 1994. They met four times - three times in the synodical centre in Pretoria and once in Luthuli house.62 According to Gaum, all the meetings between 1990 and 1994 took place in a good spirit and made a constructive contribution to peace in the country.63 Gaum recalls:

The discussions between Mr. Mandela and the executive of the moderature focused on two specific aspects of the violence in the country - violent resistance from the far right Afrikaners (AWB) and violent protests by the ANC and its partners to overthrow the National Party 'regime' of FW de Klerk. Notwithstanding the negotiations of CODESA 1 and CODESA 2 there were rumours that certain factions in the ANC had plans to take power by military force. Rumours about a 'Third Force' which was used by the government to instigate violence between the ANC and Inkatha in KwaZulu-Natal, were also part of the discussions 64

The first meeting was held on 30 May 1991. During this meeting, Mr. Mandela spoke about the ongoing violence between the ANC and the Inkatha Freedom Party. He asked the church leaders to speak to Mr. Buthelezi of Inkatha, requesting him to put pressure on his followers to stop carrying traditional weapons when taking part in marches.65 During the second meeting which took place on 26 April 1993, Mr. Mandela was very concerned about the right-wing faction among Afrikaners, and specifically asked the executive to try and persuade them to take part in the negotiation process. After the meeting, the executive asked Prof. JA Heyns to make contact with General Constand Viljoen, who at that stage was leading the right-wing faction.66 Viljoen recalls that this meeting did not go well and that he decided not to meet with Heyns again.67 The third meeting took place on 12 November 1993 against the background of escalating violence and the growing threat of General Constand Viljoen and conservative Afrikaners. An in-depth discussion of more than two hours took place on the violence in the country. The moderature made specific mention to Mr. Mandela about the negative influence some ANC leaders such as Pieter Mokaba had on the Afrikaner population with his "Kill the boer, kill the farmer" song. Mandeia reacted by saying that the song did not reflect official ANC policy and that the ANC was handling the matter internally.68 During the meeting on 25 January 1994 it was Mr. Mandela's turn to specifically ask the church leaders to persuade General Viljoen to come to the negotiating table and take part in the election.69 At that stage Viljoen was ready to disrupt the coming election with military force. "I had the pistol in my hand."70 He also requested that the church must ask its members, working in state departments, not to leave because they had an important role to play after the election in April. This proves that the leadership of the Dutch Reformed Church played an important role in mediating a peaceful transformation to democracy. The relationship of trust between Mandela and the church leaders of the Dutch Reformed Church made them important actors in the grand drama that was playing out in South Africa. Reverend Freek Swanepoel, who became moderator of the Dutch Reformed Church in 1994, confirms this by saying: "Mr. Mandela was a fine strategist who knew that the Dutch Reformed Church, being the largest of the white Afrikaans churches, had a big influence on her members. By using the church as agent for reconciliation, which is her calling, he succeeded in promoting peace in a country on the brink of civil war."71 This is also confirmed by a letter which Mr. Mandela wrote to Prof. Pieter Potgieter, outgoing moderator in 1994 in which he thanked him for his contribution "over these years of transition and turbulence in the midst of transformation".72 The visit and speech by Mr. Nelson Mandela during the General Synod of the Dutch Reformed Church in Pretoria 199473 serves as further confirmation of the contribution which the relationship between Mr. Mandela and the executive of the Dutch Reformed Church made during volatile times of the early 1990's. Mr. Mandela was the first State President to ever address a synod of the Dutch Reformed Church.

Discussions with other political role players

The leadership of the Dutch Reformed Church did not only speak to Mr. Mandela during 1990 to 1994. The third important development was the fact that they also met with other important political role players in the country.

FW de Klerk and the leadership of the National Party

The executive of the moderature Dutch Reformed Church met President FW de Klerk for the first time after the Church conference in Rustenburg on 26 November 1990. At this meeting the church leaders gave personal feedback about proceedings during the church conference. The confession of Prof. Willie Jonker and the reaction from right-wing Afrikaners was discussed. President De Klerk was also briefed on the coming protest meeting that was organised for 1 December 1990. The decisions of the General Synod concerning human rights were also conveyed to the State President. This meeting was followed by several more meetings in November 1991, March 1992, August 1993 and November 1993. Violence in the country, progress in the negotiation process, and the position of the Afrikaner was discussed. Church leaders also informed President De Klerk of their meetings with right-wing Afrikaners and Mr. Nelson Mandela. It is clear from the content of the meetings that the church leaders saw themselves in a mediatory role between the different political groups in the country, but more so among white Afrikaners who were severely divided by the referendum of 1992. The division not only influenced the political landscape, but had serious implications for the church itself. The meetings with Mr. De Klerk would also lead to an important meeting with the leadership of the National Party.

On Tuesday, 10 August 1993 the executive met with the leaders of the National Party in Cape Town. Although violence was on the agenda, the church leaders also asked how human rights would be protected in the new constitution; whether the National Party was committed to 27 April 1994 as election date; what the National Party's point of view was on self-determination, and what the position of Afrikaans as language would be in the new political dispensation.74 It is clear from the above, that the church leaders saw themselves as mouth pieces of their members as these questions were the main concerns of many of the white Afrikaans-speaking people in the country.

General Constand Viljoen and the Volksfront

Important and serious discussions were also held with leaders from the right-wing Afrikaner group. The fact that General Constand Viljoen was a member of the Dutch Reformed Church and a secundus member of the moderature made it easier for the leadership of the church to engage with him. A letter from Prof. Pieter Potgieter that was faxed to the executive of the Dutch Reformed Church on 29 October 1993 about discussions between him and General Constand Viljoen serves as an example. The letter calls for an important telephone meeting on 31 October 1993 "to try and prevent a possible crisis which could have serious consequences".75 In the confidential letter Potgieter wrote:

From a discussion which I had with General Viljoen and others, it is clear that the need for self-determination to Afrikaners is VERY strong. He and his colleagues76 feel that their point of view is being ignored by the negotiations process and that the Dutch Reformed Church can play an important role to ensure that justice is done.77

The proposal that was accepted by the meeting sheds more light on how serious Potgieter took Viljoen and how serious the situation was. It started with a call on everybody concerned with the negotiations to take serious note of the desire of groups in the South African society who wanted self-determination on a regional basis, it also called on all parties who wanted self-determination not to withdraw from the negotiations and not to promote a climate of violence.78 It is clear from this proposal that General Viljoen told Prof. Potgieter in no uncertain terms that he "had the pistol in his hand" and that he would disrupt the elections if his demands were not met. Although Viljoen stated clearly that he was "not for war" it certainly became an option as the end of 1993 drew near.79 Potgieter understood this clearly and acted by calling a special meeting of the executive. Although Viljoen denies that the church leaders played an important part in convincing him not to go to war,80 Gaum states: "Mr. Mandela asked the church leaders to convince Viljoen to take part in the negotiations. The general had, in several meetings with the executive obstinately refused, but eventually decided to change his mind."81 It would be assumptive to say that the leaders of the Dutch Reformed Church persuaded Viljoen, but that they played an important part, cannot be denied. This is confirmed by a letter from Viljoen that was published in Die Kerkbode on 18 March 1994. General Viljoen wrote: "Thank you for your reasonable and balanced point of view in your open letter to the State President which was published in the editor's column of 4 February 1994. Your point of view is an example to me of what a church is supposed to do" (my translation).82

Discussions between the church leaders and leaders from the conservative side did not always end well. A meeting with Dr. AP Treumicht, former leader of the Conservative Party ended abruptly early in 1991 when Dr. Treunicht stormed out of the meeting. Gaum reflects on this: "Treumicht was obstinate about his point of view and proclaimed his dissatisfaction with the decisions which the Dutch Reformed Church took at its General Synods since 1986."83 This led to a direct confrontation between him and Prof. Johan Heyns, during which Treumicht got up and left the meeting.

Members of the executive also visited Mr. Eugene Tereblanche, leader of the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB)84 on his farm near Venters-dorp. The sole purpose of the meeting was to try and persuade Mr. Tereblanche that violence was not an option and that he and the AWB could ignite an inextinguishable fire with their war talk. 85 That this discussion made no impression on Tereblanche is confirmed by the so-called "Battle of Bop" where three AWB members were executed.

Conclusion

"We wanted to prevent blood."86 This remark by Reverend Freek Swanepoel clearly states the intent with which the leadership of the Dutch Reformed Church operated in the years 1990 to 1994. Did they succeed? Two facts confirm the important role that the leadership of the church played: The first is the fact that the "dogs were not let loose".87 Although other important factors also played a role in General Constand Viljoen's decision not to disrupt the 1994 election, the role of the leadership of the Dutch Reformed Church cannot be ignored. This statement directly links up with the second confirmation - that of Mr. Nelson Mandela during the General Synod of 1994, Mr. Mandela was invited to attend the opening of the synod, but was out of the country at that time. On his arrival back in South Africa, he responded on an invitation from Dr. Frits Gaum that he not only wanted to visit the synod, but that he also wanted to address the synod. During his address, he gave recognition to the role which the leaders of the Dutch Reformed Church played in the years 1990 to 1994. This was further confirmed by the last President of the apartheid era, FW de Klerk when he said to Die Kerkbode that he was grateful towards the leaders of the Dutch Reformed Church for the mediating role which they played during the troublesome times.88 The church which became known world-wide for its biblical support of the notorious policy of apartheid, played an important role in the "bloody miracle" - said by none other than Mr. Nelson Mandela.

Works consulted

Alberts, Louw and Chikane, Frank (eds.) 1991. The Road to Rustenburg. Cape Town: Struik Christian books. [ Links ]

De Klerk, FW. 1998. FW de Klerk - Die Outobiografie. Kaapstad: Human & Rousseau. [ Links ]

Die Kerkbode 1993. Ander soort noodtoestand indien nodig - President De Klerk. 20 Augustus. [ Links ]

Die Kerkbode 1994. Generaal Viljoen sê dankie. 18 Maart. [ Links ]

Du Toit, F., Hofmeyr, JW., Strauss, PJ. & Van der Merwe, JM. 2002. Moeisame pad na vernuwing; Die NG Kerk se pad van isolasie en die soeke na nuwe relevansie. Bloemfontein: CLF Drukkers. [ Links ]

Els, CW. 2008. Reconciliation in South Africa: The role of the Afrikaans churches. Unpublished PhD. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Gaum, FG. 2014. Persona! correspondence. 20 May. [ Links ]

Giliomee, H. 2004. Die Afrikaners - 'n Biografie. Kaapstad: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Giliomee, H. & Mbenga, B. 2007. New history of South Africa. Cape Town: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Jonker, W. 1998. Selfs die kerk kan verander. Kaapstad: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Lyman, PN. 2002. Partner to history: The U.S. role in South Africa's transition to democracy. Washington, D.C: United States Institute of Peace Press. [ Links ]

Mandela, NM. 1993. Letter to GeneraI C. Viljoen. Personal collection, Johan M van der Merwe: Pretoria. [ Links ]

Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk 1993. Algemene Sinodale Kommissie 5-6 November. Bylaag. [ Links ]

Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk 1994. Handelinge van die negende Algemene Sinode: Pretoria. [ Links ]

Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk 1991. Notule van die Dagbestuur van die Algemene Sinodale Kommissie. Pretoria. 13-14 Maart. [ Links ]

Sparks, A. 1995. Tomorrow is another country - The inside story of South Africa's negotiated settlement. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers. [ Links ]

Interviews

Potgieter, PC. 4 November 2014. Wildernis.

Swanepoel, F. 29 May 2014. Cape Town.

Viljoen, C. 7 June 2014. Ohrigstad.

1 Paper delivered at the Church History Society of Southern Africa on 16 August 2014.

2 Interview: General Constand Viljoen, 7 June 2014

3 Interview: Reverend Freek Swanepoel, 29 May 2014.

4 The Marikana massacre took place on 16 August 2012 when police opened fire on striking mine workers outside Marikana resulting in the death of 44 people.

5 Herman Giliomee and Bernard Mbenga, New History of South Africa (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2007), 396

6 Giliomee and Mbenga, 397

7 Giliomee and Mbenga. 399.

8 Gliomee and Mbenga, 399.

9 Alister Sparks, Tomorrow is another country - The inside story of South Africa 's negotiated settlement, (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers, 1995),96.

10 Frederick W De Klerk. FW de Klerk - Die Outobiografte. (Kaapstad: Human & Rousseau, 1998), 222.

11 Sparks. 100.

12 Sparks, 106.

13 Sparks, 108.

14 De Klerk. 257.

15 Sparks, 114.

16 Sparks, 114.

17 Sparks, 117.

18 Sparks, 118.

19 De Klerk, 270.

20 Sparks, 146.

21 Sparks. 146.

22 De Klerk, 293.

23 Sparks. 147.

24 Giliomee and Mbenga, 400.

25 Sparks, 165.

26 Sparks, 139.

27 Sparks, 154. Sparks has the date as 1984. Viljoen confirmed in an interview on 7 June 2014 that it was in fact 1985.

28 Sparks, 155.

29 Sparks, 155.

30 Interview: General Constand Viljoen on 7 June 2014.

31 Sparks, 155.

32 De Klerk, 328.

33 Interview: General Constand Viljoen, 7 June 2014.

34 Giliomee and Mbenga, 402.

35 Hermann Giliomee, Die Afrikaners - 'n Biografie. (Kaapstad: Tafelberg, 2004). 607.

36 Sparks, 156.

37 Interview': Genera! Constand Viljoen, 7 June 2014.

38 Sparks, 156.

39 Sparks, 159.

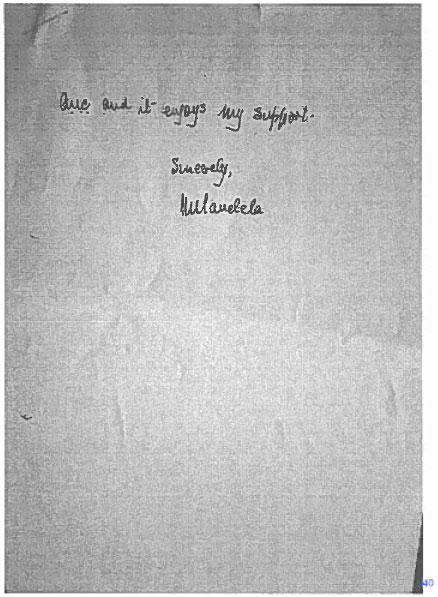

40 Handwritten letter from Mr. Nelson Mandela to General Constand Viljoen confirming the agreement, 21 December 1993.

41 Sparks, 159.

42 Princeton N Lyman, Partner to history: The U.S. role in South Africa's transition to democracy. (Washington, D.C: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2002), 178.

43 Interview: General Constand Viljoen, 7 June 2014.

44 Interview: General Constand Viljoen, 7 June 2014.

45 Lyman, 178.

46 Interview: General Constand Viljoen, 7 June 2014.

47 Lyman, 178.

48 Interview: General Constand Viljoen, 7 June 2014.

49 "Ek verwys graag na die konstruktiewe rol wat die leierskap van die NG Kerk gespeel het tydens die onstuimige tye met die aanloop tot die verkiesing van 27 April 1994. U bereidwilligheid om ook sommige van u eie kerklidmate te maan teen rassisme en onverskillige geweldspraatjies, het 'n belangrike bydrae gelewer om die wonderwerk van Suid-Afrika se vreedsame oorgang tot demokrasie moontlik te maak. U is 'n integrale deel van die besondere getuienis wat Suid-Afrika vandag lewer in 'n wéreld waarin daar nog soveel geweld en onverdraagsaamheid heers". Handelinge van die Algemene Sinode 1994, p 536.

50 Flip Du Toit, Johannes W Hofmeyr, Piet, J Strauss en Johan M van der Merwe, Moeisame pad na vernuwing: Die NG Kerk se pad van isolasie en die soeke na mnve reivansie, (Bloemfontein: CLF Drukkers, 2002), 105.

51 Louw Alberts and Frank Chikane (eds), The Road to Rustenburg, (Cape Town: Struik Christian Books, 1991), 15.

52 Du Toit, Hofmeyr, Strauss & Van der Merwe, 105.

53 Alberts & Chikane (eds), 92.

54 Alberts & Chikane (eds), 96.

55 Christiaan W Els, Reconciliation in South Africa: The role of the Afrikaans churches, (University of Pretoria, Unpublished PhD, 2008), 97.

56 Interview: Prof Pieler Potgiter, 4 November 2013.

57 Willie Jonker, Selfs die kerk kan verander. (Kaapstad: Tafelberg, 1998), 207.

58 I nterview: Prof Pieter Potgieter, 4 November 2013.

59 Ds Kobus Potgieter was moderator of the Dutch Reformed Church from 1982 -1986.

60 Algemene Sinodale Kommissie van die Ned Geref Kerk: Dagbestuur, 13-14 Maart 1991.

61 Algemene Sinodale Kommissie van die Ned Geref Kerk: Dagbestuur, 25 Januarie 1994, Bylaag 2.

62 Personal correspondence with Dr FM Gaum, I. Gaum, 1.

63 Gaum, 2.

64 Gaum, 2.

65 Bylaag 2/1, Dagbestuur van die Algemene Sinodale Kommissie 5-6 November 1991.

66 Bylaag 2/1, Dagbestuur Algemene Sinodale Kommissie.

67 Interview: General Constand Viljoen, 7 June 2014.

68 Bylaag 2/1, Dagbestuur Algemene Sinodale Kommissie.

69 Gaum, 3.

70 Viljoen: Interview 7 June 2014, " Ek het die pistool in my hand gehad.'*

71 Interview: Reverend Freek Swanepoel, 29 May 2014.

72 Johan M van der Merwe, Personal collection. Copy of Letter from Mr. Nelson Mandela to Prof. Pieter Potgieter.

73 Mr. Mandela visited the synod on 13 October 1994.

74 Letter, Bylaag tot Algemene Sinodale Kommissie 5- 6 Nov 1993.

75 Letter, Bylaag tot Algemene Sinodale Kommissie 5- 6 Nov 1993.

76 Viljoen was accompanied by some of his generals,namely, Genls. Groenewald, Bischoff and Neethling.

77 Letter, Bylaag tot Algemene Sinodale Kommissie 5- 6 Nov 1993.

78 Letter: Gaum, 3.

79 Interview: General Viljoen, 7 June 2014. See also 1.2 of this article.

80 Interview: General Viljoen, 7 June 2014.

81 Letter: Gaum. 4.

82 Generaal I Viljoen sè dank ie, Die Kerkbode 18 Maart 1994, p7.

83 Letter: Gaum, 2.

84 Translated as Afrikaner Resistance Movement.

85 Letter: Gaum, 4.

86 Interview: Reverend Freek Swanepoel, 29 May 2014.

87 Interview: General Constant Viljoen , 7 June 2014.

88 "Ander soort noodtoestand indien nodig - President De Klerk " Die Kerkbode 20 Augustus 1993, pl.