Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Psychiatry

On-line version ISSN 2078-6786Print version ISSN 1608-9685

S. Afr. j. psyc. vol.21 n.2 Pretoria May. 2015

https://doi.org/10.7196/SAJP.662

ARTICLE

Extent of alcohol use and mental health (depressive and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms) in undergraduate university students from 26 low-, middle- and high-income countries

K PeltzerI; S PengpidII

IPhD;ASEAN Institute for Health Development, Mahidol University, Salaya, Phutthamonthon, Nakhonpathom, Thailand; Department of Psychology, University of Limpopo, Turfloop Campus, Sovenga, South Africa; HIV/AIDS/STIs and TB (HAST), Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria, South Africa

IIDrPh; ASEAN Institute for Health Development, Mahidol University, Salaya, Phutthamonthon, Nakhonpathom, Thailand; Department of Research & Innovation, University of Limpopo, Turfloop Campus, Sovenga, South Africa

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: To estimate if there is a non-linear association between varying levels of alcohol use and poor mental health (depressive and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms) in university students from low-, middle- and high-income countries.

METHODS: Using anonymous questionnaires, data were collected from 19 238 undergraduate university students (mean age 20.8; standard deviation (SD) 2.8) from 27 universities in 26 countries across Asia, Africa and the Americas. Alcohol use was assessed in terms of number of drinks in the past 2 weeks and number of drinks per episode, and measures of depression and PTSD symptoms were administered.

RESULTS: The proportion of students with elevated depression scores was 12.3%, 16.9%, and 11.5% for non-drinkers, moderate drinkers, and heavy drinkers, respectively, while the proportion of students with high PTSD symptoms was 20.6%, 20.4% and 23.1% for non-drinkers, moderate drinkers, and heavy drinkers, respectively. Logistic regression found that non-drinkers and heavy drinkers had a lower odds than moderate drinkers to have severe depression, after adjusting for sociodemographic variables, social support and subjective health status. Further, heavy, more frequent drinkers and more frequent binge drinkers had a higher odds to have elevated PTSD symptoms than moderate and non-drinkers, after adjusting for sociodemographic variables, social support and subjective health status.

CONCLUSION: The results suggest a reverse U-shaped association between recent alcohol use volume and frequency and depressive symptoms (unlike that previously identified), and a J-shaped association between binge drinking frequency and depressive symptoms and alcohol use and PTSD symptoms.

Some evidence has been advanced that high alcohol use is associated with poor mental health (depression and anxiety),[1,2] while light or moderate alcohol use is protective of poor mental health.[3,4] Various authors report a U-shaped relationship between alcohol consumption and mood and anxiety disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), i.e. better mental health for light to moderate drinking compared with abstainers or excessive drinkers.[3-6] Kushner et al.[7]propose that anxiety disorder and alcohol disorder can both serve to initiate the other. Bellos et al.[3] note that 'the potentially positive effect of light or moderate alcohol consumption in physical health (as opposed to the harmful effect at higher doses) has not been adequately explored in relation to mental health.' Previous studies have mainly been based on samples in industrialised or high-income countries, while less is known about this relationship in study samples in developing countries.

The aim of this study was to assess the association between varying levels of alcohol use and poor mental health (depression and PTSD symptoms) in university students from 26 low-, middle- and high-income countries in Africa, Asia and the Americas.

Methods

Sample and procedure

This cross-sectional study was carried out with a network of collaborators in participating countries (see Acknowledgments). The anonymous, self-administered questionnaire used for data collection was developed in English, then translated and back-translated into languages (Arabic, Bahasa, French, Lao, Russian, Spanish, Thai, Turkish) of the participating countries. The study was initiated through personal academic contacts of the principal investigators. These collaborators arranged for data to be collected from intended 400 male and 400 female undergraduate university students aged 16 -30 years by trained research assistants in 2013 in one or two universities in their respective countries. The sample size was calculated by using Epi-Info Version 7.1 (CDC). For the population survey, the expected frequency of 50%, design effect 1, confidence limited 5%, cluster 1, the population size was approximately 20 000 students per university. For a 99% confidence interval (CI), we required a minimum sample size of 644. This study examines behaviours in male and female students; thus the sample size is split into two groups of 322 each. To prevent loss or uncompleted data, the sample size was increased to 800 (400 male, 400 female). The universities involved were located in the capital cities or other major cities in the participating countries. Research assistants working in the participating universities asked classes of undergraduate students to complete the questionnaire at the end of a teaching class. In each study country, undergraduate students were surveyed in classrooms, selected through a stratified random sample procedure. A university department formed a cluster and was used as a primary sampling unit. One department was randomly selected from each faculty. For each selected department, undergraduate courses offered by the department were randomly ordered. The students who completed the survey varied in terms of the number of years they had attended the university. A variety of majors were involved, including education, humanities and arts, social sciences, business and law, science, engineering, manufacturing and construction, agriculture, health and welfare, and services. Informed consent was obtained from participating students, and the study was conducted in 2013. Participation rates were over 90% in most countries. The number of participants in each country was as follows: Bangladesh (788), Barbados (564), Cameroon (627), China (1112), Columbia (816), Egypt (801), Grenada (423), India (800), Indonesia (750), Ivory Coast (754), Jamaica (740), Kyrgyzstan (835), Laos (806), Madagascar (776), Mauritius (421), Namibia (490), Nigeria (723), Pakistan (813), Philippines (782), Russia (789), Singapore (888), South Africa (742), Thailand (858), Tunisia (774), Turkey (800) and Venezuela (564). Ethics approvals were obtained from institutional review boards from all participating institutions.

Measures

Alcohol use. Participants were asked about drinking alcohol, including beer, wine, spirits and any other alcoholic drink. Those who responded that they drink alcohol were asked: 'On how many days over the past 2 weeks (14 days) did you have a drink?' and 'On the days that you did drink, how many drinks did you have on average?'[8] Drinking volume in a typical day was then classified into three groups: non-drinkers, moderate drinkers (men <4 drinks and women <3 drinks at a sitting), and heavy drinkers (men >5 drinks and women >4 drinks at a sitting).[4] The classification of overall number of drinks in the past 2 weeks was into four groups: none, 1 - 4 drinks, 5 - 13 drinks, and 14 or more drinks.[4] In addition, students were asked: 'How often do you have (for men) five or more and (for women) four or more drinks on one occasion?' Response options ranged from 0 = never, 1 = less than monthly, 2 = monthly, 3 = weekly to 4 = daily or almost daily.[9]

Centres for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). We assessed depressive symptoms using the 10-item version of the CES-D.[10] Scoring is classified from 0 - 9 as having a mild level of depressive symptoms, 10 - 14 as moderate depressive symptoms, and 15 representing severe depressive symptoms.[11] The Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient of this 10-item scale was 0.74 in this study.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Breslau's 7-item screener was used to identify PTSD symptoms in the past month.[12] Items asked whether the respondent had experienced difficulties related to a traumatic experience (e.g. 'Did you begin to feel more isolated and distant from other people?'). Consistent with epidemiological evidence, participants who answered affirmatively to at least four of the questions were considered to have a positive screen for PTSD.[12] The Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient of this 7-item scale was 0.75 in this study.

Subjective general health status was assessed with the question, 'In general, would you say your health is...?' (rated from 1 = excellent to 5 = poor).[8]

Social support. Three items from the Social Support Questionnaire were utilised to assess perceived tangible and emotional social support.[13] Cronbach alpha for this social support index was 0.95.

Sociodemographic questions included age, gender and residential status; socioeconomic background was assessed by rating their family background as wealthy (within the highest 25% in their country in terms of wealth), quite well-off (within the 50 - 75% range), not very well-off (within the 25 - 50% range), or quite poor (within the lowest 25% in their country in terms ofwealth).[8] In addition, study countries were ranked according to the World Bank country income classifications, into low-income, lower-middle-income, upper-middle-income and high-income country.[14]

Data analysis

The data were analysed using STATA 11.00 (StatCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics and tests for gender differences were used to describe the sample. Alcohol use variation was analysed in terms of the number of drinks used in a single session (non-drinker, moderate and heavy drinker), and the total number of drinks in the past 2 weeks (none, 1 - 4, 5 - 13, and 14 or more)[4] and binge drinking frequency (never, <monthly, monthly, weekly, daily or almost daily). Logistic regression was used to assess the association betweenalcohol use and severe depressive symptoms (>15) and PTSD symptoms (>4), separately. This model was adjusted for age, gender, wealth, residential status, country income level, social support and subjective health status; p<0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Sample characteristics

The sample with complete alcohol use data included 19 238 university students, 8 034 (41.9%) male and 11 145 females (58.1%).

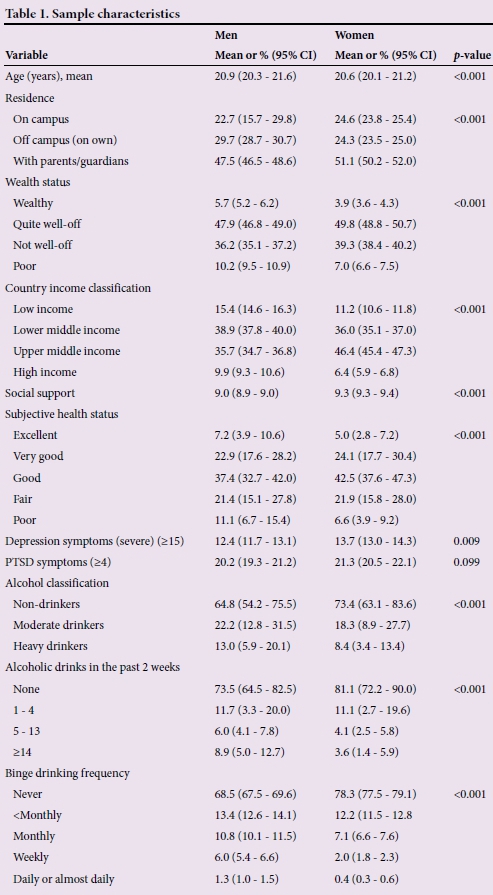

There were gender differences in sociodemo-graphic variables as well as health variables. Male students had a poorer subjective health, were more frequently moderate and heavy drinkers, had more alcoholic drinks in the past 2 weeks and were more frequent binge drinkers than female students, while female students reported more frequently depressive symptoms than male students (Table 1).

Varying levels of alcohol use and depressive symptoms

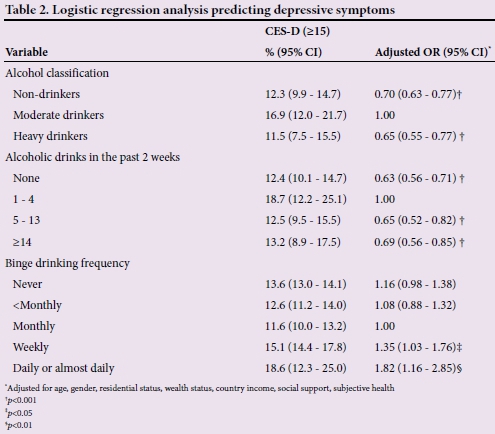

More moderate drinkers than non-drinkers and heavy drinkers had depression symptoms indicating severe depression. Logistic regression found that non-drinkers and heavy drinkers had lower odds than moderate drinkers to have severe depression, after adjusting for age, gender, wealth, residential status, country income level and subjective health status.

Regarding the number of alcoholic drinks consumed in the past 2 weeks, more students who drank 1 - 4 drinks had depression symptoms indicating severe depression than those who drank none or >4 drinks in the past 2 weeks. Likewise, logistic regression found that students having 1 - 4 drinks in the past 2 weeks had higher odds to have elevated levels of depression than students who did not drink or drank >4 drinks in the past 2 weeks. However, there was a positive association with the frequency of binge-drinking and depressive symptoms after adjusting for sociodemographic variables and subjective health status (Table 2).

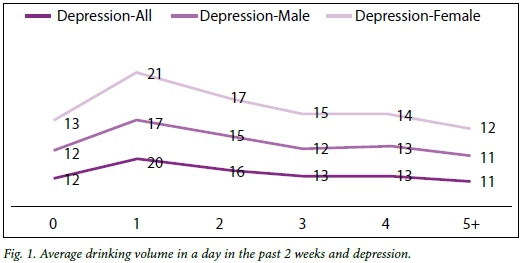

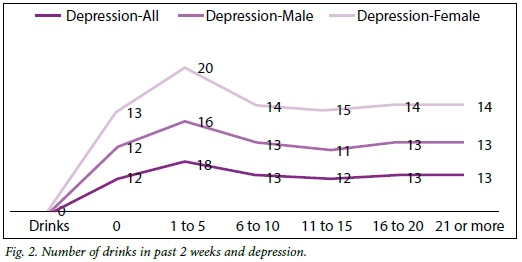

In Figs 1, 2 and 3 we explore the shape of the relationship between different measures and levels of alcohol use (including abstainers) in relation to depressive symptoms. Average drinking volume in a day was grouped into the levels of 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 or >5 drinks. The number of drinks in the past 2 weeks was grouped into the levels of 0, 1 - 5, 6 - 10, 11 - 15, 16 - 20, and >21, and the frequency of binge drinking was grouped into the levels of never, less than monthly, monthly, weekly, and daily or almost daily. There was some evidence for a reverse U-shaped curve for Fig. 1 (average drinking volume in a day) and Fig. 2 (number of drinks in the past 2 weeks), while in Fig. 3 (frequency of binge drinking) a J-shaped curve was found.

Varying levels of alcohol use and PTSD symptoms

Fewer moderate drinkers and non-drinkers had elevated PTSD symptoms than heavy drinkers. Logistic regression analysis indicates that heavy drinkers had higher odds to have elevated PTSD symptoms than moderate drinkers, after adjusting for age, gender, wealth, residential status, country income level and subjective health status.

Regarding the number of alcoholic drinks consumed in the past 2 weeks, fewer students who had 1 - 4 drinks had elevated PTSD symptoms than those who drank 5 - 13 and 14 or more drinks. In logistic regression students who drank 14 or more drinks in the past 2 weeks were more likely to have elevated levels of PTSD symptoms than those who drank 1 - 4 drinks or none, after adjusting for age, gender, wealth, residential status, country income level and subjective health status. Further, there was a positive association between weekly binge drinking and PTSD symptoms after adjusting for sociodemographic variables and subjective health status (Table 3).

Discussion

This study among a large sample of university students in low-, middle- and high-income countries across Africa, Asia and the Americas concurs with previous studies,[3,4] which found a non-linear relationship between poor mental health (depression and PTSD symptoms) and different levels of alcohol use. In contrast to some previous research,[3-6] this study found a reverse U-shape relationship between average drinking volume, number of drinks in the past 2 weeks and depressive symptoms, while a J-shape relationship was found between frequency of binge drinking and depressive symptoms, and between average drinking volume, number of drinks in the past 2 weeks, frequency of binge drinking and PTSD symptoms. The observed associations were not significantly influenced by a number of potentially confounding variables, including sociodemographic variables, social support and subjective health status. Regarding the findings in relation to depression, it appears there is a similarity to what Graham et al.[15] found, that depression is mainly related to consuming larger amounts of alcohol per occasion, and less related to the volume and frequency of drinking. It is unclear why a non-linear relationship between alcohol use and poor mental health exists. In particular, why in the recent (past 2 weeks) alcohol assessment light alcohol use was associated with higher depressive symptoms than abstinent or heavy alcohol use. It is possible that light alcohol use may lead to depressive symptoms, whereas non-drinking and heavier or more frequent drinking have a protective effect. Regarding the other finding, it is possible that students with depressive symptoms cope by means of frequent binge drinking. Further, having PTSD symptoms may lead to increased alcohol use.[5] We did not find gender differences in the relationship curve between alcohol use levels and depressive and PTSD symptoms, as found in some other studies.[16] This study had a high proportion of non-drinkers, much higher than in previous studies in university students or young adults, mainly from industrialised or high-income countries.[4,17] It is possible that because of the very high proportion of non-drinkers, the relationship with depressive symptoms became inflated.

Study strength and limitations

The study has strength in terms of having used standard measures ofalcohol use, depression and PTSD symptoms with samples of comparable undergraduate students in each country. This study also had several limitations. The study was cross-sectional, so causal conclusions cannot be drawn. The investigation was carried out with students from one or two universities in each country, and inclusion of other centres could have resulted in different results. University students are not representative of young adults in general, and the alcohol use levels, depression and PTSD symptoms may be different in other sectors of the population. A further limitation of the study was that all information collected in the study was based on self-reporting. It is possible that certain behaviours were under- or over-reported. We also did not assess lifetime and former alcohol use patterns in this young study population (mean age 20.8 years). However, a study by Alati et al.[18] found that previous drinkers who become abstainers do not have a higher risk of depression or anxiety symptoms compared with those who have always abstained.

Conclusion

Light recent alcohol use (volume and frequency) may have an effect on depressive symptoms in young adults relative to abstinence and heavy or frequent alcohol use. Moderate frequency of binge-drinking may have no effect on depression symptoms in young adults relative to abstinence and more frequent binge-drinking. Further, abstinent, light or moderate alcohol use may have no effect on PTSD symptoms in young adults relative to more frequent alcohol use (volume and frequency) and frequent binge-drinking.

Acknowledgements. Partial funding for this study was provided by the South African Department of Higher Education. The following colleagues participated in this student health survey and contributed to data collection (locations of universities in parentheses): Bangladesh: Gias Uddin Ahsan (Dhaka); Barbados: T Alafia Samuels (Bridgetown); Cameroon: Jacques Philippe Tsala Tsala (Yaounde); China: Tony Yung, Xiaoyan Xu (Hong Kong and Chengdu); Colombia: Carolina Mantilla (Pamplona); Egypt: Alaa Abou-Zeid (Cairo); Grenada: Omowale Amuleru-Marshall (St. George); India: Krishna Mohan (Visakhapatnam); Indonesia: Indri Hapsari Susilowati (Jakarta); Ivory Coast: Issaka Tiembre (Abidjan); Kyrgyzstan: Erkin M Mirrakhimov (Bishkek); Laos: Vanphanom Sychareun (Vientiane); Madagascar: Onya H Rahamefy (Antananarivo); Mauritius: Hemant Kumar Kassean (Réduit, Moka); Namibia: Pempelani Mufune (Windhoek); Nigeria: Solu Olowu (Ile-Ife); Pakistan: Rehana Reman (Karachi); Philippines: Alice Ferrer (Miagao); Russia: Alexander Gasparishvili (Moscow); Singapore: Mee Lian Wong (Singapore); Thailand: Tawatchai Apidechkul (Chiang Rai); Tunisia: Hajer Aounallah-Skhiri (Tunis); Turkey: Neslihan Keser Özcan (Istanbul); Venezuela: Yajaira M Bastardo (Caracas).

References

1. Peltzer K. Depressive symptoms in relation to alcohol and tobacco use in South African university students. Psychol Rep 2003;92:1097-1098. [ Links ]

2. Sareen J, McWilliams L, Cox B, Stein MB. Does a U-shaped relationship exist between alcohol use and DSM-III-R mood and anxiety disorders? J Affect Disord 2004;82:113-118. [ Links ]

3. Bellos S, Skapinakis P, Rai D, et al. Cross-cultural patterns of the association between varying levels of alcohol consumption and the common mental disorders of depression and anxiety: Secondary analysis of the WHO Collaborative Study on Psychological Problems in General Health Care. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;133:825-831. [ Links ]

4. O'Donnell K, Wardle J, Dantzer C, Steptoe A. Alcohol consumption and symptoms of depression in young adults from 20 countries. J Stud Alcohol 2006;67:837-840. [ Links ]

5. McFarlane AC, Browne D, Bryant RA, et al. A longitudinal analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of posttraumatic symptoms. J Affect Disord 2009;118:166-172. [ Links ]

6. Rodgers B, Korten AE, Jorm AF, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Henderson AS. Non-linear relationships in associations of depression and anxiety with alcohol use. Psychol Med 2000;30:421-432. [ Links ]

7. Kushner MG, Abrams K, Borchardt C. The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: A review of major perspectives and findings. Clin Psychol Rev 2000;20:149-171. [ Links ]

8. Wardle J, Steptoe A. The European Health and Behaviour Survey: Rationale, methods and initial results from the United Kingdom. Soc Sci Med 1991;33: 925-936. [ Links ]

9. Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001. [ Links ]

10. Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med 1994;10:77-84. [ Links ]

11. Mulrow CD, Williams JW Jr, Gerety MB, et al. Case-finding instruments for depression in primary care settings. Ann Intern Med 1995;122: 913-921. [http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-122-12-199506150-00004] [ Links ]

12. Kimerling R, Ouimette P, Prins A, et al. Brief report: Utility of a short screening scale for DSM-IV PTSD in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:65-67. [ Links ]

13. Brock D, Sarason I, Sarason B, Pierce G. Simultaneous assessment of perceived global and relationship-specific support. J Soc Pers Relationships 1996;13:143-152. [ Links ]

14. World Bank, New Country Classifications, 2013. http://data.worldbank.org/news/new-country-classifications (accessed 12 June 2014). [ Links ]

15. Graham K, Massak A, Demers A, Rehm J. Does the association between alcohol consumption and depression depend on how they are measured? Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2007;31:78-88. [ Links ]

16. Zhan W, Shaboltas AV, Skochilov RV, Kozlov AP, Krasnoselskikh TV, Abdala N. Gender differences in the relationship between alcohol use and depressive symptoms in St. Petersburg, Russia. J Addict Res Ther 2012;3(2). [http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2155-6105.1000124] [ Links ]

17. Paschall MJ, Freisthler B, Lipton RI. Moderate alcohol use and depression in young adults: findings from a national longitudinal study. Am J Public Health 2005;95:453-457. [ Links ]

18. Alati R, Lawlor DA, Najman JM. Is there really a 'J-shaped' curve in the association between alcohol consumption and symptoms of depression and anxiety? Findings from the Mater-University Study of Pregnancy and its outcomes. Addiction 2005;100:643-651. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

K Peltzer

kpeltzer@hsrc.ac.za