Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Industrial Engineering

On-line version ISSN 2224-7890

S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. vol.36 n.2 Pretoria Aug. 2025

https://doi.org/10.7166/36-2-3226

GENERAL ARTICLES

A Practical Framework for Integrating Advances in Ergonomics to Improve Productivity in South African Small and Medium Enterprises

T. A. Mukalay*; J. Swanepoel; T. Nenzhelele

Department of Industrial Engineering, Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This study provides a practical framework for integrating advances in ergonomics into South African small and medium enterprises to enhance productivity. Informed by a comprehensive literature review and insights from the 2025 Applied Ergonomics Conference, the proposed three-phase framework comprises an ergonomics intervention trigger checklist and related productivity metrics; an integration matrix aligned with ISO 45001:2018 and ISO TR 12295:2014; and strategies to overcome adoption barriers. The framework incorporates participatory design, simplified assessment tools, and interventions such as wearable technologies. By addressing a gap in the research, this study offers a scalable, cost-effective framework that is tailored to the resource-constrained small and medium enterprises' environment.

OPSOMMING

Hierdie studie bied 'n praktiese raamwerk vir die integrasie van vooruitgang in ergonomie in Suid-Afrikaanse klein en mediumgrootte ondernemings om produktiwiteit te verbeter. Gebaseer op 'n omvattende literatuuroorsig en insigte van die 2025 Toegepaste Ergonomie-konferensie, bestaan die voorgestelde driefase-raamwerk uit 'n ergonomiese intervensie-sneller-kontrolelys en verwante produktiwiteitsmaatstawwe; 'n integrasiematriks wat in lyn is met ISO 45001:2018 en ISO TR 12295:2014; en strategieë om aanvaardingshindernisse te oorkom. Die raamwerk inkorporeer deelnemende ontwerp, vereenvoudigde assesseringsinstrumente en intervensies soos draagbare tegnologieë. Deur 'n gaping in die navorsing aan te spreek, bied hierdie studie 'n skaalbare, koste-effektiewe raamwerk wat aangepas is vir die hulpbronbeperkte klein en mediumgrootte ondernemings se omgewing.

1. INTRODUCTION

SMEs is pivotal to South Africa's economy, as they provide employment to about 60% of the labour force, and contribute an estimated 34% to the country's gross domestic product (GDP) [1]. Despite their significant role, many South African SMEs grapple with difficulties such as low productivity, high incidences of workplace injury, and a limited capacity to implement systems that prioritise occupational health and safety. A critical yet often underused strategy to address these problems is the application of ergonomics. Ergonomics is defined a discipline that studies the interactions among humans and other elements of a system such as tools and machinery, and applies theoretical principles, data, and methods to design to enhance human well-being and overall system performance [2].

Traditionally, the adoption of ergonomic principles has been more prevalent among large corporations, primarily owing to their access to greater financial and technical resources [3]. In contrast, SMEs often perceive ergonomic interventions as costly and as secondary to their core business operations [4]. This perception contributes to suboptimal working conditions, increased absenteeism, and diminished productivity [5, 6].

However, recent advances in the field of ergonomics have introduced innovative, cost-effective solutions that are scalable and adaptable to the unique contexts of SMEs. These innovations, highlighted at the Applied Ergonomics Conference 2025 [7], include affordable participatory design approaches, simplified ergonomics assessment, and wearable technologies that actively involve employees in creating safer and more efficient work environments [8, 9].

This study aims to develop a pratical framework to integrate recent ergononomics advances into South African SMEs to enhance productivity. This work bridges the gap in current research, as there is no practical framework for ergonomics to advance integration into South African SMEs. The following sections define the study: literature review, method, results and discussion, and conclusion.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. Overview

This section reviews the current literature and applied insights into the role of ergonomics in improving productivity in SMEs, with a focus on South Africa. It begins by exploring the evolution of ergonomics, and highlights recent advances in the field [10, 11]. South African SMEs face unique operational difficulties such as limited access to expertise, safety concerns, and infrastructure constraints, which ergonomic interventions may help to mitigate [12]. The review also examines the impact of ergonomics on productivity, while identifying persistent barriers to adoption in developing economies as well as productivity metrics [13]. By synthesising recent scholarly findings and real-world applications, this section lays the groundwork for understanding how ergonomic strategies may improve productivity in South African SMEs.

2.2. Ergonomics: Historical context and contemporary advances

2.2.1. Historical context

The development of ergonomics as a scientific discipline reflects the evolving relationship between humans and work systems. Its roots lie in the Industrial Revolution. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the introduction of scientific management and of time-and-motion studies aimed to improve labour efficiency and reduce fatigue [14]. These efforts laid the groundwork for ergonomic thinking that was focused on optimising performance through structured task analysis.

A significant leap forwards occurred during the two world wars, when the complexity of military equipment and high error rates in aviation and combat operations underscored the limitations of poorly designed interfaces. Alphonse Chapanis's research into pilot errors revealed that intuitive design, not only operator skill, was critical to performance and safety [15]. His work led to foundational human factors principles being used in system design today.

In 1949, the term "ergonomics" gained formal recognition with the founding of the Ergonomics Research Society in the UK. Over the decades that followed, the field expanded from physical ergonomics to encompass cognitive and organisational aspects such as systems that considered mental workload, job design, and workplace culture [16].

2.2.2. Contemporary advances

Ergonomics has constantly evolved since the mid-20th century, incorporating technological innovations and methodological refinements to enhance workplace safety and efficiency. This section focuses on participatory design approaches, simplified ergonomics assessment tools, and wearable technologies.

a. Participatory design approaches (PDAs): During the 1980s and 1990s, participatory ergonomics gained prominence, emphasising the active management commitment and involvement of workers in designing and implementing ergonomic solutions. This collaborative approach ensures that interventions are practically relevant and lead to improved safety outcomes, worker satisfaction, and overall productivity [17].

b. Simplified ergonomics assessment tools (SEATs): To facilitate widespread ergonomic assessments, tools such as ergonomics assessment have been streamlined. Introduced in the late 1990s and early 2000s, these tools allow to evaluate postural risks and to implement corrective measures in order to ensure improved work conditions with minimal investment of resources [18].

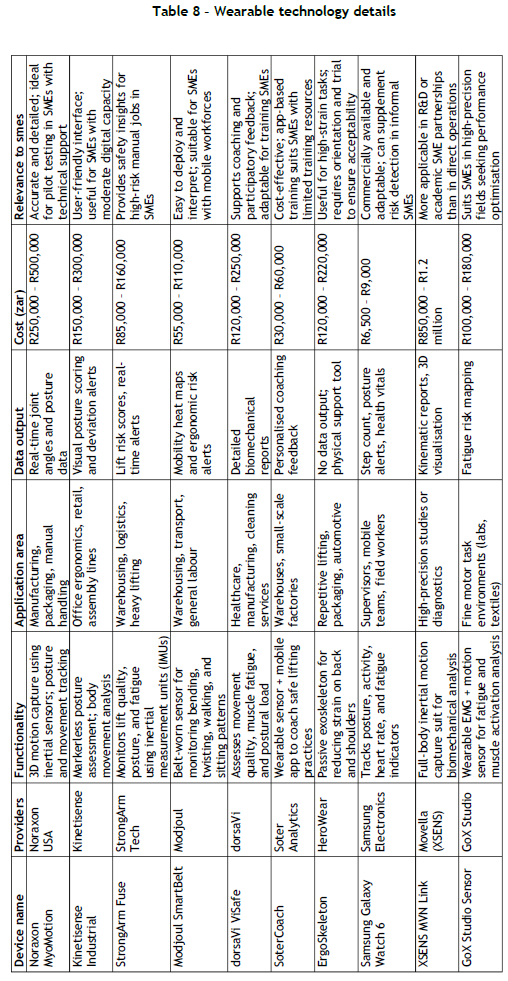

c. Wearable technologies (WTs): The 21st century has seen the advent of WTs in ergonomics. These devices are equipped with sensors that monitor workers' movements and postures in real time, thus providing data to identify risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders. This innovation fosters proactive ergonomics interventions [19]. Table 8 provides a detailed overview of WTs.

2.3. Ergonomics-related difficulties with productivity

The recent literature has highlighted that poor ergonomic practices remain a significant barrier to productivity in South African SMEs. The problems stem from preventable physical stressors, inefficient task design, and organisational limitations that collectively diminish workforce performance. Studies have identified task inefficiency and human error, high absenteeism, equipment mismatch and poor workplace design, low worker engagement and morale, and high employee turnover and training costs as ergonomics-related obstacles to productivity.

2.3.1. Task inefficiency and human error

According to Chindove and Lemmer [20], inefficient task design, caused by a lack of ergonomic integration, results in high error rates, decreased concentration, and longer task execution times. Their review underscores the compounding effect of fatigue and poor posture on operational accuracy and throughput [4].

2.3.2. Absenteeism and presenteeism

A report by Deloitte South Africa [21] estimated that presenteeism costs the economy over R235 billion annually, amounting to roughly 4.2% of GDP, with mental health and ergonomic stressors playing a central role. Absenteeism from preventable ergonomic injuries also affects production schedules and delivery times, particularly in labour-intensive industries [21].

2.3.3. Equipment mismatch and poor workplace design

Findings by Sinno and Ammoun [22] showed that non-adjustable and outdated equipment, which is prevalent in SMEs, impedes productivity by forcing workers into inefficient and injury-prone positions. Their study confirmed that ergonomic mismatch leads to increased microbreaks, slower cycle times, and reduced job satisfaction [22].

2.3.4. Low worker engagement and morale

The Africa Employee Engagement Outlook [23] revealed that only 28% of South African employees feel highly engaged in their roles, with poor working conditions, particularly ergonomic discomfort, highlighted as a key demotivator [23].

2.3.5. High turnover and training costs

Chinyamurindi and Mashavira [24] emphasised that poor ergonomic conditions are a driver of early turnover, especially among younger skilled workers in SMEs. They argued that the recurring costs of recruitment and training as a result of avoidable ergonomic stressors place undue financial strain on SMEs [24].

2.4. Ergonomics assessment tool

Accurately identifying and addressing ergonomics-related productivity problems requires effective diagnostic tools, especially in resource-constrained environments such as South African SMEs. Ergonomics assessment tools offer structured approaches to evaluate the physical and cognitive demands of tasks, workstation configurations, and employee feedback [25-32]. These tools are presented in Table 1.

Drawing from Table 1, it is evident that no single tool is universally applicable. Instead, tools should be selected on the basis of task complexity, workforce characteristics, and available expertise. For instance, SMEs with limited technical capacity may favour checklist-based methods or worker feedback surveys, while more advanced organisations may employ biomechanical models such as 3DSSPP.

2.5. Integration of ergonomie advances into SME operations

This section presents a structured framework for integrating ergonomic practices into the operations of SMEs. Grounded in participatory ergonomics, lean thinking, and continuous improvement principles, and aligned with ISO 45001:2018 and ISO/TR 12295:2014 standards [30, 31], the framework outlines eight sequential steps, which range from securing management commitment to embedding ergonomics into the organisational culture.

2.5.1. Management commitment

The foundation of any ergonomic integration strategy is top-level management commitment. Leadership involvement ensures resource allocation, policy support, and alignment with organisational goals [33]. When leadership visibly supports ergonomic initiatives, employee buy-in increases and interventions are likely to succeed. However, several SME leaders may lack awareness of ergonomics or perceive it as a non-essential cost, which would limit its prioritisation [10].

2.5.2. Ergonomics awareness training

Training programmes enhance organisational knowledge of ergonomic risks and solutions. They empower staff to recognise early warning signs of strain and to participate in mitigation strategies. This results in a proactive workforce, which is able to identify and resolve ergonomic issues autonomously. On the downside, training requires time and financial investment, which are often seen as burdensome for SMEs operating under resource constraints [13].

2.5.3. Workplace assessment

Using ergonomics assessment tool allows for the systematic identification of postural and biomechanical risks [18]. These tools are suitable for SMEs owing to their cost-effectiveness. However, they may not capture dynamic or psychosocial factors that influence ergonomic risk [35].

2.5.4. Employee participation

Active employee involvement fosters ownership and ensures that ergonomic solutions are relevant to actual work conditions. This participatory approach improves the practicality and sustainability of interventions. However, achieving consistent participation can be difficult, especially in SMEs where employees are spread across multiple roles or functions [17].

2.5.5. Identification of risk factors

Identifying ergonomic risk factors such as repetitive motions, awkward postures, and excessive force is essential for developing targeted interventions. Modern techniques, such as WTs, allow for precise identification [36]; however, the granularity of the data may overwhelm SMEs that lack in-house expertise to interpret and act on the findings [37].

2.5.6. Implementation of ergonomic interventions

Once risks are identified, SMEs can introduce interventions such as workstation redesign, tool modifications, or schedule changes. These changes have been shown to reduce injury rates and improve operational efficiency [27]. However, implementation may require capital investment or process restructuring, which can be perceived as disruptive or unaffordable for SMEs [18].

2.5.7. Monitoring and evaluation

Continual monitoring ensures that interventions remain effective and adapt to evolving work conditions. Feedback mechanisms can highlight unintended consequences or new risks [5]. However, SMEs may struggle with data collection and long-term tracking because of limited administrative capacity and their prioritisation of short-term outputs [37].

2.5.8. Continuous improvement

Ergonomics becomes effective when integrated into an organisational culture of continuous improvement. Iterative refinements allow for the gradual evolution of safe and productive work practices [33]. Nonetheless, without formal feedback and learning systems, continuous improvement efforts may stagnate, especially in SMEs without established quality or safety programmes [11].

2.6. Alignment of advances in ergonomics and integration steps

Table 2 provides a structured alignment of recent advances in ergonomics, namely participatory design, SEATs, and WTs and the corresponding integration steps. This alignment reinforces the practical value of each innovation by linking it to specific stages in ergonomic implementation, from initial management commitment to continuous improvement. Table 2 shows that management commitment, employee buy-in, and continuous improvement are critical for participatory design. Training, assessment, and early-stage risk identification are critical to support the use of assessment tools. Last, the effective implementation of WTs should be monitored and evaluated to foster continuous improvement.

2.7. Evaluating impact of ergonomics on SME productivity

Table 3 presents a practical evaluation of the impact of ergonomic interventions on productivity in SMEs. Drawing on 10 real-world case studies, the analysis shows that ergonomic enhancements, ranging from workstation redesigns to participatory risk assessments, consistently lead to measurable gains in efficiency, quality, safety, worker satisfaction, and overall productivity. Each case illustrates how addressing specific ergonomic challenges results in tangible productivity benefits.

2.8. Barriers to adoption in developing economies

The adoption of ergonomie principles in SMEs in developing economies is often constrained by a complex interplay of economic, institutional, and operational factors. This section reviews barriers identified in the South African SME environment.

2.8.1. Limited financial resources

Cost remains the most frequently cited barrier to ergonomic adoption. Many SMEs operate on constricted margins and prioritise immediate survival over long-term investments such as ergonomic improvements. Voon et al. [10] found that, in most SMEs, ergonomic tools, training, and workplace redesigns are perceived as non-essential expenses despite their long-term return on investment. The upfront cost of equipment is often unattainable without external support or subsidies.

2.8.2. Lack of ergonomic awareness

A major non-monetary barrier is the lack of awareness and understanding of ergonomics in SMEs. As noted by Esterhuyzen [13], many SMEs are unfamiliar with the concept of ergonomics or view it as a "luxury" concern for larger organisations. This knowledge gap results in a lack of internal motivation to seek improvements or to recognise the linkage between workplace design and productivity.

2.8.3. Insufficient training and expertise

Even when awareness exists, the absence of skilled personnel to assess and implement ergonomic solutions is a significant obstacle. Hasle and Limborg [35] argued that SMEs rarely employ full-time safety or ergonomics officers, relying instead on general managers or supervisors without formal training.

2.8.4. Organisational cultural perceptions and resistance to change

Organisational cultural attitudes in SMEs may also hinder the adoption of ergonomic practices. Change may be perceived as disruptive or unnecessary, particularly if older work habits have become normalised. Legg et al. [37] emphasised that, in environments where survival is prioritised over efficiency, resistance to innovation can block even low-cost ergonomic interventions.

2.8.5. Inadequate government support

The absence of targeted government policies or financial incentives to promote ergonomics in SMEs is another barrier. While occupational safety laws exist, they often lack ergonomies-specific enforcement or funding mechanisms. Esterhuyzen [13] noted that ergonomic awareness campaigns and compliance support are limited in developing countries such as South Africa, particularly outside urban centres.

2.8.6. Limited access to technology

SMEs in developing economies frequently lack access to technology that supports modern ergonomic interventions. Voon et al. [10] observed that such tools have become critical for advanced ergonomic applications, but remain inaccessible to most SMEs because of cost, inadequate infrastructure, or lack of technical literacy.

2.8.7. Weak regulatory enforcement

Even when regulations exist, enforcement is often inconsistent. SMEs may not face consequences for non-compliance with ergonomic standards or those outlined in the Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) Act 85 of 1993 and in ISO 45001:2018. Legg et al. [37] stressed that weak institutional oversight reduces the perceived importance of ergonomics.

2.8.8. Competing operational priorities

Last, SME owners often focus on survival-oriented tasks such as securing contracts, paying wages, and managing cash flow. As a result, ergonomic improvements are deprioritised. Hasle and Limborg [35] found that day-to-day firefighting overrides long-term planning in SMEs.

2.9. Productivity metrics for ergonomic intervention evaluation

In the context of this study, productivity metrics serve as indicators of changes in work performance, efficiency, and employee well-being that result from ergonomic interventions. Integrating these metrics into the proposed ergonomic framework should enable the systematic monitoring of interventions. Table 4 presents a summarised list of quantitative and qualitative metrics.

Table 4 above presents quantitative and qualitative productivity metrics that have been adapted from the literature and been used in various industries in the South African SME landscape. Moreover, productivity metrics should be aligned with the ergonomics-related productivity problem that needs to be addressed in order to achieve an effective intervention.

2.10.Summary

The literature reveals that ergonomics has evolved from its early roots in industrial efficiency and military safety to a multidisciplinary science that encompasses physical, cognitive, and organisational elements. Contemporary advances such as participatory design, simplified assessment tools, and WTs have expanded the reach and effectiveness of ergonomic practice. These innovations have become increasingly adaptable to resource-constrained environments, making them relevant to South African SMEs.

The integration of ergonomic practices into SME operations has shown positive outcomes in multiple case studies. Whether through workstation redesigns, layout changes, or tool adjustments, ergonomic interventions have led to measurable improvements in productivity. Despite their economic importance, South African SMEs often operate under intense constraints, making long-term investments in workplace optimisation difficult regardless of the benefits of ergonomic interventions.

Significant barriers also hinder the widespread adoption of ergonomics in developing economies. These include limited financial resources, lack of awareness, insufficient training, resistance arising from the existing organisational culture, and weak regulatory frameworks. Even when the ergonomic benefits are clear, SMEs often prioritise short-term survival over long-term improvements. This situation is further complicated by the lack of targeted government support and accessible technology. To overcome these constraints, this study proposes an eight-step ergonomic integration framework that incorporates measurable productivity metrics. This method offers a pragmatic pathway for embedding ergonomics advances - namely, participatory design, simplified assessment tools, and WTs in SMEs operations. The next section describes the proposed framework.

3. METHOD

3.1. Overview

This section presents a literature-based approach to integrating ergonomic innovations into South African SMEs. The framework involves three ergonomics interventions - namely, the WTs to enable real-time monitoring and reduce ergonomic risks; SEATs tailored for ease of use and low-resource settings; and PDAs that engage workers in developing and improving practical context-specific solutions.

3.2. Research approach

This study followed a qualitative conceptual research approach. Building on the literature review, the research developed a structured framework that would enable South African SMEs to adopt ergonomic solutions that are scalable, cost-effective, and locally relevant.

3.3. Material

3.3.1. Ergonomics-related difficulties with productivity

The literature identifies several ergonomics-related problems that directly hinder productivity in SMEs -see section 2.3 above. The presence of one or more of these conditions should serve as a trigger for initiating ergonomic interventions, as they may impair operational performance and workforce sustainability.

3.3.2. Productivity metrics

Productivity metrics should be clearly defined and relevant data collected prior to the intervention in order to establish a baseline to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention - see Section 2.8.

3.3.3. Barriers to ergonomics adoption

The literature indicates that the implementation of ergonomic interventions and advancements in South African SMEs is significantly hindered by several interrelated barriers - see Section 2.7. The proposed framework should systematically address these barriers.

3.3.4. Ergonomics integration process

The literature suggests that an effective integration of ergonomic interventions in SMEs should follow a structure, such as that presented in Section 2.5. These steps should enable both ergonomic innovations and established standards.

3.4. Framework development process

The framework focuses on translating ergonomic innovations into actionable strategies that are suited to resource-constrained environments - see Figure 1. While the integration process and adoption barriers have been included in the proposed framework, the ergonomics-related difficulties with productivity should serve as a map to identify potential areas of concern and to select and/or adapt productivity metrics to evaluate the intervention's effectiveness.

Step 1 A - Management commitment: The foundation of ergonomic integration is strong leadership support. The framework begins with securing management commitment. The financial constraint and competing operational priorities are barriers to be overcome.

Step 1 B - Employee participation: Employees have first-hand knowledge of operational inefficiencies and ergonomic hazards. Their involvement through participatory design workshops and feedback sessions ensures that solutions are both relevant and accepted. The organisational cultural perceptions and resistance to change are barriers to be overcome.

Step 2 - Ergonomics awareness training: Limited knowledge of ergonomics is a major constraint in South African SMEs. This step introduces tailored training sessions to build a shared understanding of ergonomic principles, assessment tools, risk factors, and practical benefits. The lack of ergonomics awareness and insufficient expertise are barriers to be overcome.

Step 3 - Workplace assessment: This step involves evaluating high-risk tasks and environments using assessment tools. SMEs often operate with outdated or poorly designed equipment and spaces, leading to avoidable productivity losses. The limited access to technology and insufficient expertise are barriers to be overcome.

Step 4 - Identification of risk factors: This step consolidates data from assessments and from workers' input to prioritise ergonomic risks that most affect productivity. Risk factors are classified and ranked to guide intervention planning. The limited financial resources and limited access to technology are barriers to be overcome.

Step 5 - Implementation of ergonomic interventions: Selected solutions such as WTs are introduced through a phased rollout. Emphasis is placed on cost-effective and scalable devices that fit SME budgets -see Table 8. The limited financial resources and limited access to technology are barriers to be overcome.

Step 6 - Monitoring and evaluation: This step monitors defined metrics to evaluate the intervention impact - see section 2.8. Continuous data collection ensures that progress is tracked and adjustments are made as needed. Weak regulatory enforcement and conflicting operational priorities are barriers to be overcome.

Step 7 - Continuous improvement: This final step reinforces an organisational culture of ongoing evaluation, worker feedback, and innovation. It encourages SMEs to make ergonomics part of their regular operational reviews, thus sustaining their long-term productivity gains. Inadequate government support and organisational cultural perceptions and resistance to change are barriers to be overcome.

3.5. Summary

This study used a qualitative, literature-driven approach to develop a practical framework for integrating ergonomics into South African SMEs. It focuses on three ergonomics interventions: WTs, SEATs, and PDAs. Ergonomics-related productivity problems such as task inefficiency, absenteeism, and poor workplace design are addressed alongside adoption barriers such as financial constraints, lack of awareness, and organisation cultural resistance to change, and are integrated in the proposed framework. Moreover, this framework incorporates measurable metrics that can be adapted to the business circumstances to evaluate the intervention's effectiveness. The proposed framework provides a practical tool to embed ergonomic practices and to enhance productivity in South African SMEs.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1. Overview

This section presents the developed framework and discusses its relevance to addressing ergonomics-related productivity problems in South African SMEs. In addition, it provides practical steps to overcome the identified ergonomics adoption barriers. This framework comprises an ergonomics intervention trigger checklist and related productivity metrics, integration matrix, and resources to overcome adoption barriers.

4.2. Proposed framework for integration of ergonomic advances

4.2.1. Ergonomic intervention trigger factors

For SMEs, resource constraints often require a reactive approach to workplace improvements. However, understanding and recognising specific ergonomic intervention triggers may help SMEs to act preemptively to prevent losses in productivity before they escalate. Table 5 outlines five triggers that should prompt ergonomic interventions in the South African SME environment. These triggers are aligned with related productivity metrics. It is worth noting that this study identified five triggers based solely on the scope of the study.

4.2.2. Integration matrix

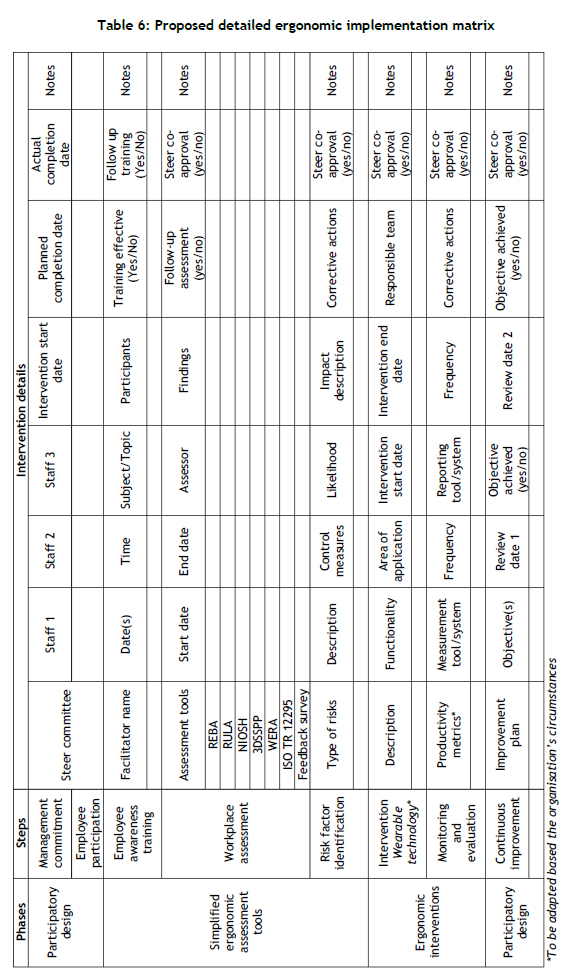

The integration matrix, presented in Table 6, is a practical tool that is designed to guide the systematic integration of ergonomic principles into South African SMEs, with specific alignment with ISO 45001:2018 and ISO TR 12295:2014 standards [30, 31]. It supports organisations in embedding ergonomic practices. As shown in Figure 1, from initial management commitment through to continuous improvement, the matrix ensures that actions are participatory, risk informed, and performance driven.

The integration matrix is organised into three stages: participatory design, simplified ergonomics assessment tools, and ergonomic interventions. Each phase aligns with the steps of ergonomic integration, along with designated fields to capture information such as responsibility, timelines, findings, approvals, and corrective actions.

4.3. Addressing adoption barriers in South African context: Wearable technologies

The implementation of WTs in South African SMEs is constrained by a wide range of barriers. Table 7 presents these barriers along with tailored resolutions that are grounded in the South African context.

4.4. Discussion

The integration of ergonomics into South African SMEs has long been difficult owing to constraints such as limited resources, low awareness, and resistance to change. The proposed three-phase framework comprises the identification of intervention triggers aligned with the related productivity metrics, an integration matrix, and resources to overcome adoption barriers. Each component plays a pivotal role in guiding SMEs from reactive problem-solving to proactive and sustainable ergonomic improvement.

The first phase focuses on identifying specific ergonomic intervention triggers. These triggers, such as high absenteeism, low morale, or high training costs, are warning signs of deeper inefficiencies that could erode productivity further. The trigger factors are aligned to productivity metrics that may be adapted to various industries. Furthermore, the five trigger factors reflect the operational realities of South African SMEs. While this list is not exhaustive, it offers a practical foundation for decision-makers to initiate interventions before productivity losses escalate.

The second phase is operationalised through the integration matrix, which is the core of the framework. The matrix is aligned with ISO 45001:2018 and ISO TR 12295:2014 to ensure that the approach is not only practical but also globally recognised. Each phase in the matrix - participatory design, simplified ergonomics assessment tools, and ergonomics interventions - is designed to ensure that actions are:

• Participatory, involving employees in both identifying issues and co-developing solutions;

• Risk-informed, using validated tools such as REBA, RULA, and WERA;

• Performance-driven, with measurable outcomes and built-in feedback loops.

The matrix acts as a plug-and-play template that guides the organisation through implementation without requiring extensive expertise.

Even with the best design, implementation can stall unless it addresses the barriers to the adoption of ergonomics. The third phase of the framework focuses on contextually relevant resolutions to the common systemic and organisational obstacles in South African SMEs.

Table 7 presents these barriers, from limited financial resources to cultural resistance, alongside tailored solutions and locally available resources, such as Productivity SA grants, SETA training, and AEC 2025 materials.

Moreover, by linking ergonomics to existing SME priorities such as Lean and quality improvement, the framework positions ergonomics not as a compliance burden but as a productivity enabler.

In sum, the proposed framework offers a practical, phased pathway for SMEs to adopt ergonomics in a way that is realistic, participatory, and scalable. It begins with clear intervention triggers and metrics, transitions into structured implementation, and addresses adoption barriers with real-world support mechanisms.

5. CONCLUSION

This study addressed a critical gap in the productivity landscape of South African SMEs by proposing a practical framework for the integration of recent advances in ergonomics. Drawing on a comprehensive literature review, insights from the Applied Ergonomics Conference 2025, and established ISO standards, the study developed a three-phase framework encompassing (i) ergonomic intervention trigger identification and related metrics, (ii) an integration matrix, and (iii) strategies to overcome adoption barriers.

By identifying triggers for ergonomic intervention, the framework enables SMEs to act preemptively rather than reactively. To enable effective evaluation of the impact of ergonomic interventions on productivity, adaptable metrics, drawn from the literature, have been aligned with the triggers. These metrics include cycle time, output rate, and error rate, which may be useful to assess task efficiency and operational accuracy as well as absenteeism and turnover rates, all of which may serve as indicators of workforce stability. In addition, employee satisfaction and self-reported productivity may offer valuable qualitative insights into worker engagement and perceived performance.

The integration matrix offers a structured, step-by-step pathway for embedding ergonomics in core business processes. Organised to use participatory design, simplified assessment tools, and WTs, the matrix supports the systematic implementation, evaluation, and continuous improvement of ergonomic interventions. It is aligned with ISO 45001:2018 and ISO TR 12295:2014 principles to ensure both international relevance and local adaptability.

Furthermore, the study engaged directly with the contextual realities of South African SMEs by mapping out specific organisational and regulatory barriers to the adoption of ergonomics. The framework's third phase responds to these barriers with tailored resolutions and accessible resources, which range from local funding mechanisms and training programmes to participatory design tools and technology-sharing models.

Ultimately, this research should contribute a practical, scalable, and context-sensitive framework that empowers South African SMEs to enhance their productivity through ergonomic innovation. It challenges the prevailing notion that ergonomics is a luxury reserved for large enterprises, showing instead that, even in resource-constrained environments, ergonomics can be a strategic enabler of sustainable growth. This research bridges the gap in research by providing a practical framework for integrating ergonomics advances into South African SMEs.

6. LIMITATION OF THE STUDY

The following research shortcomings have been identified:

• The study relied solely on secondary data.

• This framework has not been tested in practice in the South African SME environment.

• The framework remains general, and is not tailored to specific industries.

7. FUTURE RESEARCH

The following areas for future research have been identified:

• The framework should be validated through case studies or pilot implementation in South African SMEs.

• The framework should be tailored to specific industries.

REFERENCES

[1] The Banking Association South Africa. 2025. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Available at: https://www.banking.org.za/what-we-do/sme/ [Accessed on Feb 11, 2025]. [ Links ]

[2] Dul, J., Bruder, R., Buckle, P., Carayon, P., Falzon, P., Marras, W. S., Wilson, J. R., & Van der Doelen, B. 2019. A strategy for human factors/ergonomics: Developing the discipline and profession. Ergonomics, 62(3), pp. 377-395. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2012.661087 [ Links ]

[3] Mashwama, N., Aigbavboa, C., & Thwala, W. 2018. Occupational health and safety challenges among small and medium-sized enterprise contractors in South Africa. In International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics, Springer, pp 68-76. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60450-3_7 [ Links ]

[4] Christie, C. J.-A. 2012. Straightforward yet effective ergonomics collaborations in South Africa. Ergonomics in Design, 20(4), pp 39-42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1064804612455641 [ Links ]

[5] Grobelny, J. & Michalski, R. 2020. Preventing work-related musculoskeletal disorders in manufacturing by digital human modeling. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8676. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228676 [ Links ]

[6] Roopnarain, R., Dewa, M., & Ramdass, K. 2019. Use of seientific ergonomic programmes to improve organisational performance. The South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 30(3), pp 1-8. https://doi.org/10.7166/30-3-2229 [ Links ]

[7] Applied Ergonomics Conference 2025. 2025. Problem solved: The IISE podeast: Conference insights. Institute of Industrial and Systems Engineers. [Online] Available at: https://www.iise.org/AEC/ [Accessed March 25, 2025]. [ Links ]

[8] Sabino, I., Fernandes, M., Cepeda, C., Quaresma, C., Gamboa, H., Nunes, I. L., & Gabriel, A. T. 2024. Application of wearable technology for the ergonomic risk assessment of healthcare professionals: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 100(1), 103570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2024.103570 [ Links ]

[9] Noraxon USA. 2025. Biomechanics in motion: Simplifying workplace assessments. Presented at Applied Ergonomics Conference (AEC) 2025. [Online] Available at: https://www.noraxon.com [Accessed March 25, 2025]. [ Links ]

[10] Voon, S., Mohd, J., Nik Hisyamudin, M., Muhammad, Y., Jacquelyne, B., & Syazwan, I. 2018. Ergonomic assessment in small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1049(1), 012065. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1049/1/012065 [ Links ]

[11] Burgess-Limerick, R. 2018. Participatory ergonomics: Evidence and implementation lessons. Applied Ergonomics, 68(1), pp 289-293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2017.12.009 [ Links ]

[12] Govuzela, S. & Mafini, C. 2019. Organisational agility, business best practices and the performance of small to medium enterprises in South Africa. South African Journal of Business Management, 50(1), a1417. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajbm.v50i1.1417 [ Links ]

[13] Esterhuyzen, E. (2019). Small business barriers to occupational health and safety compliance. Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, 11(1), a233. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajesbm.v11i1.233 [ Links ]

[14] Zink, K. J. 2013. Designing sustainable work systems: The need for a systems approach. Applied Ergonomics, 45(1), pp 126-132, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2013.03.023 [ Links ]

[15] Ahmed, H. 2023. Human systems integration: A review of concepts, applications, challenges, and benefits. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 14(4), pp 32-45. https://doi.org/10.7176/JESD/14-4-04 [ Links ]

[16] Bridger, R. S. 2017. Introduction to human factors and ergonomics, 4th ed. CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781351228442 [ Links ]

[17] Imada, A. S. 2012. Participatory ergonomics: Past, present, and future. Journal of Human Ergology, 40(1-2), pp 85-91. https://doi.org/10.11183/jhe.40.85 [ Links ]

[18] Van Eerd, D., Munhall, C., Irvin, E., Rempel, D., Brewer, S., Van der Beek, A. J., & Dennerlein, J. T. 2016. Effectiveness of workplace interventions in the prevention of upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders and symptoms: An update of the evidence. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 73(1), pp 62-70. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2015-102992 [ Links ]

[19] Stefana, E., Marciano, F., Rossi, D., Cocca, P., & Tomasoni, G. 2021. Wearable devices for ergonomics: A systematic literature review. Sensors, 21(3), pp 777. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21030777 [ Links ]

[20] Chindove, M. & Lemmer, C. 2022. Literature review on ergonomics, ergonomics practices, and employee performance, Quest Journal of Management and Social Sciences, 4(1), pp 50-56. https://www.nepjol.info/index.php/qjmss/article/view/50322 [ Links ]

[21] Deloitte SA. 2023. Mental health and well-being in the workplace. Deloitte Global Insights. [Online] Available at: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/Life-Sciences-Health-Care/gx-mental-health-2022 [Accessed March 12, 2025]. [ Links ]

[22] Sinno, N. & Ammoun, M. 2019. The impact of ergonomics on employees' productivity in the architectural workplaces. International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology, 8(5C), pp 1122-1132. https://doi.org/10.35940/ijeat.E1157.0585C19 [Accessed on March 12, 2025]. [ Links ]

[23] Emergence Growth. 2022. Africa employee engagement outlook 2021-2022. Emergence growth report. Available at: https://emergencegrowth.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Africa-Employee-Engagement-Outlook-2021_2022-Final.pdf [ Links ]

[24] Chinyamurindi, W. T. & Mashavira, N. 2024. Job satisfaction and turnover: The role of creativity, engagement, and decent work amongst employees. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(1), a2713. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v22i0.2713 [ Links ]

[25] Hignett, S. & Darvishi, L. 2000. Rapid entire body assessment (REBA). Applied Ergonomics, 31(2), pp 201-205. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-6870(99)00039-3 [ Links ]

[26] McAtamney, L. & Corlett, E. N. 1993. RULA: A survey method for the investigation of work-related upper limb disorders. Applied Ergonomics, 24(2), pp 91-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-6870(93)90080-S [ Links ]

[27] Waters, T. R., Putz-Anderson, V., Garg, A., & Fine, L. J. 1993. Revised NIOSH equation for the design and evaluation of manual lifting tasks. Ergonomics, 36(7), pp 749-776. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139308967940 [ Links ]

[28] Duffy, V. G. (ed). 2023. Digital human modeling and applications in health, safety, ergonomics and risk management. 14th International Conference, DHM, Proceedings, Copenhagen, Denmark, July 23-28, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-35748-0 [ Links ]

[29] Lakshmi, V. V. & Deepika, J. 2020. Workplace ergonomic risk assessment (WERA) of female weavers. London Journal of Research in Science: Natural and Formal, 20(8), pp 39-53. [ Links ]

[30] OSHA. 2000. Ergonomics program management guidelines for meatpacking plants, OSHA 3123. U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Available at: Ergonomics Program Management Guidelines For Meatpacking Plants | Occupational Safety and Health Administration [Accessed on March 12, 2025]. [ Links ]

[31] ISO TR 12295. 2014. Ergonomics - Application of the new ISO standards on manual handling and application of ISO/TR 12295. International Organization for Standardization. Available at: https://www.iso.org/standard/51309.html [Accessed on March 11, 2025]. [ Links ]

[32] Kuorinka, I., Jonsson, B., Kilbom, A., Vinterberg, H., Biering-Sorensen, F., Andersson, G., & Jorgensen, K. 1987. Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Applied Ergonomics, 18(3), pp 233-237. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-6870(87)90010-X [ Links ]

[33] Robertson, M. M. & Huang, Y. H. 2006. Effect of a workplace design and training intervention on individual performance, group effectiveness and collaboration: The role of environmental control. Work, 27(3), pp 213-227. http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2006-00543 [ Links ]

[34] Kee, D. & Karwowski, W. 2007. A comparison of three observational techniques for assessing postural loads in industry. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 13(1), pp 3-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2007.11076704 [ Links ]

[35] Hasle, P. & Limborg, H. J. 2006. A review of the literature on preventive occupational health and safety activities in small enterprises. Industrial Health, 44(1), pp 6-12. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.44.6 [ Links ]

[36] David, G. 2005. Ergonomic methods for assessing exposure to risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Occupational Medicine, 55(3), pp 190-199. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqi082 [ Links ]

[37] Legg, S., Laird, I., Olsen, K., & Hasle, P. 2015. Managing safety in small and medium enterprises. Safety Science, 71(C), pp 189-196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2014.11.007 [ Links ]

[38] Colim, A., Sousa, N., Carneiro, P., Costa, N., Arezes, P., & Cardoso, A. 2020. Ergonomic intervention on a packing workstation with robotic aid: Case study at a furniture manufacturing industry. Work, 66(1), pp 229-237. doi: https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-203144 [ Links ]

[39] Eswaramoorthi, M., John, M., Arjun Rajagopal, C., Prasad, P. S. S., & Mohanram, P. V. 2010. Redesigning assembly stations using ergonomic methods as a lean tool. Work. 35(2), pp 231-240. [ Links ]

[40] Mahmood, S. Aziz, S., Zulkifli, M., & Marsi, N. 2020. Rula and Reba analysis on work postures: A case study at poultry feed manufacturing industry. Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience, 17(2-3), pp 755-764. https://doi.org/10.1166/jctn.2020.8716 [ Links ]

[41] Masahuling, A. & Saman, A. 2020. Ergonomic interventions in lighting products manufacturing plant. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 834(1), 012076. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/834/1/012076 [ Links ]

[42] Eladly, A., Abou-Ali, M., Sheta, A., & EL-Ghlomy, S. 2020. A flexible ergonomic redesign of the sewing machine workstation. Research Journal of Textile and Apparel, 24(3), pp. 245-265. https://doi.org/10.1108/RJTA-10-2019-0050 [ Links ]

[43] Carr, K. E. & Davidson, M. W. 2025. Basic microscope ergonomics, Nikon's MicroscopyU. Available at: https://www.microscopyu.com/microscopy-basics/basic-microscope-ergonomics[Accessed on March 11, 2025]. [ Links ]

[44] Dalton, K. 2019. Reducing pain and strain: The ergonomics of pipetting. Future Lab. Biocompare.com. Available at: https://www.biocompare.com/Editorial-Articles/363890-Reducing-Pain-and-Strain-The-Ergonomics-of-Pipetting/ [Accessed March 11, 2025] [ Links ]

[45] Gade, R., Chandurkar, P., Upasani, H., & Khushwaha, V. 2015. Ergonomic intervention to improve safety. International Journal On Textile Engineering and Processes, 1(3), pp 79-87. Available at: https://www.scribd.com/document/425675410/Ergonomics [Accessed March 11, 2025]. [ Links ]

Submitted by authors 31 Mar 2025

Accepted for publication 11 Jun 2025

Available online 29 Aug 2025

* Corresponding author: mukalayta@tut.ac.za

ORCID® identifiers

T.A. Mukalay: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0006-2311

J. Swanepoel: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6861-4437

T. Nenzhelele: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9730-0346