Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.33 Pretoria 2019

https://doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2018/n33a2

ARTICLES

A nation under our feet: Black Panther, Afrofuturism and the potential of thinking through political structures

Bibi BurgerI; Laura EngelsII

IDepartment of Afrikaans, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa bibi.burger@up.ac.za (ORCHID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9483-6671)

IIDepartment of Dutch Literature, University of Ghent (Ghent Centre for Afrikaans and the Study of South Africa), Ghent, Belgium Laura.Engels@UGent.be

ABSTRACT

In this article, the focus is on Black Panther: a nation under our feet, a comic book series written by American public intellectual Ta-Nehisi Coates. The point of departure is Coates's idea of 'the Mecca', a term he uses in his earlier non-fiction. It refers to a space in which black culture is created in the shadow of collective traumas and memories. We argue that in a nation under our feet the fictional African country of Wakanda functions as a metaphorical Mecca. This version of Wakanda is contextualised in terms of the aesthetics of Afrofuturism and theories on the influence of ideology in comic books. The central focus of the article is how this representation of Wakanda questions the idea of a unified black people and how Wakanda, like the real world Meccas described by Coates, display internal ideological and political struggles among its people. We argue that the various characters in a nation under our feet represent different and conflicting ideological positions. These positions are metaphors for real world political views and in playing out the consequences of these ideologies, Coates explores African and global political structures without didactically providing conclusive answers to complex issues.

Keywords: A nation under our feet; Afrofuturism; Black Panther; comic books; ideology; social criticism; Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Introduction

In (American public intellectual) Ta-Nehisi Coates's (2015:19) Between the world and me critiques essentialist notions of race, writing: ' ... I knew that I wasn't so much bound to a biological "race" as to a group of people, and these people were not black because of any uniform color or any uniform physical features. They were bound because they suffered under the weight of the [American] Dream'. He celebrates what he calls 'The Mecca' - black culture created in (and in spite of) 'the shadow of the murdered, the raped, the disembodied' (Coates 2015:120). Ta-Nehisi Coates (2015:40-41) recalls first encountering the Mecca while studying at the predominantly black Howard University and describes the diversity present in black culture at Howard as, 'like listening to a hundred different renditions of "Redemption Song," each in a different color and key'.

Upon first realising that conflict exists within this Mecca, that it is not 'a coherent tradition marching lockstep but instead factions, and factions within factions', Coates (2015:46) felt confused and disillusioned. Eventually, however, he learned to embrace the contradictions and conflict, 'The gnawing discomfort, the chaos, the intellectual vertigo was not an alarm. It was a beacon' (2015:52).

In Coates's first memoir, The beautiful struggle (2008), which is focused on his father, he also uses the term "The Mecca". He describes his father as a

conscious Man. [...] Weekdays he scooted out at six and drove an hour to the Mecca, where he guarded the books and curated the history in the exalted hall of the Moorland-Springarn Research Center (Coates 2008:12-13).

Here "The Mecca" refers to the archives in the Research Center. There, his father becomes obsessed with republishing books which were banned from the collective memory, written by black "seers", people of colour who wanted to (re)tell history. His father made it the quest of his life to share this alternative knowledge.

In the essays collected in We were eight years in power: An American tragedy (2017), Coates on occasion characterises black separatism as inherently conservative even when it is espoused by those on the political Left, because it is based (like other conservative ideologies) on the notion that things were better in the past (see Coates 2017:26). In an essay on Michelle Obama, however, he again explores the allure of a community of only black people, while also noting its disadvantages,

I came up in segregated West Baltimore. I understood black as a culture - as Etta James, jumping the broom, the Electric Slide. I understood the history and the politics, the debilitating effects of racism. But I did not understand blackness as a minority until I was an "only," until I was a young man walking into rooms filled with people who did not look like me. In many ways, segregation protected me - to this day, I've never been called a nigger by a white person, and although I know that racism is part of why I define myself as black, I don't feel that way, any more than I feel that the two oceans define me as American. But in other ways, segregation left me unprepared for the discovery that my world was not the world (Coates 2017:52; emphasis in original).

In our paper, we argue that in writing for Marvel's Black Panther, Coates solves this problem of the need for a completely black space in which to grapple with certain issues while not resorting to conservative politics. He does this by utilising the fictional country of Wakanda as a symbolic Mecca in which various ideological and philosophical debates can be played out metaphorically. In this way, Coates (in collaboration with artists Brian Stelfreeze, Chris Sprouse and Karl Story, and colour artist Laura Martin)1engages with a tradition within Afrofuturism of imagining Afrocentric spaces, societies and futures. Because Wakanda is fictional, it can be conceptualised in a way appropriate for the Afrocentric exploration of ideological conflicts. In keeping with Coates's criticism of a conservative idealisation of the past, Wakanda is not romanticised and is rather represented as an extremely complex society (Narcisse 2016b:[sp]).

In the next sections, we situate the representation of the various conflicting ideological forces in a nation under our feet (henceforth ANUOF) in terms of traditions within Afrofuturism and comic books. Thereafter, we discuss the history of Black Panther, as well as (the current Black Panther in ANUOF) T'Challa's various antagonists and the ideological positions they could be said to represent. This includes Zenzi's power to bring people's emotions to the fore as symbolic of populism, Tetu's violent defence of his ecological and spiritual worldview, The Midnight Angels' radical feminism and the philosopher Changamire's pacifist anti-monarchism. We will conclude the discussion by also analysing T'Challa's collaboration with his sister, Shuri, who goes through a process that could be described as a spiritual initiation in the Djalia (Plane of Wakandan Memory). She emerges from this plane, a better leader, her belief in monarchy rooted in knowledge of Wakandan history and mythology (Coates, Sprouse, Story & Martin 2016:90).

Afrofuturism

"Afrofuturism" is a term widely used in genre criticism. When it is used to refer to literature, films, visual art or music, it denotes a narrative of a possible future for Africans, Africa or the black diaspora. Science fiction emerged out of the need to make sense of the new technologies developed after World War I, and Afrofuturism represents an attempt to utilise this genre to make space for Africans and the black diaspora (Yaszek 2006:46). Mark Dery coined the term "Afrofuturism" in his essay "Black to the future" (1993). Many critics expanded on the term until it encompassed a variety of different phenomena, making it difficult to define precisely.

Even if descriptions of Afrofuturism tend to differ, Afrofuturism always involves the imaginary construct of an alternative future for African-American and African people. It uses black experience to reclaim Africans' future, because they all share (post) colonial traumas, fragmented identities and stolen history. Chardine Taylor-Stone (2014:[sp]) emphasises that 'black science fiction can provide a new language to address the increasingly complicated frameworks of discrimination'; she adds that Afrofuturism adds a lot more 'to the black experience than simple escapism, silver Dashikis and pyramid-shaped spaceships'. In terms of the aesthetics of Afrofuturism, it does include 'silver Dashikis and pyramid-shaped spaceships', but also blends African traditions and oral literature with fantasy, time travel and advanced science.

Before the development of Afrofuturism, not many black science fiction protagonists existed. Black readers initially had to identify with white heroes, which, according to Adilifu Nama (2008:134), caused internalised feelings of racial inferiority. It has been just over forty years since black superheroes made their entrance in science fiction comic books (Nama 2008:135). These characters are important because they offer "alternative possibilities" and provide 'a more complex and unique expression of black racial identity' (Nama 2008:136),

They are SF signifiers that attack essentialist notions of racial subjectivity, draw attention to racial inequality and racial diversity, and contain a considerable amount of commentary about the broader cultural politics of race in America and the world.

Afrofuturism has evolved into more than an aesthetic. It stands for a political mission, an emancipatory program.

Comic books and ideology

For a long time, comic books were neglected in literary criticism. This changed in the twentieth century as comic book criticism developed as an academic discipline. In their article Justice framed: law in comics and graphic novels (2012), Luis Gómez Romero and Ian Dahlman (2012:7) sum up the qualities of comics, which constitute their so-called "four-fold symbolic handicap" in comparison to "high literature",

First, comics are "a hybrid", the result of crossbreeding between text and image'; Second, comics' 'storytelling ambitions seem to remain on the level of a 'subliterature'; Third, comics are connected to a 'common and inferior branch of visual art, that of caricature'; and fourth, comics propose 'nothing other than a return to childhood', even when they are intended for adults.

Along with these four handicaps, they highlight another one. Comics were long the scapegoat for projecting "moral and socio-political accusations" on. It was said that reading comics would corrupt the reader. However, contemporary literary criticism has shown that a 'comic's aesthetic conventions can complicate its political, ethical and legal narrative' (Romero & Dahlman 2012:11). This is because 'words can be visually inflected when aesthetically rendered and juxtaposed with pictures, while pictures can become as abstract and symbolic as word' (Romero & Dahlman 2012:11). Matthew P McAllister, Edward H Sewell and Ian Gordon (2001:3) bring this complex relationship between image and text to bear on understanding the relationship between comic books and ideology. According to them, the combination of words and pictures has flexibility in terms of the manipulation of meaning. Comic books, as polysemic texts, lend themselves to different and multiple interpretations.

Randy Duncan and Matthey J Smith (2009:247) point out that, 'Ideologies aren't hidden ... as they are composed of taken for granted assumptions about the way the social world is supposed to work'. They emphasise that ideology is intertwined with issues of power, 'Those who benefit from a dominant idea often wield power in a society' (Duncan & Smith 2009:248). Art is often used as a tool to spread a dominant way of thinking, 'Propaganda tries to reach a large audience through the use of mass media and attempts to create a uniformity of interpretation among audience members by using what are arguably manipulative techniques' (Duncan & Smith 2009:248). This was also the case in the early production of comics.

Duncan and Smith (2009:251) discuss the comic books produced during World War II and the Vietnam War as illustration. In these comics, protagonists were easily divided into the heroic 'good guys', mostly the Americans, and the 'bad guys', the enemies of America. This overly simplified distinction meant that the bad guys were always represented as ugly and stupid. The stress lay on the heroic deeds of the Americans and these comics seldom highlighted the impact of war on the country where it is fought and its inhabitants (Duncan & Smith 2009:251). In response, anti-war comics were created. They focus on the horrors of war and question the influence of ideology on war comics, 'In this way, they may oppose the dominant ideology of their times' (Duncan & Smith 2009:252).

Panel containing the first reference to Black Panther in Fantastic Four #52 (1961), written by Stan Lee and art by Jack Kirby (reprinted in Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:113) ©MARVEL (fair use copyright permission).

These theoretical approaches highlight how comics tend to engage with current socio-political problems: sometimes reflecting (deliberately or not), the ideology of the time, and sometimes explicitly challenging it. Even mainstream comics such as those produced by 'The Big Two' publishing companies, Marvel and DC, often do not simply unconsciously reflect dominant ideologies, but also critically explore real world philosophical and political issues. In the rest of this article, we argue that this is also the case in Coates's version of Black Panther.

Black Panther and ideology

The first appearance of King T'Challa was in 1961, in Fantastic Four #52.

The outdated and stereotypical ideas from that era is represented in the Thing's description of Black Panther as 'some refugee from a Tarzan movie', who could not be expected to possess sophisticated technology. In 1998, Christopher Priest took over the Black Panther narrative and in 2005, Reginald Hudlin continued the adventures of the Panther until 2016, when Ta-Nehisi Coates took over.

In interviews, Coates gives an indication of what he wanted to achieve with his variant of Black Panther. He knows his predecessors and how they portrayed Black Panther,

Priest had the responsibility to get people to take this guy seriously ... Then I feel like the next thing Hudlin was trying to do was almost like trying to write this character for black folks. It was like not only is he badass but you know he is going to tell these white folks what time it is. [laughs]. (Coates, quoted in Narcisse 2016b:[sp]).

Coates does not completely retool Black Panther, but rather picks up the story where his predecessors left it. It is therefore necessary to provide a brief history of Wakanda and the Black Panther, before discussing ANUOF specifically.

Wakanda is one of the first fictional African countries whose prosperity and richness is not obtained owing to western influences like colonisation. Instead, it owes its economic welfare and stability primarily to the presence of the fictional element 'vibranium' (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:4). Vibranium can absorb sound waves, vibrations and kinetic energy and is therefore a sustainable, but also dangerous, natural resource which can be found abundantly in Mena Ngai, 'The Great Mound' (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:83). Because T'Chaka, the father of T'Challa, regularly sold vibranium, he could invest that money in the education of the Wakandans and in architecture and science. Therefore, Wakanda is one of the most technologically and socially advanced countries in the world (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:4).

In the Marvel universe, superheroes are generally normal humans who use technology to create a vigilante identity (for example Iron Man) or humans who, due to genetic mutations (the X-Men) or exposure to some body altering force (Spiderman), possess superhuman abilities. In contrast, Black Panther is conceived as an 'ancestral ceremonial title', blessed by the goddess Bast, passed along from generation to generation through the royal ancestral line (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:4). Black Panther's abilities are enhanced through his/her suit, which can be altered by the use of vibranium.

In an interview with Coates, Evan Narcisse (2016b:[sp]) says that Coates is 'destroying everything [that] every black nerd loves about Wakanda. It's not this perfect gleaming Pan-African paradise anymore.' He refers to Coates's concept of the Mecca and says that Wakanda is not the Mecca. Coates does not respond to this part of Narcisse's question, only acknowledging that he is not idealising Wakanda, because he is building on the history of the fictional country as written by Priest and Hudlin. He is imagining what state a country with so much collective trauma would be in (Narcisse 2016b:[sp]). As we have already argued, the ideological conflict in Coates's Wakanda does make it the Mecca, as it reflects the ideological conflict present in real world spaces that Coates considers "Meccas".

ANUOF begins with Wakanda fractured by earlier attempts to infiltrate or dominate the country and efforts to plunder Mena Ngai's vibranium. The last invasion killed T'Challa's sister Shuri, who temporarily took up the crown and the responsibility in Wakanda as Black Panther, while T'Challa was on an international mission (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:4). At the start of ANUOF people are revolting against the king, who they resent for neglecting them while forming part of the American superhero team, the Avengers. Meanwhile, some members of the all-female royal guard, the Dora Milaje, are also plotting against T'Challa, for not paying heed to the needs of women and children.

T'Challa, king and defender

The conflict within Wakanda is represented on the cover of ANUOF: Book One. T'Challa flexes his muscles, either in anger or in readying himself to fight. On both sides, he is flanked by flagpoles topped by Wakandan flags, in flames. These burning flags synecdochally represent the way Wakanda as a whole is simmering with tension.

T'Challa has various antagonists who are discussed in the rest of the article. He also has allies: Ramonda, his stepmother and a member of the Taifa Ngao, the 'shield of the nation'. Members of the Taifo Ngao who also play prominent roles in the narrative are the advisor Hodari and the soldier Akili. The name 'Shield of the Nation' is possibly a reference to uMkhonto weSizwe ('Spear of the Nation'), the militarised wing of the African National Congress in South Africa, with the word 'shield' emphasising defence rather than the offence implied by 'spear'.

The way in which T'Challa is represented in ANUOF illustrates the difficult task every ruler has: they should be a ruler of and a servant to the people. This theme might be universal, but in ANUOF it is explored specifically within the context of African autocracies. Darryl Holliday (2016:[sp]) summarises ANUOF's central concern as being the question, 'Can a good man be a king, and would an advanced society tolerate a monarch?'. The character of Zenzi pinpoints T'Challa's struggle with this issue by saying that he 'does not want to be a king. He wants to be a hero' (Coates et al. 2016a:24). This struggle makes T'Challa a typical superhero from the Silver Age, as described by José Alaniz (2014:19): he is characterised by a 'meta-narratival introspective mode', 'a greater psychological depth' and an 'admixture of irony, tragedy, and alienation [because his] powers separate[s him] from society'.

The only conflict in ANUOF that plays out in simple binary 'villains versus heroes' terms, more typical of the Golden Age of comics (Gravett 2005:74), involve American characters that become embroiled in Wakandan conflict. These villains are Zeke Stane, a black market weapons dealer, and his associates, the racist Fenris Twins (Coates et al. 2016a:53). While they are obvious 'bad guys', the other opposing forces represented in ANUOF are too complex to simply be deemed villains. Correspondingly, Black Panther's own motivations are not represented as purely heroic. It would be more accurate to describe him as a protagonist with various antagonists.

T'Challa does not act as the reader would expect of a hero, when he consults with 'counterrevolutionary' leaders who suppress their own people (Coates et al. 2016a:13). He does not listen to their advice and comes to regret the consultation (Coates et al. 2016a:24). When Tetu ensures that this consultation becomes public knowledge, it negatively affects the way Wakandans view T'Challa (Coates et al. 2016a:25-26). These other autocratic rulers claim that T'Challa is no different from them, that they all share the tradition of 'holding a nation under our feet' (Coates 2016a:14). T'Challa does not agree, 'I am a king ... And while they derive their power from gun barrels, I derive mine from a god' (Coates et al. 2016a:15). We return to the divine power of a king, and the responsibilities this involves, later in the article, when discussing Shuri. First T'Challa's various opponents and their motivations are analysed.

Zenzi and populism

The narrative of ANUOF starts at Mena Ngai. Throughout, T'Challa's interior monologue is communicated in black caption boxes with white text. As the caption boxes in Figure 3 indicate, T'Challa went to Mena Ngai to praise the miners, but they are filled with hatred. The miners' glowing green eyes in the second panel visually suggest that their actions are supernaturally provoked. This suspicion is proved correct when it is revealed on page 17 that the miners have been influenced by the powers of Zenzi.

Zenzi has the superpower of bringing others' suppressed feelings to the fore (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:20 & 46). Her influence on the miners might therefore seem to invalidate their actions. However, Zenzi says that she did not cause the miners' actions, but rather 'revealed to them, in all their agony, their deeper selves' (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:20). She sees herself not as "an exhorter", but as a liberator. That her power not only lies in surfacing suppressed thoughts, but also emotions, is indicated by the fact that she especially values rage and hope. These are the emotions she believes can be mobilised to political ends (Coates et al. 2016b:18-19).

The rhetorical employment of rage and hope play a prominent role in what Belgian philosopher Chantal Mouffe (2018:37) calls the contemporary 'populist moment'. Mouffe argues that while populism is most commonly associated with right wing politics, it should rather be conceived of not in terms of contents, but as a political form. In this respect, she follows Ernest Laclau who defines populism as 'a discursive strategy of constructing a political frontier dividing society into two camps and calling for the mobilization of the "underdog" against "those in power"'. It is not an ideology and cannot be attributed a specific programmatic content' (Mouffe 2018:94). In a similar way, Zenzi seemingly does not have an agenda, but rather has the ability to mobilise any people around their frustrations and especially their resentment of those who have more power. Tetu, on the other hand does have an agenda, and it is he who manipulates her abilities.

Tetu's violent defence of his ecological spirituality

Tetu used to be a student, but he left the university to join the Shaman. When prodded by his former teacher, the philosopher Changamire, for his reasons for doing this, he says that he considers both science and mysticism as the search for knowledge (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:43). Changamire correctly notes that Tetu's actions are not only driven by the search for knowledge. Tetu acknowledges his political aims, claiming that he has 'founded an order that fights to protect Wakandans while our king slaughters them' and that he did this for the sake of a better country (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:43).

The reader is provided with an indication of the nature of Tetu's mysticism and his political beliefs at the start of Black Panther (2016) (See Figure 4).

His thoughts, presented in grey caption boxes, communicate a panpsychist worldview. In keeping with a monist form of panpsychism, he conceives of his own consciousness as being part of a mentality fundamental to and ubiquitous in the natural world (see Goff, Seager & Allen-Hermanson 2017). In the dust clouds doubling as Tetu's thought bubbles, the course of history is depicted, with people appearing on earth and initially having a spiritual deference to the mentality of nature - worshipping at the roots of divinity.

Eventually, however, industrialisation takes place, visually represented by cityscapes. Humans do not defer to 'spirits' any more (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:55). While Tetu's motivations may be intellectually, spiritually, and ecologically viable, he resorts to violence to make 'flesh' listen. He utilises Zenzi's powers to manipulate Wakandans, orchestrating the violent protests at Mena Ngai and the detonation of a bomb in Birnin Zana (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:92-93). Zenzi's influence is necessary to motivate the bomber, since it is a suicide bomb, implanted in his body (Coates et al. 2016a:11).

Tetu's fight is not only for his own ideology, but also against the actions of T'Challa and monarchy in general (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:68-69). He claims that he is fighting for the sake of Wakanda, but he later admits that he believes that the only way to destroy T'Challa's rule is to destroy Wakanda itself (Coates et al. 2016a:69). His use of suicide bombers were therefore foreshadowing and functions as synecdoche for his overarching strategy.

The Midnight Angels' radical feminism

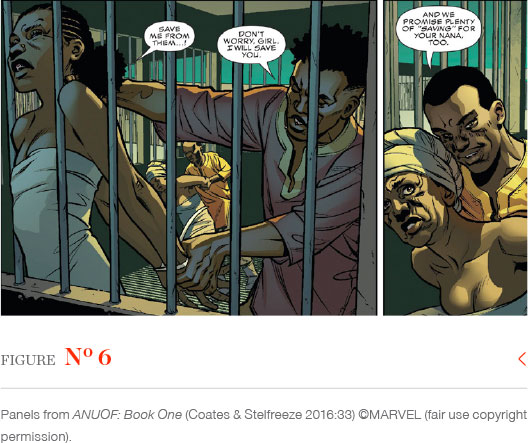

The Midnight Angels (although not yet named thus) are introduced near the beginning of ANUOF: Book One. Ramonda, T'Challa's stepmother, sentences Aneka, a member of the Dora Milaje, to death (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:15). Aneka murdered a chieftain as revenge for the 'outrages [he enacted] upon the girls of his village' (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:14). Shortly after receiving her death sentence, Aneka manages to escape from her cell with the help of Ayo, her 'beloved', who is also a member of the Dora Milaje (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:23).

Aneka and Ayo go on to form the Midnight Angels, who also oppose T'Challa's rule. Whereas Zenzi and Tetu's antagonism towards T'Challa is not represented as unmotivated, the reader might be expected to be more empathetic towards the Midnight Angels, given how they are first introduced through the representation of Aneka's unjust sentencing.2

The reader is again implicitly invited to root for the Midnight Angels when they are depicted as the saviours of a young girl and her grandmother, M'bali, who are captured by warlords and threatened by rapists. After fighting them off, a Midnight Angel declares, 'Wakanda has not yet died!' (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:35). This implies that although they are fugitives from the state, they are still fighting for the nation of Wakanda.

This is clarified further in Aneka's words to the girl, that she deserved a 'Wakanda that cherished you'. Ayo replies that while Wakanda still does not value the lives of girls and women, the Midnight Angels will avenge them. The words 'No one man', in the bottom panel of Figure 7, presumably refers to Wakanda's totalitarian monarchism, with the country being ruled by only one man - an aspect that Ayo had already criticised earlier, stating, 'No one man should have that much power' (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:28). The gendered nature of this statement is also relevant, given that the Midnight Angels are an all-female group of vigilantes, avenging the crimes of men.

While they use violence to protect women and children, the Midnight Angels also attempt to utilise democratic methods, 'assembling communes, calling for elections, writing and enforcing laws' (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:78).

The peacefulness of the scene depicted in Figure 8, in the depiction of a community established by the Midnight Angels, can be contrasted with the dark prison that the women were rescued from, in Figure 6.

The feminism central to the Midnight Angels' revolution is acknowledged in a speech by Aneka, attempting to rouse her troops to fight the soldiers sent to contain them, 'Once we were bred by men solely to give our bodies to other men ... We have seen how the woman becomes the enslaved ... Let us now show them how the enslaved becomes a legend' (Coates et al. 2016a:30-31). Unprompted, Zenzi uses her powers to help the Midnight Angels defeat the soldiers. This leads to an alliance between the Midnight Angels and Tetu and Zenzi's group ('The People') (Coates et al. 2016a:35).

The Midnight Angels learn, however, that in the wake of The People's actions the same kinds of rape and abuses follow as those that they avenge (Coates et al. 2016b:13). In working in solidarity with The People, the Midnight Angels' feminist ideals are compromised. While Tetu acknowledges that rape and abuse is wrong, his attitude is still patriarchal, as exemplified by his speech in a video call, in Figure 9. The silhouette of M'bali, with her head in her hands, conveys her frustration with Tetu's inability to understand their complaints.

After the call ends, the Midnight Angels discuss this dilemma. While Aneka says that they have no choice but to work with The People as they have no other army, Ayo says that this sounds like the excuses of a 'warmongering barbarian out of the west' (Coates et al. 2016b:15). The scene ends with M'bali echoing (African-American feminist) Audrey Lorde's famous quote, 'The master's tool will never dismantle the master's house' (Lorde 1983:94), implying that the Midnight Angels cannot use the methods of patriarchal tyranny to fight patriarchal tyranny.

Changamire's pacifist liberal critique of monarchy

Changamire is a 'dissident philosopher' and a teacher at Hekima Shulé in Birnin Azaria, a Wakandan city (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:42 & 75). Hodari explains that Changamire was handpicked as a tutor for T'Chaka's court, and would therefore have been T'Challa's teacher, except that he was exiled from the court for his anti-monarchist views.

The reader first encounters Changamire in Black Panther (2016) #2, standing in front of a classroom and quoting from John Locke's The second treatise of civil government (1690),

The injury and the crime is equal, whether committed by the wearer of a crown or some petty villain ... Great robbers punish the little ones to keep them in their obedience, but the great ones are rewarded with laurels and triumphs . because they are too big for the weak hands of justice in this world, and have the power in their possession, which should punish offenders ... What is my remedy against the robber, who so broke into my house? (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:42).

In The first treatise of civil government, Locke refutes the Divine Right of Kings doctrine of Sir Robert Filme (Uzgalis 2018). Filme contends that kings are descendants of the first man, Adam, and all other people are rightfully their slaves. Locke counters that this claim cannot be supported by reason or reference to scripture (Uzgalis 2018). In the second treatise, Locke is still implicitly refuting Filme's argument, but he is now providing a positive version of how government should come into being, rather than just criticising the monarchy. Locke bases his theory of government on the then-popular concept of the social contract (Uzgalis 2018). According to Locke, people agree that their condition in the state of nature is unsatisfactory and therefore confer some of their rights to the central government, while retaining others (Uzgalis 2018). Legitimate government can only be instituted by the explicit consent of those governed and becomes illegitimate when non-consensually intruding on their rights (Uzgalis 2018).

Changamire is presumably attempting to compel his students to reflect on T'Challa's recent actions, including the suppression of the protesters at Mena Ngai. After the students leave the classroom, Tetu enters. He attempts to persuade Changamire to support his movement (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:43). Changamire initially refuses to get involved, claiming a Socratic distance ('The questions are the point'), which leads Tetu to accuse him of being 'shut up in thought and abstraction' (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:43; emphasis in original).

Changamire's pacifism is also criticised by Ramonda. She says that Changamire never understood that 'the first rule of any government was to safeguard the people' and that this sometimes means resorting to violence (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:86). However, she also acknowledges that Changamire understood something that T'Chaka never did, namely that 'protection is not enough. Force is not enough' (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:87). Rather, deliberation is necessary to determine what values are worth protecting.

Changamire is only spurred into action when he sees the video that Tetu distributes seemingly showing the autocratic leader of a fictional Eastern European country, explaining that he advised T'Challa to spread 'ordered chaos' (Coates et al. 2016a:23). Tetu edited the video to not include the admission that T'Challa refused to take his advice. It is this video that motivates Changamire to lead peaceful protests (Coates et al. 2016a:28).

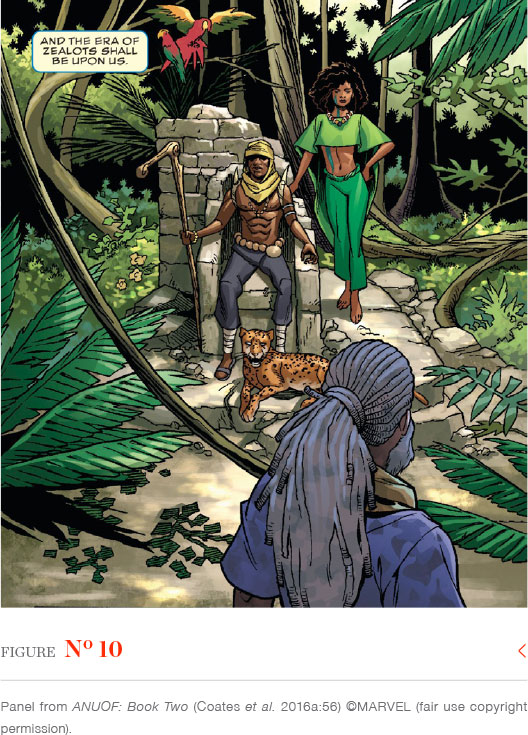

Hodari claims that while Changamire invokes the pacifism of Ghandi, his followers understand, 'the violence of his message ... The heretic proposes to end the rule of the panther and elevate anarchy in its place'. T'Challa refuses to be swept up by Hodari's rhetoric and acknowledges Changamire's actual stance in favour of democracy and against monarchy (Coates et al. 2016a:28-29; emphasis in original). Even after committing to action, Changamire is still a pacifist, and he still fears the violence that the conflict might engender, thinking, 'Now I am old, and I fear that some young dreamer shall resolve [the dream of a democratic revolutions but the rejection of violence], and commit to that which is both terrible and plain ... And the era of zealots shall be upon us' (Coates et al. 2016a:55). The reader's suspicion that Tetu is the 'young dreamer' and 'zealot' he is referring to, is confirmed by the juxtaposition of his words with the image of Tetu in Figure 10.

The juxtaposition of the words with the image is reminiscent of McAllister et al.'s (2001:1) claims (mentioned earlier) that the relationship between text and image in comic books has the potential to complicate ideological readings. In Figure 10, Tetu looks powerful and Zenzi seductive, but Changamire's description of Tetu as a 'zealot' allows for the image to seem ominous, rather than desirable.

Like the Midnight Angels, Changamire regrets helping Tetu's cause by organising protests in reaction to the released video, which he knows is a misrepresentation of T'Challa's views and actions (Coates et al. 2016a:69). While he supports Tetu's rejection of autocratic monarchism, he (again, like the Midnight Angels) believes Tetu's methods are as tyrannous as theirs. Through the study of history, he knows that the implementers of laudable ideals are often corrupted when they try to implement them, 'It's the history of man. Washington to Napoleon to Mobutu. Liberators turned slave-holders and then all again' (Coates et al. 2016b:7).

Shuri's monarchism, rooted in ancestry and myth, and her influence on T'Challa

Black Panther (2016) #1 ends with T'Challa going to the burial site of the previous Black Panthers (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:27). It is revealed that he is trying to resuscitate his sister, Shuri. Shuri is not dead, but not alive either (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:50). She is still conscious on some level, in the Djalia: Plane of Wakandan Memory. In this plane she is guided by a figure who takes the form of Ramonda, but isn't her (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:61). This figure is a griot, a caretaker of Wakanda's histories (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:62).

Echoing Tetu's rejection of industrialisation, the griot tells Shuri that while she has always been told that Wakanda's power lies in its 'wonderful inventions, in its circuits and weaponry' the secrets of its greatness is actually much older than vibranium (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:61). Shuri replies that vibranium 'guided us through our savage years', to which the griot responds 'Do I seem savage to you?' (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:61). This response can be seen as a rejection of the idea that Africa as a continent is more barbaric and undeveloped than the global North. Whereas Afrofuturism generally shares this rejection, it usually (as in other versions of Black Panther) does this by associating technological advancement with Africa. This association is complicated in ANUOF, through an acknowledgment of the ecological destruction and the devaluation of spirituality and tradition that most often accompanies technological advancement.

The griot says that Shuri, and those who ruled before her, have lost their way, but that the griots will arm her, 'not with the spear, but with the drum' (Coates & Stelfreeze 2016:63). The allusion here is to the value of African oral literary traditions. As can be seen in Figure 11, Shuri and the Griot are surrounded by semi-translucent figures, representing their ancestors. In the first panel, these figures are beating on drums, visually symbolising the 'power of song'. If the realm in which Shuri finds herself is the same one that Tetu has a connection with, the reaction elicited in her (to empower through memory and art) is much different than Tetu's violent response. The griot 'arms' Shuri by telling her tales of Wakanda's history, and about all the different cultural groups who live in the Wakandan region. After telling her two stories, Shuri starts telling her stories, indicating that she does not need the griot's guidance anymore, but is herself now a griot. The first and last stories deal with leaders who realise that they can defeat their enemies if they become one with their people, instead of ruling over them.

This is the end of Shuri's journey in the Djalia - after telling the last story, she is transported back to Wakanda, with the help of Manifold.

Back in Wakanda, Shuri looks different (compare Figure 13, portraying Shuri after her return from the Djalia, to Figure 12, Shuri before the Djalia). She now has grey hair and is wearing the armour of the ancestral griots pictured in Figure 11. Her words indicate that in the Djalia, Shuri did not learn new things, but rather that everything needed to resolve the conflicts in Wakanda was already present in 'Wakanda's collective knowledge' (Coates et al. 2016b:3), its history and lore. This collective knowledge is what should be used to find solutions to Wakanda's problems, rather than violence and technology. T'Challa and Shuri utilise Wakanda's history quite literally, when, with the help of Manifold, they open the gate between the living and the dead and the dead help them to fight The People (Coates et al. 2016b:47-49).

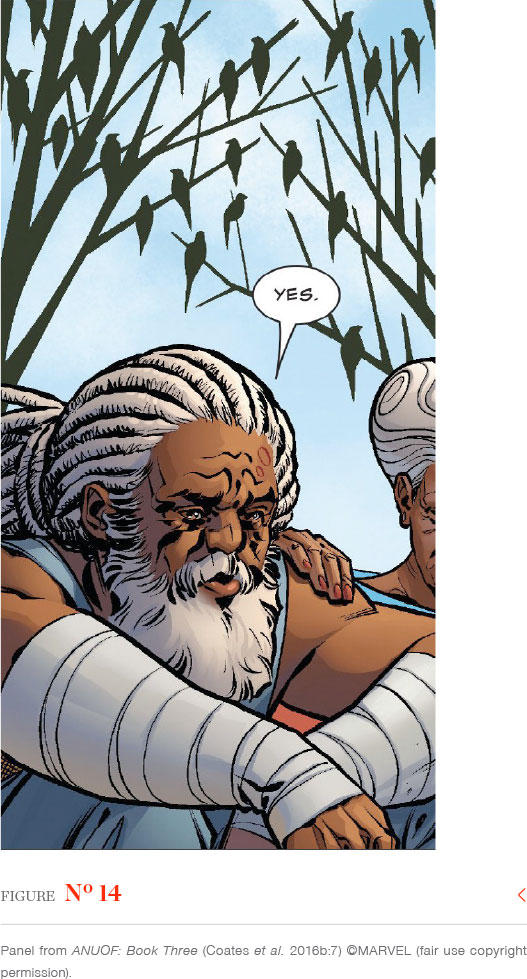

Shuri's insight that knowledge and narratives are important is also represented by her new superpower - the ability to travel in the form of a swarm of birds (Coates et al. 2016b:7). This links with her newfound perspective on Wakanda, as it enables her to observe people and listen to their stories. The reader first learns this he/she sees a conversation between Changamire and Khadijah, his wife.

Initially, the reader presumes that this is the perspective of an omniscient focaliser, as in the rest of ANUOF, but it becomes clear that this is the point of view of Shuri as the birds visible in the background of Figure 14. She is able to relay the conversation to T'Challa, who now knows enough to conclude that Changamire is 'a good man' (Coates et al. 2016b:5). He realises that while Changamire brandishes 'an impractical morality', as king he himself preaches 'an immoral practicality' (Coates et al. 2016b:8). A balance between the two is needed, and in the rest of ANUOF he attempts to attain this balance by working with Changamire. He convinces Changamire to use the trust his moral integrity has inspired in the Wakandans to convince them not to believe Tetu (Coates et al. 2016b:39 & 54).

Shuri also goes to the Midnight Angels to listen to Aneka. She, however, empathises less with them, possibly because the Dora Milaje used to be her guard and she feels betrayed by them (Coates et al. 2016b:29). She says that while she can understand their vengeance against the abusive chieftains, she resents the way they have indebted themselves to Tetu (Coates et al. 2016b:30). She warns them that if they do not honour their pledge to protect the king, she will destroy them (Coates et al. 2016b:31). After she leaves, the Midnight Angels again discuss their options. M'bali is in favour of supporting Shuri. She says that, through the actions of themselves and Changamire, Wakanda has changed such that T'Challa cannot turn on the Midnight Angels if they support him. This is in contrast to Tetu, who they expect will betray them. Because most Wakandans now support Changamire and the Midnight Angels, T'Challa would once again war against his own people if he wars against the Midnight Angels (Coates et al. 2016b:33).

T'Challa has in the meantime learned, through Shuri's influence, that he cannot consider himself separate from Wakanda (Coates et al. 2016b:41) and therefore he would not commit violence against his own people. As Changamire says when trying to persuade Wakandans to support T'Challa, 'No one man can possess all the wisdom. No one man can have all the power' (Coates et al. 2016b:57). He echoes the Midnight Angels' creed, but here he is not arguing that T'Challa should be opposed, rather that, if T'Challa supposes himself a member of his people and not raised above them, they should support him and together improve his leadership. This does not mean that he should be followed no matter what, but it does mean that the leadership style advocated by Shuri and Changamire at the end of ANUOF is of a leader who does not separate himself from and attempts to discipline his people, but rather works with them.

ANUOF ends with T'Challa vowing to create, with the input of all Wakandans, 'a new constitution, and ultimately a new government, elected by Wakandans ... The creed shall be - no one man'. As king he will represent the people, but not rule over them (Coates et al. 2016b:89; emphasis in original).

Conclusion

In ANUOF Wakanda functions as a metaphorical Mecca, a fictional space in which ideological conflicts pertaining specifically to Africans and African Americans are explored. In its centralisation of these conflicts, it disrupts, in an Afrofuturist way, the white hegemony within science fiction. While the ideological issues represented by the different characters in ANUOF, namely autocratic monarchism, populism, religiously motivated violence, ecological awareness, feminism, pacifist liberalism and attempts at reconceptualising monarchism and tradition, have specific implications for Africa, they also relate to global political trends and conflicts. In this way, ANUOF is typically Afrofuturist in that it looks to Africa for answers for the future, rather than seeing Africa as an underdeveloped continent and relic of the past.

Further research could be done on whether the solutions to global conflict posited in ANUOF ignores the problems of democracy and western nationalism. By representing Wakanda as an (ancient) nation, even though it consists of eclectic cultural groups, the concept of a nation state is reified and the specific circumstances that lead to the creation of African nations are ignored. This is, however, outside of the scope of this article.

Notes

1 . ANUOF: Book One collects Black Panther 2016 #1-4. Coates is credited as the writer, Stelfreeze as the artist and Martin as the colour artist of all four issues. ANUOF: Book Two collects Black Panther 2016 #5-8. Coates is again credited as the writer and Martin as the colour artists of all four issues, with Story credited with inks/finishes and Sprouse with pencils/layouts. ANUOF: Book Three collects Black Panther 2016 #9-12. Coates is the writer and Martin the colour artist of all four issues, but the credits of the other issues differ. Stelfreeze is credited as the artists of issues #9 and #12. Sprouse is credited with the layout of issues #10 and #11 and (along with Stelfreeze) with the pencilling of issue #12.

2 . Aneka and Ayo would indeed go on to be the protagonists of Black Panther: World of Wakanda Vol. 1 - Dawn of the Midnight Angels (Coates, Gay, Harvey & Brown 2016).

Acknowledgements

Bibi Burger wishes to thank the American Council of Learned Societies' African Humanities Program for financial support.

REFERENCES

Alaniz, J. 2014. Death, disability and the superhero: the silver age and beyond. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. [ Links ]

Anderson, R & Jones, CE (eds). 2016 [2015]. Afrofuturism 2.0: The rise of astro-blackness. Lanham: Lexington Books. [ Links ]

Bucciferro, C. 2016. The X-Men films: a cultural analysis. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [ Links ]

Coates, T. 2008. The Beautiful Struggle: A Father, Two Sons, and an Unlikely Road to Manhood. New York: Spiegel & Rau. [ Links ]

Coates, T, Gay, R, Harvey, Y & Brown, R. 2016. Black Panther: World of Wakanda Vol. 1 - Dawn of the Midnight Angels. New York: Marvel. [ Links ]

Coates, T & Stelfreeze, B. 2016. A nation under our feet book one. New York: Marvel. [ Links ]

Coates, T, Sprouse, C, Story, K & Martin, L. 2016a. A nation under our feet book two. New York: Marvel. [ Links ]

Coates, T, Stelfreeze, B, Sprouse, C & Martin, L. 2016b. A nation under our feet book three. New York: Marvel. [ Links ]

Coates, T. 2017. We were eight years in power: an American tragedy. New York: One World. [ Links ]

Dery, M. 1994 [1993]. Black to the future, in Flame wars: The discourse of cyberculture, edited by M Dery. Durham & London: Duke University Press:179-222. [ Links ]

Dery, M (ed). 1994. Flame wars: the discourse of cyberculture. Durham & London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Duncan, R & Smith, MJ. 2009. The power of comics: history, form and culture. New York: Continuum:246-267. [ Links ]

Goff, P, Seager, W & Allen-Hermanson, S. 2017. Panpsychism. Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. [O]. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/panpsychism/ Accessed: 14 September 2018. [ Links ]

Gordon, I. 1998. Comic strips and consumer culture, 1890-1994. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press:59-79. [ Links ]

Gravett, P. 2005. Graphic novels: stories to change your life. London: Aurum. [ Links ]

Holliday, D. 2016. Ta-Nehisi Coates' new comic book 'Black Panther #1' is 'black as hell. In these times. [O]. Available: http://inthesetimes.com/article/19016/black-panther-ta-nehi-coates-review. Accessed: 22 September 2018. [ Links ]

Locke, J. 1999 [1690]. The second treatise of civil government. [O]. Available: https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/politics/locke/index.htm. Accessed: 13 September 2018. [ Links ]

Lorde, A. 1983. The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house, in This bridge called my back: Writings by radical women of color, edited by C Moraga & G Anzaldúa. New York: Kitchen Table Press:94-101. [ Links ]

McAllister, M, Sewell, EH Jr & Gordon, I (eds). 2001. Introducing comics and ideology, in Comics and ideology, edited by M McAllister, EH Sewell Jr & I Gordon. New York: Peter Lang:1-13. [ Links ]

McAllister, M, Sewell, EH Jr & Gordon, I (eds). 2001. Comics and ideology. New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Moraga, C & Anzaldúa, G (eds). 1983. This bridge called my back: writings by radical women of color. New York: Kitchen Table Press. [ Links ]

Mouffe, C. 2018. For a left populism. London: Verso. E-book. [ Links ]

Nama, A. 2009. Brave black worlds: Black superheroes as science fiction ciphers. African Identities 7(2):133-144. [ Links ]

Narcisse, E. 2016a. Ta-Nehisi Coates explains how he's turning Black Panther into a superhero again. Kotaku 15 September 2016. [O]. Available: https://www.kotaku.com.au/2016/09/ta-nehisi-coates-explains-how-hes-turning-black-panther-into-a-superhero-again/. Accessed: 22 June 2018. [ Links ]

Narcisse, E. 2016b. Spoiler space: More from Ta-Nehisi Coates on Black Panther. Kotaku 4 June 2016. [O]. Available: https://kotaku.com/spoiler-space-more-from-ta-nehisi-coates-on-black-pant-1769472432. Accessed: 22 June 2018. [ Links ]

Romero, LG & I Dahlman. 2012. Justice framed: law in comics and graphic novels. Law Text Culture 16(1):3-32. [ Links ]

Taylor-Stone, C. 2014. Afrofuturism: where space, pyramids and politics collide. The Guardian 7 January 2014. [O]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/science/political-science/2014/jan/07/afrofuturism-where-space-pyramids-and-politics-collide. Accessed: 8 August 2018. [ Links ]

Uzgalis, W. 2018. John Locke. Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy. [O]. Available: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/locke/#TwoTreaGove. Accessed: 13 September 2018. [ Links ]

Yazsek, L. 2006. Afrofuturism, science fiction, and the history of the future. Sociology and Democracy 20(3):41-60. [ Links ]

Zacarias, M. 2016. Radical plots in comic books? Communist Party of Australia 6 April 2016. [O]. Available: http://www.cpa.org.au/guardian/2016/1725/15-radical-plots.html. Accessed: 22 June 2018. [ Links ]