Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Lexikos

On-line version ISSN 2224-0039Print version ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.33 Stellenbosch 2023

https://doi.org/10.5788/33-1-1816

ARTICLES

The Language of Ethnic Conflict in English Online Lexicography: Ethnophaulisms in "powered by Oxford" Lexico.com

Die taal van etniese konflik in die Engelse aanlyn leksikogra-fie: Etnofaulisme in die "Oxford-gedrewe" Lexico.com

Silvia Pettini

Department of Foreign Languages, Literatures and Cultures, Roma Tre University, Rome, Italy (silvia.pettini@uniroma3.it)

ABSTRACT

This article aims to explore the relationship between the language of ethnic conflict (Allen 1983; Palmore 1962) and English online lexicography in the present cultural moment. Given the influence of the Internet on dictionary consulting (Béjoint 2016; Jackson 2017) and the alarming increase of racism and xenophobia, especially online, at the global level in this digital age (see Gagliardone et al. 2015), this article presents a pilot study examining the treatment of "ethnophaulisms" (Roback 1944), commonly referred to as ethnic or racial slurs, in the "powered by Oxford" dictionary content, which is licensed for use to technology giants like Google, Microsoft, and Apple by Oxford University Press (Ferrett and Dollinger 2021; Pettini 2021). In particular, the analysis focuses on the online edition of the Oxford Dictionary of English, as hosted on the "powered by Oxford" Lexico.com website. Preliminary findings show how this free online dictionary mirrors the taboo and discriminatory nature of ethnophaulisms and warns the Internet user against the derogatory and offensive power of these words.

Keywords: english lexicography, online dictionaries, linguistic racism, xenophobia, hate speech, ethnic slurs, ethnophaulisms, oxford dictionary of english, lexico.com

OPSOMMING

In hierdie artikel word gepoog om die verhouding tussen die taal van etniese konflik (Allen 1983; Palmore 1962) en die Engelse aan-lyn leksikografie soos op hierdie kulturele moment te ondersoek. Gegewe die invloed van die internet op die raadpleging van woordeboeke (Béjoint 2016; Jackson 2017) en die, veral aanlyn, kommer-wekkende toename van rassistiese en xenofobiese gevalle op globale vlak in hierdie digitale era (sien Gagliardone et al. 2015), word daar in hierdie artikel 'n loodsstudie aangebied waarin die hantering van etnofaulisme (Roback 1944), waarna meestal verwys word as etniese of rassistiese beledigings, in die "Oxford-gedrewe" woordeboekinhoud, wat deur Oxford University Press gelisensieer is vir gebruik deur tegnologiereuse soos Google, Microsoft, en Apple (Ferrett en Dollinger 2021; Pettini 2021), ondersoek word. Die ontleding fokus spesifiek op die aanlyn weergawe van die Oxford Dictionary of English, soos beskikbaar op die "Oxford-gedrewe" Lexico.com-webtuiste. Voorlopige resultate dui daarop dat hierdie gratis aanlyn woordeboek die taboe- en diskriminerende aard van etno-faulisme weerspieël en die internetgebruiker teen die neerhalende en aanstootlike effek van hierdie woorde waarsku.

Sleutelwoorde: engelse leksikografie, aanlyn woordeboeke, linguistiese rassisme, xenofobie, haatspraak, etniese beledigings, etnofaulisme, oxford dictionary of english, lexico.com

1. Introduction

In order to investigate the language of ethnic conflict in English online lexicography, this article presents the preliminary findings of a wider ongoing study on the treatment of ethnophaulisms, commonly referred to as ethnic or racial slurs, in the so-called "powered by Oxford" dictionary content.

As Ferrett and Dollinger (2021) explain, "powered by Oxford" is the content Oxford University Press (OUP hereafter) license for use to technology giants like Google, Yahoo, and Bing, as regards search engines, and to the pre-installed dictionaries on dominant operating systems like Microsoft and Apple. This means, for example, that due to OUP's partnership with Google, search operators like 'define or definition' or 'what does ... mean' in Google's search engine bring up and explicitly cite Oxford definitions first, because Google English dictionary is "powered by Oxford" (Oxford Languages 2023). Moreover, "powered by Oxford" is also the dictionary website scrutinized in this paper, namely Lexico.com. Previously known as Oxford Dictionaries Online, Lexico.com was OUP's domain for the free online version of the Oxford Dictionary of English from June 2019 to August 26, 2022, the day on which the Lexico.com website was closed and redirected to Dictionary.com, the original website operator (wikipedia 2023a). However, as users can learn when reading the 'About' section of Dictionary.com (2023), the online edition of the Oxford Dictionary of English was not actually moved to this website, since "Dictionary.com's main, proprietary source is the Random House Unabridged Dictionary".

Going back to the present case study, it is easy to understand that due to their partnerships, OUP has a remarkable market advantage because "powered by Oxford" dictionary content is extremely widespread, and this cannot but influence the way Internet users deal with language issues in this information age. As an example, Google alone accounts for more than 90% of the search engine market share worldwide (Statcounter 2023) and it is the most visited website in the world (Semrush 2023).

The rationale behind this study lies exactly in the dominant market position of "powered by Oxford" content, in connection with two typical phenomena of this digital age.

The first one is the remarkable influence of the Internet on dictionary consulting. Indeed, as many authors have highlighted (cf. Béjoint 2016; Jackson 2017; Lew and De Schryver 2014; Lorentzen and Theilgaard 2012; Müller-Spitzer and Koplenig 2014), there is a clear and increasing tendency among Internet users to search for lexical information via general search engines, that is to say, most current users tend to google their language issues (Jackson 2017: 540).

The second phenomenon linked to this study rationale is the alarming increase of xenophobia, racism, and intolerance around the world, which, linguistically, translates into a proliferation of cases of hate speech, especially online, the majority of which target individuals based on ethnicity and nationality (Gagliardone et al. 2015: 13). Although it is beyond the scope of this article, it seems worth briefly mentioning that hate speech is used here as an umbrella term and includes pejorative, offensive or discriminatory uses of language with reference to a person or a group based on identity factors like ethnicity, nationality, colour, and descent.

For these reasons, the free and almost ubiquitous "powered by Oxford" dictionary content represents a good case in point to analyze the treatment of ethnic slurs or verbal expressions of intercultural or ethnic conflict, that is "eth-nophaulisms" (Roback 1944), in English online lexicography with a focus on the perspective of the general user of the Internet. In other words, this study aims to answer the following research question: what does a general user of the Internet learn about the offensiveness of ethnophaulisms when looking them up on major online platforms? Since the latter are "powered by Oxford", the objective is to examine whether and how this free and pervasive online dictionary content (a) reflects the taboo nature of ethnophaulisms, (b) warns Internet users against the discriminatory power of these words, and, thus, (c) signals their hurtful nature.

To address these questions, this article explores and contextualizes the concept of ethnophaulism in the light of the relation between language, dictionaries, and society, with special attention to the increasing taboo and politically incorrect status of these expressions, which has inevitably affected both the theory and the practice of English monolingual lexicography. This critical perspective indeed characterizes a long and productive tradition of studies on the topic, which, however, have paid little attention to online dictionaries. Accordingly, to contribute to the development of this area of research, which is of relevance at the present cultural moment, this article presents the analysis of the treatment of a representative sample of ethnophaulisms in the "powered by Oxford" Lexico.com.1 Lastly, preliminary conclusions are drawn and future research avenues are presented.

2. Ethnophaulisms in language, dictionaries, and society

As Iamartino (2020: 36) observes, when dealing with the relationship between language, dictionaries, and society, of special interest are all those entries that belong to sensitive or taboo issues in a given culture and historical period: political and social ideas, religious faith, age, sex, gender, and ethnicity. Regarding the last-mentioned, since the development of political correctness in the late 20th century thanks to the civil rights movements (see Pinnavaia 2020), ethnic slurs have turned into a new social taboo (Zgusta 2000; Wachal 2002; Green 2005). They have become increasingly offensive and racial abuse has been evaluated as the most derogatory area of language, considered to be even more severe than profanities (Allan and Burridge 2006: 105).

According to Hughes (2010: 11-12), among "inappropriate linguistic behavior", and especially "in the category of swearing, only ethnic slurs qualify unambiguously" as politically incorrect, while "religious swearing generally does not" and "sexual swearing is divided along gender lines". Since the degree of tolerance towards politically incorrect or taboo language varies across space and time, depending on the ever-changing values and belief systems of societies, the sociocultural dynamics behind "the evolving nature of taboo" are reflected by dictionaries and "revealed in changes to lexicographic conventions" (Allan and Burridge 2006: 105, 108). Consequently, notwithstanding the perennial "dilemma between inclusiveness and 'decency'" (Hughes 2006: ix) or omission, or between inclusiveness and "censorship" (Mackintosh 2006: 54), since the late 20th century, in response to social pressure, "dictionaries makers have been much more regulative in their policy" and started to "clearly explain, label and exemplify offensive senses and uses in the dictionary's metalanguage" (Allan and Burridge 2006: 108).

Considering the increasingly sensitive nature of this lexical field, it comes as no surprise to learn that in the long and productive tradition of studies that have examined the treatment of ethnophaulisms in English monolingual lexicography, academic attention from this critical perspective has intensified exactly since the late 20th century. Scholars have addressed this topic in particular, or as part of a wider phenomenon like offensive or bad language, taboo words, and sensitive terms, with different approaches and foci: they have investigated only one lemma or a group of ethnophaulisms, only one or more dictionaries, of the same or different type and size, designed for the same or different users, concentrating on the same or different aspects of dictionary entries (cf. Murphy 1991, Norri 2000, Pinnavaia 2014). As a result, the literature is extremely rich and heterogeneous. Furthermore, and more relevantly for this article, very few studies have observed general-purpose online dictionaries, at least to an extent and they have highlighted different aspects of the English language of ethnic conflict (cf. Henderson 2003, Nissinen 2015, Zugic and Vukovic-Stamatovic 2021).

Of studies including online dictionaries, Henderson (2003) focuses on the treatment of a group of ethnic slurs used for black and white Americans in five monolingual dictionaries, two of which are online sources, namely Merriam-Webster's online Collegiate Dictionary (MWOCD 2001) and the historical Oxford English Dictionary Online (OEDO 2002). Henderson (2003: 56-57) shows that, although all five dictionaries include a higher number of slurs for black people compared to those for white people, the OEDO records the most slurs but does not present any consistent pattern in labeling them, as opposed to the MWOCD, which tends to describe words applied to black people and words applied to white people as offensive and disparaging, respectively. The OEDO (2015) is also the only non-learner online dictionary, out of a total of 20 reference works of different types and sizes, British and American, examined by Nissinen (2015) in her study on the treatment of 37 potentially offensive nationality words. According to the research, the OEDO proved to be the dictionary which records the highest number of ethnophaulisms (35 out of 37), whose offensiveness is indicated in 69% of instances through the use of labels, definitions, usage notes, or a combination of these sections (Nissinen 2015: 56-57). Of a different nature is the research carried out by Zugic and Vukovic-Stamatovic (2021), which concentrates on the qualitative analysis of the definition of one single lemma, namely the word for Albanian, in a group of 19 online and freely accessible monolingual dictionaries of multiple languages. As concerns English, as the authors explain (2021: 183-185), these mostly include learner's dictionaries and only three general-purpose works comprising the Merriam-Webster.com dictionary site (2020), The Random House Unabridged Dictionary hosted on the Dictionary.com site (2020) and The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (2020) hosted on Thefreedictionary.com site.

Going back to the great academic interest the topic has attracted in more general terms, a prime example of the heterogeneity of the literature is the wide range of labels scholars have used to term the phenomenon under scrutiny since the late 20th century. Such labels include "terms for racial abuse" (Burch-field 1980), "people names" or "ethnonyms" (Rader 1989), "words offensive to groups" (McCluskey 1989), "racial labels" (Murphy 1991, 1997, 1998), "the language of racism" or "racist language" (Hauptfleisch 1993; Krishnamurthy 1996), "derogatory words for nationality and for a racial or cultural group" (Norri 2000), "racial slurs" (Himma 2002), "taboo words" (Wachal 2002), "offensive language" or "offensive items" (Coffey 2010; Schutz 2002), "ethnocentrism" (Benson 2001), "ethnic slurs" or "ethnic epithets" (Croom 2015; Henderson 2003; Pullum 2018), "bad language words" (Pinnavaia 2014), "ethnocentricity" (Moon 2014), "insulting nationality words" (Nissinen 2015), and "ethnicity terms" (Zugic and Vukovic-Stamatovic 2021), among others. Nevertheless, as Filmer (2011: 21-25) argues, "whichever term we use to denote ethnophaulisms", they "are the linguistic manifestation of one culture's attitudes to the other", and, as such, they evidence the language of intercultural or ethnic conflict, which is the focus of this research.

"The language of ethnic conflict", as seminally defined by Allen (1983), is a long-standing universal phenomenon. As Palmore (1962: 442) has remarked, "it seems to be universal for racial and ethnic groups to coin derogatory terms and sayings to refer to other ethnic groups". In the words of Allan and Burridge (2006: 83), "all human groups, it seems, have available in their language a derogatory term for at least one other group with which they have contact". In sum, as Filmer (2011: 18) observes, a tendency to intolerance towards ethnic diversity has manifested itself linguistically since humans began traveling and encountering peoples from other cultures and religions. This offers a reasonable explanation why the first offensive ethnic epithets appeared in the English language in the Middle Ages (Hughes 2006: 147).

Thus, thousands of "ethnophaulisms" exist across languages. This term was first introduced by American psychologist Abraham Aaron Roback (1944) in his Dictionary of International Slurs (Ethnophaulisms). It refers to "a contemptuous expression for (a member of) a people or ethnic group; an expression containing a disparaging allusion to another people or ethnic group", as defined by the "powered by Oxford" Lexico.com.

According to Hughes (2006: 146), in the English-speaking world, this lexical field shows stages of growth and decline, stages of comparative stasis and marked expansion, linked to "periods of migration, religious conflict, war, territorial expansion, political and business rivalry, immigration, and colonialism". However, since Anglophone cultures have had contact with other ethnicities for centuries, and almost always from a dominant position, English has developed an extremely vast array of ethnophaulisms, especially if compared to other languages such as Italian (Filmer 2011, 2012).

Ethnophaulisms give voice to intercultural or ethnic conflict, they represent verbal expressions of ethnic stereotypes. More specifically, as Reid and Anderson explain (2010: 100), ethnophaulisms are usually "derisive ethnic slurs" which focus on highly distinctive yet concrete aspects of group practices or characteristics (food preference or habits, physical traits, personal and group names). These references allow high-status groups to maintain hierarchies by treating low-status groups as a whole, and the lower the perceived status of a group, the higher the number of and the more negative the nature of ethnophaulisms for that group.

Today, even if we live in a politically correct cultural climate, which "prescribes and proscribes public language for ethnicity, race, gender, sexual preference, appearance, religion, (dis)ability" (Allan and Burridge 2006: 105), we read or hear about hate speech and hate words almost every day (Faloppa 2020). Ethnophaulisms often hit the headlines as the media continue to report these instances of hate speech in the many news concerning verbal and physical attacks against individuals or groups of people of different ethnicities or nationalities. Ethnophaulisms are indeed a prime example of linguistic racism. According to Hughes (2006: 146), they are manifest forms of racial intolerance, "the most obvious linguistic manifestation of xenophobia and prejudice against out-groups [...] based on malicious, ironic, or humorous distortion of the target group's identity or 'otherness'". In Van Dijk's words (2004: 427), they are a form of "racist discourse", one of the major discriminatory practices reproducing racism "as a system of social domination and inequality", and "racist prejudices and ideologies" which "in turn are the basis of discriminatory practices (including discourse)".

3. Methodology

As concerns the working methodology used in this pilot study, two aspects deserve special attention to describe the way lexical items have been identified and analyzed as representative of the English language of ethnic conflict online.

First, as to the selection of ethnophaulisms, given the focus on online lexicography and on the perspective of the Internet general user, the lexemes examined in this pilot study were derived from Wikipedia, because it is the world's largest online encyclopedia and one of the top ten most visited websites in the world (Semrush 2023). More specifically, the terms were collected from the "List of ethnic slurs" (Wikipedia 2023b), which is the first site that appears in Google search results when a general user of the Internet googles 'ethnic slur'. As stated at the beginning of this Wikipedia entry (2023b), "an ethnic slur is a term designed to insult others on the basis of race, ethnicity, or nationality". At the time of this research (August 2022) the Wikipedia list included a total of 430 ethnic slurs, but the number of the terms examined is 285. Further selection has been made according to language-specific criteria and 145 terms were excluded because they belong to languages other than English, including, for example, Italian, Spanish, Arabic, Chinese, Indonesian, Romanian, Japanese, and Russian.

The second important aspect of the methodology used in this study regards the analysis of the entries. Only the lexicographic data which proved to be relevant to the research were scrutinized and they include (a) usage labels, (b) definitions, (c) usage notes, and (d) word origin. Although these data items will be described in-depth in the analysis presented in section 4, some features of the dictionary's entries are worth briefly mentioning here. In the online edition of the Oxford Dictionary of English hosted on "powered by Oxford" Lexico.com, usage labels are shown in italics and placed after grammatical information. Definitions are presented as a list of senses and subsenses, each displayed on a new line, usually numbered if the lemma is polysemous; as concerns polysemy, this study has examined only the ethnicity-related sense of each term. Usage notes and word origins are generally isolated and placed after the definitions. Other sections of the dictionary entries like audio pronunciation and phonetic transcription, grammatical information (word class, plural forms, and spelling variants), usage examples illustrating the usage of the lemma for each sense, and phrases have been excluded from the analysis because they did not contain pertinent data or because they were not included in the dictionary entries (see also section 5 for a brief discussion). Regarding examples, they are taken from the Oxford English Corpus (cf. Atkins and Rundell 2008).

As regards usage labels, special attention is paid to what Jackson (2013: 113) calls "effect labels", which "relate to the effect that a word or sense is intended by the speaker or writer to produce in the hearer or reader". According to Jackson (2013: 113), they are "derogatory" and "offensive", where the difference between the two typically reflects the effect intended and/or perceived by the people involved. Indeed, as Jackson clarifies (2013: 113), while derogatory means "intending to be disrespectful", offensive "may have intent on the part of the speaker or may be unconscious", but it "could be taken by a hearer as offensive, either racially or in some other way". Similarly, the dictionary itself defines derogatory as "showing a critical and disrespectful attitude" and offensive as "causing someone to feel resentful, upset, or annoyed".

In the analysis, the 285 ethnophaulisms selected have been further classified according to three major criteria: (1) inclusion, (2) semantic relevance (ethnicity-related lemmas or senses of lemmas) and (3) offensiveness. In particular, semantic relevance and offensiveness have been assessed on the basis of the lexicographic data contained in effect labels, definitions, usage notes, and word origin, to evaluate whether and how the dictionary signals, and thus warns the user against, the racist power of ethnophaulisms.

4. The language of ethnic conflict in "powered by Oxford" Lexico.com

Based on the criteria mentioned in the previous section, three main groups of terms have been identified in the analysis of the English language of ethnic conflict in the dictionary. These groups include terms which are (1) included or excluded, (2) semantically relevant or irrelevant and (3) offensive, i.e., ethno-phaulisms, or not offensive.

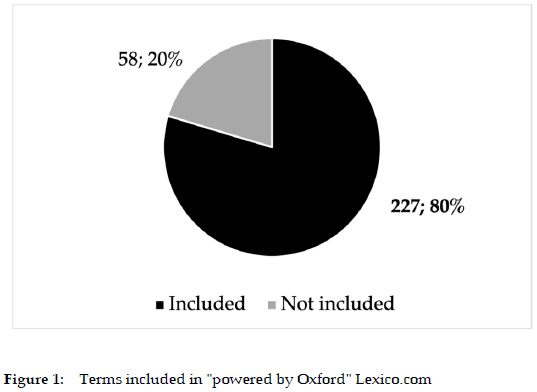

As concerns the first category, namely inclusion, as Figure 1 shows, the dictionary records 227 terms, which represent 80% of the 285 terms selected from wikipedia's list of ethnic slurs.

Figure 1 shows that only 20% of wikipedia's ethnic slurs (58 terms out of 285) are not recorded in the dictionary. These include, for example, armo, "a racial epithet" for "a white person of Armenian descent" (Dalton 2007: 139), eight ball, a name for "a dark-skinned black person" (Dalzell 2018: 261), Leb, Lebo or Lebbo, used derogatorily in Australian English to refer to "a Lebanese person, or any person from an Arabic background" (Dalzell and Victor 2013: 1375), and nig nog, used in British English to denote "any non-white person" (Dalzell and Victor 2013: 1580). As to their exclusion, it is possible to speculate that the dictionary does not record these ethnic slurs because they are no longer in use or because they are expressions confined within single varieties of English.

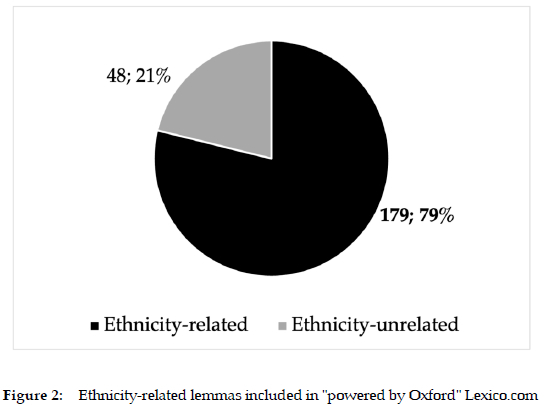

Regarding the second aspect, which is semantic relevance, as shown in Figure 2, only 48 lemmas, that is 21% of the terms included in the dictionary (227), do not present any pertinent ethnicity-related senses.

Semantically irrelevant or ethnicity-unrelated lemmas are mostly common nouns, some of which are polysemic, but the entries for them do not present any senses associated with nationality or ethnicity. Examples include the following lemmas which, according to wikipedia's list of ethnic slurs (wikipedia 2023b) target the ethnicity mentioned, although sometimes only in a variety of English: ape (US black people), apple (NAm native Americans), banana (NAm Asian people), coconut (US, UK, NZ Hispanics, or Latinos), pancake (Asian people), snow-flake (US white people), and teapot (black people). Other interesting examples in this group are goombah and shylock. In the dictionary, goombah is not given as a US derogatory name for an Italian-American, as Dalzell (2018: 350) defines it, but only as an informal North American noun denoting "an associate or accomplice, especially a senior member of a criminal gang". Similarly, shylock, as an allusion to the Jewish moneylender in Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice, is only an offensive epithet for "a moneylender who charges extremely high rates of interest", but it is not said to be an anti-Semitic slur, as it is often considered and perceived today (Rothman 2014).

As shown in Figure 2, the most important group of terms identified in the analysis includes 179 ethnicity-related lemmas, which represents 79% of the lemmas included in the dictionary. In particular, based on the usage information the dictionary offers about the discriminatory potential of these words or of one of their senses, 146 ethnicity-related entries are treated as ethnophaulisms, as Figure 3 illustrates.

Ethnophaulisms represent 82% of the ethnicity-related lemmas. Thus, only 33 lemmas, the remaining ethnicity-related entries (18%), are not treated as ethnic slurs. Since potential offensiveness is not signaled, there is no indication in the dictionary of them belonging to the language of ethnic conflict. Instances of non-ethnophaulisms encompass terms like ang moh, used in Singapore English to refer to "A white person", Indon, an informal Australian noun for "A person from Indonesia", Mr. Charlie, which in African American usage means "A white man", and also rosbif, an informal and humorous epithet originally used among French speakers to denote "An English person". As the examples show, although the senses of these entries are associated with ethnicity or nationality, since the dictionary does not provide any usage data about their potentially derogatory or offensive nature, users may not interpret them as ethnophaulisms.

To conclude this part of the analysis, before discussing the treatment of ethnophaulisms in more detail, it is worth highlighting that, overall, out of the total number of wikipedia's ethnic slurs explored (285), the majority are not only included (80%) and with the relevant sense (63%), but more than half of them (51%) are treated as ethnophaulisms.

4.1 The treatment of ethnophaulisms

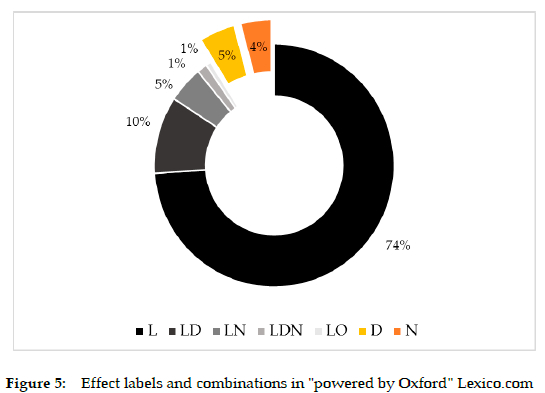

Concerning the treatment of ethnophaulisms in the dictionary, as Figures 4 and 5 illustrate, effect labels (L) are the major dictionary markers indicating offensive-ness, either alone (108, 74%) or in combination with other sections of the entries (25, 17%), thus accounting for a total of 91% (L and L+). The combinations include label and definition (LD, 10%), label and usage note (LN, 5%), label, definition, and usage note (LDN, 1%), and label and word origin (LO, 1%). Moreover, to a limited extent, relevant usage information about offensiveness can also be found in definitions alone (D, 5%) and usage notes alone (N, 4%).

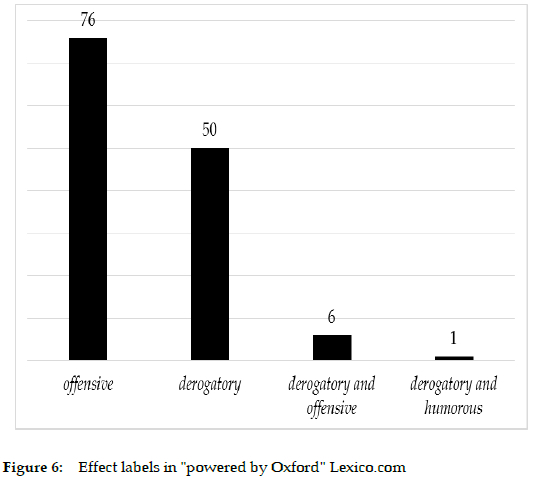

Effect labels are thus the first and most commonly used lexicographic information dictionary users find regarding offensiveness. Like all usage labels, they are highlighted in italics and placed at the beginning of the entry or of the sense they describe, depending on whether the lemma is monosemous or polysemous. Effect labels are assigned to 133 ethnophaulisms in the dictionary, and, as Figure 6 shows, they include 76 terms labeled offensive (57%), 50 terms labeled derogatory (38%), six presenting both labels (4%), and one labeled derogatory and humorous (1%). As regards the last-mentioned, the lemma is gringo, a noun characterized as derogatory and humorous meaning "(in Spanish-speaking countries and contexts, chiefly in the Americas) a person, especially an American, who is not Hispanic or Latino".

Going back to the two major effect labels, they can both occur with other usage labels, including temporal, stylistic, and geographical ones. Nevertheless, while offensive is not further specified, the derogatory effect of a term is also a matter of degree and frequency: on closer inspection, indeed, this label can be further qualified as mainly derogatory (10 occurrences) or often derogatory (8 occurrences), which are minor instances out of the total of 50 occurrences.

To cite some examples, the lemmas labeled offensive include Abo and boong, both meaning "an aboriginal person" in Australian English, beaner for "a Mexican or person of Mexican descent" in North American English, bogtrotter for "an Irish person", and spook, which presents an offensive sense labeled US and dated and meaning "a black person".

The lemmas labeled derogatory comprise Argie, an informal British expression for "a person from Argentina; an Argentinian", goy, which is used in informal language as "a Jewish name for a non-Jewish person", and kraut, an informal epithet for "a German". Moreover, mainly derogatory are, for example, Limey to name a British person and also Jock, Paddy, and Taffy meaning "a Scotsman", "an Irishman", and "a Welshman" respectively, all representing informal nouns "often used as a form of address". Labeled as often derogatory are, for instance, seppo, "an American person", and pocho, used in informal style for "a US citizen of Mexican origin; a culturally Americanized Mexican".

Another interesting subgroup of lemmas accompanied by effect labels are those defined as being both derogatory and offensive, including entries like coon-ass, dothead, Jew boy, Rastus, and Uncle Tomahawk. However, it must be clarified that in one entry only, i.e., the gendered Jew bow, meaning "a (typically young) Jewish male", is the offensive label not further associated with a geographical variety, which, in almost all cases, is US English. For example, dothead is said to be a slang, derogatory, offensive US term for "a person of South Asian origin or descent", while coonass is described as a dialect, derogatory, offensive US term for "a Cajun; a native inhabitant of Louisiana".

As shown in Figures 4 and 5, the second section warning the user against the discriminatory nature of these words in the dictionary entries is the definition, either alone (7 instances, 5%) or with other sections, namely usage labels (15 instances, 10%) or usage labels and usage notes (two, 1%). As to the marking of offensiveness in definitions only, the relevant information is always provided in brackets and corresponds to single labels, as in frog-eater, "especially (derogatory) a French person or a person of French descent", or it corresponds to longer usage descriptions as in slant-eyed, "(often used as an insult towards people of Japanese or Chinese origin)". When definitions reinforce the information also given in other sections, we can observe the following recurrent pattern in the phrasing of the descriptions: A/an + effect adjective + term for + a/an + ethnic adjective + person. The most frequently used effect adjective is 'contemptuous' in "a contemptuous term for" representing 59% of instances (ten occurrences out of 17), which always co-occurs with the label offensive, as in the entries for Chink (Chinese person), coon and nigger (black or dark-skinned person), Jap and Nip (Japanese person), kike and sheeny (Jewish person). Other effect adjectives in this phrasing pattern include derogatory and offensive, as in "A derogatory term for" and "An offensive term for".

The third section of the entry examined is the usage note, which, in the dictionary, is placed in its own box below the definition. This strategy includes instances in which the potential offensiveness is indicated in usage notes only (4%) or in usage notes combined with other sections, that is to say, combined with usage labels (5%) or with usage labels and definitions (1%). The usage notes in the dictionary vary in the quantity and quality of information offered: some focus on current usage only, while other notes, most of them, are more elaborate and also provide information relating to the origin of words.

For example, the note under gypsy states that "the word Gypsy is now sometimes considered derogatory or offensive and has been replaced in many official contexts by Romani or Roma, but it remains the most widely used term for members of this community among English speakers". More firmly, the note for Indian, examined in the sense "a member of any of the indigenous peoples of North, Central, and South America, especially those of North America" and not in the sense "a native or inhabitant of India, or a person of Indian descent", states that this term and Red Indian "are today regarded as old-fashioned and inappropriate, recalling, as they do, the stereotypical portraits of the Wild West". In addition, the note claims that, although American Indian is well established, if possible, users should refer to specific peoples, and finally it mentions European colonization with Columbus's journeys to the Americas as the origin of this sense of Indian.

In other entries, usage notes combine with effect labels or with labels and definitions to warn users against offensiveness. Like the ones mentioned earlier, these usage notes also vary in length and in the quantity and quality of information. An example is the entry for nigger, which is labeled offensive, defined as "a contemptuous term for a black or dark-skinned person". According to the usage note (original emphasis):

The word nigger has been used as a strongly negative term of contempt for a black person since at least the 18th century. Today it remains one of the most racially offensive words in the language. Also referred to as 'the n-word,' nigger is sometimes used by black people in reference to other black people in a neutral manner (in somewhat the same way that queer has been adopted by some gay and lesbian people as a term of self-reference, acceptable only when used by those within the community).

Lastly, as Figure 5 shows, the analysis has shown that the dictionary once also signaled offensiveness in the word origin box. More specifically, the lemma mounseer, labeled slang, derogatory, rare, and archaic, is defined as "a Frenchman". The etymological section reads as follows: "Mid 18th century; earliest use found in The Gentleman's Magazine. Representing an archaic pronunciation of French monsieur which survived as a colloquialism down to the 19th century, and occasionally appears in colloquial speech or in pejorative contexts with reference to English prejudice against foreigners".

5. Conclusions

As Gouws (2018: 215) states, "the era of Internet lexicography confronts lexicographers with challenges and opportunities to enhance the quality of the lexicographic practice and to produce dictionaries that help in satisfying the lexicographic needs" of their users. This is particularly true in users' wider sociocul-tural contexts, where ethnophaulisms prove to be one of those challenges and opportunities, especially for the "powered by Oxford" dictionary content, whose market-leading position cannot but influence the way Internet users deal with sensitive and taboo language issues in this digital age.

To summarize the main points and findings of this research, it seems reasonable to conclude that, despite the limitations of a pilot case study, the analysis shows that the online edition of the Oxford Dictionary of English hosted on the "powered by Oxford" Lexico.com quite clearly reflects the taboo nature of ethno-phaulisms and quite consistently tends to warn the Internet user against the potentially racist and xenophobic power of these words. Indeed, the large majority of Wikipedia's ethnic slurs, that is 80%, is included in the dictionary (227/285), of which 79% are ethnicity-related entries (179/227), of which 82% are treated as ethnophaulisms (146/179).

Relevant and clear usage data tend to appear immediately before the definitions: labels indicate the either offensive or derogatory effect of the relevant lemmas or of one of their senses in 91% of entries, 57% of which define their use specifically as offensive, which means "causing someone to feel resentful, upset, or annoyed", according to the dictionary's own definition. Other important sections of the dictionary entries play a role too, although a minor one, either alone or combined with other sections. Definitions (16%) and usage notes (10%) contribute to what seems to be a quite prescriptive approach of the dictionary to ethnophaulisms and, thus, to racial abuse, which might be interpreted as symptomatic of greater public awareness and sensitivity to possibly offensive racial references, while stressing the taboo nature of ethnophaulisms.

As Cloete suggests (2014: 482), the role of a dictionary, especially a generalpurpose monolingual online dictionary, "is to reflect the language and thus the culture in which it exists, even if that culture is racist, sexist or in other ways politically incorrect". Cloete (2014: 848) notes further that "exclusion based on offensiveness is not acceptable", because it "might lead to ignorance and misuse". Moreover, as Cloete (2014: 484) claims, "to omit the racist words from a dictionary does not solve anything. Racist attitudes will not simultaneously be wiped out. By omitting these terms, the lexicographer loses the opportunity to warn the user against their hurtful nature". Based on preliminary findings, the online edition of the Oxford Dictionary of English hosted on the "powered by Oxford" Lexico.com website has not lost this opportunity.

However, to achieve the objective of the wider ongoing research project on the treatment of ethnophaulisms in "powered by Oxford" dictionary content, of which this pilot study is part, further research will be carried out on other "powered by Oxford" platforms, such as Google, Yahoo, and Bing search engines, and Microsoft and Apple preinstalled dictionaries, to compare findings across platforms in terms of dictionary content and user experience. In particular, given the clear and increasing tendency among Internet users to 'google' their language issues in this digital age (Jackson 2017: 540), special attention will have to be paid to the analysis of ethnophaulisms in the "powered by Oxford" Google's English dictionary (Ferrett and Dollinger 2021, Oxford Languages 2023). This study will be also further developed in order to cover the analysis of usage examples. In this regard, although they were excluded from this initial stage of research, it is relevant to mention that some illustrative examples are provided in 58 entries only, of which 30 are treated as ethnophaulisms, meaning that the dictionary does not exemplify the use of ethnic slurs in 80% of instances. This aspect seems to suggest an interesting tendency that deserves special attention, because examples are a fundamental and sometimes controversial lexicographic component of dictionary entries, as far as socioculturally sensitive issues are concerned (see Pettini 2021).

Endnotes

1 All lexicographic data cited and discussed in this pilot study are from the online edition of the Oxford Dictionary of English hosted on "powered by Oxford" Lexico.com (as of August 26, 2022), which is also referred to as simply "the dictionary" where applicable.

References

Allan, K. and K. Burridge. 2006. Forbidden Words: Taboo and the Censoring of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Allen, I.L. 1983. The Language of Ethnic Conflict: Social Organization and Lexical Culture. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Atkins, B.T.S. and M. Rundell. 2008. The Oxford Guide to Practical Lexicography. Oxford: University Press. [ Links ]

Béjoint, H. 2016. Dictionaries for General Users: History and Development; Current Issues. Durkin, P. (Ed.). 2016. The Oxford Handbook of Lexicography: 7-24. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Benson, P. 2001. Ethnocentrism and the English Dictionary. London/New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Burchfield, R. 1980. Dictionaries and Ethnic Sensibilities. Michaels, L. and C. Ricks (Eds.). 1980. The State of the Language: 15-23. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cloete, A.E. 2014. The Treatment of Sensitive Items in Dictionaries. Gouws, R.H., U. Heid, W. Schweickard and H.E. Wiegand (Eds.). 2014. Dictionaries. An International Encyclopedia of Lexicography Supplementary Volume: Recent Developments with Focus on Electronic and Computational Lexicography: 482-486. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter.

Coffey, S. 2010. 'Offensive' Items, and Less Offensive Alternatives. Dykstra, A. and T. Schoonheim (Eds.). 2010. Proceedings of the XIV EURALEX International Congress, Leeuwarden, 6-10 July 2010: 1270-1281. Leeuwarden/Ljouwert: Fryske Akademy - Afük

Croom, A. 2015. The Semantics of Slurs: A Refutation of Coreferentialism. Ampersand 2: 30-38. [ Links ]

Dalton, C.H. 2007. A Practical Guide to Racism. Sheridan, WI: Gotham Books. [ Links ]

Dalzell, T. (Ed.). 2018. The Routledge Dictionary of Modern American Slang and Unconventional English. Second edition. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Dalzell, T. and T. Victor (Eds.). 2013. The New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English.Second edition. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Dictionary.com. 2023. 'About'. https://www.dictionary.com/e/about (July 4, 2023)

Faloppa, F. 2020. L'hate speech, questo sconosciuto. Speciale "Hate Speech". Lingua Italiana Treccani, October 05, 2020. https://www.treccani.it/magazine/lingua_italiana/speciali/Hate_speech/01_Faloppa.html (April 22, 2023)

Ferrett, E. and S. Dollinger. 2021. Is Digital Always Better? Comparing Two English Print Dictionaries with Their Current Digital Counterparts. International Journal of Lexicography 34(1): 66-91. [ Links ]

Filmer, D. 2011. Translating Racial Slurs: A Comparative Analysis of Gran Torino Assessing Transfer of Offensive Language between English and Italian. Unpublished MA thesis. Durham, UK: Durham University. [ Links ]

Filmer, D. 2012. The 'gook' goes 'gay': Cultural Interference in Translating Offensive Language. inTRAlinea 14. http://www.intralinea.org/archive/article/1829 (April 22, 2023) [ Links ]

Gagliardone, I., D. Gal, T. Alves and G. Martinez. 2015. Countering Online Hate Speech. Paris: UNESCO Publications. [ Links ]

Gouws, R. 2018. Internet Lexicography in the 21st Century. Engelberg, S., H. Kämper and P. Stor-johann (Eds.). 2018. Wortschatz: Theorie, Empirie, Dokumentation: 215-236. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Green, J. 2005. Wash Your Mouth Out. Critical Quarterly 46(1): 107-111. [ Links ]

Hauptfleisch, D.C. 1993. Racist Language in Society and in Dictionaries: A Pragmatic Perspective. Lexikos 3: 83-139. [ Links ]

Henderson, A. 2003. What's in a Slur? American Speech 78(1): 52-74. [ Links ]

Himma, K.E. 2002. On the Definition of Unconscionable Racial and Sexual Slurs. Journal of Social Philosophy 33(3): 512-522. [ Links ]

Hughes, G. 2006. An Encyclopedia of Swearing: The Social History of Oaths, Profanity, Foul Language, and Ethnic Slurs in the English-Speaking World. Armonk M.E. Sharpe.

Hughes, G. 2010. Political Correctness: A History of Semantics and Culture. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell. [ Links ]

Iamartino, G. 2020. Lexicography as a Mirror of Society: Women in John Kersey's Dictionaries of the English Language. Textus: English Studies in Italy 33(1): 35-67. [ Links ]

Jackson, H. 2013. Lexicography: An Introduction. London/New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jackson, H. 2017. English Lexicography in the Internet Era. Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. (Ed.). 2017. The Routledge Handbook of Lexicography: 540-553. London: Routledge.

Krishnamurthy, R. 1996. Ethnic, Racial and Tribal: The Language of Racism? Caldas-Coulthard, C. and M. Coulthard (Eds.). 1996. Texts and Practices: Readings in Critical Discourse Analysis: 129-149. London: Routledge.

Lew, R. and G.-M. de Schryver. 2014. Dictionary Users in the Digital Revolution. International Journal of Lexicography 27(4): 341-359. [ Links ]

Lorentzen, H. and L. Theilgaard. 2012. Online Dictionaries - How Do Users Find Them and What Do They Do Once They Have? Vatvedt Fjeld, R. and J.M. Torjusen (Eds.). 2012. Proceedings of the XV EURALEX International Congress, 7-11 August, 2012, Oslo: 654-660. Oslo: Department of Linguistics and Scandinavian Studies, University of Oslo.

Mackintosh, K. 2006. Biased Books by Harmless Drudges: How Dictionaries are Influenced by Social Values. Bowker, L. (Ed.). 2006. Lexicography, Terminology, and Translation: Text-Based Studies in Honour of Ingrid Meyer: 45-63. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

McCluskey, J. 1989. Dictionaries and Labeling of Words Offensive to Groups, with Particular Attention to the Second Edition of the OED. Dictionaries: Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America 11: 111-123. [ Links ]

Moon, R. 2014. Meanings, Ideologies, and Learners' Dictionaries. Abel, A., C. Vettori and N. Ralli (Eds.). 2014. Proceedings of the XVI EURALEX International Congress: The User in Focus, EURALEX 2014, Bolzano/Bozen, Italy, July 15-19, 2014: 85-105. Bolzano/Bozen: EURAC Research.

Müller-Spitzer, C. and A. Koplenig. 2014. Online Dictionaries: Expectations and Demands. Müller-Spitzer, C. (Ed.). 2014. Using Online Dictionaries. Lexicographica Series Maior 145: 143-188. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter.

Murphy, M.L. 1991. Defining Racial Labels: Problems and Promise in American Dictionaries. Dictionaries: Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America 13(1): 43-64. [ Links ]

Murphy, M.L. 1997. Afrikaans, American and British Models for South African English Lexicography: Racial Label Usage. Lexikos 7: 153-164. [ Links ]

Murphy, M.L. 1998. Defining People: Race and Ethnicity in South African English Dictionaries. International Journal of Lexicography 11(1): 1-33. [ Links ]

Nissinen, S. 2015. Insulting Nationality Words in Some British and American Dictionaries and in the BNC. Unpublished MA Thesis. Tampere, FI: University of Tampere. [ Links ]

Norri, J. 2000. Labelling of Derogatory Words in Some British and American Dictionaries. International Journal of Lexicography 13(2): 71-106. [ Links ]

Oxford Languages. 2023. Oxford Languages and Google. https://languages.oup.com/google-dictionary-en/ (April 22, 2023)

Palmore, E.B. 1962. Ethnophaulisms and Ethnocentrism. American Journal of Sociology 67(4): 442-445. [ Links ]

Pettini, S. 2021. "One is a Woman, So That's Encouraging Too": The Representation of Social Gender in "Powered by Oxford" Online Lexicography. Lingue e Linguaggi 44: 275-295. [ Links ]

Pinnavaia, L. 2014. Defining and Proscribing Bad Language Words in English Learner's Dictionaries. Iannaccaro, G. and G. Iamartino (Eds.). 2014. Enforcing and Eluding Censorship: British and Anglo-Italian Perspectives: 217-230. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Pinnavaia, L. 2020. Tracing Political Correctness in Bilingual English-Italian Dictionaries. Textus: English Studies in Italy 33(1): 87-106. [ Links ]

Pullum, G.K. 2018. Slurs and Obscenities: Lexicography, Semantics, and Philosophy. Sosa, D. (Ed.). 2018. Bad Words: Philosophical Perspectives on Slurs: 168-192. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rader, J. 1989. People and Language Names in Anglo-American Dictionaries. Dictionaries: Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America 11: 125-138. [ Links ]

Reid, S.A. and G.L. Anderson. 2010. Language, Social Identity, and Stereotyping. Giles, H., S.A. Reid and J. Harwood (Eds.). 2010. The Dynamics of Intergroup Communication: 91-104. New York: Peter Lang.

Roback, A.A. 1944. A Dictionary of International Slurs (Ethnophaulisms). Cambridge, MA: Sci-Art Publishers. [ Links ]

Rothman, L. 2014. When Did 'Shylock' Become a Slur? Time, September 17. https://time.com/3394403/shylock-biden/ (April 22, 2023)

Schutz, R. 2002. Indirect Offensive Language in Dictionaries. Braasch, A. and C. Povlsen (Eds.). 2002. Proceedings of the Tenth EURALEX International Congress, EURALEX 2002, Copenhagen, Denmark, August 13-17, 2002: 637-641. Copenhagen: Center for Sprogteknologi, Copenhagen University.

Semrush. 2023. Top Websites: Most visited Websites by Traffic in the World for All Categories, March 2023. https://www.semrush.com/website/top/ (April 22, 2023)

Statcounter. 2023. Search Engine Market Share Worldwide: March 2023. https://gs.statcounter.com/search-engine-market-share (April 22, 2023)

Van Dijk, T.A. 2004. Racism, Discourse and Textbooks: The Coverage of Immigration in Spanish Textbooks. Paper for the Symposium on Human Rights in Textbooks, organized by the History Foundation, Istanbul. http://www.discursos.org/unpublished%20articles/Racism,%20discourse,%20textbooks.htm (April 22, 2023)

Wachal, R.S. 2002. Taboo or Not Taboo: That is the Question. American Speech 77(2): 195-206. [ Links ]

Wikipedia. 2023a. Lexico. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lexico (April 22, 2023)

Wikipedia. 2023b. List of Ethnic Slurs. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ethnic_slurs (April 22, 2023)

Zgusta, L. 2000. Some Developments in Lexicography, Past and Present. Mogensen, J.E., V.H. Pedersen and A. Zettersten (Eds.). 2000. Symposium on Lexicography IX: Proceedings of the Ninth International Symposium on Lexicography, April 23-25, 1998 at the University of Copenhagen. Lexicographica. Series Maior 103: 11-26. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

Zugic, D. and M. Vukovic-Stamatovic. 2021. Problems in Defining Ethnicity Terms in Dictionaries. Lexikos 31: 177-194. [ Links ]