Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Law, Democracy and Development

On-line version ISSN 2077-4907Print version ISSN 1028-1053

Law democr. Dev. vol.26 Cape Town 2022

https://doi.org/10.17159/2077-4907/2021/ldd.v26.4

ARTICLES

Black economic empowerment in South Africa: Is transformation of the management structures of enterprises as essential as it should be?

Jeannine Van De Rheede

Lecturer, Department of Mercantile and Labour Law, University of the Western Cape, South Africa; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3403-6525

ABSTRACT

Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) was launched as an integrated policy initiative to empower black people and redistribute wealth across the spectrum of South Africa's population. The Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act 53 of 2003, as amended in 2013, was enacted to correct the imbalances of apartheid and promote transformation of the economy. The Codes of Good Practice adopted in terms of the Act were promulgated to provide a standard by which the BEE rating of enterprises can be calculated. BEE ratings are important to enterprises since enterprises use them to attract and retain clients: the higher an enterprise's BEE rating, the more it is likely to benefit financially. It is for this reason that it is in most enterprises' interests to have a good BEE rating. The BEE rating of an enterprise is calculated by using the rules and formulae in the Codes of Good Practice. However, despite the objectives of the Act, enterprises are able to obtain good BEE ratings even where a low percentage of black people form part of their management structures. It is important to determine how this is possible. This article exposes shortcomings in the existing BEE legal framework that make it possible for enterprises to obtain good BEE ratings under such circumstances.

Keywords: Black economic empowerment; Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act 53 of 2003; fronting practices; management; ownership; race; transformation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Under apartheid, South Africa enacted laws that resulted, inter alia, in a gross imbalance between white and black people insofar as their participation in the economy was concerned.1 Businesses owned by black people were only allowed to operate in limited areas.2 The government also placed restrictions on the education that black people could access, and prescribed the types of employment positions they could occupy.3

Since 1994, however, the view of the government has been that "South Africa requires an economy that can meet the needs of all its citizens".4 The Constitution provides that, in order "to promote the achievement of equality, legislative and other measures designed to protect or advance persons, or categories of persons, disadvantaged by unfair discrimination may be taken".5 Parliament has undertaken a number of legislative efforts aimed at remedying the racial imbalances of apartheid and the country's historical legacy of workplace discrimination. These efforts include the enactment of the Employment Equity Act (EEA),6 the Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act (PEPUDA),7 and the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act (B-BBEEA), which was subsequently amended.8

The EEA applies to workplace discrimination, while the PEPUDA applies to persons who are excluded from the scope of the EEA.9 The B-BBEEA, as amended, governs black economic empowerment (BEE). BEE was initiated to rectify the inequalities caused by apartheid and to enhance the economic participation of black people.10 The beneficiaries of the B-BBEEA are black people. "Black people" is a generic term that refers to:

"Africans, Coloureds, Indians and Chinese -

(a) who are citizens of the Republic of South Africa by birth or descent; or

(b) who became citizens of the Republic of South Africa by naturalisation

(i) before 27 April 1994; or

(ii) on or after 27 April 1994 and who have been entitled to acquire citizenship by n naturalisation prior to that date".11

The B-BBEEA was enacted, inter alia, to "achieve a substantial change in the racial composition of ownership and management structures and in the skilled occupations of existing and new enterprises"12 and to "promote economic transformation in order to enable meaningful participation of black people in the economy".13 The Codes of Good Practice promulgated in terms of the B-BBEEA provide the rules and formulae that enterprises have to use to determine their BEE ratings.

The purpose of this article is to determine what shortcomings in the legal framework make it possible for some enterprises to obtain good BEE ratings despite the low percentage of black people in their management structures. Accordingly, the article examines the manner in which BEE ratings are determined, the ratings of enterprises, the extent of representation of the racial groups in management positions within enterprises, and the provisions in the B-BBEEA and Codes of Good Practice (B-BBEE Codes) enacted in terms of it. This will be followed by a discussion of fronting practices and provisions in the B-BBEEA that are designed to prevent them. The article concludes by presenting the author's views on shortcomings in the legal framework that enable enterprises to obtain good BEE ratings in the circumstances mentioned above.

2 THE B-BBEEA AND B-BBEE CODES

Subject to the exceptional circumstances discussed below, compliance with the B-BBEEA is voluntary for enterprises in the private sector; however, BEE affects almost every participant in the South African economy in one way or another.14 BEE is important to enterprises not only in obtaining but retaining business.15 It is vital for an enterprise to have a good BEE rating, since some customers choose service providers based on their BEE rating.16 The level of the BEE rating can thus provide competitive advantage when entities are competing for the same business.17

This is particularly so when it comes to tenders for government work, where it is imperative for an enterprise to have a good BEE rating.18 In terms of the Codes of Good Practice, organs of state, public entities19 and all measured entities which undertake any business activities with public entities and organs of state are required to be BEE-compliant.20 An entity is also required to be BEE-compliant where such an entity undertakes a business activity with any other entity that is required to comply with the Codes of Good Practice and who seeks to be BEE-compliant.21 Even in circumstances where private enterprises do not enter into transactions with organs of state or public entities or with other entities that are required to comply with the Codes of Good Practice, there is pressure towards compliance, "given the supply chain effect of supplier compliance in order to secure business".22 Such circumstances arise where private companies seek to obtain business from other private companies that require their service providers to be BEE-compliant. This is similarly the case in various transactions with financial institutions that are reluctant to lend funds or provide business to non-compliant enterprises.23

The objective which is most relevant to this discussion is found in section 2(b) of the B-BBEEA. It states that one of the objectives of the B-BBEEA is "to achieve a substantial change in the racial composition of ownership and management structures of enterprises". In view of this, it is essential to determine how some enterprises are able to obtain good BEE ratings even when they have not changed the racial composition of their management structures. The B-BBEE Codes refer to enterprises that use the Codes to calculate their BEE status as "measured entities".24 The rules and formulae contained in the B-BBEE Codes prescribe the methodology to be followed in determining the BEE rating of enterprises.

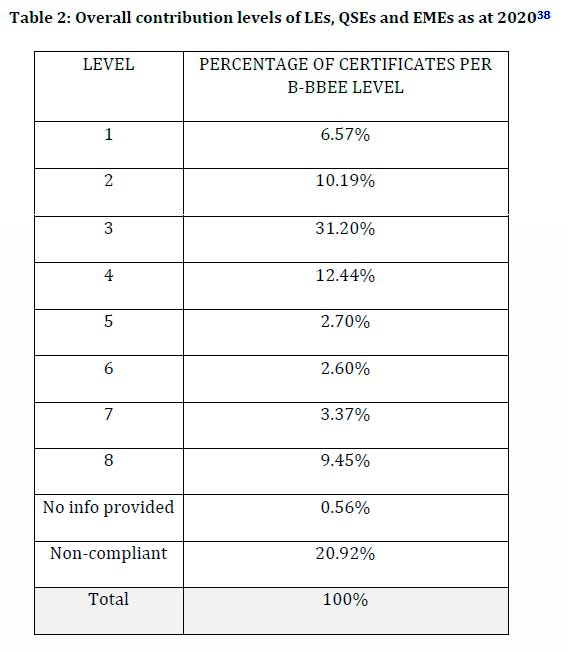

The B-BBEE Codes contain five elements. Code series 100 and 600 are the Codes governing the ownership element;25 Code series 200 and 602 govern the management control element;26 Code series 300 and 603 govern the skills development element;27Code series 400 and 604 govern the enterprise and supplier development element;28and Code series 500 and 605 govern the socio-economic development element.29 The table below sets out the manner in which the BEE rating of a measured entity is determined.

The table above present eight contribution levels and their respective recognition levels.30 The measured entity receives points based on its overall performance,31 which will determine its corresponding BEE recognition level and contribution level.32 An entity that scores less than 40 points is deemed to be non-compliant.

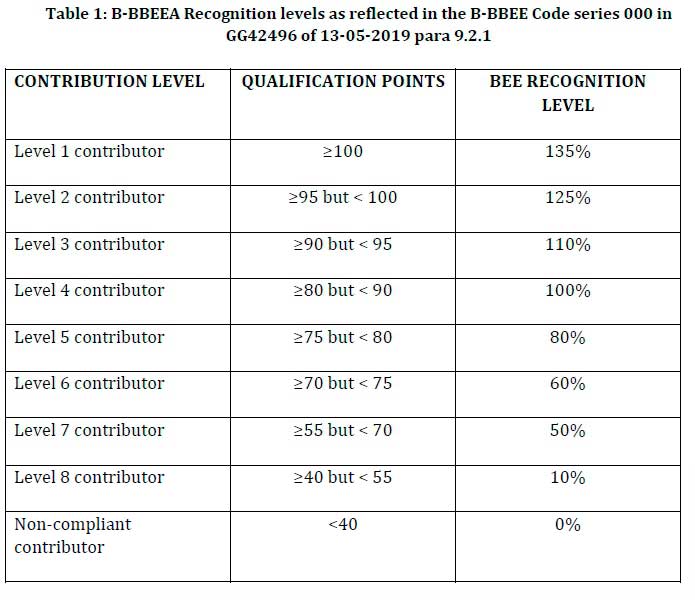

Measured entities are divided into four categories: an exempted micro-enterprise (EME);33 a start-up enterprise;34 a qualifying small enterprise (QSE);35 and a large enterprise (LE).36 Enterprises are able to obtain good BEE ratings despite the low percentage of black people who form part of the racial composition of their management structures. The achievement of these good BEE ratings is evident from the BEE certificates of enterprises that are displayed online and from the reports compiled by the B-BBEE Commission37 on national trends in broad-based black economic empowerment. The table below combines the overall contribution levels of LEs, QSEs and EMEs as reflected in the B-BBEE Commission's report.

The figures reflected in the table above indicate that a higher percentage of enterprises have BEE ratings from level 1 to level 5 than at levels 6-8 . As a result of the BEE ratings being in this range (level 1 to level 5) as opposed to the lower range (level 6 to non-compliant), this shows that enterprises have good BEE ratings. The representation of black people in management structures is outlined below in Tables 3 and 4.

3 THE EXTENT OF REPRESENTATION OF RACIAL GROUPS IN MANAGEMENT POSITIONS

Management is defined as "a set of activities (including planning, decision-making, organising, leading and controlling) directed at an organisation's resources (human, financial, physical and information) with the aim of achieving organisational goals in an effective and efficient manner".39 Black people face hurdles in the workplace that impede their growth by making it difficult for them to enter the management structures of the enterprises that employ them.40 These hurdles include the corporate cultures of enterprises as well as unequal opportunities within them.41 The tables below show the extent to which population groups are represented in top and senior management.

Tables 3 and 4 show that change in the racial composition of the management structures of enterprises has occurred, but at a slow pace. The tables confirm that there has been a decline in white people occupying positions at the levels of both top management (with the exception of 2011 and 2015) and senior management (with the exception of 2015). In addition, it shows that the percentage of African people at both the levels of top management and senior management has increased (with the exception of 2011 and 2015 in top management and 2015 and 2016 in respect of senior management); however, they remain under-represented.44 The figures reflected in the tables confirm that there is a low percentage of black people who form part of the management structures of enterprises.

The B-BBEEA and B-BBEE Codes were enacted, inter alia, to transform the managerial structures of enterprises and to assist black people in gaining employment at management level.45 It is important to determine how it is possible for enterprises to obtain good BEE ratings in circumstances where there is a low percentage of black people who form part of their management structures when the B-BBEEA was enacted with the objective of ensuring transformation in South Africa. The BEE rating of an enterprise is measured by making use of the rules and formulas contained in the B-BBEE Codes.46 The B-BBEE Codes contain scorecards which are discussed below.

4 BEE SCORECARDS AND THE PRIORITY ELEMENTS

The B-BBEE Codes contain two scorecards: the Generic scorecard and the Qualifying Small Enterprise (QSE) scorecard. The score obtained by a measured entity is determined by making use of either the Generic or the QSE scorecards. A start-up enterprises is regarded as an EME, unless such an enterprise is tendering 'for a contract that is in excess of the threshold for EMEs in which case the corresponding scorecard will apply'.47 'An EME is deemed to have a BEE status of level four contributor having a recognition level of 100%',48 however in circumstances where an EME is 51% black owned, such an EME qualifies for elevation to a BEE recognition level of 125%.49Despite the aforementioned, where an EME is 100% black owned, such an enterprise qualifies for elevation to a BEE level one contributor with a BEE recognition level of 135%.50 Despite the aforementioned an EME is allowed to be measured by making use of the QSE scorecard.51 A QSE is required to comply with all the elements.52 A QSE which is at least 51% black owned 'qualifies for elevation to a level two contributor having a BEE recognition level of 125%'53 and where a QSE is 100% black owned such an enterprise qualifies for elevation to a BEE level one contributor having a BEE recognition level of 135%.54 Other QSEs55 should be measured under the QSE scorecard.56 A LE is required to use the Generic scorecard. The said scorecards are set out below.

As the table shows, the highest points are allocated to enterprise and supplier development, ownership and skills development. This acts as an incentive to encourage enterprises to comply more with these elements, as opposed to complying with the management control element.

Similar to the Generic scorecard, the QSE scorecard allocates the highest points to ownership, enterprise and supplier development, and skills development. Again, the fact that the highest points have been allocated to these elements is an incentive to enterprises to which the QSE scorecard applies to comply more with them. However, in both scorecards the points allocated to the management control element should have been higher than those allocated to skills development and enterprise and supplier development. One would assume that the high points allocated to the ownership element in both the Generic and QSE scorecards would have had some effect on the transformation of management structures, but, as acknowledged by the BEE Commission when commenting on the fact that LEs scored the lowest in the management control element, "notwithstanding high ownership percentages, shareholders appear to have limited influence in driving transformation at management levels".57

The fact that high points have been allocated to skills development, as well as to enterprise and supplier development, in comparison to management control, is a shortcoming in the legal framework that makes it possible for enterprises to obtain good BEE ratings despite the low percentage of black people in their management structures.

There are three priority elements: ownership, skills development and enterprise and supplier development. A LE should comply with all the priority elements58 while a QSE 'is required to comply with ownership as a compulsory element and either skills development or enterprise and supplier development with the exclusion of black owned QSEs'.59 The fact that management control does not form part of one of the priority elements is one of the shortcomings of the legal framework that make it possible for enterprises to obtain a good BEE rating, despite the low percentage of black people who form part of their management structures.

One of the possible reasons that the legislature allocated less points to management control and did not make management control a priority element could be related to the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Commission's60 decision to adopt the maximalist61 as opposed to the minimalist approach to BEE.62 If the minimalist approach were adopted, the management control element would have been prioritised. While adopting the maximalist approach at the time BEE was initiated was the appropriate decision - given that the maximalist approach aims to close the gap between the rich and the poor - with nearly two decades having passed since BEE's initiation and noting the limited extent to which black people are represented in management structures, continuing on this basis may make it difficult to achieve the objective contained in section 2(b) of the B-BBEEA.

Opportunity hoarding is also relevant in determining the reason why enterprises choose to obtain a good BEE rating by complying with elements other than management control. Opportunity hoarding is discussed below.

5 OPPORTUNITY HOARDING

Research has shown that the advancement of black professional employees is hindered by a phenomenon known as opportunity hoarding.63 Opportunity hoarding occurs when those in dominant positions in an enterprise reserve these positions for persons of their own racial group.64 Management control and socio-economic development are the two elements that are not priority elements, and are the elements to which the lowest points are allocated in both the Generic and QSE scorecards. Where those in dominant positions are involved in opportunity-hoarding practices, in circumstances where an enterprise is unable to comply fully with the priority elements, such an enterprise would be forced to obtain points by complying with management control and socioeconomic development. The enterprise then would be more likely to choose to comply more with socio-economic development, rather than management control, to ensure that positions are preserved for persons from their own racial group. The involvement in opportunity hoarding practices may thus discourage enterprises from obtaining a good BEE rating by complying fully with management control.

Opportunity hoarding is possible because white dominant enterprises are able to obtain good BEE ratings by means other than advancing black employees, such as by means of complying more with the elements of enterprise and supplier development and socio-economic development. Good BEE ratings are also obtained by enterprises in circumstances where fronting practices are committed by such enterprises. These practices are discussed below.

6 FRONTING PRACTICES

The commission of fronting practices affects the BEE rating of an enterprise. Fronting practices are defined by the B-BBEA as "a transaction, arrangement or other act or conduct that directly or indirectly undermines or frustrates the achievement of the objectives of the B-BBEEA or the implementation of any of the provisions of the B-BBEEA".65 Section 1 of the B-BBEEA contains a number of practices that fall within the scope of fronting practices.66 In circumstances where fronting practices are committed, enterprises deliberately contravene the provisions in the B-BBEEA by misrepresenting facts about the extent of their compliance.67 In essence, fronting is seen as "tokenism for the superficial inclusion of historically disadvantaged individuals with no actual transfer of wealth or control".68 What this implies is that the provisions in the B-BBEEA and the B-BBEE Codes are manipulated to such an extent that it amounts to fraud.69

The objective of an enterprise committing a fronting practice is to prove that the enterprise is BEE-compliant when this is not the case, or to prove that an enterprise has a BEE recognition level higher than what that enterprise is entitled to. The wording used by the legislature in the definition of fronting comprises the three most commonly known forms of fronting, namely, window-dressing, benefit diversion, and the use of opportunistic intermediaries.70

An example of benefit diversion is found in the case of Swifambo Rail Leasing (Pty) Ltd v Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa [PRASA].71 In this judgment, the Supreme Court of Appeal held that the arrangement between Vossloh and Swifambo constituted a fronting practice for a number of reasons. The first is that Vossloh was not BEE-compliant, while Swifambo had a BEE rating of level four.72 Swifambo was thus merely a "token participant" who received funds in exchange for Vossloh's use of Swifambo's BEE rating. Secondly, Swifambo was a front for Vossloh, because in the bid in question Vossloh was described as the subcontractor; however, all the services that were rendered under the PRASA contract were rendered by Vossloh, while Swifambo played a minimal role.73 Finally, Swifambo's personnel played no role when it came to PRASA and there was no skills transfer, while Vossloh had complete control over the contract concluded between PRASA and Swifambo.74

An example of a fronting practice in the form of window-dressing is found in Peel and others v Hamon J&C Engineering (Pty) Ltd and Others75. Here, Hamon & Cie (International SA) sold its shares in Hamon SA (Pty) Ltd to two black women. This was done for the purpose of improving the BEE rating of Hamon SA (Pty) Ltd.76 In terms of the agreement for the sale of shares concluded between the parties, 13% of the shares were sold to each woman; however, the two black women shareholders did not participate in any of the company's decision-making processes.77

These cases illustrate that fronting practices have the effect of showing that an enterprise is BEE-compliant when this is not in fact the case. Additionally, while improving the BEE rating of an enterprise, such a change in the BEE rating does not necessarily arise as a result of black people being placed in management positions. Enterprises' involvement in fronting practices can result in enterprises obtaining good BEE ratings even in circumstances where there is a low percentage of black people who form part of the management structures of these enterprises.

Procurement officers, verification agencies and other corporate decision-makers are encouraged to report any fronting behaviour to the Department of Trade and Industry.78 The B-BEEA contains enforcement measures designed to eliminate the commission of fronting practices. As mentioned, the B-BBEEA establishes a Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Commission (the Commission)79 which has jurisdiction throughout South Africa.80 The functions of the Commission are, inter alia:

"to oversee, supervise and promote adherence with this Act in the interest of the public";81

"to receive complaints relating to broad-based black economic empowerment in accordance with the provisions of this Act";82

"to investigate, either on its own initiative or in response to complaints received, any matter concerning broad-based black economic empowerment";83 [and]

"to receive and analyse such reports as may be prescribed concerning broad-based black economic empowerment compliance from organs of state, public entities and private sector enterprises".84

While these functions provided to the Commission are valuable in ensuring compliance with the B-BBEEA, they are not useful in all circumstances. One of the functions of the Commission is to oversee and supervise adherence with the B-BBEEA, but compliance with the B-BBEEA is voluntary when it comes to private enterprises that do not undertake business activities with organs of state or public entities or any other measured entity that is required to comply with the Codes of Good Practice. As such, there is no obligation on such private enterprises to comply with the provisions of the B-BBEEA and thus no reason for the Commission to exercise any supervisory functions in respect of the aforementioned enterprises who do not comply.

The Commission is also tasked with the function of analysing reports received from organs of state and public and private enterprises as far as BEE compliance is concerned; however, the B-BBEEA requires only public entities, spheres of government, organs of state,85 public companies listed on the JSE,86 and Sectoral Education and Training Authorities87 to report on compliance. Given that private enterprises are not required to submit such reports, the Commission would not be able to exercise this function over those of them that choose not to submit a report. However, where private enterprises comply with the B-BBEEA and submit their reports, the Commission is able to exercise the aforementioned functions in respect of such entities.

In circumstances where the provisions contained in the B-BBEEA are contravened, or in the event of there being any complaints regarding BEE, the B-BBEEA has included provisions relating to the relief that may be obtained by aggrieved parties and the procedure to be followed to obtain it. The Commission has the power to investigate any matter that relates to the application of the B-BBEEA88 and is empowered to make a finding as to whether an initiative amounts to a fronting practice.89

The Commission may also institute legal proceedings in a court to restrain any breach of the B-BBEEA, "including any fronting practice, or to obtain appropriate remedial relief".90 In addition, the B-BBEEA allows the Commission to publish any finding or recommendation it made as far as the outcome of an investigation is concerned.91 In the event of the B-BBEE Commission being of the opinion that the investigated matter involves the commission of a criminal offence, the Commission is required to refer the matter to an appropriate division of the South African Police Service, or the National Prosecuting Authority.92

One of the most important features of the B-BBEEA is its criminalisation of fronting in terms of section 13(0)(1). A person commits an offence if that person knowingly:

"misrepresents or attempts to misrepresent the broad-based black economic empowerment status of an enterprise;

provides false information or misrepresents information to a B-BBEE verification professional in order to secure a particular broad-based black economic empowerment status or any benefit associated with the compliance of this Act;

provides false information or misrepresents information relevant to assessing the broad-based black economic empowerment status of an enterprise to any organ of state or public entity; or engages in a fronting practice."93

The number of offences that have been created by the B-BBEEA is a step in the right direction in the legislature's effort to combat fronting. The B-BBEEA's provision for the criminal liability of additional parties where they fail to report to the appropriate law enforcement agency in the event of their knowledge of the commission or attempted commission of an offence94 has been described as an effective deterrent.95This is because these parties96 are positioned to detect contraventions of the B-BBEEA.97 However, this may not be an effective deterrent in all circumstances. Fronting has become so sophisticated that some black people are unaware they are being used for fronting.98 The additional parties to whom criminal liability has been extended will also seldomly be aware of the extent of the fronting that takes place.

As far as sanctions are concerned, a person who knowingly commits a fronting practice will be liable to pay a fine and/or be imprisoned for a period not exceeding ten years or both a fine and imprisonment and companies can face an administrative penalty of up to 10% of their annual turnover.99 The B-BBEEA also prohibits any individual who has been found guilty of an offence from doing business with public entities or organs of state for up to ten years.100 The B-BBEEA provides a number of punitive measures against enterprises and other parties who choose to circumvent its objectives; however, these measures are not always effective. Despite the fact that a legislative framework has been provided to combat fronting, fronting practices are still being committed.101

The fact that enterprises commit fronting practices while the aforementioned measures are in place shows that these measures are not as effective as they should be, and it further illustrates that as far as some enterprises are concerned, the main objective is to obtain or improve their BEE rating, no matter how they go about doing it. This shows that for some enterprises, obtaining a good BEE rating is merely a "tick-box" exercise. The fact that the punitive measures are not always effective is thus an additional shortcoming of the legal framework that allows enterprises to obtain good BEE ratings despite the low percentage of black people in their management structures.

7 CONCLUSION

In order to dismantle apartheid, legislation was enacted to promote transformation, with the B-BBEEA being one such statute and its aim being to facilitate BEE. The objective of BEE is to redress the inequalities caused by apartheid by providing black people with economic benefits which previously were not available to them. Only a low percentage of black people form part of the management structures of enterprises, since shortcomings in the legal framework make it possible for enterprises to obtain good BEE ratings without having transformed their management structures.

The first shortcoming of the legal framework is that in terms of the B-BBEEA Codes there are three priority elements. A LE is required to comply with all three priority elements, while a QSE is required to comply with ownership as a compulsory element and either skills development or enterprise and supplier development. Management control is not a compulsory element in respect of either a LE or a QSE. Management control also does not form part of either one of the two priority elements with which a QSE is required to comply. This would enable a LE and QSE to obtain more points in respect of the priority elements without having much regard for management control.

The second shortcoming is that the points weighting allocated to ownership, skills development and enterprise and supplier development, is higher than what has been allocated to management control. Enterprises will thus be encouraged to comply more with the priority elements and may even obtain points under the socio-economic development element with less consideration for the management control element.

A third shortcoming contributing to the slow pace of transformation within the management structures of enterprises relates to opportunity hoarding, where dominant positions are reserved for persons of a particular racial group. In circumstances where white people in dominant positions reserve these positions for persons of their own racial group and enterprises are unable to comply fully with the priority elements, such an enterprise may choose to comply more with the socio-economic development element than with management control to assist in preserving dominant positions for persons from their own racial group. One of the reasons that opportunity hoarding is possible is due to the fact that enterprises can obtain good BEE ratings by complying more with the priority elements and with socio-economic development than with management control.

A fourth shortcoming of the legal framework that makes it possible for enterprises to obtain good BEE ratings despite the low percentage of black people in management is due to enterprises' involvement in fronting practices. The legislature has included a number of sanctions in the event of fronting practices being committed; however, research shows that these practices continue despite the sanctions.

The shortcomings of the legal framework identified above show that it is possible for enterprises to obtain good BEE ratings despite the low percentage of black people who form part of their management structures. This may change in the event of higher points being awarded for compliance with the management control element, or in the event of management control becoming one of the priority elements for a LE and a QSE. It is essential that the aforementioned changes be made urgently, given the likely impacts on the efforts aimed at eliminating inequalities in South Africa.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Balshaw T & Goldberg J Broad-based black economic empowerment amended codes and scorecard 3ed (2014) NB Publishers [ Links ]

Gqubule D Making mistakes righting wrongs: Insights into black economic empowerment (2006) Jonathan Ball Publishers [ Links ]

Griffin RW Management 12ed (2015) South-Western Cengage Learning [ Links ]

M'Paradzi A & Kalula E Black economic empowerment in South Africa: A critical appraisal (2007) Institute of Development and Labour Law, University of the Cape Town [ Links ]

Journal Articles

Horwitz FM & Jain H "An assessment of employment equity and broad based black economic empowerment developments in South Africa" (2011) 30 Equality Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 297-316 [ Links ]

Osode PC "The new broad-based economic empowerment act: A critical evaluation" (2004) 18 Speculum Juris 114 [ Links ]

Pooe RID "The latest 'big thing' for South African companies: Enterprise and supplier development - Proposing an implementation framework" (2016) 10(1) Journal of Transport and supply chain management 235-246 [ Links ]

Ponte S & Roberts S "Black empowerment, business and the state in South Africa" (2018) 38(5) Development and Change 933-955 [ Links ]

Pruitt LR "No black names on the letterhead? Efficient discrimination and the South African legal profession" (2002) Michigan Journal of International Law 545-676 [ Links ]

Seate BM & Pooe RID "The relative importance of managerial competencies for predicting the perceived job performance of broad-based black economic empowerment verification practitioners" (2016) South African Journal of Human Resource Management 696-705 [ Links ]

Sibanda A "Weighing the cost of BEE fronting on best practices of corporate governance in South Africa" (2015) 29 Speculum Juris 23-40 [ Links ]

Warikandwa TV & Osode PC "Regulating against business 'fronting' to advance black economic empowerment in Zimbabwe: Lessons from South Africa" (2017) Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal 1-27 [ Links ]

Wright EO "Understanding class towards an integrated analytical approach" (2009) 60 New Left Review 101-116 [ Links ]

Constitutions

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Legislation

Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act 53 of 2003

Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Amendment Act 46 of 2013

Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Codes code series 600 GN38766 of 6 May 2015

Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Codes code series 000 in GG 42496 of 31 May 2019

Employment Equity Act 55 of 1998

Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act 4 of 2000

Case Law

CSARS v NWK (27/10) (2010) ZASCA 168

Esorfranki Pipelines v Popani District Municipality (40/13) (2014) ZASCA 21

Roschcon (Pty) Ltd v Anchor Auto Body Builders CC and others 2014 (4) SA 319 SCA

Peel and others v Hamon J&C Engineering (Pty) Ltd and Others 2013(2) SA 331 (GSJ)

Swifambo Rail Leasing (Pty) Ltd v. Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa 2020 (1) SA 76 (SCA)

Viking Pony Africa Pumps (Pty) Ltd t/a Tricom Africa v Hidro-Tech Systems (Pty) Ltd and Another 2011 (2) BCLR 207 (CC)

Conference Proceedings

Chauke KR "Broad-based black economic empowerment (B-BBEE) as a competitive advantage in conducting business in South Africa" (2020) The 5th Annual International Conference on Public Administration and Development Alternatives 07-09 October 2020, Virtual Conference 571-579 [ Links ]

Reports

B-BBEE Commission National status and trends on broad-based black economic empowerment report (2020)

Department of Labour Commission for Employment Equity annual report (2013-2014)

Department of Labour Commission for Employment Equity annual report (2016-2017)

Department of Labour Commission for Employment Equity annual report (2018-2019)

Department of Labour Commission for Employment Equity annual report (2019-2020)

Newspapers

Nkomo SM "Why white men still dominate the top echelons of South Africa's private sector" The Conversation 4 August 2015 [ Links ]

Internet Sources

CRRC E-LOCO Supply (Pty) Ltd v Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Commission & Others Case No. 34701/19 available at https://www.ensafrica.com/uploads/newsarticles/0 bbeee%20judgement.pdf (accessed 3 November 2021) [ Links ]

Levenstein K "Starting a business: How can B-BBEE help me?" available at www.showme.co.za/lifestyle/starting-a-business-how-can-b-bbee-help-me/ (accessed 3 November 2021) [ Links ]

Smith C "BEE fronting becoming more sophisticated, holding back transformation -commission" available at https://www.fin24.com/Economy/bee-fronting-becoming-more-sophisticated-holding-back-transformation-commission-20190627-2 (accessed 13 September 2021) [ Links ]

1 Chauke KR "Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (B-BBEE) as a competitive advantage in conducting business in South Africa" (2020) The 5th Annual International Conference on Public Administration and Development Alternatives 7-9 October 2020 Virtual Conference 571 at 574.

2 Ponte S & Roberts S "Black empowerment, business and the state in South Africa" (2018) 38(5) Development and Change 933 at 941.

3 Pruitt LR "No black names on the letterhead? Efficient discrimination and the South African legal profession" (2002) Michigan Journal of International Law 545 at 557.

4 See Chauke (2020) at 574.

5 Section 9(2) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996.

6 Employment Equity Act 55 of 1998.

7 Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act 4 of 2000.

8 Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act 46 of 2013.

9 Section 5(3) of PEPUDA.

10 Balshaw T & Goldberg J Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Amended codes and scorecard 3ed Cape Town: Tafelberg (2014) at 13.

11 Section 1 of the B-BBEEA.

12 Section 2(b) of the B-BBEA.

13 Section 2(a) of the B-BBEEA.

14 See Balshaw & Goldberg (2014) at 14. See also Levenstein K "Starting a business: How can B-BBEE help me?" available at www.showme.co.za/lifestyle/starting-a-business-how-can-b-bbee-help-me/ (accessed 3 November 2021).

15 See generally Levenstein (2021). See also Balshaw & Goldberg (2014) at 25.

16 See Balshaw & Goldberg (2014) at 17.

17 See Balshaw & Goldberg (2014) at 18.

18 Seate BM & Pooe RID "The relative importance of managerial competencies for predicting the perceived job performance of Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment verification practitioners" (2016) South African Journal of Human Resource Management at 697.

19 B-BBEE Codes code series 000 in GG 42496 of 31 May 2019 para 3.1.1.

20 B-BBEE Codes code series 000 in GG 42496 of 31 May 2019 para 3.1.2.

21 B-BBEE Codes code series 000 in GG 42496 of 31 May 2019 para 3.1.3

22 Horwitz FM & Jain H "An assessment of employment equity and broad-based black economic empowerment developments in South Africa" (2011) 30 Equality Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 297 at 309.

23 Horwitz FM & Jain H (2011) at 309.

24 A measured entity is defined as an entity as well as an organ of state or public entity which is subject to measurement in terms of the B-BBEE Codes.

25 It measures the effective ownership of entities by black people. See Balshaw & Goldberg (2014) at 20.

26 It measures the management control and effective governance of entities by black people. See Balshaw & Goldberg (2014) at 20.

27 It measures the extent to which a measured entity carries out initiatives designed to develop the competencies of black people. See Balshaw & Goldberg (2014) at 20.

28 It measures the extent to which entities buy goods or services from empowering suppliers with strong BEE recognition levels and the "extent to which enterprises carry out supplier development intended to accelerate the growth of black enterprises". See Balshaw & Goldberg (2014) at 20.

29 It measures the "extent to which entities implement initiatives that contribute towards socio-economic development or sector specific initiatives that promote access to the economy by black people''. See Balshaw & Goldberg (2014) at 21.

30 B-BBEE Codes code series 000 in GG 42496 of 13-05-2019 para 9.2.1.

31 B-BBEE Codes code series 000 in GG 42496 of 13-05-2019 para 9.2.1.

32 B-BBEE Codes code series 000 in GG 42496 of 13-05-2019 para 9.2.1.

33 If a measured entity has an annual total revenue of R10 million or less, it automatically qualifies as an EME. See B-BBEE Codes code series 000 in GG 42496 of 13-05-2019 para 4.1.

34 A start-up enterprise is "a recently formed or incorporated entity that has been in operation for less than one year and excludes entities that are merely a continuation of a pre-existing entity". See B-BBEE Codes GG 42496 of 13-05-2019 Interpretation and Definitions.

35 An enterprise qualifies as a QSE where it has an annual total revenue of between R10 million and R50 million. See B-BBEE Codes code series 000 in GG 42496 of 13-05-2019 para 5.1.

36 A LE is an enterprise with an annual turnover of R50 million or more. See B-BBEE Codes code series 000 in GG 42496 of 13-05-2019 para 6.1.

37 This is the Commission established in terms of the B-BBEEA.

38 B-BBEE Commission "National status and trends on broad-based black economic empowerment report" (2020) at 22.

39 See Griffin RW Management 12ed (2015) at 5.

40 Horwitz FM & Jain H (2011) at 302.

41 See Horwitz & Jain (2011) at 302.

42 Department of Labour "Commission for Employment Equity Annual Report 2013-2014" at 15; Department of Labour "Commission for Employment Equity Annual Report 2016-2017" at 12; Department of Labour "Commission for Employment Equity Annual Report 2018-2019" at 20;and Department of Labour "Commission for Employment Equity Annual Report 2019-2020" at 15.

43 Department of Labour "Commission for Employment Equity Annual Report 2013-2014" at 16. See also Department of Labour (2016-2017) at 17; Department of Labour (2018-2019) at 25; Department of Labour (2019-2020) at 19.

44 See Horwitz & Jain (2011) at 304.

45 In terms of the B-BBEE Codes, an enterprise is able to obtain points in respect of management control. Points for management control serve as an incentive to employers to place black people in management positions.

46 Seate BM & Pooe RID "The relative importance of managerial competencies for predicting the perceived job performance of broad-based black economic empowerment verification practitioners" (2016) South African Journal of Human Resource Management at 696.

47 A start-up enterprise is required to submit a QSE scorecard where such an enterprise is tendering for a contract or seeks any economic activity governed by section 10 of the Act where the value is less than R50 million and more than R10 million. Where the value of the contract is R50 million or more, a Generic scorecard should be submitted. See B-BBEE Codes Code series 000 in GG42496 of 31-05-2019 para 4.2 and para 7.6.

48 B-BBEE Codes Code series 000 in GG42496 of 31-05-2019 para 4.3.

49 B-BBEE Codes Code series 000 in GG42496 of 31-05-2019 para 4.4.2.

50 B-BBEE Codes Code series 000 in GG42496 of 31-05-2019 para 4.4.1.

51 B-BBEE Codes Code series 000 in GG42496 of 31-05-2019 para 4.5.

52 B-BBEE Codes Code series 000 in GG42496 of 31-05-2019 para 5.2.

53 B-BBEE Codes Code series 000 in GG42496 of 31-05-2019 para 5.3.2

54 B-BBEE Codes Code series 000 in GG42496 of 31-05-2019 para 5.3.1.

55 Under 51% ownership by black people.

56 B-BBEE Codes Code series 000 in GG42496 of 31-05-2019 para 5.4.

57 B-BBEE (2020) at 22.

58 B-BBEE Codes Code series 000 in GG42496 of 31-05-2019 para 3.3.2.1.

59 B-BBEE Codes Code series 000 in GG42496 of 31-05-2019 para 3.3.2.2.

60 This commission was established in 1998 to identify barriers to black economic participation.

61 Gqubele explains that this approach "entails the generation and redistribution of resources to the vast majority of the people, ranging from skills and educational training to land redistribution. Additionally [this approach stresses] the overall democratisation and transformation of institutions and organisational cultures rather than the mere inclusion of a few individuals from the previously disadvantaged communities in the ownership and management structures of the economy." See Gqubele (2016) at 11.

62 Gqubele notes that this approach "focuses BEE discourse and practice on the career mobility or advancement of black managerial, professional and business ranks". See Gqubele (2016) at 5.

63 Nkomo SM "Why white men still dominate the top echelons of South Africa's private sector" The Conversation 4 August 2015.

64 Wright EO "Understanding class towards an integrated analytical approach" (2009) 60 New Left Review 101 at 104.

65 Section 1 B-BBEEA.

66 Section 1 B-BBEEA.

67 Sibanda A "Weighing the cost of BEE fronting on best practices of corporate governance in South Africa" (2015) 29 Speculum Juris 23 at 24.

68 M'Paradzi A & Kalula E Black economic empowerment in South Africa: A critical appraisal (2007) at 41; Viking Pony Africa Pumps (Pty) Ltd t/a Tricom Africa v Hidro-Tech Systems (Pty) Ltd and Another 2011 (2) BCLR 207 (CC) at para 7.

69 See M'Paradzi & Kalula (2007) at 41.

70 Warikandwa TV & Osode PC "Regulating against business 'fronting' to advance black economic empowerment in Zimbabwe: Lessons from South Africa" (2017) Potchefstroom Electronic law Journal 1 at 17. See also CRRC E-LOCO Supply (Pty) Ltd v Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Commission & Others Case No 34701/19 para 50.

71 Swifambo Rail Leasing (Pty) Ltd v Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa 2020 (1) SA 76 (SCA) (30 November 2018).

72 See Swifambo Rail (2020) at para 25.

73 See Swifambo Rail (2020) at para 28.

74 See Swifambo Rail (2020) at para 29.

75 Peel & Others v Hamon J&C Engineering (Pty) Ltd & Others 2013(2) SA 331 (GSJ) (16 November 2012).

76 See Peel (2013) at para 17.

77 See Peel (2013) at para 19.

78 See Levenstein K "Starting a business: How can B-BBEE help me?' available at www.showme.co.za/lifestyle/starting-a-business-how-can-b-bbee-help-me/ (accessed 3 November 2021); Sibanda (2015) at 30.

79 Section 13(B)(1) B-BBEEA.

80 Section 13(B)(3)(a) B-BBEEA.

81 Section 13(F)(1)(a) B-BBEEA.

82 Section 13(F)(1)(c) B-BBEEA.

83 Section 13(F)(1)(d) B-BBEEA.

84 Section 13(F)(1)(g) B-BBEEA.

85 Section 13(G)(1) B-BBEEA.

86 Section 13(G)(2) B-BBEEA

87 Section 13(G)(3). These authorities are required to report on skills development spending as well as programmes.

88 Section 13(J)(1) B-BBEEA.

89 Section 13(J)(3) B-BBEEA.

90 Section 13(J)(4) B-BBEEA.

91 Section 13(J)(7)A B-BBEEA.

92 Section 13(J)(5) B-BBEEA.

93 Section 13(O)(1)(a)-(d) B-BBEEA.

94 Section 13(O)(2) B-BBEEA.

95 See Sibanda (2015) at 38.

96 These include verification agencies, procurement officers or other any official of an organ of state or public entity.

97 See Sibanda (2015) at 38.

98 Smith C "BEE fronting becoming more sophisticated, holding back transformation - commission" available at https://www.fin24.com/Economy/bee-fronting-becoming-more-sophisticated-holding-back-transformation-commission-20190627-2 (accessed 13 September 2021).

99 Section 13(O)(3) B-BBEA.

100 Section 13(P) B-BBEEA.

101 See Swifambo Rail (2020); Peel (2013); Esorfranki Pipelines v Popani District Municipality (40/13) (2014) ZASCA 21; Roschcon (Pty) Ltd v Anchor Auto Body Builders CC and others 2014(4) SA 319 SCA; CSARS v NWK (27/10) (2010) ZASCA 168.