Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Contemporary Management

On-line version ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.17 spe Meyerton 2020

https://doi.org/10.35683/jcm194e.76

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Developing Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy: A Transformative Learning Theory Approach

J NyamundaI; T Van Der WesthuizenII,

IUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal johnnyamunda@gmail.com ORCID NR: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9987-1356

IIUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban. South Africa vanderwesthuizent@ukzn.ac.za ORCID NR: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8795-4023

ABSTRACT

At this time of COVID-19, the world is at the dawn of a new era characterised by a fundamental shift in the way people live, work and conduct relationships. It seems that South Africa, battling with an unemployment rate of 30.1% and economic contraction of 2% in the first quarter of 2020, is not preparing its people with skills for a shift to the new era. Entrepreneurship has been suggested as a viable means to reduce unemployment, and education has been shown to improve entrepreneurial outcomes. South African entrepreneurship education is highly theoretical, borrowing heavily from management courses. The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether the Shifting Hope, Activating Potential Entrepreneurship (SHAPE) social-technology programme developed studentpreneurs to take entrepreneurial action after the thirteen-week systemic action learning and action research initiative (SALAR). The study used a longitudinal research design, where a questionnaire was used to evaluate Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (ESE) before, during and after the training programme. A statistically significant improvement in attitudes towards embarking on entrepreneurial action was observed. Based on this result, participants experienced developmental transformation. Grounded in the developmental transformation that occurred amongst the participants, a Transformative Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (TESE) model was created._

Key phrases: Developmental transformation; drastic transformation; ESE; entrevolutionising; SHAPE; social-technology; transformative learning and transformative self-efficacy model

1. INTRODUCTION

Significant trends in globalisation and technology are shaping the way people must be developed and deployed (World Economic Forum 2017:5). This in turn shapes business models and creates new types of jobs, while making other models and jobs redundant (Willige 2017:Online). These fundamental changes have been accelerated by COVID-19, which has disrupted economies and supply chains, and increased incidences of remote interaction (Czifra & Molnár 2020:39). The South African gross domestic product contracted by 2% in the first quarter of 2020 (South African Reserve Bank 2020:4) and unemployment increased by 1% to 30.1%, while expanded unemployment stood at 39.7% during the same period (Statistics South Africa 2020:8).

These developments drive entrepreneurship development to the fore. Productive entrepreneurs create jobs, influence economic performance, increase innovation and boost productivity (Kritikos 2014:Internet; Trenchard 2015:Internet). Globally, small, medium and micro enterprises (SMMEs) employ 60-70% of the working population and form about 95% of enterprises, while in South Africa SMMEs contribute only 28% of formal jobs (Vuba 2019:Internet). This is despite the National Development Plan 2030 putting economic transformation and job creation at the forefront. According to the NDP 2030, 90% of jobs will be created in SMMEs (National Planning Commission 2012:119). This requires a focus on promoting youth life skills programmes, entrepreneurship training, and opportunities to meaningfully participate in the economy. The institutions best positioned to do this are universities and other vocational training institutions.

2. BACKGROUND TO ENTREVOLUTIONISING TEACHING AND LEARNING

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the challenges that universities face in fulfilling their mandate. Even with significant advances in technology, students still rely heavily on physical presence (Mzileni 2020:Online). This is because a large proportion of students come from impoverished communities not conducive to online learning. Mzileni argues that no technological wizardry can magically solve endemic inequality and poverty.

Even before COVID-19, the education sector was struggling with quality and achievement. South Africa's higher education and training sector ranked 85 out of 137 countries in the Global Competitiveness Report 2017-2018, with the ranking of the quality of the education system worse at 114 (Schwab & World Economic Forum 2018:269). In the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) of 2016, South Africa's average score was 320-180 points below the average of all participating countries (Howie, Combrinck, Roux, Tshele & Mokoena 2017:48). In the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMS) of 2015, South Africa was the lowest performing country for both Maths and Science (Reddy, Visser, Winnaar, Arends, Juan, Prinsloo & Isdale 2016:2). Delving deeper into these numeracy and literacy trends reveals endemic poverty and inequality to be the albatross of the education sector.

According to Gray (2016:Internet), 35% of skills that were considered important five (5) years ago will have changed by 2020. This is due to advances in robotics, artificial intelligence, machine learning, biotechnology and genomics (Gray 2016:Internet). These changes will have a significant impact on employment. Blit, St.Amand and Wajda (2018:3-5) provide three (3) possible employment scenarios: pessimistic, optimistic and sceptical. Under the pessimistic scenario, close to 50% of work tasks will be replaced by artificial intelligence and robotics, resulting in massive unemployment in the next ten to twenty years (Blit et al. 2018:4). In an optimistic scenario, the new technology will lead to the creation of new industries which offer better opportunities. In the sceptical scenario, while technology will put pressure on jobs, resistance by society will slow the devastating impact on job losses (Blit et al. 2018:4). Despite studies showing expected job losses, other studies argue that the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) will enhance integration of physical and cyber systems, which in turn will enhance competitiveness, value creation and quality of life (Gora 2017:143).

The changing nature of the labour market due to the 4IR and COVID-19 is likely to worsen one of South Africa's long-term challenges, that of unemployment. The unemployment statistics are worse for the youth sector (aged 15-34), whose unemployment rate stood at 40.7% for the first quarter of 2020 (Statistics South Africa 2020:9). The South African labour market is characterised by a paradox of high unemployment and shortage of skills (Horwitz 2013:2435).

Significant research into company size and employment shows that smaller and newer companies outperform older and bigger companies in terms of employment creation and growth (Haltiwanger, Jarmin, Kulick, and Miranda 2017). These findings are consistent across different countries, time periods, industries, and research methodology used. This means that increasing entrepreneurial activity is a viable solution to reducing unemployment. As already noted, SMMEs in South Africa only contribute 28% of formal jobs (Vuba 2019:Internet).

A number of researchers point to a positive relationship between education and entrepreneurship development (Do Paco, Ferreira, Raposo, Rodrigues & Dinis 2011; Hannon 2006:296; Hisrich & Brush 1986; Kojo Oseifuah 2010:164; Roffe 2010:141). Hence, upskilling of entrepreneurs through education and training can be seen as a means to improve business survival and employment. However, South African entrepreneurial education has been shown to be highly theoretical and academic, with little practical input (Bletcher 2017). Effective entrepreneurship education should transform students into entrepreneurs and orient them towards entrepreneurial action (Gedeon 2017:2).

The next section will discuss how to develop the entrpreneurial mindset of youth through entrpreneurial education practice. This will be followed by a discussion of the state of entrepreneurship in South Africa, and the role of ESE. A definition of the problem will be provided, research methods, population and sampling. After a discussion of sampling, the article will present the results, followed by a discussion of the implications.

2.1. Transforming entrepreneurship through education and training

Learning is a life-long human endeavour (Merriam & Bierema 2013:ii) that emanates from a person's need to effectively interact with the environment (MacKeracher 2004:80). It is a transformation of experience to knowledge (Kolb 2014:77), and proceeds from the person's desire to reduce uncertainty to a manageable level in order to enhance security and survival (MacKeracher 2004:131-132).

Learning is transformative if it stresses "the critical dimension of learning that enables actors to recognize and reassess the structure of assumptions and expectations, which frame their thinking, feeling, and acting" (Botrom et al, 2018: 2). Such transformation is underpinned by a person's understanding of self, location in the world in relationship to other people, and an understanding of the structures of economic class, gender and race (O'Sullivan, Morrell & O'Connor 2002:88).

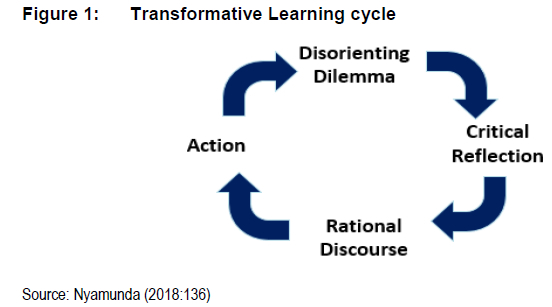

Transformative learning, as a learning theory originally proposed by Mezirow and Marsick (1978), is a multi-step process which begins with a realisation of the need to transform and ends with a shift in fundamental beliefs. Nohl (2015:5) proposes a five-step process to transformative learning, as follows: Step 1 is a non-determining start; Step 2 is experimentation and undirected inquiry; Step 3 is social testing and mirroring; Step 4 is a shift in relevancy; and Step 5 is reinterpretation of individual biography. Kitchenham (2008:119) condensed the 10-step processes propounded by Mezirow and Marsick (1978:12) to four (4) steps, namely: disorienting dilemma, critical reflection, rational discourse, and action. This is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

From Figure 1 it can be observed that transformative learning is a cycle, ongoing and tentative. A person never reaches a point where they are fully transformed (Nyamunda 2018:291; West 2014:167-168). Transformation is needed especially in the 4IR characterised by volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (VUCA) (Kakouris 2015:15).

Due to VUCA, entrepreneurs continue to experience disorientation driven by technology, which can be either sudden and unexpected (Kakouris 2015:15; Merriam 2006:24), or gradual (Mälkki 2012:2; Nohl 2015:5). For transformative learning to occur there needs to be critical reflection, defined as a process of questioning assumptions, beliefs and habits of mind (Mezirow 1997:5). Critical reflection is usually followed by reflective discourse, which is a discourse with other people aimed at exploring their "collective experience" in order to arrive at a tentative judgement (Mezirow 2000:11). Pursuant to this, for any training to be transformative it needs to be cognisant of the transformative learning process.

Central to transformative learning is the person who thinks critically about his/her present circumstances and decides to take action to change these circumstances (Kitchenham 2008:108). Transformation is more than changing what a person knows, but also how they know (Kegan 2000:49). This requires a break from the past (West 2014:170), from a traditional way of seeing things into a self-authoring mindset capable of dealing with ever-increasing pluralism and competing loyalties (Kegan 2000:51). In the context of a studentpreneur, it is referring to an individual attending entrepreneurship classes (Marchand & Hermens 2012:4), taking entrepreneurial action, and launching an entrepreneurial enterprise.

However, there is a different way of evaluating transformation, defined by Ramirez, Gunderson, Levine & Beilock (2013:6) as a shift in developmental maturity. This is characterised by ongoing personal development, which traces the states and developmental stages (O'Fallon 2020:13). In this sense, a programme can lead to real transformation (quantum change, characterised by a break with the past) or developmental transformation (linear change, characterised by gradual ongoing change).

Identity change is the type of transformation that is ideal in student entrepreneurship training. This includes transformation in a person's cognitive functions, learning ability, and social and emotional factors (Illeris 2014:149). Transformative learning in entrepreneurship should lead to a shift in a person's identity from having entrepreneurial dreams to becoming an individual who takes entrepreneurial action (Gedeon 2017:2). It is against this nature of transformation that aspects of entrepreneurship education are discussed next.

2.2. Aspects of entrepreneurship education in South Africa

A review of the effectiveness of South African entrepreneurship education shows mixed results (Nyamunda 2018:60). Several studies show poor results (Mentoor & Friedrich 2007:221; Moodley 2016:55; Steenekamp 2013:iv). For example, South Africa's poor ranking on the Global Competitiveness Report 2017-2018 has already been mentioned (Schwab & World Economic Forum 2018:269). However, Elert, Andersson and Wennberg (2015:20) found a positive relationship between some high school entrepreneurship programmes and the probability of starting a company. Rauch and Hulsink (2015:195) also found that entrepreneurial attitudes and perceived behaviour control increased due to entrepreneurial education.

The results of research conducted by Mentoor and Friedrich (2007:230-231) for a specific university-level entrepreneurship module showed no change in entrepreneurial orientation and achievement orientation, together with a reduction in self-esteem orientation after students completed the module. Similarly, Steenekamp (2013:iv) found no discernible change in entrepreneurial attitudes, entrepreneurial intentions, adaptive cognition or innovative skills for learners who went through the programme run by Junior Achievement South Africa.

Although the study by Moodley (2016:55) is cross-sectional in nature and has a small sample size, it found that 69% of practicing entrepreneurs did not believe that formal education created entrepreneurs.

2.3. The Role of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy in the Entrepreneurship Process

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy emanates from the field of self-efficacy which in turn is rooted in social cognitive theory (Newman, Obschonka, Schwarz, Cohen & Nielson 2018:405).

According to Bandura (2010:29), self-efficacy is a person's perceived ability to perform targeted behaviour. It is a person's self-belief that they can effectively deal with the situation at hand (Karwowski & Kaufman 2017:xviii). Self-efficacy is the most central human agency; that is, a person's belief that they can intentionally influence their life circumstances (Bandura 2010:25). It provides some explanation as to why people are motivated to behave in a certain way (Williams & Rhodes 2016:2).

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy is a domain-specific subset of general self-efficacy. The need for a domain-specific construct helps to introduce nuances relevant to entrepreneurship (Nyamunda 2018:69). Nyamunda (2018:69) defines ESE as the "self-confidence that an individual has in conducting entrepreneurial tasks of opportunity recognition, creating appropriate business relationships, managing an entrepreneurial business and tolerating ambiguity and change".

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy develops from aspects such as vicarious learning, mastery experiences, physiological states and social persuasion (Newman et al. 2018). It is important in entrepreneurship as it is the most direct and immediate reason why nascent entrepreneurs engage in the company creation process (Hechavarria, Renko & Matthews 2012:689). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy is not just important in the start-up process, but also during the implementation of various strategies to make the new business successful (Hechavarria et al. 2012:689). The study by Hechavarria et al. (2012:689) found that nascent entrepreneurs with higher ESE were less likely to give up during difficult times.

Various researchers have proposed different dimensions which make up ESE. For instance, according to Chen, Greene and Crick (1998), ESE is made up of five (5) factors: marketing, innovation, management, risk-taking and financial control. McGee, Peterson, Mueller and Sequeira (2009) advance different dimensions, namely searching for special entrepreneurial opportunity, planning to establish a venture, marshalling relevant resources, implementation and financial management. Other researchers who propose different dimensions of ESE include Barakat, Boddington and Vyakarnam (2014); Barbosa, Gerhardt and Kickul (2007); Zhao, Seibert and Hills (2005) and Denoble, Jung and Ehrlich (1999).

There is growing evidence that ESE can be enhanced through training (Newman et al. 2018:407). Recent research by Abaho, Olomi and Urassa (2015) found that presence of successful entrepreneurs in classes; personal reading, hand-outs and other class activities positively influence a student's ESE. Additional entrepreneurial support services by universities were also shown to increase student ESE (van der Westhuizen & Goyayi 2020) .

3. RESEARCH PROBLEM

The problem with South African entrepreneurship education and training is that it is mostly theoretical and does not use practical exercises such as internships, on-site visits or community development (Ramchander 2019:2; Radipere 2012:11020). Entrepreneurship programmes and courses emphasise theoretical exercises which make students more reactive and less proactive (Van Der Westhuizen 2016:48). If the intention of entrepreneurship education is to produce entrepreneurs, and not "graduate entrepreneurs", then all entrepreneurial education should orient students towards taking entrepreneurial action (Gedeon 2017:2).

4. THE SOCIAL TECHNOLOGY OF SHIFTING HOPE, ACTIVATING POTENTIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP

The SHAPE social technology on which this research is based aims to increase participants' ESE. Social technology is a process of innovation, conducted collectively and participatively by actors interested in building that desirable scenario. The training programme component of SHAPE is voluntary, which is not part of the curriculum (Nyamunda & van der Westhuizen 2017:7). The programme is guided by Theory U, which aims to achieve transformation by heightening an individual's state of attention, enabling them to shift and transform (Scharmer & Kaufer 2013:7).

The duration of the specific SHAPE programme that was studied was thirteen weeks, in lecture theatres at the Westville campus of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, from 18 July 2017 to 24 October 2017. The SHAPE programmes are relatively more experiential than the usual university academic modules, making use of several entrepreneurs as presenters of different topics. The presenting entrepreneurs are selected based on their speciality and experience. Students engage in a variety of group discussions, complete a business model canvas, and are encouraged to exhibit their business during the certificate ceremony.

The SHAPE programme was selected for study because it promised to be more experiential than typical academic modules. In addition, the setup of the programme made it possible to conduct a longitudinal study to evaluate the transformation in the participants' ESE.

5. RESEARCH AIM, OBJECTIVES AND HYPOTHESES

This research aimed to evaluate whether there was student transformation after the SHAPE training programme and to create a model for transformative learning, based on the longitudinal empirical findings that can be applied to develop elements of ESE.

The key objectives of the study were as follows:

• To determine if participation in the SHAPE training programme transformed the participants' ESE.

• To develop a training model which leads to ESE transformation. It is hypothesised that:

H0 : The SHAPE programme does not transform students' ESE to take entrepreneurial action.

H1 : The SHAPE programme transforms students' ESE to take entrepreneurial action.

6. RESEARCH QUESTION

To what extent does the SHAPE social technology transform participants' ESE to take entrepreneurial action?

7. RESEARCH METHODS AND DESIGN

The study followed a pragmatic action research paradigm which assumes that reality is not stable but constantly renegotiated, debated and interpreted in terms of its usefulness for a given situation (Patel 2015:Internet). Pragmatism does not take a world view about truth and reality and focuses mostly on trying to solve the problem at hand (Feilzer 2010:1). In this study, the problem at hand was posed as to whether there was transformation of students after attending the SHAPE programme.

The study used a longitudinal research design where the same questionnaire was used to evaluate ESE before, during and after SHAPE training. The researchers developed the questionnaire, consisting of thirty-one questions. Two (2) questions were open-ended, twenty-eight were based on a 5-point Likert scale, and one 91) was a closed "Yes" or "No" question. For those questions using the 5-point Likert scale, the response options were balanced between two-positive and two-negative. The middle option was as far as possible neutral, and a "not-applicable" was not provided.

To increase reliability of the questionnaire, a pilot study was conducted on twenty students who had similar biographical characteristics as the population of interest. The twenty people in the pilot were all students at a local university. The pilot respondents completed the self-administered questionnaire and returned it to the researchers. A preliminary data analysis was done on the results of the pilot study using Statistical Package for Social Science. Cronbach's Alpha was calculated and the items with an Alpha of greater than 0.6 were retained. The questions which loaded poorly were dropped.

Every questionnaire included a letter to the respondent highlighting that their participation was voluntary and confidential. The questionnaires were distributed to participants immediately before the training session. Respondents completed them individually and handed them back at the end of the study session. There was no discussion of the questionnaire during the session, except to say that participants were encouraged to complete and hand back the questionnaire. Data was initially captured into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet; during analysis using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), only the student number or identity number was retained as a unique identifier. Completed questionnaires were stored in a locked cabinet in a researcher's office.

8. POPULATION AND SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICS

The target population for this study was third-year students at a South African public university enrolled in a three (3) or four (4) year degree programme. There were approximately 2,000 third-year students who fitted these criteria.

The study sample was convenient as participants chose to respond to posters advertising the SHAPE training programme. A non-probability sampling strategy was selected because of the nature of the research being conducted. For a truly random sample to be selected, the characteristics of the entire population about the research matter must be known (Marshall 1996:523) and have an equal chance of being selected (Sekaran & Bougie 2010:242). Participants who responded to the study questionnaire had self-selected at two levels: firstly, by participating in the SHAPE programme; and secondly, by agreeing to complete the questionnaire. Table 1 shows respondents to the study.

Table 1 show that females were considerably more represented than males in the three (3) rounds of the study (56.5/43.5% in Round 1, 26.4/16.7% in Round 2 and 57.1/38.9% in Round 3). Of interest is that in Round 2 a substantial number of respondents did not indicate their gender.

The overall sample was consistent in terms of gender composition, when compared to the 2015 general university student population, which was 58.11% female and 41.88% male (Council of Higher Education 2016). For participants who took part in all three (3) rounds of the study, females were 65% of the total, and males were 35%. This implies that females were somewhat over-represented in the sample of participants who took part in all rounds of the study.

The study received ethical clearance from the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal on 14 July 2017. The Protocol Reference Number is HSS/1045/017D.

9. RESULTS, FINDINGS AND DISCUSSIONS

The results of the study are presented below.

9.1 Entrepreneurial action results

The questionnaire was intended for a larger study into developing ESE through transformative learning. Relevant for this article were four (4) questions specifically aimed at identifying the change in participants' willingness to take entrepreneurial action. The four (4) Likert scale questions were:

• I act in a way which can help me identify opportunities to start a business

• I act in a way which can help me have new ideas of finding a market and/or geographic territory for a product or service of choice

• I act in a way which can help me manage my own business.

• I act in a way which can help me work under pressure, stress and constant change experienced if you own a business

The questions sought to evaluate entrepreneurial action in terms of the following elements of ESE (Barbosa et al. 2007):

• Identifying entrepreneurial opportunities

• Generating new ideas for finding a market for a product or service

• Ability to manage own business, and

• Dealing with pressure, stress and constant change

The aggregate scores for respondents were calculated and the results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 show that there was a general increase in means from Round 1 to Round 3 for willingness to take entrepreneurial action, based on the aggregate scores. Although there were considerable increases in means from Round 1 to Round 3, the change from Round 1 to Round 2 was higher than the increase from Rounds 2 to 3. This is further illustrated in Figure 2.

The changes from Round 1 to 3 were 37.3% for all-rounds participants and 43.4% for all participants. However, while the change from Round 1 to 2 was 32.8% for all respondents, it was only 25.7% for respondents who completed all questionnaires. These increases reduced to 8% for all respondents from Round 2 to 3 and 9.3% for those respondents who completed all questionnaires.

9.2 Hypothesis Testing

To further analyse the implication of these results, they were tested against the two hypotheses of this study. The hypotheses, as specified above, are as follows:

H° : The SHAPE programme, like numerous other entrepreneurship programmes, does not transform students' ESE to take entrepreneurial action.

H1 : The SHAPE programme transforms students' ESE to take entrepreneurial action.

To test the significance of change over time, the following multivariate tests were used; Pillai's Trace, Wilks' Lambda, Hotelling's Trace and Roy's Largest Root. All these tests perform the same function (Grande 2015:Internet), and Wilks' Lambda was the preferred statistical test for reporting. There was a statistically significant increase in participants' attitude towards taking entrepreneurial action after the SHAPE training programme: Wilk's Λ= 0.457, F (2, 55.0) = 30.881, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.543.

These results lead to the rejection of the null hypothesis (H°) and acceptance of the alternative hypothesis (H1) that there was a significant change to participants' attitude towards taking entrepreneurial action following their attending the SHAPE training workshop.

10. DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

Previous research did not specifically evaluate whether there was student ESE transformation after attending a training programme. Studies in the area of training and change in ESE show mixed results.

For instance, Fayolle and Gailly (2015:75) found that for students without any background in entrepreneurship, the entrepreneurial programme they were evaluating led to no increase in entrepreneurial intention immediately after the programme. Six (6) months later, however, those students without entrepreneurial background showed a significant increase in entrepreneurial intent. Elert et al. (2015:20) found a positive relationship between a high school entrepreneurship education programme and the probability of starting a company. Rauch and Hulsink (2015:199) indicated an increase in entrepreneurial attitudes and perceived behaviour control.

Conversely, the results from Mentoor and Friedrich (2007:221) showed no change in entrepreneurial orientation and achievement orientation, plus a reduction in self-esteem orientation. Steenekamp (2013:iv) found no discernible change in entrepreneurial attitudes, entrepreneurial intentions, adaptive cognition or innovative skills for learners who went through the programme run by Junior Achievement South Africa.

While the research indicates a statistically significant increase in developmental transformation, previous research highlights that a high level of desire does not automatically lead to entrepreneurial action (Brännback & Carsrud 2017:3; Iwu, Ezeuduji, Eresia-Eke & Tengeh 2016:179). Researchers such as Brännback and Carsrud (2017:3) propose that there is a need for a non-volitional push to convert intentions into entrepreneurial action. Iwu et al.'s (2016) research (ibid. :6) found that most of their respondents had a desire to initiate their own business but reported that they faced challenges in turning their intention into reality. For people to start a business, therefore, a training programme needs to lead to real transformation - a break from the past.

To evaluate the level of transformation achieved by the SHAPE programme participants, this study relied on self-administered questions framed thus: 'I act in a way that can help me identify opportunities...' or 'I act in a way that can help me manage my own business'. Though this study successfully demonstrated developmental transformation, it failed to evaluate transformation as set by Gedeon (2017:2). Taking entrepreneurial action in the world is complex and requires more than answering questions more positively. It requires participants to be exposed to real entrepreneurial world experiences. Thus, a more immersive training model - the TESE model - is proposed.

10.1 The Transformative Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (Apprenticeship) Model

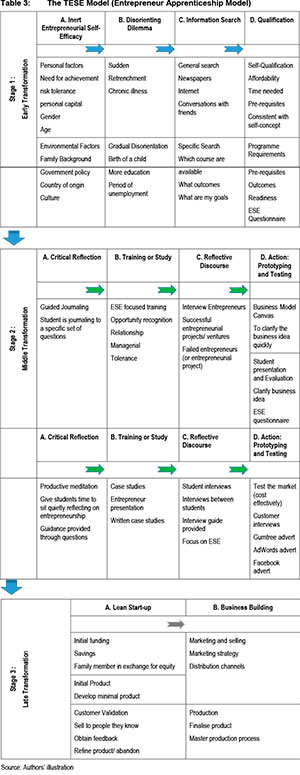

Based on the longitudinal empirical findings, the TESE model proposes that transformation of ESE occurs in three stages: early transformation, middle transformation and late transformation. This is illustrated in Table 3.

Stage 1: Early Transformation

The first stage is the preliminary aspect of the TESE model. It explores the aspects which drive a person to consider entrepreneurship training. Personal and environmental factors pre-dispose a person's propensity to exploring entrepreneurship training. Disorienting experiences can be sudden - such as retrenchment - or may occur gradually over a long period of time, such as with lack of career growth. These disorienting experiences prompt a person to explore alternatives. The individual usually begins with an undirected information search (Nohl 2015:15), and concludes their search by considering training courses available. The early transformation stage concludes with an individual applying to join a formal training programme, and the programme evaluating whether he or she meets the qualifying criteria. Refer to Table 3.

Every programme needs to have qualifying criteria to select people who are most likely to be successful after having been subjected to it. This is achieved by evaluating individual entrepreneurial traits such as need for achievement, risk tolerance, persistence, and personal and social capital, together with any other competences needed for that specific course (Ferreira, Marques, Bento, Ferreira & Jalali 2015:2695). Once participants have been evaluated for potential transformation, the next stage is middle transformation.

Stage 2: Middle Transformation

Middle transformation involves the training process which can be divided into critical reflection, reflective discourse, and prototyping or idea testing. Critical reflection in terms of this model is characterised by the trainer using journaling or productive meditation. The student writes in a diary or meditates on specific ESE-oriented questions. Critical reflection sets the participant up for the training, as they reflect on why they want further training. Ideally, short guided journaling or productive meditation should precede every training session. The formal training processes should as far as possible be conducted by practising entrepreneurs, and focus specifically on transforming existing experiences, knowledge, skills and attitudes. Students should also go through written small business case studies which have a special focus on elements of ESE.

To maintain momentum towards transformation, students will interview entrepreneurs about their successful and unsuccessful business ideas or ventures. After these interviews, students interview each other, focusing on what they believe are the key ingredients which lead to success or failure of an entrepreneurial activity. They should connect this to their own experiences of interviewing entrepreneurs. Thereafter, students should create entrepreneurial prototypes (working models) which they use to gather customer feedback (Noyes 2018:131). This stage concludes with students testing their business ideas as cost effectively as possible. The idea of testing is for students to see if there is a market for their product or service, using this information to refine their idea. Refer to Table 3 above.

Stage 3: Late Transformation

Late transformation signals the end of formal training and the student engages in the formal start-up process. This involves two ongoing processes: lean start-up and business building. Lean start-up involves raising a small amount of money and starting as cost-effectively as possible, to minimise risk. The business is still trying to prove that it satisfies a need that clients will pay for. During lean start-up, the entrepreneur is still trying to calibrate the offering and build a track record among customers and financers. Only when the product is reasonably successful should the individual start the business-building process. During business building, the entrepreneur keeps refining the product, but the focus is on putting in place systems to improve the chances of business success.

11. LIMITATIONS

This study was subject to three (3) main weaknesses. The first is that the study contains a self-selection bias. Participants who participated in the SHAPE programme elected to attend the programme, and those who completed the questionnaires also self-selected. This limited the generalisability of the results (Asthana & Braj 2016:17). The second weakness is that the proposed TESE model has not been tested in a practical entrepreneurship training environment to determine its effectiveness. A third weakness is that the research relied to a large extent on self-reports. Self-reports are unreliable as they are unduly influenced by attitude, cognitive limitations, mood and personality (Spector 1994).

12. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Based on the above, the following recommendations are suggested:

Firstly, entrepreneurship courses should expose studentpreneurs to the reality of owning and running a business. Part of exposing studentpreneurs to this reality involves them interviewing entrepreneurs with specific focus on their successful and failed business ventures. This helps potential entrepreneurs get a sense of what it really takes to start and run a successful business.

Secondly, every entrepreneurship training programme should have qualifying criteria. This can be done through using a questionnaire to evaluate studentpreneurs' level of desire and relevant entrepreneurial traits which will likely lead to success. The qualifying criteria help increase the chances of student transformation, since only people ready for the training are selected.

Thirdly, entrepreneurship training should be mindful of the ever-changing technological environment. Students of entrepreneurship should be taught to be cognisant of the impact of technology on levels of competition, automation and agility.

13. MANAGERIAL TRAINING RECOMMENDATIONS

Most people are in constant fear of change, and transformation requires a break from the socialising experience (West 2014:167). Kegan (2000:49) summarises the problem as follows: educators interested in transformation need to better understand their students' current epistemologies to create appropriate learning designs. Likewise, managerial training should try to understand trainees' existing epistemologies before and during the training process. This would help the trainees incorporate new concepts into what they already do.

Managerial training, like entrepreneurship training, should be participative. Trainees should practice the skill for which they are being trained under the instructor's guidance. This allows them to get feedback before they do it in a work setting.

As in entrepreneurship training, role models are vital. Managerial trainers should use managerial role models as much as possible during training. Role models would help transmit to trainees what really works and what does not work in the real work environment.

This article highlights the two (2) types of transformation: drastic transformation and developmental transformation. Drastic transformation is characterised by a sudden break with the past, while developmental transformation is the gradual ongoing personal improvement as a result of ongoing experiences. This distinction is important to understand in order to reduce the ongoing confusion in transformative learning literature.

The TESE model highlights the importance of personal and environmental factors in the training process. The value which a trainee derives from any training programme is influenced by these different factors that they bring to the programme, and the success of any practice-oriented programme depends on taking these factors into account.

14. CONCLUSION

In this article, it was argued that entrepreneurship is a key long-term solution to unemployment. But entrepreneurial training to increase ESE and reduce business failure has been shown to be ineffective (Mentoor & Friedrich 2007:231; Moodley 2016:55; Steenekamp 2013:iv). Because they are mostly theoretical, most South African entrepreneurship courses are designed to produce entrepreneurship "graduates" (Radipere 2012:11017). While the SHAPE social technology was shown to increase developmental transformation, the study could not impute drastic transformation. As a consequence, a TESE Model is proposed. The proposed three-stage TESE model could support entrepreneurship students in changing their existing mindsets about entrepreneurship and give them an opportunity to develop and test their business ideas in a guided environment. The implications for this study are that managerial training programmes should be practical, use practitioners as role models, and take into account trainees' mental models.

15. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is based on research supported in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant Number:122002-Shape).

REFERENCES

ABAHO E, OLOMI D & URASSA G. 2015. Students' entrepreneurial self-efficacy: Does the teaching method matter? Education and Training 57:908-923. (DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/et-02-2014-0008. [ Links ])

ASTHANA H & BRAJ B. 2016. Statistics For Social Sciences (With SPSS Applications). PHI Learning. [ Links ]

BANDURA A. 2010. Self efficacy. Encyclopedia of Human Behavior 4:71-81. (DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781412952576.n182. [ Links ])

BARAKAT S, BODDINGTON M & VYAKARNAM S. 2014. Measuring entrepreneurial self-efficacy to understand the impact of creative activities for learning innovation. The International Journal of Management Education 12:456-468. (DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2014.05.007. [ Links ])

BARBOSA S, GERHARDT M & KICKUL J. 2007. The role of cognitive style and risk preference on entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies 13:86-104. (DOI: 10.1177/10717919070130041001. [ Links ])

BLETCHER T. 2017. Findings on entrepreneurship in the SA university system, and the broader context of entrepreneurship in the South African public education system. Pretoria. Entrepreneurship Development in Higher Education. (Lekgotla 16 March 2017. [ Links ])

BLIT J, ST.AMAND S & WAJDA J. 2018. Automation and the future of work: scenarios and policy options. CIGI Papers No. 174. (May 2018. [ Links ])

BRÄNNBACK M & CARSRUD AL. 2017. Revisiting the entrepreneurial mind: inside the black box: an expanded edition. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. [ Links ]

CHEN CC, GREENE PG & CRICK A. 1998. Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing 13(4):295-316. (DOI:10.1016/s0883-9026(97)00029-3. [ Links ])

COUNCIL OF HIGHER EDUCATION. 2016. VitalStats Public Higher Education 2015. Pretoria: Council of Higher Education. [ Links ]

CZIFRA G & MOLNÁR Z. 2020. COVID-19 and Industry 4.0. Sciendo 28(46):36-45. (DOI:10.2478/rput-2020-0005. [ Links ])

DO PACO A, FERREIRA J, RAPOSO M, RODRIGUES RG & DINIS A. 2011. Entrepreneurial intention among secondary students: findings from Portugal. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 13(1):92-106. DOI:10.1504/ijesb.2011.040418. [ Links ])

DENOBLE A, JUNG D & EHRLICH S. 1999. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: The development of a measure and its relationship to entrepreneurial action. In Reynolds PD. (Ed). Frontiers of entrepreneurship research. Center for Entrepreneurial Studies. Center for Entrepreneurial Studies, Babson College, Stanford, CA (1999). (pp 73-87. [ Links ])

ELERT N, ANDERSSON FW & WENNBERG K. 2015. The impact of entrepreneurship education in high school on long-term entrepreneurial performance. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 111:209-223. (DOI:10.1016/j.jebo.2014.12.020. [ Links ])

FAYOLLE A & GAILLY B. 2015. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: hysteresis and persistence. Journal of Small Business Management 53(1):75-93. (DOI:10.1111/jsbm.12065. [ Links ])

FEILZER MY. 2010. Doing mixed methods research pragmatically: implications for the rediscovery of pragmatism as a research paradigm. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 4:6-16. (DOI:10.1177/1558689809349691. [ Links ])

FERREIRA FA, MARQUES CS, BENTO P, FERREIRA JJ & JALALI MS. 2015. Operationalizing and measuring individual entrepreneurial orientation using cognitive mapping and MCDA techniques. Journal of Business Research 68:2691-2702. (DOI:10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.04.002 . [ Links ])

GEDEON SA. 2017. Measuring student transformation in entrepreneurship education programs. Education Research International. Vol. 2017 (DOI:https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8475460. [ Links ])

GORA Z. 2017. The 4th Industrial Revolution and innovative labour trends, challenges, forecasts. Chala Nina, Poplavska Oksanab [Internet:https://www.ceeol.com/search/chapter-detail?id=719682; downloaded on 16 October 2020. [ Links ]]

GRANDE T. 2015. Conducting a repeated measures ANOVA in SPSS. YouTube. [Internet:https://youtu.be/vhLS1yPax6M; downloaded on 28 July 2020. [ Links ]]

GRAY A. 2016. The 10 skills you need to thrive in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. World Economic Forum [Internet:https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-10-skills-you-need-to-thrive-in-the-fourth-industrial-revolution/; downloaded on 31 July 2020. [ Links ]]

HANNON PD. 2006. Teaching pigeons to dance: sense and meaning in entrepreneurship education. Education &Training 48(5):296-308.( DOI:10.1108/00400910610677018. [ Links ])

HALTIWANGER J, JARMIN RS, KULICK R & MIRANDA J. 2017. Measuring Entrepreneurial Businesses: Current Knowledge and Challenges. Chicago: . University of Chicago Press. (ISBNS: 978-0-226-45407-8. [ Links ])

HECHAVARRIA DM, RENKO M & MATTHEWS CH. 2012. The nascent entrepreneurship hub: goals, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and start-up outcomes. Small Business Economics 39(3):685-701. (DOI:10.1007/s11187-011 -9355-2. [ Links ])

HISRICH RD & BRUSH C. 1986. Characteristics of the minority entrepreneur. Journal of Small Business Management 24(1). [Internet:https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1-4587539/characteristics-of-the-minority-entrepreneur; downloaded on 01 August 2020. [ Links ]]

HORWITZ FM. 2013. An analysis of skills development in a transitional economy: the case of the South African labour market. International Journal of Human Resource Management. (DOI:10.1080/09585192.2013.781438. [ Links ])

HOWIE S, COMBRINCK C, ROUX K, TSHELE M & MOKOENA G. 2017. PIRLS LITERACY 2016: Progress in International Reading Literacy Study 2016. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

ILLERIS K. 2014. Transformative learning and identity. Journal of Transformative Education 12:148-163. (DOI:10.4324/9780203795286. [ Links ])

IWU CG, EZEUDUJI I, ERESIA-EKE C & TENGEH R. 2016. The entrepreneurial intention of university students: the case of a university of technology in South Africa. 12(1):164-181. [Internet:http://hdl.handle.net/2263/60902; downloaded on 16 August 2020. [ Links ]]

KAKOURIS A. 2015. Entrepreneurship pedagogies in lifelong learning: emergence of criticality? Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 6:87-97. (DOI:10.1016/j.lcsi.2015.04.004. [ Links ])

KARWOWSKI M & KAUFMAN JC. 2017. The creative self: effects of beliefs, self-efficacy, mindset and identity. London: Academic Press. [ Links ]

KEGAN R. 2000. What "form" transforms? In ASSOCIATES JM (ed.) Learning as transformation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. (pp 164-179). (DOI:10.4324/9781315147277-3. [ Links ])

KITCHENHAM A. 2008. The evolution of John Mezirow's transformative learning theory. Journal of Transformative Education 6:104-123. (DOI: 10.1177/1541344608322678. [ Links ])

KOJO OSEIFUAH E. 2010. Financial literacy and youth entrepreneurship in South Africa. African Journal of Economic And Management Studies 1(2):164-182. (DOI:10.1108/20400701011073473. [ Links ])

KOLB DA. 2014. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Michigan: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

KRITIKOS AS. 2014. Entrepreneurs and their impact on jobs and economic growth. IZA World of Labor 2014:8. (DOI :10.15185/izawol .8. [ Links ])

MARCHAND J & HERMENS A. 2012. Student entrepreneurship: a research agenda. International Journal of Organisational Innovation 8(2):266-282. [Internet:https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282370614_Student_Entrepreneurship_a_Research_Agenda;downloaded on 16 September 2020. [ Links ]]

MACKERACHER D. 2004. Making sense of adult learning. Totonto: University of Toronto Press. [ Links ]

MÄLKKI K. 2012. Rethinking disorienting dilemmas within real-life crises: the role of reflection in negotiating emotionally chaotic experiences. Adult Education Quarterly 62:207-229. (DOI:10.1177/0741713611402047. [ Links ])

MARSHALL MN. 1996. Sampling for qualitative research. Family Practice 13(6):522-526. (DOI:10.1093/fampra/13.6.522. [ Links ])

MCGEE JE, PETERSON M, MUELLER SL & SEQUEIRA JM. 2009. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy: Refining the Measure. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 33(4):965-988. (DOI:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00304.x. [ Links ])

MENTOOR ER & FRIEDRICH C. 2007. Is entrepreneurial education at South African universities successful? Industry & Higher Education 21(3):221-232. (DOI:10.5367/000000007781236862. [ Links ])

MERRIAM SB & BIEREMA LL. 2013. Adult learning: linking theory and practice. San Francisco: Wiley. [ Links ]

MERRIAM SB. 2006. Transformational learning and HIV-positive young adults. Theoretical Frameworks in Qualitative Research 1:23-38. (DOI:10.4135/9781412986335.n2. [ Links ])

MEZIROW J & MARSICK V. 1978. Education for perspective transformation. Women's Re-entry Programs in Community Colleges. Centre for Adult Education Teachers College, Columbia University. [ Links ]

MEZIROW J. 1997. Transformative learning: theory to practice. New directions for adult and continuing education 1997:5-12. (DOI:10.1002/ace.7401. [ Links ])

MEZIROW J. 2000. Learning to think like an adult. Learning as transformation: critical perspectives on a theory in progress. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. (pp 3-33. [ Links ])

MOODLEY S. 2016. Creating entrepreneurs in South Africa through education. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. (MBA project). [Internet:http://hdl.handle.net/2263/59883; downloaded on 21 August 2020. [ Links ]]

MZILENI P. 2020. How Covid-19 will affect students. pnternet:https://mg.co.za/education/2020-04-23-how-covid-19-will-affect-students/; downloaded on 19 July 2020. [ Links ]]

NATIONAL PLANNING COMMISSION. 2012. National Development Plan 2030. Pretoria: National Planning Commission. [ Links ]

NEWMAN A, OBSCHONKA M, SCHWARZ SM, COHEN MB & NIELSEN I. 2018. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy: Antecedents, Outcomes, and Agenda for Future Research. Academy of Management Proceedings 1:10204. (DOI:https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2018.10204abstract. [ Links ])

NOHL A-M. 2015. Typical phases of transformative learning: a practice-based model. Adult Education Quarterly 65:35-49. (DOI:10.1177/0741713614558582. [ Links ])

NOYES E. 2018. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy 1:118-134. (DOI:10.1177/2515127417737289. [ Links ])

NYAMUNDA J. 2018. Developing entrepreneurial self-efficacy: a transformative learning theory approach. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (PhD Business Management thesis. [ Links ])

NYAMUNDA J & VAN DER WESTHUIZEN T. 2017. Youth Unemployment: The role of Transformative Learning in making the youth explore entrepreneurship. Journal of Contemporary Management 15:314343. [Internet:https://journals.co.za/content/journal/10520/EJC-152673cc51; downloaded on 15 August 2020. [ Links ]]

O'FALLON. 2020. States and stages: waking up developmentally. Integral Review 16(1):13-38. [Internet:https://integral-review.org/issues/vol_16_no_1_ofallon_states_and_stages.pdf; downloaded on 15 August 2020. [ Links ]]

O'SULLIVAN E, MORRELL A & O'CONNOR MA. 2002. Expanding the boundaries of transformative learning: essays on theory and praxis. New York:Springer. [ Links ]

PATEL S. 2015. The research paradigm-methodology, epistemology and ontology-explained in simple language. [Internet:http://salmapatel.co.uk/academia/the-research-paradigm-methodology-epistemology-and-ontology-explained-in-simple-language; downloaded on 25 February 2017. [ Links ]]

RADIPERE S. 2012. South African university entrepreneurship education. African Journal of Business Management 6:11015-11022. (DOI:10.5897/ajbm12.410. [ Links ])

RAMCHANDER M. 2019. Reconceptualising undergraduate entrepreneurship education at traditional South African universities. Acta Commercii 19(2):a644. (DOI:10.4102/ac.v19i2.644. [ Links ])

RAMIREZ G, GUNDERSON EA, LEVINE SC & BEILOCK SL. 2013. Math anxiety, working memory, and math achievement in early elementary school. Journal of Cognition and Development 14(2):187-202. (DOI:10.1080/15248372.2012.664593. [ Links ])

RAUCH A & HULSINK W. 2015. Putting entrepreneurship education where the intention to act lies: an investigation into the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial behavior. Academy of Management Learning and Education 14(2):187-204. (DOI: 10.5465/amle.2012.0293. [ Links ])

REDDY V, VISSER M, WINNAAR L, ARENDS F, JUAN A, PRINSLOO C & ISDALE K. 2016. TIMSS 2015 highlights of mathematics and science achievement of Grade 9 South African learners. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

ROFFE I. 2010. Sustainability of curriculum development for enterprise education: observations on cases from Wales. Education & Training 52(2):140-164. (DOI:10.1108/00400911011027734. [ Links ])

SCHARMER CO & KAUFER K. 2013. Leading from the emerging future: from ego-system to eco-system economies. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. [ Links ]

SCHWAB K & WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM. 2018. The Global Competitiveness Report 2017-2018. World Economic Forum. [Internet:http://www3.weforum.org/docs/GCR2017-2018/05FullReport/TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2017%E2%80%932018.pdf ; downloaded on 31 July 2020. [ Links ]]

SEKARAN U & BOUGIE R. 2010. Research methods for business: a skill building approach. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN RESERVE BANK. 2020. Quartetly Bulletin June 2020. Pretoria: South African Reserve Bank. [ Links ]

SPECTOR P. 1994. Using self?report questionnaires in OB research: A comment on the use of a controversial method. Journal of organizational behaviour 15(5):385-392. (DOI: 10.1002/job.4030150503. [ Links ])

STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA. 2020. Quarterly Labour Force Survey, Quarter 1: 2020. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. (Statistical Release P0211. [ Links ])

STEENEKAMP A. 2013. An assessment of the impact of entrepreneurship training on the youth in South Africa. Potchefstroom, South Africa: North-West University. (PhD thesis. [ Links ])

VAN DER WESTHUIZEN T & GOYAYI MJ. 2020. The influence of technology on entrepreneurial self-efficacy development for online business start-up in developing nations. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 21(3):168-177. (DOI:10.1177/1465750319889224. [ Links ])

VAN DER WESTHUIZEN T. 2016. Developing individual entrepreneurial orientation: a systematic approach through the lens of Theory U. Durban: University of KwaZulu Natal. (PhD thesis. [ Links ])

VAN DER WESTHUIZEN T. 2017. Theory U and Individual Entrepreneurial Orientation in developing youth entrepreneurship in South Africa. Journal of Contemporary Management 14(1):531-553. [Internet:https://journals.co.za/content/journal/10520/EJC-94301931 a; downloaded on 15 August 2020. [ Links ]]

VUBA S. 2019. The missed opportunity: SMMEs in the South African economy. [Internet:https://mg.co.za/article/2019-04-12-00-the-missed-opportunity-smmes-in-the-south-african-economy/; downloaded on 19 July 2020. [ Links ]]

TRENCHARD R. 2015. What impact do entrepreneurs have on society? [Internet:https://www.virgin.com/entrepreneur/what-impact-do-entrepreneurs-have-society; downloaded on 19 July 2020. [ Links ]]

WEST L. 2014. Transformative learning and the form that transforms: towards a psychosocial theory of recognition using auto/biographical narrative research. Journal of Transformative Education 12:164-179. (DOI:10.1177/1541344614536054. [ Links ])

WILLIAMS DM & RHODES RE. 2016. The confounded self-efficacy construct: conceptual analysis and recommendations for future research. Health Psychology Review 2016 10(2):113-128. (DOI:10.1080/17437199.2014.941998. [ Links ])

WILLIGE A. 2017. How do we make sure our children are fluent in digital?. [Internet:https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/01/ways-to-prepare-kids-for-jobs-of-future/; downloaded on 02 April 2020. [ Links ]]

WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM. 2017. Realizing human potential in the Fourth Industrial Revolution: an agenda for leaders to shape the future of education, gender and work. Geneva: World Economic Forum. [ Links ]

ZHAO H, SEIBERT S & HILLS G. 2005. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology 90:1265-1272. (DOI:10.1037/0021 -9010.90.6.1265. [ Links ])

* corresponding author