Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

African Journal of Health Professions Education

On-line version ISSN 2078-5127

Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. (Online) vol.16 n.3 Pretoria Sep. 2024

https://doi.org/10.7196/ajhpe.2024.v16i3.1299

RESEARCH

Multimodal teaching and learning challenges: Perspectives of undergraduate learner nurses at a higher education institution in South Africa

L E ManamelaI; G O SumbaneII; T E MutshatshiIII; C NgoatleIV; M M M RaswesweV

IMCur [0000-0002-0484-8311]; Department of Nursing Science, School of Health Care Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Limpopo, Polokwane, South Africa

IIPhD [0000-0003-0483-1509]; Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Limpopo, Polokwane, South Africa

IIIPhD [0000-0003-1581-0041]; Department of Nursing Science, School of Health Care Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Limpopo, Polokwane, South Africa

IVPhD [0000-0001-7732-7421]; Department of Nursing Science, School of Health Care Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Limpopo, Polokwane, South Africa

VPhD [0000-0002-5077-5440]; Department of Nursing Science, School of Health Care Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Limpopo, Polokwane, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Multimodal or online learning is the use of electronic technology to deliver, support and enhance both learning and teaching. It involves communication between learner nurses and lecturers using online content. The study aims to contribute to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 4 on quality education by promoting inclusive education at tertiary institutions. The use of multimodal teaching and learning (MTL) in higher education institutions (HEI) has increased over the last decade, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic

OBJECTIVES: To explore and describe the perspectives of the undergraduate learner nurses regarding MTL challenges at the HEI, Limpopo Province, South Africa

METHODS: A qualitative, explorative, descriptive and contextual research design was used to explore and describe the perspectives of the undergraduate nurses at a HEI in Limpopo Province, South Africa. A non-probability purposive sampling method was employed to select participants. Data were collected through five focus group interviews (FGI) and analysed using Tesch's open coding data analysis method. Measures to ensure trustworthiness and ethical considerations were adhered to throughout the study

RESULTS: Study findings revealed the perspectives of the undergraduate nurses during MTL. The challenges related to connectivity issues, technological difficulties during online teaching, learning and assessment as well as the unapproved platforms used by module facilitators for online teaching

CONCLUSION: Undergraduate learner nurses expressed their perspectives regarding the challenges they experience when using MTL. Our study findings could influence educational institutions and policymakers to improve the quality of online teaching, learning and assessment by embracing innovative instructional techniques and providing teachers with ongoing training

Keywords: Challenges, multimodal teaching, multimodal learning, perspectives and undergraduate learner nurses.

Interest in multimodal teaching and learning (MTL) approaches has been increasing in South African (SA) universities since the COVID-19 pandemic. Multimodal learning is the use of electronic technology to deliver, support and enhance both learning and teaching and involves communication between learners and teachers using online content.[1] The study aims to contribute to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) on quality education by promoting inclusive education at tertiary institutions.[2] The introduction of MTL activities has posed challenges to the learning process of nursing students in general.[3] A survey involving 129 online learners showed a 29% risk of participants' minds wandering from the content offered during online learning.[4] Nevertheless, 41% of tertiary students were reported to participate satisfactorily in online learning. Previous studies have shown that tertiary students have developed a negative perspective towards online learning as they prefer a face-to-face environment of teaching and learning.[5,6]

Research shows that online learning has been linked to most students' ability to grasp and retain information at a faster rate.[7] Despite being the most promising alternative to traditional learning approaches, online learning has witnessed relatively negative perspectives from nursing students.[8] Some encountered challenges of bad network reception, difficulty in adapting to online learning methods and lack of proper resources to access the online learning platform.[9] However, Grubic et al.[5] argue that the restrictive learning conditions associated with online learning are bound to result in increased stress and downstream negative academic consequences. Some factors that often impede the adoption of MTL contexts in SA nursing schools include teachers' resistance to change, lack of adequate training, time constraints, lack of skills and competencies, teacher apprehension, lack of reward for teaching innovations, poor learner autonomy, lack of funding and inadequate resource planning.[10]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the HEI in Limpopo Province initiated the use of MTL. However, learner nurses and lecturers experienced connectivity problems, preventing them from logging onto sessions on time or at all. Network connectivity also disrupted learner nurses during tests, resulting in time loss and an inability to complete the tests. Learner nurses also complained about the structure of the test questions online, resulting in their poor performance. Although the challenges of using MTL approaches have been explored, there is little empirical research in the nursing field on the issues related to these approaches. This study aimed to identify the serious challenges related to learning theoretical and practical skills online, given that nursing education heavily relies on clinical practice. This study explores and describes the perspectives of undergraduate learner nurses regarding challenges experienced during MTL at an HEI in Limpopo Province, SA.

Methods

The study followed a qualitative, explorative and descriptive research design to explore and describe the undergraduate learner nurses' perspectives of MTL at an HEI in SA.

The study population comprised 292 undergraduate learner nurses enrolled in the 4-year Bachelor of Curationis Degree programme for the academic year 2021 at a selected HEI. Second, third and fourth-year undergraduate learner nurses were selected for their expertise and experience. Purposive sampling was employed to select participants, with those available and consenting taking part in the study.

Data collection

Five focus group interviews were conducted to collect data. One focus group involved participants from the second level, while two focus groups each comprised participants from the third and fourth levels of study. Each focus group consisted of 5 - 10 learner nurses from the second to fourth level of study. Focus group interviews were conducted in a quiet environment at the HEI. An interview guide with semi-structured questions was used during each focus group interview. The central question asked to all participants was, 'What are the challenges experienced by undergraduate learner nurses regarding MTL online activities?' A digital audiotape was used to capture all focus group interviews and field notes were taken. The focus groups lasted for approximately 47 to 92 minutes. Reflective skills were used to get clarity from the participants and further stimulate the discussion. Data collection took place over a period of 1 month and saturation was reached with the fifth focus group.

Measures to ensure trustworthiness

The Guba criteria of trustworthiness were implemented to ensure the credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability of the study. The criteria of credibility were obtained by prolonged engagement with the participants. Transferability was achieved by adhering to the purposive non-probability sampling method and the research methodological approach. Dependability was obtained through co-coding by the co-authors. Confirmability was guaranteed by using a voice recorder for the focus group interviews and writing field notes. The researchers disregarded their own feelings and only conveyed the feelings of the participants to ensure the authenticity of the study.

Data analysis

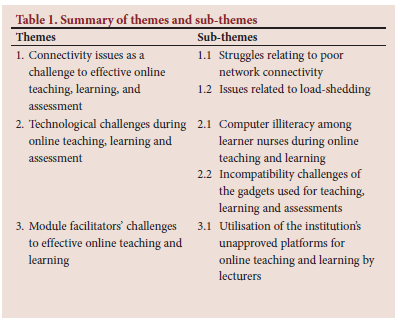

The in-depth semi-structured focus group interviews and their audio recordings were transcribed verbatim. Tesch's eight steps of open coding data analysis method were used as outlined.[12] A general reflection of the meaning of the collected data enabled the researcher to discern similarities and differences in the participants' responses. Recorded data were analysed by the researchers and an independent co-coder. A consensus was reached on the themes that emerged from the data. The three emerged themes included: i) connectivity issues as a barrier to effective online teaching and learning and assessment, ii) technological challenges during online teaching and learning and iii) module facilitators' related barriers to effective online teaching and learning.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Turfloop Research Ethics Committee to ensure adherence to ethical guidelines throughout the study (ref. no. TREC/166/2021:UG). Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the HEI. The HEI Gatekeepers granted permission to access the study's participants. Participants provided written informed consent before participating in the interview sessions. Anonymity and confidentiality were maintained throughout the study. The principles of respect for human dignity, justice and non-maleficence and beneficence were adhered to.

Results

Demographic data of focus group participants

Participants (N=34) were all undergraduate learner nurses from levels two to four of study, aged between 18 and 23 years. The five focus group interviews comprised 11 female participants from the fourth-year level, 15 female and two male participants from the third-year level and six female participants from the second-year level.

Three themes and five sub-themes emerged during data analysis. The themes and sub-themes were supported by direct quotes from the participants and are summarised in Table 1.

Theme 1: Connectivity issues as a challenge to effective online teaching and learning and assessment

It was found that learner nurses faced poor connectivity as a barrier to effective online teaching, learning and assessment. Two sub-themes emerged from this theme: struggles relating to poor network connectivity and load-shedding.

Sub-theme 1.1: Struggles relating to poor network connectivity

Students experienced poor network connectivity problems, which hampered effective online teaching, learning and assessment. This implies that when network connectivity is poor, students face challenges accessing online platforms, thereby disrupting their educational experience. This was confirmed by a participant who stated that:

'The challenges that I have experienced was poor connectivity during assessments which resulted in increased anxiety because I ended up not finishing in time'. (P2, FG 2)

Another participant reflected that:

'When writing tests, the poor network affects our duration of writing. You might find that you have less time left because of the lapse in the period that is set for writing'. (P8, FG1)

Furthermore, the findings of the study revealed that poor network connectivity affected the learner nurses' studies, as one participant affirmed that:

'As for me, where I stay there is no network; so, sometimes [I] struggle to attend or even write exams or tests'. (P3, FG5)

Sub-theme 1.2: Issues related to load-shedding

Our results show that most learner nurses are unable to complete their online tests or exams and miss classes because of load-shedding. Loadshedding refers to the practice of stopping the supply of electricity for some time because the demand is greater than the supply.[13] This highlights that the current load-shedding in SA is adversely affecting the teaching, learning and assessment of students in instructions of higher learning. One participant asserted that:

'Load-shedding affects us badly because some of our laptops are power dependable or whatever they call them, yeah, they need the power supply continuously. So, if there is no electricity, it does not work meaning that I cannot attend classes or read for exams and tests'. (P2, FG4)

Another participant reaffirmed by saying:

'The factors that contributed to problems that we face during online learning it is load-shedding, because when there is load-shedding, there is no network, and we are unable to charge our laptops or phones so that we can attend our classes". (P4, FGl)

Furthermore, another participant also disclosed that:

'The challenges that I have experienced during online learning and teaching was the load-shedding you find that you are writing exam or test online, and then load-shedding happens which means your internet connection will stop working and that will lead to your test or exam to be submitted'. (P5FG3)

Theme 2: Technological challenges during online teaching, learning and assessment

Technology refers to methods, systems, and devices that are the result of scientific knowledge being used for practical purposes.[14] The study's findings revealed that learner nurses experience technological challenges, negatively impacting their access to online teaching and learning. Sub-themes included: the students' computer illiteracy during online teaching, learning and assessments, as well as the incompatibility issues of their gadgets with the software used for teaching, learning and assessments.

Sub-theme 2.1: Computer illiteracy among learner nurses during online teaching, learning and assessments

Computer literacy and computer skills refer to the abilities required for all modern citizens to use computers to investigate, create and communicate effectively in their daily lives as well as for learning and work.[15] Our findings revealed that the majority of learner nurses in this study are not conversant with the current technological advancements, hence they struggle to access online teaching and learning. This means that loadshedding disrupts teaching, learning and assessment due to limited access to online learning resources. One participant said:

'I think factors that contributed to the challenges that I had with online assessments is the fact that some of us are from public schools, and we only started to learn computers when we got here. So now with the introduction of online, that's when we got enough time or time to actually learn how to type faster and also, we didn't have time to practice so we just had to learn in the test'. (P6, FG2)

This was supported by a participant who said:

'I also agree, I am also not technology literate, I do not have the computer skills, so it becomes a problem to type and to enter into the class. And another thing is that they teach us practical things online and you cannot teach something that is practical online. So, online learning is not working for me'. (P3, FG4)

Participant 2 further added that:

'Another thing is that it was my first-time using computers and laptops. So, I don't really know. which buttons to press so I just pressed so it was a mess. And I usually take slow to type'. (P2, FG3)

The findings of the study also revealed that the inability to type quickly has affected the learner nurses' grades, resulting in a drop compared with those obtained before online teaching and learning were introduced. This suggests that a lack of typing skills results in leaner nurses not completing their assessments, which adversely affects their grading and progression. This is evidenced by a participant who said:

'Due to online teaching my marks have dropped because when it comes to technology, I'm not knowledgeable. So, I struggle when typing because I use one finger per letter'. (P1, FG5).

Sub-theme 2.2: Incompatibility challenges of the gadgets used for teaching, learning and assessments

We also found that learner nurses were unable to connect to online teaching and learning because their devices were incompatible with the required program or software for accessing online teaching and learning. Consequently, this caused stress and frustration for most learner nurses during online teaching, learning and assessments, as one participant confirmed:

'The challenge that I face during online learning, or an online exam is that my laptop sometimes freezes while I'm writing a test or in the middle of a class'. (P4, FG1)

Another participant stated:

'The challenge which I face is the fact that while I'm writing using responders, the system may shut down and time keeps on ticking while the system is down'. (P8, FG1)

One participant alluded that:

'We were presenting in class, but when it was my turn, I had to open my mic, but then it started doing this yellow round thing to show it's loading nonstop and then I was kicked out of the class a couple of times'. (P3, FG3)

Theme 3: Module facilitators' related barriers to effective online teaching and learning

The final theme concerned barriers encountered by module facilitators, which impact the effectiveness of online teaching and learning. Hence, the use of unapproved platforms (by the HEI) for online teaching and learning by lecturers emerged as a sub-theme.

Sub-theme 3.1: Use of unapproved platforms for online teaching and learning by lecturers

The participants indicated that some lecturers were using platforms that were unapproved by the institution for online teaching and learning, which negatively impacted their learning. This suggests that lecturers resorted to using platforms they are familiar and comfortable with at the expense of learner nurses' benefits. A participant revealed that:

'Okay, sometimes when our lecturers are teaching, they are not using the prescribed platforms for teaching. Maybe instead of using Blackboard Collaborate, you find that the lecturer is using Google Meet or Zoom, and we are not orientated to such Apps and everything and those Apps do not have a recording of the sessions so that if maybe you had network problems during class you can also go back and listen again. So, immediately when the class is over, it means it is done whether you had network problems or what, it means that you, did not attend the class. So, it contributes negatively to our learning since like you missed the content that was being taught in class, which will end up making you not understanding the things that were done if you are to be assessed'. (P1FG4)

Furthermore, another participant supported that, stating:

'The challenges I have experienced is that of lecturers who used other platforms for learning such as zoom and not blackboard. Zoom classes or google meet classes consume a lot of data and some of us where we stay, do not have routers for Wi-Fi connectivity'. (P3FG2)

Discussion

Undergraduate learner nurses in this study reported challenges hindering the effectiveness of online teaching, learning and assessment at the selected HEI. These challenges included connectivity, technological problems and facilitation difficulties. According to the participants, the primary challenge to using the online teaching and learning platform is connectivity problems. A previous study reported that temporary energy distribution cuts were the cause of the connectivity problems.[16] Currently, SA is experiencing a phenomenon known as 'load-shedding', which involves the purposeful cutting off of electricity in parts of the power distribution system to prevent system failure when demand exceeds capacity.[13] This is due to insufficient electricity produced by the country's power plants. When this occurs, it 'sheds the load' by ceasing to supply power to specific grid segments to release strain on the power plant.[13]

During load-shedding, online platforms were interrupted due to inadequate network access and owners of laptops that need to be plugged in to function were affected. Besides load-shedding, the chosen HEI is in a remote area where network connectivity is a constant issue. This results in the cancellation or rescheduling of online classes or tests, which affects the smooth running of the programme. Although the university does have a backup system, it is limited to students residing on campus. Despite the backup system, network connectivity remains inadequate even when attempts are made to reconnect. Another study reported similar challenges, revealing that unreliable internet connectivity with frequent abrupt signal loss in rural areas affects learner nurses' studies.[17]

Most learner nurses were found to be digitally illiterate, posing another difficulty as it prevented them from efficiently completing online assessments. They received low marks on their assessments owing to these technological difficulties, which led to an unfavourable perception of online teaching, learning and assessment.[15,16] Therefore, there is a need to develop nursing students' computer skills to improve their proficiency in navigating online teaching and learning.[19]

Study findings also identified ongoing incompatibility challenges with the devices needed for teaching, learning and assessment. Learner nurses also mentioned that their cell phone specifications were incompatible with some of the online teaching and learning platforms. The findings are corroborated by those of another study that revealed that when learner devices are not compatible with the online platform in use, learners are unable to download the application, hence teaching and learning are compromised.[20] Other incompatibility challenges were related to financial constraints among learner nurses engaging in online teaching and learning.[21] Furthermore, some platforms used by lecturers, such as Zoom, require a lot of data bundles, which depletes data quickly and makes it costly for learner nurses to access recordings of previous sessions.[22,23] This is supported by another study's findings, which indicate that the use of various online teaching platforms by lecturers, especially unapproved ones, negatively impacted the students.[24]

Study limitations

The study was limited to a single HEI offering a 4-year Bachelor of Curationis Degree programme in the Limpopo Province, SA. Therefore, findings may not be representative of all learner students in SA.

Conclusion

This study reports the perspectives of HEI undergraduate learner nurses on the challenges they experience with MTL. The findings confirm that MTL is posing difficulties for undergraduate learner nurses at this specific HEI. Connectivity issues due to poor network and load-shedding were the main challenge affecting the students' educational experience. Other challenges included technological illiteracy, incompatibility of devices and lecturers using unfamiliar or unapproved platforms for online teaching and learning. To ensure that MTL meets users' needs effectively, special training courses should be offered for both lecturers and learner nurses on accessing and using virtual education, along with recommended platforms. In addition, they should be provided with technical support from a central place to assist during lessons and assessments. In the event of unforeseen circumstances like load-shedding, a persistent issue in SA, the institutional Wi-Fi should be powered by backup systems to ensure continuous internet connectivity. We also recommend using institutional suggested online teaching and learning platforms, as they are familiar to learner nurses and easily accessible on their devices.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. The authors owe their deepest gratitude to the 2nd, 3rd and 4th-year learner nurses from the HEI in Limpopo Province, who generously shared their personal experiences to make this study possible. We further acknowledge the efforts of final-year nursing students of the HEI in the Limpopo Province, who assisted with the data collection.

Author contributions. All authors assisted in the initial conceptualisation, refinement and finalisation of the manuscript for publication.

Funding. None.

Data availability statement. The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Langegârd U, Kiani K, Nielsen, SJ, Svensson PA. Nursing students' experiences of a pedagogical transition from campus learning to distance learning using digital tools. BMC Nurs 2021;20(1):1-10. [ Links ]

2. Ferguson T, Roofe CG. SDG 4 in higher education: Challenges and opportunities. Int J Sustainability in Higher Education 2020;21(5):959-975. [ Links ]

3. Aboagye E, Yawson JA, Appiah KN. COVID-19 and E-learning: The challenges of students in tertiary institutions. Soc Educ Res 2021:1-8. https://doi.org/10.37256/ser.212021422 [ Links ]

4. Baticulon RE, Sy JJ, Alberto NRI, et al. Barriers to online learning in the time of COVID-19 : A national survey of medical students in the Philippines. Med Scie Educ 2021;31:615-626. [ Links ]

5. Grubic N, Badovinac S, Johri AM. Student mental health in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for further research and immediate solutions. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2020:66(5):517-518. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020925108 [ Links ]

6. Archer A, Newfield D. Challenges and opportunities of multimodal approaches to education in South Africa. Multimodal Approaches to Research and Pedagogy 2014:19-34. [ Links ]

7. Kotera Y, Ting SH, Neary S. Mental health of Malaysian university students: UK comparison, and relationship between negative mental health attitudes, self-compassion, and resilience. Higher Educ 2021;81(2):403-419. [ Links ]

8. Haipinge E, Olivier J. Paving the way towards success in terms of the 4th industrial revolution: The affordances of multimodal multiliteracies. The Role of Open, Distance and eLearning in the 4th Industrial Revolution (4IR). 2019;39. [ Links ]

9. Chinn J, Tewari KS. Multimodality screening and prevention of cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: A collaborative model. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2020;32(1):28-35. [ Links ]

10. Cooshna-Naik D. Undergraduate students' experiences with learning with digital multimodal texts (Doctoral dissertation) University of KwaZulu-Natal. 2018. [ Links ]

11. Guba EG. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Educ Tech Res Dev 1981;29(2):75-91. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02766777 [ Links ]

12. Botman Y, Greeff M, Mulaudzi FM, Wright SCD. Research in health sciences. South Africa: Heinemann. 2015:251-254. [ Links ]

13. Harrison D. What is load shedding and who decides whose power is cut when there's not enough electricity. 2019. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-12-06/what-is-load-shedding-and-how-does-itwork/11650096. [ Links ]

14. Dictionary CE. Concept definition and meaning. Collins English Dictionary 2018. [ Links ]

15. Fraillon J, Ainley J, Schulz W, Duckworth D, Friedman T. Computer and information literacy framework. In IEA International Computer and Information Literacy Study Assessment Framework. Springer, Cham. 2019:13-23. [ Links ]

16. Kebritchi M, Lipschuetz A, Santiague L. Issues and challenges for teaching successful online courses in higher education: A literature review. J Educ Techn Syst 2017;46(1):4-29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239516661713 [ Links ]

17. Hodges CB, Moore S, Lockee BB, Trust T, Bond MA. The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. 2020. [ Links ]

18. Coopasami M, Knight S, Pete M. 'E-learning readiness amongst nursing students at the Durban University of Technology, Health SA Gesondheid 2018;22:300-306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hsag.2017.04.003 [ Links ]

19. Sharin AN. E-learning during Covid-19: A review of literature. J Pengajian Media Malaysia 2021;23(1):15-28. [ Links ]

20. Khan S, Khan RA. Online assessments: Exploring perspectives of university students. Educ Inform Tech 2019;24(1):661-677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-018-9797-0 [ Links ]

21. Rahiem MD. The emergency remote learning experience of university students in Indonesia amidst the COVID-19 crisis. Int J Learning Teach Educ Res 2020;19(6):1-26. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.19.6.1 [ Links ]

22. Van Lancker W, Parolin Z. COVID-19 , school closures, and child poverty: A social crisis in the making. Lancet Pub Health 2020;5(5):243-244. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30084-0 [ Links ]

23. Rapanta C, Botturi L, Goodyear P, Guàrdia L, Koole M. Online university teaching during and after the Covid-19 crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Post-dig Sci Educ 2020;2(3):923-945. [ Links ]

24. Bisht RK, Jasola S, Bisht IP. Acceptability and challenges of online higher education in the era of Covid-19: A study of students' perspective. Asian Educ Dev Studies 2020. https://doi.org/10.1108/AEDS-05-2020-0119 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

L E Manamela

ledile.manamela@ul.ac.za

Submitted 20 July 2023

Accepted 15 April 2024