Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning

On-line version ISSN 2310-7103

CRISTAL vol.12 n.2 Cape Town 2024

https://doi.org/10.14426/cristal.v12i2.2207

ARTICLES

Empowering marginalised students in access programmes: A gendered and Afrocentric approach to a decolonised academic literacy curriculum

Linda Sparks

University of the Free State

ABSTRACT

Reading during academic literacy (AL) courses may improve academic skills and empower marginalised students' access to education. However, reading curricula might not address the interests, cultural background, and gender context of South African students. Calls for the decolonisation of the curriculum and gender equality remain largely unaddressed. This research aims to address this gap by assessing whether students experience a decolonised, Afro/gender-centric, intensive reading curriculum as beneficial and empowering. Student interest in reading is crucial for acquiring reading skills and from these, AL skills which are key to student success in a multilingual context. A secondary objective is to explore students' perceptions of reading skills improvement, including reading interest. An interpretivist approach embedded in critical theory was used to guide this research. A mixed-method approach measuring students' perceptions revealed that exposure to decolonised and gender-inclusive texts was empowering and beneficial for academic skills.

Keywords: academic literacy, Afrocentric, decolonisation, gender, reading

Introduction and background

The call for decolonisation of curricula in higher education institutions throughout South Africa and Africa can be heard, and therefore this should also apply to academic literacy modules (Angu, et al., 2020; Dison, 2018; Eybers, 2023; Joubert & Sibanda, 2022; Van Aardt, 2019). Academic literacy is in an ideal position to advocate equality and liberation within the outcomes it proposes for achieving its aims because it is often the intermediary as a support subject to content subjects and inhabits 'both the academic and the support spaces' (Joubert 2024: 2). In addition, Eybers (2023: 49) points out that academic literacies provide 'vital tools that scholars utilise to create, challenge and modify epistemologies in disciplines and academic fields'. Thus, it is important, given South Africa's history of systemic racial oppression to address the need to move away from oppressing epistemologies and rather embrace those that are inclusive and diverse. Therefore, the content within academic literacy modules should explore diverse texts inclusive not only of race but also of gender, and in so doing, providing students with knowledge from their own backgrounds and the ability to generate new knowledge with which to critique systemic injustice (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018; Rasool & Harms-Smith, 2022). This can be achieved through texts which approach content from a decolonised and gender inclusive perspective, and quite simply through 'reading for pleasure' (Morse, et al, 2024: 2; Stoller, et al., 2013: 5). According to Morse, et al. (2024: 2) reading for enjoyment encourages a culture of reading which motivates students and assists them in acquiring the reading proficiency needed for succeeding in the university environment, especially if it occurs regularly. This is reiterated by Adjei-Mensah, et al. (2023: 1) who assert that '[r]eading proficiency is vital to academic success'. Yet, in the English academic literacy classroom, the majority of students may never have encountered a story, poem or book written by their own marginalised peoples, inclusive of both race and gender. This suggests the need to be inclusive of those on the margin within the reading curriculum of this specific academic literacy module which caters for access programme students, and which is compulsory in the first year of study.

Ndimande (2013: 20) confirms that 'curricula remain unrepresentative of black ethnic groups' cultures and epistemologies'. In the under-resourced schools, students originate from, reading focuses on Western literature and therefore authentic South African/African/Black/Female voices are not always heard (Silverthorn, 2009: 61). The over-reliance on imperialistic, Eurocentric, and patriarchal epistemology (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2013: 2) results in the written word remaining foreign to the majority of students because it is difficult for them to relate to the voice of the coloniser and the oppressor (Joubert & Sibanda, 2022: 48). Thus, once students are at university, exposure to the texts of diverse peoples is of importance in being able to move away from Eurocentric reading materials. In addition, students should be encouraged to learn in an environment that supports Afrocentricity as a teaching and learning methodology; for example, if students are allowed to embrace the epistemological values of Ubuntu as this article suggests, a learning environment that supports diversity is encouraging and empowering; (Angu, et al., 2020; Schrieber & Tomm-Bonde, 2015).

One of the main aims of academic literacy is to improve students' reading skills. However, it is a social injustice if prescribed texts are western and patriarchal, and therefore symbolic of the very oppression students are seeking to escape (Knowles, 2019). In other words, attempts should be made where possible by HEIs, including AL modules, to move away from male-dominated and Eurocentric texts and allow students to gain exposure to gender/Afrocentric reading material. Thus, this research aims to address this inequity wherein western/male dominated texts take priority in reading curricula, through a more balanced and inclusive approach by analysing student perceptions of a decolonised, gender inclusive reading curriculum. The research questions which informed this study and from which the aims and objectives above are derived are:

1) Do students find social justice benefits and empowerment from a decolonised Afro/gender-centric reading curriculum?

2) Do students find that this reading curriculum improves reading skills as well as interest and motivation in reading for application in real world contexts?

3) Do students find this curriculum beneficial for not only reading, but for other academic skills such as critical thinking, writing and general knowledge (which further provides empowerment)?

The multilingual students who form the target group of this study and those who are largely affected by the above-mentioned are University Access Programme students on a Higher Certificate at a South African university in the Free State. These students are all enrolled on this Higher Certificate for Humanities and Economic and Management Sciences and are required to complete a compulsory academic literacy course alongside other developmental subjects and major subjects before gaining access into Extended first-year university study. Students on the programme are those who did not meet university requirements and have an admission point of between 18-25 (Marais & Hanekom, 2014: 12; Sekonyela, 2023: 89). In most cases, students fall into a basic to and lower intermediate reading and language level (Van Wyk, 2014: 214), which means that there is a great need to improve motivation and interest in reading (Morse, et al. 2024; Stoller, et al., 2013), thus enabling them to gain much-needed academic literacy skills needed for success at university (Adjei-Mensah, et al., 2023). Therefore, this article has as its focus the assessing of students' perceptions of a decolonised and gender-equal reading curriculum. Of special interest to this, is also whether students were more invested in reading content which aims at being socially just when it comes to race and gender. The following sections will explore why there is a need for such a reading curriculum, especially in terms of decoloniality and gender equality. After this, the way the curriculum was implemented will be addressed, followed by methodology, results, and recommendations.

Exploring the need for gender equality and decolonisation within Academic Literacy

Movements such as #FeesMustFall and #RhodesMustFall in which 'students combined forces, and their voices, to ignite social change' (Joubert & Sibanda, 2022: 51). This clearly shows that South African university students' 'disruption' and epistemic 'disobedience' (Mabasa, 2017) is a plea for change of the systemic and hierarchal order of being, which includes the need to update and make relevant the content of South African curricula. In the midst of this student unrest and protest, which should be interpreted as a struggle to overcome class discrimination, two distinct voices can be heard (Mabasa, 2017). The loudest is undoubtedly race but lately concerns about gender inequality have also come into play, especially as violence against women in all its forms remain inherent in South African society (Knowles, 2019: 117; Mabasa, 2017: 94). Therefore, the need for addressing epistemic injustice within the curricula is of utmost importance and this can have an empowering effect for students engaged in gender/Afrocentric reading, in this case, for access students often originating from marginalised circumstances on this academic literacy module.

Knowles (2019: 119-120) emphasises that 'we fail the public' and the youth, without a 'relevant pedagogy, and a curriculum that [is] responsive to the experiences and challenges of students'; this includes being responsive to racial and gender discrimination. Therefore, of paramount importance is that the 'centrality of the narratives of marginalised groups' is recognised in order to acknowledge and give voice to those oppressed by systems of dominance (Knowles, 2019: 123). Thus, this research seeks to bring together the voices of the oppressed through a reading curriculum in an academic literacy course, which voices similar human elements, whether male, female, white and black, to uphold Martin Luther King's (1973: 3) 'the 'sacredness of human personality'. Similarly, if, as Alice Walker (1983: 7) suggests, a non-separatist, 'universalist' approach inclusive of 'all', then a socially just method towards transformation and equality can be realised for 'all' who seek an end to systemic injustice, 'regardless of race, color, gender, or any ethnical differences' (Ayyildiz & Koçsoy, 2020: 30). This is the approach taken in attempting to 'degender' and decolonise reading in this AL module.

In tertiary institutions today, students are faced with the problem of accessing education, accessing finances for education (Knowles, 2019; Mabasa, 2017; Walker & Mathebula, 2020) and, worse still, accessing the languages and texts of education in a second, but more likely third, or fourth language (Joubert & Sibanda, 2022: 47). In addition, students have been let down by systems of education scarred by the Bantu education laws of Apartheid, which in reality remain neglected into the present moment (Angu, et al. 2019; Eybers, 2023; Ndimande, 2013: 20). In addition, as Ndimande (2013: 20) attests, '[l]arge disparities in resources between black township (still segregated) and formerly white (now desegregated) schools remain'. The primary aim of Bantu curricula was to provide 'cheap sources of labour' for the white minority whilst discouraging African languages, culture, and ways of being and denying students access to education which allowed for critical thinking, and analysis (Angu, et al., 2020: 3). In advocating for a transformation and decolonisation of academic literacy as a subject, Angu, et al. (2020: 3) confirm that,

it is evident the apartheid government applied curricula that uses culture, including language, to reinforce class and power relations. Bantu Education was destructive in its constraining of African communities, and its effects can still be seen in the current era.

The education system today remains oppressive because schools in the quintile 1-3 range, which most students from rural areas originate from, are poorly resourced, providing 'low quality education' (Walker & Mathebula, 2020: 1194). This means that students entering tertiary institutions should be allowed the opportunity to turn this situation around and to empower themselves through resources that are socially just and inclusive of their circumstances. Linked to this is the learning environment which can also follow Afrocentric philosophies like Ubuntu. Thus, while the state of education remains 'destructive' (Angu, et al., 2020), the act of decolonising should be, as Frantz Fanon (1963: 35) argues, a 'violent phenomenon' in transformation. If this violence is not with the physical weapons of the oppressed then it should at least be with the weapons of the oppressed peoples' intellect, knowledge, and way of being (Fanon, 1963). This is true for addressing not only calls for decolonisation but indeed, all forms of discrimination which capitalist, white supremacy (hooks, 2013; Rasool & Harms-Smith, 2022) has dominated for centuries, and of which gender discrimination is one. Therefore, reading that is inclusive of race and gender critiques power structures and assists with empowering students (Angu, et al., 2020).

Adding to these injustices is that this 'second' language of tuition may be seen as the language of the oppressor and coloniser (Angu, et al., 2020; Joubert & Sibanda, 2022). It is no wonder that students lash out. Similarly, the patriarchal nature of these systems remains largely unaddressed (Gouws & Coetzee, 2019; Mabasa, 2017: 106). Recent campaigns like the #EndRapeCulture campaign clearly show this reality, especially in light of the fact that young women so clearly lack the support of their male counterparts (Gouws, 2017: 20). Thus, women's empowerment which continues to remain unaddressed should also be of importance, and together men and women of all races should not only be aware of but should take up arms in 'violence' (Fanon, 1963) to find a truer state of being. As bell hooks (2013: 9) makes clear, the problem is not only racism but 'imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy'. This refers to race and gender, but also all forms of discrimination which so many have suffered as a result of white supremacy (hooks, 2013; Rasool & Harms-Smith, 2022). By bringing this to the forefront of the war against social injustice, especially through exposure to the ways in which white supremacy is rampant and socialised within us, we can challenge the 'hegemonic status quo' (Daniels, 2023: 54).

In this context, the development of academic literacy is 'a criterion for successful achievement at the tertiary level' and should assist students in accessing education without the danger of any pitfalls by addressing the above-named issues of the past and present (McWilliams & Allan, 2014: 14). Furthermore, reading is more than likely the most essential skill for second language learners in an academic setting (Grabe, 1991) and is 'critical for academic success' especially when linked with writing ability (Grabe & Stoller, 2019: 152). It is from reading, that all other academic literacy skills may be acquired, and reading is inextricably linked to these academic literacy skills (Grabe & Zhang, 2016). Clearly then, if reading level can be improved, and academic literacy skills as a result, then students gain a better chance of success at university (Adjei-Mensah, et al., 2023; Grabe & Stoller, 2019). This in itself is also a matter of social justice, because reading empowers students and better still, reading material which is diverse and questions or 'contests' power structures can be of further liberation (Angu, et al., 2020: 6).

In truth, as Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2018) attests "rethinking thinking" by critique of systemic injustices of hegemonic powers provides a means to reestablishing epistemologies. Through reading which approaches texts which are relevant to students' lives and to the social justice issues they experience, they have access to their epistemological knowledge of their own peoples and can also begin to express their voices through generation of their own knowledge (Angu, et al., 2020; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018). This upsets the power structures which have dominated the oppressed. This crucial aspect of gaining a voice by creating knowledge through 'rethinking thinking' and 'unlearning learning' to relearn is based on a 'strong conviction that all human beings are not only born into a knowledge system but are legitimate knowers and producers of legitimate knowledge' (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018: 33). Therefore, through the reading of empowering texts, students may find a form of social justice to not only find their own empowerment, but also to gain access to the structures which have dominated them and thus turn the structure upside down, 'from the bottom up' (Fanon, 1963: 35).

The next sections of this article examine the teaching context which brings the philosophy of Ubuntu into the classroom to further disrupt power structures of the white patriarchal, imperialist brand. This also brings in the importance of analysing texts through scaffolding and intensive reading in the classroom which may assist in breaking down barriers of discrimination and creating an empowering environment where systems of domination can be questioned. After which, research methodology, results and findings will be discussed.

Ubuntu as a 'weapon' in destructing systems of oppression: Teaching and learning context

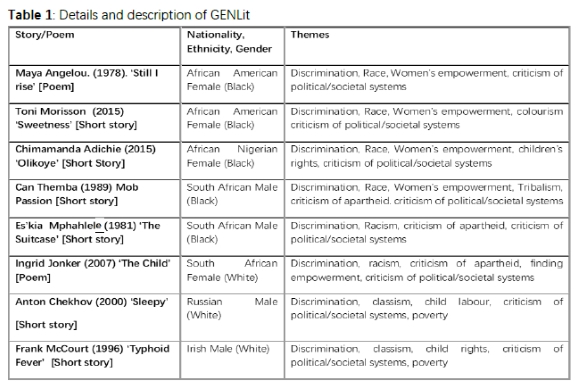

The study's main aim is to investigate students' perceptions of a diverse reading curriculum, hereon referred to as 'GENLit'. The name is derived both from the subject which is a General English Academic Literacy and Language (GENL) module and from the content whose target audience is the 'generation of today' whom Mabasa (2017) refers to as the 'born unfrees'. The focus of this reading content has a common theme of discrimination in general, but also of gender and race. This subject has been in existence since 2016 with the emergence of the Higher Certificate. GENLit became part of a curriculum design initiative which was introduced in 2018 to assist students' reading proficiency, but also with the purpose of providing students with relatable, Afro/gender-centric, decolonised reading material. In addition to this, the African philosophy of Ubuntu that emphasises oneness and working together embraces a teaching pedagogy that breaks away from Eurocentric and individualist teaching styles; this will be discussed in more detail after a brief description of the reading curriculum. Therefore, to answer calls for decolonisation and women's empowerment, a selection of short stories and poems now forms part of the academic literacy module.

In addition to this, the workbook for this subject has been designed by the researcher for South African students and is inexpensive and available in both online and paper formats. This allows for both a blended approach and access to both digital and hard copy in line with previous research which attests to the benefit of both forms of access to the written word in everyday life (Stoller & Grabe, 2019). Assessment also takes a blended approach and enables students to express their voices through various means, including quizzes, reflective activities, videos, presentations, and debate, thus echoing suggestions from previous research for broader, less westernised, relevant, and collective assessment which sometimes follows the oral tradition (Angu, et al., 2020; Eybers, 2023; Mabasa, 2017). The teaching and learning context which follows the philosophy of Ubuntu will be described below, as well as the importance of analysing texts in an intensive, scaffolded teaching approach which assists 'academic literacies development' (Dison, 2018: 72). Firstly though, the stories and poems which make up the GENLit reading curriculum (Table 1 below), as well as how the texts are set up to create an academic platform for students to engage in, will be described.

This reading curriculum follows an intensive reading approach with pre- while- and post-reading sections, which aims to assist students to learn how to process read and thereby improve their skills in accessing a text. Grabe and Stoller (2019: 150) believe that this process approach permits 'students to be exposed to and practice the range of reading sub-skills and strategies used by skilled readers at different points in the reading process'. It also allows for students to engage gradually with texts and to development their metacognitive knowledge and reading strategies in text analysis (Grabe & Stoller, 2019). In this case, the literature first acts as a vehicle for students to be scaffolded into understanding a fictional text through reading strategies and guidance from the educator, and then this same process is used to access an academic text. Scaffolding occurs when learners are given opportunities to engage in the learning process in their Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, 1962). These scaffolds or building blocks along the ladder of learning are removed until the learner has acquired the skill through practice and interaction with peers and educators which develops academic literacy (Dison, 2018) and in this case reading skills (Grabe & Stoller, 2019). Thus, students learn to gradually access and understand both fictional texts which may be of interest to them, and which have themes of social justice, and those which relate to this, but which they are likely to come across in their content modules. This allows for relevance both to culture and to content in other subjects which provides motivation for students for reading application, skills transfer, self-efficacy, and other important academic literacy skills which assist in academic success (Boakye, 2015; Dison, 2019; Grabe & Stoller, 2019; Van Aardt, 2019). The stories and poems consist of both male and female authors of different cultures and nationalities. This can be seen in Table 1 above which also shows the themes addressed in each story or poem.

The reading material consists of mostly black and female authors of the African diaspora. Three white authors (one of whom is female and South African) have been included so that students also have the experience of reading authors who take a critical stance of societal systems of injustice (Angu, et al., 2020), but who are not necessarily of African descent. The aim here is to be inclusive of authors who do advocate for social justice, thus exposing students to a variety of empowering world views. Being exposed to his/'herstories' (Etim, 2020) of those who have been oppressed outside of Africa assists in providing diversity and acknowledgement of world-wide struggles and a greater empathy with humanity. In addition, each author's background and life story are part of the analysis process, thus students gain exposure to real-life stories about people who thrived despite oppression; this includes their experiences and histories/herstories for a 'more balanced gender(ed) discourse in society' (Etim, 2020: 10). This provides knowledge and inspiration to students who are vulnerable and often may feel demotivated and unable to outgrow their oppressive circumstances (Knowles, 2019: 125). This also touches on the African philosophy of Ubuntu which could serve as a means of addressing human struggles through oneness, because as Mbiti (1989: 106) defines this concept, 'I am, because we are; and since we are, therefore I am'. Key to teaching is that students learn through each other, and through this possibly re/discover themselves.

This philosophy also guides classes structured in a social constructivist manner that previous research shows links to concepts of Ubuntu, thus providing an empowering way of addressing social injustices (Schreiber & Tomm-Bonde, 2015). Indeed, Angu, et al. (2020: 7) emphasise that Ubuntu in the academic literacy class 'may aid in decolonizing both teaching practices and the dissemination of course materials'. Because it is the primary philosophy guiding African culture, knowledge, thinking and way of being, students are familiar with and embrace this way of interacting in the classroom. This is especially the case if teachers make it known why group work and similar teaching strategies, essential to social constructivism and Ubuntu, is central to learning. This allows for confidence in approaching this collaborative, collectivist, and Afrocentric environment; it empowers students and moves them away from the idea that Eurocentric knowledge is the end all and the be all (Angu, et al., 2020; Eybers, 2023; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018). In addition, as Van Aardt's (2019: 101) findings make clear: 'a need exists to stimulate student interests in reading through appropriate and user-friendly stories that appeal to their own cultural experiences, but that also promote an understanding of other cultures'. Thus, reading which is culturally relevant teaches students to value their own culture, heritage, and knowledge and to formulate their own knowledge and voices through the 'collective task to develop knowledge for the community' (Angu, et al., 2020: 7). By doing so, students move away from the idea that they do not belong in the academic world which is predominantly Eurocentric and can begin to challenge individualistic, white supremacist knowledge dominance with their own socio-cultural experiences, values, and knowledge (Angu, et al., 2020; Etim, 2020). This approach is also advocated by Rasool and Harms-Smith (2022: 9) who believe that 'transformation of its knowledge systems of colonial, masculinist and patriarchal hegemony' must occur and that one means to do this is through 'privileging the 'voice' of the silenced' and 'embracing Ubuntu without arrogating it'.

During class time, students through an intensive process reading stance are then able to engage in an analysis of themes in the literature and engage in metacognitive knowledge and reading strategies which allow for improvement in reading comprehension (Grabe & Stoller, 2019). Much of the learning process revolves around discussion, group work and peer interaction which allows for debate, enables a dialogue (Dison, 2018: 70), and critical questioning about the societal systems in place. Similarly, if students are encouraged to practice reading strategies then they have a greater chance of being able to gain insight into the texts of their own peoples; these reading strategies include previewing the text, predicting text information, studying text structures, developing fluency, skimming and scanning, vocabulary building, reading for key ideas and information, speed reading, comprehension practice, activating background knowledge, and sharing ideas, making inferences, and relating texts to real-world experience (Eybers, 2023; Grabe & Stoller, 2019). Through these reading strategies applied to texts which may be interesting and relevant, students may have more success in accessing academic texts with motivation and confidence which enables success (Grabe & Stoller, 2019: 165). Confidence is brought about, too, by being exposed to texts which students can relate to and which encourage identity formation (Eybers, 2023; Grabe & Stoller, 2019; Morse, et al., 2024: 4). In turn, this leads to reading motivation and further reading interest (Morse, et al., 2024). The theory here is that if an enjoyment of reading can be fostered by adapting the teaching materials (Stoller, et al., 2013), students have so much to gain in light of Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP) skills, which lead to critical thinking, expression of opinion and reading and writing academically (Cummins, 1981; Van Wyk, 2014). A higher reading level, through practice of reading, will lead to a higher level of self-efficacy and motivation (Boakye, 2015). This is crucial for achieving success at university level and not only to empower students' intellectual capacities, but naturally towards a 'better standard of living' (Grabe & Stoller, 2019: xvi) and even economic empowerment (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018: 18).

In addition, if students enjoy reading and find a message that they can relate to in terms of acknowledging and overcoming oppression, this is a valid research objective. However, although non-western peoples and women have been oppressed for centuries and continue to face major injustices, white maleness cannot be excluded extensively. A vast majority of the world's peoples (this word used to express both sex and race) have been oppressed and thus some western texts could prove relevant to African students, especially if they are from cultures of the oppressed/colonised as is the case for three of the readings by white authors in this reading curriculum. Western theory and texts, when used should be made relevant to students both in content and culture (Angu, et al., 2020; Grabe & Stoller, 2019; Van Aardt, 2019) which is the approach followed here. If the prescribed materials can bring about a realisation that white supremist, capitalistic and imperial injustices have been suffered on a global scale resulting in a worldwide crisis and 'international stress' (Fanon, 1965), a more balanced approach can be attained, both in terms of the written text and in terms of a world view but without subjugating another race or sex in the process. This then alludes to the main purpose of this study, which is to explore students' perceptions of decolonised, gender/Afro-centric reading content, if students perceived benefit from this in terms of social justice and empowerment, and whether motivation is increased thus leading to reading and academic skills improvement. The next section will describe research methodology and will be followed by results, discussion, and findings.

Research design and methodology

This study sought to gather data on student perceptions of a gender sensitive and decolonised reading curriculum in an academic literacy subject. An interpretivist approach embedded in critical theory was used to guide this study. An interpretivist approach was useful because data were gathered of students' perceptions in the form of subjective experiences of social phenomena (Maree, 2016: 60; Rhehman & Alharthi, 2016: 55). Because this research explored student perceptions of race, decolonisation and gender, critical theory was also used to inform the study. As Rehman and Alharthi (2016: 57) confirm, critical theory assumes that reality exists, but that it is shaped by culture, gender, political factors and the like, and that 'knowledge endorsed by those in power (politically or educationally) is to be viewed critically'. Critical theory also aims for a transformative dialogue in which participants may engage to bring about change in 'their outlook on the social systems that keep them deprived of intellectual and social need' (Rehman & Alharthi, 2016, 57). As this was the purpose of the reading curriculum, as well as because the research investigated whether students perceived a benefit from decolonised, gender sensitive material, critical theory served as an exploratory vehicle to the study.

Ethical clearance was gained for this research study as well as students' consent to participate in the survey. Full anonymity of the 298 students who participated in the survey was also maintained throughout the entire research process. Data gathered consisted of both quantitative and qualitative data gathered from a single Questback survey and thus followed a mixed-method approach. This mixed-method analysis allowed for corroboration of findings between the quantitative and qualitative data, as well as assisting with the reliability, validity, and variability of the study (Bryman, 2016; Creswell & Plano Clark, 2017). The survey consisted of 17 Likert scale questions gathering quantitative data. In addition, 13 open-ended questions were in place to gather qualitative information about Likert scale questions and thematic analysis was used as a means to interpreting qualitative data. The survey was conducted at the end of the year after students had completed their academic literacy module and thus the reading curriculum.

Results and discussion

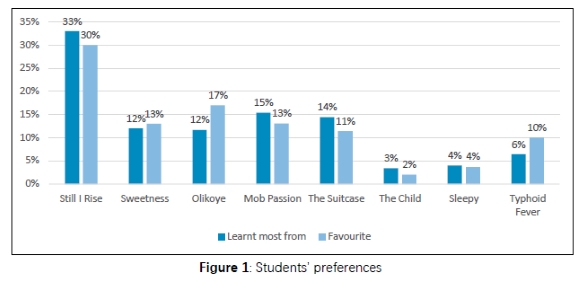

Results from the survey which measured students' perceptions of a decolonised, gender-centric reading curriculum show that in general, students perceived benefit (See Figure 1). In the discussion which follows, firstly, reading preference and the benefits of the reading curriculum in terms of social justice will be explored. Secondly, reading improvement, including interest in reading will be discussed and finally, students' perceptions of academic literacy skills improvement will be analysed. Qualitative data in the form of students' comments have also been included to corroborate quantitative data.

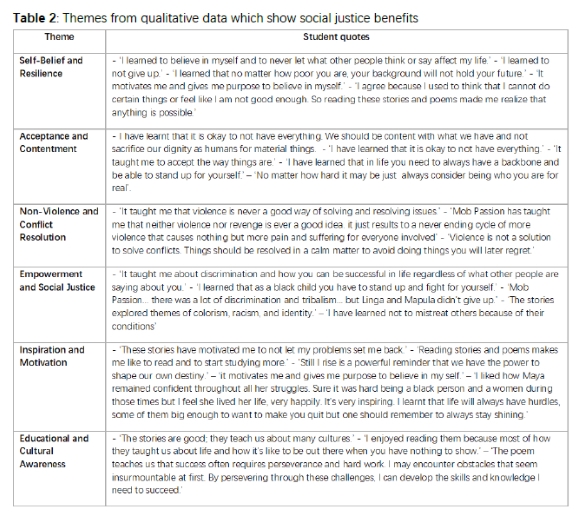

From Figure 1 regarding students' preferences, Maya Angelou's (1978) 'Still I rise' seems to be both the favourite and most learnt from text in the GENLit reading curriculum. One third of students tended to agree with this and much of the qualitative data points to students finding that they could relate to this poem and that it taught them to rise above their problems. Chimamanda Adichie's 'Olikoye' (2015) seems to be the next favourite with 17% of students choosing this as their most preferred story and 12% seeing it as one they learnt the most from. 'Sweetness' (2015) by Toni Morrison and 'Mob Passion' (1989) by Can Themba were the next favourites (13%) and stories which students felt they learnt from. Es'kia Mphahlele's (1982) 'The Suitcase' received similar results. This shows that students perceived African American female, African Nigerian female, and South African male texts to be amongst the most preferred texts. It is telling that the top three most favoured/learnt from texts are by black female writers and that ultimately, the five black authors are preferred to white authors. This shows the relevance of exposure to both female and black author's work (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2013; Knowles, 2019; Rasool & Harms-Smith, 2022). White authors' texts, whether male or female, were less preferred, although Frank McCourt's 'Typhoid Fever' (2015) was a favourite amongst 10% of students. This also seems to suggest that although students did not disfavour white authors completely, there is a preference for reading material which they can relate to, by authors of their own ethnicity, culture, and race. Therefore, this shows how important it is for students to read the works from their own peoples which is reiterated by qualitative data (Table 2) and confirmed by previous research (Angu. et al. 2020; Van Aardt, 2019). Table 2 above shows themes found in qualitative data and quotes from students. All qualitative data remains in students' own words and has not been corrected.

Themes from the qualitative data show that students perceived the following: self-belief and resilience, acceptance and contentment, non-violence and conflict resolution, empowerment and social justice, inspiration and motivation and educational and cultural awareness. The student below sums up the inspiration of poems such as 'Still I Rise' as well as the empowerment experienced as a result:

I liked how Maya remained confident throughout all her struggles. Sure it was hard being a black person and a women during those times but I feel she lived her life, very happily.

It's very inspiring. I learnt that life will always have hurdles, some of them big enough to want to make you quit but one should remember to always stay shining.

The themes found here emphasise that of previous research which calls for students' access not only to decolonised content, but also culturally relevant and empowering content which assists in motivation and learning to access reading content (Angu, et al., 2020; Grabe & Stoller, 2019; Van Aardt, 2019). The student's comment above also suggests the relevance of being exposed to black female writing and the inspiration of this to the student. Responses for this poem were dominant in qualitative data which suggests its empowering qualities.

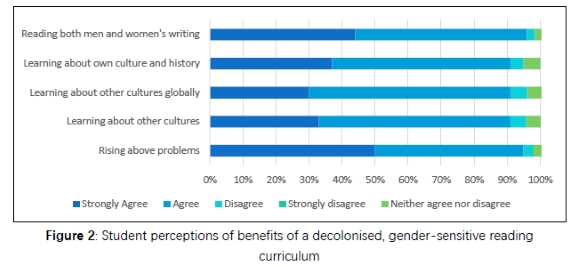

In exploring how students perceived reading material which exposed them to writers of their own culture and others, as well as the writing of both genders, students expressed positive views (in Figure 2). Over 90% of students saw the benefit of reading works of their own culture and others as relevant, thus supporting previous research (Angu, et al., 2020; Eybers, 2023). The results for reading on a global scale are similar, as well as reading both genders. Of importance to this study is that 95% of students believed that being exposed to decolonised and gender sensitive reading helped them to feel that they could overcome their problems; this is also seen in the comment above.

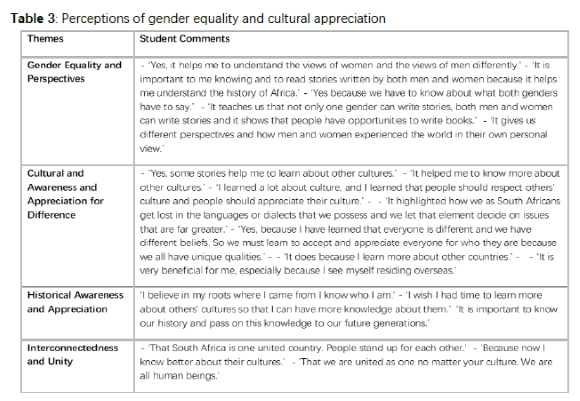

This is further corroborated by qualitative data shown below with students' perceptions in Table 3. Through thematic analysis, the following were found to be major themes: an appreciation of gender equality and different perspectives, cultural awareness and appreciation for difference, historical awareness and appreciation, and interconnected ness and unity. One student's comment reveals the presence of Ubuntu and the importance of this within a reading context:

... we are united as one no matter your culture. We are all human beings.

This points to the relevance of diverse reading material for students in support of previous research suggesting the same (Angu, et al., 2020; Van Aardt, 2019). This also suggests students' sense of belonging, inclusion, and identity which are so important in multilingual context, especially when learning occurs in the language of the coloniser (Joubert & Sibanda, 2022).

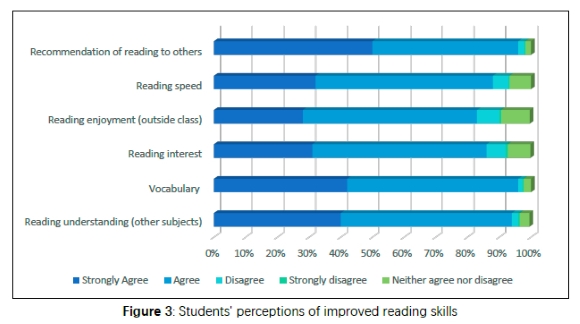

Figure 3 below shows how students, 85% and over, perceived their reading skills to have improved in terms of vocabulary improvement, reading speed, and understanding of reading material in other subjects. These are skills research has shown to be beneficial to reading improvement (Grabe & Stoller, 2019). In addition, between 80% to 90% of students agreed that their interest in reading had improved, that they had greater enjoyment of reading outside of the classroom and that they would recommend reading to others. This implies that the majority of students felt that GENLit had helped them improve reading in a beneficial way not only for the academic literacy subject, but also outside of the classroom, in other subjects and for enjoyment at home. It also shows how students believed it to be beneficial to others in the larger community and potentially this could help in creating a culture of reading within the community, which is advocated for by Morse, et al. (2024) to improve academic achievement in South African society.

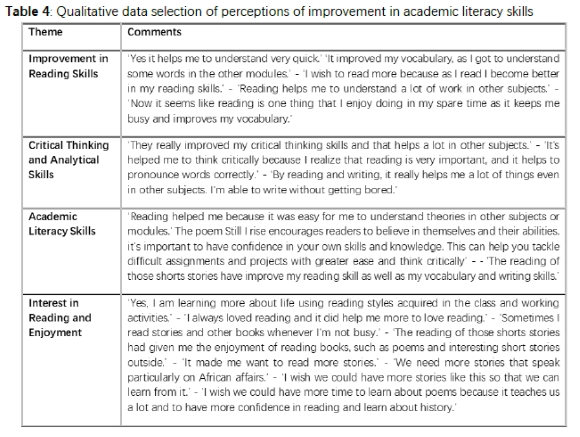

Qualitative data from students' comments (see Table 4) in the survey also reiterate the benefits students found through diverse and inclusive reading content. Table 4 shows a thematic analysis of students' comments regarding their perceptions of GENLit and how it was beneficial for reading skills and academic literacy. The themes interpreted from this data are: improvement in reading skills, improvement in academic literacy skills, reading interest and enjoyment and critical thinking and analytical skills. For example, one student stated,

It helped ... I will say I was lazy to read before but now I enjoy reading a lot

This shows improved motivation to read, thus assisting with reading proficiency and self-efficacy required for university (Boakye, 2015). Another student commented that 'reading helped me develop new skills to focus and understand work in other subjects', and a third student felt that 'it has helped read and understand long content'.

These student comments imply skills transfer, especially when it comes to understanding the content of other subjects, in one case with long reading matter, which is important for academic achievement (Grabe & Stoller, 2019). These are important attributes in being able to read at university level, and to manage the demands of university expectations (Adjei-Mensah, et al., 2022).

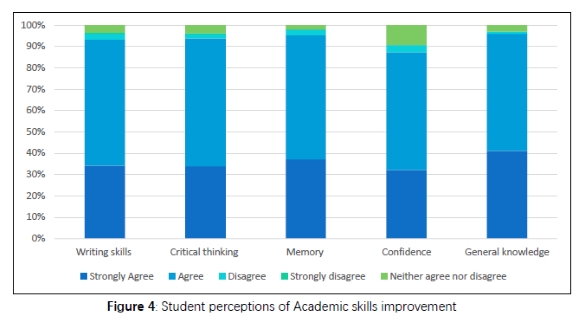

Finally, Figure 4 reveals how students perceived a general improvement in academic literacy skills which confirms previous research about how reading, writing, and academic literacy are intertwined and necessary for academic success (Grabe & Zhang, 2016). When it came to critical thinking, writing skills, memory, and general knowledge, at least 90% of students were in agreement that these skills had improved; 85% of students believed confidence had also improved; this is also a factor crucial to reading, self-efficacy, and academic improvement (Boakye, 2015; Grabe & Stoller, 2019). Comments from students reiterate quantitative data. For example:

t]hrough reading, I learned how to write.

I can solve a problem and explain things in more details.

This points to confidence, critical thinking, and problem solving, all of which are skills needed for university success (Grabe & Stoller, 2019).

Quantitative and qualitative data show that through an approach that aims at transformation through texts which are socially just, students may feel a sense of empowerment. This occurs both through content which is socially just and through practical engagement with this content. This is in line with what Dison (2018: 67) confirms of the transformative approach which aims 'to reduce inequalities in society' and 'initiates students into powerful knowledge and ways of knowing as well as providing students with the academic literacies to engage with and critique knowledge'.

Recommendations

Based on this research, it is possible to introduce, through redesign of a curriculum, a decolonised and gender-centric reading curriculum to an academic literacy module. In this case, the research aim was to investigate whether students perceived a benefit from reading Afro/gender-centric material and also whether reading skills and academic literacy skills improved. Most students perceived this to be an empowering experience and one in which they felt they could more easily overcome problems, including those of gender and race discrimination amongst other forms of oppression. Students benefit because instead of only accessing largely white and male-dominated texts, they have a larger variety to choose from. In turn, this could promote student success, because it assists students in being able to navigate texts which are often received by them as being alien to their plight. In taking a more balanced approach and seeking similar themes of oppression and poverty and how to rise above this, students are furthermore, given skills to navigate the many prejudices they are faced with on a daily basis.

Recommendations, therefore, are that academic literacy practitioners attempt to provide students with this type of experience through the content or reading material of their curriculum and thus supports calls for decolonisation of the curriculum. In addition, methods for teaching and learning pedagogy should allow for Afrocentric learning, such as bringing the philosophy of Ubuntu into the classroom.

Future research could investigate whether students' reading proficiency improves through pre- and post-testing, as well as by conducting interviews and focus groups with students to explore their perspectives on a reading course such as this one. This might also reveal more shortcomings but also ways to approach the youth of today through a reading format which would benefit their academic skills and future success. These methods may also assist in finding more ways to diversify academic literacy curricula in future. In addition, more stories and texts could be included as this was something quite a few students requested in the survey.

Conclusion

This research has focussed on students' perceptions of a gender/Afro-centric reading curriculum in an academic literacy subject. Findings show that students felt that they benefitted not only in reading improvement, but also in other academic literacy skills such as academic writing and critical thinking. Of utmost importance, is that in general, students felt that they benefitted from exposure to themes of empowerment such as race and gender equity. If students perceive both benefit from questioning systems of oppression through analysis of reading material, and by improving reading skills, then this implies that a decolonised and gender-equal reading curriculum can lead to empowerment. That the preferred reading texts are by predominantly black female authors, suggests that students, both male and female, might be more open to reading matter of this type. In addition, 'Still I rise' was by far the anthem of choice for many students and because it addresses directly a way in which all peoples may find liberation, this suggests that students might have found a practical way to finding empowerment. Furthermore, this research suggests a way forward in both assisting students' reading improvement and academic literacy skills in general, whilst providing a practical way to decolonise/'de-gender' an academic literacy curriculum.

Author Biography

Linda Sparks is a Lecturer/Researcher and Academic Literacy Coordinator on Access Programmes at Academic Language and Literacy Development, at the University of the Free State. Research interests include blended learning, innovation in teaching and learning, curriculum design, social justice, decolonisation, gender studies, language acquisition, and language and literature studies.

References

Adichie, C. 2015. Olikoye. Matter. Available at: https://medium.com/matter/olikoye-b027d7c0a680 (Accessed: 17 May 2024).

Adjei-Mensah, S. Boakye, N. & Masenge, A. 2023. Improving the reading proficiency of mature students through a task-based language teaching approach. Reading & Writing, 14(1), 406. [ Links ]

Angelou, M. 1978. Still I rise. And Still I Rise. London: Little, Brown Book Group, 46-47.

Angu, P., Boakye, N. & Eybers, O. 2020. Rethinking the teaching of academic literacy in the context of calls for curriculum decolonization in South Africa. The International Journal of Pedagogy and Curriculum, 27(1): 1-16. [ Links ]

Ayyildiz, N. & Koçsoy, F. 2020. Elethia and A sudden trip home in spring: Alice Walker's womanist response to the issues of black people. Journal of Social Sciences, 34: 26-48. [ Links ]

Boakye, N. 2015. The relationship between self-efficacy and reading proficiency of first-year students: An exploratory study. Reading & Writing, 6(1): 52. [ Links ]

Bryman, A. 2016. Social Research Methods. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Chekhov, A. 2000. Sleepy. Selected Stories of Anthon Chekhov. New York: Random House, 45-49.

Creswell, J. & Plano Clark, V. 2017. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 3rd edn. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Cummins, J. 1981. Age on arrival and immigrant second language learning in Canada. A reassessment. Applied Linguistics, 2(2): 132-149. [ Links ]

Daniels, J. 2022. Alternative feminism: Interrogating marriage and motherhood in Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie's Half of a Yellow Sun and Purple Hibiscus. The International Journal of Humanities Education, 21(1): 53-66. [ Links ]

Dison, A. 2018. Development of students' academic literacies viewed through a political ethics of care lens. South African Journal of Higher Education, 32(6): 65-82. [ Links ]

Etim, E. 2020. "Herstory" versus "history": A motherist rememory in Akachi Ezeigbo's The Last of the Strong Ones and Chimamanda Adichie's Half of a Yellow Sun. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 7(1): 1728999. [ Links ]

Eybers, O. 2023. Afrocentricity and decoloniality in disciplinarity: A reflective dialogue on academic literacy development. Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning, 11(2): 48-64. [ Links ]

Fanon, F. 1963. The Wretched Earth. New York: Grove Books. [ Links ]

hooks, b. 2013. Writing Beyond Race: Living Theory and Practice. New York: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Gouws, A. 2017. Feminist intersectionality and the matrix of domination in South Africa. Agenda. 31(1): 19-27. [ Links ]

Gouws, A. & Coetzee, A. 2019. Women's movements and feminist activism, Agenda, 33(2): 1-8. [ Links ]

Grabe, W. 1991. Current developments in second language reading research. Tesol Quarterly, 25(3): 375-406. [ Links ]

Grabe, W. & Stoller, F. 2019. Teaching and Researching Reading. 3rd edn. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Grabe, W. & Zhang, C. 2016. Reading-writing relationships in first and second language academic literacy development. Language Teaching, 49(3): 339-355. [ Links ]

Jonker, I. 2007. The Child. In Brink, A. & Krog, A. transl. Black Butterflies. Cape Town: Human and Rousseau, 85.

Joubert, M. 2024. The liminal space: Academic literacies practitioners' construction of professional identity in the betwixt and between. London Review of Education, 22(1): 1-15. [ Links ]

Joubert, M. & Sibanda, B. 2022. Whose language is it anyway? Students' sense of belonging and role of English for higher education in the multilingual, South African setting. South African Journal of Higher Education, 36(6): 47-66. [ Links ]

King, M. 1967. A Christmas Sermon on Peace. Available at: http://mseffie.com/assignments/invisible_man/Christmas%20Sermon%20on%20Peace.pdf (Accessed: 22 May 2024).

Knowles, C. 2019. Access or a set up? A critical race feminist, black consciousness, and African feminist perspective on foundation studies in South Africa. Alternation, 26(2): 117-137. [ Links ]

Mabasa, K. 2017. The rebellion of the born unfrees: Fallism and Neo-Colonial corporate university. Strategic Review for Southern Africa, 39(2): 94-116. [ Links ]

Marais, F. & Hanekom, G. 2014. Innovation in access: 25 years of experience in access programmes. Annual Teaching and Learning Report 2014: Moving the Needle Towards Success. University of the Free State: Centre for Teaching and Learning, 10-12.

Maree, K. 2016. First Steps in Research. 2nd edition. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

McCourt, F. 1996. Typhoid Fever. In Angela's Ashes. Schribner: New York, 187-195.

McWilliams, R. & Allan, Q. 2014. Embedding academic literacy skills: Towards a best practice model. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 11(3): 1-14. [ Links ]

Morrison, T. 2015. Sweetness. God help the child. Knopf: New York. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/02/09/sweetness-2 (Accessed: 21 May 2024).

Morse, K., Ngwato, T. & Huston, K., 2024. Reading cultures - Towards a clearer, more inclusive description. Reading & Writing, 15(1): 1-7. [ Links ]

Mphahlele, E. 1981.The Suitcase. In The Unbroken Song. Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 15-23.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. 2013. Perhaps decoloniality is the answer? Critical reflections on development from a decolonial epistemic perspective. Africanus, 43(2): 1-11. [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. 2018. The dynamics of epistemological decolonisation in the 21st century: towards epistemic freedom. Strategic Review for Southern Africa, 40(1): 16-45. [ Links ]

Ndimande, B. 2013. From Bantu education to the fight for socially just education. Equity and Excellence in Education, 46(1): 20-35. [ Links ]

Rehman, A. & Alharthi, K. 2016. An introduction to research paradigms. International Journal of Educational Investigations, 3(8): 51-59. [ Links ]

Rasool, S. & Harms-Smith, L. 2022. Retrieving the voices of black African womanists and feminists for work towards decoloniality in social work. Southern African Journal of Social Work and Social Development, 34(1): 1-30. [ Links ]

Schreiber, R. & Tomm-Bonde. 2015. Ubuntu and constructivist grounded theory: an African methodology package. Journal of Research in Nursing, 20(8): 655-664. [ Links ]

Sekonyela, L. 2023. Academic writers as interdisciplinary agents in the University Access Programme. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies, 3: 89-102. [ Links ]

Silverthorn, R. 2009. Tradition or transformation: A critique of English setwork selection (2009-2011). Unpublished MA diss. University of the Witwatersrand: Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Stoller, F., Anderson, N., Grabe, W. & Komiyama, R. 2013. Instructional enhancements to improve students' reading abilities. English! Teacher Forum, 1: 1-33. [ Links ]

Themba, C. 1989. Mob Passion. In Chapman, M. (ed.). The Drum Decade: Stories from the 1950s. KwaZulu-Natal: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 32-38.

Van Aardt. P. 2019. Using students' creative writing towards decolonising an Academic Literacy curriculum. Journal of Decolonising Disciplines, 1(2): 87-103. [ Links ]

Van Wyk, A. 2014. English-medium education in a multilingual setting: A case in South Africa. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 52(2): 205-220. [ Links ]

Vygotsky, L.S. 1962. Thought and Language. Cambridge: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Walker, A. 1983. In Search of our Mothers ' Gardens. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Corresponding author:

SparksLA@ufs.ac.za

Submitted: 22 May 2024

Accepted: 18 November 2024