Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SA Orthopaedic Journal

On-line version ISSN 2309-8309Print version ISSN 1681-150X

SA orthop. j. vol.24 n.2 Centurion 2025

https://doi.org/10.17159/2309-8309/2025/v24n2a3

SPINE

The practice of skeletal traction for cervical spine dislocations in district hospitals in the Western Cape

Shayan ParbhooI; Bijou SalenceII; Justin SimpsonII; Schalk van der MerweII; Nicholas KrugerII,

IOrthopaedics Department, George Hospital, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIOrthopaedic Research Unit, Groote Schuur Hospital, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Cervical spinal cord injuries are common worldwide, and early intervention improves neurological outcomes. Not only is emergent closed cervical reduction best medical practice for these injuries, particularly facet dislocations, but South Africa has a unique situation where the apex court requires low energy cervical dislocations to be reduced within four hours of injury. As a result, district hospitals have a vital role in acute management of these injuries, especially where there are great distances to tertiary hospital referral centres and expected delays in patient transfers. This study aimed to assess the knowledge, resources and practice of closed cervical reduction in district hospitals in the Western Cape province of South Africa, and change in practice since the court ruling.

METHODS: This was a retrospective comparative study. District hospitals were identified using the Western Cape public hospital listings. A survey was prepared using Google Forms, and emergency room clinicians were emailed the online survey in 2023. Responses were compared to a similar survey conducted in 2015. The attitude and competence of healthcare providers to perform cervical spine reductions in district level hospitals, as well as the availability of resources, were assessed.

RESULTS: Availability of protocols improved by 20% from 2015 to 2023. Conversely, in 2023, 67% reported having no access to Cones calipers, compared to 58% in 2015. Most of the 2023 participants (74%) reported availability of imaging, while 46% and 51% of participants in 2015 and 2023, respectively, denied formal training in cervical reductions. There was a 51% reduction in practitioners who correctly identified the highest priority for closed reduction (worsening neurological deficit), from 2015 to 2023. Only 44% would attempt a reduction in the 2015 survey, and this declined to 21% in 2023. More practitioners considered reduction safe from 9% in 2015 to 21% in 2023. Most participants would change their practice given adequate training and resources.

CONCLUSION: The Western Cape public health sector remains ill-prepared for emergency reduction of cervical spine dislocations. There was no improvement in acute management of cervical spine injuries over the past decade, and the lack of resources, clinical skills and misperceptions around this are concerning and need addressing at provincial managerial level.

Level of evidence: 2

Keywords: cervical spine, cervical spine dislocation, spinal cord injury, spine trauma, closed reduction of cervical spine dislocation, district hospital

Introduction

Cervical spinal cord injuries (SCIs) are a common problem worldwide, accounting for 36% of all trauma cases.1 In South Africa (SA), most traumatic spinal injuries are caused by interpersonal violence and motor vehicle accidents (MVAs), with cervical dislocations being a common mechanism of injury.2,3

Cervical dislocations are potentially devastating, with high morbidity, if not managed promptly and appropriately.1,3-6 Additionally, the major demographic involved is that of young adult males, who are direct contributors to the South African economy.3-6 This loss of income, combined with cost of healthcare around SCIs, places an enormous burden on the fiscus.

Acutely, patients may present with neurogenic shock and autonomic disturbances which may be life threatening. Long-term sequelae, owing to permanent injury to the cord, include loss of motor (quadriplegia) and sensory function in relation to the anatomic level of injury. Higher injuries are associated with respiratory dysfunction. Patients with quadriplegia are usually fully dependent and may develop further complications due to immobilisation, reduced sphincter control and inability to effectively clear respiratory secretions.7

Cervical spine dislocations involve the primary injury (cord damage due to the traumatic insult), and the secondary injury (due to persistent cord compression and subsequent ischaemia). Current research into preventing secondary cord injury is ongoing, including cord resuscitation, medical management of inflammatory and haemodynamic processes, and early surgical timing.

Current literature increasingly shows early cord decompression improves outcomes.3,8 This is logistically difficult in resource-constrained environments, where the burden of trauma puts SCIs in direct competition with other life-threatening conditions. With limited access to theatre and scarcity of surgical skills, spinal decompression is often delayed, compromising spinal cord recovery.8

Cervical facet dislocations are the exception in this regard, as they can be managed emergently with closed reduction, allowing rapid neurological decompression. Closed reduction is safe and effective in 80% of patients, with an overall permanent neurological complication rate of < 1% and a transient neurological complication rate of up to 4%.7 Multiple studies favour early closed cervical reduction to maximise the chance of neurological recovery, and it is the recommended standard of care in these time-sensitive SCIs.9-14

Once reduced, the cord is effectively decompressed, and surgical stabilisation can then occur on the next available surgical list. Where local surgical skills are not available, the patient can be electively transferred to the appropriate hospital for definitive surgical stabilisation.

In South Africa, there exists a unique situation where in 2015, the apex court (Constitutional Court) ruled that cervical reduction should be achieved within four hours of the time of injury.15 This ruling was based on a study by Newton et al., who found that delays in reduction exceeding four hours had worse neurological outcomes.8 Newton et al. furthermore reported, that even with profound initial neurological motor deficit, early reduction within four hours could lead to dramatic motor functional improvement. These findings appear to be unique to cervical dislocations occurring during low-energy injuries (such as in sport) and cannot be extrapolated to high-energy dislocations or fracture dislocations, where the initial cord injury is likely to be irreversible.

Low-energy cervical dislocation is a true surgical emergency because of the potential for significant functional improvement with rapid spinal realignment. The Constitutional Court ruling has thus placed an additional burden on emergency care in the management of these injuries. To ensure compliance with best medical practice and optimise spinal injury care pathways, we undertook to review the available protocols, expertise and equipment available for emergency management of cervical dislocations in district hospitals in the Western Cape.

Furthermore, our objective was to determine whether the local management of these injuries had improved in the decade following the court ruling.

Methods

Primary- and secondary-level hospitals were identified in the Western Cape province of SA using the Western Cape public hospital listings. Superintendents and hospital managers were contacted, and permission was obtained to enrol medical staff in their respective emergency centres (which included consultants, registrars and medical officers). Identified staff members were invited to participate in the study, which consisted of an information sheet, consent form and a link to the Google Forms email-based survey tool. Ethical approval for the study was obtained.

Participants were questioned on their knowledge of cervical SCIs, skill with closed cervical reduction, the availability of protocols and resources in their facility for cervical SCIs, and their awareness of and familiarity with relevant protocols and resources. The results of this survey were retrospectively compared to a similar pilot survey by the University of Cape Town (UCT) Acute Spinal Cord Injury (ASCI) unit in 2015.14

The 2015 and 2023 surveys had similar questions but the 2015 survey interrogated radiography availability and equipment combined instead of separately. Basic demographic information included sex, age, qualifications, university of training, and current hospital of employment.

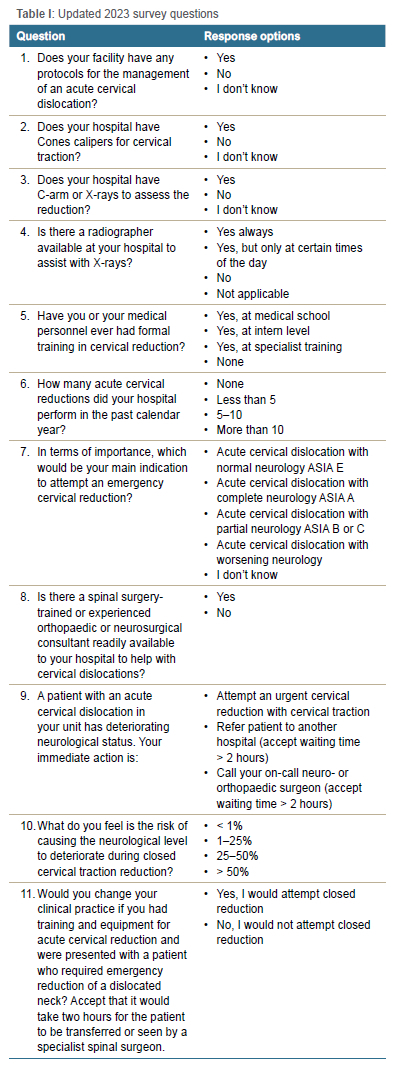

The questions for the updated (2023) survey are shown in Table I.

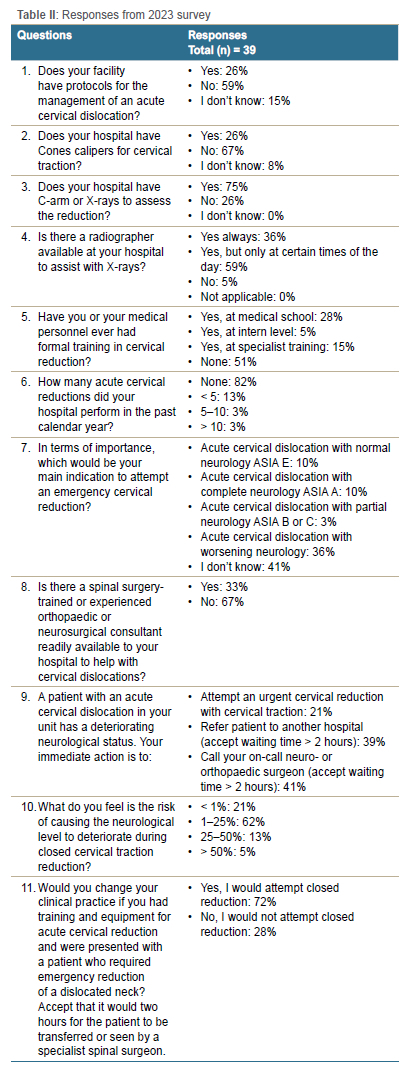

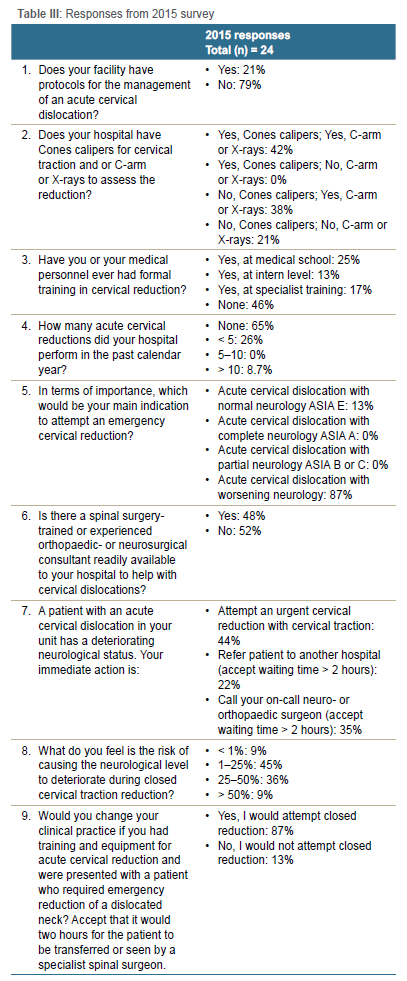

Both surveys were conducted with prior informed consent of the participants. The privacy of the participants was respected by utilising a survey tool which allowed for anonymity (names and personal identifiers were not required). Participation was completely voluntary and no incentivisation was offered to participants. The responses were recorded and compared to identify differences from the baseline established by the survey in 2015. These results are represented in Tables II and III.

Results

The 2015 survey received a total of 24 responses from public hospitals. The 2023 survey received 39 responses from public hospitals. Of the level 2 hospitals in the Western Cape, 63% participated in the study.

In 2015, 79% of the participants stated that there were no protocols in place for acute cervical SCI management at their facility. This decreased to 59% in 2023, reporting no protocols in place; unfortunately, this still represented more than half of the facilities not having a protocol for emergent management of SCI.

In 2023, 67% reported having no access to Cones calipers in their facility. Most clinicians (74%) reported availability of X-rays and/or C-arm. Despite the majority having imaging available, only 36% had a readily available radiographer, 59% had a radiographer only at certain hours of the day, and a small remainder had no radiographer service (5%). The 2015 survey had combined the above enquiry and found 42% had access to both Cones calipers and radiography, 38% had X-rays but no Cones, and 21% had no access to either. In total, in 2015, 58% of doctors had no reduction equipment, which decreased to 67% in 2023.

Regarding formal training for closed cervical reduction, 46% of participants in 2015 reported having no training, which increased to 51% in 2023. This lack of training occurred despite closed cervical reduction being part of the undergraduate core curriculum at both the University of Cape Town and Stellenbosch University.

The majority performed no cervical reductions in the past calendar year - 65% and 82% in 2015 and 2023, respectively. However, this was an individual tally and not a facility audit of the number of cases.

In 2016, 87% of participants correctly identified that worsening neurology in the setting of an acute cervical dislocation was the highest priority in terms of closed reduction, which decreased to 36% in 2023.

In 2016, 48% reported they had access to a neuro- or orthopaedic surgeon if required, compared to 33% in 2023.

Given the scenario of a patient with cervical spine dislocation and worsening neurological function, 44% of the 2015 participants reported they would attempt a reduction, declining to only 21% in 2023. The second most selected option in both surveys was to refer to the on-call specialist, accepting a two-hour penalty for treatment.

Most participants stated that, with adequate training and access to appropriate equipment and resources, they would attempt a cervical reduction (87% and 72% in 2015 and 2023, respectively).

Discussion

Cervical SCI accounts for 53% of traumatic SCI in SA and is associated with significant loss of neurological function. This injury is frequently encountered in young males, who are often family breadwinners and important contributors to the economy.16 The treatment of SCI is highly costly in terms of healthcare resources, and evidence-based management is essential to optimise outcomes.

Early decompression and stabilisation in acute SCI results in better neurological outcomes, especially in the case of low-energy cervical dislocations.8 Low-energy cervical dislocations can be indirectly decompressed by closed reduction, which is the internationally recommended emergent management of these injuries. Closed reduction is cheap, effective and safe. Furthermore, it does not need a pre-reduction magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) test, making it eminently suitable for the district hospital environment.

Closed reduction is the recommended management of cervical dislocations by both Stellenbosch University and the University of Cape Town in the Western Cape, and is included as a core knowledge subject in the medical undergraduate programme. While this practice is well established in tertiary hospitals, the management of cervical dislocations at district hospital level is varied, and depends on local clinician and administration enthusiasm.

The World Health Organization (WHO) handbook, 'Surgical care at the district hospital', considers closed cervical spine reduction and skeletal traction as being within the scope of practice for emergency personnel at district hospital level.17

In the Western Cape, district hospital emergency rooms are mostly managed by family physicians, who actively discourage local reductions in favour of transferring patients to tertiary hospitals. This was highlighted in the 2021 Family Medicine Forum for the Western Cape Department of Health: 'We actively discourage the district from purchasing cones calipers and other equipment meant for relocation of neck dislocation, as this is not within the scope of practice, or expertise, of all members of the clinical team assigned to care for the patient.' 18 Additionally, emergency treatment delays are common due to emergency medical services resource limitations and the large distances involved with hospitals in rural South Africa. A retrospective review of reduction times in the Western Cape found the median time from injury to reduction was 26 hours, which is concerning when viewed against scientific recommendations for early reduction as well as the apex court ruling of four hours.17,19 To avoid unnecessary delays to reduction, current recommendations from both university hospitals in the Western Cape are for acute cervical dislocations to be reduced in rural district hospitals, and once reduced, to be transferred to regional tertiary hospitals for definitive surgical stabilisation.

It was found that 67% of hospitals did not have the required traction equipment for reduction, despite this being recommended by the WHO as essential equipment for the district hospital.17 Aside from difficulties in sourcing calipers, the variety of different hospital beds complicate the Swan-neck pulley attachments, and often there is no suitable way of connecting the equipment. Even when appropriate equipment is available, these are subject to damage from incorrect use, lack of maintenance and theft.

Most hospitals had X-ray facilities (74%) but of these, only 36% had radiographer availability. Radiographer shortages are, unfortunately, experienced countrywide and reflect the economic difficulties of the healthcare system.

A considerable number of participants in both surveys (46% in 2015, 51% in 2023) reported a lack of formal training to perform cervical reductions with skull traction. Although closed reduction theory is included in the undergraduate curriculum at medical schools, the practice of reduction is infrequent, and this survey suggests that medical student knowledge is not consistently retained by junior doctors. Supporting this, in 2023, less than half of the participants correctly identified deteriorating neurological function, in the setting of an acute cervical dislocation, as the priority in terms of emergency management.

Further knowledge deficits were highlighted, with the perception of closed cervical reduction being an unsafe procedure, and only 21% correctly understanding its safety profile.

Cervical reductions were infrequently performed by the participants. The majority (65% and 82% in 2015 and 2023, respectively) had not performed closed reductions; however, this does not necessarily imply they had not managed patients requiring cervical reductions. The number of cervical dislocations encountered remains unknown, since patients might have been transferred to other facilities after diagnosis. It is notable, however, that 18% of respondents had performed cervical reductions in 2023, which speaks to the importance of reduction skills for emergency room clinicians.

When faced with a patient clearly requiring urgent reduction, fewer clinicians would attempt reduction, with 80% preferring to refer on to other facilities and accepting a further two-hour delay in spinal realignment. This reflects a combination of lack of clinical knowledge and training, as well as hospital administrator unwillingness to support local reductions. A well-constructed hospital protocol would simplify the clinical decision making and fast track these time-sensitive injuries.

Most study participants (87% and 72% in 2015 and 2023, respectively) felt that, given adequate training and equipment, they would change their clinical practice and attempt cervical reduction.

The practice of closed reduction is safe, effective and cheap, yet this study identified deficiencies in readiness and urgency in management of cervical spine dislocations, below best medical practice recommendations. Since the initial survey in 2015, the failure of most hospitals to establish protocols suggests administrative indifference towards managing cervical dislocations.

Conclusions

This study found that district hospitals in South Africa's Western Cape are ill-equipped to handle acute cervical dislocations, contrary to established best practices favouring urgent closed reduction. This research underscores the need for regional standards, improved emergency response, ongoing training for emergency room clinicians, and administrative backing to bridge this gap and improve patient outcomes.

This study was limited by the slight differences between the questions of the two surveys which made direct comparison challenging in some aspects. The paucity of responses from public hospitals in both surveys also limited the external validity of the study. Nonetheless, the authors feel this is a representative snapshot of the practice of cervical traction in the Western Cape.

Ethics statement

The authors declare that this submission is in accordance with the principles laid down by the Responsible Research Publication Position Statements as developed at the 2nd World Conference on Research Integrity in Singapore, 2010.

Prior to commencement of the study ethical approval was obtained from the following ethical review board: Human Research Ethics Committee, Health Sciences Faculty, University of Cape Town (Reference number: HREC REF: 230/2014), and institutional approval from the Western Cape Department of Health.

Informed written consent was obtained from all participants for being included in the study. This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Declaration

The authors declare authorship of this article and that they have followed sound scientific research practice. This research is original and does not transgress plagiarism policies.

Author contributions

SP: first author with contribution to the study design, data analysis and manuscript preparation

BS: contribution to data collection and analysis

SvdM: contribution to data collection and analysis

JS: contribution to data collection and analysis

NK: senior and corresponding author with contribution to the study conceptualisation, design and manuscript preparation

ORCID

Parbhoo S https://orcld.org/0009-0006-4187-1533

Salence B https://orcld.org/0000-0001-6296-9915

Simpson J https://orcld.org/0009-0006-0661-8276

Van der Merwe S https://orcld.org/0009-0009-7370-7721

Kruger N https://orcld.org/0000-0002-8543-5745

References

1. Ghafoor AU, Martin TW, Gopalakrlshnan S, Viswamitra S. Caring for the patients with cervical spine injuries: what have we learned? J Clin Anesth. 2006 Jan;17(8):640-49. [ Links ]

2. Vasiliadis AV. Epidemiology map of traumatic spinal cord injuries: A global overview. Int J Caring Sci. 2012 Sept;5(3):335-47. [ Links ]

3. Fielingsdorf K, Dunn RN. Cervical spine injury outcome - a review of 101 cases treated in a tertiary referral unit. SAMJ. 2007;97(3): 203-20. [ Links ]

4. Frankel HI, Coll JR, Charlifue SW, et al. Long-term survival in spinal cord injury: a fifty-year investigation. Spinal Cord. 1998;36:247-56. [ Links ]

5. Gerhart KA. Spinal cord injury outcomes in a population-based sample. J Trauma. 1991;31:1529-35. [ Links ]

6. Vaccaro AR, Daugherty RJ, Sheehan TP, et al. Neurologic outcome of early versus late surgery for cervical spinal cord injury. Spine. 1997;22:2609-13. [ Links ]

7. Hadley MN, Walters BC, Grabb BC, et al. Initial closed reduction of cervical spine fracture-dislocation injuries. Neurosurgery. 2002;50(3 Suppl):S44-50. [ Links ]

8. Newton D, England M, Doll H, Gardner BP. The case for early treatment of dislocations of the cervical spine with cord involvement sustained playing rugby. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93-B(12):1646-52. [ Links ]

9. Walters BC, Hadley NM, Hurlbert RJ, et al. Guidelines for the management of acute cervical spine and spinal cord injuries. Neurosurgery. 2013;60(CN Suppl 1):82-91. [ Links ]

10. Rathore FA. Spinal cord injuries in the developing world. International Encyclopedia of Rehabilitation. 2013; Centre for International Rehabilitation Research Information and Exchange (CIRRIE) Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51997860_Spinal_CordJnjuries_in_the_Developing_World [ Links ]

11. Como JJ, Diaz JJ, Dunham M, et al. Practice management guidelines for identification of cervical spine injuries following trauma: update from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma Practice Management Guidelines Committee. J Trauma. 2009;67:651-59. [ Links ]

12. Pimentel L, Diegelmann L. Evaluation and management of acute cervical spine trauma. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2010;28:719-38. [ Links ]

13. Hagen EM, Rekand T, Gilhus NE, Grönnlng M. Traumatic spinal cord Injuries- Incidence, mechanisms and course. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen. 2012;132(3):831-37. [ Links ]

14. Podium Presentation: NA Kruger. 1995, 01 September: Survey of the management of acute cervical spine dislocations with closed traction reduction in the Western Cape, 61st Congress of the South African Orthopaedic Association. [ Links ]

15. Oppelt v Head: Health, Department of Health Provincial Administration: Western Cape (CCT185/14) (2015) ZACC 33; 2016 (1) SA 325 (CC); 2015 (12) BCLR 1471 (CC) (14 October 2015). [ Links ]

16. Joseph C, Delcarme A, Vlok I, et al. Incidence and aetiology of traumatic spinal cord injury in Cape Town, South Africa: a prospective, population-based study. Spinal Cord. 2015;53(9):692-96. [ Links ]

17. World Health Organization. 2003. Surgical Care at the District Hospital. Retrieved from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/42564/9241545755.pdf?sequence=1 [ Links ]

18. Gunst C. Submission to clarify and improve management of spinal cord injuries at district hospitals: Family Medicine Forum: Rural Health Services. Western Cape Department of Health and Wellness. 2021. [ Links ]

19. Potgieter M, Badenhorst DH, Mohideen M, Davis JH. Closed traction reduction of cervical spine facet dislocations: Compelled by law. SAMJ. 2019;109(11):854-58. [ Links ]

Received: May 2024

Accepted: November 2024

Published: May 2025

* Corresponding author: nicholas.kruger@uct.ac.za

Editor: Dr Alberto Puddu, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

Funding: No funding was received for this study.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest that are directly or indirectly related to the research.