Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Scriptura

On-line version ISSN 2305-445XPrint version ISSN 0254-1807

Scriptura vol.119 n.1 Stellenbosch 2020

https://doi.org/10.7833/118-1-1686

ARTICLES

Religious intersections in African Christianity: the conversion dilemma among indigenous converts

Joel Mokhoathi

Department of Religion Studies University of the Free State

ABSTRACT

The conversion of indigenous converts to Christianity is often perceived as a linear process, which marks individuals' rebirth and assumption of a new identity as they are assimilated into the Christian fold. This simplistic view, however, seems to undermine the intrinsic technicalities that are involved in the process of conversion, particularly for indigenous converts who already embrace a unique worldview, which is different from and sometimes contradictory to the conservative Christian outlook. This paper uses a qualitative research approach in the form of document analysis to critically explore the religious intersectionalities between Christianity and African Traditional Religion (ATR), and discusses some dilemmas that are inherent in the conversion of indigenous converts. It concludes by suggesting a paradigmatic model for re-viewing and reinterpreting the coming together of Christianity and African Traditional Religion in Africa south of the Sahara, particularly in South Africa.

Keywords: African Christianity; African Traditional Religion; Conversion; Indigenous converts; Hybridity

1. Introduction

Conversion, as a transformative process, does not occur in a vacuum (Masondo 2015:93). It is significantly influenced by the "interplay of identity, politics and morality" (Hefner 1993:4). That is why social scientists continue to show interest in the notion of conversion, especially Christian conversion, as a religious experience that solidifies faith and transforms the believer's life (Staples and Mauss 1987:146). This is because conversion implies "the acceptance of a new locus of self-definition, a new, though not necessarily exclusive, reference point for one's identity" (Hefner 1993:17). This paper, therefore, critically explores the religious intersectionalities between Christianity and African Traditional Religion (ATR), and discusses some dilemmas which are inherent in the conversion of indigenous converts. A paradigmatic model according to which the intersection between Christianity and ATR can be understood and interpreted, is also suggested. This paradigmatic model rests upon the premise of hybridity rather than syncretism as a popular concept.

2. The intersection of Christianity and ATR

The developed awareness that Christianity in Africa, particularly in South Africa, has generally been merged with African Traditional Religion, does not seem to excite, and tends to generate some agitation in both conservative Christians and rigorist African religionists. The central consensus between these two religious traditions is that Christianity and ATR are a paradox and cannot therefore be reconciled (Mndende 2009:8). This perception, however, appears to controvert the nominalist view, which advocates that the two religious traditions - Christianity and ATR - are compatible and are, in fact, two related systems of thought and practice (Mlisa 2009:8). These erratic perceptions therefore appear to ground understanding and interpretation of the intersectionalities between Christianity and ATR.

In most cases, these interpretations tend to be absolute and often seem to undermine the insider view - the views of the practitioners. This means that both conservative Christians and rigorist African religionists tend to see a clear divide between Christianity and ATR, but nominal Christians often allude to a grey area, which is not necessarily acknowledged or explored by non-practitioners. In their view, Christianity and ATR are two related systems of thought and practice (Hirst 2005:4).

The opponents of this nominalist view argue that this intersection implies syncretism (Bediako 1994:14). Thus, it is argued that the syncretism of Christianity and ATR distort the originality of both systems, since the elements of one religion are expressed through the other (Hastings 1989:30-35).

What is often undermined in this debate, however, is the evaluation of how Christianity made its way into Africa. According to Ferguson (2003:115), Bosch (1991:227) and Oduro, Pretorius, Nussbaum and Born (2008:37), Christianity arrived in Africa riding on the wings of colonisation and Western civilisation.

Therefore, subversion, potency and military strength were part of this crusade (Reill and Wilson 2004:294). African converts were often obligated to accept Christianity (Chingota 1998:147). Their religious and cultural heritage was ridiculed and commonly classified as heathenism (Carey 1792:93; Brown 1970:3). They were forced to acknowledge Christianity, as early missionaries were set on destroying their cultural and religious heritage (Hoschele 2007:262). The external pressure which Christianity imposed upon the structural functioning of their society was so great that it could not simply be ignored (Mlisa 2009:9). They had to adapt, and juxtaposing Christianity and ATR was an alternative way of doing so.

3. Critiquing the intersectionality - Christianity and ATR

Initially, the intersectionality of Christianity and ATR appears to have grown out of the missionary error of not recognising the value of African traditional customs and religious systems (Willoughby 1970: xviii-xix). However, its endurance so far, even after the missionary pressure has ended, seems to beg an enquiry. It makes one wonder how this phenomenon moved beyond the stages of pretense (if it was ever used to garner social recognition, acceptance and material gains from missionaries), to a level where indigenous converts willfully and purposely prefer to juxtapose Christianity and ATR.

Could this be a new form of expression which African converts were denied during the missionary epoch, which is now manifesting in the form of the intersectionality between Christianity and ATR? Or is it the basic search for a true African Christian identity, which is generated by the search for a way in which one may truly be an African Christian within an African cultural context? If this realism is indeed a search for an Afro-Christian identity, then it is comprehensible. African Christians must try to find ways in which they may rally express their Christian identity within their cultural context.

If this comes about by trial and error, then it is also sensible - as long as they discover themselves in the process. But if this is a new form of expression, then one must enquire how this realism is lived, and how the practitioners of this reality describe it. An inside view is therefore imperative in this form of enquiry. But since this paper deals with the technicalities inherent to the conversion of indigenous converts, this inquiry will be reserved for another time.

Some scholars, however, feel that the intersection of Christianity and ATR is a form of hypocrisy, in which African people use Christianity and its symbols to revive their religious practices (De Gruchy 1990:46). But other scholars, such as Ray (1976:3), see this as an account of ignorance. Indigenous converts had no alternative means by which to resisthe influence of Christianity other than incorporating Christian values systems into their African traditional belief systems (Mbiti 1969:223). They sought to acknowledge the Christian influence without denying their cultural identity. Mugambi (2002:519-520) notes that "[o]n the one hand, they [indigenous converts] accepted the norms introduced by the missionaries who saw nothing valuable in African culture. On the other hand, the converts could not deny their own cultural identity". This implies that indigenous converts were often put in a position where they had to choose between denominational belonging and cultural identity.

Their dilemma is clear, "[t]hey could not substitute their denominational belonging for their cultural and religious heritage. Yet they could not become Europeans or Americans merely by adopting some aspects of the missionaries' outward norms of conduct" (Mugambi 2002:519-520). A reasonable solution to this dilemma was to juxtapose the two religious traditions - Christianity and ATR. This, however, was not an easy process. It required that African converts live double lives: They professed to be Christians in public but were also supporters of ATR in private (Ntombana 2015:110).

They lived this double life because early missionaries forbade them from practicing their African traditional rites and customs (Afeke and Verster 2004:50). Those who were found contravening the regulations of the missionaries were harshly and publicly disciplined (Mills 1995:153ff). Elaborating on this idea, Ntombana (2015:110) notes that in 1881 the Wesleyan Methodist clerics James Lwana and Abraham Mabula were disciplined for accepting Lobola (dowry) for their daughters. Another Methodist cleric, Nehemiah Tile, was found guilty of contributing an ox for the circumcision of the Tembu paramount heir, Dalindyebo. After this incident, Nehemiah Tile is said to have withdrawn from the Methodist Church (Mills 1995:153ff). This indicates that the missionary campaign was hostile towards the African cultural and religious heritage. It sought to replace traditional norms with Western cultural values (Jafta 2011:61). That is probably why scholars such as Prozesky (1991:39) note that:

It is important for Christians to remember that in the experience of black people, the gospel arrived here in tandem with deeply destructive political and commercial forces which have succeeded in making two of South Africa's indigenous faiths, those of the Khoikhoi and the San, extinct within our boarders, have destroyed all the once-independent polities of the pre-European period and massively exploited all their survivors, and have extensively eroded the ancestral faiths of the Bantu-speaking peoples.

Therefore, when critiquing the intersectionality between Christianity and ATR, scholars ought to consider the historical context from which this realism was born: It is the direct consequence of the supremacy of Christianity over indigenous religions in Africa. As Lado (2006:8) contends, Christianity was ethnocentric. It was characterised by the dominance of Western culture over African cultures. This ethnocentric attitude elevated the status of Christianity, but at the expense of indigenous religions - such as ATR.

Indigenous religions, like those of the Khoikhoi and San, were massively undermined and ultimately extinguished (Prozesky 1991:39). The spirituality of indigenous people was seen as barbarism or heathenism (Bediako 1992:225). Their conversion to Christianity was viewed as a form of "liberation from a state of absolute awfulness [...]." (Hastings 1967:60). But, as Ray (1976:3) contends, these early missionary perceptions of African people were "based on inaccurate information and cultural prejudice".

Early missionaries should have attempted to understand the cultural and religious context of indigenous people. William (1950:15) appears to have understood the importance of this compromise:

The evil of institutions "often lies on the surface while the good only becomes apparent as the result of prolonged and painstaking investigation": but "the more a missionary knows his people, the more he finds to admire" and marvel at even in the lowliest forms of religion. It is impossible to regard the religious systems of savage and barbarous peoples as merely the work of the devil.

This implies that early missionaries hastily judged the embodiment of African traditional cultures and religious systems without proper, prolonged or painstaking investigation. As a result, they basically rejected a great number of African ideals and traditional customs. Yet scholars such as Mugambi (2002:517) note that Christianity cannot be fully expressed or adequately communicated without a cultural medium. This implies that Christianity can find expression in any cultural medium, including the African culture. In this manner indigenous converts should be allowed to experience Christianity or Christ within their cultural context.

4. Conversion as a dilemma for indigenous converts

The conversion of indigenous converts to Christianity is often seen as a linear process that marks the rebirth of an individual into the new faith and is characterised by the assumption of a new identity. But this simplistic view tends to undermine the intrinsic details inherent to the conversion of people who already possess a unique worldview, which is based on the rationality of the African traditional religious heritage and its socio-cultural norms. This worldview is different from, and sometimes appears to contradict, the conservative Christian view. The conservative Christian outlook1 places Christ at the centre of everything, whereas the ancestors play a dominant role in the African traditional worldview.

Conversion, as the "transformation of one's self concurrent with a transformation of one's basic meaning system" (McGuire 2002:73), either consolidates or challenges these worldviews. This implies that conversion has the ability to reinforce or challenge the sense of who people are and their sense of belonging within a social setting. This happens to be the case with radical transformation. Radical transformation occurs when people make a radical change through conversion to a different religious tradition and when this change affects both their self-actualisation and social affiliations (McGuire, 2002:74).

A clear example of this is when a Muslim person converts to mainstream Christianity, or vice versa, through marriage. This form of conversion has both the ability to change the sense of who people are and their sense of belonging within the social context. This is because the new identity often demands that people break away from their old or previous identity in order to fully submerge themselves within the current. This break away from the old identity may easily bring about some form of alienation from their previous community, as their new identity no longer aligns with their former way of life and traditional beliefs.

Therefore, the conversion of indigenous converts who are practitioners of ATR to Christianity has the same drastic implications for the converting individuals. They often feel obliged to break with their old self or previous identity in order to fully submerge themselves within the new Christian identity, thereby running the risk of being alienated from their traditional communities. William (1950:4), a former Bishop of Masasi in Tanzania (1926-1944), describes this dilemma as follows:

The new Christian rises from the waters of the font and goes back to his home in the village with his fellow tribesmen, men of his own nation and race: what is to be the practical relation between the new life and the old? As a catechumen he has tried to face it, but now, white from the laver of regeneration, it comes home to him with a new urgency, how shall he walk worthy of the vocation wherewith he is called? In grace he has come into a new society, his life has been raised to a new plane. But though no longer of the world, he is still in the world: he has to live out his faith in everyday life. Again and again situations will arise in which he may easily imperil his soul's new health. Custom will demand his participation with his relatives and kindred in much of which he may feel a real distrust, and yet, if he refuses to be associated with his fellow tribesmen in what are regarded as essential acts of citizenship and duties to the community, he begins to be in danger of cutting himself off completely, and at the end becoming an outcast. If his own tribe into which he was born no longer recognizes him, it is impossible for him to become a real member of any other tribe or people. He can indeed do his best to imitate the ways of another race, and another race may do their best to offer him comradeship and make him their associate to the utmost extent to which this is possible; but more than an associate he cannot become.

This denotes that, for indigenous converts, converting to Christianity often gave rise to the damning concern of breaking away from their former identity and thereby incurring the possibility of social denunciation. Thus, no matter how much indigenous converts sought to live up to Christian principles or may have embraced western precedence, when judged according to social norms and communal expectations, they quickly gained the status of outcasts. They were obligated to choose between their former lives and their new Christian identity.

If they refused to be associated with their fellow tribesmen in what was regarded as essential acts of citizenship and duties to the community, they were in danger of cutting themselves off completely from their tribes (William 1950:4). The "[t]raditionalists understood such an act as betrayal because it meant the rejection of traditional customs and practices" (Masondo 2015:94). In agreement with this, Hastings (1994:61) observes that "[i]n the nineteenth century Christian converts tended by and large to be ex-slaves, outcasts from their society, [and] refugees looking for a safe haven".

These converts were seen as amambuka2(traitors), or amagqobhoka3. In order to deal with such demands of identity loss and social denunciation, William (1950:4-5) notes that indigenous converts often considered two options:

[E]ither he will come to the missionary and ask for guidance, what he may do and what he may not do; or, if his conscience is only barely awakened or his faith has not led to a true conversion of heart, he will acquiesce too easily in the ways of the old life and lapse from religion, behaving at times as barely more than a baptized heathen, losing his sonship in slavery to the old life.

According to this first option, the indigenous convert would go to the missionaries for guidance on "what to do" or "what not to do". This involved the verbal transmission of Christian teachings and ethical guidelines (Ray 1976:5). In order to demonstrate their commitment and sincerity to the new Christian faith, they were expected to make public declarations of faith and had to exchange their indigenous names for Christian ones. According to Ntombana (2015:109), Christian names like "John, Joseph and Timothy" were given to them to reflect their new Christian identity. They were also expected to uphold all the principles and values of western culture - such as education, clothing, behaviour, etc. They were kept under close scrutiny not to disobey the teachings and guidelines of the missionaries (Matobo, Makatsa and Obioha 2009:15). Those who appeared to contravene the teachings and guidelines of the missionaries were suspended from the church (Ray 1976:5). They were "only allowed back to the Church after undergoing the church ritual of repentance and cleansing, which included public confession and assurance that they would not do it again" (Ntombana 2015:109).

This made some indigenous converts choose the second option - "acquiescing too easily in the ways of the old life and lapsing from religion [Christianity], behaving at times as barely more than a baptized heathen, losing his sonship in slavery to the old life" (William, 1950:5). This so-called "lapsing from religion" was characterised by the

Willoughby (1970:xix) rightly states that "[t]o cut a man completely away from the heritage that his ancestors left him, the mental and spiritual environment of his earlier years, would be to sever him from all that he has hitherto held sacred". In order to avoid this form of alienation from the heritage of their ancestors, indigenous converts resorted to the secret practice of the ATR. As Mndende (2009:1) remarks, they resolved to "sit on the fence", becoming Christians in public, but supporters of ATR in private. This gives the impression that indigenous converts were pressured into incorporating Christian values systems into their African religious and socio-cultural value systems.

These effects, however, are usually less drastic with consolidation (McGuire 2002:74). Consolidation is another form of conversion which entails the consolidation of an already existing identity and its meaning system with another similar religious identity. For instance, this happens when a Roman Catholic church member converts to an Anglican church member. These two religious traditions are similar and convey corresponding systems of meaning and belief. In this regard, consolidation does not challenge, but re-enforces identity.

But among indigenous converts to Christianity, the most common form of conversion is radical conversion which radically challenges the way they perceive themselves and their personal belonging within their society. In order to avoid this form of disorder, indigenous converts often tended to intersect Christianity and ATR, thereby blending the two religious systems.

This two-way process of blending and borrowing from one religious tradition to another is generally perceived as "hybridity" (Spielmann 2006:1). The process of hybridisation is by nature unapologetic and intentional (Müller 2008:1), whereas that of "syncretism" tends to suggest "the blending of foreign, non-Christian elements with (putatively 'pure', 'authentic') Christian beliefs and practices" (McGuire 2008:189).

5. Hybridisation as a developing paradigmatic model

The concept of religious "hybridity" is an ingenious metaphor to describe the African religious discourse. This is because the concept of hybridity denotes the socio-cultural exchange of various traditions from one group to the other (Bohata 2004:129). Scholars such as Spielmann (2006:1) note that "[h]ybridity has become a term commonly used in cultural studies to describe conditions in contact zones where different cultures connect, merge, intersect and eventually transform".

Hybridisation therefore denotes "the two-way process of borrowing and blending between cultures, where new, incoherent and heterogeneous forms of cultural practices emerge in translocating places - so-called third spaces" (Spielmann 2006:1). Cieslik and Verkuyten (2006:78) further note that hybridity is "predominantly used to describe cultural phenomena and identities", and this paradigmatic approach is relevant to the study of indigenous cultures.

Unlike Cieslik and Verkuyten (2006:78), who emphasise that hybridity refers "to the different lifestyles, behaviours, practices and orientations that result in multiple identities", I prefer Spielmann's description (2006:1) of hybridity as "a term [that is] commonly used in cultural studies to describe conditions in contact zones where different cultures connect, merge, intersect and eventually transform", because the coming together of various cultural traditions does not automatically imply the assumption of multiple identities, as Cieslik and Verkuyten (2006:78) suggest.

But hybridity can denote the consolidation of identity by incorporating or supplementing certain external components of culture which do not fully find adequate expression within the immediate cultural tradition. Therefore, the notion of hybridity features strongly where two or more cultural or religious traditions intersect and result into an altogether new hybrid. Homi Bhabha (1994: 211) describes this process in the following manner:

[T]he importance of hybridity is not to be able to trace two original moments from which the third emerges, rather hybridity [...] is the "third space" which enables other positions to emerge. This third space displaces the histories that constitute it, and sets up new structures of authority, new political initiatives, which are inadequately understood through received wisdom.

African Christians often fall into this category. They often espouse their African worldviews to supplement their Christian beliefs. For instance, cultural elements like witchcraft, oohili/thokolosi4, or ukuthwetyulwa5, are often undermined by mainstream Christianity, whereas these are taken seriously in African religion. Prayers are sometimes simply not enough to protect people against these, so they use charms or fetishes as additional means of protection. These protective elements do not find an interpretive paradigm within the Christian context, hence it is often difficult for Christians to understand the dynamics of African spirituality and mysticism. They cannot easily tap into African worldviews, which exist outside the scope of the Christian system, in order to understand these dynamics.

Thus, some traditional components of African cosmology are essential and necessary for African Christians to supplement the expression of Christianity within the African context. Fasholé-Luke (1978:366), for instance, notes that African theologians have begun to demonstrate "that the African religious experience and heritage were not illusory, and that they should have formed the vehicle for conveying the Gospel verities to Africa". These theologians argue that it is the rehabilitation of the African cultural and religious heritage that may regain the self-respect of Africans (Fasholé-Luke 1978:366).

Some African scholars strongly argue that in this reconstructive process the coming together of Christianity and ATR should not be categorised as "syncretism" (Mokhoathi 2017:4-5). This is because many Christian theologians still consider the dialogue between Christianity and ATR as a step towards syncretism (Adamo 2011:16). According to this perception the syncretising of Christianity and ATR denotes the corruption of Christianity. On the other hand, the notion of hybridity seems "to evoke an unapologetic sense oí blending, whereby two different traditions contribute in roughly equal measure to a new cultural/religious product" (Müller 2008:1).

I am of the opinion that this is where constructive dialogues should be based with regards to the merging between Christianity and ATR. African Christians must be empowered to find ways in which to authentically express and experience their Christian identity within their cultural context. This should evoke an unapologetic sense of blending, whereby two different traditions - the Christian and the African - contribute in equal measure to facilitate a new socio-cultural and religious end product. This end product, however, should be measured against and founded on solid biblical hermeneutics, which uphold scriptures as the standard critique of culture and its traditional practices.

In this sense, no cultural traditions which contravene the authoritative voice of scriptures, no matter how viable, may be considered or acknowledged. The scriptures must serve as a filter for indigenous customs and practices that may produce a conducive environment for African converts to experience Christianity within their cultural context. The seamless model of hybridity therefore appears to be a constructive paradigm in which to base and interpret the coming together of Christianity and ATR.

6. Conclusion

It is clear that conversion, as a transformative process, does not occur within a vacuum. Rather, it occurs within a socio-cultural and/or religious context as a result of which the converting individual already possesses a particular worldview. This worldview may be consistent with or different from (and sometimes contradictory to) the new worldview being undertaken. The conversion of indigenous converts to Christianity often mirrors the latter rather than the former situation. The former refers to the consolidation of identity through conversion, whereas the latter pertains to the alteration of identity through radical transformation. Radical conversion has the ability to drastically challenge the way converts perceive themselves and how they belong in society, thereby giving rise to issues such as identity crises or internal conflicts. These are inherent complexities of conversion. Against this background, the linear approach, which tends to characterise conversion as rebirth and the assumption of a new identity, seems to be too simplistic. It tends to undermine the dilemmas that are inherent in the conversion of indigenous converts. This is because the old identity often does not dissipate but tends to be incorporated into the new Christian identity. Therefore, this form of intersectionality is complex and needs to be re-evaluated. Hence a new paradigmatic model, which is based on the premise of hybridity, may be useful for the exploration of such an intersectionality.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adamo, D.T. 2011. Christianity and the African Traditional Religion(s): The postcolonial round of engagement, Verbum et Ecclesia 32:1 -10. [ Links ]

Afeke, B. and Verster, P. 2004. Christianisation of ancestor veneration within African Traditional Religions: An evaluation, In die Skriflig 38(1):47-61 . [ Links ]

Bediako, K. 1992. Theology and identity: The impact of culture upon Christian thought in the Second Century and modern Africa. Oxford: Regnum Books International. [ Links ]

Bediako, K. 1994. Understanding African theology in the 20th Century, Themelios 20:14-20. [ Links ]

Bhabha H. 1994. The location of culture. London: Routledge Publications. [ Links ]

Bohata, K. 2004. Post-colonialism revised: Writing Wales in English. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. [ Links ]

Bosch, D.J. 1991. Transforming mission: Paradigm shifts in mission theology. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Brown, W.H. 1970. On South African frontier: The adventures and observations of an American in Mashonaland and Matabeleland. New York: Negro University Press. [ Links ]

Carey, W. 1792. An enquiry into the obligations of Christians, to use means for the conversion of the heathens. Didcot, Oxfordshire: Baptist Missionary Society. [ Links ]

Chingota, F. 1998. A historical account of the attitude of Blantyre Synod of the Church of Central Africa Presbyterian towards initiation rites. In James L. Cox (ed.), Rites of passage in contemporary Africa: Interaction between Christian and African Traditional Religions. Cardiff, UK: Cardiff Academic Press, pp. 146-55. [ Links ]

Cieslik, A. and Verkuyten, M. 2006. National, ethnic and religious identities: Hybridity and the case of the Polish Tatars, National Identities 8(2):77-93. [ Links ]

De Gruchy, J.W. 1990. The church struggle in South Africa. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Fashole-Luke, E.W. 1978. Christianity in independent Africa. London: R. Collings Publications. [ Links ]

Ferguson, N. 2003. Empire: How Britain made the modern world. London: Allen Lane Publications. [ Links ]

Hastings, A. 1976. African Christianity. London: Geoffrey Chapman. [ Links ]

Hastings, A. 1989. African Catholicism - An essay in discovery. London: SCM Press. [ Links ]

Hastings, A. 1994. The church in Africa 1450 - 1950. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Hefner, R.W. 1993. Introduction: World building and the rationality of conversion. In Robert. W. Herfer (ed.), Conversion to Christianity: Historical and anthropological perspectives on a great transformation. Oxford: University of California Press, pp. 3-46. [ Links ]

Hirst, M.M. 2005. Dreams and medicines: The perspective of Xhosa diviners and novices in the Eastern Cape, South Africa, Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology 5:1-22. [ Links ]

Höschele, S. 2007. Christian remnant - African folk church: Seventh-day Adventism in Tanzania, 1903-1980. Boston, MA: Brill Publication. [ Links ]

Jafta, L. 2011. The Methodist Church of Southern Africa: The establishment and the expansion of the mission. In Itumeleng Mekoa (ed.), The journey of hope: Essays in honour of Dr. Mmutlanyane Stanley Mogoba. Cape Town: Incwadi Press, pp. 56-65. [ Links ]

Lado, L. 2006. The Roman Catholic Church and African religions: A problematic encounter, The Way 45:7-21. [ Links ]

Masondo, S. 2015. Indigenous conceptions of conversion among African Christians in South Africa, Journal for the study of Religion 28(2):87-112. [ Links ]

Mathema, Z.A. 2007. The African worldview: A serious challenge to Christian discipleship, Ministry, International Journal for Pastors 79:5-7. [ Links ]

Matobo, T.A, Makatsa, M. and Obioha, E.E. 2009. Continuity in the traditional initiation practice of boys and girls in contemporary Southern African society, Studies of Tribes and Tribals 7:105-13. [ Links ]

Mbiti, J.S. 1969. African religions and philosophy. London: Heinemann Educational Books. [ Links ]

Mbiti, J.S. 1992. African religions and philosophy (rev. ed.). London: Heinemann Educational Books. [ Links ]

McGuire, M.B. 2002. Religion: The social context. London: Wadsworth Thomson Learning. [ Links ]

McGuire, M.B. 2008. Lived religion: Faith and practice in everyday life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Mills, W.G. 1995. Missionaries, Xhosa clergy and the suppression of traditional customs. In C. Bredenkamp and Robert J. Ross (eds), Missions and Christianity in South African history. Johannesburg, RSA: Witwatersrand University Press, pp. 153 -72. [ Links ]

Mlisa, N.L. 2009. Ukuthwasa, the training of Xhosa women as traditional healers. PhD dissertation, University of the Free State. [ Links ]

Mndende, N. 2009. Tears of distress: Voices of a denied spirituality in a democratic South Africa. Dutywa, RSA: Icamagu Institute. [ Links ]

Mokhoathi, J. 2017b. From contextual theology to African Christianity: The consideration of adiaphora from a South African perspective, Religions 8(266):1-14. [ Links ]

Mugambi, J.N.K. 2002. Christianity and the African cultural heritage. In Jesse N.K. Mugambi (ed.), Christianity and African culture. Nairobi: Acton Publications, pp. 516-42. [ Links ]

Müller, R. 2008. Rain rituals and hybridity in South Africa, Verbum et Ecclesia JRG 29(3):819-31. [ Links ]

Ntombana, L. 2015. The trajectories of Christianity and African ritual practices: The public silence and the dilemma of mainline or mission churches, Acta Theologica 35:104-19. [ Links ]

Oduro, T., Pretorius, H., Nussbaum, S. and Born, B. 2008. Mission in an African way: A practical introduction to African instituted churches and their sense of mission. Wellington: Christian Literature Fund and Bible Media Publication. [ Links ]

Prozesky, M. 1991. The challenge of other religions for Christianity in South Africa, Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 74:35-45. [ Links ]

Ray, B.C. 1976. African religions: Symbol, ritual and community. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc. [ Links ]

Reill, P.H. and Wilson, E.J. 2004. Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment. New York: Facts On File Incorporated. [ Links ]

Sanneh, L. 1993. Encountering the West: Christianity and the global cultural process - the African dimension. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Schineller, P. 1990. A handbook on inculturation. New York: Paulist Press. [ Links ]

Spielmann, H. 2006. Hybridity: Arts, science and cultural effects, Leonardo 39(2):23- 39. [ Links ]

Staples, C.L. and Mauss, A.L. 1987. Conversion or commitment? A reassessment of the Snow and Machalek approach to the study of conversion, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 26(2):133-47. [ Links ]

Stromberg, P.G. 2008. Language and self-transformation: A study of the Christian conversion narrative. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

William, V. 1950. Christianity and native rites. London: Central Africa House Press. [ Links ]

Willoughby, W.C. 1970. The soul of the Bantu: A sympathetic study of the magico- religious practices and beliefs of the Bantu tribes of Africa. Westport, Connecticut: Negro University Press. [ Links ]

1 The phrase "conservative Christian outlook" is used in this paper to refer to Christians who tend to follow conservative values, in contrast to liberal Christian viewpoints. The label "conservative", however, does not necessarily imply the acceptance of all basic conservative values. Rather, it designates Christian groups who are more traditional than other members of the same faith family.

2 Among amaZulu tribes, Christian converts were referred to as amambuka (traitors) because they were seen to be rejecting the ways of their forefathers, as well as their community. They literally ran away and settled in mission stations (see Sibusiso Masondo 2015:94).

3 Among amaXhosa tribes, a Christian convert was referred to as igqobhoka. This term has no direct translation into English. But Mndende (1998:9) describes igqobhoka as a container with a hole in it, that is letting out what is good and valuable, while letting in what is evil and undesirable. She argues that amagqobhoka are untrustworthy because they serve two masters - Christ and the ancestors.

4 There is no direct translation of this term into English. But oohili/thokolosi may be described as dwarf-like creatures that are used by witches to pursue evil ends, or to cause harm to other people, including their enemies.

5 There is no direct translation of this term into English. But ukuthwetyulwa may imply abduction through witchcraft to alien places, such as forests, rivers, deserts, or mountains, while family members assume that the victim has died.

ARTICLES

The reception and delivery of the oracle in Revelation 13:9-10

David Seal

Cornerstone University Grand Rapids, USA

ABSTRACT

This study will examine how the oracle in Revelation 13:9-10 might have been regarded by the original audience as it was recited by the lector to each of the seven churches. The oral cultural context from which it originated decisively shaped the oracle's form and content. That oral cultural context will be considered in this analysis. The investigation will be conducted in three steps. First, this essay will argue that in the recitation of Revelation, the assemblies in Asia Minor would have perceived the following: the author's presence, his authority as a prophet, and the divine presence. Second, it will demonstrate that in hearing the oracle in Revelation 13:9-10, the congregants would have heard John's voice and accepted the prophet's words as caring and authoritative. Finally, the poetic nature of the oracle will be examined for its ability to foster a sense of the semantic divine presence. Consequently, when the prophecy was read aloud, it may have nurturedfeelings of awe, reverence, and respect for God in the listeners.

Keywords: New Testament prophecy; Orality; Poetry; Revelation, book of

1. Introduction

Most studies on the phenomenon of early Christian prophecy, as described in the New Testament, address either one or a combination of the following (e.g. Ellis 1978; Hill 1979; Gillespie 1985; Callan 1985; Tibbs 2007; Aune 1983; Boring 1991): 1) They attempt to determine what the prophets were doing by assigning a definition to their activity; 2) they endeavour to describe the function of the prophets; or 3) they investigate the nature of the oracles. However, these studies have not closely examined how specific oracles, embedded in the New Testament books, would have been delivered once they arrived at their intended destinations, or how they would have been understood by the communities that heard them recited.1 The oral cultural context from which they originated decisively shaped their form and contents and must, therefore, be considered in any analysis.

I am grateful for the comments and suggestions received from the anonymous reviewers for Scriptura.

This study will address this gap by examining how the oracle recounted in Revelation 13:9-102 might have been regarded by the original audience.3 In part, this study is concerned with determining the ancient understanding of the authoritative force of John's prophetic words. This investigation will be conducted in three steps. First, following a summary of the socio-historical situation of the churches in Asia Minor, this essay will argue that in the recitation of Revelation, the assemblies would have perceived the following: the author's presence, his authority as a prophet, and the divine presence. Second, it will demonstrate that in hearing the oracle in Revelation 13:9-10, the congregants would have heard the prophetic voice of John and accepted his words as caring and authoritative. Finally, the poetic nature of the oracle will be examined for its ability to foster a sense of the semantic divine presence. Consequently, when the prophecy was read aloud, it may have nurtured feelings of awe, reverence, and respect for God in the listeners.

2. The socio-historical situation of Revelation

What follows is a brief summary of the socio-historical situation of the author and the members of the seven churches receiving Revelation. The discussion will provide important background for understanding the significance of the prophetic oracle for John's listeners.

Recent scholarship claims that a crisis setting for Revelation is appropriate given that apocalypses emerge out of a critical situation (Boxall 2006:12; Collins 1984:137; Osborne 2002:11; Mounce 1997:3). Evidence in the book and from external sources suggests that the seven churches in Asia Minor faced major economic, political, and social issues. It is likely that there was pressure in the commercial arena for Christians to submit to pagan worship practices. For example, every craftsman and trader had the opportunity to belong to the relevant guild. These guilds included practices like sacrificing to a pagan god (and likely to the emperor as well) and participation in a common meal dedicated to a pagan deity (Kraybill 1996:196). In order to survive in the international marketplace, it was essential to join trade guilds. It would have been a compromise of a Christian's faith to participate in the activities of these organisations. The Nicolaitans (Rev 2:6, 15) seem to have been a group that corrupted the church by suggesting compromise with the culture of the day. Rather than worshiping God alone, they said it was appropriate to engage in cultural activities of the empire. The Nicolaitan practices were linked with Balaam (Rev 2:14-15) and Jezebel (Rev 2:20-23). One of the sins found in both the Balaam narrative and the Jezebel narrative (1 Kgs 16:31) is idolatry. Therefore, it is probable that the Nicolaitans encouraged the church in Ephesus to accommodate the pagans by participating in their practices (Osborne 2002:120-121). To counter the Nicolaitan's instructions, Revelation discloses the rewards for those who remain faithful despite the pressure to compromise (e.g. 6:9-11; 7:9-17).

Christians in Asia Minor also experienced harassment from their Jewish neighbors. Informing the local authorities of Christian nonparticipation in emperor worship may have been one form of harassment enacted by some Jews. Another could have been pointing out to the Roman establishment that despite the apparent similarities between the two groups, the Christians were not, in fact, Jews, and therefore, were not exempt from emperor worship, as were the Jews.4 In the early years of the church, Rome did not see a distinction between Christianity and Judaism. But later Jews antithetical to Christianity could act as informants for Rome against Christians. This scenario might explain the references to "the synagogue of Satan" in Rev 2:9 and 3:9 (DeSilva 1992:279).

In addition to external pressures to compromise, the letters to the seven churches reveal that the communities faced internal strife. These problems emerged in the form of false prophets whose teaching threatened to weaken community boundaries (Balaam, Rev 2:14, the Nicolaitans, Rev 2:6, 15, and Jezebel, Rev 2:20). As noted, it is likely the Nicolaitans (Rev 2:6) falsely "redefined apostolic teaching" so Christians could feel comfortable participating in the practices of pagan organisations (Beale 1999:30).

John's community was experiencing various forms of stress such as ostracism and social contempt. They likely faced some local persecution, but not widespread state persecution. The Christian community felt threatened and insecure and would have been subject to religious as well as social stress. This stress was produced by the externally enforced worship of the Roman emperor, with social and economic sanctions applied against nonconformists.

3. Reception: Authorial presence

John, who was confined5 to Patmos (Rev 1:9), wrote and sent correspondence to the seven churches in Asia Minor,6 where a lector stood before each community and recited the letter (Rev 1:3; 2:1, 8, 12, 18; 3:1, 7, 14).7 The letter acted as a substitute for face-to-face communication (cf. Cicero, Att. 8.14.1; 12.53; Seneca, Ep. 75.1), which would presumably have taken place if John was physically present at the congregations. Written correspondence, as with other literature in the 1st century, was often read out loud by the recipient or by another literate individual on behalf of the recipient. While low literacy rates contributed to the popularity of oral recitation, even highly literate persons were accustomed to listening to passages read out loud, especially when the availability of texts was limited (e.g. Pliny, Ep. 9.34). Seneca articulated the benefit of listening to something recited, even if a person was fully literate, when he asked and answered, '"But why,' one asks, 'should I have to continue hearing lectures on what I can read?' 'The living voice,' one replies, 'is a great help.'" (Ep. 33.9).8 The 1st century Mediterranean world was a blend of an oral and a scribal culture. It was a world familiar with writing, but still significantly, even predominately, oral.

1st century oral cultures believed that the reading of a letter created a sense of the author's tangible presence (e.g. Seneca, Ep. 40.1). The letter was considered by some ancient rhetorical theorists as one half of a conversation or a replacement for dialogue (e.g. Demetrius, Eloc. 223; Cicero, Fam. 12.30.1). Seneca conveyed this notion when he wrote: "Whenever your letters arrive, I imagine that I am with you, and I have the feeling that I am about to speak my answer, instead of writing it" (Seneca, Ep. 67.2).9 The words were a mirror of their spoken counterpart, letting the absent author come to life (Fögen 2018:61). The author was regarded as concretely present in the reading or hearing of his letter, almost seen and heard through his written words. This notion is expressed in another one of Seneca's letters: "I see you, my dear Lucilius, and at this very moment I hear you; I am with you to such an extent that I hesitate whether I should not begin to write you notes instead of letters. Farewell." (Seneca, Ep. 55.11:371, 373)10

Like these secular letters, there is a significant amount of oral/aural language in New Testament epistles, suggesting an ongoing conversation between the author and the recipients of the letters.11 For example, James exhorts his audience to "listen, my beloved brothers and sisters" (Jas 2:5). The author of Hebrews uses language that stresses the actions of speaking, which are appropriate to persons engaged in a conversation (e.g. Heb 5:11; 6:9; 9:5). Both Jesus and John repeatedly urge the audience to "listen" to or "hear" what the Spirit is saying to the churches (e.g. Rev 2:7, 11, 17, 29; 3:6, 13, 22;

13:9).

John's epistle to the congregations in Asia Minor served as a substitute for his personal presence.12 The individuals reciting the epistle effectively eliminated the distance in time and space between the author and the reader/audience, giving John's words real immediacy. In the oral/aural experience of the hearers, the voice that was heard within the assembly was not only a text but was at the same time the voice of the lector and the voice of John. John was not present in any mystical way but was in attendance by means of his voice.

4. Reception: A prophetic presence

In several New Testament documents it is apparent that the authors believed they had received an authoritative divine message and were communicating these prophetic words in writing to various church assemblies. For example, Paul tells the Thessalonian community "with a word of the Lord" (έν λόγω κυρίου) what will happen to the Christians who had died before the hoped-for return of Jesus (1 Thess 4:15). Also, in Paul's statement in 2 Corinthians 13:2 - 3: "Since you desire proof that Christ is speaking... ", λαλοΰντος (speaking) is a present tense participle, communicating that Christ is speaking through Paul even as he now speaks to them through the reading of the letter. The author of Hebrews also believed his discourse was an extension or form of God's own speech. He indicates that he expects his sermon to function with the power and authority of God's own word: "See to it that you do not refuse the one who is speaking; for if they did not escape when they refused the one who warned them on earth, how much less will we escape if we reject the one who warns from heaven!" (Heb 12:25).13 The audience is hearing God's voice in the moment of the delivery of the sermon. Finally, John was a Spirit-endowed prophet, called to communicate the words of God to the seven churches in Asia Minor (Rev 1:1 -2; 1:7; 22:6). This language conveys that not only were the recipients receiving correspondence from John or Paul, but from God or Christ, who had conveyed the communication to a divine envoy.14

The individuals who received messages from God or Christ and were commissioned to deliver the oracles were to be viewed and treated by the members of the church as divinely authorised agents. Agents or messengers would have possessed some of the comprehensive authority delegated to them by their commissioners (Derrett 2005:55). In the Greek world, heralds were sacred and under the divine protection of Hermes, the divine herald (Hesiod, Theog. 939; Homer, Od. 12.390). The sacred and protected nature of heralds was also respected amongst the Romans, who recognised the essential nature of the protection (7he Digest of Justinian 50.7.18; Watson 2009:436). One of the great maxims of the Jewish law of agency was that a man's agent was like himself (b. Hag. 1:8, IV.1.C; Derrett 2005:52). The person commissioned was always the representative of the man (or God) who authorised the commission.15 Jesus likely had this law of agency in mind when he spoke to his disciples: "Whoever listens to you listens to me, and whoever rejects you rejects me, and whoever rejects me rejects the one who sent me" (Luke 10:16).16 Thus, when the language in Revelation indicates that the author is conveying a divine message, not only is the lector giving voice to John, but he is also invoking the presence of the divinely commissioned prophetic messenger.

5. Reception: Divine presence

While the congregations heard the voice of the prophet John through the lector, they actually heard far more, as the prophet became a surrogate for God or Christ as he delivered a divine oracle (e.g. Rev 1:7-8; 13:9-10).17 So, as the lector personified the prophet, he also represented the presence of God or Jesus in the community.18 Ancient written documents from various levels of leadership carried a sense of the presence of the ruler in epistolary form (Doty 2014:6).

Timothy Ward's (2009) work helps to explain how the divine presence might have been conceived by a 1st century audience upon hearing the prophetic announcement. Ward (2009:60-67) argues that God is semantically present when a person hears (or reads) God's words. He claims that Scripture indicates an "astoundingly close relationship between God as himself and the words (spoken or written) through which he speaks" (2009:26). To support this assertion, Ward (2009:26-32) cites, amongst other examples, Adam and Eve's disobedience to God's spoken command and the ensuing punishment. Their disregard of his spoken order to not eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil result in a fractured relationship with God himself, as they are sent out of his presence in the Garden (Gen 2:17; 3:24; Ward 2009:26-27). In another example, the Lord's anger is aroused when Uzzah irreverently touches the ark that houses the words of God inscribed on the tablets (2 Sam 6:7). According to Ward (2009:29-30), Uzzah is struck dead instantly because God is represented in the ten words or commandments inscribed on the tablets in the ark to such an extent that he is, in some sense, present in those words. For Ward (2009:66), God has so identified himself with his words that whatever someone does to God's words (whether it is to obey, to disobey, or to treat with disrespect, etc.) they do directly to God himself. God has chosen to use words as a fundamental means of revealing himself to humanity - though not exhaustively. God reveals himself by being semantically present to readers or listeners, as he promises, warns, rebukes, reassures and so on in Scripture.

When God or Jesus (or any person) promises, warns, rebukes, or reassures (or speaks any other performative verb) they are executing what speech-act theorists call an illocutionary act.19 John Austin's book (1975) on speech-act theory provides ways for linguists to think about words as actions, or performatives. To denote the effect or intention of an illocutionary act, Austin uses the word "perlocutions". The term perlocutions refers to how "saying something can bring about certain consequential effects upon the feelings, thoughts, or actions of the audience, or of the speaker, or of other persons" (Austin 1975:101). An illocutionary act is achieved in saying something, while a perlocutionary act is achieved by saying something. For example, a person performs an illocutionary act by saying "the toaster is hot". He or she is verbalising a warning. The goal, however, of giving this warning, is to persuade anyone in the vicinity of the toaster to act with caution and thus avoid getting burned. The goal of the statement is labelled a perlocutionary act. In this sense, words can be viewed "like servants dispatched to do the bidding of their master" (Caird 2002:21).

People (and God) speak to bring about various outcomes or effects, or to accomplish specific purposes. Speech-act theory reaffirms the interpersonal nature of textual communication. God, rather than a text, is promising, warning, rebuking, and reassuring humanity. Perlocutions may also operate through delegation (Caird 2002:25). When a person encounters the words of an Old or New Testament prophet, he or she is in direct contact with God's words - his semantic presence.20 Thus, the public reader stood in the place of the prophet John and made both him and God present. The prophet was more than God's representative for, in "the moment of delivery of the prophecy he was an active extension of God's personality and as such, was God in person" (Myers and Freed 1966:50). Subsequently, we will examine how a specific prophetic word from John to the churches may have been expressed.

6. Delivery: A compassionate and authoritative word from John (Rev 13:910)

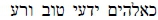

Following the vision of the beast who wages war against the church, and who likely was the representative of the Roman Empire, is a prophetic proclamation formula or a call for attention: "If anyone has an ear, let him hear" (Rev 13:9; Aune 1983:282). Here, without warning, anyone listening to the lector is abruptly addressed in the text. The formula is similar to those that open many Old Testament prophetic speeches (e.g. Isa 7:13, 28:14; Jer 2:4). In the Iliad, Zeus makes use of the call for attention formula: κέκλυτέ μευ, πάντες τε θεοί πασαί τε θέαιναι ("Hear me, all you gods and goddesses"; Homer 1925: 340-341). The call for attention formula suggests that the poetic saying that follows, is of oracular nature (Aune 1983:282).

If anyone has an ear, let him hear.

If anyone [is destined] for captivity, into captivity he goes.

If anyone kills with the sword, by the sword he must be killed.

Here is a call for the endurance and faith of the saints. (Rev 13:9-10)21

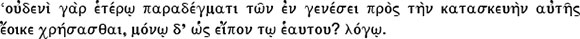

The oracle is arranged in two parallel lines. It appears to be formulated in close association with Jeremiah 15:2 LXX and 43:11 LXX (Rev 13:10a). A concluding formula articulates a call for Christians to endure persecution, and is likely the seer's own words rather than part of the divine message (Rev 13:10b; Aune 1983:282).

The difficulties in this text have produced multiple textual variants, providing evidence that scribes found the original passage quite problematic.22 At issue is the identity of who is taken captive and killed, and by whom these deeds are done. Craig Koester (2014:587-588) believes the saying has a double meaning.23 First, the warning pertains to the faithful, who may lose their freedom and lives if they refuse to worship the beast. Second, the statement expresses the principle of retributive justice (jus talonis). As such, persecuted Christians should exercise patience because God will punish the guilty for their crimes. The concept of retributive justice and divine vengeance may have brought present comfort, hope, and encouragement to Christians who were victims of evil. Other scholars do not consider the oracle as a promise of divine punishment of the wicked but, instead, believe the warning affirms the suffering of God's people and exhorts their perseverance through it (Beale 1999:704).

It is not the point of this essay to determine the intent of the oracle. Regardless of its meaning, for the purposes of this essay it is significant that the message to the oppressed churches originated with John, a fellow victim of persecution who cared for the Christians' plight. While it was not possible for John to be with the congregations in person, his presence was felt through the reading of his letter. In the ancient world sending a letter was not a trivial matter, but a clear statement expressing the author's concern and compassion for the recipients (cf. Seneca, Ep. AdLucilius 59.1). According to Pseudo-Demetrius (Eloc. 224), a letter is "written and sent as a kind of gift". In his absence, John thought of sending a gift to those he loved - an oracle (Rev 13:9-10), providing insight into how the church should respond to its oppression.

John was not merely a compassionate brother providing good advice for Christians experiencing persecution, but also a Spirit-endowed prophet, called to communicate the counsel of Jesus and God to the seven churches in Asia Minor (Rev 1:1 - 3; 1:7; 22:6). The recipients were receiving guidance from a divine envoy in the form of a prophetic word concerning the proper view of suffering that Christians should hold,24 bolstering John's exhortation that they remain faithful to their confession regardless of the pressures to do otherwise. Next, we will consider the poetic nature of the prophetic word, which would have resulted in the lector delivering it in a manner distinct from the other voices in the text competing for the listeners' attention.25

7. Delivery: The poetic nature of the divine word (Rev 13:9-10)

In addition to the compassionate and authoritative nature of the words from John, it is also important to note that the poetic form of the oracle cultivates a sense of the divine presence. Oracles in both Testaments are often poetic with formal regularities which set them apart from prose literature.26 Citing the speech of Moses (Deut 32), Josephus noted that the poetic form is characteristic of Hebrew prophecy (Ant. 4.303).27 James Kugel (1990:5) observes certain connections between the act of prophesying in the Old Testament and the accoutrements of music making or poetry (1 Sam 10:5; 2 Kings 3:1416). John's prophetic word in Revelation 13:9-10 has several poetic features, distinguishing it from what is written before and after the instruction.

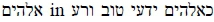

Εϊ τις εχει ούς άκουσάτω.

εϊ τις εις αίχμαλωσίαν, εις αίχμαλωσίαν υπάγει·

εϊ τις έν μαχαίρη άποκτανθήναι αυτόν έν μαχαίρη άποκτανθήναι.

Ώδέ έστιν ή υπομονή και ή πίστις των αγίων.

An initial poetic characteristic in the oracle is that the text is an example of anaphora (Demetrius, Eloc. 268; Quintilian, Inst. 9.3.30) in that successive phrases begin with the same words (εϊ τις). An additional poetic device is present in the first line of the oracle, which is written in the form of anadiplosis (Quintilian, Inst. 9.3.44-45). Anadiplosis exists when there is a repetition of a word or words which end a clause at the beginning of the next clause (εϊ τις εις αίχμαλωσίαν, εις αίχμαλωσίαν υπάγει). Anaphora and anadiplosis both contribute to the rhythm and rhyme in the oracle. Rhythm transpires with the periodic re-emergence of the same significant element or factor. Pseudo-Longinus, in discussing the sublime or that which produces exalted language and has the effect of being dignified and filled with grandeur, points to the aural effects of rhythm ([Subl.] 39-42). Furthermore, rhythm could have provided auditory stability to the original hearers' already chaotic world, thereby minimising their anxiety (Myers and Freed 1966:43).

The oracle's rhythmic poetic style may have been one of the characteristics that conveyed its authority. In the Hellenistic and Roman periods, the poetic form of oracles was viewed as an indication of their divine origin, because the Greeks widely accepted the divine inspiration of poetry. Socrates stated that poets "don't do what they do from wisdom, but from some natural inspiration, like prophets and oracle mongers" (Plato, Apol. 22b8-c2; 1925:125). Socrates noted about poets that: "For the god, as it seems to me, intended him to be a sign to us that we should not waver or doubt that these fine poems are not human or the work of men, but divine and the work of gods; and that the poets are merely the interpreters of the gods, according as each is possessed by one of the heavenly powers" (Plato, Ion. 534e-535a; 1925:425).28 Some of the Psalms, which are poetic by nature, contain oracles where God is addressing Israel, or the nations, or pagan deities (e.g. Ps 81:6-16, 82:2-7; Kugel 1990:6). As Robert Alter (2011:147) says, poetry is our best human model of complex and rich communication, being "solemn, weighty, and forceful". Consequently, it is appropriate that divine speech should be represented as poetry. Katie Heffelfinger (2013:38) states it another way: by setting prophetic texts in poetry, ancient Israelite prophets were "putting divine speech in special divine speech quotation marks".

Given that the style of language of the oracle is different from that which precedes or follows it, the poetic form tends to indicate a change in speaker - God is now addressing the church. The transformation in language contributes to the sense of the divine presence within the community. Oracles set in poetry help the prophet project the persona of God himself to the audience. While John is speaking as a prophet, the oracle is verbalised as the present utterance of God (or Jesus) in person - he is personally speaking and addressing the listeners (Boring 1992:336). This divine persona also increases the chances that the audience will experience a type of divine encounter as they hear the oracle recited (Heffelfinger 2013:45).29

In political, judicial, or religious settings, ancient recitations were not flat or mumbled (Meyer 2004:87). They were a marked mode of expression to be used on deeply serious occasions. Poetry, with its aesthetic component, was a marked mode of communication that could call attention to itself through expressions of rhythm, rhyme, and other poetic devices (Barr 1988:50-51). As the oracle in Revelation 13:9-10 was brought to life by the lector, the audience would have recognised its unique language, which perhaps would have alerted them to the importance of the communication, its divine origin, and the need for it to be considered dependable and binding.

Reverence and awe were likely stimulated by hearing the word from God. Jonathan Haidt (2012:28) contends that awe is usually triggered when two situations are present: first, vastness (something larger than us overwhelms us and makes us feel small), and second, our experience is not easily assimilated into existing mental structures. When people are mystified, they feel small, powerless, and passive.

Awe associated with the experience of being in the presence of an entity greater than the self, such as God, endows the being with higher status, respect and authority. A potential response of a subordinate who has perceived the characteristics of the person or deity who produced the awe, could involve heightened attention to the powerful person (Keltner and Haidt 2003:306). Endowing status to God, inspiring awe as a result of the divine voice, may have been encouraging for persecuted Christians and/or influential in motivating a faithful Christian commitment from the members of the churches in Asia Minor.

8. Summary and conclusion

This essay has demonstrated that, for the seven churches in Asia Minor, the prophetic word in Revelation 13:9 -10 would have been received simultaneously as the voice of the divinely commissioned prophet John, the divine himself, and the lector. John's letters are "voiced texts" - written with the intent of an oral proclamation. Both the human and divine speakers were made present across great distances by having the written words proclaimed by a public reader. The congregants would have heard John's voice and accepted the prophet's words as caring and authoritative. In addition, the poetic nature of the oracle, when communicated, may have fostered a sense of the semantic divine presence. Prophetic poetry mediates the divine voice as direct speech. God was not absent, but present as his voice was heard in the reading of his commanding word. Consequently, when the prophecy was read aloud, it may have nurtured feelings of awe, reverence, and respect for God in the listeners. Furthermore, the poetic style of the oracle (Rev 13:9-10) gives it a unique style when delivered, bolstering its authoritative nature.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alter, R. 2011. The art of Biblical poetry. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Aune, D.E. 1983. Prophecy in early Christianity and the ancient Mediterranean world. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

________. 1998. Revelation 6-16. Nashville: T. Nelson. [ Links ]

Austin, J.L. 1975. How to do things with words. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Harvard University. [ Links ]

Barr, D.L. 1986. The apocalypse of John as oral enactment, Union Seminary Review 40(3):243-256. [ Links ]

________. 1988. How were the hearers blessed? Literary reflections on the social impact of John's apocalypse, Proceedings of the Eastern Great Lakes and Midwest Biblical Societies 1988. Georgetown, KY: Eastern Great Lakes and Midwest Biblical Societies, pp. 49-59. [ Links ]

Beale, G.K. 1999. The book of Revelation: a commentary on the Greek text. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Boring, M.E. 1989. Revelation: Interpretation, a Bible commentary for teaching and preaching. Louisville, KY: John Knox Press. [ Links ]

________. 1991. The continuing voice of Jesus: Christian prophecy and the gospel tradition. Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press. [ Links ]

________. 1992. The voice of Jesus in the apocalypse of John, Novum Testamentum 34(4):334-359. [ Links ]

Boxall, I. 2006. The revelation of Saint John. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers. [ Links ]

Buchanan, G.W. 2005. The book of Revelation: Its introduction and prophecy. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock. [ Links ]

Caird, G.B. 2002. The language and imagery of the Bible. London: Gerald Duckworth and Co. Ltd. [ Links ]

Callan, T. 1985. Prophecy and ecstasy in Greco-Roman religion and in 1 Corinthians, Novum Testamentum 27(2):125-140. [ Links ]

Chaniotis, A. 2013. Staging and feeling the presence of God: Emotional and theatricality in religious celebrations in the Roman East. In L. Bricault and C. Bonnet (eds), Panthée: Religious transformation in the Roman Empire. Boston: Brill, pp. 169-189. [ Links ]

Cicero. Letters to Atticus, Vol. I. 1999. D.R.S. Bailey (tr.) (ed.). Loeb Classical Library 7. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

________. Letters to friends, Vol. I: Letters 1-113. 2001. D.R.S. Bailey (tr.) (ed.). Loeb Classical Library 205. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

________. Letters to Quintus and Brutus. 2002. D.R.S. Bailey (tr.) (ed.). Loeb Classical Library 462. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

Collins, A.Y. 1984. Crisis and catharsis: The power of the Apocalypse. Philadelphia: Westminster. [ Links ]

Demetrius. On style. 1995. S. Halliwell, W.H. Fyfe, D.C. Innes, W.R. Roberts (tr.). Loeb Classical Library 199. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

Derrett, J.D.M. 2005. Law in the New Testament. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock. [ Links ]

DeSilva, D. 1992. The social setting of the Revelation to John: Conflicts within, fears without, Westminster Theological Journal 54(2):273-302. [ Links ]

Doan, W. and Giles, T. 2005. Prophets, performance, and power: Performance criticism of the Hebrew Bible. New York: T. & T. Clark. [ Links ]

Doty, W.G. 2014. Letters in primitive Christianity. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock. [ Links ]

Ellis, E.E. 1978. Prophecy andhermeneutics in early Christianity. Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck. [ Links ]

Ferguson, E. 2011. Angels of the churches in Revelation 1-3: Status quaestionis and another proposal, Bulletin of Biblical Research 213:371-386. [ Links ]

Fögen, T. 2018. Ancient approaches to letter writing and the configuration of communities through epistles. In P. Ceccarelli, et al. (eds), Letters and communities, studies in the socio-political dimensions of ancient epistolography. Oxford: Oxford University, pp. 46-82. [ Links ]

Gillespie, T.W. 1994. The first theologians: A study in early Christian prophecy. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Griffiths, J.I. 2014. Hebrews and divine speech. New York: Bloomsbury T. & T. Clark. [ Links ]

Haidt, J. 2012. The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. New York: Pantheon Books. [ Links ]

Heffelfinger, K.M. 2013. More than mere ornamentation, Proceedings of the Irish Biblical Association 36:36-54. [ Links ]

Hesiod. Theogony. 2018. G.W. Most (tr.) (ed.). Loeb Classical Library 57. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

Hill, D. 1979. New Testament prophecy. Atlanta: John Knox. [ Links ]

Homer. Odyssey, Vol. I: Books 1-12. 1919. A.T. Murray (tr.). Loeb Classical Library 104. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

Homer. 1925. Iliad, Vol. II: Books 13-24. A.T. Murray (tr.). Loeb Classical Library 171. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

Josephus. Jewish antiquities, Vol. II: Books 4-6. 1930. H.St.J. Thackeray and R. Marcus (tr.). Loeb Classical Library 490. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

________. Jewish antiquities, Vol. VII: Books 16-17. 1963. R. Marcus and A. Wikgren (tr.). Loeb Classical Library 410. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

Keltner, D. and Haidt, J. 2003. Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion, Cognition and Emotion 17(2):297-314. [ Links ]

Koester, C.R. 2014. Revelation: A new translation with introduction and commentary. AB vol. 38a. New Haven; London: Yale University. [ Links ]

Kraybill, J.N. 1996. Imperial cult and commerce in John's apocalypse. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic. [ Links ]

Kugel, J.L. 1990. Poets and prophets: An overview. In J.L. Kugel (ed.), Poetry and prophecy: The beginnings of a literary tradition. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, pp. 1 -25. [ Links ]

Longinus. On the sublime. 1995. S. Halliwell, W.H. Fyfe, D.C. Innes, W.R. Roberts (tr.). Loeb Classical Library 199. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

Martin, T.W. 2018. The silence of God: A literary study of voice and violence in the Book of Revelation, Journal for the Study of the New Testament 41:246-260. [ Links ]

Meyer, E.A. 2004. Legitimacy and law in the Roman world: Tabulae in Roman belief and practice. New York: Cambridge University. [ Links ]

Mounce, R.H. 1997. The book of Revelation. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Myers J.M. and E.D. Freed. 1966. Is Paul also among the prophets? Interpretation 20:40-53. [ Links ]

Neusner, J. 2011. The Babylonian Talmud: A translation and commentary. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers. [ Links ]

Osborne, G.R. 2002. Revelation. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic. [ Links ]

Plato. Statesman, Philebus. Ion. 1925. H.N. Fowler and W.R.M. Lamb (tr.). Loeb Classical Library 164. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

________. Euthyphro. Apology. Crito. Phaedo. 2017. C. Emlyn-Jones and W. Preddy (tr.). Loeb Classical Library 36. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

Pliny the Younger. Letters, Vol. I: Books 1-7. B. Radice (tr.). Loeb Classical Library 55. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

Pliny the Younger. Letters, Vol. II: Books 8-10. 1969. B. Radice (tr.). Loeb Classical Library 59. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

Quintilian. 2002. The orator's education, Vol. IV: Books 9-10. D.A. Russell (tr.) (ed.). Loeb Classical Library 127. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

Seal, D.R. 2017. Prayer as divine experience in 4 Ezra and John's apocalypse: Emotions, empathy, and engagement with God. Hamilton Books: Lanham, MD. [ Links ]

Select Papyri, Volume I: Private Documents. 1932. A.S. Hunt and C.C. Edgar (tr.). Loeb Classical Library 266. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

Seneca. Epistles 1-65. 1917. R.M. Gummere (tr.). Loeb Classical Library 75. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

________. Epistles 66-92. 1920. R.M. Gummere (tr.). Loeb Classical Library 76. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [ Links ]

Tibbs, C. 2007. Religious experience of the pneuma. Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck. [ Links ]

Vanderveken, D. 1990. Meaning and speech acts, vol. 1: Principles of language use. New York: Cambridge University. [ Links ]

Vanni, U. 1991. Liturgical dialogue as a literary form in the Book of Revelation, New Testament Studies 37:348-372. [ Links ]

Ward, T. 2009. Words of life: Scripture as the living and active word of God. Grand Rapids, MI: InterVarsity. [ Links ]

Watson, A. 2009. The digest of Justinian, IV. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. [ Links ]

Winsbury, R. 2009. The Roman book: Books, publishing and performance in classical Rome. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co. [ Links ]

1 David Barr (1986) has done some work on orality in Revelation. This present study will provide more robust support for how the Apocalypse would have been performed by the public reader and received by the original audience.

2 This passage reads as follows: "Let anyone who has an ear listen: If you are to be taken captive, into captivity you go; if you kill with the sword, with the sword you must be killed. Here is a call for the endurance and faith of the saints." All biblical quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version unless otherwise noted.

3 Other oracles in the New Testament could be similarly investigated. However, Revelation lends itself to this type of examination because the book is not only apocalyptic in nature, but it is also prophetic. It is prophetic both by forthtelling (e.g. Rev 1:8) and foretelling (cf. Rev 1:19).

4 In contrast to the pressures facing Christians, Judaism, under Roman rule, enjoyed the privilege of the right to practice religion unhindered (Kraybill 1996:172-173). Josephus cites a long list of privileges extended to Diaspora Jews (Ant. 16.6.2). Ephesus, Pergamum, Sardis, and Laodicea all had Jewish communities. It is possible there was little or no persecution during Domitian's reign, assuming a late date for Revelation's composition (Collins 1984:70).

5 The phrase δώ χόν λόγον χοϋ θεοϋ καί την μαρχυρίαν Ίησοϋ (Rev 1:9) may indicate that John was on Patmos for missionary purposes or it could mean that he was sent there as an exile. It is likely that his presence on the island was not for the purpose of proclaiming the word of God, but rather that he had been exiled there by the state as punishment for preaching. The phrase "because of (δώ) is always used in Revelation for the result of an action and not to designate a purpose for an action (Boring 1989:82).

6 The number seven may be symbolic. If so, the seven historical churches are viewed as representative of all the churches in Asia Minor and probably, by extension, the church universal. See Gregory Beale (1999:186-187) for further discussion.

7 No conclusive consensus has been reached on the identity of the angels of the churches to which each of the seven letters in Rev 2-3 are addressed (2:1, 8, 12, 18; 3:1, 7, 14). See Everett Ferguson (2011) for a list of proposals. Ferguson contends that the designation άγγελος refers to the human congregational reader of each church.

8 As noted by Rex Winsbury (2009:112).

9 See also Seneca, Ep. 40.1; Cicero, Att. 9.10.1; Quint. fratr. 1.1.45; Pliny, Ep. 6.

10 See also Select Papyri (1932:112).

11 "Aural" means of or relating to the ear or to the sense of hearing.

12 This was true of other New Testament epistles as well (cf. 1 Cor 5:1 -5).

13 The identity of the "one who is speaking" is somewhat ambiguous and is disputed. However, Jonathan Griffiths (2014:147) contends that in its immediate context, God must have been the ultimate speaker.

14 Of course, the Spirit is also ministering through all these voices, making the message efficacious to the congregations (Matt 10:20; John 16:13; 1 Thess 1:5; Rev 2:7, 11, 17, 29; 3:6, 13, 22).

15 Contra Thomas Martin (2018:249) who says that "ventriloquism does not carry quite the same authority as God's direct voice".

16 See also Matthew 10:40 and John 13:20.

17 Despite John's claim to possess prophetic status (Rev 1: 1-3), there was no guarantee that his message would be accepted by everyone as coming from God. He could have been rejected as other prophets who claimed divine authorisation (cf. Hos 9:7; Mark 6:1-4; Luke 13:31-35; 2 Cor 13:2-3).

18 William Doan and Terry Giles (2005:29) make a similar claim regarding the Old Testament scribe.

19 Daniel Vanderveken (1990:166-219) lists over 270 English performative verbs.