Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.40 n.1 Pretoria Feb. 2020

https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40n1a1458

ARTICLES

School climate, an enabling factor in an effective peer education environment: Lessons from schools in South Africa

Benita MoolmanI; Roshin EssopII; Mokhantso MakoaeII; Sharlene SwartzIII; Jean-Paul SolomonIV

IGlobal Citizenship Programme, Centre for Higher Education Development, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa benita.moolman@uct.ac.za

IIHuman and Social Development Unit, Human Sciences Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa

IIIEducation and Skills Development Unit, Human Sciences Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa and Philosophy Department, University of Fort Hare, Alice, South Africa

IVSchool of Social Sciences, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Globally, peer education and school climate are important topics for educators. Peer education has been shown to improve young people's decision-making and knowledge about healthy and prosocial behaviour, while a positive school climate contributes to positive learning outcomes in general. In this article we explore the role of school climate in enabling the success of peer education outcomes. We do so by considering 8 geographically and socially distinct schools in the Western Cape province of South Africa where the peer education programme, Listen Up, was implemented, and for which measures of peer education quality exist. We then report a qualitative assessment of each school's climate characteristics (student-interpersonal relations, student-teacher relations, order and discipline, school leadership, and achievement motivation), conducted through a rapid ethnography drawing on work by Bronfenbrenner (1977) and Haynes, Emmons and Ben-Avie (1997). Finally, we conclude that school climate can enhance learning and positive peer education outcomes.

Keywords: learning environments; peer education; rapid ethnography; school climate; Western Cape

Introduction

Globally, schools are becoming the sites of choice for peer education concerning youth health issues. This is because youth health issues, including sexual health and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, substance abuse, and mental health problems, are issues that schools increasingly need to confront. Consequently, while peer education has demonstrated various positive outcomes on those who participate, it remains a subject of scrutiny and evaluation (Campbell & MacPhail, 2002; Flisher, Mathews, Guttmacher, Abdullah & Myers, 2005). Because schools are complex contexts in which young people learn, develop, and encounter "rules, regularities, and forms of authority" that mirror society at large (Wacquant, 2008:268), it seems important that such socio-cultural environments also become sites of evaluation. Frequently there is a disjuncture between what learnersi learn at school and the attitudes or dispositions of their families and others in the non-school environments in which they spend time. This is particularly true in the South African context, which is still affected by continuities from the apartheid era (Bray, Gooskens, Kahn, Moses & Seekings, 2010; Reay, Crozier & Clayton, 2009), but also globally (Wacquant, 2008).

In addition, researchers have been concerned that the effectiveness of peer education for health promotion in South African schools is likely to be influenced by both the socio-cultural context and climate present in a school (Flisher et al., 2005). The climate in South African schools has recently received attention in relation to violence in schools (Barnes, Brynard & De Wet, 2012), health (Pretorius & De Villiers, 2009), and academic achievement, with a particular concern being completion rates (Milner & Khoza, 2008). However, to date there has been little focus on the prevalence of various aspects of school climate prior to peer education programmes being delivered. In this paper we ask: Can school climate create an enabling environment (an environment that enables peer education to work for goals such as those related to individual health and well-being) for peer education and what are the underlying factors? In order to address this question, we review peer education in schools as sites of social intervention. We also provide an overview of our conceptual framework drawing on Bronfenbrenner's (1977) ecological framework to account for the various contexts that shape human development, as well as the concept of school climate as outlined by Haynes et al. (1997). This is followed by a description of the research design, namely a rapid ethnography (Millen, 2000), used for data collection. We then proceeded with a thematic analysis before discussing our findings as these relate to several elements of school climate identified by Haynes and colleagues.

The Peer Education, Evaluation Study

Peer education is described as the teaching and sharing of information among people of the same age and status (Sciacca, 1987, cited in Milburn, 1995:407). Such education programmes target the peer group as the unit of transformation to alter social norms with the aim of using these group members as agents of change (Chandan, Cambanis, Bhana, Boyce, Makoae, Mukoma & Phakati, 2008). Peer education has increasingly become an intervention of choice for organisations and schools that focus on youth. As children and youth are more likely to obtain health-related (i.e. HIV) information from educational institutions, schools are an important point of contact (Brookes, Shisana & Richter, 2004; Shisana & Simbayi, 2002) for reducing risky and harmful sexual behaviour in children and the youth. This article is based on a peer education evaluation study. In the evaluation we used a mixed method research design to assess the impact of a structured, time-limited, curriculum-based peer-led educational programme, Listen Up, (that deals with, among others, support, decision‑making, relationships, HIV risk, alcohol, pregnancy) involving Grade 8 learners and peer educators in Western Cape schools.

Based on information provided by the department of education, the programme targeted Grade 8 learners who were exposed to high-risk behaviour in schools in a number of districts in the Western Cape. The learners' progress was monitored over the course of two years. Changes in their knowledge, attitudes, and intentions were measured at three intervals during 2012 and 2013 (immediately before the intervention, immediately after the intervention, and five to seven months later) and compared with a control group (measured at two intervals) who did not participate in the peer education programme. To ensure a balance of districts and implementing partners, eight schools running peer education programmes were selected for the qualitative study in consultation with education department officials. These schools served as sites for in-depth case studies of how the programme was implemented, and the contexts in which peer education took place. Firstly, we discuss the seven school climate indicators identified as useful for enabling a positive environment for facilitating effective peer education outcomes. Then we discuss the synergy between school climate and peer education outcomes.

Defining School Climate

The notion "school climate" has been characterised in various ways (Anderson, 1982; Bosworth, Ford & Hernandaz, 2011; Zullig, Koopman, Patton & Ubbes, 2010). In general, school climate is defined as the conditions present in a learning environment (Shiner, 1999); these conditions create experiences that tend to shape learning and development (MacNeil, Prater & Busch, 2009). For this study, elements identified by Haynes et al. (1997) were particularly useful. Whereas some notions of school climate have focused primarily on the school itself, Haynes et al. (1997) recognise that the community and its relationship with the school are critical factors in the formation of the school climate. In addition to some expected components, such as student interpersonal relations, student-teacher relations and order and discipline, they also acknowledge the importance of parent involvement, school-community relations, achievement motivation, staff dedication to student learning, and leadership. The quality of these elements, coupled with the effective delivery of health-related information, highlight the vital role that school climate can play in the peer education process. The elements identified by Haynes et al. (1997) dovetail with Bronfenbrenner's (1977, 1986) ecological framework for human development, which takes socio-cultural and historico-political context seriously. We depict this relationship between Bronfenbrenner's (1977, 1986) contextual imperative with Haynes et al.'s (1997) elements of school climate in Figure 1 in which the critical link between school climate and various aspects of students' lives in context is illustrated.

Haynes et al. (1997) discuss 14 characteristics that they associate with positive school climate. While the scope of this paper does not permit a detailed discussion of each characteristic, seven emerged as important. They are student interpersonal relations, student-teacher relations, school leadership, order and discipline, school-community relations, achievement motivation, and school buildings.

Method

The overall study was focused on evaluating the impact of a peer education programme related to sexual health risk reduction implemented in 35 Western Cape schools. It comprised a quantitative longitudinal experimental research design implemented over twenty-four months. The qualitative component of the study focused on obtaining in-depth information about the impact of the programme in eight schools. The methods used to measure impact included observations at participating schools, semi-structured, in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions with all role players and stakeholders. A rapid but in-depth ethnography conducted over a week through observation and participation in school life was used to study each school context. The Human Sciences Research Council's research ethics committee provided ethical clearance, the Western Cape Education Department and the schools provided permission to conduct the study, and written consent was obtained from participants and parents/guardians of participants under 18 years old. We derived the data for determining impressions of school climate from observation of the eight schools.

Characteristics of Participating Schools

Table 1 summarises the pertinent features of each school.

Tools

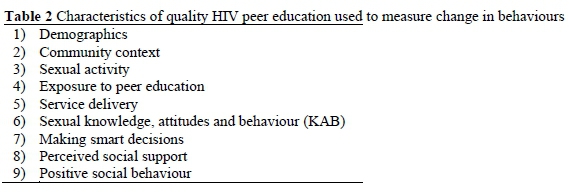

Through a process of literature review and consultation with key stakeholders, the indicators of peer education (presented in Table 2) were taken to be adequate measures of behavioural change that has been shown to reduce adolescents' exposure to HIV infection. We report on three indicators that were positively changed as a result of peer education, under influence of school climate factors, namely, perceived social support, making smart decisions, and positive social behaviour.

Data Collection - Rapid Ethnographies

In this study we used a technique known as rapid ethnography (Millen, 2000). The researchers entered the sites they were going to study with "a specific data plan, identified informants, and specific timelines" (Kluwin, Morris & Clifford, 2004:63). The aim was to use the essential elements of prolonged ethnographic methods while maximising flexibility (Beebe, 2001; Millen, 2000). Following a pre-constructed ethnography, the first stage of data collection consisted of week-long ethnographic observations of the school contexts. Later, observations were made of particular lessons, to focus more directly on classroom dynamics, including teaching methods and general interactions between teachers and learners. Each researcher wrote an ethnographic account of his or her observations of the assigned school, which was used as primary data for analysis.

Analysis

The ethnographic accounts collected by five field researchers were analysed using ATLAS.ti software, first through open coding to find overall themes in the data, then more closely aligned to the rapid ethnography schedule (see Miles & Huberman, 1984), and finally using Haynes et al.'s (1997) elements of school climate. We found that most of the data coincided with seven elements of Haynes et al.'s (1997) rubric. To further summarise the data we rated schools on these seven dimensions of school climate, allocating simple categories of high (positive), low (negative) or neutral ratings, and assigning scores of 1 (high rating), -1 (low rating), and 0 (neutral rating). This resulted in a school climate score from which we categorised the schools according to most positive, less positive and least positive climate. We report on these in the following section.

Findings

The aim of the school observations was to observe for characteristics of school climate in the eight intervention schools. The findings are a reflection of the school climate indicators that appeared most strongly in the data. We did not attempt any correlations of the data but rather provide a descriptive account of the variable of peer education (as defined in the study) in relation to seven indicators of school climate, defined by Haynes et al. (1997). We reflect on student interpersonal relations, student-teacher relations, school leadership, order and discipline, achievement motivation and school buildings.

Student Interpersonal Relations

This element of school climate describes the "level of caring, respect, and trust that exists among students in the school" (Haynes et al., 1997:327). Haynes et al. (1997) argue that supportive peer relationships are important for school attendance. The manner in which students interact with one another contributes to their eagerness and desire to attend school and learn (Haynes et. al., 1997). A positive finding in this study was that consistent violence or significant intra-school conflict was not evident at any of the schools. However, we cannot indicate with certainty that this was as a result of the peer education programme. School G and F had had positive student interaction with good attendance. At School G the learners coexisted happily with some teasing and playfulness. At most of the schools learners would congregate in groups according to gender and age/grade. Although, in some instances, particularly in the classrooms, girls and boys engaged eagerly in conversation. Many learners spent their time out of the classroom in small groups talking to one another, but at some schools, informal games or activities, which were usually segregated by gender, took place. For example, at School G, the girls tended to sit in groups talking, while many of the boys played touch rugby. The fieldworker noted as follows:

Young people seemed to coexist happily at school. Quite a bit of horseplay between girls and boys was occurring with girls hitting boys playfully, and teasing each other. Lots of conversations in classrooms were taking place between young men and women. On the playground however, games and groups were single sex. Boys played touch, girls sat in groups on the grass. (Fieldworker, School G)

Daily attendance is good with approximately 520 (out of 760) children bussed in daily. The rest of the students walk to school (Fieldworker, School F).

In spite of the general sense of camaraderie among the learners, examples of tension, conflict, and bullying were evident in some schools. At School B learners tended to congregate in groups according to race.ii This was evident in the classrooms, during intervals, and after school. However, one learner's experience suggested that the racial and ethnic boundaries were more complex than they first appeared. One of School B's Black African learners spent most of his time with Coloured learners because, as a Sesotho speaker, he felt like an outsider among his isiXhosa-speaking peers. Even though the learners were all treated the same in the classroom, it is possible that several factors could shape learners' experiences of race in the classroom or/and playground, such as the experience of language or residence, as described below:

Though School B is based in a historically Coloured neighbourhood, the student body is predominantly made up of Black African learners who travel to the school from surrounding areas. According to the principal, about 70% of learners are Blacks and 30% Coloured. I did not see any White learners at the school. (Fieldworker, School B)

Segregation by gender and race can at times be by choice. Several factors influence choices made by young learners, for example, language or a sense of familiarity and/or comfort. Segregation by choice was not explored with the learners.

While bullying was primarily verbal at most of the schools, it was physical at School D. Some learners experienced considerable pushing and shoving on the stairs as they moved between classes and they explained that they were constantly afraid of getting hurt in the stairwells.

My informants [girls] also told me about the rotation system that is used at the school. They are unhappy about the system because it is unsafe for them. When I asked why it is unsafe, they told me there is a lot of bullying, pushing and shoving happening on the stairs when they change classes. The boys push them down the stairs and they are always scared when it's time to move to another class. Their preference would be to have the teachers move to their classes (rather than them move from class to class). (Fieldworker, School D)

This quote indicates that student interpersonal relations outside of the classroom remained difficult and even violent. These student experiences demonstrate that mostly the peer education intervention benefitted the peer educators themselves, and not necessarily the whole school. Instances such as these suggested by the informants reveal that peer education did not impact the whole school.

Student-Teacher Relations

Two other important factors in school climate are student-teacher relations or the "level of caring, respect, and trust that exists between students and teachers in the school," as well as the staff's dedication to student learning, which can be seen in the "effort of teachers to get students to learn" (Haynes et al., 1997:327). According to Haynes et al. (1997) teachers' negative comments and unfairness contribute to learners' anxiety, lack of discipline, and dropout rates in school. The data also indicates that generally, a teacher-centred approach to teaching was quite common across the sample, with some teachers taking it to the extreme and not welcoming questions or comments from learners. However, most of the schools displayed an amicable relationship between teachers and learners suggesting that both accepted this approach. At Schools G and F there generally appeared to be supportive relationships between learners and teachers, without any major disciplinary issues arising. Consequently, these schools displayed learners with positive attitudes to learning.

Teachers seemed to be supportive and kind to students, there seemed to be a good atmosphere in the school. Maurice and Michaelaiii who were my informants for the day said that they liked their teachers. Michaela said that one of her teachers put her arm around her and spoke kindly to her when she had a problem. There does seem to be a good rapport between teachers and students. In the lesson observed students responded to teachers, listened and were responsive although some dozed with their heads on their hands. (Fieldworker, School G)

There seems to be good working relationships between students and most of the teachers. In some of the life orientation classes I sat in, the class was working quietly, taking down notes, and helping each other (Fieldworker, School, F).

However, there was a wider range of student-teacher relations within schools than between schools. At School A we were made aware of a teacher who had a reputation for being a remarkable science and maths teacher. However, the learners disliked him and had little respect for him because of his intimidating and, sometimes, insulting behaviour towards them.

There was another teacher the youth did not like, he was a bully and would yell at youth without listening to them. He was derogatory and nasty to the youth. It was surprising that he was allowed to openly bully youth in this way. Later I was told that he was a fantastic science and maths teacher, despite his bullying. It seemed common knowledge amongst youth and teachers that he was a bully. The youth were scared of him but had no respect for him. It was sad to see the way he spoke to them, purposefully putting them down. (Fieldworker, School A)

In contrast, just about all the learners were positive about another teacher who was not only supportive regarding academic matters, but the learners also felt that they could talk to him about any issues of concern.

The favourite teachers, like Mr X, was often mentioned as someone they could go to for advice or help. They explained to me that academic help was always available, but not all the teachers were approachable for other things. Mr X, an openly homosexual man, took an interest in all the youth. His concern for their well-being was evident and the youth felt free to ask questions around poverty, sexuality, gender powers, and parental relationships during his class. Their respect for Mr X was evident in their obedience and attitudes towards him. (Fieldworker, School A)

These findings reflect on the student-teacher relationships as one of the indicators of school climate as defined by Haynes et al. (1997). The peer education programme had indicators such as perceived social support and positive social behaviour, which manifests in student-teacher relationships, hence the above reflection.

School Leadership

This school climate leadership dimension focuses on the "principal's role in guiding the direction of the school and in creating a positive climate" (Haynes et al., 1997:327). Some schools did not display a posi-tive climate or confidence in the principal. At School D some learners were more vocal about their displeasure with the principal and the running of the school, especially regarding the way in which order and discipline were handled.

My informants were very critical of the principal; almost everything they told me was how unhappy they were at the way the school is run. They also told me about the cell phones and that they are prohibited in class or anywhere on the school grounds. The main issue is that the learners are not allowed to have the cell phone ringing in class, and they are not allowed to play music on the cell phone at the school grounds/premises. (Fieldworker, School D)

Conversely, the principals at Schools F and G demonstrated strong leadership in creating a positive climate. This was demonstrated by the fact that in School F the day started with a short staff meeting, and at both schools discipline and organisation were taken seriously. Moreover, the conduct of both principals suggested a belief that their leadership and influence stretched beyond what happened in the classroom. For example, when learners were absent from School F, and if deemed necessary, the principal conducted home visits. The principal at School G had developed a positive relationship with the learners, who regarded him as strict but fair. According to Sergiovanni (1998), principals who strive to be instructional leaders are committed to meeting the needs of their schools by serving stakeholders and pursuing shared beliefs and values. Such administrators advocate excellence in student performance by building relationships with stakeholders and staff in their schools, which help create positive environments where all students learn (Hallinger & Heck, 2010).

(Maurice - the key informant) He said that the headmaster was strict and if you didn't come to school, or came late, you got a 'slip' that went into your folder. If you got more than two or three slips per term, they called your parents. If by the end of the year you had 'too many' slips in your file 'you'd be suspended' or 'you'd get into trouble.' Mr Y, the headmaster, was said to be 'quite strict but fair' and a lot of students said they came to school regularly and did not 'bunk' because they were afraid to get into trouble with him. (Fieldworker, School G)

Whereas the quality of leadership in each school differed, School E had to cope without a principal for a year.

The school was undergoing changes during fieldwork. There was an interim principal and the appointment of the principal kept being delayed. The school was in a state of limbo because there was an interim/acting principal. It took the Western Cape Education Department (WCED) one year to appoint a new principal. This created uncertainty at the school. The school is organised but the uncertainty about the appointment of the principal, made any real planning difficult. (Fieldworker, School E)

Even though there was an interim principal during that time, the uncertainty regarding the appointment of a permanent principal relegated the school to a state of limbo. Peer education indicators such as perceived social support manifest in school leadership and student-teacher relations. These two school climate indicators can enable stronger integration and success of peer education within schools if learners perceive peer education lessons as continuation of the caring attitude they experience in schools.

Order and Discipline

Order and discipline as part of school climate focus on the "appropriateness of student behaviour in the school setting" (Haynes et al., 1997:327). Peer education indicators such as positive social behaviour and self-efficacy are shaped through order, discipline, and school leadership. Generally, all the schools in our study had a system in place to maintain order and discipline. At School G records of who arrived late at school were kept daily and parents were called if learners had been late more than twice in a term. Regarding student-teacher relationships, the approach to discipline differed among teachers. For example, at School G one teacher had a list of rules posted on her classroom wall; she had a gentle, yet unwavering, approach to disruptive students.

During Ms X's class, when learners spoke while she was speaking, she stopped the class, and said 'Askies' ('excuse me' in English) until the learners stopped talking. Her classroom also had a list of rules on the wall (Fieldworker, School G).

Learners' perceptions of leadership are often based on the degree of order and discipline in a school as demonstrated by the quote above. School A appeared to be the strictest regarding order and discipline. Learners' movements were strictly controlled, with roll call conducted at the start of each class and, as in some of the other schools, parents of regular latecomers were invited to the school to discuss the matter. In contrast, poor performing schools D, B and E on both the school climate ranking and the peer education gains, exhibited low monitoring by teachers and more discipline challenges (with the exception of School D). At School B learners could smoke in class and disrespect teachers without consequences. Also evident was a lack of monitoring of learners on the teachers' part. At School E, there were security officers to assist when learners were truant (between periods and classrooms) because teachers could not control the learners' behaviour on the school grounds and in the classrooms. There was also a sense that learners did not want to learn and were wandering the school grounds during classes. The harsh disciplinary measure such as manual work did not seem to encourage learners' positive behaviour.

The extent to which learners are aware of the leeway they have during interval was exemplified by a brief episode on my final day at the school. Over the five days I had spent at School B, I had become mostfamiliar with a group consisting mainly of male Col- oured learners in Grades 8 and 9. On approaching the group, I noticed they were passing around a cigarette. They did not try to conceal it and after I chatted to them for about 5 minutes, one boy passed the cigarette to me, several others urging me to have a 'skyf.' They eventually gave up, after I declined the offer numerous times, amidst general laughter within the group. (Fieldworker, School B)

There is a tension of managing the learners because of discipline issues. The learners are often outside of the classroom during class times, hiding in the lanes in between different buildings (away from the teachers). There is to some degree an 'I-don't-care attitude' by the learners, and a sense of disrespect from learners (the children answer back when teachers speak and discipline the students). The teachers feel undermined by the learners. (Fieldworker, School E)

Order and discipline as school climate indicator can support peer education indicators such as positive social behaviour and perceived social support. When order and discipline is experienced as harsh, or the teachers are held at ransom by learners, it becomes a difficult environment for peer education to flourish. By definition, peer education is not part of the formal curriculum and is delivered by peers who do not have authority over learners, therefore the success of their efforts depends on the school climate.

At School D a few teachers disciplined learners inappropriately for what appeared to be trivial matters. Instances were observed where learners were made to leave the classroom for talking. At schools where order and discipline were maintained, learners scored high on the indicator, positive social behaviour. This showed that learners were more likely to be aware of the consequences of their choices and actions.

The teacher does more talking in the class and the learners answer the questions. In many of the classes with the male teachers I noticed a very effective system in which the teacher would speak and let the learners say the last word. That was effective because I observed, even learners who did not know the answer the first time, would eventually catch up to the rest of the class and verbalise their answers as well. This system proved effective in most of the Grade 8 classes I observed. The most disturbing thing was watching children being thrown out of class for trivial things and told to bring their parents. This was sad to watch because it looked like teacherscame to school with their own underlying frustrations and took them out on learners. The learners seemed respectful of the teachers and even though at times they would not be listening to the teacher in class, they had that adult/child respect towards their teachers. (Fieldworker, School D)

As discussed, order and discipline have an impact on positive social behaviour and perceived social support as peer education indicators. In this reflection, the fieldworker shared her observation of interactive engagement between learners and teachers, which can impact on the experience of positive social behaviour as well as perceived social support.

Achievement Motivation

This dimension focuses on the "extent to which students at the school believe that they can learn and are willing to learn" (Haynes et al., 1997:326). This is a slightly broader definition of achievement motivation, which is often more technically defined as quantitative measure of achievement in relation to pass rates. In relation to the peer education indicators, particularly perceived social support, making smarter decisions, and self-efficacy, achievement motivation refers to the manner in which learners demonstrate an eagerness and willingness to learn in the classroom. For example, at School F, although some learners were inattentive (evident from their failing to complete homework), this did not appear to be the norm for the school. In fact, many learners seemed to be engaged with the lessons and participated readily.

During lessons, teachers were helpful, friendly and insistent. Most classrooms in which I observed lessons had posters relating to the subject on the wall. Some had career guidance posters on the walls, and HIV and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) information, and messages. One class displayed students' project on culture and religion. There were posters from Oxford University Press on Mr Z's wall concerning Apartheid history as well as rape and addiction. (Fieldworker, School F)

These intra-school variations were evident at several other schools, including School A. As previously discussed in the section on student-teacher relations, certain teachers were more adept at keeping learners' attention. At School F, the principal and staff made a concerted effort to set the tone for every new school term by encouraging and motivating learners. In such cases where high achievement motivation from teachers formed part of school climate, learners scored better on the indicator, making smarter decisions. This shows that learners were more likely to consider the consequences of their sexual and other health‑related decisions during the peer education programme. Both School H and School A, the latter a former model-C school with a matriculation pass rate above 95%, have considerable dropout rates. While at School H the high rate of dropouts was reported as related to substance abuse, the teachers at School E stated that learners struggled to stay motivated because they did not receive encouragement to focus on their schooling from their families.

They are engaged but they do not stay engaged. They are easily distracted, become restless and then tease each other during class times. I don't think the children are encouraged to learn outside of school and so when they are encouraged to learn at school, it is a hard task to get themto stay interested. My guess would be that they have very little intellectual encouragement at home or in the broader community. (Fieldworker, School E)

In the example above, students find it difficult to concentrate and to remain attentive. There are several contributing factors. School E was situated in a very low socio-economic community, with parents often being seasonal workers, and struggling to provide necessities such as food, water, sanitation, and electricity. Additionally, alcohol abuse and domestic violence were high in this community. We reflect that the socio-economics of the surrounding community influence parental monitoring and learning motivation of the learners at this school.

School Buildings

The schools differed in terms of resources and infrastructure. School A was the best resourced and most organised school in the sample. The buildings, although quite old, were well-maintained with almost no graffiti, other than in the learners' bathrooms. The school also boasted well-kept sports fields, a library, computer rooms, a kitchen, basketball courts, and a braai area for social functions. Additionally, the school had a learner- teacher ratio of 20:1, thanks to several staff members who were appointed by the school governing body in addition to government-supported positions. An on-site psychologist was also employed to assist learners experiencing psychosocial difficulties. Conversely, School D was a mix of organised and disorganised elements. While the library was well-managed, the lack of orderliness during lessons suggested that a different operational management of libraries and other school resources perhaps existed in comparison to the management of school relationships. At times learners were found in classrooms where they did not belong, while teachers selling snacks and sweets disrupted other classes during teaching time.

There is also a lot of buying and selling from the teachers. Which is probably one of the things that surprised me a lot about this school, there are such strict rules on certain things (to be discussed in relevant sections) yet the learners are able to move from class to class, DURING class times and buy snacks and sweets from the teachers who are selling things. This happens even in the middle of a lesson. (Fieldworker, School D)

Discussion

While the schools discussed in this article are situated in a part of South Africa, they represent the diversity of wealth, geographical location and historical provenance of schools in South Africa and globally. What is key in our discussion is the effect of these characteristics on successful implementation of peer education in schools.

The peer education indicators, in particular making smart decisions, perceived social support, and positive social behaviour, have a combined effect with school climate indicators, in particular those focusing on strong relationships, such as student interpersonal relationships and student-teacher relationships. When examining the characteristics of school climate discussed here, the three rural schools, Schools F, G and H, most consistently displayed an enabling and supportive environment. As discussed above, supportive relationships between learners, supportive relationships between students and teachers, and supportive leadership that embraced nurturing disciplining techniques, all contributed to an enabling school climate. These schools made noticeable gains with regard to positive peer education.

The data collected to achieve the aim of the study suggests that when attempting to understand the concept "climate" in a social setting like a school, depending solely on observations of this nature, is not enough. Some of the elements of school climate such as achievement motivation are perceived to depend on individual learners' behaviour, school, home, and community factors. Learners' engagement with sexuality topics suggests their interest in learning life skills, and perhaps more importantly, demonstrate stronger self-efficacy. Unfortunately, it is not always possible to gain access to certain spaces to observe certain types of interpersonal interactions. For example, how principals conduct themselves in disciplinary conversations or observing school-governing-body-parent meetings to obtain insight into less direct didactic learning. Therefore, it might be necessary to combine this rapid ethnography with other forms of data collection, such as semi-structured interviews or a scale constructed specifically to measure school climate and social context. That said, the interviews (and survey items) should not be limited to the school site, but should include the perspectives of local community members, organisations, and other stakeholders. Revising the guide to closely focus on the theoretically-determined aspects of school climate is needed for future studies. We offer a tentative guide, still subject to further field testing, in Table 3.

These questions, while originating from South African case studies, are clearly relevant to other global contexts.

Conclusion

In this article we propose that peer education outcomes improve in school climates that are conducive to learning. Consequently, where school climate is characterised by positive and collaborative interactions and includes positive role models, learners are more likely to generate new perspectives on ways of being and ensuing decisions including those of healthy and pro-social behaviour (Campbell & MacPhail, 2002; Haynes et al., 1997). What is also clear, however, is that school climate is co-created through relationships by learners and teachers and is not determined entirely by structural factors such as families' socio-economic status, a well-resourced geographical location, or favourable historical context. This knowledge, further developed, can contribute to more effective peer education approaches by increasing the readiness of schools to implement this intervention by building on strengths and assets of schools and communities, especially in a global context of limited and dwindling resources.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria - https://doi.org/10.13039/100004417 - as a subcontract through Health and Education Training and Technical Assistance Services. The evaluated peer education programme was implemented by the Western Cape Department of Health and Western Cape Department of Basic Education in collaboration with various non-governmental organisations (NGOs), with technical assistance and monitoring provided by the Centre for the Support of Peer Education.

Authors' Contributions

Benita Moolman was the project manager on the project, coordinated the writing of the manuscript and contributed to the conceptualisation of the manuscript. Roshin Essop contributed to the conceptualisation of the manuscript. Mokhantso Makaoe contributed to the conceptualisation of the manuscript. Sharlene Swartz was the Principal Investigator on the project and contributed to the initial conceptualisation of the manuscript, which had changed dramatically since its first inception. Jean Paul Solomon, did the initial drafting of the paper.

Notes

i . The words "learner" and "student" are used interchangeably to accommodate for the use of the word "student" in the literature but the use of the term "learner" in the study.

ii . Race is used as a social construct and to delineate apartheid racial classifications in the South African context.

iii . All names of participants are pseudonyms.

iv . Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Anderson CS 1982. The search for school climate: A review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 52(3):368-420. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F00346543052003368 [ Links ]

Barnes K, Brynard S & De Wet C 2012. The influence of school culture and school climate on violence in schools of the Eastern Cape Province. South African Journal of Education, 32(1):69-82. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v32n1a495 [ Links ]

Beebe J 2001. Rapid assessment process: An introduction. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press. [ Links ]

Bosworth K, Ford L & Hernandaz D 2011. School climate factors contributing to student and faculty perceptions of safety in select Arizona schools. Journal of School Health, 81(4):194-201. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00579.x [ Links ]

Bray R, Gooskens I, Kahn L, Moses S & Seekings J 2010. Growing up in the new South Africa: Childhood and adolescence in post-apartheid Cape Town. Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner U 1977. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7):513-531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513 [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner U 1986. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6):723-742. [ Links ]

Brookes H, Shisana O & Richter L 2004. The national household HIV prevalence and risk survey of South African children. Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC. Available at http://www.hsrc.ac.za/uploads/pageContent/1641/TheNationalhouseholdHIVprevalenceandrisksurvey ofSouthAfricanchildren.pdf. Accessed 9 January 2020. [ Links ]

Campbell C & MacPhail C 2002. Peer education, gender and the development of critical consciousness: Participatory HIV prevention by South African youth. Social Science & Medicine, 55(2):331-345. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00289-1 [ Links ]

Chandan U, Cambanis E, Bhana A, Boyce G, Makoae M, Mukoma W & Phakati S 2008. Evaluation of My Future is My Choice (MFMC) peer education life skills programme in Namibia: Identifying strengths, weaknesses and areas of improvement. Windhoek, Namibia: UNICEF. Available at http://repository.hsrc.ac.za/bitstream/handle/20.500.11910/5101/5593_Chandan_ EvaluationofMFMC.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 9 January 2020. [ Links ]

Flisher AJ, Mathews C, Guttmacher S, Abdullah F & Myers JE 2005. Editorial: AIDS prevention through peer education. South African Medical Journal, 95(4):245-248. Available at http://www.samj.org.za/index.php/samj/article/viewFile/1608/970. Accessed 4 January 2020. [ Links ]

Hallinger P & Heck RH 2010. Collaborative leadership and school improvement: Understanding the impact on school capacity and student learning. School Leadership & Management, 30(2):95-110. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632431003663214 [ Links ]

Haynes NM, Emmons C & Ben-Avie M 1997. School climate as a factor in student adjustment and achievement. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 8(3):321-329. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532768xjepc0803_4 [ Links ]

Kluwin TN, Morris CS & Clifford J 2004. A rapid ethnography of itinerant teachers of the deaf. American Annals of the Deaf, 149(1):62-72. [ Links ]

MacNeil AJ, Prater DL & Busch S 2009. The effects of school culture and climate on student achievement. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 12(1):73-84. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603120701576241 [ Links ]

Milburn K 1995. A critical review of peer education with young people with special reference to sexual health. Health Education Research, 10(4):407-420. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/10.4.407 [ Links ]

Miles MB & Huberman AM 1984. Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Millen DR 2000. Rapid ethnography: Time deepening strategies for HCI field research. In D Boyarski & WA Kellogg (eds). Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/347642.347763 [ Links ]

Milner K & Khoza H 2008. A comparison of teacher stress and school climate across schools with different matric success rates. South African Journal of Education, 28(2):155-173. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/38/102. Accessed 2 January 2020. [ Links ]

Pretorius S & De Villiers E 2009. Educators' perceptions of school climate and health in selected primary schools. South African Journal of Education, 29(1):33-52. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/230/141. Accessed 2 January 2020. [ Links ]

Reay D, Crozier G & Clayton J 2009. 'Strangers in paradise'? Working-class students in elite universities. Sociology, 43(6):1103-1121. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0038038509345700 [ Links ]

Sergiovanni TJ 1998. Leadership as pedagogy, capital development and school effectiveness. International Journal of Leadership in Education: Theory and Practice, 1(1):37-46. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360312980010104 [ Links ]

Shiner M 1999. Defining peer education. Journal of Adolescence, 22(4):555-566. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1999.0248 [ Links ]

Shisana O & Simbayi L 2002. Nelson Mandela/HSRC study of HIV/AIDS: South African national HIV prevalence, behavioural risks and mass media: Household survey 2002. Cape Town, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

Wacquant L 2008. Pierre Bourdieu. In R Stones (ed). Key sociological thinkers (2nd ed). Hampshire, England: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Zullig KJ, Koopman TM, Patton JM & Ubbes VA 2010. School climate: Historical review, instrument development, and school assessment. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 28(2):139-152. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0734282909344205 [ Links ]

Received: 15 March 2017

Revised: 17 April 2019

Accepted: 14 July 2019

Published: 29 February 2020