Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.37 Pretoria 2023

https://doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a1

ARTICLES

"Speak to a community audience": The Staffrider illustrations of Mzwakhe (Muziwakhe Nhlabatsi) 1979-1987

Deirdre Pretorius

Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture, Graphic Design Department, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. dpretorius@uj.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3174-5403)

ABSTRACT

The South African literary and arts magazine Staffrider (1978-1993) is known for its Black Consciousness stance and the contribution it made in the struggle against apartheid. From its inception the magazine contained illustrations, photographs, artwork and graphics alongside prose, poetry, plays, essays and reports, and for nearly a decade illustrations signed by 'Mzwakhe' appeared frequently. Mzwakhe, the pen-name of Muziwakhe Nhlabatsi, contributed a sizeable number of illustrations to accompany the writing of several notable South African authors. This article offers a discussion of his illustrative contribution to Staffrider in the period from 1979 to 1987 in the context of Black Consciousness as a counter to hegemonic apartheid discourse. I discuss Black Consciousness and the 'Black Consciousness Aesthetic' (Hill 2018) in relation to his illustrations, point out the reciprocal relationship between his educational work for the South African Committee for Higher Education (SACHED) and his cartoons and comics for Staffrider and describe his portraits and the influence of African masks on his work. Staffrider presented the opportunity for a counter discourse to the official apartheid narratives to be published (Manase 2005:70) and I argue that Nhlabatsi contributed to this counter discourse through his illustrations which visualised Black Consciousness in a variety of styles and techniques and the humanity, beauty and dignity with which he rendered most of his subjects.

Keywords: Muziwakhe Nhlabatsi, Mzwakhe, Mtutuzeli Matshoba, Staffrider, Black Consciousness, SACHED, apartheid, comics, counter discourse.

Introduction

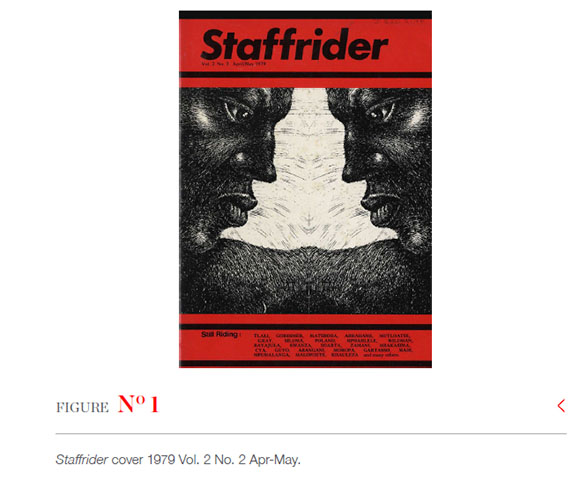

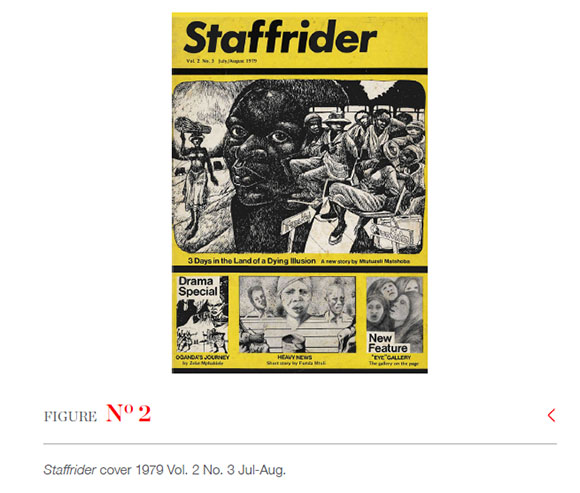

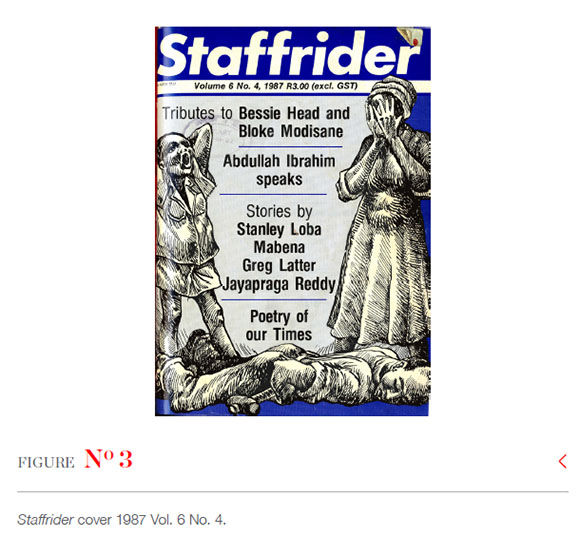

The contribution made by the South African literary and arts magazine Staffrider (1978-1993) (Figures 1, 2 and 3) in the struggle against apartheid is acknowledged by Michael Vaughan (1985:219), Irikidzayi Manase (2005:56), Keyan Tomaselli (2019:339), Mark Espin (2021:24) and Katie Reid (2021:282). The journal was the 'literary focal point of the Black Consciousness generation' (Penfold 2015:1) and printed prose, poetry, plays, essays and reports, some of which were accompanied by illustrations, as well as documentary photographs, artwork and graphics.

Vaughan (1985:219) describes Staffrider literature as being 'committed to an ideological assault upon the racism of the apartheid State'. Staffrider was concerned with providing a space for the voices of the people living in townships to be heard, thereby showing how individuals experienced oppression and contributing to 'consciousness-raising' - a central concern of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) (Vaughan 1985:196,208). Vaughan (1985:197-198) names this approach 'populist polemicism' and considers it a form of political and ideological struggle against apartheid.

Manase (2005:70) affirms that Staffrider offered an important platform for the distribution of 'information and imaginings that reflected the experiences of the oppressed and excluded'. In this way the magazine presented the opportunity for a counter discourse to the official apartheid narratives to be published, thereby making 'oppressed urban readers ... aware of their censored past and other social and historical conditions that affected them'. The magazine has received some scholarly attention,1 however, the illustrations signed by 'Mzwakhe' have largely been overlooked,2 despite his contribution being described as 'notable' in the preface to the tenth anniversary edition of the magazine (Oliphant & Vladislavic 1988:x).

Mzwakhe was the pen-name of Muziwakhe Nhlabatsi3 whose first illustrations in Staffrider appeared in the second number of the second volume in 1979, and his last in the fourth number of the sixth volume of 1987. His work appeared on three of the magazine's covers (Figures 1, 2 and 3) and over 70 of his images were printed in the magazine to illustrate short stories, extracts from books, poems, plays and other texts by notable South African authors; including Es'kia Mphahlele, Ahmed Essop, Njabulo Ndebele, Mothobi Mutloatse, Mtutuzeli Matshoba, Chris van Wyk, Mongane Wally Serote and Andries Oliphant.

Nhlabatsi was born on 20 April 1954 and has lived and worked for most of his life in Soweto and Johannesburg. He received his early art training from two Johannesburg based art centres; the Jubilee Art Centre under Bill Hart (1969-1972) and the Mofolo Art Centre under Daniel (Dan) Sefudi Rakgoathe (1970-1971) (Nhlabatsi 2018). From 1976 to 1977 he attended the Evangelical Lutheran Church Art and Craft Centre established at Rorke's Drift (ASAI 2020), an institution which is acknowledged as having played a key role in the development of black artists, and especially of printmaking, in South Africa (Hobbs & Rankin 2003:6). With very few exceptions, art training for Black artists in South Africa until the mid-1980s was confined to such art centres which operated outside of the formal education sector and played an important role 'in the culture of resistance' (Rankin 2011:53). As at other art centres, black-and-white relief printmaking was an important area of focus at Rorke's Drift (Hobbs & Rankin 1997:15), but during Nhlabatsi's years he was also exposed to graphic design and screen printing through the efforts of then newly appointed lecturers Jules and Ada van der Vijver, who aimed to prepare students for the 'urban job market in an increasingly industrialised South Africa' (Hobbs & Rankin 2003:131).

During the seventies Nhlabatsi worked as an artist and art teacher, had a solo exhibition and participated in five group exhibitions in South Africa and two international group exhibitions (ASAI 2020). From the late 1970s Nhlabatsi moved away from the visual arts and teaching prompted by his preference for graphics and the need to generate an income, and started practicing as a 'graphic artist', as he prefers to refer to himself (Nhlabatsi 2020b).

During the eighties he worked as a graphic artist for the South African Committee for Higher Education (SACHED) and Maskew Miller Longman and co-founded the production studio The Graphic Equalizer with Kevin Humphrey and Andy Mason (Mason 2014). The Graphic Equalizer was responsible for the layout and reproduction of Staffrider from 1981 to 1986, with Nhlabatsi being credited by name in 1985 for this task. Nhlabatsi's output during the eighties included educational materials for SACHED, and illustrations for several publishers, including Skotaville Publishers, Maskew Miller Longman and Ravan Press, the publishers of Staffrider (Nhlabatsi 2018).

The one author whose work he illustrated most frequently for Staffrider was Mtutuzeli Matshoba, a Black Consciousness writer (Vaughan 1981:45-47, Gaylard 2008:218) and prolific contributor to Staffrider during the early years of its existence. I (Pretorius 2021) have examined these illustrations for the Africa South Art Initiative (ASAI) website and aim here to extend my analysis from a focus on Nhlabatsi's illustrations for Matshoba's writing, to his entire illustrative contribution to Staffrider in the period from 1979 to 1987. The discussion of his work is done in the context of Black Consciousness and proceeds by briefly discussing Black Consciousness and 'The Black Consciousness Aesthetic', as outlined by Hill (2018), in relation to a selection of the Matshoba illustrations. Thereafter I point out the reciprocal relationship between his educational work for the South African Committee for Higher Education (SACHED) and his cartoons and comics for Staffrider and I conclude with a description of his portraits for the magazine and the influence of African masks on his work.

The Black Consciousness aesthetic

The BCM, which is closely associated with student activist Steve Biko, emerged in the mid-1960s and aimed at political liberation, and reclaiming African identity and blackness (Johnson & Jacobs 2011:36). The BCM considered all people categorised under apartheid as African, Indian and Coloured as being black (Johnson & Jacobs 2011:36). The movement realised the value of culture in communicating and expressing Black Consciousness ideals and encouraged and influenced artistic expression profoundly (Hill 2015:4,12). Artists aligned to the BCM aimed their work at black audiences and used black culture as a source of imagery and inspiration (Vaughan 1984:196).

Judy Seidman (2011:105) and Andy Mason (2010:105) have commented on the influence of Black Consciousness on Nhlabatsi with Mason asserting that his illustrations 'effortlessly exuded the ethos of Black Consciousness'. Nhlabatsi's consciousness was shaped by reading 'furiously' and by discussing and exchanging books with others, including titles by banned writers and 'a lot' of Biko's work (Nhlabatsi 2020b). From the 1970s his approach to art aligns with what Seidman (2007:49) identifies as the broad principles of Black Consciousness in the arts, namely self-expression, creating work reflecting your own and your community's experiences and interests, using the styles and artistic vocabulary of your community and defining the audience for your message.

An article for Staffrider written on visual arts by Nhlabatsi (1979:54-55) evidences his alignment to Black Consciousness. Here he argued for contact between the artist and the black public and the need to exhibit in communities and to give expression to lived experience. He criticised the structural inequalities in South Africa, emphasised the need for art education and writing on art and 'safe-guarding our heritage, culture and art' Nhlabatsi (1979:55).

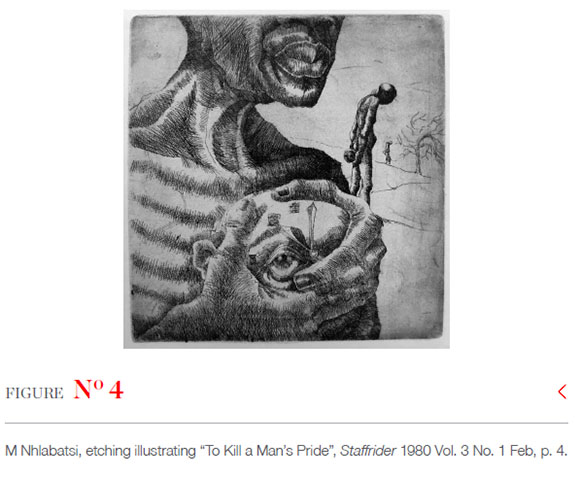

The etching (Figure 4) illustrating an extract from Matshoba's short story "To Kill a Man's Pride" in Staffrider, a reprint of a student work created at Rorke's Drift, is interpreted by Philippa Hobbs and Elizabeth Rankin (2003:197) as having 'a surrealist quality reminiscent of the works of Fikile'. Nhlabatsi (2020b) acknowledged the influence of Salvador Dali on this particular image and he knew Fikile Magadlela and his work, having exhibited alongside him in the 1974 Group of Six and the 1975 Tribute to Courage exhibitions (Nhlabatsi 2018).

The work of Fikile Magadlela (1954-2003) is singled out by Shannen Hill (2015:1819) as the epitome of 1970s Black Consciousness art. Hill (2018:201) argues that a 'Black Consciousness aesthetic' developed during the early 1970s in the work of black artists working between Johannesburg and Pretoria and in addition to Magadlela, identifies Thami Mnyele, Motlhabane Mashiangwako and Lefifi Tladi's work as being exemplary of this style. Characteristic of their work was the representation of human figures in transitory states and as blending with their backgrounds, which prompted comparison of their work to Surrealism (Hill 2018:198).

Hill (2015:18) disagrees with the view held of early Black Consciousness artists as 'African surrealists', arguing that 'these artists actually visualised Black Consciousness-they re-presented it for our contemplation'. For Hill (2015:xviii) the cultural components of Black Consciousness in South Africa revolved around 'the pride, beauty, strength, and humanity of black cultures'. Like Nhlabatsi, Mnyele and Magadlela's work was also printed in Staffrider, but far less frequently.

During the 1970s Nhlabatsi often interacted with Mnyele, Magadlela and Matsemela Manaka and while being appreciative of their 'arty' work, his focus was on illustration as he believed that Black people cannot afford art, the only way to reach them is through graphics, publications ... I could reach a larger audience - speak to a community audience' (Seidman 2007:95). He therefore moved into working as a graphic artist during the late 1970s and developed a recognisable illustration style for Matshoba's Black Consciousness writing.

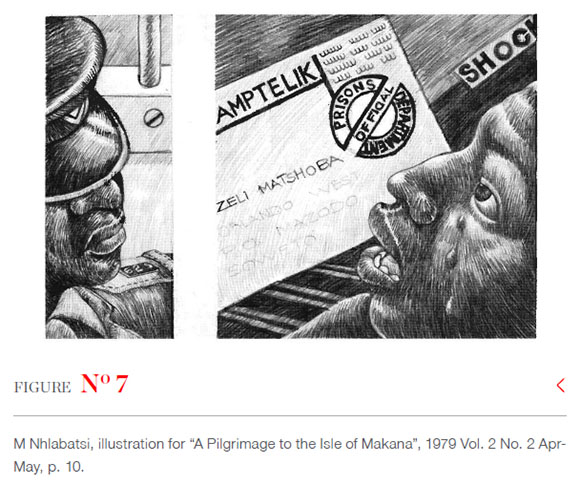

Typical of this style is his cover illustration for Matshoba's book Call me not a man (1979) (Figure 5) which is executed in a densely hatched, solid and powerful style in which the human figure is drawn with humanity, beauty and dignity. These characteristics are present in most of the illustrations created for Matshoba's writing, for example "Towards Limbo" (Figure 6) and "A Pilgrimage to the Isle of Makana" (Figure 7). These illustrations for Matshoba's writing are not merely literal reflections of the text, but imaginative constructions drawing on the story as a starting point and informed by discussions with the author and provides evidence of the freedom Nhlabatsi enjoyed in creating illustrations for Staffrider (Pretorius 2021).

The office of Ravan Press in Johannesburg was a meeting place for writers, poets, photographers, illustrators and artists and here Nhlabatsi participated in book discussions, exchanged ideas, and developed friendships. His friendships with writers helped him to gain insight into their work which, in turn, helped him create appropriate illustrations to accompany their texts, and he remained lifelong friends with Matshoba (Nhlabatsi 2020a).

His creative process commenced with reading the text, then formulating ideas, after which he would create a drawing 'out of my head' or from reference material which he would obtain from the Johannesburg Public Library, because the libraries in Soweto were not adequate (Nhlabatsi 2020b). This illustration would be presented to the commissioning editors for approval and publication (Pretorius 2021).

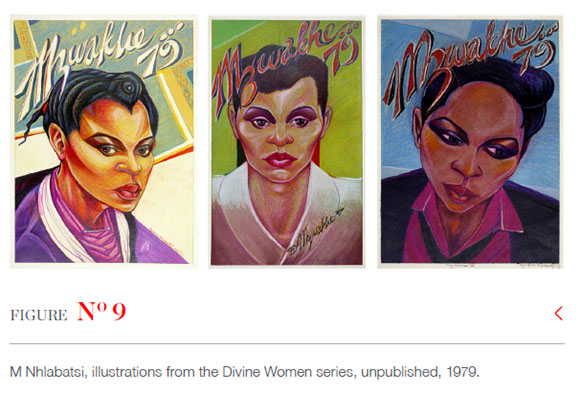

Nhlabatsi's portraits of Matshoba's protagonists are beautiful, a visual expression of the Black Consciousness slogan 'Black Is Beautiful' (Hill 2015:4) and Magadlela's view that 'if you draw a black man, he must be beautiful, handsome; the woman must be heavenly' (Magadlela cited by Hill 2015:18). This is true of the majority of Nhlabatsi's subjects, with the exception being his caricatures which serve to ridicule subjects through exaggerated features and gestures. Nhlabatsi's intention to convey beauty becomes evident in the fact that his cover for Call me not a man shows a striking resemblance to a fashionable and glamorous portrait of a woman (Figure 8), which formed part of a series of unpublished portraits of women created during 1979 under the title 'Divine Women'.

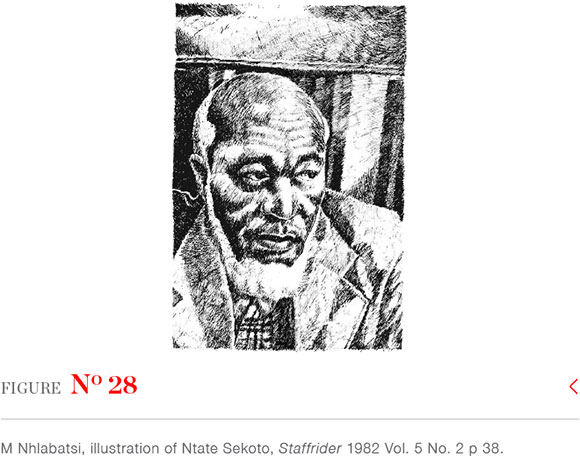

The Divine Women series (Figure 9) expresses Nhlabatsi's interest in fashion, he 'liked fashion' and bought fashion magazines to study the layouts. His interest in fashion saw him studying at Archie Leggat's fashion academy in 1980 through which he entered, and won, a fashion design competition run by the French private airline, Union de Transports Aériens (UTA). His prize allowed him to travel to Paris where he took the opportunity to seek out South African artist Gerard Sekoto who had been living there since 1947 (Nhlabatsi 2020b). Sekoto was considered a 'pioneer of modern African art' (Figlan 1982:38) and Nhlabatsi 'adored' him and was drawn particularly to Sekoto's early work (Seidman 2007:96).

In addition to illustrating for Staffrider, he was appointed at SACHED from 1979 to 1981, filling a position vacated by Mnyele, and again from 1986 to 1993, to create educational graphics. John Aitchison (2003:133) considers SACHED to be the most prominent and impactful educational Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) to function in South Africa. The organisation promoted alternative education, which was deliberately in opposition to the apartheid state-run education, by offering support to University of South Africa (UNISA) students, providing secondary education through correspondence, and delivering high quality course materials (Aitchison 2003:133). At SACHED Nhlabatsi had the opportunity to develop his comic and cartooning skills, and this development was reflected in his work for Staffrider.

Cartoons and comics

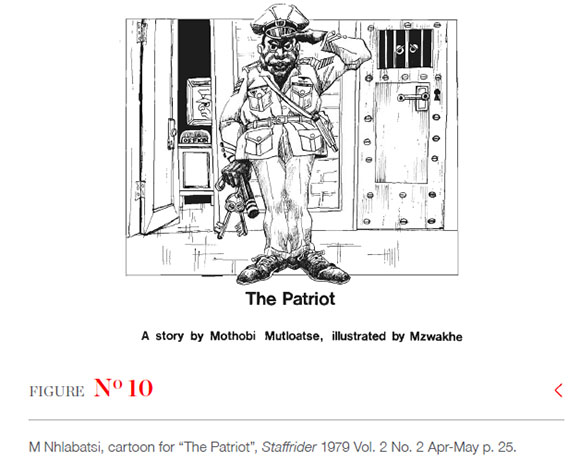

The cartoon in Figure 10 illustrates the satirical story "The Patriot" by Mothobi Mutloatse and appears in the same issue as Matshoba's story "A Pilgrimage to the Isle of Makana". The images are strikingly different, showing Nhlabatsi's proficiency in moving between styles appropriate to the tone of the writing he was illustrating. "The Patriot" is a satirical tale that relates the story of a man, who, on being inspired by an article on fighting for your country against the communists, resigns as a teacher and becomes a soldier fighting on the border, thereby evoking the anger of his family. Upon returning home after six months of service, he is robbed and arrested for not carrying a pass.4 As his family expected, the same system for which he fought proves to have turned on him. The story is illustrated by way of exaggerated, humorous caricatures to reflect the satirical tone. A satirical tone is also present in the story "The Rebel Leader" by Michael Siluma, which appeared in the same issue and is similarly illustrated (Figure 11). With regard to these cartoons, Nhlabatsi (2020b) explained that at the time he was reading the newspaper, The Sowetan, which did not print cartoons, so he developed a character that he hoped the newspaper would adopt. When this plan did not realise, he used the character for Staffrider instead.

Such caricatures by Nhlabatsi did not appear frequently in Staffrider. What is more prevalent, are the other drawing styles which he developed for SACHED. At SACHED he created illustrations for educational publications, such as the monthly Upbeat magazine for school children, which provided him with the opportunity to create comic strip work (Mason 2010:105). According to Mason (2004:154) SACHED's Upbeat and People's College Comics tended to be characterised by the 'cross-hatched black and white "underground" comix style'. Educational comics, also known as 'non-fiction cartooning', containing information and political analysis, emerged out of the United States' underground comics scene, and became a trend by the late 1970s (Brown 1990:426-427). Brown (1990:426-431) identifies the influence of the educational comics trend in South Africa in SACHED's use of comics in their educational publications and refers to the work of Mason and Dick Cloete, Rick Andrews and Nhlabatsi in this regard. SACHED's stated purpose with developing comics was to 'introduce readers to good novels and to popularise history' (SACHED 1990:9).

Nhlabatsi had no formal training as a cartoonist and this skill was not part of the curriculum at Rorke's Drift and hence he developed his cartooning skills 'along the way'.5 He met Andy Mason, a self-confessed underground comix 'addict' (Mason 2010:86), who worked at Ravan Press from 1979 to 1980 as a trainee editor and production coordinator (Mason 2021), and who was developing his own comic drawing skills.6 Mason (2010:85) explains that the 'scribbly, untidy' underground comix appealed to him far more than the 'slick, professionally produced comics' of his youth. They discussed and exchanged resources and techniques on creating comics and worked together at The Graphic Equalizer (Nhlabatsi 2020b). According to Nhlabatsi 'Andy was a bit messy and I would show him put your arm up do this do that and he'd be happy with that and then say, "oh this is how you keep your work clean"' (Nhlabatsi 2020b). Mason (2004:253), in turn, described Nhlabatsi as 'a highly skilled illustrator with a distinctive style'.

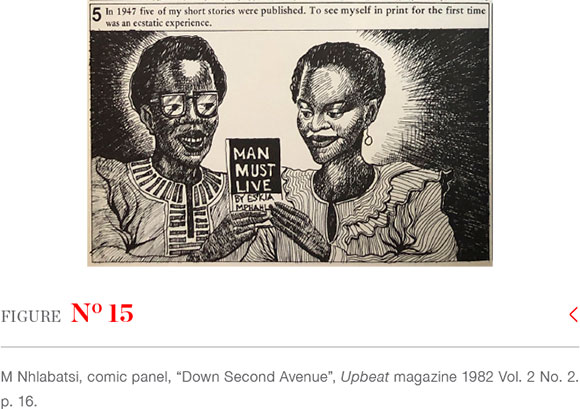

During 1981 Nhlabatsi created a serialised monthly comic strip for Upbeat, titled "Down Second Avenue" (Figure 12), based on the autobiography of Es'kia Mphahlele, first published in 1959. Nhlabatsi would also create comics for NgügT wa Thiong'o's "Weep Not Child" and "Romance at Riverside High" by Chris van Wyk, which were also serialised in Upbeat (Mason 2010:105-106). Seidman (2007:95) states that Nhlabatsi aimed to use comics to 'consciously build African culture, making Mphahlele's writing available to children and less literate people'. Seidman (2007:60) quotes Nhlabatsi as saying that 'SACHED was just a job, but whatever we were doing was for the people'. According to Nhlabatsi (2020b) cartoons were used to motivate children to read, with the hope that if a child read a comic, they would later read a book. The "Down Second Avenue" strip was published as a compilation in 1988 as the first title in SACHED's People's College Comics series (Mason 2010:105). It is interesting to note that while this comic has been studied by John Trimbur (2009) and Mona Schauer Young (2010), these researchers do not refer to Nhlabatsi by name or discuss his imagery at all. This is a strange oversight, particularly considering that Trimbur (2009:88) believes that People's College Comics 'pose political and ethical questions for popular literacy projects about who is included in the popular classes and how people are represented, in the double sense of being figured as a political force and of being spoken on behalf of'.

In a review of "Down Second Avenue", Joshua Brown (1990:431) gives Nhlabatsi's drawing due consideration, describing his style as 'ranging from punchy, "cartoony" panels-character's expressions and gesticulations wildly exaggerated-to much more circumspect, illustration-like pictures'. He comments on Nhlabatsi's ability to successfully convey emotion and considers his drawing as displaying 'panache and wit' Joshua Brown (1990:431).

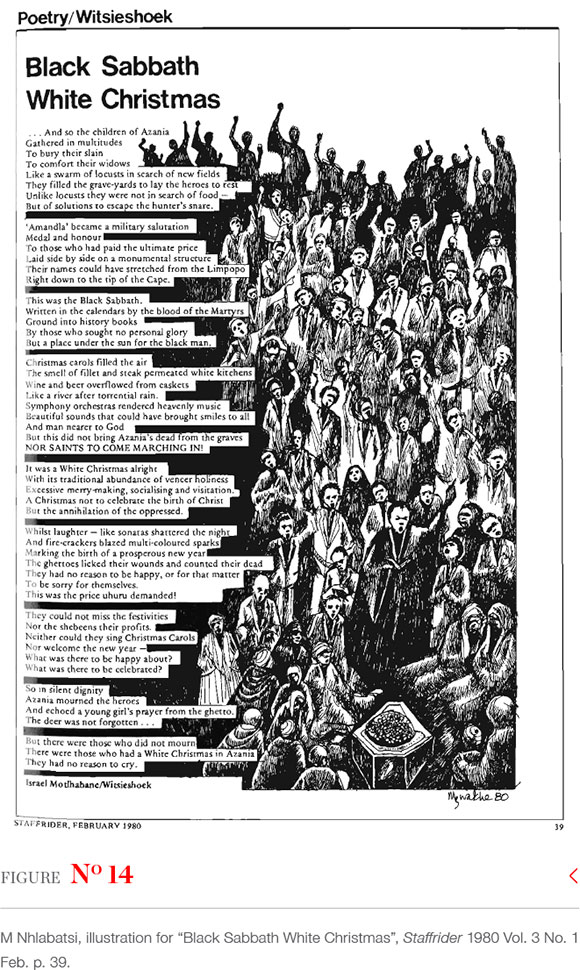

This diversity of styles used in "Down Second Avenue" is also visible in the pen and ink drawings that Nhlabatsi created for Staffrider. The loosely hatched, simplified drawing of the figures around the 'communal' campfire learning about 'history, tradition, communal responsibility and social living' in Figure 14 from "Down Second Avenue", is similar to the representation of the 'children of Azania gathered in multitudes' in the illustration for the poem "Black Sabbath White Christmas" in Staffrider (Figure 14). This deindividualised approach to drawing groups and crowds of people can be interpreted as an attempt to create an image of 'the people' to which Black South African literature had started to increasingly address itself (Vaughan 1985:200). The concept of 'the people' refers to all who were united in the struggle against apartheid (Vaughan 1985:201) and was an attempt to create a 'positive strategic identity' by Black Consciousness adherents who aimed at transforming the 'ghetto' 'into the community, the people' (Vaughan 1984:209, emphasis in original).

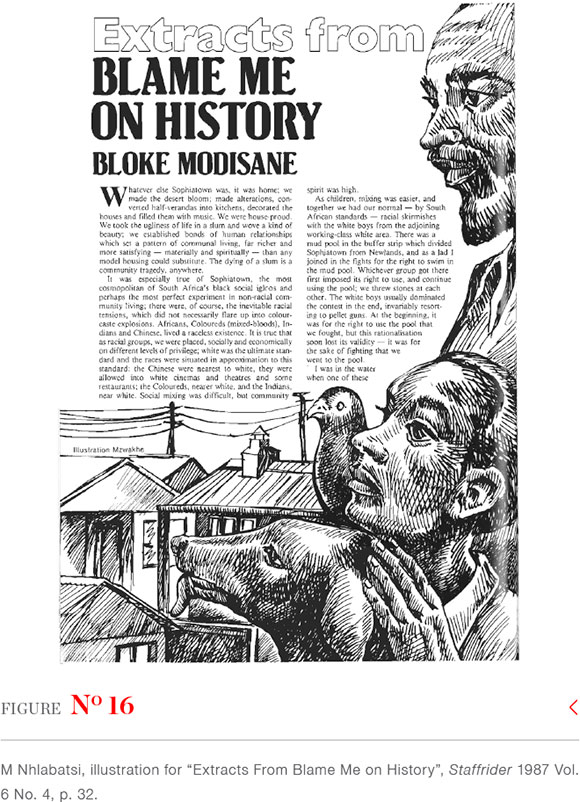

The loosely rendered style which depicts "the people", is in clear contrast to the more controlled line work and individualised features that characterise Nhlabatsi's illustrations of named persons. Figure 15 depicts Es'kia Mphahlele and Figure 16 a young Bloke Modisane in clearly delineated and empathetically rendered portraits accompanying their autobiographical writing. The contrasting styles used to depict the people versus the individual show what Vaughan (1985:213) has identified as the incomplete rejection of individualism in Staffrider, which stands in tension to Staffrider writers' criticism 'of the writer as an aesthete' and the collectivist endeavors of writer's groups in the townships.

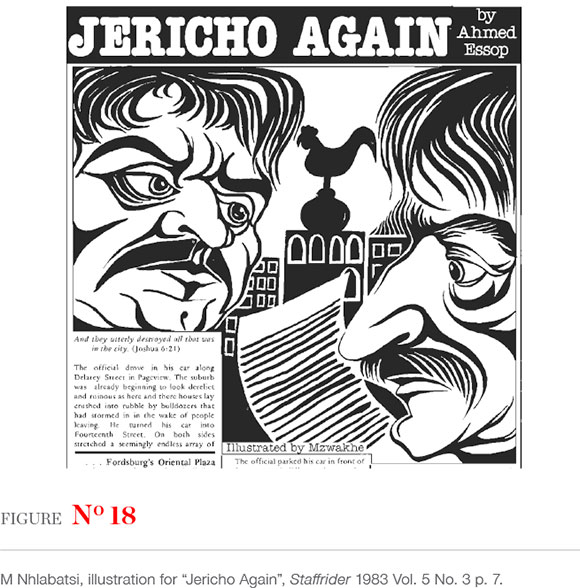

The attractiveness of these portraits, in turn, contrast with the exaggerated features of the caricatures in Figures 17 and 18. Figure 17 illustrates a short story conveying a banal telephone conversation between two white women, Chrissie and Pam, during which Pam harshly complains about a worker called John who dared to express his grief because of his mother's death in her presence. Figure 18 depicts a character named as 'the official', who, as an agent of the apartheid state, is instrumental in the protagonist Khalid and his wife Houda losing their home following the forced removal of people from Pageview. These caricatures embody the 'forces of oppression' through their 'malevolent human agency' and exemplify a 'sick humanity' (Vaughan 1985:213).

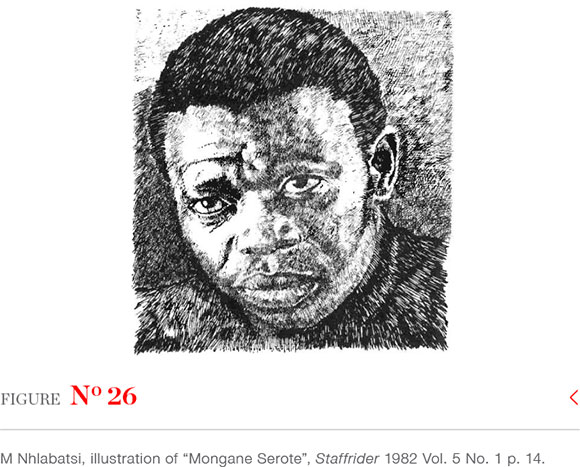

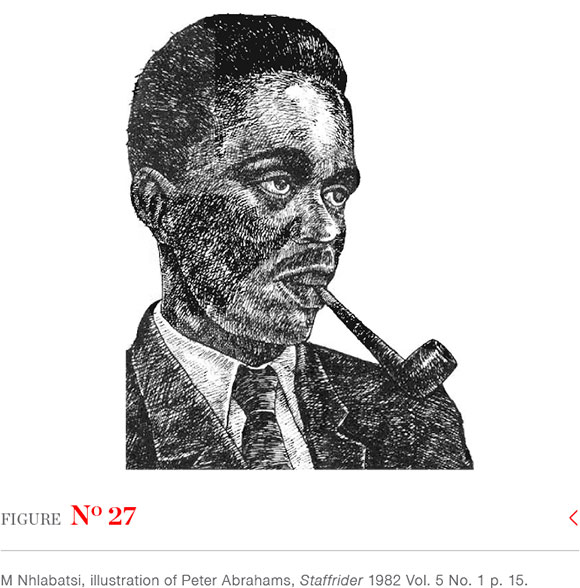

Vaughan (1985:219) identifies 'the preoccupation with individuals, either as "agents" of "the people" or of the apartheid state' as a prominent motif in Staffrider, and the portraits created by Nhlabatsi can be seen as a visual extension of this concern. The focus on the individual also aligns with Vaughan's (1985:212) observation of Black Consciousness's 'preoccupation with individual self-consciousness and its "liberation" through an affirmation of "Blackness"'.

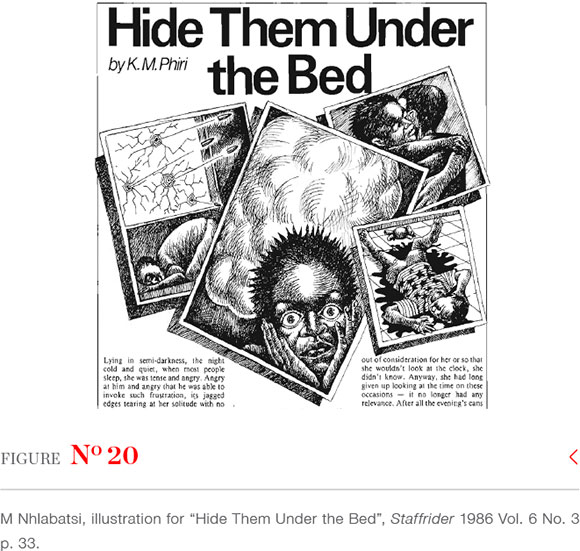

As Staffrider repeatedly drew on certain themes, Nhlabatsi also developed a repertoire of images that was repeatedly used across publications. This can be seen in panels from "Down Second Avenue" which show a boy cradling his head in his hands (Figure 19) and the depiction of a standing figure with hat and sunglasses (Figure 21) which reappear in Staffrider (Figures 20 and 22). This repetition might have been the result of the difficulty of obtaining reference material at the time, although, in the case of "Down Second Avenue", he was supplied with historical photographs of Marabastad to ensure accurate depiction, and he also used photographs by the Afrapix collective as reference (Nhlabatsi 2020b).

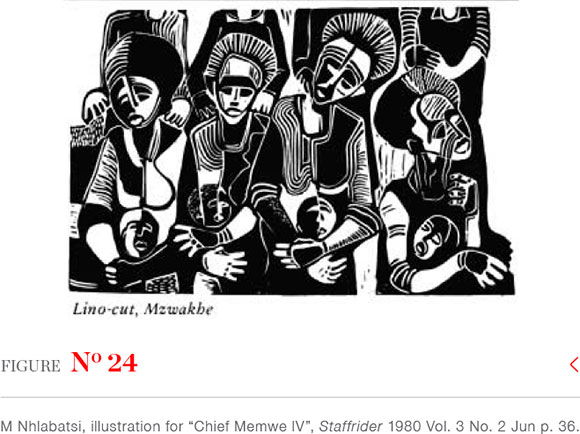

In addition to the pen and ink work, Nhlabatsi also contributed linocut images to Staffrider. These started appearing in 1980 and while some were reprints from his student days at Rorke's Drift, others were new creations.

Portraits and masks

A comparison of two images (Figures 23 and 24) printed in the second number of Staffrider of 1980 clearly shows the difference between the earlier work from Rorke's Drift, which was reprinted, and the newly created image. The first, a self-portrait by Nhlabatsi, in which he stares intently and unsmilingly at the viewer, illustrates a poetry section with contributions by Soweto poets. The linocut is credited to 'Mzwakhe/Soweto' and reflects self-respect and self-assertion, ideas promoted by Black Consciousness (Penfold 2015:2). The high contrast defining his facial features serves to create an impression of three dimensionality, whereas the high contrast used in Figure 24, a stylised group portrait of women mourning children, flattens out the image and emphasises the two-dimensional quality of the image. The use of such high contrast styles would only emerge again from 1983 to 1986, and then in an evolved form. In stark contrast to the self-portrait in Figure 23, Nhlabatsi created a series of finely hatched, sensitive portraits of South African authors and artists during 1982 as seen in Figures 25 to 29.

Figures 25, 26 and 27 illustrate an article outlining the development of black writing in South Africa from 1922 to 1982 (Rive 1982:12) and include a portrait of Mongane Serote, the 'poet laureate of the Black Consciousness generation' (Penfold 2015:2) (Figure 26) and the writers Richard Rive (Figure 25) and Peter Abrahams (Figure 27). Such articles were an attempt by Staffrider to 'recover and re-insert the writings of earlier generations' thereby 'restoring a suppressed tradition of resistance literature in South Africa' (Oliphant & Vladislavic 1988:ix). This restoration project was an ongoing concern for Staffrider and is demonstrated again in an article in the following issue on Gerard Sekoto, described as forming part of 'extensive research into modern African art' by Staffrider authors (Figlan 1982:38). Figures 28 and 29 show Nhlabatsi's finely observed portraits of Sekoto, an artist who he deeply respected, which illustrate the article.

This attempt at recovering the history of black South African artists and writers must be viewed in a context where such information was very scarce, suppressed or banned. For example, in 1979 when Nhlabatsi (1979:55) lamented the dearth of sources available on South African black artists, Staffrider was only able to identify one book, Contemporary African art in South Africa by AJ de Jager (1973), which it described as having useful illustrations but 'slightly patronising text', and three journals, African Art, Art Look and Lantern, which contained information on this topic. Nhlabatsi's portraits of South African artists and writers show reverence for his subjects, while emphasising their humanity, and contributed to the creation of a visual pantheon of role models for the younger generation.

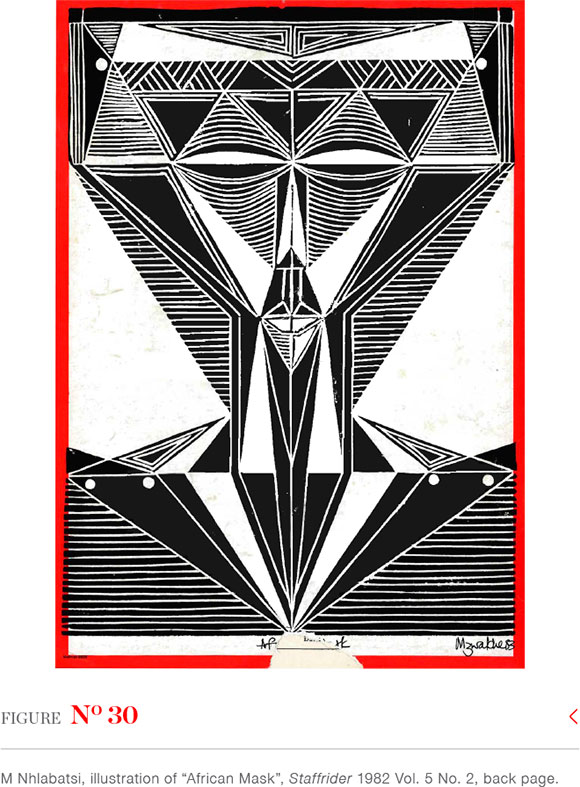

In Staffrider number 4 from 1980 a 'Staffrider Poster Series' was announced, created by Nkoana Moyaga of 'people's heroes - leading figures in black cultural and political life', the first of which were of Biko and Miriam Makeba. With these posters the magazine aimed to represent 'key elements of our history, our present, and our future' and Nhlabatsi's finely drawn portraits contributed to this project. However, this style was short-lived, and an image of an "African Mask" printed on the back page of the last Staffrider issue of 1982 (Figure 30) heralded the return of the strong, high contrast imagery which Nhlabatsi had last used in the magazine during 1980.

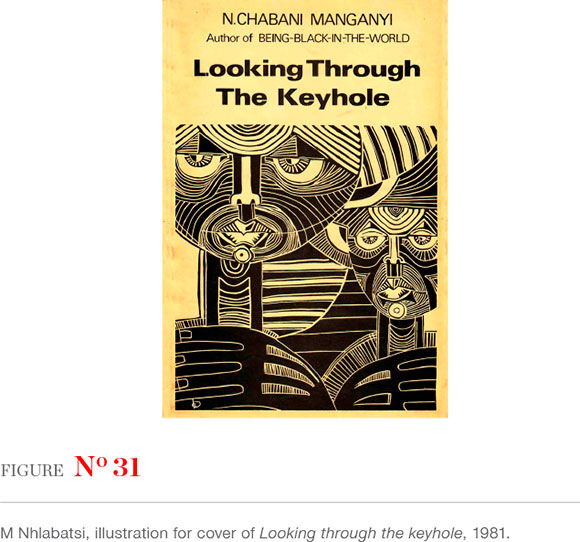

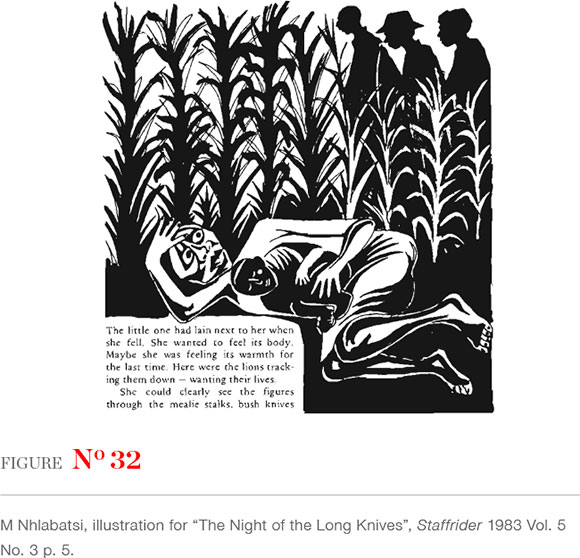

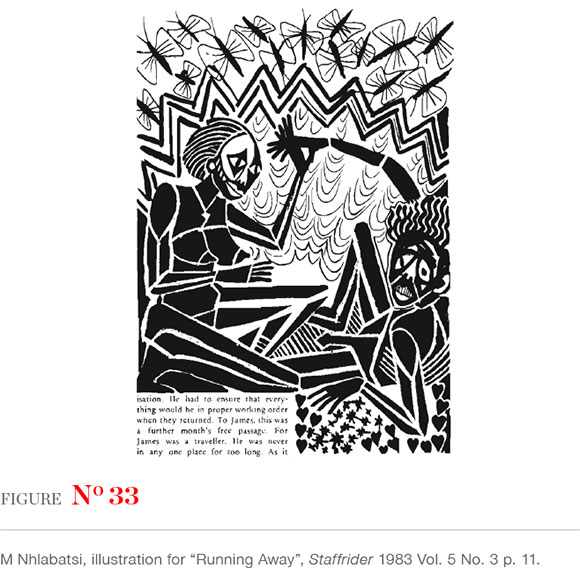

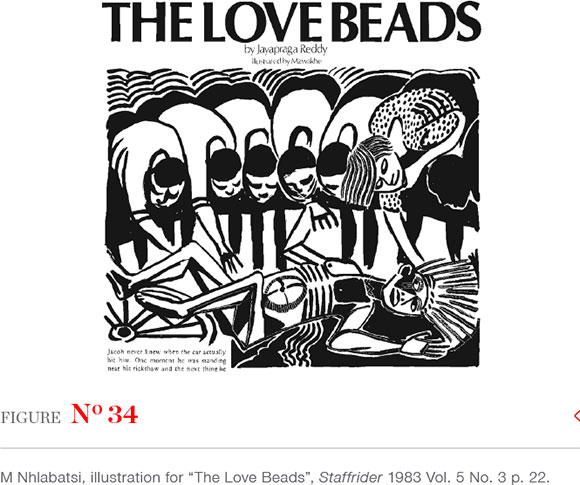

During 1983 Nhlabatsi created a series of increasingly abstract graphic illustrations (Figures 32, 33 and 34). These reflected his ongoing interest in using African masks as inspiration for developing his own style (Nhlabatsi 2020b). This influence is also visible in the book cover design for N Chabani Manganyi's book Looking through the keyhole (Figure 31) published by Ravan in 1981, where the symmetry and stylisation typical of African masks are applied in the depiction of the portraits.

Seidman (2011:109) notes that in an attempt to develop an 'aesthetics of struggle' cultural activists during the 1980s were 'researching, recovering and building upon Africa's cultural achievements' in a bid to counter the 'repression, denial, distortion and destruction of South Africans' knowledge of pre-colonial and black African cultures' by colonialism and apartheid. Nhlabatsi's use of masks, therefore, aligns with this drive to seek 'out Africa's artistic and aesthetic creations' (Seidman 2011:109).

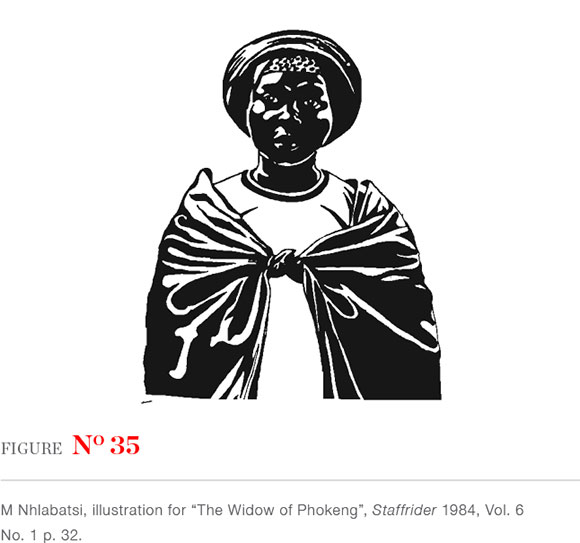

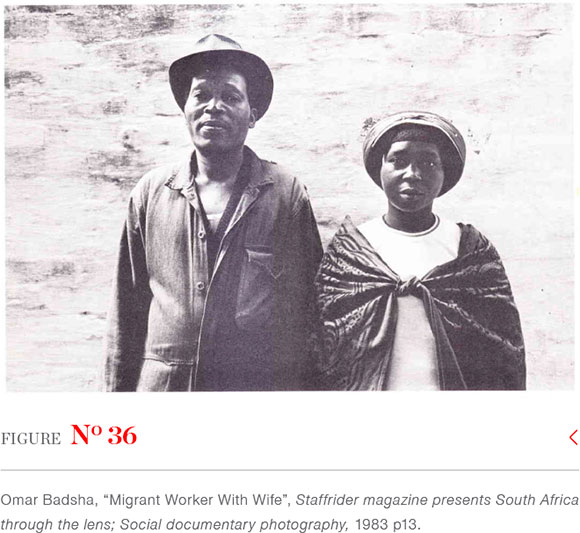

1984 saw Nhlabatsi returning to the high contrast style of portraiture, first seen in the linocut self-portrait from 1980 (Figure 23), with his portrait of a woman with a blanket tied across her chest (Figure 35). This image was copied from a photograph by Omar Badsha titled "Migrant Worker With Wife" (Figure 36). Badsha had been involved in the founding of the anti-apartheid photographers collective Afrapix, an organisation that aimed at documenting the struggle for freedom during the 1980s in South Africa (Badsha 2021). Badsha's photographs appeared regularly in Staffrider and his photo of the migrant worker and his wife graced the cover of, and was reprinted in, the Ravan publication Staffrider magazine presents South Africa through the lens: Social documentary photography (1983), a publication also designed by The Graphic Equalizer.

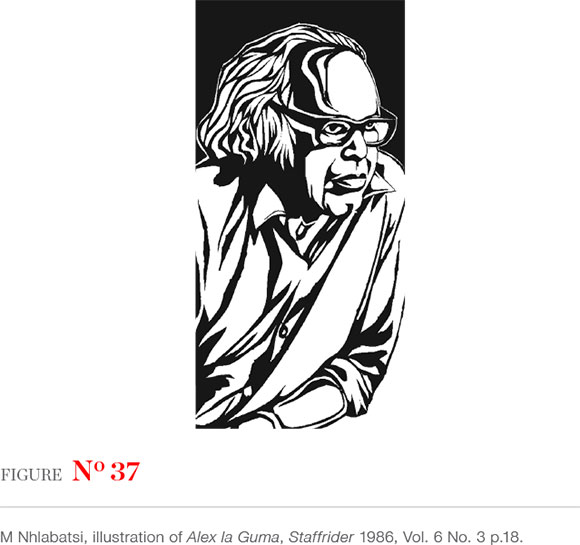

In 1986 Nhlabatsi used the same high contrast style to create a series of portraits of notable South African figures, including the writer Alex la Guma (Figure 37) and artist Thami Mnyele (Figure 38). The image of Mnyele was created in his memory after he had been killed by the apartheid government in Gaborone in 1985 (Wylie 2008). These portraits have an iconic quality and, while very different in style from the portrait series printed during 1982, can be viewed as a continuation of the canonisation of black authors and artists.

Conclusion

Manase (2005:70) argues that by reflecting 'the experiences of the oppressed and excluded', Staffrider provided a space for a counter discourse to apartheid narratives to be printed. This allowed urban dwellers to find 'new ways of seeing themselves and new ways of imagining their city and nation despite the existing pervasive apartheid domination' (Manase 2005:70).

Nhlabatsi's illustrations for Staffrider gave visual expression to this counter discourse by using a variety of styles and techniques to visualise Black Consciousness writing. This ranged from the heavily shaded, impactful graphic illustrations which he developed to illustrate the writing of Mtutuzeli Matshoba, to exaggerated caricatures, loosely drawn simplified figures and clearly outlined, detailed, individualised figures. His illustrations ranged from extremely stylised, high contrast graphics influenced by African masks, to delicate, carefully illustrated portraits of iconic South African writers and artists. A unifying element in most of these illustrations are the humanity, beauty and dignity with which he renders most of his subjects, all of which are aspects emphasised by Black Consciousness.

His contribution to Staffrider came to an abrupt halt with his last illustrations, and third cover, printed in 1987. It would appear that his retaking up of a position with SACHED in 1986 and his work at the Graphic Equalizer did not leave room for his continued contribution to Staffrider (Nhlabatsi 2018). Furthermore, in 1988 Staffrider had changed their designer and approach to the inclusion of graphics and visuals, and by 1989 no more illustrations appeared. Staffrider remained in print until 1993 when it finally ceased publication, a victim of the collapse of the alternative press resulting from external donor funding drying up in the transition to democracy (Mason 2004:395). Nhlabatsi continued working for SACHED until 1993 and has remained active as a graphic artist (Nhlabatsi 2018).

Acknowledgements

A draft of this paper was first presented at the online conference Disturbing Views: Visual Culture and Nationalism in the 20th and 21st Centuries hosted by the South African Research Chair in South African Art and Visual Culture, University of Johannesburg, 15-18 November 2021.

Notes

1 . See for example Vaughan (1984) on Staffrider and developments in South African literature during the 1980s and his reflections on the ideology of the magazine (Vaughan 1985), Maughan-Brown's (1989) critical review of the anthology Ten years of Staffrider (1989) and Mofokeng's (1989) questioning of the absence of female writers in their review of the same anthology. See also Chapman's (1999) exploration of whether Mtutuzeli Matshoba's stories that appeared in Staffrider contributed to defining African popular fiction, Ndebele's (1989) discussion of Staffrider in the context of the writer's movement in South Africa, Manase (2005) on stories published in Staffrider as a counter discourse to apartheid narratives and Reid's (2021) analysis of Ivan Vladislavic's piece "Tsafendas's Diary" published in the magazine in 1988.

2 . Nhlabatsi has been briefly discussed by Seidman (2007:95) and Mason (2004:153, 2010:105).

3 . I am indebted to Muziwakhe Nhlabatsi who generously shared his time, work and memories with me.

4 . Pass laws were used to control the movement of Africans during the colonial and apartheid periods in South Africa. From 1952 all Africans older than 16 years were required by law to carry a reference book, or pass. In 1986 the pass laws were repealed (Johnson & Jacobs 2011:232-233).

5 . He recalls that as a youngster he had bought American comics and read the comics printed in the back of the Sunday Times (Nhlabatsi 2020b).

6 . Mason discovered underground comix by the likes of Gilbert Shelton and Robert Crumb, which would have a lasting influence on him, in the office of the student newspaper at the University of Natal during his time studying English during the seventies. 'Deeply inspired' Mason created "Vittoke in Azania", a satirical serialised strip for the student press, which was 'unashamedly derivative' of Crumb and Shelton (Mason 2010:85-86).

References

Aitchison, J. 2003. Struggle and compromise: a history of South African adult education from 1960 to 2001. Journal of Education 29:125-177 [ Links ]

ASAI. 2020. Muziwakhe Nhlabatsi. CV. [O]. Available: https://asai.co.za/artist/muziwakhe-nhlabatsi/ Accessed 19 July 2020. [ Links ]

Badsha, O. 2021. Biography. [O]. Available: https://www.omarbadsha.co.za/content/omar-badsha Accessed 5 November 2021. [ Links ]

Brown, J. 1990. Every picture tells a story, don't it? Radical History Review 1990(46- 47):425-435. [ Links ]

Chapman, M. 1999. African popular fiction: consideration of a category. English in Africa 26(2):113-123. [ Links ]

Espin, M. 2021. The 'Staffrider' figure and the reading of South African poetry. English in Africa. 48(2):23-42. [ Links ]

Figlan, M. 1982. Art and society Ntate Sekoto. Staffrider 5(2):38-39. [ Links ]

Gaylard, R. 2008. Writing black: the South African short story by black writers. Doctoralthesis, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Hill, S. 2015. Biko's ghost: the iconography of Black Consciousness. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Hill, S. 2018. Creating consciousness: Black art in 1970s South Africa. NKA Journal of Contemporary African Art November(42-43):196-210. [ Links ]

Hobbs, P & Rankin, E. 1997. Printmaking in a transforming South Africa. Claremont: David Philip. [ Links ]

Hobbs, P & Rankin, E. 2003. Rorke's Drift: empowering prints. Cape Town: Double Storey. [ Links ]

Johnson, K & Jacobs, S. 2011. Encyclopedia of South Africa. Boulder: Lynne Rienner. [ Links ]

Manase, I. 2005. Making memory: stories from Staffrider magazine and 'testing' the popular imagination. African Studies 64(1):55-72. [ Links ]

Mason, A. 2010. What's so funny? Under the skin of South African cartooning. Cape Town: Double Storey. [ Links ]

Mason, A. 2014. Interviews: a universal message. [O]. Available: http://ndmazin.co.za/media/interviews/ Accessed 5 November 2021. [ Links ]

Mason, A. 2021. About. [O]. Available: http://ndmazin.co.za/about/ Accessed 5 November 2021. [ Links ]

Mason, AJ. 2004. Black and white in ink: discourses of resistance in South African cartooning, 1985-1994. MA dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban. [ Links ]

Maughan-Brown, D. 1989. The anthology as reliquary? Ten years of Staffrider and the Drum decade. Current Writing: Text and Reception in Southern Africa 1(1):3-21. [ Links ]

Mofokeng, B. 1989, Where are the women? Ten years of Staffrider. Current Writing: Text and Reception in Southern Africa 1 (1):41 -43. [ Links ]

Ndebele, N. 1989. The writers' movement in South Africa. Research in African Literatures 20(3):412-421. [ Links ]

Nhlabatsi, M, graphic artist, Johannesburg. 2020a. Email exchange with author. 6 July. [ Links ]

Nhlabatsi, M, graphic artist, Johannesburg. 2020b. Interview by author. [Transcript]. 4 March. Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Nhlabatsi, M. 1979. Eye: Mzwakhe Nhlabatsi on visual arts. Staffrider 2(2):54-55. [ Links ]

Nhlabatsi, M. 2018. Comrades in the Arts and Culture - four decades ago. [O]. Available: http://muziwakhenhlabatsi.blogspot.com/2018/05/comrades-in-arts-and-culture-four.html Accessed 5 November 2021. [ Links ]

Oliphant, AW & Vladislavic, I. 1988. Preface, in Ten years of Staffrider 1978-1988, edited by AW Oliphant and I Vladislavic. Johannesburg: Ravan:viii-x. [ Links ]

Penfold, T. 2015. Volume, power, originality: reassessing the complexities of Soweto poetry. Journal of Southern African Studies 41(4):1-19. [ Links ]

Pretorius, D. 2021. Broadening the 'Black Consciousness Aesthetic': Muziwakhe Nhlabatsi's illustrations for Staffrider, 1979-1981. [O]. Available: https://asai.co.za/muziwakhe-nhlabatsi-Staffrider/ Accessed 5 November 2021. [ Links ]

Rankin, E. 2011. Creating communities: art centres and workshops and their influences on the South African art scene, in Visual century South African art in context vol 21945-1976, edited by L von Robbroeck. Johannesburg: Wits University Press:52-77. [ Links ]

Ravan. 1983. Staffrider magazine presents South Africa through the lens: social documentary photography. Braamfontein: Ravan. [ Links ]

Reid, K. 2021. Small and joined in print: Ivan Vladislavic, "Tsafendas's Diary," and Staffrider magazine (1988). Social Dynamics 47(2):264-287. [ Links ]

Rive, R. 1982. Books by black writers. Staffrider 5(1):12-15. [ Links ]

SACHED. 1990. Upbeat, part 2, plans for 1990. AG 2462. SACHED "Teaching with Upbeat". WITS Historical Papers, William Cullen Library. [ Links ]

Schauer Young, M. 2010. Resistance coded in comics: visual literacy in South Africa. MA dissertation, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. [ Links ]

Seidman, J. 2007. Red on black: the story of the South African poster movement. Johannesburg: STE Publishers. [ Links ]

Seidman, J. 2011. Finding community voice: the visual arts of the South African cultural workers movement, in Visual century South African art in context vol 3 1973 1992, edited by M Pissara. Johannesburg: Wits University Press:104-125. [ Links ]

Staffrider Magazines 1978-1993. [O]. Available: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/staffrider-magazine-1978-1993. Accessed 19 July 2020. [ Links ]

Tomaselli, K. 2019. Arts, apartheid struggles, and cultural movements. Safundi 20(3):338-358. [ Links ]

Trimbur, J. 2009. Popular literacy and the resources of print culture: the South African Committee for Higher Education. College Composition and Communication 61(1):85-108. [ Links ]

Upbeat Magazine. 1980-1994. Collection AG2462. SOUTH AFRICAN COMMITTEE FOR HIGHER EDUCATION (SACHED) 1961-1994. J1 Upbeat Magazine 1980-1994. WITS Historical Papers, William Cullen Library. [ Links ]

Vaughan, M. 1981. The stories of Mtutuzeli Matshoba: a critique. Staffrider 4(3):45-47. [ Links ]

Vaughan, M. 1984. Staffrider and directions within contemporary South African literature, in Literature and society in South Africa, edited by L White and T Couzens. Johannesburg: Longman:196-212. [ Links ]

Vaughan, M. 1985. Literature and populism in South Africa: reflections on the ideology of Staffrider, in Marxism and African literature, edited by GM Gugelberger. London: James Currey:195-220. [ Links ]

Wylie, D. 2008. Art+revolution: the life and death of Thami Mnyele South African artist. Auckland Park: Jacana. [ Links ]