Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Contemporary Management

On-line version ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.17 n.2 Meyerton 2020

https://doi.org/10.35683/jcm19115.88

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Persuasive Influencers and the Millennials: How their relationships affect brand, value, and relationship equities, and customers' intention to purchase

FM MgibaI, *; N NyamandeII

IUniversity of the Witwatersrand, School of Business Sciences, Marketing division Freddy.mgiba@wits.ac.za ORCID NR: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4648-3218?lang=en

IIUniversity of the Witwatersrand, School of Business Sciences, Marketing division nomsi.nyams@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Influencer marketing has evolved into a trend within marketing, and is increasingly receiving well-deserved attention. Academic literature has documented the benefits of influencer marketing, however, its' impact on Brand equity, relationship equity, value equity, and the intention to purchase brands has not received much attention, especially within the African context. The purpose of this article is to explore how a persuasive influencer's message affects the millennials, via its' impact on the above-mentioned variables. The research followed a quantitative approach and used convenience sampling for data gathering. Data analysis was carried out by the use of Structural equation modelling with the aid of AMOS 25 statistical software. The study finds that there is a positive relationship between a persuasive influencer and brand, relationship, and value equities, and the intention to purchase from brands. It makes a unique contribution to academic theory building by providing another possible configuration of these variables. The resultant framework creates a space for future research on the use of both technology and celebrities. The study findings also have practical implications for managers who contemplate using social media influencers. It also sheds light for strategic managers who make decisions on online marketing budgets to target millennials.

Key phrases: Brand equity; influencer marketing; intention to purchase; relationship equity and value equity

1. INTRODUCTION

The proliferation of social media platforms available to citizens, and the continued rise of internet users have significantly changed the way individuals search, evaluate, rank, buy and consume products and services (Buhalis & Law 2008; Hudson & Thal 2013). This has significantly affected peoples' everyday lives (Rapetti & Cantoni 2013), and real-time information exchange has become an essential aspect of consumer behaviour (Hennig-Thurau, Marchand & Marx 2009). The new era has led to the emergence of both digital (Almeida 2019), and influencer marketing as major research topics (Lagrée, Cappé, Cautis & Maniu 2018). Influencer marketing came about as the result of the increased use of online celebrities (Guerreiro, Viegas & Guerreiro 2019), also called influencer marketers (Ranga & Sharma 2014). The internet provides new channels to disseminate opinions, reaching a greater number of people than traditional word-of-mouth (Mir-Bernal 2014). Digital Influencers can shape the behaviours and attitudes of consumers who tend to be loyal to them (Guerreiro, Viegas & Guerreiro 2019; Magno, Cassia & Ugolini 2018; Sahelices-Pinto & Rodríguez-Santos 2014). The major target market for influencers is the millennials (Dias 2003; Pophal 2016; SanMiguel, Guercini & Sádaba 2018; Smith 2011; Smith 2012). Authors give different periods of the births of millennials. For example, they are seen as people that were born between 1999 and 2002 (Blair 2017), 1980 and 1990 (Stein 2013), and 1976 and 2001 (Brack 2014). It is generally accepted that these people were born during the time of rapid internet and technology growth (Blair 2017). It is the first generation to grow up surrounded by digital media, people who consider computers and mobile phones to be essential tools for many activities (SanMiguel et al. 2018), who are accustomed of buying and socialising online (Reeves & Oh 2007; SanMiguel et al. 2018; Smith 2011). This generation has been denominated in multiple ways: Digital Natives; Gen.com; Generation Next; Generation Tech; Generation Why; Generation Y; Generation 2000; Instant-Message Generation (Cantoni & Tardini 2010; Rapetti & Cantoni 2013). This market segment is presently not fully understood by organisations (Heinzerling 2018). The relevance of this study lies in the fact that this generation is growing in numbers (Moos, Pfeiffer & Vinodrai 2017). Their habits, purchasing, and consumption behaviours are also changing (Castellini & Samoggia 2018; Gentilviso & Aikat 2019). Brack (2014) further states that the best way to influence this generation is through networks, and communities. Organisations, therefore, need to adapt to this new market reality.

2. PROBLEM STATEMENT AND PURPOSE OF THE STUDY

Riedla and Von Luckwald (2019) state that more and more advertising spending is flowing into social media influencer marketing (SMIM). However, research on the effectiveness of SMIM is still relatively scant (Godey, Manthiou, Pederzoli, Rokka, Aiello, Donvito & Singh 2016; Haenlein and Kaplan 2010; Schaefer 2012), which give rise to a lack of understanding of its' contribution to organisational success (Konstantopoulou, Rizomyliotis, Konstantoulaki & Badahdah 2019). Other researchers that attempted to explain the success of celebrity influencers concentrated on the choice of social media platforms (Ismail 2017; Roy & Jain 2017). Consequently, existing literature pays insufficient attention to how the persuasiveness of an influencer affects customer equity (brand, value, and relationship equity) and customers' purchase intentions. In addition, none of these few pieces of research have covered the African context (Kim & Ko 2012; Yadav & Rahman 2018). This study responds to these knowledge gaps by empirically investigating the effectiveness of influencers on brand, value, and relationship equities, and, on consumers' purchase intentions. It aims to determine how influencer marketing contributes to social media marketing effectiveness by exploring consumers' responses to influencer social media posts within the South African context. This will be realised by measuring the persuasive influencer's effect on customer equity drivers; which are relationship equity, brand equity, value equity, and purchase intentions.

This study employs social learning, source attractiveness, and social influence theories as the theoretical foundations to develop the predicting relationships among these variables (relationship equity, brand equity, value equity, and purchase intentions). The interrelatedness of these theories is relatively unexplored in literature. Consequently, there is a lack of 'theoretification' and empirical validations of the relationships proposed in the resultant framework from this study. This research proposes a set of interconnected relationships between the above-mentioned variables in a single model using these three (3) theories. The proposed network of relationships between the variables derived from these theories adds another tool to aid the understanding of influencer marketing and the millennial market segment. The study, therefore, contributes to the building of literature that will authenticate the inclusion of influencer marketing strategies in organisations. It also extends knowledge of the effects of technology and online celebrities on organisations' customer-based equity drivers. For management practitioners, it will provide an additional tool to assist them with the choice of resources to use when deciding on marketing campaigns, which target this market segment. This new knowledge can also find practical applications in social media budget decisions, and in the choice of influencers within the African context.

3. LITERATURE REVIEW

This subsection contains three (3) grounding theories and the empirical literature review.

3.1 Grounding theories, the rationale for the choice

Bandura's social learning theory (SLT) deals with social learning and personality development (Kilinç, Yildiz & Harmanci 2018). It provides a theoretical framework of socialisation agents such as celebrities, family, or peers (North & Kotze 2001), and can be used to predict consumption behaviours (King & Multon 1996). This theory posits that an individual's intention to purchase products is highly influenced by the respondents' attitude and effectiveness of social media influencers (Lim, Radzol, Cheah & Wong 2017). In the process of shaping audience attitudes and decision making through social media, influencers can influence consumption behaviours (Makgosa 2010). According to SLT, an individual derives motivation and consequently exhibits favourable attitude from socialisation agents via either direct or indirect social interaction (Subramanian & Subramanian 1995).

Source attractiveness theory (SAT) takes a different angle to SLT. Source attractiveness refers to how much a follower identifies with the influencer, and recognises the source as a referent other (Schaefer 2012). Attractiveness is a function of likability (fondness for the influencer), familiarity (knowledge of them from past exposure or experience), and similarity (perceived resemblance between followers and influencers) (Martensen, Brockenhuus-Schack & Zahid 2018). There is a positive correlation between source attractiveness and consumer attitude as well as purchase intention (Petty, Cacioppo & Schumann 1983). McGuire (1985) noted that source attractiveness directly influences the effectiveness of an endorsement. Endorsers with attractive features are more inclined to capture followers' attention (Lim et al. 2017), drive the acceptance rate of advertising (Erdogan 1999), and can exert a positive attitude on consumers and subsequently, on their purchasing intention (Till & Busler 2000).

The last theory in aid of the understanding of how influencers affect consumers is Kelman's theory of social influence (Kelman 1958). This theory outlines the determinants and consequences of influence and distinguishes compliance, identification, and internalisation as the processes of influence. These three (3) processes differ in the level of public conformity and private acceptance (Kapitan & Silvera 2015). Compliance occurs when individuals accept influence to achieve a favourable reaction from other individuals, identification occurs when individuals accept influence to establish and/or maintain a satisfactory relationship/kinship with other individuals, and internalisation occurs when individuals accept influence because the underlying actions and ideas of the induced behaviour is fundamentally rewarding and aligns with their value system (Crano 2000; Kapitan & Sivera 2015). In addition to the advertised products or services supporting their values, consumers ultimately end up believing that it will also meet their needs and wants because of internalisation (Pitesa & Thau 2012; Tsai & Bagozzi 2014).

3.2 What influencer marketing entails

The basic assumption of influencer marketing is that online personalities shape consumers' attitudes through tweets, posts, blogs, or any other formats of communication on social media (Freberg, Graham, McGaughey & Freberg 2011). Influencers are brand advocates, experts, pioneers in their field, recognised by opinion leaders (Rinka & Pratt 2018), who characterise themselves as independent endorsers who shape audience attitudes through blogs, tweets, and the use of social networks through which they publish generated content (Magno et al. 2018; Sahelices-Pinto & Rodríguez-Santos 2014). Influencer marketing engages people to attract the attention of targeted audiences on digital platforms (Bognar, Puljic & Kadezabek 2019; Vered 2007), and to spread the message of a specific trend in the form of sponsored content (Sammis, Lincoln & Pomponi 2016). Some of the most notable characteristics of influencers that give them their capacity to influence are their credibility, social influence (Metzger & Flanagin 2013), and likability (Brodsky, Neal, Cramer & Ziemke 2009). Due to their capacity to influence people's perceptions and to make them do different things (Purwaningwulan, Suryana, Wahyudin & Dida 2018), marketers use them to leverage their relationship with their followers (Xiao, Wang & Chan-Olmsted 2018). Influencer marketing is closely related to Celebrity marketing, and their differences are only on the platforms used. Influencer marketing uses celebrities from the world of social media instead of the television and the press media normally associated with celebrity marketing (Sammis et al. 2016). For companies that are targeting younger generations, social network influencers are more trustworthy (Lim et al. 2017). This study proposes that persuasive influencers positively impact customer equity and maximises organisations' long-term performance (Vogel, Evanschitzky & Ramaseshan 2008). This in turn, can be achieved via their effect on the four (4) drivers to customer equity, namely: intention to purchase, brand equity, relationship equity, and value equity (Cheng, Tung, Yang & Chiang 2019; Rienetta, Hati & Gayatri 2017).

3.3 A persuasive influencer and the message source

For the influencer to be useful to any marketing programme, he/she must be able to persuade people to adopt an attitude or to take the desired action. Many studies have suggested different ways to persuading people to one's viewpoint. Persuasiveness is a function of the level of expertise of the message sender (Kumar & Mirchandani 2012; Martensen et al. 2018), the senders' attractiveness to their followers (Schaefer 2012), the number of followers (Djafarova & Rushworth 2017), and the characteristics of the influencer (Seiler & Kucza 2017). The source of the message communicated also matters in influencer marketing.

The Firm-generated content (FGC) message is a media marketing message curated, published and controlled by firms (Konstantopoulou et al. 2019). Technology has however increased the opportunities for users to generate and spread brand messages, which can also affect the perceptions of consumers and potential consumers. User-generated message (UGC) is social media communication created and controlled by users that firms can only influence but never directly control (Konstantopoulou et al. 2019). It is known that UGC has a positive influence on the perceived quality of the message communicated (Simon 2016). Organisations can harness the power of persuasive influencers by taking advantage of the differences between FGC and UGC. One of the best assets that influencers possess is their persuasive communication, which they can use to influences their audiences' beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviours (Nojavanasghari, Gopinath, Koushik, Baltrusaitis & Morency 2016).

3.4 Influencer persuasiveness and brand equity

Brand equity aids brand extensions, and brand strength (Kotler & Keller 2009). Brand equity is a customer's fit with the brand (Razzaq, Yousaf & Hong 2017), after his/her subjective evaluation (Zhang, Ko & Kim 2012). Brand equity increase customer loyalty's intentions (Razzaq et al. 2017), which can lead to increased company market value (Alkaya & Taşkın 2017), and the improvement in the product or service information consumers communicate through the internet (Djafarova & Rushworth 2017; Razzaq et al. 2017). Kelman's theory of social influence deals with how influence happens, in terms of compliance, identification, and internalisation of that influence (Crano 2000; Kapitan & Sivera 2015; Kelman 1958). It also concludes that the 'influenced' are likely to imitate influencers they perceive to be credible (), and trustworthy (Liljander, Gummerus & Söderlund 2015; Magno et al. 2018; Rieh & Danielson 2008). Potential consumers are likely to trust messages shared by influencers on social networks (Magno et al. 2018). The influencer's message usually appears to be a UGC, which can positively influence brand loyalty (Shen & Bissell 2013). In light of the nature of an influencer and the discussion on brand equity, the following hypothesis is proposed:

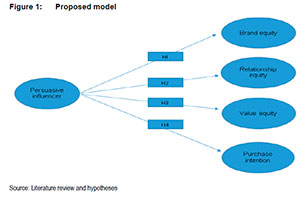

H1: There is a positive relationship between the influencer's persuasiveness and brand equity.

3.5 Influencer persuasiveness and value equity

Quality, cost, and accessibility of products and services influence value equity (Lemon, Rust & Zeithaml 2001). It is derived from the benefits consumers receive from purchases when compared to the price of the product (Razzaq et al. 2017). Value equity, therefore, forms the base of any company's relationship with the customer for long-term survival (Kim et al. 2010; Lemon et al. 2001). It was indicated above that influencers are perceived to be credible (Liljander et al. 2015; Metzger & Flanagin 2013), knowledgeable, and respected individuals (Bognar et al. 2019), and that their messages appear to be UGC. A User-generated message helps with Influencer messages' persuasive power (Huang, Burtch, Gu, Hong, Liang, Wang, Fu & Yange 2019). Influencers' postings on social media are likely to influence the cost-benefit evaluation of any potential customer. The theory of social influence also deals with people's desire to comply, identify and internalise behaviours recommended by influencers (Crano 2000; Kelman 1958). Lastly, it is generally accepted that customers referred by influencers bring more revenue, and are more profitable (Palmatier, Kumar & Harmeling 2017; Van den Bulte, Bayer, Skiera & Schmitt 2018). It can, therefore, be hypothesised that:

H2: Influencer persuasiveness has a positive effect on value equity.

3.6 Influencer persuasiveness and relationship equity

Relationship equity (RE) covers equity from the perspective of customers. It is the outcome of their value perceptions judgment in relation to the costs involved (Yu & Yuan 2019). Relationship equity can ultimately result in customer loyalty beyond their subjective evaluations of a brand (Kim et al. 2010; Lemon et al. 2001). It is a useful tool to create and sustain the relationship between a customer and an organisation (Zeithaml, Bitner & Gremler 2006). Relationship equity acts as the "glue" between customers and the brand and it makes the customer continue purchasing the same brand (Rust & Verhoef 2005). If a customer feels well treated, relationship equity is said to be high (Kristof, Odekerken-Schröder & lacobucci 2001).

Another name for relationship equity is intention equity (González-Benito, Martos-Partal & Fustinoni-Venturini 2015). In today's world, RE is also a function of social media communication (Hutagalung & Situmorang 2018). Kim and Ko (2012) state that social media marketing activities create purchase intention and loyalty to a brand. Relationship equity can result from the linking of customers to a larger like-minded virtual community (Lemon et al. 2001). Brands can therefore use persuasive influencers to form relationships with customers (Booth & Matic 2011), because influencers are perceived to be relatable, reliable, and are important messengers for consumers looking for recommendations (Forbes 2016). Persuasive influencers can alter the perception of their audience via their social influence (Gonzalez et al. 2015). Their message is likely to be more credible and influential because it can be perceived as an on-going communication emanating from the end-user of the brand (Eccleston & Griseri 2008; Liu-Thompkins & Rogerson 2012). These customer perceptions can improve both the trustworthiness and credibility of the message (Cheung & Thadani 2012). Persuasive influencers can cause customers to stick with a brand and to recommend it to others (Barreto 2020).

Another source of strength for influencers is their attractiveness to their audience. Source attractiveness theory states that there is a positive correlation between source attractiveness and consumer's attitude. Attractive influencers are more likely to capture followers' attentions (Lim et al. 2017), and increase the acceptance rate of the information they are communicating (Erdogan 1999). Consumers end up identifying with the source, and the source's appearance affects their fondness for the influencer (Martensen et al. 2018). Pangaribuan, Ravenia and Sitinjak (2019) state that opinions from people in the same social network are highly valued by consumers in that network. Gleaning from the argument above, it can be hypothesised that:

H3: A persuasive influencer has a positive effect on relationship equity

3.7 Influencer persuasiveness and purchase intention

As consumers are becoming more reliant on social media for information searches related to purchases, firms now understand that providing online content affects customers' purchase intentions (Konstantopoulou et al. 2019). Alkaya and Taşkın (2017) define purchase intention as the possibility of a customer to buy a product or service based on their perceptions, attitudes, and satisfaction. Since purchase intention measures the future contribution of customers to the brand and might result in sales (Alkaya & Taşkın 2017; Kim & Ko 2012), it can be used to forecast customers' actions (Morwitz 2014; Wong 2019). In general, the intention to purchase a brand is formed after customers have evaluated the product or service (Harker, Brennan, Kotler & Armstrong 2015; Spears & Singh 2004), in terms of quality, satisfaction, and the expected switching costs (Weisberg, Te'eni & Arman 2011). Influencer marketing focuses on identifying individuals who have expertise in the subject matter and are capable of reaching and influencing specific targets of potential buyers because of their relationships with their followers. Source attractiveness theory states that endorsers with attractive features can exert a positive attitude on consumers and subsequently, on their purchasing intention (Till & Busler 2000). Social learning theory states that people's consumption behaviour is dependent on social agents (Makgosa 2010; North & Kotze 2001), or social media influencers (Lim et al. 2017). Persuasive social media influencers can easily generate and spread trends and opinions about brands (Zhang, Zhao & Xu 2016). Millennials are heavy users of social media (Chatzigeorgiou 2017).

H4: Influencer persuasiveness has a positive effect on potential customers to purchase a brand.

For the diagrammatic representation of the relationships proposed in the hypotheses, see Figure 1 below.

4. METHODOLOGY AND DATA ANALYSIS

The study explored relationships between variables and followed a quantitative positivist approach as per scholarly recommendations (Kivunja & Kuyini 2017). When using this approach, a researcher can quickly administer, analyse, and interpret the results (McKenzie 2013). The university segment in Gauteng provided the research sample for this study (Diggines & Wiid 2015; Taherdoost 2016). The research targeted the millennials (age group 19-35), as they are assumed to be extensive social media users, and acceptors of social meanings from influencers (Chatzigeorgiou 2017). This group is also most likely to have exposure to both brands and influencer social media. This is in line with other studies that concentrated on either influencer marketing or the use of social media (Duffet 2017; Yadav & Rahman 2018). Convenience sampling was followed for data collection (Cant, Gerber-Nel, Nel & Kotze 2005; Diggines & Wiid 2015; Kumar 2011; Taherdoost 2016). After obtaining permission from lecturers, the researcher distributed the self-administered questionnaires to all the students in the targeted classes. The use of self-administered questionnaires for primary data gathering was motivated by the accuracy, low-cost nature, and the effectiveness of this method (Cant et al. 2005).

4.1 Research instrument

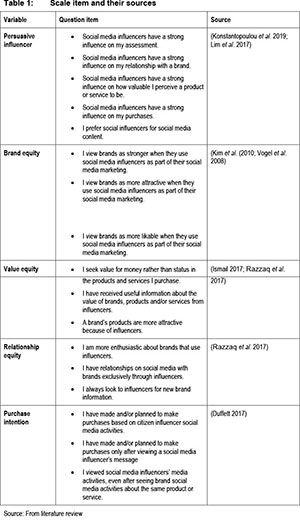

The survey instrument was built based on prior research and used a Likert-type scale with response options ranging from 1=Strongly disagree to 5=Strongly agree. The questionnaire development was in English and the need for translation did not arise (Dao, Le, Cheng & Chen 2014), as all the targeted participants were English literate. Each construct utilised multiple item measures to avoid measurement errors related to the unreliability of single measures (Gliem & Gliem 2003). Most of the scale items were adapted from previous studies to fit the current context. For each of the constructs and scale item sources, see Table 1 below. Taking into account the analysis method used (structural equation modelling); the sample size of 350 was deemed sufficient (Wolf, Harrington, Clark & Miller 2013).

To address ethical concerns, participants were informed about the purpose of the study (Nunan & DiDomenico 2013), before their responses were recorded (Hegney & Chan 2010). In addition, their responses were all coded to protect their anonymity. Lastly, privacy and confidentiality are other issues considered following the country's laws (South Africa 2008), and academic protocol requirements (Boyd 2010; Walls, Parahoo, Fleming & McCaughan 2010). Before any data gathering could commence, ethical clearance was obtained from the concerned institution. The protocol number is CBUSE/1476.

4.2 Data analysis

The descriptive statistics results are given in Table 2.

From the Table 2, it is apparent that 62% of the willing participants were female while 37% of participants were male and 1% preferred to not specify their gender. Females made up most of the sample. About 76% of participants were in the range of 18-23 years old, which was expected, as all the participants were university students. Instagram was the most preferred/used social media platform with 46% of participants indicating it was their platform of choice, followed by Twitter at 23%. The daily social media usage was evenly split as the figures in the table. About 21% of participants used social media for between 0 and 1 hour per day. Participants who use social media for 1-2 hours and more than 3 hours a day both account for 26% of the sample respectively. Participants with daily usage of 2-3 hours represented 27% of the sample. On the choice of the content recommending brands, about 70% of participants preferred influencer generated content with only 30% preferring brandgenerated content.

4.3 Data accuracy results

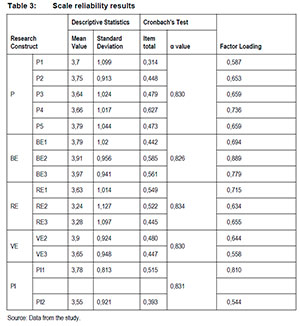

Cronbach Alpha coefficients were used for reliability checking (Larwin & Harvey 2012). A figure of 0.7 or higher is acceptable. Reading from Table 3 below, all Cronbach Alpha values were above 0.8, and scale reliability was therefore confirmed.

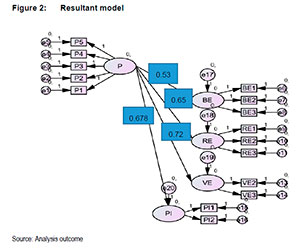

According to Schimmack (2019), construct validation requires the demonstration of both convergent and discriminatory validity. Convergent validity assesses the level of correlations of multiple indicators of the same construct (Sarstedt, Ringle, Smith, Reams & Hair 2014), and thus ensure that concepts that should be related are indeed related (Zikmund, Babin, Carr & Griffin 2010). To establish it, the researchers followed the scholarly recommended approach of using both the composite reliability (CR), and the average variance extracted (AVE) values. Their cut-off values are >0.6, and >.5 respectively (Wang, Cheng, Purwanto & Erimurti 2011), For AVE, the formula AVE=Σκ2 / n, where K represents the factor loadings of the indicators, and n, the number of items measuring the construct (Ahmad, Zulkurnain & Khairushalimi 2016; Ab Hamid, Sami & Sidek 2017). All the AVE values were acceptable as they ranged between 0.5 and .63. The formula for calculating the CR is CR= Σκ2 / κ2 + [1- κ2] (Ahmad et al. 2016). All scale items exceeded the threshold values, except VE1, which loaded weakly (below 0.3), prompting its' removal for further analysis. The final model is displayed in Figure 2 below.

The assessment of discriminant validity (DV) is of utmost importance in research that involves latent variables along with the use of several items or indicators for representing the construct (Ab Hamid et al. 2017). DV measures the extent to which the constructs are empirically distinct from each other in the structural model. Two (2) approaches are generally applicable in marketing research studies. The average value extracted (AVE), and the inter-correlation matrix approach. Recent studies however have shown that AVE assessments are no longer suitable for discriminant validity checks (Hair, Risher, Sarstedt & Ringle 2019; Henseler, Ringle & Sarstedt 2015).

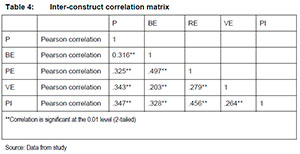

Taking the above into consideration, DV for the present study was confirmed using the inter-construct correlation matrix as recommended by many other scholars (Morar, Venter de Villiers & Chuchu 2015; Van Mierlo, Vermunt & Rutte 2009; Shaffer, De Geest & Li 2016). ln this approach, the higher the correlation between the constructs, the lower the discriminant validity of the variables (Nunnally & Bernstein 1994). Different scholars recommend different cut-off values. According to Chinomona, Lin, Wang and Cheng (2010), the inter-correlations for all paired latent variables should be less than one. Nunnally and Bernstein (1994) recommend a threshold value of 0.7, and Kenny (2019) a value of 0.85. Table 4 below, shows the inter-correlation values for all paired latent variables and they all range between 0.497 and 0.203. Discriminant validity was therefore confirmed.

To address these concerns, many scholars recommend that no decision concerning the goodness of fit should be based on a single index, no matter how favourable to the model that index might appear (Gullen 2001; Hooper, Coughlan & Mullen 2008; Raykov & Marcoulides 2012; Tomarken & Waller 2005). For that reason, GOF should be assessed using a variety of indices (McNeish 2018; Yuan et al. 2016). As shown above, the use of indices brings into sharp focus the problem of deciding on the cut off values. Scholars do not agree on these values as well (Greiff & Heene 2017; Saris, Satorra & Van der Veld 2009). Given the above into account, the researchers used the pragmatic approach of using five commonly used fit indices (Byrne 2012; Kline 2015), which are Chi-Square test, CFI, GFI, TLI, and RMSEA (Miyejav 2017; Shi et al. 2019). Table 5 displays all the fitness indices obtained, together with some sources of their threshold values. According to Chang and Chen (2009), the CFA results indicate a promising and acceptable overall model fit. Given the above, the present researchers accepted the values shown in Table 5 as the basis for accepting the model fitness test.

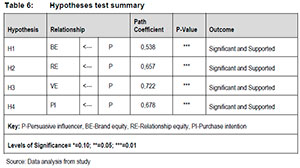

After confirming the acceptability of the CFA measurement model fit, the study proceeded to the hypothesis testing using SEM with the AMOS 25 software package, the results of which are given in Table 6 below.

5. SUMMARY OF THE HYPOTHESES TESTING

As seen from the results from Table 6, influencers positively influence a firm's: brand equity, relationship equity, value equity, and the intention of customers to purchase a brand's offer through their social media activities. The effect, of the persuasive influencer on these different forms of customer equities is not in equal measure. For instance, the influencer's impact on value equity is much more than its' impact on brand equity as evidenced by the path coefficients 0.722 and 0.538 respectively. Given a choice of which customer equity managers should concentrate on influencing, it makes sense to target these different forms in order of value equity, purchase intention, relationship equity, and lastly, on brand equity.

5.1 Discussion of the hypotheses results

The current influencer marketing strategy is a "one-size-fits-all" approach and leaves other potential areas that deserve attention (Hughes, Swaminathan & Brooks 2019). The present study adds to the growing literature on the effectiveness of influencer marketing on brand equity, value equity, relationship equity, and the intention to purchase from brands. It has shown that; persuasive influencer social media marketing activities have a positive effect on brand equity; persuasive influencer social media marketing activities have a positive effect on relationship equity; persuasive influencer social media marketing activities have a positive effect on value equity; and that, persuasive influencer social media marketing activities have a positive effect on purchase intention. This is in line with other researchers' findings. How messages are communicated to the intended audience is a factor in any context (Kimpakorn & Tocquer 2010). For instance, Luxton, Reid and Mavondo (2017) found a close relationship between organisational communication and its' brand equity. Influencers provide opportunities for viral growth and thus increase the customer-based brand equity (De Veirman, Cauberghe & Hudders 2017; Rosario, Sotgiu, Valck & Bijmolt 2016). Knoll (2016) also showed that influencer marketing is very useful for relationship equity creation. Influencer marketing can also generate viral e-word of mouth (Ewom), which can be a big asset to improve a company's valuation. Social media influencers have a place in marketing practice because when customers choose products, they normally go for the one recommended by influencers.

5.2 Management implication of the study

It is indispensable to understand how influencer marketing impacts organisational value, and this value is largely determined by its' customer-based equity. All customer experiences should be carefully managed (El Naggar & Bendary 2017), including via advertisements and promotional messages. The present study supplies some of the tools for achieving that. It provides the first empirical evidence of the effectiveness of influencers in terms of highlighting the aspects that they affect the most in customer value. By using three (3) grounding theories, it also supplies a novel theory-informed research framework to management scholars. In this study, the different forms of customer equity and the intention to purchase were determined using multiple indicators. The findings will generate interest for further research to identify which of those indicators organisations can concentrate resources allocation on. In light of the findings of this research, it makes sense for management practitioners to solicit influencers to post about products and brands, as these positively affect customers' perceptions and their buying decisions. The intent of their influencer campaign should determine the choice of both media and influencers, because, the influencers do not affect the different dependent variables in the same measure. In conclusion, the findings of this study can aid investment decisions for organisational growth, and customer intelligence gathering (because of the interactive nature of influencer-customer communication). The findings should go a long way in highlighting areas of organisational resources planning, in light of the advancement in technological development.

5.3 Limitations of the study

The participants for the study were university students. The outcomes of the research cannot, therefore, be expected to produce immediate practical benefits to organisations. The benefits can only be realised in the long-term. The choice of participants also limits the generalisability of the outcomes. The student population does not accurately represent the entire South African population. Lastly, the study does not deal with some of the negative sides of influencer marketing, such as potential influencers inflating the size of their following and possible influencer fraud in general.

REFERENCES

AB HAMID MR, SAMI W & SIDEK MH. 2017. Discriminant Validity Assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT Criterion. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 890(1):1-5. [Internet:https://iopscience.iop.org/issue/1742-6596/890/1; downloaded on 27 July 2020. [ Links ]]

AHMAD S, ZULKURNAIN NNA & KHAIRUSHALIMI FI. 2016. Assessing the Validity and Reliability of a Measurement Model in Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). British Journal of Mathematics & Computer Science 15(3):1-8. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.9734/BJMCS/2016/25183. [ Links ])

ALKAYA A & TAS.KIN E. 2017. The Impact of Social Media Pages on Customer Equity and Purchase Intention: An Empirical Study of Mobile Operators. Journal of Business Research - Turk 3:122-133. (DOI:10.20491/isarder.2017.291. [ Links ])

ALMEIDA MN-d. 2019. Influencer marketing on Instagram: how influencer type and perceived risk impact choices in the beauty industry. (Dissertation, NOVA information management school). [Internet:http://hdl.handle.net/10362/71585; downloaded on 27 July 2020. [ Links ]]

BARRETO AM. 2020. Measuring Brand Equity with Social Media. Prisma Social: revista de investigación social 74-85. [Internet:https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7263738; downloaded on 27 July 2020. [ Links ]]

BLAIR O. 2017. WHAT COMES AFTER MILLENIALS? MEET THE GENERATION KNOWN AS THE 'LINKSTERS'. Independent. [Internet:https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/millennials-generation-z-linksters-what-next-generation-x-baby-boomers-internet-social-media-a7677001.html; downloaded on 27 July 2020. [ Links ]]

BOGNAR ZB, PULJIC NP & KADEZABEK D. 2019. Impact of influencer marketing on consumer behavior. Economic and Social Development: Book proceedings, 301-309. [Internet:https://search.proquest.com/openview/0ae451357e462549c9f66b2a36dff6a7/1.pdf?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2033472; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

BOOTH N & MATIC JA. 2011. Mapping and leveraging influencers in social media to shape corporate brand perceptions. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 16(3):184-191. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/13563281111156853. [ Links ])

BOYD D. 2010. Privacy and Publicity in the Context of Big Data. WWW conference, Raleigh, North Carolina. . [Internet:http://www.danah.org/papers/talks/2010/WWW2010.html; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

BRACK J. 2014. Maximizing Millennials in the Workplace. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, Keenan- Flagler Business School, UNC Executive Development. White paper: [Internet:http://execdev.kenan-flagler.unc.edu/blog/maximizing-millennials-in-the-workplace; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

BRODSKY SL, NEAL TMS, CRAMER RJ & ZIEMKE MH. 2009. Credibility in the Courtroom: How Likable Should an Expert Witness Be? Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 37(4):525-532. [Internet:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20019000; downloaded on 27 July 2020. [ Links ]]

BUHALIS D & LAW R. 2008. Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the internet: The state of eTourism research. Tourism Management 29(4):609-623. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.01.005. [ Links ])

BYRNE BM. 2012. A primer of LISREL: Basic Applications and Programming for Confirmatory Factor Analytic Models. Springer Science & Business Media. Marketing Research. Claremont: New Africa Books (Pty) Ltd. [Internet:https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9781461388876; downloaded 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

CANT M, GERBER-NEL C, NEL D & KOTZE T. 2005. Marketing Research. Van Schaik, South Africa. [Internet:https://www.vanschaiknet.com/book/view/188; downloaded 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

CANTONI L & TARDINI S. 2010. The Internet and the Web. In Albertazzi D & Cobley P. Eds. The media. An introduction. 3rd ed. Longman. New York.[Internet:https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=CANTONI+L+%26+TARDIN I+S.+2010.+The+Internet+and+the+Web.&btnG=; downloaded on 28 July 2020. [ Links ]]

CASTELLINI A & SAMOGGIA A. 2018. Millennial consumers' wine consumption and purchasing habits and attitude towards wine innovation. Wine Economics and Policy 7(2):128-139. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wep.2018.11.001. [ Links ])

CHANG HH & CHEN SW. 2009. Consumer perception of interface quality, security, and loyalty in electronic commerce. Information & Management 46(7):411-417. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2009.08.002. [ Links ])

CHATZIGEORGIOU C. 2017. Modeling the impact of social media influencers on behavioral intentions of millennials: The case of tourism in rural areas in Greece. Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing 3(2):25-29. [Internet:https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/67069; downloaded 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

CHENG YY, TUNG WF, YANG MH & CHIANG CT. 2019. Linking relationship equity to brand resonance in a social networking brand community. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 35:1-9. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2019.100849. [ Links ])

CHEUNG CMK & THADANI DR. 2012. The impact of electronic word-of-mouth communication: A literature analysis and integrative model. Decision Support Systems 54(1):461-470. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2012.06.008. [ Links ])

CHINOMONA R, LIN JYC, WANG MCH & CHENG JMS. 2010. Soft Power and Desirable Relationship Outcomes: The Case of Zimbabwean Distribution Channels. Journal of African Business 11(2):182-200. [Internet:https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15228916.2010.508997;; downloaded on 27 July 2020. [ Links ]]

HOOPER D, COUGHLAN J, & MULLEN MR. 2008. Structural Equation Modelling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6(1):53-60. [Internet:http://mural.maynoothuniversity.ie/6596/; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

CRANO WD. 2000. Milestones in the Psychological Analysis of Social Influence. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice 4(1):68-80. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.4.1.68. [ Links ])

DAO WV-T, LE ANH, CHENG JM-S & CHEN DC. 2014. Social media advertising value: The case of transitional economies in Southeast Asia. International Journal of Advertising 33(2):271-294. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.2501/IJA-33-2-271-294. [ Links ])

DE VEIRMAN M, CAUBERGHE V & HUDDERS L. 2017. Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising 36(5):798-828. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2017.1348035. [ Links ])

DENIZ ME, TEKIN EG & SATICI B. 2019. Guilt and School Satisfaction among Turkish Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Self-esteem. Turkish Psychological Counselling and Guidance Journal 9(53):547-563. [Internet:https://avesis.yildiz.edu.tr/yayin/4a3c67f0-7862-447e-98a2-4df14e4c9ae4/guilt-and-school-satisfaction-among-turkish-adolescents-the-mediating-role-of-self-esteem; downloaded on 29 July 2020. [ Links ]]

DIAS LP. 2003. Generational buying motivations for fashion. Journal of fashion marketing management 7(1):78-86. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/13612020310464386. [ Links ])

DIGGINES C & WIID J. 2015. Marketing Research, 3rd edition. Juta and Company Ltd. Cape Town. [Internet:https://www.loot.co.za/product/jan-wiid-marketing-research/nkvt-3483-g060; downloaded on 27 July 2020. [ Links ]]

DJAFAROVA E & RUSHWORTH C. 2017. Exploring the credibility of online celebrities' Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Computers in Human Behaviour 68:1-7. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.009. [ Links ])

DUFFETT RG. 2017. Influence of social media marketing communications on young consumers' attitudes. Young Consumers 18(1):19-39. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-07-2016-00622. [ Links ])

ECCLESTON D & GRISERI L. 2008. How does web 2.0 Stretch Traditional Influencing Patterns? International Journal of Market Research 50(5):591-616. (DOI: https://doi.org/10.2501%2FS1470785308200055. [ Links ])

EL NAGGAR RAA & BENDARY N. 2017. Impact of Experience and Brand trust on Brand loyalty, while considering the mediating effect of Brand equity dimensions, an empirical study on mobile operator subscribers in Egypt. The Business and Management Review 9(2):16.25. [Internet:https://cberuk.com/cdn/conference_proceedings/conference_39354.pdf; downloaded on 27 July 2020. [ Links ]]

ERDOGAN BZ. 1999. Celebrity Endorsement: A Literature Review. Journal of Marketing Management 15(4):291-314. [Internet:https://doi.org/10.1362/026725799784870379; downloaded on 27 July 2020. [ Links ]]

FORBES K. 2016. Examining the Beauty Industry's Use of Social Influencers. Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications 7(2):78-87. [Internet:https://www.elon.edu/u/academics/communications/journal/wp-content/uploads/sites/153/2017/06/08_Kristen_Forbes.pdf; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

FREBERG K, GRAHAM K, MCGAUGHEY K & FREBERG LA. 2011. Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality. Public Relations Review 37(1):90-92. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.11.001. [ Links ])

GENTILVISO C & AIKAT D. 2019. Embracing the Visual, Verbal, and Viral Media: How Post-Millennial Consumption Habits are Reshaping the News. Studies in Media and Communications 19:147-171. (DOI:10.1108/S2050-206020190000019009. [ Links ])

GLIEM JA & GLIEM RR. 2003. Calculating, Interpreting and Reporting Chronbach's Alpha Reliability Coefficient for Likert-Type Scales. (Midwest research-to-practice conference in adult, continuing and community education. [Internet:https://scholarworks.iupui.edu/bitstream/handle/1805/344/Gliem+&+Gliem.pdf?sequence=1; downloaded on 09 October 2019. [ Links ])

GONZÁLEZ-BENITO O, MARTOS-PARTAL M & FUSTINONI-VENTURINI M. 2015. Brand Equity and Store Brand Tiers: An Analysis Based on an Experimental Design. International Journal of Marketing Research 57(1):73-94. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.2501/IJMR-2015-006. [ Links ])

GODEY B, MANTHIOU A, PEDERZOLI D, ROKKA J, AIELLO G, DONVITO R & SINGH R. 2016. Social media marketing efforts of luxury brands: Influence on brand equity and consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research 69(12):5833-5841. [Internet:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.181; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

GREIFF S & HEENE M. 2017. Why Psychological Assessment Needs to Start Worrying About Model Fit. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 33(5):313-317. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000450. [ Links ])

GUERREIRO C, VIEGAS M & GUERREIRO M. 2019. Social networks and digital influencers: their role in customer decision journey in tourism. Journal of Spatial and Organizational Dynamics 7(3):240-260. [Internet:https://www.jsod-cieo.net/journal/index.php/jsod/article/view/198/164; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

GULLEN JA. 2001. Goodness of fit as a single factor structural equation model. Wayne State University, Detroit, MI. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). [Internet:https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Goodness+of+fit+as+a+single +factor+structural+equation+model&btnG=; downloaded on 27 July 2020. [ Links ]]

HAENLEIN M & KAPLAN AM. 2010. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons 53(1):59-68. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003. [ Links ])

HAIR JF, RISHER JF, SARSTEDT M & RINGLE CM. 2019. When to use and how to report the results of PLS- SEM. European Business Review 31(1):2-24. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203. [ Links ])

HARKER M, BRENNAN R, KOTLER P & ARMSTRONG G. 2015. Marketing: An Introduction. 12th edition, Prentice Hall, Jakarta: Erlangga. [Internet:https://pureportal.strath.ac.uk/en/publications/marketing-an-introduction-3; downloaded on 28July 2020. [ Links ]]

HEGNEY D & CHAN TW. 2010. Ethical challenges in the conduct of qualitative. Nurse researcher 18(1):4-7. (DOI:10.7748/nr2010.10.18.1.4.c8042. [ Links ])

HEINZERLING M. 2018. Effective leadership: Prior research vs. the millennials. Honors Program Theses. [Internet:https://scholarworks.uni.edu/hpt/319; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

HENNIG-THURAU T, MARCHAND A & MARX P. 2009. Can Automated Group Recommender Systems Help Consumers Make Better Choices? Journal of Marketing 76(5):89-109. [Internet:https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1509/jm.10.0537; downloaded on 27 July 2020. [ Links ]]

HENSELER J, RINGLE CM & SARSTEDT M. 2015. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-based Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43(1):115-135. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8. [ Links ])

HUANG N, BURTCH G, GU B, HONG Y, LIANG C, WANG K, FU D & YANGE B. 2019. Motivating UserGenerated Content with Performance Feedback: Evidence from Randomized Field Experiments. Management Science 65(1):327-345. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2017.2944. [ Links ])

HUDSON S & THAL K. 2013. The Impact of Social Media on the Consumer Decision Process: Implications for Tourism Marketing. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 30(1-2):156-160. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2013.751276. [ Links ])

HUGHES C, SWAMINATHAN V & BROOKS G. 2019. Driving Brand Engagement Through Online Social Influencers: An Empirical Investigation of Sponsored Blogging Campaigns. Journal of Marketing 83(5):78-96. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242919854374. [ Links ])

HUTAGALUNG B & SITUMORANG SH. 2018. The Effect Of Social Media Marketing On Value Equity, Brand Equity And Relationship Equity On Young Entrepreneurs In Medan City. (1st Economics and Business International Conference 2017). (DOI:https://doi.org/10.2991/ebic-17.2018.84. [ Links ])

ISMAIL AR. 2017. The influence of perceived social media marketing activities on brand loyalty: The mediation effect of brand and value consciousness. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 29(1):129-144. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-10-2015-0154. [ Links ])

JOSHANLOO M & NIKNAM S. 2019. The Tripartite Model of Mental Well-Being in Iran: Factorial and Discriminant Validity. Current Psychology 38:128-133. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9595-7. [ Links ])

KAPITÄN S & SILVERA DH. 2015. From digital media influencers to celebrity endorsers: Attributions drive endorser effectiveness. Marketing Letters 27(3). (DOI:10.1007/s11002-015-9363-0. [ Links ])

KELMAN HC. 1958. Compliance, identification, and internalization: Three processes of attitude change. Journal of Conflict Resolution 2(1):51-60. [Internet:https://scholar.harvard.edu/hckelman/publications/compliance-identification-and-internalization-three-processes-attitude-change; downloaded 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

KENNY DA. 2019. Enhancing validity in psychological research. American Psychologist 74(9):1018-1028. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000531. [ Links ])

KILINÇ G, YILDIZ E & HARMANCI P. 2018. Bandura's Social Learning and Role Model Theory in Nursing Education. (In book: Health Sciences Research in the Globalizing World, 132-140). [Internet:https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329814373_Bandura's_Social_Learning_and_Role_Model _Theory_in_Nursing_Education; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

KIM AJ & KO E. 2012. Do social media marketing activities enhance customer equity? An empirical study of luxury fashion brand. Journal of Business Research 65(10):1480-1486. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.014. [ Links ])

KIMPAKORN N & TOCQUER G. 2010. Service brand equity and employee brand commitment. Journal of Services Marketing 24(5):378-388. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/08876041011060486. [ Links ])

KING MM & MULTON KD. 1996. The Effects of Television Role Models on the Career Aspirations of African American Junior High School Students. Journal of Career Development 23(2):111-25. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/089484539602300202. [ Links ])

KIVUNJA C & KUYINI AB. 2017. Understanding and Applying Research Paradigms in Educational Contexts. International Journal of Higher Education 6(5):26-41. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v6n5p26. [ Links ])

KLINE RB. 2015. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. Guilford press. New York. [Internet:https://www.guilford.com/books/Principles-and-Practice-of-Structural-Equation-Modeling/Rex-Kline/9781462523344; downloaded on 22 July 2020. [ Links ]]

KNOLL J. 2016. Advertising in social media: A review of empirical evidence. International Journal of Advertising 35(2: 266-300. (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2015.1021898. [ Links ])

KONSTANTOPOULOU A, RIZOMYLIOTIS I, KONSTANTOULAKI K & BADAHDAH R. 2019. Improving SMEs' competitiveness with the use of Instagram Influencer Advertising and eWOM. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 27(2):308-321. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-04-2018-1406. [ Links ])

KOTLER P & KELLER KL. 2009. Marketing Management. International edition. Eleventh Edition. Mullica Pustaka, Jakarta. [Internet:https://books.google.co.za/books/about/Marketing_Management.html?id=c5ejcQAACAAJ&redir_esc=y; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

KRISTOF D, ODEKERKEN-SCHRÖDER G & IACOBUCCI D. 2001. Investments in Consumer Relationships: A Cross-Country and Cross-Industry Exploration. Journal of Marketing 65:33-50. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.65.4.33.18386. [ Links ])

KUMAR R. 2011. Research Methodology: A Step-by-step Guide for Beginners, 3rd edition. SAGE publications. London. [Internet:https://www.amazon.com/Research-Methodology-Step-Step-Beginners/dp/1849203016; downloaded on 20 August 2020 . [ Links ]]

KUMAR V & MIRCHANDANI R. 2012. Increasing the ROI of Social Media Marketing. MIT Sloan Management Review 54(1):55-61. [Internet:http://sloanreview.mit.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/9a4df3d616.pdf; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

LAGRÉE P, CAPPÉ O, CAUTIS B & MANIU S. 2018. Algorithms for Online Influencer Marketing. ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data 13(1):1-30. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/3274670. [ Links ])

LARWIN K & HARVEY M. 2012. A Demonstration of Systematic Item Reduction Approach using Structural Equation Modeling. Research and Evaluation 17(8):1-19. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.7275/0nem-w659. [ Links ])

LEMON KN, RUST RT & ZEITHAML VA. 2001. What Drives Customer Equity. Marketing Management 10(1):20-25. [Internet:http://www.markenlexikon.com/d_texte/customer_equity_drivers_2001.pdf; downloaded on 21 August 2020 . [ Links ]]

LILJANDER V, GUMMERUS J & SÖDERLUND M. 2015. Young consumers' responses to suspected covert and overt blog marketing. Internet Research 25(4):610-632. [Internet:https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-02-2014-0041; downloaded on 27 July 2020. [ Links ]]

LIM XJ, RADZOL AR, CHEAH JH & WONG MW. 2017. The Impact of Social Media Influencers Purchase Intention and the Mediation Effect of Customer Attitude. Asian Journal of Business Research 7(2):19-36. (DOI:10.14707/ajbr.170035. [ Links ])

LIU-THOMPKINS Y & ROGERSON M. 2012. Rising to Stardom: An Empirical Investigation of the Diffusion of User-generated Content. Journal of Interactive Marketing 26(2):71-82. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2011.11.003. [ Links ])

LUXTON S, REID M & MAVONDO F. 2017. IMC capability: antecedents and implications for brand performance. European Journal of Marketing 51(3):421-444. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-08-2015-0583. [ Links ])

MAGNO F, CASSIA F & UGOLINI MM. 2018. Accommodation prices on Airbnb: effects of host experience and market demand. The TQM Journal 30(5):608-620. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-12-2017-0164. [ Links ])

MAKGOSA R. 2010. The influence of vicarious role models on purchase intentions of Botswana teenagers. Young Consumers 11(4):307-319. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/17473611011093934. [ Links ])

MARSH HW, HAU K-T & WEN Z. 2004. In Search of Golden Rules: Comment on Hypothesis-Testing Approaches to Setting Cutoff Values for Fit Indexes and Dangers in Overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler's (1999) Findings. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 11(3):320-341. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2. [ Links ])

MARTENSEN A, BROCKENHUUS-SCHACK S, & ZAHID AL. 2018. How citizen influencers persuade their followers. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 22(3):335-353. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-09-2017-0095. [ Links ])

MCGUIRE WJ. 1985. Attitudes and Attitude Change. In The Handbook of Social Psychology. 3rd Ed. Lindzey G, Aronson E. New York: Random House. (pp 2:233-346. [ Links ])

MCKENZIE S. 2013. Vital statistics: An introduction to Health Science statistics. Sydney, Elsevier. [Internet:https://www.amazon.com/Vital-Statistics-introduction-science-statistics/dp/0729541495; downloaded on 10 September 2020. [ Links ]]

MCNEISH D. 2018. Thanks Coefficient Alpha, We'll Take It From Here. Psychological Methods 23(3):412-433. (DOI:10.1037/met0000144. [ Links ])

METZGER MJ & FLANAGIN AJ. 2013. Credibility and trust of information in online environments: The use of cognitive heuristics. Journal of Pragmatics 59(0):210-220. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2013.07.012. [ Links ])

MIR BERNAL P. 2014. Análisis de la reputación online aplicada al branding de empresa. Estudio comparativo sectorial en gran consume. [Internet:https://www.tesisenred.net/handle/10803/284358; downloaded on 28 July 2020. [ Links ]]

MIYEJAV I. 2017. A Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Mathematics Teachers' Professional Competences (MTPC) in a Mongolian Context. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 14(3):699-708. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.12973/ejmste/80816. [ Links ])

MOOS M, PFEIFFER D & VINODRAI T. 2017. The Millennial City, shaped by contradictions. In Moos M, Pfeiffer D & Vinodrai T. Eds. The millennial city: Trends, implications, and prospects for urban planning and policy. London: Routledge. [Internet:https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9781315209012; downloaded on 22 July 2020. [ Links ]]

MORAR A, VENTER DE VILLIERS M & CHUCHU T. 2015. To vote or not to vote: marketing factors influencing the voting intention of university students in Johannesburg. Journal of Economics and Behavioural Studies 7(6):81-93. [Internet:https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321075213_To_vote_or_not_to_vote_marketing_factors_influ encing_the_voting_intention_of_university_students_in_Johannesburg; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

MORWITZ V. 2014. Consumers' purchase intentions and their behaviour. Foundations, and Trends® in Marketing 7(3):181-230. (DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1561/1700000036. [ Links ])

NOJAVANASGHARI B, GOPINATH D, KOUSHIK J, BALTRUSAITIS T & MORENCY LP. 2016. Deep multimodal fusion for persuasiveness prediction. ICMI '16: (18th ACM International Conference on Multimodal Interaction Deep multimodal fusion for persuasiveness prediction). (pp 284-288). (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/2993148.2993176. [ Links ])

NORTH EJ & KOTZE T. 2001. Parents and television advertisements as Consumer Socialisation Agents for Adolescents: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Family Ecology and Consumer Science 29:91-98. [Internet:https://www.ajol.info/index.php/jfecs/article/view/52806; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

NUNAN D & DIDOMENICO M. 2013. Older Consumers, Digital Marketing and Public Policy: A Review and Research Agenda. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 38(4):469-83. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0743915619858939. [ Links ])

NUNNALLY JC & BERNSTEIN IH. 1994. Psychometric Theory. 3 edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

PALMATIER RW, KUMAR V & HARMELING CM. 2017. Customer Engagement Marketing. Palmgrave MacMillan. New York. (DOI. 10.1007/978-3-319-61985-9. [ Links ])

PANGARIBUAN CH, RAVENIA A & SITINJAK MF. 2019. Beauty Influencer's User-Generated Content on Instagram: Indonesian Millennials Context. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research 8(9):1911-1917. [Internet:http://www.ijstr.org/final-print/sep2019/Beauty-Influencers-User-generated-Content-On-Instagram-Indonesian-Millennials-Context-.pdf; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

PETTY RE, CACIOPPO JT & SCHUMANN D. 1983. Central and Peripheral Routes to Advertising Effectiveness: The Moderating Role of Involvement. Journal of Consumer Research Inc 10(2):135-146. [Internet:http://www.personal.psu.edu/jxb14/M554/articles/Pettyetal1983.pdf; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

POPHAL L. 2016. Influencer Marketing: Turning Taste Makers into Your Best Salespeople. [Internet:http://www.econtentmag.com/Articles/Editorial/Feature/Influencer-Marketing-TurningTaste-Makers-Into-Your-Best-Salespeople-113151.htm; downloaded on 08 May 2020. [ Links ]]

PURWANINGWULAN MM, SURYANA A, WAHYUDIN U & DIDA SS. 2018. The Uniqueness of Influencer Marketing in the Indonesian Muslim Fashion Industry on Digital Marketing Communication Era. Bandung: Atlantis Press. (International Conference on Business, Economics, Social Science and Humanities). (DOI:https://doi.org/10.2991/icobest-18.2018.26. [ Links ])

RANGA M & SHARMA D. 2014. INFLUENCER MARKETING- A MARKETING TOOL IN THE AGE OF SOCIAL MEDIA. Abhinav International Monthly Refereed Journal of Research in Management and Technology 3(8):16-21. [Internet:https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/13e7/35aa017d15e76a658821acb5baf71cf93deb.pdf; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

RAPETTI E & CANTONI L. 2013. Learners of Digital Era between data evidence and intuitions. In Parmigian D, Pennazio V & Traverso A. Eds. Learning & Teaching with Media & Technology. Genua, Italy. (ATEE-SIREM Winter Conference Proceedings. (pp 148-158. [ Links ])

RAYKOV T & MARCOULIDES GA. 2012. A first course in Structural equation modeling. Lawrence Erlbaum associates publishers, London. [Internet:https://www.amazon.com/First-Course-Structural-Equation-Modeling/dp/0805855882; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

RAZZAQ Z, YOUSAF S & HONG Z. 2017. The moderating impact of emotions on customer equity drivers and loyalty intentions: Evidence of within sector differences. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 29(2):239-264. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-03-2016-0053. [ Links ])

REEVES TC & OH EJ. 2007. Do generational differences matter in instructional design? In Spector JM, Merill MD, Van Merrienboer JJG & Driscoll M. (Eds.) Handbook of research on educational communication and technology Mahwah, (pp. 281-304).. [Internet:http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.581.7524&rep=rep1&type=pdf; downloaded on 21 August 2020. [ Links ]]

RIENETTA F, HATI SRH & GAYATRI G. 2017. The Effect of Social Media Marketing on Luxury Brand Customer Equity among Young Adults. International Journal of Economics and Management 11(S2):409-425. [Internet:http://www.ijem.upm.edu.my/vol11_noS2/(8)The%20Effect%20of%20Social%20Media%20M arketing%20on%20Luxury%20Brand%20Customer%20Equity%20Among%20Young%20Adults.pdf; downloaded on 21 July2020. [ Links ]

RIEDLA J & VON LUCKWALD L. 2019. Effects of Influencer Marketing on Instagram. Open Science Publications of Access Marketing Management. (pp 1-37). [Internet:http://www.zbw.eu/econis-archiv/bitstream/handle/11159/3494/AccessMM_Influencer-Marketing_Engl2019_03_29-1.pdf?sequence=1; downloaded on 27 July 2020. [ Links ]]

RIEH SY & DANIELSON DR. 2008. Credibility: A multidisciplinary framework. In Cronin B. Ed. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology. Medford, NJ: Information Today. 41(1):307-364. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/aris.2007.1440410114. [ Links ])

RINKA X & PRATT S. 2018. Social media influencers as endorsers to promote travel destinations: an application of self-congruence theory to the Chinese Generation Y. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 35(7):958-972. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2018.1468851. [ Links ])

ROSARIO, AB, SOTGIU, F, DE VALCK K & BIJMOLT THA. 2016. The Effect of Electronic Word of Mouth on Sales: A Meta-Analytic Review of Platform, Product, and Metric Factors. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.14.0380. [ Links ])

ROSE SA, MARKMAN B & SAWILOWSKY S. 2017. Limitations in the Systematic Analysis of Structural Equation Model Fit Indices. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods 16(1):69-85. (DOI:10.22237/jmasm/1493597040. [ Links ])

ROY S & JAIN V. 2017. Exploring meaning transfer in celebrity endorsements: measurement and validation. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration 9(2):87-104. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/APJBA-06-2016-0058. [ Links ])

RUST RT & VERHOEF PT. 2005. Optimizing the marketing interventions mix in intermediate-term CRM. Marketing Science 24(3): 477-489. [Internet:https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1040.0107; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

SAHELICES-PINTO C & RODRÍGUEZ-SANTOS C. 2014. E-WOM and 2.0 opinion leaders. Journal of Food Products Marketing 20(3):244-261. [Internet:https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2012.732549; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

SAMMIS K, LINCOLN C & POMPONI S. 2016. Influencer Marketing for Dummies. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. [Internet:https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Influencer+Marketing+For+Dummies-p-9781119114093; downloaded on 27 July 2020. [ Links ]]

SANMIGUEL P, GUERCINI S & SÁDABA T. 2018. The impact of attitudes towards influencers amongst millennial fashion buyers. Studies in Communication Sciences 18(2):439-460. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.24434/j.scoms.2018.02.016. [ Links ])

SARIS WE, SATORRA A & VAN DER VELD WM. 2009. Testing Structural Equation Models or Detection of Misspecifications. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 16:561568. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510903203433. [ Links ])

SCHAEFER M. 2012. Return on Influence: The Revolutionary Power of Klout, Social Scoring, and Influence Marketing. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY. [Internet:https://www.amazon.com/Return-Influence-Revolutionary-Scoring-Marketing/dp/0071791094; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

SHAFFER JA, DEGEEST D & LI A. 2016. Tackling the Problem of Construct Proliferation: A Guide to Assessing the Discriminant Validity of Conceptually Related Constructs. Organizational Research Methods 19(1):80-110. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1094428115598239. [ Links ])

SCHIMMACK U. 2019. The Validation Crisis in Psychology. (Preprint). [Internet:https://replicationindex.com/2019/02/16/the-validation-crisis-in-psychology/; downloaded on 10 November 2019. [ Links ]]

SCHUMACHER RE & LOMAX RG. 2010. A beginner's guide to structural equation modeling. 3rd edition. Routledge,NY. [Internet:https://books.google.co.za/books?hl=en&lr=&id=RVF4AgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd &pg=PP1&dq=SCHUMACHER+RE+%26+LOMAX+RG .+2010.+A+beginner%E2%80%99s+guide+to+structural+equation+modeling.&ots=2h7-RIpyzV&sig=SbR_zsszabd8jsfAbMRKcs01nOI&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false; downloaded on 28 July 2020. [ Links ]]

SEGARS AH & GLOVER V. 1993. Re-Examining Perceived Ease of Use and Usefulness: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis. MIS Quarterly 17(4):362-379. [Internet:http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1030.9732&rep=rep1&type=pdf; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

SEILER R & KUCZA G. 2017. Source Credibility Model, Source Attractiveness Model and Match-Up-Hypothesis-An Integrated Model. Journal of International Scientific Publications: Economy & Business 11:1-15. [DOI :https://doi.org/10.21256/zhaw-4720. [ Links ])

SHEN B & BISSELL K. 2013. Social media, Social Me: A Content Analysis of Beauty Companies' Use of Facebook in Marketing and Branding. Journal of Promotion Management 19(5):629-651. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2013.829160. [ Links ])

SHI D, LEE T & MAYDEU-OLIVARES A. 2019. Understanding the model size effect on SEM fit indices. Educational and Psychological Measurement 79(2):310-334. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0013164418783530. [ Links ])

SIMON JP. 2016. User-generated content - users, community of users and firms: toward new sources of co-innovation? INFO 18(6):4-25. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/info-04-2016-0015. [ Links ])

SMITH KT. 2011. Digital Marketing Srategies that Millennials Find Appealing, Motivating, or Just Annoying. Journal of Strategic Marketing 19(6):489-499. (DOI:10.2139/ssrn.1692443. [ Links ])

SMITH KT. 2012. Longitudinal study of digital marketing strategies targeting Millennials. Journal of Consumer Marketing 29(2):86-92. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761211206339. [ Links ])

SOUTH AFRICA. 2008. Consumer Protection Act 68. Pretoria: Government printer. [Internet:https://www.gov.za/documents/consumer-protection-act; downloaded on 28 July 2020. [ Links ]]

SPEARS N & SINGH SN. 2004. Measuring Attitude toward the Brand and Purchase Intentions. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 26(2):53-66. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2004.10505164. [ Links ])

STEIN J. 2013. Millennials: The Me Me Me Generation. Time. 20 May. (26-33). [Internet:https://time.com/247/millennials-the-me-me-me-generation/; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

SUBRAMANIAN S & SUBRAMANIAN A. 1995. Reference Group Influence on Innovation Adoption Behavior: Incorporating Comparative and Normative Referents. European Advances in Consumer Research 2:14-18. [Internet:https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/11642/volumes/e02/E-02; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

TAHERDOOST H. 2016. Sampling Methods in Research Methodology; How to Choose a Sampling Technique for Research. International Journal of Academic Research in Management 5(2):18-27. (DOI:https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3205035. [ Links ])

TEO T, TAN SC, LEE CB, CHAI CS, KOH JHL, CHEN WL & CHEAH HM. 2010. The self-directed learning with technology scale (SDLTS) for young students: An initial development and validation. Computers and Education 55:1764-1771. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.08.001. [ Links ])

PITESA M & THAU S. 2012. Compliant sinners, obstinate saints: how power and self-focus determine the effectiveness of social influence in ethical decision making. Academy of Management Journal 56(3):635-658. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0891. [ Links ])

TILL BD & BUSLER M. 2000. The Match-Up Hypothesis: Physical Attractiveness, Expertise, and the Role of Fit on Brand Attitude, Purchase Intent, and Brand Beliefs. Journal of Advertising 29(3):1-13. (DOI:10.1080/00913367.2000.10673613. [ Links ])

TOMARKEN AJ & WALLER NG. 2005. Structural equation modeling: Strengths, limitations, and misconceptions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 1(1):31-65. (DOI:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144239. [ Links ])

TSAI H-T & BAGOZZI RP. 2014. Contribution Behaviour in Virtual Communities: Cognitive, Emotional, and Social Influences. MIS Quarterly 38(1):143-163. [Internet:https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3955/98b29f2cf6deae802ec9ee662e1180882166.pdf; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

VAN DEN BULTE C, BAYER E, SKIERA B & SCHMITT P. 2018. How Customer Referral Programs Turn Social Capital into Economic Capital. Journal of Marketing Research 55(1):132-46. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.14.0653. [ Links ])

VAN MIERLO H, VERMUNT JK & RUTTE CG. 2009. Composing Group-Level Constructs From Individual-Level Survey Data. Organizational Research Methods 12(2):368-392. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1094428107309322. [ Links ])

VERED A. 2007. Tell A Friend: Word of Mouth Marketing: How Small Businesses Can Achieve Big Results. [Internet:https://www.amazon.com/Tell-Friend-Word-Mouth-Marketing/dp/0615147755; downloaded on 21/07/2020. [ Links ]

VOGEL V, EVANSCHITZKY H & RAMASESHAN B. 2008. Customer Equity Drivers and Future Sales. Journal of Marketing 72:98-108. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1509%2Fjmkg.72.6.098. [ Links ])

WALLS P, PARAHOO K, FLEMING P & MCCAUGHAN E. 2010. Issues and considerations when researching sensitive issues with men: examples from a study of men and sexual health. Nurse Researcher 18(1):26-34. (DOI: 10.7748/nr2010.10.18.1.26.c8045. [ Links ])

WANG MC-H, CHENG JM-S, PURWANTO BM & ERIMURTI K. 2011. The Determinants of the Sports Team Ssponsor's Brand Equity: A Cross-Country Comparison in Asia. International Journal of Market Research 53(6):811-819. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.2501/IJMR-53-6-811-829. [ Links ])

WEISBERG J, TE'ENI D & ARMAN L. 2011. Past purchase and intention to purchase in e-commerce: The mediation of social presence and trust. Internet Research 21(1):82-96. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/10662241111104893. [ Links ])

WEST SG, TAYLOR AB & WU W. 2012. Model fit and model selection in Structural equation modeling. 209-234. New York: Guilford Press. [Internet:https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285751710_Model_Fit_and_Model _Selection_in_Structural_Equation_Modeling; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

WOLF EJ, HARRINGTON KM, CLARK SL & MILLER MW. 2013. Sample Size Requirements for Structural Equation Models: An Evaluation of Power, Bias, and Solution Propriety. Educational and Psychological Measurement 73:913-934. (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0013164413495237. [ Links ])

WONG AT-T. 2019. A Study of Purchase Intention on Smartphones of Post 90s in Hong Kong. Asian Social Science 15(6):78. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v15n6p78. [ Links ])

XIAO M, WANG R & CHAN-OLMSTED S. 2018. Factors Affecting YouTube influencer marketing credibility: a heuristic-systematic model. Journal of Media Business Studies 15(3):188-213. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2018.1501146. [ Links ])

YADAV M & RAHMAN Z. 2018. The influence of social media marketing activities on customer loyalty: A study of e-commerce industry. Benchmarking: An International Journal 25(9):3882-3905. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-05-2017-0092. [ Links ])

YILMAZ SB, ÇELIK HE & YILMAZ V. 2019. HEALTHCARE SERVICE QUALITY - CUSTOMER SATISFACTION: PLS PATH MODEL. Advances and Applications in Statistics 54(2):289-300. (DOI:10.17654/AS054020289. [ Links ])

YU X & YUAN C. 2019. How consumers' brand experience in social media can improve brand perception and customer equity. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics31(5):1233-1251. (DOI:10.1108/APJML-01-2018-0034. [ Links ])

YUAN KH, CHAN W, MARCOULIDES GA & BENTLER PM. 2016. Assessing Structural Equation Models by Equivalence Testing With Adjusted Fit Indexes. Structural Equation Modeling 23(3):319-330. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2015.1065414. [ Links ])

ZEITHAML VA, BITNER MJ & GREMLER DD. 2006. Services marketing: integrating customer focus across the Firm. 2nd ed. Boston: Irwin/McGraw-Hill. [Internet:https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/8339556; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

ZHANG H, KO E & KIM KH. 2012. The Influences of Customer Equity Drivers on Customer Equity and Loyalty in the Sports Shoe Industry: Comparing Korea and China. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 1(2):110-118. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2010.10593063. [ Links ])

ZHANG L, ZHAO J & XU K. 2016. Who creates Trends in Online Social Media: The Crowd or Opinion Leaders? Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 21(1):1-16. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12145. [ Links ])

ZIKMUND WG, BABIN BJ, CARR JC & GRIFFIN M. 2010. Business Research Methods. South-Western, Cengage Learning: Mason, OH. [Internet:https://www.amazon.com/Business-Qualtrics-W-Zikmund-B-J-Babin-J-C-Carr-M-Griffin/dp/B003TNPCEO; downloaded on 21 July 2020. [ Links ]]

* corresponding author