Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.37 Pretoria 2023

https://doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2023/n37a20

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

At home in Harlem: The politics of domesticity in Faith Ringgold's The Bitter Nest

Debra Hanson

Faculty Affiliate, School of the Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Va. United States of America. hansondw@vcu.edu

ABSTRACT

The Bitter Nest, a sequence of five large-scale story quilts created in 1988 by Faith Ringgold (American, b. 1930), probes the dynamics of an imagined Black middle-class family, their home in Harlem, and the connections they forge within it. Originally conceived as a performance piece, the quilted series likewise expands on its themes of home, family, mother-daughter relations, and Black female creativity. Bringing together storytelling and quilting traditions prominent in the artist's family, the African American community, and across the African diaspora, The Bitter Nest extends the concept of home to encompass Harlem itself, connecting its residents and neighbourhoods across multiple generations.

Celebrated as a visual artist, author, educator, and lifelong advocate for social justice, Faith Ringgold, is among the most influential cultural figures of her generation. While major exhibitions showcasing the scope of her achievements have recently generated a welcome outpouring of new scholarship, The Bitter Nest remains surprisingly overlooked in literature on the artist. In examining the series' representation of the politics of domesticity, home, and family, this article aims to remedy this oversight as it expands the scope of critical discourse on the work of a major American artist, and directs renewed attention to Ringgold's powerful reimagining of the Black home and family in this series and throughout her oeuvre. Drawing on the artist's commentary on The Bitter Nest and related topics, the visual evidence of the quilts, and late twentieth-century and more recent feminist theory, this essay provides a foundation for further research into The Bitter Nest and its many contributions to the evolving story of Black women and families in America.

Keywords: Story quilts, domestic politics, mother-daughter relationships, the Black family, the Harlem Renaissance.

Introduction

The Bitter Nest, a sequence of five large-scale story quilts created in 1988 by Faith Ringgold (American, 1930-), probes the dynamics of an imagined Black middle-class family, their home in Harlem, and the connections they forge within it.1 Focusing on the challenges faced by Cee Cee, the free-spirited Prince family matriarch, as she strives to reconcile the demands of home and family with her creative ambitions, the series thematises race and gender in its examination of domestic politics, mother-daughter relationships, and the realisation of Black female creativity. Originally conceived as a performance piece, the centre panel of each Bitter Nest quilt features members of the Prince family reenacting key events from Ringgold's story (see Figure 1). Painted in acrylic on canvas, each panel is bordered by double columns of printed, dyed, and pieced fabric divided by passages of the written narrative. Unifying image and text in a single frame, Ringgold's quilts weave together storytelling and textile traditions prominent in her own family, the larger African-American community, and across the African diaspora. Centring the lives of Black women, real and imagined, past and present, they deliver the 'feminist critical commentary which considers the impact of race, class, and sex' called for by bell hooks (2007:329) with humour, insight, and imagination. Exemplifying the artist's commitment to politically engaged art practices based in, but not limited to, the domestic, familial, and feminine spheres, the quilts highlight the power and resilience of Black women and families while reversing the historical devaluation of objects, materials, and processes once identified exclusively as 'women's work.'

Celebrated as a visual artist, author, educator, and lifelong advocate for social justice, Faith Ringgold, is among the most influential cultural figures of her generation. While major exhibitions showcasing the scope of her achievements have recently generated a wealth of new scholarship, The Bitter Nest remains surprisingly overlooked in literature on the artist. In examining the series' representation of the politics of domesticity, home, and family, this article aims to remedy this oversight as it expands the scope of critical discourse on the work of a major American artist and directs renewed attention to Ringgold's reimagining of the Black home and family in this series and throughout her oeuvre. Drawing on the artist's extensive commentary on The Bitter Nest and related topics, the visual evidence of the quilts, and late twentieth-century, as well as more recent, feminist theory, the essay provides a foundation for further research into The Bitter Nest and its contribution to the evolving story of Black women and families in America.

Unma(s)king the canon

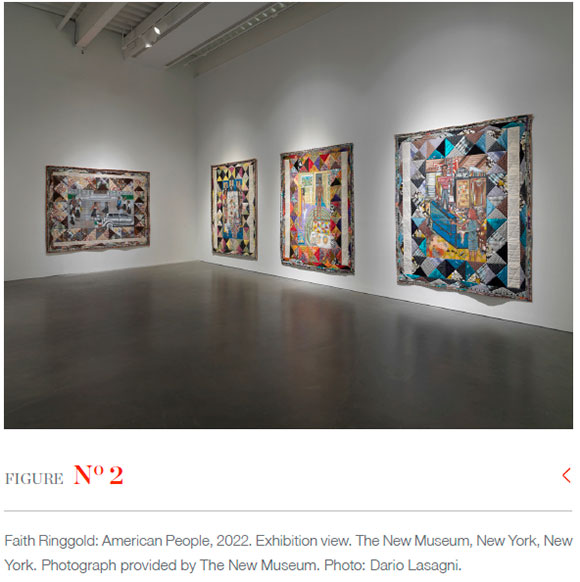

Executed on a scale that rivals that of academic history painting and mainstream modernism (see Figure 2), The Bitter Nest quilts insert the Black body into a Euro-American visual history from which it was long excluded. Disputing hierarchies of gender, aesthetic value, and race, they mix paint on canvas with fabrics, stitching, patchwork, and the written word, integrating methods of making traditionally viewed as separate. Thematising hybridity, they refute the categorisation of art genres, subjects, and mediums upheld by the Western canon,3 visually repeating a question posed by the artist: 'Who said that art is oil paint stretched on canvas with art frames? I didn't say that, and nobody who ever looked like me said that' (quoted in Farrington 1997:66).

Ringgold's statement alerts us to the significance of these painted quilts as sites of formal experimentation, art historical revision, and Black self-representation. Understood as both a political statement and an articulation of selfhood, the artist's claim to representational space allows for reversing past misrepresentations while restoring Black female visibility. The Bitter Nest Part II: The Harlem Renaissance Party (see Figure 1) pictures a gathering of Ringgold's venerable forebears in this effort: WEB Du Bois, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and their fellow 'coworkers in the kingdom of culture' (Du Bois 1903/2018:10). Their presence underscores the longevity of the struggle for Black self-representation taken up by the artist and the co-workers of her own and later generations.4

Much admired for their magical mix of colours, patterns, words, and textures, the story quilts communicate their political convictions in a medium used by generations of women to connect the domestic and public spheres and effect social action. Building on the scholarship of earlier feminists,5 Bryan-Wilson (2017:7-13) outlines a history of textiles as expressions of dissent and threats to the established social order. Ringgold's work continues this political history: quilting materials and techniques are central not only to the design and structure of each Bitter Nest image but to the series' social, political, and historical resonance. Referencing a matrilineal genealogy of making within the artist's own family, The Bitter Nest quilts also celebrate 'the original artists:' unnamed Black women, enslaved and free who, as Alice Walker (1974/2017:90) tells us, 'handed on the seed of a flower they themselves never hoped to see...'. As mementoes of these lost histories, quilts honour lives not otherwise recorded; they can also be understood as visual analogies for an African-American cultural heritage pieced together from images, words, objects, music, and memories dispersed across a global diaspora.

Among the first feminist artists to work extensively with textiles, Ringgold deployed this medium to challenge-in her activist art, and art activism-the gendered and racialised conventions, normalised within Western culture that marginalised quilts and the stories of those who produced them. In the social upheaval of the 1960s and 1970s, the delegitimisation of these conventions and the canon upholding them was one goal shared by the Feminist, Black Power, and Black Arts Movements. Positioned at their intersection, Ringgold evolved an aesthetic-political stance later termed Afrofemcentrism: 'an Afro-female centred worldview and its artistic manifestations' (Tesfagiorgis 1987:26). With its insistence on the primacy of Black female consciousness, this concept aligned with the artist's commitment to representing the full complexity and humanity of Black women and families, and with her opposition to one aspect of the liberation movements (named above) that she in other ways supported: their marginalisation of Black women. Expanding the canon while working to hasten its demise, painted quilts/quilted paintings such as The Bitter Nest proved to be ideal vehicles for interrupting art history 'by a political voice', and forcing a reconceptualisation of its aesthetic criteria (Pollock 1999:2325; Wallace 2004:190-191).

The feminist story-quilt nexus

Ringgold's turn to fabric in the early 1970s was, then, based in political, as well as familial, aesthetic, and practical considerations. Although the 1967 exhibition of her first mature paintings, The American People Series, was well received, few professional opportunities arose in its aftermath. Cognisant of how the canvases' unique figurative style and polemical content departed from mainstream art of the sixties, Ringgold was equally aware of the racial and gender biases of the art world, which mirrored those of the nation at large (Ringgold 1995:143-144;154-155).6 In response, she spearheaded a series of protest actions aimed at New York's museum and gallery culture, and seeking alternative audiences and markets for her work, she began a series of lectures and exhibits at colleges and universities outside New York City. While the portability of fibre aided in this venture, her move away from oil on canvas was more directly influenced by family precedents. Marking the advent of Ringgold's artistic collaboration with her mother, the couturier Mme Willi Posey, and through her, the artist's great and great-great grandmothers, enslaved quilters Betsy Bingham and Susie Shannon, the shift to fibre-based arts honours her own female forebears, as well as the unnamed artists cited in the preceding section of this essay. Other factors included the artist's desire to distance herself from a painting medium so deeply embedded in institutional hierarchies, and realise her ambition to write and publish stories, whether on cloth or in books (Ringgold 1990:12).

The shift to fibre connected Ringgold's work to global, as well as familial craft traditions. The African masks, textiles, and sculpture she knew through self-directed study and later trips to Nigeria and Ghana became her 'classical' art forms; 'instead of looking to Greece,' she said, 'I looked to Africa' (Ringgold 1994:3).7 Tibetan Buddhist thangkas, the scroll-like paintings on silk that she discovered at Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum in 1972, were another catalyst in her development. While no doubt drawn to their visual impact and cultural significance, the indigenous origins of these objects also accorded with Ringgold's ongoing critique of the race and gender-based exclusions of Western art institutions and histories. Enlisted as allies in this project, quilts proved an effective platform for reversing the historical misrepresentation and/or erasure of the raced female body. Moving away from the Eurocentric focus of her own education while advancing Black feminist priorities, Ringgold utilised non-traditional materials to reimagine female identities and possibilities.

The Slave Rape Series (1972), modelled by the artist and her daughters, was among the artist's first thangka-inspired pieces. Exploring explicitly feminist themes from a position of Blackness, these 'political landscapes' thematise female resistance to the horrors of the African slave trade by recasting their subjects as agents of active resistance rather than passive victims. While staged in historical terms, the series' contemporary resonance is clear. 'Everything in my life,' Ringgold explains, 'has to do with the fact that I am a black woman...I am struggling against being a victim, which is what black women become in this society' (quoted in 1990:140). Reimagining the past from a militant feminist perspective, The Slave Rape Series uses fragments of fabric to piece together fragments of a past that lives on in the present. Importantly, it also marks the artist's first collaboration with her mother, a partnership that by 1980 resulted in the creation of her first story quilt, the art form for which Ringgold is now best known.

Performing The Bitter Nest

Dolls, masks, and the first multimedia performance piece soon followed. Aptly described as a 'funereal tableau,' The Wake and Resurrection of the Bicentennial Negro (1976) combined masks, paintings, and life-size soft sculptures with music, stories, and group performance. Inspired by 'African traditions of combining storytelling, dance, music, costumes and masks in a single production,' Ringgold explains that 'performance for me was simply another way to tell my story' (Ringgold 1995:238).8

While staging Wake and Resurrection required six or more performers, The Bitter Nest was enacted solely by the artist (see Figure 3). For one performance, the artist, 'dressed in colorful quilted costumes and wearing masks and headdresses, did a pantomime to the pre-recorded sound of her own voice narrating the story. Throughout the performance she remained silent and the only stage props were 10 quilted bags' (Gouma-Peterson 1990:28). While props and settings appear to have varied, the narrative did not. In part an exploration of the mother-daughter tensions in her own life, the artist conceived The Bitter Nest to 'give Mother a voice,' although, ironically, she created 'a mother who was both deaf and dumb' (Ringgold 1995:240;241). The complexity of the artist's self-referential story reminds us that domestic politics are never confined to the domestic realm. Rather, home and family-in this case, the Black family in America-live within a tangled web of societal prejudices and pressures, patriarchal politics, and the ever-present weight of history.

The Bitter Nest, Part I: Love in the Schoolyard

Once upon a time, there was a young black woman doctor named Celia Prince. Her father, Dr Tercel T Prince, was a socially prominent black dentist in 1920s Harlem. Celia's mother, Cee Cee, a loving wife and mother, was a marvellous cook and homemaker known for her unusually decorated home and the unique pierced and quilted bags she filled it with...

Celia's family lived in a large townhouse on Harlem's Strivers Row, a tree-lined street famous for its beautiful brownstones owned by Harlem's fashionable 400... In line with her family's wishes, Celia went to Howard University and graduated first in her class with a degree in medicine. Her office was in the family brownstone... despite her successful career, her personal life was bittersweet.

The dentist, already an old man by the time Celia was born... first saw Cee Cee in the yard of the Junior High School near his office. Gathering the books she dropped, he put them back in her case and offered her a lift home... [and then] came every day at dismissal time to drive her home. The other girls gathered around to see him driving such an expensive car. Cee Cee told them he was her uncle... soon he invited Cee Cee to his house, and she went... And then she got pregnant... the baby was a beautiful girl named Celia. After giving birth, Cee Cee developed a deafness in both ears... (Witzling 1991: 362).9

So begins the Prince family history recorded in the borders of Love in the Schoolyard (see Figure 4). Initially framed as a 'once upon a time' tale describing a seemingly ideal family, the story soon takes a more sobering turn, raising troubling questions about the relationship between a then-fourteen-year-old girl and a much older man. Congruent with The Bitter Nest's performative origins, facial expressions and body language communicate the narrative's emotional weight. Contrasting with its darker surroundings, the light grey grid at the image's centre repeats the geometric structure of the quilted borders and the entire composition, thereby unifying the visual field while highlighting the drama unfolding on the improvised 'stage' of the sidewalk. As Cee Cee and the dentist gravitate toward one another, their gazes lock, their hands (almost) touch, and their fate appears to be decided. Costumes, props, and setting- the schoolgirls' uniforms and racial identities, Dr Prince's flashy car, and even the name of Cee Cee's school-Harriet Beecher Stowe Junior High--establish the time (the 1920s) and place (Harlem, where the school is still located) of the scene, grounding Ringgold's engaging mix of realism and fantasy in its historically specific context.

In contrast to the other Bitter Nest quilts, the cool grey tonalities dominating Love in the Schoolyard create an air of apprehension that is reinforced by the suspicious expressions and tense postures of Cee Cee's classmates (see Figure 5). Flanking the central figures, they function much like the chorus in an ancient Greek tragedy, warning of the future consequences of the protagonists' impending actions.

Although not portrayed as a villain per se, Dr Prince's actions identify him as a symbol of patriarchal privilege and control, if not statutory rape and child abuse (in 1920, the age of consent in New York was eighteen). Despite Ringgold's claim that her work does not depict 'people doing really bad things to each other' (Ringgold 1990:12), his romantic pursuit of an underage girl calls to mind a history of Black female sexual exploitation, and of girls forced into adulthood while still children.10

The apparent absence of Cee Cee's parents is noteworthy; it is surely no accident that her school is named after Harriet Beecher Stowe, the abolitionist author who brought the separation of enslaved families to national attention in her 1852 novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. Situating The Bitter Nest's origin story in its larger historical context, Ringgold evokes a past still alive in the 1920s as well as the present day. While the narratives and characters in her quilts are fictional, they address issues, events, and conditions that are real, or could be. Cee Cee may be a fictional character, but the trauma of sexual manipulation and motherhood at such a young age speaks to a known reality of women's lives.

The Bitter Nest, Part II: The Harlem Renaissance Party

In The Harlem Renaissance Party (see Figure 1 and Figure 6), the mood shifts dramatically. Celia (seated, lower left), now a young adult, looks on as her mother occupies centre stage at the gathering she hosts. Decorated in a dazzling array of colours and patterns, the interior of the family brownstone associates domestic space with aesthetic beauty and physical comfort; their repetition in Cee Cee's exotic outfit accentuates her immersion in the environment she has created. Her identification with this space and the 'women's work' required to create it contests Betty Friedan's claim that domestic activities generated only a sense of emptiness and displeasure in women. In contrast, bell hooks (2000:2;133-134) insisted that 'many [Black]women longed to be housewives,' to participate in the 'humanizing labor' of the home that 'affirms their identity as women,'--the labour disparaged by Friedan-as opposed to 'dehumanizing and stressful' labour outside the home. In this view, the household is configured as a unit of power, and women are empowered within it.

While Cee Cee may be, as Ringgold's narrative tells us, a marvellous cook and homemaker, her daughter bemoans the fact that that this does not prevent her from engaging in behaviours that knowingly transgress social boundaries. In The Bitter Nest, the unique objects and interiors Cee Cee crafts exemplify the multivalent possibilities of 'women's work'; rather than upholding ideals of genteel femininity, they subvert them (Parker 1984:ix). Like Ringgold's story quilts, Cee Cee's creations (and persona) serve as weapons of resistance rather than signs of acquiescence to patriarchal constraints, and domestic production becomes not a sign of emptiness but a tool of self-realisation. Reimagining art, female creativity, home, and family as points of intersection rather than mutually exclusive endeavours, The Harlem Renaissance Party argues for a more expansive vision of feminism as 'a struggle to eliminate all forms of oppression' (hooks 2000:42).

While the outward motions of Cee Cee's arms and skirts-resembling those of an exotic bird about to take flight-punctuate her integration with the surrounding space, the body language of her daughter tells a very different story (see Figure 6). Her reserved, self-contained deportment, conservative manner of dress, and disapproving facial expression all convey her discomfort as

Cee Cee put on a show that topped off the evening... dressed in her oddly pieced and quilted costumes, masks, and headdresses, she moved among the illustrious guests to music only she could hear. They thought of her as an eccentric undiscovered original....

Celia was very disturbed by Cee Cee's odd looking patterns... and made it a point to let [everyone] know it. My mother is a family disgrace [she said]... the only hope I have... is to get out of here and become a doctor... As far as I am concerned, she is crazy like her quilts.

Celia got older and went off to college and came home a doctor. Cee Cee was still right there making bags and dancing to music only she could hear.11

Seemingly unperturbed by her daughter's disapproval, Cee Cee's 'crazy' exuberance is echoed in the formal structure of The Harlem Renaissance Party. Supplanting the subdued tonalities of Love In the Schoolyard, strong contrasts of light and dark enlivened by jewel-like accents of deep red and blue activate Party's central panel and border. The triangle-within-a-rectangle pattern used throughout the series (see n. 7) echoes the quilt's underlying geometry; repeated colours and patterns likewise add to the composition's unity and variety. Ringgold likens these rhythmic repetitions to the polyrhythms of African drumming adapted in American jazz (Ringgold 1995:189). Evoking the rhythm and energy of jazz in visual form, The Harlem Renaissance Party speaks to the image's historical context: the Jazz Age of the 1920s, at its zenith in Harlem.

The attendees-from left to right: Florence Mills, Aaron Douglass, Meta Warrick Fuller, WEB DuBois, [Dr Prince], Richard Wright, Countee Cullen, Zora Neale Hurston, Alain Locke, and Langston Hughes-are among the leading luminaries of the vibrant period of Black intellectual, cultural, and artistic achievement known as the Harlem Renaissance. Known to Ringgold as a child growing up in Harlem in the 1930s and 40s, these individuals were role models for her own artistic and literary accomplishments. At its height in the 1920s, it marked the first unified assertion of 'race pride' and Black cultural identity on a national scale. In his 1925 essay 'The New Negro,' Alain Locke identified the 'new spirit' then emerging in Harlem, and Ringgold concurs that 'Black people did not define themselves until the 1920s... that was the first time there was an African American aesthetic, and a [true] image of ourselves' (Ringgold 1994:17). The poet Langston Hughes summarised this aesthetic: 'We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased, we are glad, if they are not, it doesn't matter. We know we are beautiful, and ugly too' (Hughes 1926/1995:95).

The distinctive objects Cee Cee displays in The Harlem Renaissance Party, including her African-inspired mask and garment, align her with this new spirit. Because she cannot speak, her creations speak for her; more than just exotic objects, they are meaningful expressions of her 'individual dark-skinned self' and the history it references. With her unique creations, self-fashioning, and choreography, performed to music only she can hear, Cee Cee claims her place in the cultural enterprise led by her illustrious guests.

The Bitter Nest extends the concept of home to Harlem itself, connecting its residents and neighbourhoods, real and imagined, across time and space. 'Harlem born and bred,' Ringgold has produced a substantial body of work on this topic alone: story quilts such as Echoes of Harlem (1980) and Street Story Quilt (1985), and more recently, Flying Home: Harlem Heroes and Heroines (1996, see Figure 7), an environmental scale glass mosaic mural installed on the platforms of Harlem's 125th Street subway station.12 Celebrating the legendary people and places that once made Harlem the cultural capital of Black America, Flying Home pictures many of the individuals featured in The Harlem Renaissance Party. Like this story quilt and Ringgold's 2015 children's book of the same title, the mural bears witness to the power of community-as-family and its ability to inspire and empower future generations. Soaring above key landmarks such as the Studio Museum of Harlem, the Apollo Theatre, and the Harlem Opera House, its figures in flight symbolise the new spirit praised by Locke, and the possibility of 'a new birth of freedom,' even in the face of a history of prejudice and injustice. The period's enlarged perspective included a growing awareness of the African-American community's relationship to a global, pan-African family, and to the centrality of Africa in the new cultural and political landscapes emerging in Harlem and other US cities. In The Bitter Nest, home is represented not as a singular idea or structure, but as a dynamic interchange of self, community, and world in which the meaning of family reverberates on multiple levels.

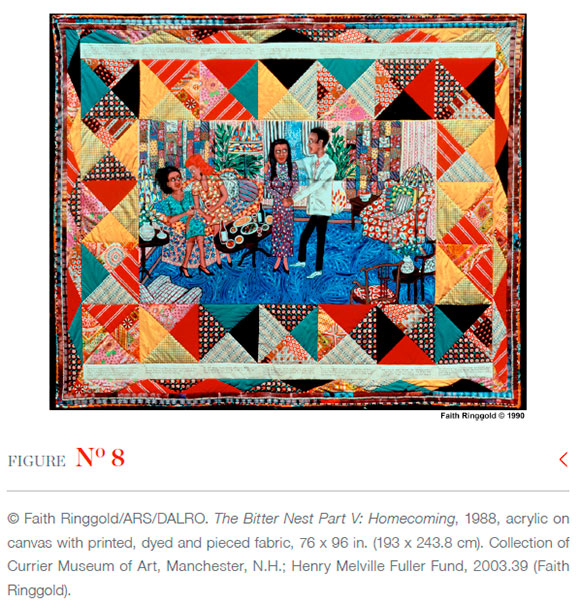

The Women

Like the majority of Ringgold's oeuvre, The Bitter Nest is self-referential in that it is based in personal experience but does not represent it directly. As a fictionalised response to the parental politics of her own household, The Bitter Nest reflects her efforts in the 1960s to come to terms with two rebellious teenage daughters while advancing her own career as a professional artist. 'Through art', she explains, 'I tried to create the peace we could not achieve in real life' (Ringgold 1995:96).13Although the lush interior and smiling family members featured in The Bitter Nest, Part V: Homecoming (see Figure 8) depict the peaceful reconciliation Ringgold sought, other scenes in the series paint a more troubled picture. While celebrating the home as an epicentre of Black family life, the contradictions expressed in the series' title are equally evident: home as a sheltering and protective nest, but also a site of bitterness, misunderstanding, and division. In The Bitter Nest, these tensions are heightened by the medium in which they are visualised. Most often associated with domestic solace and warmth, Ringgold's quilts convey very different meanings at times.

Like all family-related topics, the complexity of mother-daughter relationships is a matter of universal concern, irrespective of geographic, cultural, or racial differences. Viewed from this perspective, the 'normal' conflict of Cee Cee and Celia can be understood as affirming the humanity and diversity of Black life: its beauty but also its less pleasant aspects, its joys as well as its sorrows. Before the late twentieth century, affirmative images of the Black family were rare in American painting and sculpture.14 In the antebellum decades, with marriages of enslaved persons and any resulting offspring denied all legal protections, widely-circulated images of slave auctions represented not the preservation of family but its dissolution.15 In representing the Prince home as a locus of professional and artistic achievement, material comfort, and-even in moments of bitterness-familial love, Ringgold reverses the historical erasure of the Black family as a stable social and economic unit. 'That's all we're trying to do,' she asserts, 'give our lives a broad context and not limit ourselves to somebody else's idea of who we are' (Ringgold 1994:12).

While bearing no small resemblance to the artist herself (see Figures 3 and 6), The Bitter Nest's chief heroine can also be understood in relation to Celie, the protagonist of Alice Walker's 1982 novel The Color Purple. Ringgold conceived her Purple Quilt (1986), depicting characters from the novel framed by sections of its text, as a tribute to Walker and the power of her writing.16 The parallels between Walker and Ringgold's narratives are striking: both feature Black women who, despite their contrasting lifestyles-one lives in material comfort, the other in rural poverty-are subject to sexual exploitation at a young age, and are subsequently unable, or refuse, to speak. Both find ways to overcome these traumas and achieve independence through their own strengths and talents, and both find their voices-metaphorically and in actuality-through sewing and the fibre arts, forms of 'women's work' they subsequently build into successful businesses. By the conclusion of their stories, each attains a sense of self-fulfilment that honours the unrealised creativity of past generations of Black women, the original artists, mothers and grandmothers who, Walker tells us, 'might have been Poets, Novelists, Essayists...,' or perhaps a quilter, '[leaving] her mark in the only materials she could afford, and the only medium her position in society allowed her to use' (Walker 1974/2017:86-87;90).

As a textile and performance artist, Cee Cee also shares strong affinities with her creator. Ringgold's silence while performing The Bitter Nest mimics that of her heroine, and as a child, she recalls making 'outlandish looking pocketbooks I would sew together...from scraps of fabric or pieces of pattern...[Mother]had discarded...': the direct antecedents of Cee Cee's 'eccentric' bags, masks, costumes, and other creations (Ringgold 1995:71).

This cluster of woman-centred ideas and identities speaks to the 'special feminist critical commentary' sought by hooks (2007:329) and realised in the work of Ringgold and Walker. The linguistic similarity of their protagonists' names-Celie, Celia, and Cee Cee-directs attention to the female synergies manifest in their narratives and a larger network that extends to the artist, the writer(s), and their own family histories. Whether through their affinities or differences, each enhances our understanding of the others and their place in an interwoven history of quilting, sewing, storytelling, women, and families. When asked by an interviewer if Celia and Cee Cee reflected her relationship with her own mother, Ringgold's response was: 'Yes, that's all of us, that's me and my daughters, that's me and my mother (Ringgold 1994:11). For Ringgold, 'all of us' encompasses a fellowship of women past and present who search for their mother's gardens, and support one another in their mutual efforts to 'make the unknown thing that [is] in them known' (Walker 1974/2017:86).

The Bitter Nest, Part V: Homecoming

The Bitter Nest, Part III: Lovers in Paris, and Part IV: The Letter shift the focus to Celia, now a successful doctor, but still estranged from her mother. After rejecting other potential suitors, Celia meets Victor, a duplicitous lawyer. Their courtship takes her from New York City to Paris, where they become lovers. Celia becomes pregnant, and Victor deserts her; heartbroken, she returns to New York and bears a son out of wedlock. Cee Cee decorates a beautiful nursery for her grandson and supports Celia's wish to keep the baby, but Dr Prince refuses, claiming that his presence would disgrace the family. Now abandoned by two men, Celia's opinion of her father is forever changed, and she rethinks her relationship with her mother. Percel, her son, goes to live with her friend Mavis, who raises him as her own child. In Part IV: The Letter, he discovers love letters from Celia to Victor, revealing the truth of his parentage. Soon thereafter, Dr. Prince dies, Cee Cee inherits the brownstone, and invites her daughter, grandson, and Mavis to join her there. In the final Bitter Nest quilt, Homecoming (Figure 8), the visual and material abundance of the family's no-longer-bitter nest-its joyous choreography of colour, pattern, food, wine, plants, fabric art, furniture, and family members, framed by an exuberant patchwork border- amplifies the emotive power of the figures' eloquent body language and facial expressions.

In this author's reading, The Bitter Nest represents two visions of home and family- the first in effect during Dr Prince's life, the second following his death; the phases of Cee Cee and Celia's relationship follow a similar pattern. The 'first' Prince family home, a nuclear family headed by a male breadwinner, exemplifies patriarchal control. Alluded to earlier in The Bitter Nest narrative-recall the doctor's assault/ rape of then fourteen-year-old Cee Cee-this impression is reiterated in The Harlem Renaissance Party (Figure 1). Dr Prince looms over the gathering at the head of the table (the fifth figure to Celia's right), his stern visage reinforcing his dominant size and placement.17 In this domestic model, Celia remains alienated from her mother and aspires to emulate her father by becoming a doctor.

Following her husband's death, Cee Cee is free to restructure the Prince home according to matrilineal principles. Liberated from his patriarchal authority and with ample financial means, she shifts the household from a male to a female-centred, multigenerational paradigm. Mavis, Percel's 'othermother,'18 is welcomed into the family, Cee Cee and Celia are reconciled, Cee Cee suddenly regains the ability to hear and speak, and opens a studio selling her fabric creations.

While addressing issues experienced directly by the artist, this imagined sequence of events and outcomes engages with socio-political discourse of the period. In the 1980s, as The Bitter Nest was conceived and executed, mother-daughter connections became a major focus of feminist theory. Rejecting what O'Reilly (2000:144) identifies as 'the patriarchal script of mother-daughter relations'-the belief that daughters must distance themselves from their mothers to achieve adult autonomy-emphasis shifted to the link between mother-daughter bonding and female empowerment. A crucial point in this regard is the connectedness of a mother's empowerment to that of her daughter-i.e., their mutuality, since the mother cannot effectively model a sense of empowerment and independence that she herself does not possess. While O'Reilly (2000:147) cites these ideas as 'quite recent' among Anglo-American feminists, she notes that they were long accepted 'as central to both black and female emancipation'... in African-American communities.

Although outlined here only in the broadest of terms, these concepts are reflected in The Bitter Nest's concluding segments. Under Dr Prince's authority, Celia follows the 'patriarchal script' that claims mother-daughter division as a prerequisite for female autonomy. In contrast, the matrifocal model initiated in his absence facilitates the renewal and strengthening of the mother-daughter bond, in part because it allows Cee Cee to fully realise her own independence. The immediate restoration of her speech and hearing following his death suggests that these conditions were protective mechanisms adopted in reaction to the trauma she experienced while still a young girl. In her self-imposed isolation and through her many creative efforts, she achieved at least some degree of autonomy in the only way she could. As Ringgold (1994:11) confirms, 'that was her way, and she found the courage to do it':

Her muteness was the way to get past her husband the doctor, and all of what he was in a time when women weren't important, and social standards were very important. So she had a very difficult time. I'm saying that maybe[Cee Cee] was never deaf, maybe she just pretended to be deaf to get the attention, in order not to kill herself. A lot of women... go crazy. [Cee Cee] found a way to live her life, which is what everybody's trying to do anyway (Ibid).

Conclusion

Just as the story of The Bitter Nest began with 'once upon a time', its final chapter appears to conclude with 'happily ever after'. Tracing the arc of Cee Cee and her family over time-through major life events such as courtship, marriage, childbirth, motherhood, and death-Ringgold's multi-layered narrative imagines the 'new,' woman-centred Prince household as an evolving, generative network in which three generations of a Harlem family live, grow, change, create, and ultimately thrive. The politically-informed vision of the series continues the historical project of claiming for Black individuals, families, and communities an inclusive and fully humanised space within the American social, political, and cultural enterprise. In light of this project's continued relevance and urgency, this essay provides an important foundation for continued research into the richly complex visual and textual narrative of The Bitter Nest, and its many contributions to the evolving story of Black women and families in America.

Notes

1 Story quilts tell stories, record historical events and persons, or mark significant milestones; The Bitter Nest does all of these. The African-American story quilt tradition can be traced to Harriet Powers, a nineteenth-century (enslaved, later free) quilter famed for her original designs picturing Biblical stories and nature motifs. Story quilts are the art form for which Ms. Ringgold is now best known.

2 The most recent major exhibitions of Ringgold's work are 'Faith Ringgold' (June 2019-October 2021), at London's Serpentine Gallery, Sweden's Bildmuseet, and the Glenstone Museum in Potomac, Md.; 'Faith Ringgold: American People' (February-November 2022) at New York's New Museum and the de Young Museum in San Francisco; and 'Faith Ringgold: Black is Beautiful' currently on view at the Musée Picasso, Paris. Although the Glenstone and New Museum catalogues feature new scholarship, none mentions The Bitter Nest, and only the New Museum catalogue reproduces images of these quilts. To date, brief analyses of the series can be found only in two articles by Thalia Gouma-Peterson from 1990 and 1998.

3 Pollock (1999:3) defines a canon as 'the retrospectively legitimating backbone of a political and cultural identity, a consolidated narrative of origin, conferring authority... '

4 The full quotation: 'This, then, is the end of his [the Negro's] striving, to be a co-worker in the kingdom of culture...to husband and use his best powers and latent genius.' The struggle for cultural visibility has a much longer history; see n.14 on Frederick Douglass and photography.

5 See Parker (1984); Pollock (1999); Parker and Pollock (1992); Lippard (1995). See also Mainardi (1974).

6 On the general situation of Black artists in this period, see Bearden (1969). On Black women artists in this period, see Brown (1972).

7 Ringgold (1990:12) cites 'the inspiration of African art' as her reason for making quilts. In this quote the artist notes this influence in general, pan-African terms; more specific references identifiable in The Bitter Nest include: the 'triangle in a square' decorative motif in the quilts' borders, and the elongated/abstracted proportions and large heads of the figures; both derive from Kuba culture (Central Africa), the figures reference Kuba ndop sculpture in particular. The long narrow strips of cloth in The Bitter Nest borders recall West African/Yoruba prototypes in which such strips were sewn or tacked together to create banners, wall hangings, and ceremonial attire (see Wahlman 2001). Known forms of pre-colonial African quilting include quilted armour of the south Sahara region and ceremonial attire of Berber/North African origin (see Picton and Mack 1989:182-184.

8 For a full account of Ringgold's struggle to tell her story in words as well as images, see Hemmings (2020). After many years of searching for a publisher, her autobiography, We Flew Over the Bridge (originally titled Being My Own Woman, hereafter referred to as WFOTB), was published in 1995.

9 The quotation is an edited excerpt from Ringgold's quilt story written in the borders of The Bitter Nest, Part I: Love in the Schoolyard and reprinted in Witzling (1991:362).

10 In 1920, the legal age of consent in New York was eighteen. On the 'adultification bias' Black girls are still routinely subjected to, see Epstein, Blake and Gonzalez (2017).

11 The quotation is an edited excerpt from Ringgold's quilt story written in the borders of The Bitter Nest, Part II: The Harlem Renaissance Party and reprinted in Witzling (1991:362-363). Recall that Cee Cee had been deaf and mute since Celia's birth.

12 The mural is a part of the New York City Metropolitan Transit Association's Arts for Transit programme.

13 See Chapters Four and Five of Ringgold's 1995 autobiography, WFOTB, for an account of her relationship with her mother, Willi Posey, and her daughters, Barbara and Michele Wallace. Wallace (2004:101-103;108-109) offers her own memory of their family life in the late 1960s and the experience of following her mother's lead as a committed feminist.

14 They were, however, more readily available in photographs. The large body of work produced by Harlem-based photographer James Van Der Zee beginning in the 1920s is but one example of the more egalitarian visual record produced in this medium. As early as 1861, in a lecture entitled 'Pictures and Progress,' Frederick Douglass cited the power of photography to challenge racist stereotypes and generate alternative images of Black subjects.

15 See, for example, John Rogers' Slave Auction (plaster tabletop sculpture, 1859), and Eyre Crowe's Slaves Waiting for Sale: Richmond, Virginia (oil on canvas, 1861).

16 Witzling (1991:361). This is the only story quilt by Ringgold whose narrative was not written by the artist.

17 Other figures are also enlarged, due primarily to Ringgold's use of what might be termed reverse perspective: objects at the top of her images, rather than diminishing in size and clarity, often appear larger than those below. However, this size differential is particularly noticeable among the three family members due to Dr Prince's location directly above Cee Cee and Celia.

18 Othermothers, individuals who parent children not their own, have been central to the institution of African American mothering practices, often due to the biological mother's financial need to work outside the home, but also to the prevalence of multigenerational households and kinship exchange networks (Collins 1991:43-44). In Celia's case, the need for Mavis to raise Percel is directly linked to Dr Prince's refusal to allow him into the Prince's home-i.e., his patriarchal beliefs.

References

Auther, E. 2010. String felt thread-The hierarchy of art and craft in American art. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Bearden R., 1969. The Black artist in America: A symposium, in The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 27(5). [ Links ]

Broude, N & Garrard M (eds). 1973. Feminism and art history: Questioning the litany. New York, NY: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Brown, K., 1972. Where we at-Black women artists. Reprint in We wanted a revolution: Radical Black women 1965-1985. A sourcebook, edited by C Morris & R Hockley. New York, NY: The Brooklyn Museum:62-66. [ Links ]

Bryan-Wilson, J. 2017. Fray: Art + Textile politics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Collins, P. 1991. The meaning of motherhood in Black culture and mother-daughter relationships, in Double stitch: Black women write about mothers and daughters. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. [ Links ]

Du Bois, WEB. 2018 [1903]. The souls of black folks. Bloomfield, MI: Myers Educational Press. [ Links ]

Epstein, R, Blake, J & Gonzalez, T. 2017. Girl interrupted: The erasure of black girls' childhoods. Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality. [O]. Available: https://genderjusticeandopportunity.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/girlhood-interrupted.pdf. Accessed 10 February 2023. [ Links ]

Farrington, L. 1997. The early works and the evolution of the Thangka paintings. PhD Dissertation, City University of New York. [ Links ]

Gioni, M & Carrion-Murayari, G (eds). 2022. Faith Ringgold American People. Exhibition catalogue. New York, NY: New Museum. [ Links ]

Gouma-Peterson, T. 1990. Modern dilemma tales: Faith Ringgold's story quilts, in Faith Ringgold: A 25-Year survey. Exhibition catalogue. Hempstead, NY: Fine Arts Museum of Long Island:23-32. [ Links ]

Gouma-Peterson, T. 1998. Faith Ringgold's journey from Greek busts to African American dilemma tales, in Dancing at the Louvre Faith Ringgold's French Collection and Other Story Quilts. Exhibition catalogue. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press:39-48. [ Links ]

Hemmings, J., 2020. That's not your story: Faith Ringgold publishing on cloth. Parse, 11. [ Links ]

hooks, b. 2000. Feminist theory from margin to center. Cambridge, MA: South End Press. [ Links ]

hooks, b. 2007. Aesthetic inheritances: history worked by hand, in The Object of labor: Art, cloth, and cultural production edited by J Livingstone & J Ploff, J. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press:326-332. [ Links ]

Hughes, L. 1926. The negro artist and the racial mountain. 1995 Reprint in The Harlem Renaissance reader, edited by DL Lewis. New York, NY: Penguin Books:91-96. [ Links ]

Lewis, DL (ed). 1995. The Harlem Renaissance reader. New York, NY: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Lippard, L. 1995. The pink glass swan: Selected feminist essays. New York, NY: New Press. [ Links ]

Livingston, J & Ploff, J (eds). 2007. The Object of labor: Art, cloth, and cultural production. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Mainardi, P. 1973. Quilts: The great American art. 1984. Reprint in Feminism and art history: Questioning the litany, edited by N Broude & M Garrard. New York, NY: Harper & Row:330-346. [ Links ]

Morris, C & Hickley, R (eds). 2017. We Wanted A Revolution Radical Black Women 1965-85 A Sourcebook. New York, NY: The Brooklyn Museum. [ Links ]

Morrison, T. 1971. What the black woman thinks about women's lib. The New York Times Magazine, August 22:14-15;63-66. [ Links ]

O' Reilly, A. 2000. I come from a long line of uppity irate black women: African-American feminist thought on motherhood, the motherline, and the mother-daughter relationship, in Mothers and Daughters: Connection, Empowerment and Transformation, edited by A O'Reilly& S Abbey. New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers:143-159. [ Links ]

O'Reilly, A & Abbey, S (eds). 2000. Mothers and Daughters: Connection, Empowerment and Transformation. New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [ Links ]

Parker, R. 1984. The subversive stitch: Embroidery and the making of the feminine. London: Women's Press. [ Links ]

Parker, R. & Pollock, G., 1992. Old mistresses: Women, art, and ideology. London: Pandora. [ Links ]

Picton, J & Mack, J. 1989. African textiles. New York, NY: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Pollock, G. 1999. Differencing the canon-Feminist desire and the writing of art's histories. London & New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ringgold, F. 1995. We flew over the bridge. New York, NY: Little, Brown & Co. [ Links ]

Ringgold, F. 1994. The freedom to say what she pleases: A conversation with Faith Ringgold. Transcript of interview by Melody Graulich and Mara Witzling. NWSA Journal, 6(1):1-27. [ Links ]

Ringgold, F. 1990. Interviewing Faith Ringgold/A contemporary heroine. Interview by Eleanor Flomenhaft, in Faith Ringgold: A 25-Year survey. Exhibition catalogue. Hempstead, NY: Fine Arts Museum of Long Island:7-16. [ Links ]

Walker, A. 1974. In search of our mother's gardens: The creativity of black women in the South. 2017 Reprint in We wanted a revolution. Radical black women 1965-85. A sourcebook, edited by C Morris & R Hockley. New York, NY: The Brooklyn Museum. [ Links ]

Wallace, M. 2004. Dark designs and visual culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Wahlman, M. 2001. Signs and symbols: African images in African American quilts. New York, NY: Penguin:36-40. [ Links ]

Witzling, M (ed). 1991. Voicing our visions. Writings by women artists. New York, NY: The Women's Press. [ Links ]

Wong, H. 2018. Picturing identity: Contemporary American autobiography in image and text. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. [ Links ]