Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

R&D Journal

On-line version ISSN 2309-8988Print version ISSN 0257-9669

R&D j. (Matieland, Online) vol.26 Stellenbosch, Cape Town 2010

A Review of the Machinability of Titanium Alloys

G.A. OosthuizenI; G. AkdoganII; D. DimitrovIII; N.F. TreurnichtIV

IDepartment of Industrial Engineering, Stellenbosch University. E-mail: tiaan@sun.ac.za

IIDepartment of Process Engineering, Stellenbosch University. E-mail: gakdogan@sun.ac.za

IIIDepartment of Industrial Engineering, Stellenbosch University. E-mail: dimitrov@sun.ac.za

IVDepartment of Industrial Engineering, Stellenbosch University. E-mail: nicotr@sun.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Titanium alloys find wide application in many industries, due to their unrivalled and unique combination of high strength-to-weight ratio and high resistance to corrosion. The machinability of titanium alloys is impaired by their high temperature chemical reactivity, low thermal conductivity and low modulus of elasticity. In this paper, the machining fundamentals specific to titanium alloys are presented and the machining of Ti6A14V with conventional and advanced cutting tool materials is reviewed. The experimental results from several sources are discussed and form the basis of a collaborative research project between academia and industry. The selected aerospace benchmark component is presented and milling strategies for machining performance enhancement are discussed.

Additional Keywords: Ti6A14V, manufacturing

Nomenclature

a depth of cut [mm]

f feed [mm]

h chip load [mm]

R surface roughness [μm]

T temperature [°C]

V speed [m/min]

Greek Symbols

α phase, hexagonal close packed crystal structure

β phase, body centred cubic crystal structure

λ thermal conductivity [W/m.K]

ρdensity [g/cm]

Subscripts

a average

C cutting

e radial

x maximum

n revolution

p axial

v tool face

z tooth

1. Introduction

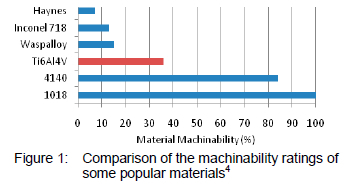

Titanium alloys are used in the aerospace and biomedical industries due to their exceptional strength to weight ratio and superior corrosion resistance1. The amount of titanium in the structure of an aircraft will increase from approximately 7%2 to 15% of the structural weight in the next generation of aircraft such as Hoeing 787 or Airbus 350 XWB3 for a competitive advantage. Therefore, a growing market niche for high value titanium machined components is perceived. Machining is a major cost contributor, but at the same time a differentiating factor. The main focus in process development during the last few years in the aerospace industry has been high performance machining of aluminium alloys. This results in a significant gap between the material removal rates of aluminium and titanium alloys2. Figure 1 illustrates Ti6A14V's machinability by comparing it to the machinability ratings4 of other materials, with 1018 steel as benchmark. Many of the same qualities that enhance titanium's appeal for most applications, also contribute to its being one of the most difficult to machine materiais5.

Titanium alloys are subdivided into α alloys, β alloys and α/β alloys. These alloys form part of the light metals group, due their low density of ρ = 4.5 g/cm3. These alloys also show a high hot strength and can therefore be used at elevated temperatures6 up to 600 °C, which is much higher than the 350 °C considered as the operating temperature7 of compressor blades. Titanium alloys are characterised by a low thermal conductivity of λ = 7 W/m.K, combined with a melting point (1650 "(71930 K) which concentrates high cutting temperatures7. Ti6A14V is the most popular for low thermal stress8,9 aircraft parts and belongs to the α/β alloys. This alloy comprises about 45-60 % of the total titanium products in practical use1,10 and is formed by a blend of alpha and beta favouring alloying elements. The α alloy (hexagonal close packed) is hard and brittle with strong hardening tendency. 'The β alloy (body centred cubic) is ductile, easily formed with strong tendency to adhere7. This alloy can be produced in a variety of formulations, depending on the application. The aluminium content may reach up to 6.75 % (by weight) and vanadium 4.5 %. The oxygen10 content may vary from 0.08 % to more than 0.2% and the nitrogen may be adjusted up to 0.5 %. Raising the content of these elements, especially oxygen11 and nitrogen, will help to increase the strength. Equally, the lower additions of oxygen, nitrogen and aluminium will improve ductility, stress corrosion resistance, fracture toughness and resistance against crack growth11. In order to cope with the challenge of large scale structural parts and the rising number of smaller parts, an understanding of the machining demands of titanium alloys is needed. This paper examines the current state of research in turning and milling; and compares the latest tool materials for the machining of Ti6A14V. Innovative lubrication strategies, tool coatings and tool geometries are evaluated for future development. It also shows a benchmark component from a collaborative research study and a tool wear characterization map from which remedial actions and original strategies are developed to efficiently mill Ti6A14V.

2. Machining Challenges

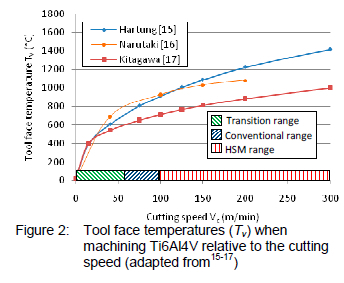

The recommended cutting speeds (Vc) for titanium alloys of over 30 m/min with high speed steel (HSS) tools, and over 60 m/min with cemented tungsten carbide (WC) tools, result in rather low productivity8. The machining challenges can be divided into thermal and mechanical tool demands. The tool face temperature (Tv) is a function of the cutting speed (Vc) and exposure time to this thermal load. The longer the duration of exposure time, the larger the volume of the tool edge, that is exposed to the critical tool temperature12. The combination of titanium's low thermal conductivity and the fact that approximately 80% of heal generated13 is retained in the tool; result in a concentration of heat in the cutting zone (thermal stress). These issues cause complex tool wear mechanisms such as adhesion and diffusion14,15. Figure 2 illustrates the results from studies of the tool face temperature (Tv) when machining Ti6A14V relative to cutting speed (Vc). Similarly, other researchers16,17 also measured temperatures of 900 °C at a cutting speed of 75 m/min.

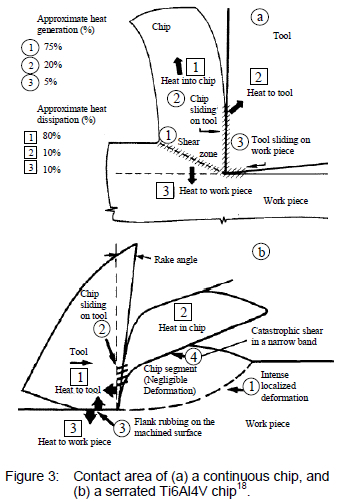

The mechanical demands arc a combination of the work piece chip load on the cutting edge and machining vibrations. Ti6A14V exhibits segmented chip format ion and has been cited to cause much confusion in interpreting cutting data12 in the pre 1980 era. Figure 3 illustrates a general continuous and serrated Ti6A14V chip. The contact area of a serrated chip is found to be only a third10 of the contact area of a continuous chip.

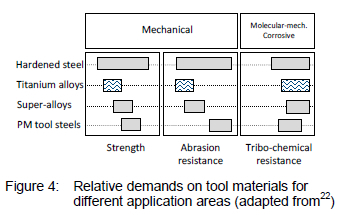

This results in high pressure loads on the cutting edge. Catastrophic tool failure, due to vibration while in cut, is caused by self excited chatter19 and forced vibrations due to the formation of shear localization18 and the fluctuating friction force between the tool and chip flow. According to Shivpuri et al.20 the chip segmentation phenomena significantly limits the material removal rates and causes cyclic variation of force. The combination of a low Young's modulus (114 GPa)21, coupled with a high yield stress ratio allows only small plastic deformations6 and encourages chatter and work piece movement away from the tool. Figure 4 illustrates the demands on the cutting tool material for different application areas in terms of strength, abrasion resistance and tribo chemical wear resistance.

Ti6A14V is associated with very much the same demands as Inconel718, although Inconel718 generates higher cutting forces23 and is more abrasive4. The most challenging demands for a tool material to machine titanium alloys are the tribo-chemical and impact related wear mechanisms. Tribo-chemical wear is a combination of molecular mechanical wear and corrosive wear and may be considered a thermally activated process whereby the work piece material and tool malerial react in such a manner as to remove material from the tool on an atomic scale22. Titanium's chemical reactivity becomes problematic at temperatures above 500 °C. Apart from diffusion wear, it has a strong affinity to adhere which leads to chip adhesion (also known as galling) onto the tool cutting surface. Once a built up edge develops, tool failure follows rapidly24. The unexpected reaction of titanium chips with atmospheric oxygen causing a fire hazard is also a major concern in a workshop.

3. Current State of Research in Turning of Titanium Alloys

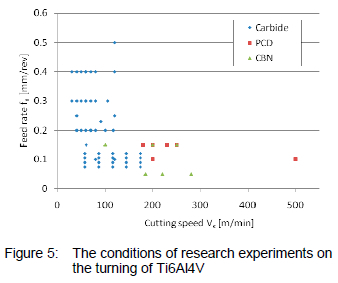

Although the different mechanical loadings for turning are not as severe as in interrupted cutting (milling), research22 indícates that the temperatures generated are significantly higher for mining under nominally the same conditions. As illustrated in figure 516,25,26 carbide tool materials were used for roughing experiments (conventional speeds, high feeds), while polycrystalline diamond (PCD) and Cubic Boron Nitride (CBN) tool materials were used for finishing experiments (high speeds, small feeds). The low experimental conditions clearly exemplify Ti6A14V's machining challenges.

Although experiments wit h carbide are conducted al higher cutting speeds, advisable industry norms for first stage (roughing) turning is still limited to cutting speeds of 30-50 m/min and feeds of 0.3-0.4 mm per rotation27. Finish turning operations are done at cutting speeds ranging from 80-120 m/min and feeds of 0.1-0.2 mm per rotation. From this figure it is evident that high speed machining is still a new titanium machining strategy and that not many experiments have been conducted with PCD and CBN tools. The performance of conventional tool materials are poor when machining Ti6A14V at elevated speeds and the development of cutting tool materials such as CBN and PCD may hold the answer to higher cutting speeds.

4. Current State of Research in Milling of Titanium Alloys

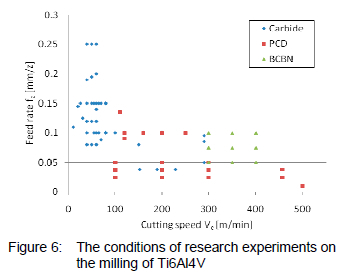

The key demand that distinguishes milling from turning is the interrupted cutting and the related mechanical and thermal shock loading. In milling the tool is subjected to cyclic heating and cooling, causing thermal shock. When the rate of cooling is increased significantly, the result is tool crack formation causing premature tool failure28. Su et al.29 connect cyclic thermal shock directly with thermal crack initiation. It logically follows that an indiscriminate increase of cooling power will yield diminishing returns. Tool wear in milling of TiGAI4V may be modelled as a thermo mechanical high cycle fatigue phenomenon in which the first order effects can be divided into work piece related and catastrophic tool failures22. Figure 6 illustrates the different cutting conditions of research experiments7,12,29-33 on the milling of Ti6A14V. Similar to turning, carbides are used for roughing (conventional speed, high feed) while experiments with PCD and binderless cubic boron nitride (BCBN) show promising results for high speed finishing operations. As indicated in the figure, the rough milling34 of titanium alloys is also defined by conventional cutting speeds (around Vc =50 m/min), but a lower feed per tooth limit (fz = 0.25 mm/z) is evident compared to that for turning (fa =0.5 mm/rev). This clearly demonstrates the higher mechanical and thermal shock loading found in milling operations. Rough milling operations are still limited to cutting speeds of 30-60 m/min35,36 with feed rates of 0.1 - 0.25 mm/z35,36.

High speed milling refers to cutting speeds which are five to ten times higher than conventional speeds37. Finish milling of Ti6A14V shows promising results at cutting speeds in the range of 175-200 m/min12,16, with a feed per tooth or 0.025-0.05 mm/z16,32. The axial depth12 of cut is low (ap =0.5 mm) and the radial immersion38 ranges from ae. = 0.5-2 mm. As the depths of cut are typically shallow in high speed machining (HSM), the radial forces on the tool and spindle are low. Deep immersion can result in severe chatter vibration39 and a low immersion saves spindle bearings, guide ways and ball screws. Although experiments7,33,40 with CBN, PCD and BCBN milling this alloy show promising results, more experimental research and cost studies are needed.

5. Evaluation of Cutting Materials for Titanium Alloys

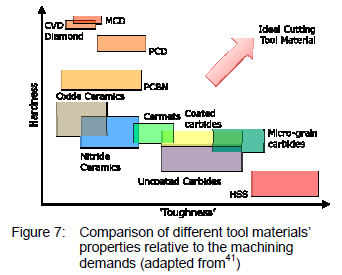

The term toughness should be interpreted not necessarily as the engineering quantity, fracture toughness, but more so as the resistance to chipping or catastrophic failure22. Figure 7 shows that there are always trade-offs between higher cutting speeds and higher feed rates. The tougher high speed steel (HSS) and Micro-grain cemented carbide are predominately limited by their hot hardness (property to withstand the thermal load), whereas PCD, being deformation resistant at higher temperatures, is primarily limited by its toughness (property to withstand mechanical loading).

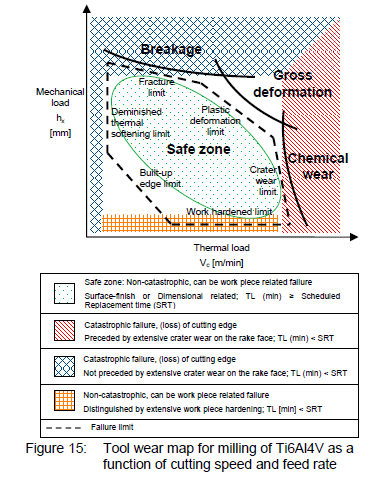

Tool failure can be initiated by one or a combination of several forms of wear, which in an advanced stage may lead to overload or fatigue and catastrophic tool failure22. Note that flank and crater wear are gradual and more predictable than fracture, which occurs suddenly. The key to designing high performance cutting tools is to identify the most economical scheduled replacement time (SRT) used in the industry for the specific component. Thus the tool suppliers can optimize the operational conditions, whereby the cutting tool will withstand the demands of the machining process for a longer period of lime than the SRT. These optimum operational conditions are defined as the safe zone12,41. The following section examines the performance of different tool materials for machining Ti6A14V.

5.1 Machining with carbide tool materials

Straight tungsten carbide (WC-Co) tools are reported43 to have superiority in performance in the nulling of titanium alloys. In another study44 with carbide on the dry end milling of a titanium alloy, the following optimum cutting conditions were obtained, Vc 88 m/min (fz = 0.20 mm/z), Vc = 113.5 m/min 0.15 mm/z) and Vc 163 m/min (fz= 0.10 mm/z), as the best compromise among cutting speed, material removal rate (MRR) and tool life (TL). Uncoated carbide (WC) inserts were used for orthogonal continuous and interrupted cutting at conventional cutting speeds. They8 studied the cutting performance under dry cutting, minimal quality lubrication (MQL.) and flood coolant. According to the authors, MQL was an effective alternative approach to flood coolant during high speed turning of Ti6A14V. Bryant27 confirmed that Vc= 45 m/min is the usual cutting speed for machining titanium with uncoated straight grade cemented carbide (WC-Co) tools. As illustrated in figure 2 this cutting speed will generale tool face temperatures of more than 500 °C and according to research45 titanium alloys are very reactive with carbide cutting tool materials at these temperatures. As a result micro abrasion and attrition are the main causes of carbide tool wear10, due to the adhesion and diffusion of the work piece material.

5.2 Machining with CBN tool materials

Zoya and Krishnamurthy46 studied CBN tools under finishing conditions (fz = 0.05 mm/z and ap = 0.5 mm) at cutting speeds up to 350 m/min. They evaluated the performance of these tool materials with Ti6A14V. It was concluded that it is a thermally dominant cutting process and a critical tribo chemical wear temperature of 700 °C can be a decisive factor for tool life. It was also mentioned that the prominent wear mechanism of CBN tools is diffusion. In another study23 the cutting performance of different CBN tool grades were evaluated for high speed finishing operations of Ti6A14V, with various coolant supplies. The type of tool wear, failure modes and cutting forces were studied, The experimental results revealed that different grades of CBN tools gave lower performance, in terms of tool life, compared to uncoated carbide tools. In addition to this, despite the relatively good cutting performance of CBN, carbide tools are still generally preferred for high speed finishing operations, because of their lower cost6. In a study with pofycrystalline CBN (PCBN) cutting material, it was mentioned40 that higher cutting speeds lead to decreasing cutting forces. This is due to the cutting tool material that is able to keep its strength at elevated temperatures, whereas the work piece material softens at the cutting edge. Complementary to this, research33 with binderless CBN (BCBN) indicated that longer tool life could be achieved in high speed finishing operations, compared to conventional PCBN (85 95 % CBN). BCBN is distinguished by its high thermal conductivity, hot strength and thermal shock resistance. This innovative cutting material is regarded as one of the most important novel materials for HSM of titanium alloys.

5.3 Machining with PCD tool materials

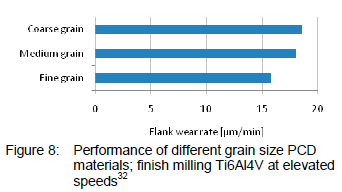

Research studies with PCD tools indicated that it could be a substitute tool material for finish turning operations. Supplementary work18 indicated that PCD produced a better work niece surface integrity. In another Ti6A14V turning study40 the results revealed that PCD (CTB010) could achieve a 3 fold increase in tool life over tungsten carbide at a speed of 200 m/min (fz = 0.05 mm/rev). Similarly, results30 from a TA48 titanium alloy turning study with similar PCD tools, demonstrated a 4 fold increase in tool life over KC850 carbide at a cutting speed (Vc) of 75 m/min (fz = 0.25 mm/rev). Narutaki and Murakoshi16 showed that natural diamond tools used dry at Vc = 100 m/min lasted longer than carbide tools used with a cutting fluid at the same speed. When used with a cutting fluid at Vc = 200 m/min, the diamond tool had the same wear rate as during dry machining at Vc 100 m/min. This, in a way, corresponds with the findings48 on the machining of y-TiAl inter metallic alloys. Their study showed that with a low pressure fluid supply, 2 pm and 10 pm grain size PCD produced similar tool life to that of using WC with a high pressure fluid supply. Regardless of all these positive findings in turning, very little data exists on finish milling of titanium alloys and even less, if any at all, on the rough milling of Ti6A14V using PCD. Polycryslalline diamond exhibits high thermal conductivity and hot hardness, which can be ideal for finish milling Ti6A14V. The lower transverse rupture strength (TUS) can be tolerated, if the correct milling strategy is applied. Finish milling experiments12 reported a tool life of 215 min (Vc = 457 m/min), concluding that high speed milling of TiGAlV4 is possible with PCD. In addition to this, Kuljanic et al.7 also reported a very long tool life (TL = 381 min) with good surface finish and geometrical accuracy in a finish milling operation. The main type of tool wear was found to be diffusion and adhesion. Nurul Amin et al.30 studied the effectiveness of polycrystalline diamond tool materials and compared them to uncoated tungsten carbide cobalt materials milling this alloy. They compared the tools with respect to the applicable cutting speed ranges: metal removal per unit tool life (IvlR/TI.) and tool wear rates, tool wear morphology, surface finish, chip segmentation and chatter phenomena. The authors concluded that PCD inserts can be used effectively up to cutting speeds of 160 m/min, as the wear rate is quite low and the amount of metal removal per tool life unit is considered reasonable. Figure 8 summarizes the performance of the PCD tool materials, which illustrates the effect of tool properties, considering the various cutting conditions. The fine grain material has the highest TRS and coarse material the lowest value. Although the figure indicates that the fine grain material performed best overall, it was interesting to observe that there is a direct relationship between the performance and the transverse rupture strength of the materials.

Similarly, there is an inverse relationship between the grain size (increase in TRS), and wear performance. Research studies51 indicated that the performance of fine grain PCD in experiments is a manifestation of the phenomenon envisaged by Barrien Ritcey12, namely that a tool material with sufficiently high temperature performance will be able to yield better machining productivity through the utilization of the thermal softening of Ti6A14V by means of an α-β phase change.

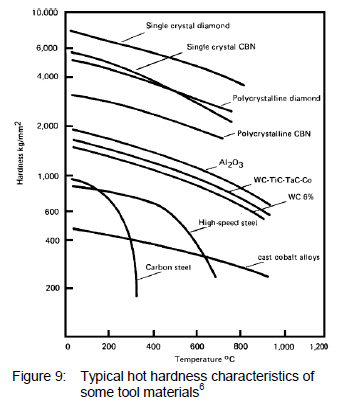

5.4 Summary of cutting tool materials

Advances in cutting tool materials have resulted in an increase in material removal rate (MRR) when cutting titanium alloys. Cutting materials will always encounter extreme thermal and mechanical stresses close to the cutting edge during machining, due to the poor machinability of titanium alloys4. Therefore, the tool material's hot hardness6 is a major requirement for Ti6A14V machining tools. The softening temperatures of commercially available cutting materials are given in figure 8. Most tools lose their hardness at elevated temperatures, caused by the weakening of the inter particle bond strength and the consequent acceleration of the tribo chemical tool wear.

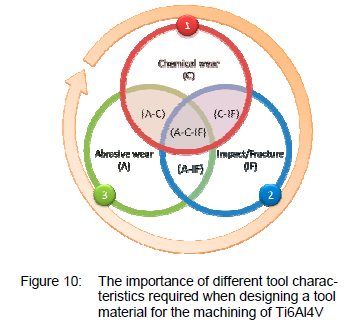

Strength is the property that resists the breakdown of the cutting edge (impact wear) when the mechanical load exceeds the physical properties of the tool material. Abrasion wear is caused by the action of the sliding chips in the shear zone, as well as by friction generated between the tool flank and work piece. Abrasion wear happens primarily due to the hard grain orientations in the titanium alloy, which can act like hard inclusions in the work material and is compounded by the part's hardness and strength properties. Figure 10 illustrates the importance of different tool characteristics that are required from innovative tool materials to efficiently machine Ti6A14V.

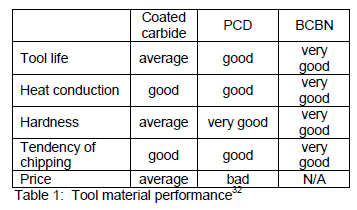

As illustrated in figure 10, the chemical wear resistance of the tool material is the first priority, followed by impact and abrasive wear resistance. Table 1 summaries the perform anee of different cutting materials used to titanium alloys. As indicated in the table, although PCD materials perform well, it is still a very expensive cutting material that needs further development.

Although BCBN is the best cutting material for titanium alloys under high speed conditions according to literature33, it is still not commercially accessible and the price is not available. Coated carbide and HSS are cost effective, and still the most commonly used cutting materials for titanium alloys in the industry.

6. Lubrication Strategies

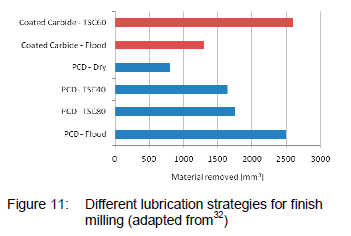

Lubrication and cooling strategies for titanium machining operations are areas where the cutting process can be improved. During interrupted cutting the tool is subjected to cyclic heating and cooling that can cause thermal shock12. When the rate of cooling is increased significantly, the result can be thermal shock, causing catastrophic tool failure, if the thermal load (at elevated cutting speed) is too high for the tool material . Su et al.29 connect cyclic thermal shock directly with thermal crack initiation. The low thermal conductivity of Ti6A14V causes a concentration of the heat build up in the cutting zone'. When the cutting zone is shielded from the lubricant stream such as in cutting with deep axial immersion, the coolant needs to be focused on the cutting edge52. At high tool temperatures, typically above 550 °C, the heat transfer mechanism between the cooling fluid and the tool surface changes to two phase high speed flow12. The coolant is vaporized on contact with the heated tool surface, forming an insulating boundary layer on the tool surface. The phenomenon is also described as delayed surface wetting in heal transfer literature12. The performance of the different lubrication strategies for finish milling with PCD is illustrated in Figure 11. Coaled carbide tool materials with flood lubrication were used as benchmark.

Flood lubrication had the lowest flank wear rate, resulting in the longest tool life. This proves that PCD is not as susceptible to thermal shock as found with carbide29. The 80 bar TSL. performed better than the 40 bar TSL. and dry machining had an accelerated wear pattern. The lubrication pressure employed with the 40 bar and 80 bar TSL strategies enabled the insert to reach more than twice the tool life compared to dry machining, while flood lubrication reached more than three times the tool life of dry machining. Liquid Nitrogen cryogenic cooling53 and minimum quantity lubrication (MQL)54 also show promising results and should be considered in future research studies.

7. Performance Enhancement of Milling Strategies

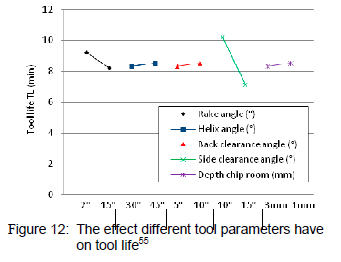

Titanium alloys are used for high value components, not only components used in an aircraft's frame and engine, but also in the biomedical field. Workshops able of sustained growth will migrate toward higher end work, meaning that a gtowing percentage of machining shops will encounter titanium alloys. Therefore attention to milling titanium is worth while in order to achieve higher productivity, when raising the cutting speed is not an option. Results55 from research collaboration study details the effect of tool geometry on tool life. As illustrated in figure 12, the side clearance angle of the tool is the most influential.

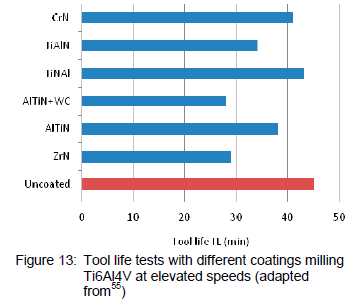

Another solution to protect tool materials from thermal load is the use of a coating. The perfect coating should have a high temperature resistance, a high toughness and limited thickness in the sub 10 micron range. Figure 13 shows results of different experimental coatings milling Ti6A14V. None of these coatings improved tool life relative to the uncoated tool. It should however be noted that coatings like TiSiN were not tested in this study".

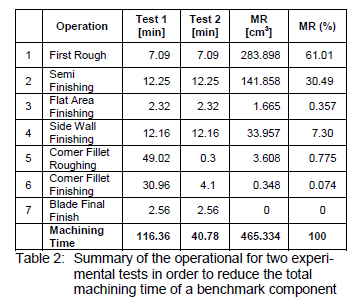

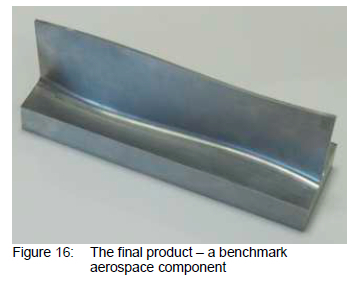

An explanation might be that the coated surface is rougher, which leads to the slicking of the chips to the rake of the tool56. The cutting edge of the tool is also not as necessarily sharp as an uncoated tool and dining preparation phase (before applying the coating) the tool material can become brittle55. Based on this study, it can be concluded that none of the experimental coatings are suited for HSM of Ti6A14V. In a collaborative research study57 between the academia and aerospace industry a benchmark part was used to understand the tool demands from the Ti6A14V work piece and to improve the milling strategies used currently in industry. Table 2 illustrates the different operations to machine this component. The material removed (MR) per operation is indicated. Test 1 and test 2 are the result of various simulations and background experimental studies. Cutting tool materials and parameters were varied to improve the machining time for the benchmark component.

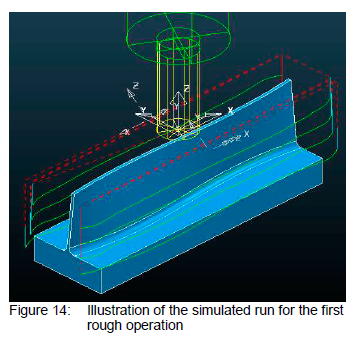

The revision of the machining strategies with new generation cutting tools showed a significant reduction from 116 to 41 minutes in the total machining time. An aluminium version of the same benchmark component required nominally 14 minutes to machine. Compared to the 41 minutes to machine a Ti6A14V part, it is evident why titanium machining needs further experimentation. Figure 14 illustrates the first roughing operation of this component.

High depths of cut (ap) were possible with a large radial immersion (ae). Using the wear characterization map illustrated in Figure 15, which is developed specifically for the milling of Ti6A14V alloys, improved parameters and milling strategies were realised for the cutting of the corner fillet of the component. The used tools were examined with an optical microscope and scanning electron microscope (SEM) imaging and were characterized so as to categorize ι hem into a failure region. Thus, remedial actions could be considered to improve the process. Both the roughing and ι he semi finishing for this benchmark component can now be completed in less than 20 minutes.

Tool failure during the roughing operation took place after approximately 35 minutes of cutting time (or after 1½ components). Similarly it is calculated that the tool life in the aerospace industry should exceed 30 minutes to ensure an economical viable solution55, as most scheduled tool replacement limes (SRT) are less than this. Figure 16 illustrates the final Ti6A14V product.

The titanium pari had a good surface roughness value (Ra = 1.01 μm) and the component's accuracy was acceptable. Through an iterative approach a significant reduction in machining lime was achieved, proving that the correct milling strategies are of critical importance.

8. Conclusions

The key tool demands for efficient machining of Ti6A14V were identified. The current stale of research in turning and milling was examined and the latest tool materials for the machining of Ti6A14V were compared. The present most efficient operating parameters for rough turning and milling, and for finish turning and milling were identified. The current slow cutting speed implies that roughing and finishing are still required to achieve productive material removal for titanium alloys. Innovative lubrication strategies, tool coalings and tool geometries for the machining of a benchmark Ti6A14V component were evaluated for future development. A tool wear characterization map was illustrated and was used to identify the optimum cutting parameters. The preferred scheduled tool replacement time (SRT) for aerospace components was confirmed to be in the order of 30 minutes.

9. Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the Advanced Manufacturing Technology Strategy (AMTS) programme, an initiative of the South African Department of Science and Technology (DST). The authors also gratefully acknowledge the material and financial support provided by element Six Pty (Ltd).

References

1. Mantle A and Aspinwall D, Tool life and surface roughness when high speed machining a gamma titanium aluminide, progress of cutting and grinding, fourth International Conferenee on Progress of Cutting and Grinding, Urumqi and Turpan, China, International Academic Publishers, 1998, 89 94.

2. Lange M, Hochleislungsfräsen von Titanbauleilen fur den Flugzeugbau, Proceedings of Neue Fertigungstechnologien in der Luft und Raumfahrt; Hannover, Germany, 2007, 28-29.

3. Denkena B and De Leon LKJ, Performance enhancement in milling titanium, Proceedings of the 3rd International CIRP High Performance Cutting Conference, University College, Dublin, Ireland, 2008. 743-751.

4. Grzesik W, Advanced Machining Processes of Metallic Materials: Theory, Modeling and Applications, Grezsik W, editor: Klsevier; 2008.

5. Byrne G, Dornfeld D and Denkena B, Advancing cutting technology. Keynote papers STC "C", Annals of CIRP, 52(2), 2003, 483-508. [ Links ]

6. Ezugwu E, Bouncy J and Yamane Y, An overview of the machinability of aeroengine alloys, Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 2003, 134, 233-253. [ Links ]

7. Kuljanic E, Pioretti M, Beltrame L and Miani F, Milling titanium compressor blades with PCD cutter, Annals of the CIRP, 47(1), 1998, 61-64. [ Links ]

8. Lopez de Lacalle L, Perez J, Llorenle J, and Sanchez J, Advanced cutting conditions for milling aeronautical alloys, Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 2000, 100, 1-11. [ Links ]

9. Eckstein M, Lebküchner G and Blum D, Schaftfräsen von Titanlegierungen mit hohen Schnittgeschwindigkeiten, Teil 1: Schruppen, VDI-Z, 1991, 133(12), 28-34.

10. Luthering G and Williams J, Titanium New York: Springer Verlag, 2003. [ Links ]

11. Donarchie MJ, Titanium, A Technical Guide: ASM Iniernational, 2000.

12. Barnett-Ritcey D, High Speed Milling of Titanium and Gamma Titanium Aluminide: An Experimental Investigation. PhD dissertation, McMaster University, McMaster, Canada, 2004. [ Links ]

13. Bhaumik S. Divakar C and Singh A, Machining Ti-6Al-4V alloy with a wBN cBN composite tool, Materials and Design, 16(4), 1995, 221 226. [ Links ]

14. Corduan N. Himbert T, Poulachon C, Dessoly M, Lambertin M and Vigneau J, Wear mechanisms of new tool materials for Ti-6A1-4V high performance machining, Annals of the CIRP, 52(1), 2003, 73-76. [ Links ]

15. Hartung PD. Kramer BM, Tool wear in titanium machining, Annals of the CIRP, 31(1),1982,75-80. [ Links ]

16. Narutaki N, Murakoshi A, Study on machining of titanium alloys, Annals of CIRP, 32(1), 1983,65-69. [ Links ]

17. Kitagawa T, Kubo A and Maekawa K, Temperature and wear of cutting tools in high speed machining of inconel 718 and Ti6A16V 2Sn, Wear, 1997, 202(2), 142-148. [ Links ]

18. Komanduri R and Hou ZB, On thermoplastic shear instability in the machining of a titanium alloy (Ti6A14V), Metallurgical and Materials Transactions, 33(9), 2002, 2995-2301. [ Links ]

19. Altintas Y, Week M, Chatter, Stability of metal cutting and grinding, Annals of CIRP, 53(2), 2004, 619-642. [ Links ]

20. Shivpuri R. Hua J. Mittal P and Srivastava A. Microstructure-mechanics interactions in modeling chip segmentation during titanium machining, Annals of the CIRP, 2002, 51(1),71-74. [ Links ]

21. Kuljanic E, Fioretti M, Beltrame L and Miani F, Milling titanium compressor blades with PCD cutter, Annals of CIRP, 1998, 47(1), 61-64. [ Links ]

22. Barry J, Akdogan G. Smyth P. McAvinue E, and O'Halloran P, Application areas for PCBN materials. Industrial Diamond Review, 66(3), 2006, 46-53. [ Links ]

23. Pang N and Wu Q, A comparative study of the cutting forces in high speed machining of Ti-6A1-4V and Inconel 718 with round cutting edge tool, Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 209, 2009,4385-4389. [ Links ]

24. Kirk D, Cutting Aerospace Materials (Nickel, Cobalt, and Titanium-Based Alloys), 1971.

25. Ezugwu E, Bonney J, Da Silva Rosemar B. and Cakir O, Surface integrity of finished turned Ti 6A1-4V alloy with PCD tools using conventional and high pressure coolant supplies, International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture, 47, 2007, 884-891. [ Links ]

26. Jaffery S and Mativenga P, Assessment of the machinability of Ti-6A1-4V alloy, International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 40, 2009, 687-696. [ Links ]

27. Che-Haron C and Jawald A, The effect of machining on surface integrity of titanium alloy Ti-6% A1-4 %V. Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 166, 2005,188-192. [ Links ]

28. Wang Z. Sahay C and Rajurkar K, Tool temperatures and crack development in milling cutters, International Journal of Machine Tool and Manufacture, 36(1), 1996,129-140. [ Links ]

29. Su Y, He N, Li L and Li X. An experimental investigation of effects of Cooling/Lubrication conditions on tool wear in high-speed end milling of Ti-6A1-4V, Wear, 261(7-8), 2006, 760-766. [ Links ]

30. Nurul Amin A, Ismail A and Nor Khairusshima M, Effectiveness of uncoated WC-Co and PCD inserts end milling of titanium alloy Ti6Al 4V, Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 192 193, 2007, 147-158. [ Links ]

31. Elmagrabi N, Che Hassan C, Jaharah A and Shuaeih F, High speed milling of Ti-6A1-4V using coated carbide tools, European Journal of Scientific Research, 22(2), 2008, 153-162. [ Links ]

32. Oosthuizen G. Joubert H, Treurnicht N, and Akdogan C. High-speed milling of Ti6A14V, In: International Conference on Compel itve Manufacturing, Slellenbosch; 2010.

33. Wang Z. Rahman M. and Wong Y, Tool wear characterizatics of binderless CBN tools used in high speed milling of tilanium alloys, Wear, 2005, 258, 752-758. [ Links ]

34. Konig W, Kloeke F, Ferligungsverfahren. 17lh ed. Berlin, Springer Verlag, 2007.

35. Kitagawa T. Kubo A and Maekawa K, Temperature and wear of cutting tools in high speed machining of Inconel 718 and Ti 6A1 6V 2Sn., 1997, 202, 142 148.

36. Che Haron C, Jawaid A and Sharif S, Evalualion of wear mechanisms of carbide tools in machining of titanium alloy, In: Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference AMPT. Kuala Lumpar, Malaysia, 1998.

37. Schulz H and Moriwaki T, High Speed Machining, Annals of the CIRP, 1992,41(2),637-643. [ Links ]

38. Sage C, Wirtschaftliches Frasen von Titanlegierungen mit Hochgeschwindigkeit oder konventionellen Verfahren, 1998.

39. Buelak E, Improving productivity and part quality in milling of titanium based impellers by chatter suppression and force control. Annals of CIRP, 49(1), 2000. [ Links ]

40. Ezugwu E, Wang Z, Titanium alloys and their machinability a review, Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 1997, 68, 262 274. [ Links ]

41. Quinto D, Technology perspective on CVD and PVD coated metal-cutting tools, International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials, 14, 1996, 7-20. [ Links ]

42. Kendall L, ASM Metals Handbook. 9th ed., 1989.

43. Komanduri R and Reed J, Evaluation of carbide grades and a new cutting geomtry for machining titanium alloys, Wear, 1983, 92, 113-123. [ Links ]

44. Gintin A and Nouari M, Experimental and numerical studies on the performance of alloyed carbide tool in dry milling of aerospace material, international Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture, 2006, 46, 758-768. [ Links ]

45. Bryant W, Cutting tool for machining titanium and titanium alloys, US Patent, Report No. 5718541, 1998.

46. Zoya Z and Krishnamurthy R, The Performance of CBN tools in the machining of titanium alloys, Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 2000, 100, 80-86. [ Links ]

47. Konig W and Nciscs A, Turning Ti6A14V with PCD, Industrial Diamond Review (TDR), 1993, 2, 85-88. [ Links ]

48. Sharman A, Aspinwall DDR and Bowen P, Tool life when turning gamma titanium aluminide using carbide and PCD tools with reduced depths of cut and high pressure fluid, In: Proceedings of 28th NAMRC. 2000, 161-166.

49. Hoffmeister H. Superabrasive machining of Ti6A14V, Industrial Diamond Review (IDR), 2001, 4, 241-246. [ Links ]

50. Nabhani F, Machining of Aerospace Titanium Alloy, Robotics and Computer Intergrated Manufacturing, 2001, 17, 99-106. [ Links ]

51. Oosthuizen G, Innovative Cutting Materials for Finish Shoulder Milling Ti 6A14V Aero engine Alloy, MScEng Thesis, Department of Industrial Engineering, Stellenlosen University, Stellenbosch, 2009. [ Links ]

52. Wang Z. Saliay C and Rajukar K, Tool temperatures and crack development in milling cutters. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture, 36(1), 1996, 129-140. [ Links ]

53. Ahmed MI, Ismail AI, Abala YA, Nuru and Amin AKM, Effectiveness of cryogenic machining with modified tool holder, Jornal of Materials Processing Technology, 2007, 185, 91-96.

54. Brinksmeier E, Walter A, Janssen R and Diersen P, Aspects of cooling lubrication reduction in machining advanced materials, Proceedings of institution of Mechanical Engineers, 1999, 769-778.

55. Ten Haaf P, Mielnik K and Tauwers B, Development of HSC strategies and tool geometries for the efficient machining of Ti6A14V, Proceedings of the 3rd International CIRP High Performance Cutting Conference, University College Dublin (UCD) Relfield Campus, 2008, 753-761.

56. Nouari M, Abdel Aal H and Ginting A, The effect of coaling delaminalion on tool wear when end milling aerospace titanium alloy Ti6242S, 5th International Conference on Metal Cutting and High Speed Machining, 2006, 905-915.

57. Dimitrov D, Hugo P. Saxer M and Tretimicht N, High performance machining of light metals with the emphasis on titanium and selected alloys, Internal Report, AMTS: Slellenbosch, 2010.

Received 26 May 2009

Revised form 7 September 2010

Accepted 31 October 2010