Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

African Human Mobility Review

On-line version ISSN 2410-7972Print version ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.7 n.3 Cape Town Sep./Dec. 2021

ARTICLES

The Dynamics of Child Trafficking in West Africa

Samuel Kehinde Okunade; Lukong Stella Shulika

University of Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The phenomenon of human trafficking remains a scourge in Africa, and this continent continues to be a source and transit route for this illicit activity. The West African region has perpetually maintained the undignified position as the region with the most prevalent issues of human trafficking, child labor, and modern slavery, despite the efforts by the various national governments and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to eradicate these atrocities. This study examines the efforts of the West African states towards tackling this menace of trafficking across West African borders. The study employed a documentary research design and retrieved data from both primary and secondary materials. Findings from the study showed there is still a lacuna in the domestication of the United Nations (UN) Protocol on Human Trafficking by West African states as the West African Network of Central Authorities and Prosecutors (WACAP) against Organized Crime, saddled with harnessing the resources of ECOWAS states in combating the menace, lacks the capacity required for achieving the set goal. Also, efforts by the various states in the region have been largely reactive and legislative rather than preventive. The study thus recommends that ECOWAS states take preventive measures, like building the institutional capacities of regional and national law enforcement, as well as implementing measures that will ensure respect for the fundamental human rights of women and children in the sociocultural philosophies of West Africans.

Keywords: human trafficking, child trafficking, West African States, ECOWAS, child labor

INTRODUCTION

Human trafficking as a concept and practice is as dated as the literature on it. Such literature tends to problematize human trafficking broadly from a human rights lens and assumes a marked critique of stakeholders involved in it and governments with weak policies that feed it (Laczko and Gramegna, 2003; Cullen-DuPont, 2009; Shelley, 2010; Wheaton et al., 2010; Farrell and De Vries, 2020). However important this phenomenon and problem is, human trafficking is currently a source of conflict intractability and a source through which violent extremist groups recruit vulnerable and helpless mercenaries (Hynes et al., 2018). Another dimension is the cultural and religious driver of human trafficking (De Liévana and Montánez, 2015; Ikeora, 2016). This is hinged on the fact that certain cultural and religious practices permit the initiation and utilization of children to advance their ideologies. For instance, the alamajiris of Northern Nigeria, the mendiants of Mali and Senegal or the street children of The Gambia and Niger are organized cults of kids answerable to a master in whose hands and on whom their destiny and survival depends (Andrew and Lawrance, 2012; Gunther, 2021; NAPTIP, 2021).

These children, often victims of poor social systems, poverty, and illiteracy join fundamentalist groups with the expectation that such group leaders will educate them out of their plight and grow them into religious, cultural or community leaders (De Liévana and Montánez, 2015; Gunther, 2021; NAPTIP, 2021). The widely accepted belief that children sent to learn a trade from an influential person is beneficial to their families in the long run, fuels voluntary and cooperative trafficking, which is different from children seized as booties of conflicts, including Boko Haram, that currently wreaks havoc in Chad Basin today (Hynes et al., 2018; EASO, 2021; NAPTIP, 2021). This paper discusses the complexities of human trafficking with a particular emphasis on child trafficking in West Africa, its societal acceptance, and the broader impact of the practice on regional peace and security. The paper assesses the efficacy of measures taken by states and the ECOWAS regional block to deal with the scourge. Acknowledging the complexity of the issues, the paper navigates a careful line of recommendations, which suggest that human trafficking is bad for all (including its promoters).

LITERATURE REVIEW: TRAFFICKING AS A GLOBAL ILL AND HUMAN SECURITY CHALLENGE IN AFRICA

Human trafficking has over the years proven to be a global menace not limited to a specific geographical location, region, or continent (IOM, 2017; UNODC, 2021). Traceable to the 1980s, several reasons have been put forward as the root cause of global trafficking, including developments in migration trends, the AIDS pandemic, the feminist movement, child prostitution, and sex tourism - all of which characterized the 1980s and the dire economic situation of many countries (Doezema, 2002; UNODC, 2017, 2020, 2021). Globalization, which has led to the demand of cheap labor in the industrialized climes, has also been identified as a major cause of and contribution to human trafficking (IOM, 2017; UNODC, 2017). Despite the attention and resources that this phenomenon has attracted from international and local state and non-state actors, the number of victims of human trafficking keeps increasing globally (IOM, 2017). The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2020 report observes that as at 2018, global statistics on victims of human trafficking stood at 49,032 people, while victims by age and gender were at 48,748, and another 39,805 people were reported to be victims of one form of exploitation or another (UNODC, 2021).

Furthermore, while 9,429 persons had been investigated and suspected of trafficking-related crimes, only 7,368 have been prosecuted and only 3,553 have been convicted (UNODC, 2021). As identified by global reports and scholars, trafficking is carried out for the purpose of exploitation, which is classified into two forms, namely, for forced labor and for sexual exploitation (IOM, 2017; UNODC, 2017, 2020, 2021; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). Although sexual exploitation has received much attention, since many females are trafficked for that purpose, the incidence of forced labor has equally grown, due to the massive demand for cheap labor across the globe (ILO, 2012a; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). Scholars have identified three prevalent types of trafficking in sub-Saharan Africa: (a) trafficking in children for farm labor and domestic work within and between countries; (b) trafficking in women and young persons for sexual exploitation, majorly outside the region; and (c) trafficking in women from outside the region for the sex industry in South Africa (Sita, 2003; Gould, 2011; Kreston, 2014; Deane, 2017; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021).

The need for cheap domestic and agricultural labor in Africa explains the rising number of male victims, as raised by reports on human trafficking (ILO, 2017; IOM, 2017; Statista, 2021). Trafficking in persons grossly violates the fundamental rights of women and children who form the majority of trafficked persons among the vulnerable groups (Deane, 2017; ILO, 2017; IOM, 2017; UNODC, 2017, 2020). As scholars have argued, there is a thin line between trafficking, irregular migration, and smuggling in persons, as traffickers engage in irregular travel patterns across countries and continents in an attempt to evade authorities and deliver their cargoes to their destinations undetected (Deane, 2017; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021; Okunade, 2021). There have been extensive debates in the reliability of sources of data on the trends and statistics of trafficking in persons, resulting in figures usually being estimates and approximations. According to recent estimates, approximately 12.4 million people are being trafficked across the globe annually, while 80% are believed to be women, 70% of whom are trafficked for sexual exploitation (Gould, 2011; Ikeora, 2016; Deane, 2017).

Global statistics indicate that between 2008 and 2019, the estimated number of trafficked victims from sub-Saharan Africa increased from 30,961 to 105,787 (Statista, 2021) while the UNODC 2020 report states that child victims amounted to one-third of the global population of trafficked persons - taken from their countries to within and beyond their countries for various forms of exploitation (ILO, 2012b; Kreston, 2014; UNODC, 2021). Reports also indicate that within Central and West Africa, between 200,000 and 300,000 children are trafficked for sexual exploitation and forced labor, with 99% of this number trafficked within the African region (ILO, 2012a; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). Alarmingly, more than 50% of human trafficking victims in West Africa are children (Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). According to studies conducted in 2011 on child labor in Central and West Africa, more than 1.8 million children were reportedly working on cocoa farms in Cameroon, Cote d'Ivoire, Nigeria and Ghana (ILO, 2012a). Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire were reported to host the highest number of child laborers working on the farms, with a combined estimation of 1.8 million children, making West Africa the region with the highest number of child laborers in the world (ILO, 2012b; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021; UNODC, 2021). According to the Global Slavery Index, Nigeria ranks 32nd out of 167 in nations with the highest number of slaves, with an estimated 1,38 million slaves, most of whom are child laborers (Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021).

During the late 1990s, when global trafficking was rife, the United States took the lead in establishing governance measures to contain this phenomenon (Gozdziak and Collett, 2005). This led to the establishment and promulgation of protocols aimed to protect trafficked victims. Such measures include the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) of 2000 and the Trafficking Victims Protection Re-authorization Act of 2003, regarded as the major tools for combating human trafficking globally and locally (Gozdziak and Collett, 2005). Mexico is known as a country of source, transit and destination for trafficked persons for the purpose of sexual exploitation and forced labor (Gozdziak and Collett, 2005; IOM, 2017). However, the country has contributed little to the efforts aimed at combating this scourge locally and within North America. The Trafficking in Persons (TIP) report indicated that the Government of Mexico defaulted in observing the minimum standards for combating trafficking (Thompson, 2003). In South Asia, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka are major source countries for trafficking while India and Pakistan are the major destination countries, while they also serve as transit points for some countries in the Middle East (Ali, 2005). Women and girls are trafficked to countries in the Persian Gulf (Ali, 2005). In Bangladesh, women and children are trafficked purposely for forced labor, sexual exploitation, camel jockeying, domestic service, sale of organs, and forced marriage (Bangladesh Counter Trafficking Thematic Group, 2003).

Africa - and specifically the West African region - has not escaped this menace, as reports and statistics show that many West African states serve as countries of source, transit and destination for trafficking in persons, thus increasing the rate of the activity within the sub-region (Obokata, 2019; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021; Okunade, 2021). As already noted above, West Africa accounts for the highest number of trafficked humans and child laborers in sub-Saharan Africa, according to reports by the International Labour Organization (ILO), the United Nations (UN) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Trafficking takes different forms depending on the countries involved and the demands made (Deane, 2017). For instance, in the Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Mali, and Senegal, child trafficking is carried out for purposes of labor, prostitution, street begging, and child pornography (UNODC, 2020; Gunther, 2021), while in other West African countries such as Benin, Ghana, Togo, Cote d'Ivoire, and Nigeria, child trafficking takes place majorly for the purpose of child labor (HRW, 2019; UNODC, 2020).

Several factors have been adduced for the phenomenal increase in trafficking in persons across the continent. According to studies on this social menace, poverty and increased unemployment levels are fundamental factors leading to increased TIP in Africa generally and in West Africa specifically (Gould, 2011; Kreston, 2014; ILO, 2017; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021; UNODC, 2021). The US Department of State also noted that poor economic conditions provide fertile ground for traffickers and smugglers to lure vulnerable people by making false promises of higher salaries and better working conditions in foreign countries (USDoS, 2013; Okunade, 2021). Directly linked to this, is the non-existent welfare support system in most African countries that makes it difficult for parents to adequately meet the economic and welfare needs of their families (Gould, 2011; Kreston, 2014; Deane, 2017). The result of these poor economic conditions in many African countries is that parents are compelled to either offer their children for sale, or to exchange them for debts to traffickers to pay back debts, in their attempts to escape poverty (UNODC, 2020, 2021).

The lack of education - characteristic of many African countries - that has resulted in the multiplication of out-of-school children with little or no socioeconomic value, has also contributed in no small way to child trafficking (Mensah-Ankrah and Sarpong, 2017; USDoS, 2021). Major towns and cities across African countries reportedly host large numbers of such out-of-school children who eventually become street beggars, hoodlums, street urchins, etc. with adverse socioeconomic implications for society (Mensah-Ankrah and Sarpong, 2017; USDoS, 2021). Cultural and religious practices have also been identified a playing an active role in fostering trafficking across the world, especially in African countries (Sawadogo, 2012; Deane, 2017; USDoS, 2021). As noted by researchers, the cultural belief of family solidarity and tribal affiliation practices put many children at risk of being trafficked because this system encourages parents to willingly hand over their children to close and distant relatives and friends with little or no access to the welfare of these children (Sawadogo, 2012; Deane, 2017).

The leeway created by this traditional and cultural interaction, allows for many children to be trafficked with relative ease, especially when children are taken to destinations far from their parents (UNODC, 2021; USDoS, 2021). Scholars acknowledge that this practice is rampant in most West African nations (Sawadogo, 2012; Deane, 2017; Dajahar and Walnshak, 2018). Studies also revealed that in some African countries like Kenya, Zimbabwe, and Ghana, there are several misplaced cultural beliefs that have gendered implications. For example, the belief that having sex with virgins serves as an antidote to diseases such as HIV/AIDS, usually leads to young girls becoming victims of trafficking, sex slavery and early marriages (Ikeora, 2016; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021).

The porosity of national borders, coupled with corrupt border security personnel have also been identified as major contributors to the increase in trafficking in persons in Africa (Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021; Okunade and Oni, 2021). The West African region in particular, and the African continent at large, are notorious for their very porous land and maritime borders, making the influx of transnational criminal networks and related actors rampant in the region (Mensah-Ankrah and Sarpong, 2017; Dajahar and Walnshak, 2018). Traffickers and smugglers have mastered the art of manoevering these porous borders either through the numerous illegal routes or with the assistance of the border guards who are usually technically and professionally ill-equipped for their job roles (Ikome, 2012; Onogwu, 2018). Reports by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC, 2021) also observed that security personnel and immigration officers have equally aided the free passage of trafficked victims along major air routes, which explains the European authorities' awareness of the entry of some trafficked persons into Europe, through the airports (EASO, 2021).

Trafficking in persons is one of the biggest sources of revenue of organized crimes, hence the proliferation in the number of traffickers and the consolidation of trafficking and smuggling syndicates and networks around the world (Sawadogo, 2012). Recent data puts the trafficking industry in Africa at a financial value of $13.1 billion per year (Okenyodo, 2020; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). Furthermore, reports indicate that successfully trafficking a woman to Europe from Africa for sex-work purposes, may cost about $2,000 which is used for procuring travel documents, bribing key officials, and transportation (UNODC, 2021). However, on getting to the intended destination in Europe, the trafficker may get up to $12,000 for every trafficked female (Sawadogo, 2012; UNODC, 2021). Reports also show that for children - depending on the source country, destination and purpose - a trafficker may earn between $50 and $1,000 for every child delivered to buyers in Europe (Sawadogo, 2012; UNODC, 2021). Sawadogo (2012) further observes that in the United States, a trafficker earns between $10,000 and $20,000 for every African child successfully delivered to buyers.

TRENDS, SOURCES AND FORMS OF TRAFFICKING IN WEST AFRICA

The West African sub-region is a major trafficking region in sub-Saharan Africa with trafficking networks spanning countries within and outside the sub-region (Deane, 2017; Okunade, 2021). As a result of this, wide links involving transnational criminal syndicates in Europe, and trafficking networks within the West African sub-region to Europe have become increasingly sophisticated and continue to thrive, with several major cities and towns - such as Benin City in Southern Nigeria - dubbed as notorious trafficking hubs (UNICJRI, 2003; Shelly, 2014; HRW, 2019). Victims of these sophisticated criminal networks, which reportedly include migration and border officials, are then ferried to Europe through the various land, sea, and air corridors in major cities across West African states (UNICJRI, 2003; Deane, 2017; EASO, 2021; Okunade, 2021). According to Gunther (2021), Mali serves as a major prostitution hub as well as a transit country for traffickers and illegal migrants from West Africa. The same transit routes for illegal migrants and human traffickers have been established in countries like Sierra Leone, Cote d'Ivoire, and Burkina Faso, amongst others (HRW, 2019; UNODC, 2020; Gunther, 2021).

The literature has further established that women and girls are the major victims of trafficking in the West African sub-region, as they are mostly forced into sex slavery and prostitution (UNICRU, 2004; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021; UNODC, 2020, 2021). Women trafficked from Sierra Leone and war-ridden Liberia are victims of forced prostitution and sex slavery in neighboring Mali while women in Mali are trafficked to Cote d'Ivoire, Burkina Faso and eventually to France for similar purposes (Gunther, 2021). These women are trafficked through the land and maritime borders within West Africa either to northern Africa where they are shipped through the Mediterranean Sea, or smuggled through airports to Europe where they are delivered to brothel owners (Sawadogo, 2012; Mensah-Ankrah and Sarpong, 2017; Okunade, 2021). The trajectory of these illegal journeys from West Africa through the North African cities is fraught with risks for trafficked persons -traffickers could get stranded in the Maghreb region for four or more years on their way to Europe, especially when they run out of resources or when law enforcement agencies intensify their investigations and tracking of such criminal groups (EASO, 2021; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021; UNODC, 2021; USDoS, 2021).

Similar trafficking in persons has also been reported in Ghana where both women and children are victims of trafficking networks (Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). Trafficking along this region takes place in both external and internal directions; while some victims (women and children) are trafficked within the country and the West African region (Anarfi, 1998; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021; USDoS, 2021), others are trafficked to Europe for prostitution and forced labor (ILO, 2017; IOM, 2017; UNODC, 2021). Ghana also serves as a transit route for Nigerian women trafficked to Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands for prostitution (HRW, 2019; USDoS, 2021). Other forms of internal trafficking known to occur within the West African sub-region, are Togolese young women trafficked for prostitution to the neighboring countries of Cote d'Ivoire, Ghana, and Gabon and externally to Lebanon (Taylor, 2002; USDoS, 2021). In the same vein, reports also indicate that Senegal serves as both a source and transit country for trafficked women from other West African countries to South Africa, Europe, and the Gulf States solely for prostitution purposes (Gould, 2011; Kreston, 2014; Deane, 2017).

Perspectives on the trafficking of children, women and vulnerable groups in West Africa

Along with the trafficking of women and girls, reports show that child trafficking is on the rise in West Africa (EASO, 2021; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021; UNODC, 2021). According to recent statistics by the ILO, there were about 1.8 million children trafficked in the last five years from West Africa, despite global efforts against this menace (Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). Trafficked children are mostly sourced from the rural areas where the people are naïve and desperate to escape economic hardship and predicament and strive to provide better living options for their offspring (Deane, 2017; Okenyodo, 2020). These poor economic conditions put desperate parents in a vulnerable state, especially for those in rural areas where the necessary information on the dangers of trafficking is not available (Sawadogo, 2012; Mensah-Ankrah and Sarpong, 2017). It is important to note that, according to the ILO (2017), in collaboration with the Walk Free Foundation, parents do not give their children away with the intention of selling them, even though it eventually turns out to be the case for many who may never see their children again. Most parents give their children to recruiters with the belief that they are ensuring a good life for the children and themselves, which explains why some parents accept money from recruiters with the understanding that they will receive a monthly remittance (ILO, 2012a; USDoS, 2021).

Mlambo and Ndebele (2021) identified six forms of child trafficking in Central and West Africa. These include, abduction of children; payment of sums of money to poor parents who give their children away, based on the promise that they would be treated well; bonded placement of children as debt reimbursement; placement for a token sum for specified period; for gift items; and enrolment for a fee by an agent for domestic work at the request of the children's parents (Sawadogo, 2012; ILO, 2012a, 2017; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). Mlambo and Ndebele (2021) note that in the sixth form, parents of the domestic workers are lured into releasing their children after being assured of their enrolment in schools, and trade or training institutions; meanwhile, they end up as domestic servants and street vendors. Another factor recognized by the United States Department of State that aids the release of children by their parents and even the victims themselves, is the 'smooth-talking' ability of trafficking and smuggling agents that makes it easy to convince potential victims and their parents to take custody of their wards (UNODC, 2021; USDoS, 2021). According to Dottridge (2002), traffickers have mastered the art of getting into the psyche of their victims by painting scenarios of beautiful lives in foreign cities for potential victims. This way, trafficked and smuggled women are sourced, with promises of job opportunities and better lives in Europe and in the Gulf States (Okunade, 2021).

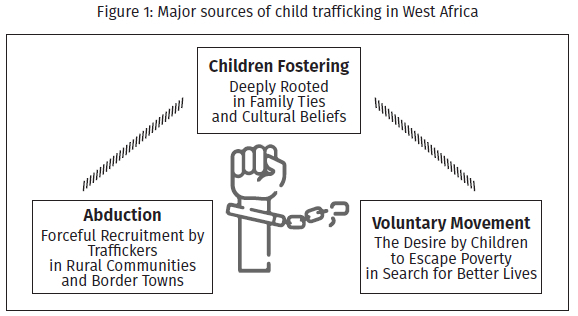

Another avenue for attracting and adopting children for trafficking from various states in Africa and in particular the West African sub-region, is through civil unrests, armed conflicts, and civil wars that are rampant within the sub-region (Dajahar and Walnshak, 2018; Okenyodo, 2020). The displacement and chaos arising from armed conflicts, civil unrests, and other internal and regional security challenges - such as the Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria, the political unrests in Mali, and Guinea, amongst others - also serve as opportunities for child traffickers who take advantage of the chaos to adopt, lure, and smuggle children (Okenyodo, 2020; USDoS, 2021). Children are trafficked for various reasons, ranging for domestic reasons to child labor, which are rampant in West African states (ILO, 2012a, 2012b, 2017; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021; Okunade, 2021). Although there are international and national legislations in many West African countries guiding the enforcement of measures against child abuse and child labor, the evidence shows that many nations within the sub-region continue to subject minors to child labor (Mensah-Ankrah and Sarpong, 2017; Aniche and Moyo, 2019). The primary trafficking source countries in the region, such as Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Mali, Nigeria, Mauritania, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Cote d'Ivoire, Congo, and Togo still record considerable numbers of children trafficked within and beyond their countries for domestic work purposes (HRW, 2019; Gunther, 2021). Specifically, Togolese girls are trafficked for both sexual exploitation and forced labor within the country and to the neighboring countries of Benin, Nigeria, Niger, and Gabon, while boys are trafficked for labor in plantations across Benin, Nigeria, and Cote d'Ivoire (Sawadogo, 2012; HRW, 2019). On the external flow of child trafficking from the West African sub-region, the Human Rights Watch (2019) notes that children from Nigeria have been trafficked to European nations such as France, the Netherlands, Spain, and some Gulf States. On the continent, Senegal has been identified as a destination country for children trafficked from Guinea Conakry, and Mali (Gunther, 2021; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). In summary, Figure 1 below encapsulates the trajectories on the sources of child trafficking in West Africa.

Child trafficking in Africa and in particular in the Western sub-region has its attendant effects on trafficked children and the sub-region at large, ranging from exposure to crime, drug abuse, and loss of cultural values - which form the basis of core African belief systems - to exposure to health hazards and diseases, and gross abuse of their fundamental human rights (Sawadogo, 2012; Mensah-Ankrah and Sarpong, 2017; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). Trafficked children eventually lose family support systems, which puts them in a vulnerable state - a situation which traffickers and their bosses exploit (ILO, 2017; IOM, 2017; UNODC, 2021; USDoS, 2021). This process breeds fear in the victims, eroding their courage to report the traffickers and turn themselves in to the appropriate authorities for help (UNODC, 2020, 2021). This is compounded by the fact that traffickers are well connected, as they have informants and support from some government officials (EASO, 2021; UNODC, 2021). Furthermore, child trafficking jeopardizes parental control and the attendant transfer of knowledge and cultural values to children, considered the cornerstone of many African societies (Sawadogo, 2012; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). There is also the potential of exposing trafficked children to vices such as crimes, alcoholism, and drug abuse which eventually result in many West African young people (primarily males) becoming drug peddlers, street beggars, and armed robbers (ILO, 2017; UNODC, 2021) which add to the social unrests already bedeviling the region.

Another crucial concern, is the danger of health hazards, emanating from the exposure of trafficked persons and children to harsh working conditions and poor nutrition (ILO, 2012a, 2017). For women and children who are sexually exploited, the exposure to sexually transmitted infections and diseases such as HIV/AIDS, is an ever-present threat to their health (ILO, 2012a; Aniche and Moyo, 2019). According to the UNODC, some trafficked children experience sexual abuse by their traffickers en-route to their destination cities/countries or by their hosts, making them vulnerable to various health hazards; others are exposed to similar health hazards by being prostitutes and street kids (Mensah-Ankrah and Sarpong, 2017; UNODC, 2021). Fitzgibbon (2003) maintains that trafficked children and child laborers in Africa are prone to suffering sunstroke; abnormal heart rhythms; and poisoning from inhaled chemicals and dust from factories, sawmills, mines, etc., all of which lead to stunted growth that makes them susceptible to malaria and other ailments.

The fact remains that these are the kinds of jobs that trafficked children are used for in West Africa. While it is unclear why any parent would be comfortable having their child hawking in the street at night, this bears evidence of the desperation experienced by vulnerable families.

In essence, child trafficking is a great violation of children's fundamental rights, especially as they are mostly dependent on their guardians for protection and provisions (ILO, 2017). Studies show that some of the instances of harsh working conditions that trafficked children are exposed to in West African countries, include, the harsh working conditions of child laborers in plantations in Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire, and in mines in Burkina Faso, Liberia and Sierra Leone where it is alleged that children are forced to work between 10-20 hours daily without the required nutritious meals (ILO, 2012b; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). This denies them access to education in their formative years - opportunities which may never present themselves again in their lifetime.

INTERNATIONAL CONVENTIONS AGAINST HUMAN TRAFFICKING

Human trafficking, especially in women and children, became a priority for the UN General Assembly and the Commission of Human Rights in the early 1990s and this led to the World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna and the World Conference on Women in Beijing in the 1990s (Gozdziak and Collett, 2005). These conferences, dedicated to addressing trafficking in persons at the global level, resulted in the promulgation of conventions and protocols, such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989 (CRC) and its Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children; the ILO Convention 182 of 1999; and the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime (United Nations, 2016; USDoS, 2021). The UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress, and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially trafficking in women and children was adopted by the UN General Assembly in November 2000 (USDoS, 2021). These were soon followed by the International Labour Organization Convention Concerning the Prohibition and Immediate Action for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labor; and the Protocol to the Convention of the Right of the Child on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography (Gozdziak and Collett, 2005; Sawadogo, 2012). The UN Protocol on trafficking is the most comprehensive instrument globally recognized for addressing human trafficking.

Deane (2017) however, observes that the UN Protocol cannot be applied in isolation of the Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime as they are both complementary in addressing human trafficking issues and transnational criminal syndicates responsible for transnational trafficking in persons globally. According to Clark (2003), the UN Protocol on trafficking is comprehensive in its explanation of trafficking as it addresses three major questions, viz., (a) "what are the acts of trafficking?" which covers issues like the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, and receipt process of trafficking; (b) "what are the means of trafficking?" which addresses methods of adopting victims, such as by threat, use of force, other forms of coercion, abduction, fraud, deception, abuse of power, abuse of a position of vulnerability, and receiving or paying of benefits; and (c) "what are the purposes of trafficking?" which addresses the rationale behind trafficking, such as for exploitation, prostitution of others, other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labor or services, slavery or practices like slavery, servitude, and the removal of organs (Clark, 2003).

In Africa, there is no specific protocol that directly addresses human trafficking; hence, there is heavy reliance on protocols that deal with fundamental human rights (Mensah-Ankrah and Sarpong, 2017; Aniche and Moyo, 2019). The African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights of 1981 is the document that specifies some basic rights which are in many ways useful within the context of human trafficking (Mensah-Ankrah and Sarpong, 2017). For instance, articles 4, 5 and 18(13) of the African Charter on Human Rights, all point to the right of the individual to personal liberty, dignity, and the abolishment of all forms of exploitation such as torture, slavery, inhumane treatment, and punishment and above all, the elimination of discrimination against women and the protection of their rights and those of children (Mensah-Ankrah and Sarpong, 2017; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). Similarly, the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (Charter RWC) of 1990 also addresses issues of rights but does not properly define or give meaning to child trafficking (Donati, 2010; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). Lastly, the Maputo Protocol, known as Protocol to the Africa Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, was adopted in 2003 to consolidate the provisions of the African Charter (Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). Like the other Charters, the Maputo Protocol similarly only provides for the rights of women, as only Article 18(3) provides for the protection of the rights of women and children (Aniche and Moyo, 2019).

In West Africa, there are numerous national policies in place that define human trafficking. These include: the Transportation of Minors and the Suppression of Child Trafficking Act 4 of 2006 in Benin, which criminalizes all forms of child trafficking; the 2005 Law Related to Child Smuggling (supplemented by the Child Code of 2007) in Togo; the 2014 law that criminalizes the sales of children, child prostitution, and child pornography in Burkina Faso; the 2010 Law No 2010-272 Pertaining to the Prohibition of Child Trafficking and the Worst Forms of Child Labor in Cote d'Ivoire, which is the first to stipulate punishment for trafficking offenses; and the Trafficking in Persons Law Enforcement and Administration Act 2003 in Nigeria (Deane, 2017). Notably, of all the protocols in the West African sub-region, only Nigeria addresses and condemns all forms of trafficking while the other countries do not fully address this (Deane, 2017). The subsequent sections discuss how these policies have been implemented and deployed in addressing the menace of trafficking in West Africa.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with the phenomenon and trends of human trafficking, as well as the conventions emplaced that (in)directly attempt to address this violation of human rights, this section presents a critical discussion of the efforts by ECOWAS and the West African states. International law generally provides that states have the onus to prevent and fight against human trafficking (Obokata, 2019), as evident in Article 35 of the 1989 UN CRC, which urges state parties to "take all appropriate national, bilateral and multilateral measures to prevent the abduction, the sale, or traffic in children for any purpose or in any form" (UNICEF, 2002). At the international level therefore, the UNODC has been and continues to promote initiatives that aim at assisting West African states to confront human trafficking at regional and national levels. Among its many initiatives, was the Vienna 2017 training workshop which aimed at fostering regional cooperation among West African states that are also members of the West African Network of Central Authorities and Prosecutors (WACAP) against Organized Crime, to build capacity and work toward combating human trafficking, exploitation, and migrant smuggling within and across West African states (UNODC 2017).

Considering the depth of trafficking in persons across West African and African territories with international criminal syndicates (UNODC, 2020; US Department of State, 2018), tackling this menace effectively must necessarily involve collaborative efforts between local and international agencies and institutions of government and law enforcement. To this end, Sawadogo (2012) appraises that not only have non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and inter-governmental organizations been pivotal in helping West African states address human trafficking, but their interventions have contributed significantly to the enactment of national action plans as well as the establishment of a regional security structure. In exploring the efforts and responses engaged so far, note is taken that ECOWAS' 2002 to 2003 Initial Plan of Action against Trafficking in Persons was anchored on criminal justice response strategies with calls on states in the region to implement the criminalization of human trafficking offenses into law (ECOWAS, 2001). In line with this plan, states at their national levels were obliged to enact laws that aim to protect trafficked victims and establish regulatory frameworks that accord victims opportunity for recompense (ECOWAS, 2001).

Undergirding this plan was also the goal to raise awareness, gather, and cooperatively share national information on the processes and methods employed by traffickers, especially traffickers of women and children, as well as on the circumstances, nature, and financial dealings involved in the perpetuation of the trafficking crimes (Andrew and Lawrance, 2012). Reinforcing ECOWAS' legal response and focus against the trafficking of persons, is the WACAP initiative which promotes and facilitates mutual legal and judicial cooperation in combating organized crimes like human trafficking in the different ECOWAS member states (WACAP, 2013). Putting the anti-trafficking laws and policies to action, joint Interpol operations in the West African countries of Senegal, Mali, Niger, Chad, and Mauritania in 2017 resulted in the rescue of almost 500 people, of whom 236 were children (Reuters, 2017). This intervention also led to the apprehension of 40 traffickers accused of child abuse and victimization, forced labor, and violation of human rights (Reuters, 2017). While these strides are being made, bringing the perpetrators to full justice remains a challenge that cuts across all West African countries where the odious crimes of human trafficking are committed.

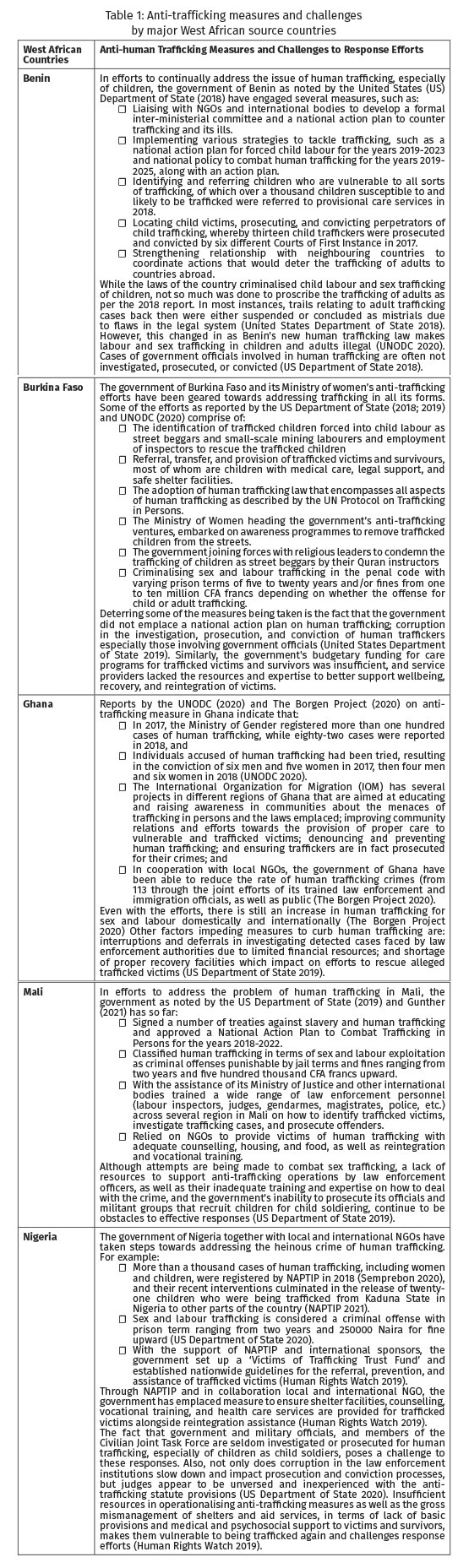

While most African countries now have proper laws in place, some do not enforce them, reporting no investigations or prosecutions. Considering the anti-human trafficking measures at the individual country levels, the table below summarizes a few responses undertaken by governments and organizations of some six randomly selected West African States where the human trafficking rates are noticeable. Furthermore, Table 1 specifies some of the factors impeding the anti-trafficking responses being engaged by these bodies.

Findings from recent data and reports on the trends of the phenomenon of human trafficking and child labor, tend towards the fact that the efforts by the various West African nations and ECOWAS have not fully yielded the desired results (EASO, 2021; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021; UNODC, 2021; USDoS, 2021). For instance, despite establishing legislation against trafficking in persons since 2003, Nigeria still ranks very low in countries with modern slavery index in the world (Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). Furthermore, recent reports and media coverage of the plights of young Nigerians stranded and subjected to torture in transit countries and destination countries in Europe have increased (EASO, 2021), thus questioning the ability and efficiency of NAPTIP in handling and eliminating these trafficking cases in the country. Aside from Nigeria, reports by the UNODC have also identified Ghana, Mali, and other West African countries as major trafficking in person sources and transiting countries (ILO, 2017; IOM, 2017; Mensah-Ankrah and Sarpong, 2017; UNODC, 2021), regional initiatives notwithstanding. While the adoption of various national strategies for addressing the menace is commendable, active results and roles of the ECOWAS in harnessing the national resources at its disposal to help reduce the very high numbers of trafficking in the sub-region, are still very much lacking.

Furthermore, the number of rescued victims of trafficking recorded by the WACAP in comparison with the number of trafficked victims, both within and beyond the sub-region, does not reflect efficiency or success in the endeavors. For instance, joint operations by the nations of Mali, Niger, Senegal, Chad, and Mauritania in 2017 were reported to have rescued a total of 500 victims of human trafficking while an annual report on the number of trafficked persons from the sub-region within the same year amounted to more than 4,799 victims (UNODC, 2021). These statistics do not reflect efficiency in tackling or discouraging human trafficking in the region. While national and regional efforts are necessary for tackling the menace of human trafficking in the region, the synergy and utility of the cooperation provided by the WACAP cannot be said to have been utilized to its full potential, as child labor and other forms of exploitation are still recorded in the sub-region. Sadly still, the West African region not only hosts the highest number of child laborers in sub-Saharan Africa but the region also records the highest number of trafficking in persons, illegal migrants, and modern slavery, with children, boys, girls, and women accounting for the majority of the victims in these various categories of menaces (ILO, 2012b, 2017; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021; UNODC, 2021).

While it could be argued that certain domestic and regional factors have worked against the successful implementation of the African Charter on Child and Women's Rights in the region, partnerships with the international community and organizations such as the European Union (EU) would have at least set the region on the path of success in the area of eradicating child labor. At the present however, issues of law enforcement corruption, border porosity, and the lack of tools and equipment to enforce and prosecute the various legislations on human trafficking are still grappled with across the sub-region (Aniche and Moyo, 2019; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). Furthermore, the regional body and framework for enforcing the measures designed for the elimination of human trafficking and enhancing child rights in the region, WACAP, is still largely ill-equipped and unable to keep up with the growing cases of trafficking in persons in the region, especially the victims of sexual exploitation. As Obokata (2019) asserts, the regional and national governments in the West African region seem to be more concerned with initiating legal frameworks than implementing and enforcing these frameworks. This is because, as Aniche and Moyo (2019) recognize, while acts and legislations exist, the institutional capacity for enforcing these legislations is lacking in countries in the region.

While it is recognized that the fight against human trafficking takes on many forms, the national and regional strategies tend to be more focused on legal proceedings against perpetrators than actually preventing the menace (Sawadogo, 2012). According to Britton and Dean (2014), international responses and efforts tend toward prioritizing preventive measures and support for trafficked victims and survivors rather than reactive measures. There is no doubt that West African states are sincere in their efforts to address and combat the menace of trafficking in persons especially with the bad press that accompanies it, and this dedication is evident in the national strategies and signatories to national and international human rights and anti-trafficking conventions (Mensah-Ankrah and Sarpong, 2017; Aniche and Moyo, 2019; Mlambo and Ndebele, 2021). An assessment of the strategies and efforts of the regional and national strategies however, reveals operational and strategic loopholes. These responses are majorly reactive and not preventive. Reactive strategies primarily respond to the activity after trafficking of victims have been done and this is evident in the fact that victims are either discovered in their destination countries and measures are put in place to return them to their homes or are stranded on the journeys after being discovered by international interventions (Sawadogo, 2012; Shelly, 2014; Deane, 2017). The problem with this strategy, however, is that victims may already have been subjected to the different trafficking hazards before they are rescued (ILO, 2012a, 2012b, 2017; IOM, 2017; UNODC, 2021). On the other hand, preventive measures -which are currently not adequately engaged by the WACAP and nations in the West African sub-region - make trafficking impossible and preventable. These include addressing socio-economic and socio-political issues of West Africans, addressing insecurity, and focusing on rural orientation strategies aimed at enlightening people on the phenomenon and dangers of human trafficking. Current evidence, however, suggests that these preventive strategies are hardly engaged across communities and towns in the sub-region, as is evident in the continual gullibility of rural parents and young persons (UNODC, 2021; USDoS, 2021).

It is important therefore, for states within the West African sub-region to not only focus on the various national strategies that react to human trafficking but ensure the implementation of legislations and strategies that protect the rights of women and children -- particularly girls - in the sub-continent (ECOWAS, 2008; Aniche and Moyo, 2019). Until these fundamental structures are inculcated in the cultural and traditional practices of West Africans and Africans at large, the approaches to combating the menace of human trafficking in the region would be merely reactive with little success. Building institutional capacities for addressing these issues is also central to the strategic preventive measures that will put the subregion in the position to adequately address the human trafficking and child labor issues bedeviling it.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Trafficking in persons disrespects human rights and constitutes a crime against humanity. In West Africa, the use ofmultiple routes for human trafficking, compounded by the involvement of government officials in the different trafficking networks, exacerbates the crime, especially as society looks to them for solutions. In addressing the crisis of human trafficking, therefore, most West African countries have enacted anti-trafficking national action plans and policies, thus raising awareness on how to fight the crime and its impact on society. Additionally, anti-trafficking legislations in some of the West African states encompass all forms of trafficking identified in the UN Trafficking in Persons Protocol. However, effective implementation remains an issue which is further worsened by the corruption that clouds investigations and prosecutions, as well as the previously described challenges. Likewise, the national plans as well as other strategies adopted by governments and organizations, have, in most instances, also fallen short of addressing the different dimensions of human trafficking. Noticeably, these challenges persist despite demands for domestic legislation in compliance with the UNCRC and the ILO Convention (No. 182) and Recommendation (No. 190) on 'the Worst Forms of Child Labor' to ensure adequate prosecution, trial, and punishment of traffickers (Andrew and Lawrance 2012). This study stresses that long-term solutions to human trafficking are an imperative, hence the recommendations below. To this end, this study recommends that:

a) The effective domestication of international treaties as well as coordination in the implementation of national policies, would, among other measures, address the underlying problem of human trafficking in West Africa. Enacting domestic legislation to prioritize and lend support to the rights of citizens not to be trafficked, the government's duty to uphold the law, and protect its citizens from all forms of harm and violation of their human rights, will be needed to localize international laws. Since these are realized through the creation of national plans, promoting consensus for their effective implementation demands that all relevant stakeholders be consulted to enable them to recognize the value of the policies and their operational frameworks. Coordination in the enforcement of these laws and policies will also imply delegating various duties to relevant law enforcement divisions or units, supplemented by adequate training in anti-trafficking operative measures. Doing this will provide and enable governments to build capacity and respond to trafficking cases more effectively.

b) Governments in collaboration with NGOs need to develop and implement robust and supportive outreach, early warning, and awareness programs for communities that are susceptible to and at risk of human trafficking. Having such community projects may propel communities to create support networks that look out for everyone in the community, as well as provide the platform for empowerment, involvement, and confidence-building to report suspicious activities of human trafficking.

c) Coordinated and joint efforts by border guards of member states at reinforcing border security and control will also make a difference in monitoring, preventing, and limiting the movement of people across the borders.

d) Government should also perform its basic duties in the border communities by providing basic amenities needed for daily survival, which many of the communities lack.

e) Government and various stakeholders like the NGOs should synergize with the traditional institutions in those communities. This would go a long way in knowing the plight of the people, and also help to expose and identify various trafficking syndicates that infiltrate those communities to source for children and use those routes for their nefarious activities.

REFERENCES

Ali, A.M. 2005. Treading along a treacherous trail: Research on trafficking in persons in South Asia. International Migration, 43(1-2): 141-164. [ Links ]

Anarfi, J.K. 1998. Ghanaian women and prostitution in Côte d'Ivoire., in Kempadoo, K. and Doezema, J. (Eds.), Global sex workers: Rights, resistance and redefinition. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Andrew, R. and Lawrance, B.N. 2012. Anti-trafficking legislation in sub-Saharan Africa: Analyzing the role of coercion and parental responsibility. Fourth Annual Interdisciplinary Conference on Human Trafficking, University of Nebraska - Lincoln.

Aniche, E.T. and Moyo, I. 2019. The African Union (AU) and migration: Implications for human trafficking in Africa. AfriHeritage Working Paper 2019 006.

Bangladesh Counter Trafficking Thematic Group. 2003. Revisiting the human trafficking paradigm: The Bangladesh experience. Dhaka: IOM-CIDA. [ Links ]

Britton, H.E. and Dean, L.A. 2014. Policy responses to human trafficking in Southern Africa: Domesticating international norms. Human Rights Review. Available at: https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/bitstream/handle/1808/13033/Britton_PolicyResponse s.pdf;jsessionid=438FB1AB14F2E1D592365E6D25A49A84? sequence=1

Clark, M.A. 2003. Trafficking in persons: An issue of human security. Journal of Human Development, 4(2): 247-263. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464988032000087578 [ Links ]

Cullen-DuPont, K. 2009. Human trafficking, Infobase Publishing.

Dajahar, D.L. and Walnshak, D.A. 2018. ECOWAS and human security in West Africa: A review of the literature. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 23(12): 75-83. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-2312027582 [ Links ]

Deane, T. 2017. Searching for best practice: A study on trafficking in persons in West Africa and South Africa. Africa Insight, 47(1): 42-63. https://doi.org/10520/EJC-dd9315dac [ Links ]

De Liévana, G.M.R. and Montánez, P.S. 2015. Paloma Soria trafficking of Nigerian women and girls: Slavery across borders and prejudices. Women's Link Worldwide. Available at: https://www.womenslinkworldwide.org/files/5831abe9adf129d7b16afccbea714dd0.pdf

Doezema, J. 2002. Who gets to choose? Coercion, consent and the UN trafficking protocol. Gender and Development, 10(1). Available at: https://www.statista.com/topics/4238/human-trafficking/knowledgehub/resource_centre/GIFT_Human_Trafficking_An_Overview_2008.pdf. [ Links ]

Donati, S.N. 2010. Study on trafficking in persons in West Africa: An analysis of the legal and political framework for the protection of victims. Available at: https://www.Dakar_Saddikh_Niass_en.pdf

Dottridge, M. 2002. Trafficking in children in West and Central Africa. Gender and Development, 10(1): 38-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070215890 [ Links ]

Europe Asylum Support Office (EASO). 2021. EASO Nigeria: Trafficking in human beings. Country of Origin Information Report, April 2021. https://doi.org/10.2847/777951

Farrell, A. and De Vries, I. 2020. Measuring the nature and prevalence of human trafficking. In Winterdyk, J. and Jones, J. (Eds.), The Palgrave international handbook of human trafficking. Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 147-162.

Fitzgibbon, K. 2003. Modern-day slavery? The scope of trafficking in persons in Africa. African Security Studies, 12(1): 81-89. https://doi.org/10.1080/10246029.2003.9627573 [ Links ]

Gould, C. 2011. Trafficking? Exploring the relevance of the notion of human trafficking to describe the lived experience of sex workers in Cape Town, South Africa. Crime, Law and Social Change, 56(5): 529-546. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10611-011-9332-3 [ Links ]

Gozdziak, E.M. and Collett, E.A. 2005. Not much to write home about: Research on human trafficking in North America. International Migration, 43(1/2). [ Links ]

Gunther, M. 2021. Addressing human trafficking in Mali. 22 March. Available at: https://spheresofinfluence.ca/addressing-human-trafficking-in-mali/

Human Rights Watch (HRW). 2019. "You pray for death" - Trafficking of women and girls in Nigeria. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/08/27/you-pray-death/trafficking-women-and-girls-nigeria

Hynes, P., Burland, P., Dew, J., Thi Tran, H., Priest, P., Thurnham, A., Brodie, I., Spring, D. and Murray, F. 2018. Vulnerability to human trafficking: A study of Viet Nam, Albania, Nigeria and the UK. Report of shared learning event held in Hanoi, Viet Nam: 6-7 December 2017. University of Bedfordshire, IOM, IASR.

Ikeora, M. 2016. The role of African traditional religion and 'juju' in human trafficking: Implications for anti-trafficking. Journal of International Women's Studies, 17(1): 4. [ Links ]

Ikome, F.N. 2012. Africa's international borders as potential sources of conflict and future threats to peace and security. Institute for Security Studies Paper 233, May. ISS.

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2012a. Building the capacity of relevant ECOWAS units for the elimination of child labor in West Africa. International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labor (IPEC), Vol 1. Geneva: ILO.

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2012b. Global estimate of forced labor - Executive Summary. Available at: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_norm/@declaration/documents/publication/wcms_181953.pdf

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2017. Global estimate of modern slavery: Forced labor and forced marriage. Walk Free Foundation and International Organization for Migration. Geneva: ILO. [ Links ]

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2017. Global trafficking trends in focus: IOM victims of trafficking data, 2006-2016. Geneva: IOM. [ Links ]

Kreston, S.S. 2014. Human trafficking legislation in South Africa: Consent, coercion and consequences. South African Journal of Criminal Justice, 27(1): 20-36. https://doi.org/10520/ETC158115 [ Links ]

Laczko, F. and Gramegna, M.A. 2003. Developing better indicators of human trafficking. Brown Journal of World Affairs, 10(1): 179-194. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/24590602.pdf [ Links ]

Mensah-Ankrah, C. and Sarpong, R.O. 2017. The modern trend of human trafficking in Africa and the role of the African Union. Working Paper, EBAN Centre for Human Trafficking Studies.

Mlambo, V.H. and Ndebele, N.C. 2021. Trends, manifestations and challenges of human trafficking in Africa. African Renaissance,18(2): 9-34. https://doi.org/10.31920/2516-5305/2021/18n2a1 [ Links ]

National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP). 2021. Child trafficking: 21 children rescued, suspect arrested. Available at: https://www.naptip.gov.ng/21-children-rescued-suspect-arrested/

Obokata, T. 2019. Human trafficking in Africa: Opportunities and challenges for the African Court of Tustice and human rights. In Charles, C., Talloh, K., Clarke, M. and Nmehielle V.O. (Eds.), The African Court of Justice and human and peoples' rights in context: Development and challenges. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 529-552. [ Links ]

Okenyodo, K. 2020. Dynamics of human trafficking in Africa: A comparative perspective. Paper presented at the Countering Transnational and Organized Crime Seminar, Niamey, Niger, 13-17 January.

Okunade, S.K. 2021. Irregular emigration of Nigeria youths: An exploration of core drivers from the perspective and experiences of returnee migrants. In Moyo, J. et al. (Eds.), Intra-Africa migrations: Borders as challenges and opportunities. London: Routledge (Taylor & Francis Group). [ Links ]

Okunade, S.K and Oni, E.O. 2021. Nigeria and the challenge of managing border porosity. Journal of Black Culture and International Understanding, Volume 7. [ Links ]

Onogwu, D.J. 2018. Corruption and efficiency of the customs clearance process in selected countries. Review of Public Administration and Management, 6: 257. https://doi.org/10.4172/2315-7844.1000257 [ Links ]

Reuters. 2017. Forty human traffickers arrested; 500 people rescued in West Africa. November 23. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-libya-migrants-interpol/forty-human-traffickers-arrested-500-people-rescued-in-west-africa-idUSKBN1DN1RL

Sawadogo, W.R. 2012. The challenges of transnational human trafficking in West Africa. African Studies Quarterly, 13(1/2): 95. http://www.africa.ufl.edu/asq/v13/v13i1-2a5.pdf [ Links ]

Shelley, L. 2010. Human trafficking: A global perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Shelly, L., 2014. Human smuggling and trafficking into Europe: A comparative perspective. Available at: www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/.../BadActors-ShelleyFINALWEB.pdf

Sita, N.M. 2003. Trafficking in women and children: Situation and some trends in African Countries. United Nations African Institute for the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders (UNAFRI).

Statista. 2021. Human trafficking - Statistics & Facts. Available at: https://www.statista.com/topics/4238/human-trafficking/#dossierKeyfigures

Taylor, E. 2002. Trafficking in women and girls. Paper prepared for Expert Group Meeting on Trafficking in Women and Girls, Glen Cove, New York, 18-22 November.

Thompson, B.R. 2003. People trafficking: A national security risk in Mexico. Mexidata. Available at: www.mexidata.info/id93.html

United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). 2002. Child trafficking in West Africa: Policy responses. UNICEF Innocenti Insight, Florence, Italy. Available at: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/insight7.pdf

United Nations International Crime Research Unit (UNICRU). 2004. Program of Action against trafficking in minors and young women from Nigeria into Italy for the purpose of sexual exploitation. Final Report, October-April, United Nations.

United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICJRI). 2003. Trafficking of Nigerian girls to Italy. Report of field survey in Edo State. Available at: http://www.unicri.it/topics/trafficking_exploitation/archive/women/nigeria_1/research/rr_okojie_eng.pdf

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). 2017. West Africa: UNODC promotes regional cooperation in human trafficking and migrant smuggling cases. Available at: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/glo-act/west-africa_-unodc-promotes-regional-cooperation-in-humantrafficking-and-migrant-smuggling-cases.html

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). 2020. Global report on trafficking in persons: Country profile - Sub-Saharan Africa. Available at: https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/tip/2021/GLOTIP_2020_CP_Sub-Saharan_Africa.pdf

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). 2021. Global report on trafficking in persons 2020. Vienna: UNODC. [ Links ]

United States Department of State (USDoS). 2013. Human trafficking and smuggling. Available at: http://m.state.gov/md90434.htm

United States Department of State (USDoS). 2021. Trafficking in Persons Report, June. Washington DC: USDoS. [ Links ]

West African Network of Central Authorities and Prosecutors (WACAP). 2013. West African Network of Central Authorities and Prosecutors against Organized Crime. Available at: https://www.wacapnet.com/

Wheaton, E.M., Schauer, E.J. and Galli, T.V. 2010. Economics of human trafficking. International Migration, 48(4): 114-141. https://doi.org/10.1111/U468-2435.2009.00592.x [ Links ]